Ukraine

Ukraine (Ukrainian: Україна, romanized: Ukrayina, pronounced [ʊkrɐˈjinɐ] (![]()

Ukraine

| |

|---|---|

Anthem: "Derzhavnyy Hymn Ukrayiny" (English: "State Anthem of Ukraine") | |

.svg.png) .svg.png)

| |

| Capital and largest city | Kiev 49°N 32°E |

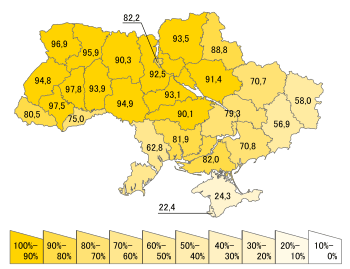

| Official languages | Ukrainian |

| Recognised regional languages | Russian, Rusyn, Belarusian, Yiddish |

| Ethnic groups (2001)[1] |

|

| Religion (2018)[2] |

|

| Demonym(s) | Ukrainian |

| Government | Unitary semi-presidential constitutional republic |

| Volodymyr Zelensky | |

| Denys Shmyhal | |

| Dmytro Razumkov | |

| Legislature | Verkhovna Rada |

| Independence from Russia | |

• Autonomy | 23 June 1917 |

| 22 January 1918 | |

| 1 November 1918 | |

| 22 January 1919 | |

| 24 August 1991 | |

| 28 June 1996 | |

| Area | |

• Total | 603,628 km2 (233,062 sq mi) (45th) |

• Water (%) | 7 |

| Population | |

• April 2020 estimate | (excluding Crimea and Sevastopol) (33rd) |

• 2001 census | 48,457,102[1] |

• Density | 73.8/km2 (191.1/sq mi) (115th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2020 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| GDP (nominal) | 2020 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| Gini (2018) | low · 18th |

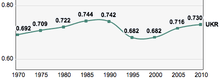

| HDI (2018) | high · 88th |

| Currency | Ukrainian hryvnia (₴) (UAH) |

| Time zone | UTC+2[7] (EET) |

| UTC+03 (EEST) | |

| Driving side | right |

| Calling code | +380 |

| ISO 3166 code | UA |

| Internet TLD | |

The territory of modern Ukraine has been inhabited since 32,000 BC. During the Middle Ages, the area was a key centre of East Slavic culture, with the powerful state of Kievan Rus' forming the basis of Ukrainian identity. Following its fragmentation in the 13th century, the territory was contested, ruled and divided by a variety of powers, including the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, Austria-Hungary, the Ottoman Empire and Russia. A Cossack republic emerged and prospered during the 17th and 18th centuries, but its territory was eventually split between Poland and the Russian Empire. After World War II the Western part of Ukraine merged into the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, and the whole country became a part of the Soviet Union as a single state entity. Ukraine gained its independence in 1991, following the dissolution of the Soviet Union at the end of the Cold War. Before its independence, Ukraine was typically referred to in English as "The Ukraine", but most sources have since moved to drop "the" from the name of Ukraine in all uses.[12]

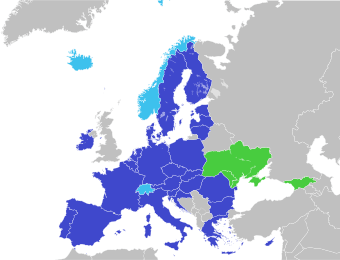

Following its independence, Ukraine declared itself a neutral state;[13] it formed a limited military partnership with Russia and other CIS countries while also establishing a partnership with NATO in 1994. In 2013, after the government of President Viktor Yanukovych had decided to suspend the Ukraine-European Union Association Agreement and seek closer economic ties with Russia, a several-months-long wave of demonstrations and protests known as the Euromaidan began, which later escalated into the 2014 Ukrainian revolution that led to the overthrow of Yanukovych and the establishment of a new government. These events formed the background for the annexation of Crimea by Russia in March 2014, and the War in Donbass in April 2014. On 1 January 2016, Ukraine applied the economic component of the Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Area with the European Union.[14]

Ukraine is a developing country and ranks 88th on the Human Development Index. As of 2020, Ukraine is the poorest country in Europe alongside Moldova in terms of GDP per capita. At US$40, it has the lowest median wealth per adult in the world,[note 1][15] and suffers from a very high poverty rate as well as severe corruption.[16] However, because of its extensive fertile farmlands, Ukraine is one of the world's largest grain exporters.[17][18] It also maintains the third-largest military in Europe after the French and Russian Armed Forces.[19] Ukraine is a unitary republic under a semi-presidential system with separate powers: legislative, executive and judicial branches. The country is a member of the United Nations, the Council of Europe, the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE), the GUAM organization, and one of the founding states of the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS).

Etymology and orthography

There are different hypotheses as to the etymology of the name Ukraine. According to the older widespread hypothesis, it means "borderland",[20] while some more recent linguistic studies claim a different meaning: "homeland" or "region, country".[21]

"The Ukraine" used to be the usual form in English,[22] but since the Declaration of Independence of Ukraine, "the Ukraine" has become less common in the English-speaking world, and style-guides warn against its use in professional writing.[12][23] According to U.S. ambassador William Taylor, "The Ukraine" now implies disregard for the country's sovereignty.[24] The Ukrainian position is that the usage of "'The Ukraine' is incorrect both grammatically and politically."[25]

History

Early history

Neanderthal settlement in Ukraine is seen in the Molodova archaeological sites (43,000–45,000 BC) which include a mammoth bone dwelling.[26][27] The territory is also considered to be the likely location for the human domestication of the horse.[28][29][30][31]

Modern human settlement in Ukraine and its vicinity dates back to 32,000 BC, with evidence of the Gravettian culture in the Crimean Mountains.[32][33] By 4,500 BC, the Neolithic Cucuteni–Trypillia culture flourished in wide areas of modern Ukraine including Trypillia and the entire Dnieper-Dniester region. During the Iron Age, the land was inhabited by Cimmerians, Scythians, and Sarmatians.[34] Between 700 BC and 200 BC it was part of the Scythian Kingdom, or Scythia.[35]

Beginning in the sixth century BC, colonies of Ancient Greece, Ancient Rome, and the Byzantine Empire, such as Tyras, Olbia, and Chersonesus, were founded on the northeastern shore of the Black Sea. These colonies thrived well into the sixth century AD. The Goths stayed in the area, but came under the sway of the Huns from the 370s AD. In the seventh century AD, the territory of eastern Ukraine was the centre of Old Great Bulgaria. At the end of the century, the majority of Bulgar tribes migrated in different directions, and the Khazars took over much of the land.[36]

In the fifth and sixth centuries, the Antes were located in the territory of what is now Ukraine. The Antes were the ancestors of Ukrainians: White Croats, Severians, Polans, Drevlyans, Dulebes, Ulichians, and Tiverians. Migrations from Ukraine throughout the Balkans established many Southern Slavic nations. Northern migrations, reaching almost to the Ilmen lakes, led to the emergence of the Ilmen Slavs, Krivichs, and Radimichs, the groups ancestral to the Russians. After an Avar raid in 602 and the collapse of the Antes Union, most of these peoples survived as separate tribes until the beginning of the second millennium.[37]

Golden Age of Kiev

Kievan Rus' was founded in the territory of the Polans, who lived among the rivers Ros, Rosava, and Dnieper. Russian historian Boris Rybakov came from studying the linguistics of Russian chronicles to the conclusion that the Polans union of clans of the mid-Dnieper region called itself by the name of one of its clans, "Ros", that joined the union and was known at least since the 6th century far beyond the Slavic world.[38] The origin of the Kiev princedom is of a big debate and there exist at least three versions depending on interpretations of the chronicles.[39] In general it is believed that "Kievan Rus' included the central, western and northern part of modern Ukraine, Belarus, and the far eastern strip of Poland. According to the Primary Chronicle the Rus' elite initially consisted of Varangians from Scandinavia.[40]

During the 10th and 11th centuries, it became the largest and most powerful state in Europe.[41] It laid the foundation for the national identity of Ukrainians and Russians.[42] Kiev, the capital of modern Ukraine, became the most important city of the Rus'. In 12th–13th centuries on efforts of Yuri the Long Armed, in area of Zalesye were founded several cities similar in name as in Kievan Rus such as Vladimir on the Klyazma/Vladimir of Zalesye[43] (Volodymyr), Galich of Merya (Halych), Pereslavl of Zalesye (Pereyaslav of Ruthenian), Pereslavl of Erzya.

.jpg)

The Varangians later assimilated into the Slavic population and became part of the first Rus' dynasty, the Rurik Dynasty.[42] Kievan Rus' was composed of several principalities ruled by the interrelated Rurikid knyazes ("princes"), who often fought each other for possession of Kiev.[44]

The Golden Age of Kievan Rus' began with the reign of Vladimir the Great (980–1015), who turned Rus' toward Byzantine Christianity. During the reign of his son, Yaroslav the Wise (1019–1054), Kievan Rus' reached the zenith of its cultural development and military power.[42] The state soon fragmented as the relative importance of regional powers rose again. After a final resurgence under the rule of Vladimir II Monomakh (1113–1125) and his son Mstislav (1125–1132), Kievan Rus' finally disintegrated into separate principalities following Mstislav's death.[45]

The 13th-century Mongol invasion devastated Kievan Rus'. Kiev was totally destroyed in 1240.[46] On today's Ukrainian territory, the principalities of Halych and Volodymyr-Volynskyi arose, and were merged into the state of Galicia-Volhynia.[47]

Danylo Romanovych (Daniel I of Galicia or Danylo Halytskyi) son of Roman Mstyslavych, re-united all of south-western Rus', including Volhynia, Galicia and Rus' ancient capital of Kiev. Danylo was crowned by the papal archbishop in Dorohychyn 1253 as the first King of all Rus'. Under Danylo's reign, the Kingdom of Galicia–Volhynia was one of the most powerful states in east central Europe.[48]

Foreign domination

In the mid-14th century, upon the death of Bolesław Jerzy II of Mazovia, king Casimir III of Poland initiated campaigns (1340–1366) to take Galicia-Volhynia. Meanwhile, the heartland of Rus', including Kiev, became the territory of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, ruled by Gediminas and his successors, after the Battle on the Irpen' River. Following the 1386 Union of Krewo, a dynastic union between Poland and Lithuania, much of what became northern Ukraine was ruled by the increasingly Slavicised local Lithuanian nobles as part of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. By 1392 the so-called Galicia–Volhynia Wars ended. Polish colonisers of depopulated lands in northern and central Ukraine founded or re-founded many towns. In 1430 Podolia was incorporated under the Crown of the Kingdom of Poland as Podolian Voivodeship. In 1441, in the southern Ukraine, especially Crimea and surrounding steppes, Genghisid prince Haci I Giray founded the Crimean Khanate.[49]

In 1569 the Union of Lublin established the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, and much Ukrainian territory was transferred from Lithuania to the Crown of the Kingdom of Poland, becoming Polish territory de jure. Under the demographic, cultural and political pressure of Polonisation, which began in the late 14th century, many landed gentry of Polish Ruthenia (another name for the land of Rus) converted to Catholicism and became indistinguishable from the Polish nobility.[50] Deprived of native protectors among Rus nobility, the commoners (peasants and townspeople) began turning for protection to the emerging Zaporozhian Cossacks, who by the 17th century became devoutly Orthodox. The Cossacks did not shy from taking up arms against those they perceived as enemies, including the Polish state and its local representatives.[51]

Formed from Golden Horde territory conquered after the Mongol invasion the Crimean Khanate was one of the strongest powers in Eastern Europe until the 18th century; in 1571 it even captured and devastated Moscow.[52] The borderlands suffered annual Tatar invasions. From the beginning of the 16th century until the end of the 17th century, Crimean Tatar slave raiding bands[53] exported about two million slaves from Russia and Ukraine.[54] According to Orest Subtelny, "from 1450 to 1586, eighty-six Tatar raids were recorded, and from 1600 to 1647, seventy."[55] In 1688, Tatars captured a record number of 60,000 Ukrainians.[56] The Tatar raids took a heavy toll, discouraging settlement in more southerly regions where the soil was better and the growing season was longer. The last remnant of the Crimean Khanate was finally conquered by the Russian Empire in 1783.[57]

In the mid-17th century, a Cossack military quasi-state, the Zaporozhian Host, was formed by Dnieper Cossacks and by Ruthenian peasants who had fled Polish serfdom.[58] Poland exercised little real control over this population, but found the Cossacks to be a useful opposing force to the Turks and Tatars,[59] and at times the two were allies in military campaigns.[60] However the continued harsh enserfment of peasantry by Polish nobility and especially the suppression of the Orthodox Church alienated the Cossacks.[59]

The Cossacks sought representation in the Polish Sejm, recognition of Orthodox traditions, and the gradual expansion of the Cossack Registry. These were rejected by the Polish nobility, who dominated the Sejm.[61]

Cossack Hetmanate

In 1648, Bohdan Khmelnytsky and Petro Doroshenko led the largest of the Cossack uprisings against the Commonwealth and the Polish king Treaty of Perpetual Peace (1686).[62] After Khmelnytsky made an entry into Kiev in 1648, where he was hailed liberator of the people from Polish captivity, he founded the Cossack Hetmanate, which existed until 1764 (some sources claim until 1782).

Khmelnytsky deserted by his Tatar allies, suffered a crushing deafeat at the Battle of Berestechko in 1651, and turned to the Russian tsar for help. In 1654, Khmelnytsky was subject to the Pereyaslav Council, forming a military and political alliance with Russia that acknowledged loyalty to the Russian tsar.

In 1657–1686 came "The Ruin", a devastating 30-year war amongst Russia, Poland, the Crimean Khanate, the Ottoman Empire, and Cossacks for control of Ukraine, which occurred at about the same time as the Deluge of Poland. The wars escalated in intensity with hundreds of thousands of deaths. Defeat came in 1686 as the "Treaty of Perpetual Peace" between Russia and Poland divided Ukrainian lands between them.

In 1709, Cossack Hetman Ivan Mazepa (1639–1709) defected to Sweden against Russia in the Great Northern War (1700–1721). Eventually Peter recognized that to consolidate and modernize Russia's political and economic power it was necessary to do away with the Cossack Hetmanate and Ukrainian and Cossack aspirations to autonomy. Mazepa died in exile after fleeing from the Battle of Poltava (1709), where the Swedes and their Cossack allies suffered a catastrophic defeat.

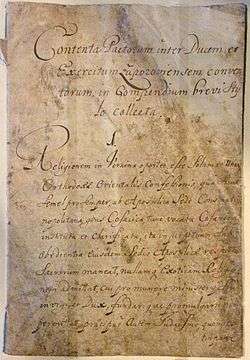

The Constitution of Pylyp Orlyk or Pacts and Constitutions of Rights and Freedoms of the Zaporizhian Host was a 1710 constitutional document written by Hetman Pylyp Orlyk, a Cossack of Ukraine, then within the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth.[63] It established a standard for the separation of powers in government between the legislative, executive, and judiciary branches, well before the publication of Montesquieu's The Spirit of the Laws. The Constitution limited the executive authority of the hetman, and established a democratically elected Cossack parliament called the General Council. The Constitution of Pylyp Orlyk was unique for its period, and was one of the first state constitutions in Europe.

The hetmanate was abolished in 1764; the Zaporozhian Sich was abolished in 1775, as Russia centralised control over its lands. As part of the Partitions of Poland in 1772, 1793 and 1795, the Ukrainian lands west of the Dnieper were divided between Russia and Austria. From 1737 to 1834, expansion into the northern Black Sea littoral and the eastern Danube valley was a cornerstone of Russian foreign policy.

Lithuanians and Poles controlled vast estates in Ukraine, and were a law unto themselves. Judicial rulings from Kraków were routinely flouted, while peasants were heavily taxed and practically tied to the land as serfs Occasionally the landowners battled each other using armies of Ukrainian peasants. The Poles and Lithuanians were Roman Catholics and tried with some success to convert the Orthodox lesser nobility. In 1596, they set up the "Greek-Catholic" or Uniate Church; it dominates western Ukraine to this day. Religious differentiation left the Ukrainian Orthodox peasants leaderless, as they were reluctant to follow the Ukrainian nobles.[64]

Cossacks led an uprising, called Koliyivshchyna, starting in the Ukrainian borderlands of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth in 1768. Ethnicity was one root cause of this revolt, which included the Massacre of Uman that killed tens of thousands of Poles and Jews. Religious warfare also broke out among Ukrainian groups. Increasing conflict between Uniate and Orthodox parishes along the newly reinforced Polish-Russian border on the Dnieper in the time of Catherine the Great set the stage for the uprising. As Uniate religious practices had become more Latinized, Orthodoxy in this region drew even closer into dependence on the Russian Orthodox Church. Confessional tensions also reflected opposing Polish and Russian political allegiances.[65]

After the annexation of Crimea by the Russian Empire in 1783, Novorossiya was settled by Ukrainians and Russians.[66] Despite promises in the Treaty of Pereyaslav, the Ukrainian elite and the Cossacks never received the freedoms and the autonomy they were expecting. However, within the Empire, Ukrainians rose to the highest Russian state and church offices.[a] At a later period, tsarists established a policy of Russification, suppressing the use of the Ukrainian language in print and in public.[67]

19th century, World War I and revolution

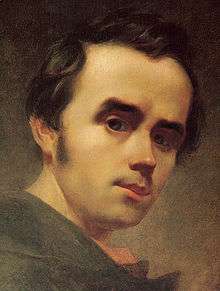

In the 19th century, Ukraine was a rural area largely ignored by Russia and Austria. With growing urbanization and modernization, and a cultural trend toward romantic nationalism, a Ukrainian intelligentsia committed to national rebirth and social justice emerged. The serf-turned-national-poet Taras Shevchenko (1814–1861) and the political theorist Mykhailo Drahomanov (1841–1895) led the growing nationalist movement.[68][69]

After the Russo-Turkish War (1768–1774), Catherine the Great and her immediate successors encouraged German immigration into Ukraine and especially into Crimea, to thin the previously dominant Turk population and encourage agriculture.[70] Numerous Ukrainians, Russians, Germans, Bulgarians, Serbs and Greeks moved into the northern Black Sea steppe formerly known as the "Wild Fields".[71][72]

Beginning in the 19th century, there was migration from Ukraine to distant areas of the Russian Empire. According to the 1897 census, there were 223,000 ethnic Ukrainians in Siberia and 102,000 in Central Asia.[73] An additional 1.6 million emigrated to the east in the ten years after the opening of the Trans-Siberian Railway in 1906.[74] Far Eastern areas with an ethnic Ukrainian population became known as Green Ukraine.[75]

Nationalist and socialist parties developed in the late 19th century. Austrian Galicia, under the relatively lenient rule of the Habsburgs, became the centre of the nationalist movement.[76]

Ukrainians entered World War I on the side of both the Central Powers, under Austria, and the Triple Entente, under Russia. 3.5 million Ukrainians fought with the Imperial Russian Army, while 250,000 fought for the Austro-Hungarian Army.[77] Austro-Hungarian authorities established the Ukrainian Legion to fight against the Russian Empire. This became the Ukrainian Galician Army that fought against the Bolsheviks and Poles in the post-World War I period (1919–23). Those suspected of Russophile sentiments in Austria were treated harshly.[78]

World War I destroyed both empires. The Russian Revolution of 1917 led to the founding of the Soviet Union under the Bolsheviks, and subsequent civil war in Russia. A Ukrainian national movement for self-determination re-emerged, with heavy Communist and Socialist influence. Several Ukrainian states briefly emerged: the internationally recognized Ukrainian People's Republic (UNR, the predecessor of modern Ukraine, was declared on 23 June 1917 proclaimed at first as a part of the Russian Republic; after the Bolshevik Revolution, the Ukrainian People's Republic proclaimed its independence on 25 January 1918), the Hetmanate, the Directorate and the pro-Bolshevik Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic (or Soviet Ukraine) successively established territories in the former Russian Empire; while the West Ukrainian People's Republic and the Hutsul Republic emerged briefly in the Ukrainian lands of former Austro-Hungarian territory.[79]

The short lived Act Zluky (Unification Act) was an agreement signed on 22 January 1919 by the Ukrainian People's Republic and the West Ukrainian People's Republic on the St. Sophia Square in Kiev.[80] This led to civil war, and an anarchist movement called the Black Army (later renamed to The Revolutionary Insurrectionary Army of Ukraine) developed in Southern Ukraine under the command of the anarchist Nestor Makhno during the Russian Civil War.[81] They protected the operation of "free soviets" and libertarian communes in the Free Territory, an attempt to form a stateless anarchist society from 1918 to 1921 during the Ukrainian Revolution, fighting both the tsarist White Army under Denikin and later the Red Army under Trotsky, before being defeated by the latter in August 1921.

Poland defeated Western Ukraine in the Polish-Ukrainian War, but failed against the Bolsheviks in an offensive against Kiev. According to the Peace of Riga, western Ukraine was incorporated into Poland, which in turn recognised the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic in March 1919. With establishment of the Soviet power, Ukraine lost half of its territory, while Moldavian autonomy was established on the left bank of the Dniester River. Ukraine became a founding member of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics in December 1922.[82]

Western Ukraine, Carpathian Ruthenia and Bukovina

The war in Ukraine continued for another two years; by 1921, however, most of Ukraine had been taken over by the Soviet Union, while Galicia and Volhynia (mostly today's West Ukraine) were incorporated into the Second Polish Republic. Modern-day Bukovina was annexed by Romania and Carpathian Ruthenia was admitted to the Czechoslovak Republic as an autonomy.[83]

A powerful underground Ukrainian nationalist movement arose in eastern Poland in the 1920s and 1930s, which was formed by Ukrainian veterans of the Ukrainian-Soviet war (including Yevhen Konovalets, Andriy Melnyk, and Yuriy Tyutyunyk) and was transformed into the Ukrainian Military Organization and later the Organisation of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN). The movement attracted a militant following among students. Hostilities between Polish state authorities and the popular movement led to a substantial number of fatalities, and the autonomy which had been promised was never implemented. The pre-war Polish government also exercised anti-Ukrainian sentiment; it restricted rights of people who declared Ukrainian nationality, belonged to the Eastern Orthodox Church and inhabited the Eastern Borderlands.[84][85] The Ukrainian language was restricted in every field possible, especially in governmental institutions, and the term "Ruthenian" was enforced in an attempt to ban the use of the term "Ukrainian".[86] Despite this, a number of Ukrainian parties, the Ukrainian Catholic Church, an active press, and a business sector existed in Poland. Economic conditions improved in the 1920s, but the region suffered from the Great Depression in the early 1930s.[87]

Inter-war Soviet Ukraine

The Russian Civil War devastated the whole Russian Empire including Ukraine. It left over 1.5 million people dead and hundreds of thousands homeless in the former Russian Empire territory. Soviet Ukraine also faced the Russian famine of 1921 (primarily affecting the Russian Volga-Ural region).[88][89] During the 1920s,[90] under the Ukrainisation policy pursued by the national Communist leadership of Mykola Skrypnyk, Soviet leadership encouraged a national renaissance in the Ukrainian culture and language. Ukrainisation was part of the Soviet-wide policy of Korenisation (literally indigenisation).[82] The Bolsheviks were also committed to universal health care, education and social-security benefits, as well as the right to work and housing.[91] Women's rights were greatly increased through new laws.[92] Most of these policies were sharply reversed by the early 1930s after Joseph Stalin became the de facto communist party leader.

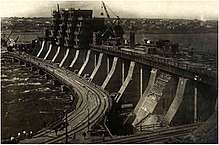

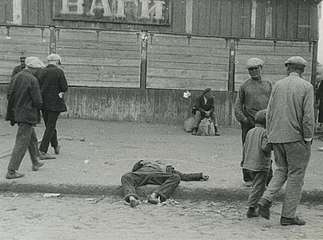

Starting from the late 1920s with a centrally planned economy, Ukraine was involved in Soviet industrialisation and the republic's industrial output quadrupled during the 1930s.[82] The peasantry suffered from the programme of collectivisation of agriculture which began during and was part of the first five-year plan and was enforced by regular troops and secret police.[82] Those who resisted were arrested and deported and agricultural productivity greatly declined. As members of the collective farms were sometimes not allowed to receive any grain until unrealistic quotas were met, millions starved to death in a famine known as the Holodomor or the "Great Famine".[93]

Scholars are divided as to whether this famine fits the definition of genocide, but the Ukrainian parliament and the governments of other countries have acknowledged it as such.[b]

The Communist leadership perceived famine as a means of class struggle and used starvation as a punishment tool to force peasants into collective farms.[94]

Largely the same groups were responsible for the mass killing operations during the civil war, collectivisation, and the Great Terror. These groups were associated with Yefim Yevdokimov (1891–1939) and operated in the Secret Operational Division within General State Political Administration (OGPU) in 1929–31. Yevdokimov transferred into Communist Party administration in 1934, when he became Party secretary for North Caucasus Krai. He appears to have continued advising Joseph Stalin and Nikolai Yezhov on security matters, and the latter relied on Yevdokimov's former colleagues to carry out the mass killing operations that are known as the Great Terror in 1937–38.[95]

On 13 January 2010, Kiev Appellate Court posthumously found Stalin, Kaganovich and other Soviet Communist Party functionaries guilty of genocide against Ukrainians during the Holodomor famine.[96]

World War II

Following the Invasion of Poland in September 1939, German and Soviet troops divided the territory of Poland. Thus, Eastern Galicia and Volhynia with their Ukrainian population became part of Ukraine. For the first time in history, the nation was united.[97][98]

In 1940, the Soviets annexed Bessarabia and northern Bukovina. The Ukrainian SSR incorporated the northern and southern districts of Bessarabia, northern Bukovina, and the Hertsa region. But it ceded the western part of the Moldavian Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic to the newly created Moldavian Soviet Socialist Republic. These territorial gains of the USSR were internationally recognized by the Paris peace treaties of 1947.

German armies invaded the Soviet Union on 22 June 1941, initiating nearly four years of total war. The Axis initially advanced against desperate but unsuccessful efforts of the Red Army. In the encirclement battle of Kiev, the city was acclaimed as a "Hero City", because of its fierce resistance. More than 600,000 Soviet soldiers (or one-quarter of the Soviet Western Front) were killed or taken captive there, with many suffering severe mistreatment.[99][100]

Although the majority of Ukrainians fought in or alongside the Red Army and Soviet resistance,[101] in Western Ukraine an independent Ukrainian Insurgent Army movement arose (UPA, 1942). Created as armed forces of the underground (Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists, OUN)[102][103] which had developed in interwar Poland as a reactionary nationalist organization. During the interwar period, the Polish government's policies towards the Ukrainian minority were initially very accommodating, however by the late 1930s they became increasingly harsh due to civil unrest. Both organizations, OUN and UPA supported the goal of an independent Ukrainian state on the territory with a Ukrainian ethnic majority. Although this brought conflict with Nazi Germany, at times the Melnyk wing of the OUN allied with the Nazi forces. Also, UPA divisions carried out massacres of ethnic Poles, killing around 100,000 Polish civilians,[104] which brought reprisals.[105] After the war, the UPA continued to fight the USSR until the 1950s.[106][107] At the same time, the Ukrainian Liberation Army, another nationalist movement, fought alongside the Nazis.

In total, the number of ethnic Ukrainians who fought in the ranks of the Soviet Army is estimated from 4.5 million[101] to 7 million.[108][c] The pro-Soviet partisan guerrilla resistance in Ukraine is estimated to number at 47,800 from the start of occupation to 500,000 at its peak in 1944, with about 50% being ethnic Ukrainians.[109] Generally, the Ukrainian Insurgent Army's figures are unreliable, with figures ranging anywhere from 15,000 to as many as 100,000 fighters.[110][111]

Most of the Ukrainian SSR was organised within the Reichskommissariat Ukraine, with the intention of exploiting its resources and eventual German settlement. Some western Ukrainians, who had only joined the Soviet Union in 1939, hailed the Germans as liberators. Brutal German rule eventually turned their supporters against the Nazi administrators, who made little attempt to exploit dissatisfaction with Stalinist policies.[112] Instead, the Nazis preserved the collective-farm system, carried out genocidal policies against Jews, deported millions of people to work in Germany, and began a depopulation program to prepare for German colonisation.[112] They blockaded the transport of food on the Kiev River.[113]

The vast majority of the fighting in World War II took place on the Eastern Front.[114] By some estimates, 93% of all German casualties took place there.[115] The total losses inflicted upon the Ukrainian population during the war are estimated at about 6 million,[116][117] including an estimated one and a half million Jews killed by the Einsatzgruppen,[118] sometimes with the help of local collaborators. Of the estimated 8.6 million Soviet troop losses,[119][120][121] 1.4 million were ethnic Ukrainians.[119][121][c][d] Victory Day is celebrated as one of ten Ukrainian national holidays.[122]

Post-World War II

The republic was heavily damaged by the war, and it required significant efforts to recover. More than 700 cities and towns and 28,000 villages were destroyed.[123] The situation was worsened by a famine in 1946–47, which was caused by a drought and the wartime destruction of infrastructure. The death toll of this famine varies, with even the lowest estimate in the tens of thousands.[124][125][126] In 1945, the Ukrainian SSR became one of the founding members of the United Nations organization,[127] part of a special agreement at the Yalta Conference.[128]

Post-war ethnic cleansing occurred in the newly expanded Soviet Union. As of 1 January 1953, Ukrainians were second only to Russians among adult "special deportees", comprising 20% of the total.[129] In addition, over 450,000 ethnic Germans from Ukraine and more than 200,000 Crimean Tatars were victims of forced deportations.[129]

Following the death of Stalin in 1953, Nikita Khrushchev became the new leader of the USSR. Having served as First Secretary of the Communist Party of Ukrainian SSR in 1938–49, Khrushchev was intimately familiar with the republic; after taking power union-wide, he began to emphasize "the friendship" between the Ukrainian and Russian nations. In 1954, the 300th anniversary of the Treaty of Pereyaslav was widely celebrated. Crimea was transferred from the Russian SFSR to the Ukrainian SSR.[130]

By 1950, the republic had fully surpassed pre-war levels of industry and production.[131] During the 1946–1950 five-year plan, nearly 20% of the Soviet budget was invested in Soviet Ukraine, a 5% increase from pre-war plans. As a result, the Ukrainian workforce rose 33.2% from 1940 to 1955 while industrial output grew 2.2 times in that same period.

Soviet Ukraine soon became a European leader in industrial production,[132] and an important centre of the Soviet arms industry and high-tech research. Such an important role resulted in a major influence of the local elite. Many members of the Soviet leadership came from Ukraine, most notably Leonid Brezhnev. He later ousted Khrushchev and became the Soviet leader from 1964 to 1982. Many prominent Soviet sports players, scientists, and artists came from Ukraine.

On 26 April 1986, a reactor in the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant exploded, resulting in the Chernobyl disaster, the worst nuclear reactor accident in history.[133] This was the only accident to receive the highest possible rating of 7 by the International Nuclear Event Scale, indicating a "major accident", until the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster in March 2011.[134] At the time of the accident, 7 million people lived in the contaminated territories, including 2.2 million in Ukraine.[135]

After the accident, the new city of Slavutych was built outside the exclusion zone to house and support the employees of the plant, which was decommissioned in 2000. A report prepared by the International Atomic Energy Agency and World Health Organization attributed 56 direct deaths to the accident and estimated that there may have been 4,000 extra cancer deaths.[136]

Independence

On 16 July 1990, the new parliament adopted the Declaration of State Sovereignty of Ukraine.[137] This established the principles of the self-determination, democracy, independence, and the priority of Ukrainian law over Soviet law. A month earlier, a similar declaration was adopted by the parliament of the Russian SFSR. This started a period of confrontation with the central Soviet authorities. In August 1991, a faction among the Communist leaders of the Soviet Union attempted a coup to remove Mikhail Gorbachev and to restore the Communist party's power. After it failed, on 24 August 1991 the Ukrainian parliament adopted the Act of Independence.[138]

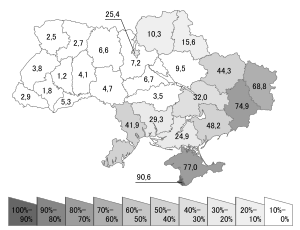

A referendum and the first presidential elections took place on 1 December 1991. More than 90% of the electorate expressed their support for the Act of Independence, and they elected the chairman of the parliament, Leonid Kravchuk as the first President of Ukraine. At the meeting in Brest, Belarus on 8 December, followed by the Alma Ata meeting on 21 December, the leaders of Belarus, Russia, and Ukraine formally dissolved the Soviet Union and formed the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS).[139] On 26 December 1991 the Council of Republics of the USSR Supreme Council adapted declaration "In regards to creation of the Commonwealth of Independent States" (Russian: В связи с созданием Содружества Независимых Государств) which de jure dissolved the Soviet Union and the Soviet flag was lowered over the Kremlin.[140]

Ukraine was initially viewed as having favourable economic conditions in comparison to the other regions of the Soviet Union.[141] However, the country experienced deeper economic slowdown than some of the other former Soviet Republics. During the recession, Ukraine lost 60% of its GDP from 1991 to 1999,[142][143] and suffered five-digit inflation rates.[144] Dissatisfied with the economic conditions, as well as the amounts of crime and corruption in Ukraine, Ukrainians protested and organized strikes.[145]

The Ukrainian economy stabilized by the end of the 1990s. A new currency, the hryvnia, was introduced in 1996. After 2000, the country enjoyed steady real economic growth averaging about seven percent annually.[146][147] A new Constitution of Ukraine was adopted under second President Leonid Kuchma in 1996, which turned Ukraine into a semi-presidential republic and established a stable political system. Kuchma was, however, criticised by opponents for corruption, electoral fraud, discouraging free speech and concentrating too much power in his office.[148] Ukraine also pursued full nuclear disarmament, giving up the third largest nuclear weapons stockpile in the world and dismantling or removing all strategic bombers on its territory in exchange for various assurances (main article: Nuclear weapons and Ukraine).[149]

Orange Revolution

In 2004, Viktor Yanukovych, then Prime Minister, was declared the winner of the presidential elections, which had been largely rigged, as the Supreme Court of Ukraine later ruled.[150] The results caused a public outcry in support of the opposition candidate, Viktor Yushchenko, who challenged the outcome. During the tumultuous months of the revolution, candidate Yushchenko suddenly became gravely ill, and was soon found by multiple independent physician groups to have been poisoned by TCDD dioxin.[151][152] Yushchenko strongly suspected Russian involvement in his poisoning.[153] All of this eventually resulted in the peaceful Orange Revolution, bringing Viktor Yushchenko and Yulia Tymoshenko to power, while casting Viktor Yanukovych in opposition.[154]

.jpg)

Activists of the Orange Revolution were funded and trained in tactics of political organisation and nonviolent resistance by Western pollsters and professional consultants who were partly funded by Western government and non-government agencies but received most of their funding from domestic sources.[nb 1][155] According to The Guardian, the foreign donors included the U.S. State Department and USAID along with the National Democratic Institute for International Affairs, the International Republican Institute, the NGO Freedom House and George Soros's Open Society Institute.[156] The National Endowment for Democracy has supported democracy-building efforts in Ukraine since 1988.[157] Writings on nonviolent struggle by Gene Sharp contributed in forming the strategic basis of the student campaigns.[158]

Russian authorities provided support through advisers such as Gleb Pavlovsky, consulting on blackening the image of Yushchenko through the state media, pressuring state-dependent voters to vote for Yanukovych and on vote-rigging techniques such as multiple 'carousel voting' and 'dead souls' voting.[155]

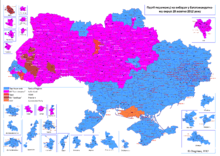

Yanukovych returned to power in 2006 as Prime Minister in the Alliance of National Unity,[159] until snap elections in September 2007 made Tymoshenko Prime Minister again.[160] Amid the 2008–09 Ukrainian financial crisis the Ukrainian economy plunged by 15%.[161] Disputes with Russia briefly stopped all gas supplies to Ukraine in 2006 and again in 2009, leading to gas shortages in other countries.[162][163] Viktor Yanukovych was elected President in 2010 with 48% of votes.[164]

Euromaidan and 2014 revolution

The Euromaidan (Ukrainian: Євромайдан, literally "Eurosquare") protests started in November 2013 after the president, Viktor Yanukovych, began moving away from an association agreement that had been in the works with the European Union and instead chose to establish closer ties with the Russian Federation.[165][166][167] Some Ukrainians took to the streets to show their support for closer ties with Europe.[168] Meanwhile, in the predominantly Russian-speaking east, a large portion of the population opposed the Euromaidan protests, instead supporting the Yanukovych government.[169] Over time, Euromaidan came to describe a wave of demonstrations and civil unrest in Ukraine,[170] the scope of which evolved to include calls for the resignation of President Yanukovych and his government.[171]

Violence escalated after 16 January 2014 when the government accepted new Anti-Protest Laws. Violent anti-government demonstrators occupied buildings in the centre of Kiev, including the Justice Ministry building, and riots left 98 dead with approximately fifteen thousand injured and 100 considered missing[172][173][174][175] from 18 to 20 February.[176][177] On 21 February, President Yanukovych signed a compromise deal with opposition leaders that promised constitutional changes to restore certain powers to Parliament and called for early elections to be held by December.[178] However, Members of Parliament voted on 22 February to remove the president and set an election for 25 May to select his replacement.[179] Petro Poroshenko, running on a pro-European Union platform, won with over fifty percent of the vote, therefore not requiring a run-off election.[180][181][182] Upon his election, Poroshenko announced that his immediate priorities would be to take action in the civil unrest in Eastern Ukraine and mend ties with the Russian Federation.[180][181][182] Poroshenko was inaugurated as president on 7 June 2014, as previously announced by his spokeswoman Irina Friz in a low-key ceremony without a celebration on Kiev's Maidan Nezalezhnosti (Independence Square, the centre of the Euromaidan protests[183]) for the ceremony.[184][185] In October 2014 Parliament elections, Petro Poroshenko Bloc "Solidarity" won 132 of the 423 contested seats.[186]

Civil unrest, Russian intervention, and annexation of Crimea

The ousting[187] of Yanukovych prompted Vladimir Putin to begin preparations to annex Crimea on 23 February 2014.[188][189] Using the Russian naval base at Sevastopol as cover, Putin directed Russian troops and intelligence agents to disarm Ukrainian forces and take control of Crimea.[190][191][192][193] After the troops entered Crimea,[194] a controversial referendum was held on 16 March 2014 and the official result was that 97 percent wished to join with Russia.[195] On 18 March 2014, Russia and the self-proclaimed Republic of Crimea signed a treaty of accession of the Republic of Crimea and Sevastopol in the Russian Federation. The UN general assembly responded by passing resolution 68/262 that the referendum was invalid and supporting the territorial integrity of Ukraine.[196]

Separately, in the Donetsk and Luhansk regions, armed men declaring themselves as local militia supported with pro-Russian protesters[197] seized government buildings, police and special police stations in several cities and held unrecognised status referendums.[198] The insurgency was led by Russian emissaries Igor Girkin[199] and Alexander Borodai[200] as well as militants from Russia, such as Arseny Pavlov.[201]

Talks in Geneva between the EU, Russia, Ukraine and USA yielded a Joint Diplomatic Statement referred to as the 2014 Geneva Pact[202] in which the parties requested that all unlawful militias lay down their arms and vacate seized government buildings, and also establish a political dialogue that could lead to more autonomy for Ukraine's regions. When Petro Poroshenko won the presidential election held on 25 May 2014, he vowed to continue the military operations by the Ukrainian government forces to end the armed insurgency.[203] More than 9,000 people have been killed in the military campaign.

In August 2014, a bilateral commission of leading scholars from the United States and Russia issued the Boisto Agenda indicating a 24-step plan to resolve the crisis in Ukraine.[204] The Boisto Agenda was organized into five imperative categories for addressing the crisis requiring stabilization identified as: (1) Elements of an Enduring, Verifiable Ceasefire; (2) Economic Relations; (3) Social and Cultural Issues; (4) Crimea; and, (5) International Status of Ukraine.[204] In late 2014, Ukraine ratified the Ukraine–European Union Association Agreement, which Poroshenko described as Ukraine's "first but most decisive step" towards EU membership.[205] Poroshenko also set 2020 as the target for EU membership application.[206]

.jpg)

In February 2015, after a summit hosted in Belarus, Poroshenko negotiated a ceasefire with the separatist troops. This included conditions such as the withdrawal of heavy weaponry from the front line and decentralisation of rebel regions by the end of 2015. It also included conditions such as Ukrainian control of the border with Russia in 2015 and the withdrawal of all foreign troops from Ukrainian territory. The ceasefire began at midnight on 15 February 2015. Participants in this ceasefire also agreed to attend regular meetings to ensure that the agreement is respected.[207]

On 1 January 2016, Ukraine joined the Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Area with European Union,[14] which aims to modernize and develop Ukraine's economy, governance and rule of law to EU standards and gradually increase integration with the EU Internal market.[208] Then, on 11 May 2017 the European Union approved visa-free travel for Ukrainian citizens: this took effect from 11 June entitling Ukrainians to travel to the Schengen area for tourism, family visits and business reasons, with the only document required being a valid biometric passport.[209]

COVID-19

The first case of COVID-19 in Ukraine was recorded on 3 March.[210] On 13 March, the National Bank of Ukraine cut interest rates from 11% to 10% to help stop the coronavirus panic.[211] On 17 March the passage of Law No. 3219, "On Amending Certain Legislative Acts of Ukraine aimed at Preventing the Occurrence and Spread of Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19)" modified the Criminal Code of Ukraine to include rules of behaviour designed to halt the spread of the disease,[212][213] and attributed the measures in law to force majeure;[212] a total of 344 deputies out of 450 in the Verkhovna Rada voted in favour of Law No. 3219.[212] On 17 March, the international border was closed to foreigners.[214] Other measures included shuttering, at least until 3 April, all "cafes, restaurants, gyms, shopping malls, and entertainment venues",[214] the Ukrzaliznytsia passenger rail service,[215] all domestic flights, and public intercity transportation such as the metro in Kiev, Dnipro, and Kharkiv.[214] The ban on travel in the Kiev metro caused chaos, as commuters were forced to assemble instead at bus stops.[216] The government also placed on the right to assembly a limit of 10 individuals.[214] As of 19 March, the number of infections had risen to 21, and three deaths had been reported.[214] On 22 March, Zelensky asked IMF Managing Director Kristalina Georgieva for permission to participate in the $1 trillion IMF coronavirus bailout fund.[217]

On 29 May, Ukraine opened its borders with its neighbours in the EU and Moldova, but not with Belarus and Russia.[218]

Geography

At 603,628 square kilometres (233,062 sq mi) and with a coastline of 2,782 kilometres (1,729 mi), Ukraine is the second-largest country by area in Europe, and the world's 46th-largest country.[41] It lies between latitudes 44° and 53° N, and longitudes 22° and 41° E.

The landscape of Ukraine consists mostly of fertile plains (or steppes) and plateaus, crossed by rivers such as the Dnieper (Dnipro), Seversky Donets, Dniester and the Southern Bug as they flow south into the Black Sea and the smaller Sea of Azov. To the southwest, the delta of the Danube forms the border with Romania. Ukraine's various regions have diverse geographic features ranging from the highlands to the lowlands. The country's only mountains are the Carpathian Mountains in the west, of which the highest is the Hora Hoverla at 2,061 metres (6,762 ft), and the Crimean Mountains on Crimea, in the extreme south along the coast.[219] However Ukraine also has a number of highland regions such as the Volyn-Podillia Upland (in the west) and the Near-Dnipro Upland (on the right bank of Dnieper); to the east there are the south-western spurs of the Central Russian Upland over which runs the border with the Russian Federation. Near the Sea of Azov can be found the Donets Ridge and the Near Azov Upland. The snow melt from the mountains feeds the rivers, and natural changes in altitude form sudden drops in elevation and give rise to waterfalls.

Significant natural resources in Ukraine include iron ore, coal, manganese, natural gas, oil, salt, sulphur, graphite, titanium, magnesium, kaolin, nickel, mercury, timber and an abundance of arable land. Despite this, the country faces a number of major environmental issues such as inadequate supplies of potable water; air- and water-pollution and deforestation, as well as radiation contamination in the north-east from the 1986 accident at the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant. Recycling toxic household waste is still in its infancy in Ukraine.[220]

Soil

From northwest to southeast the soils of Ukraine may be divided into three major aggregations:[221]

- a zone of sandy podzolized soils

- a central belt consisting of the extremely fertile Ukrainian black earth (chernozems)

- a zone of chestnut and salinized soils

As much as two-thirds of the country's surface land consists of the so-called black earth, a resource that has made Ukraine one of the most fertile regions in the world and well known as a "breadbasket".[222] These soils may be divided into three broad groups:

- in the north a belt of the so-called deep chernozems, about 5 feet (1.5 metres) thick and rich in humus

- south and east of the former, a zone of prairie, or ordinary, chernozems, which are equally rich in humus but only about 3 feet (0.91 metres) thick

- the southernmost belt, which is even thinner and has still less humus

Interspersed in various uplands and along the northern and western perimeters of the deep chernozems are mixtures of gray forest soils and podzolized black-earth soils, which together occupy much of Ukraine's remaining area. All these soils are very fertile when sufficient water is available. However, their intensive cultivation, especially on steep slopes, has led to widespread soil erosion and gullying.

The smallest proportion of the soil cover consists of the chestnut soils of the southern and eastern regions. They become increasingly salinized to the south as they approach the Black Sea.[221]

Climate

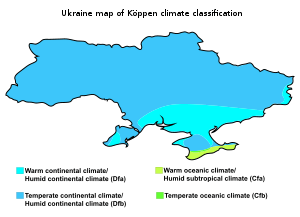

Ukraine has a mostly temperate climate, with the exception of the southern coast of Crimea which has a subtropical climate.[223] The climate is influenced by moderately warm, humid air coming from the Atlantic Ocean.[224] Average annual temperatures range from 5.5–7 °C (41.9–44.6 °F) in the north, to 11–13 °C (51.8–55.4 °F) in the south.[224] Precipitation is disproportionately distributed; it is highest in the west and north and lowest in the east and southeast.[224] Western Ukraine, particularly in the Carpathian Mountains, receives around 1,200 millimetres (47.2 in) of precipitation annually, while Crimea and the coastal areas of the Black Sea receive around 400 millimetres (15.7 in).[224]

Biodiversity

Ukraine is home to a diverse assemblage of animals, fungi, microorganisms and plants.

Animals

Ukraine is divided into two main zoological areas. One of these areas, in the west of the country, is made up of the borderlands of Europe, where there are species typical of mixed forests, the other is located in eastern Ukraine, where steppe-dwelling species thrive. In the forested areas of the country it is not uncommon to find lynxes, wolves, wild boar and martens, as well as many other similar species; this is especially true of the Carpathian Mountains, where many predatory mammals make their home, as well as a contingent of brown bears. Around Ukraine's lakes and rivers beavers, otters and mink make their home, whilst in the waters carp, bream and catfish are the most commonly found species of fish. In the central and eastern parts of the country, rodents such as hamsters and gophers are found in large numbers.

Fungi

More than 6,600 species of fungi (including lichen-forming species) have been recorded from Ukraine,[225][226] but this number is far from complete. The true total number of fungal species occurring in Ukraine, including species not yet recorded, is likely to be far higher, given the generally accepted estimate that only about 7% of all fungi worldwide have so far been discovered.[227] Although the amount of available information is still very small, a first effort has been made to estimate the number of fungal species endemic to Ukraine, and 2217 such species have been tentatively identified.[228]

Politics

Ukraine is a republic under a mixed semi-parliamentary semi-presidential system with separate legislative, executive, and judicial branches.

Constitution of Ukraine

With the proclamation of its independence on 24 August 1991, and adoption of a constitution on 28 June 1996, Ukraine became a semi-presidential republic. However, in 2004, deputies introduced changes to the Constitution, which tipped the balance of power in favour of a parliamentary system. From 2004 to 2010, the legitimacy of the 2004 Constitutional amendments had official sanction, both with the Constitutional Court of Ukraine, and most major political parties.[233] Despite this, on 30 September 2010 the Constitutional Court ruled that the amendments were null and void, forcing a return to the terms of the 1996 Constitution and again making Ukraine's political system more presidential in character.

The ruling on the 2004 Constitutional amendments became a major topic of political discourse. Much of the concern was based on the fact that neither the Constitution of 1996 nor the Constitution of 2004 provided the ability to "undo the Constitution", as the decision of the Constitutional Court would have it, even though the 2004 constitution arguably has an exhaustive list of possible procedures for constitutional amendments (articles 154–159). In any case, the current Constitution could be modified by a vote in Parliament.[233][234][235]

On 21 February 2014 an agreement between President Viktor Yanukovych and opposition leaders saw the country return to the 2004 Constitution. The historic agreement, brokered by the European Union, followed protests that began in late November 2013 and culminated in a week of violent clashes in which scores of protesters were killed. In addition to returning the country to the 2004 Constitution, the deal provided for the formation of a coalition government, the calling of early elections, and the release of former Prime Minister Yulia Tymoshenko from prison.[236] A day after the agreement was reached the Ukraine parliament dismissed Yanukovych and installed its speaker Oleksandr Turchynov as interim president[237] and Arseniy Yatsenyuk as the Prime Minister of Ukraine.[238]

President, parliament and government

|

.jpg) |

| Volodymyr Zelensky President |

Denys Shmyhal Prime Minister |

The President is elected by popular vote for a five-year term and is the formal head of state.[239] Ukraine's legislative branch includes the 450-seat unicameral parliament, the Verkhovna Rada.[240] The parliament is primarily responsible for the formation of the executive branch and the Cabinet of Ministers, headed by the Prime Minister.[241] However, the President still retains the authority to nominate the Ministers of the Foreign Affairs and of Defence for parliamentary approval, as well as the power to appoint the Prosecutor General and the head of the Security Service.

Laws, acts of the parliament and the cabinet, presidential decrees, and acts of the Crimean parliament may be abrogated by the Constitutional Court, should they be found to violate the constitution. Other normative acts are subject to judicial review. The Supreme Court is the main body in the system of courts of general jurisdiction. Local self-government is officially guaranteed. Local councils and city mayors are popularly elected and exercise control over local budgets. The heads of regional and district administrations are appointed by the President in accordance with the proposals of the Prime Minister. This system virtually requires an agreement between the President and the Prime Minister, and has in the past led to problems, such as when President Yushchenko exploited a perceived loophole by appointing so-called 'temporarily acting' officers, instead of actual governors or local leaders, thus evading the need to seek a compromise with the Prime Minister. This practice was controversial and was subject to Constitutional Court review.

Ukraine has many political parties, many of which have tiny memberships and are unknown to the general public. Small parties often join in multi-party coalitions (electoral blocs) for the purpose of participating in parliamentary elections.

Courts and law enforcement

The courts enjoy legal, financial and constitutional freedom guaranteed by Ukrainian law since 2002. Judges are largely well protected from dismissal (except in the instance of gross misconduct). Court justices are appointed by presidential decree for an initial period of five years, after which Ukraine's Supreme Council confirms their positions for life. Although there are still problems, the system is considered to have been much improved since Ukraine's independence in 1991. The Supreme Court is regarded as an independent and impartial body, and has on several occasions ruled against the Ukrainian government. The World Justice Project ranks Ukraine 66 out of 99 countries surveyed in its annual Rule of Law Index.[242]

Prosecutors in Ukraine have greater powers than in most European countries, and according to the European Commission for Democracy through Law 'the role and functions of the Prosecutor's Office is not in accordance with Council of Europe standards".[243] The criminal judicial system maintains an average conviction rate of over 99%,[244] equal to the conviction rate of the Soviet Union, with[245] suspects often being incarcerated for long periods before trial.[246] On 24 March 2010, President Yanukovych formed an expert group to make recommendations how to "clean up the current mess and adopt a law on court organization".[246] One day later, he stated "We can no longer disgrace our country with such a court system."[246] The criminal judicial system and the prison system of Ukraine remain quite punitive.

Since 1 January 2010 it has been permissible to hold court proceedings in Russian by mutual consent of the parties. Citizens unable to speak Ukrainian or Russian may use their native language or the services of a translator.[247][248] Previously all court proceedings had to be held in Ukrainian.

Law enforcement agencies in Ukraine are organised under the authority of the Ministry of Internal Affairs. They consist primarily of the national police force (Мiлiцiя) and various specialised units and agencies such as the State Border Guard and the Coast Guard services. Law enforcement agencies, particularly the police, faced criticism for their heavy handling of the 2004 Orange Revolution. Many thousands of police officers were stationed throughout the capital, primarily to dissuade protesters from challenging the state's authority but also to provide a quick reaction force in case of need; most officers were armed.[249] Bloodshed was only avoided when Lt. Gen. Sergei Popkov heeded his colleagues' calls to withdraw.

The Ministry of Internal Affairs is also responsible for the maintenance of the State Security Service; Ukraine's domestic intelligence agency, which has on occasion been accused of acting like a secret police force serving to protect the country's political elite from media criticism. On the other hand, however, it is widely accepted that members of the service provided vital information about government plans to the leaders of the Orange Revolution to prevent the collapse of the movement.

Foreign relations

In 1999–2001, Ukraine served as a non-permanent member of the UN Security Council. Historically, Soviet Ukraine joined the United Nations in 1945 as one of the original members following a Western compromise with the Soviet Union, which had asked for seats for all 15 of its union republics. Ukraine has consistently supported peaceful, negotiated settlements to disputes. It has participated in the quadripartite talks on the conflict in Moldova and promoted a peaceful resolution to conflict in the post-Soviet state of Georgia. Ukraine also has made a substantial contribution to UN peacekeeping operations since 1992.

Ukraine currently considers Euro-Atlantic integration its primary foreign policy objective,[250] but in practice it has always balanced its relationship with the European Union and the United States with strong ties to Russia. The European Union's Partnership and Cooperation Agreement (PCA) with Ukraine went into force on 1 March 1998. The European Union (EU) has encouraged Ukraine to implement the PCA fully before discussions begin on an association agreement, issued at the EU Summit in December 1999 in Helsinki, recognizes Ukraine's long-term aspirations but does not discuss association. On 31 January 1992, Ukraine joined the then-Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe (now the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE)), and on 10 March 1992, it became a member of the North Atlantic Cooperation Council. Ukraine–NATO relations are close and the country has declared interest in eventual membership.[250] This was removed from the government's foreign policy agenda upon election of Viktor Yanukovych to the presidency, in 2010.[250] But after February 2014's Yanukovych ouster and the (denied by Russia) following Russian military intervention in Ukraine Ukraine renewed its drive for NATO membership.[250] Ukraine is the most active member of the Partnership for Peace (PfP). All major political parties in Ukraine support full eventual integration into the European Union. The Association Agreement with the EU was expected to be signed and put into effect by the end of 2011, but the process was suspended by 2012 because of the political developments of that time.[251] The Association Agreement between Ukraine and the European Union was signed in 2014.[252]

Ukraine long had close ties with all its neighbours, but Russia–Ukraine relations became difficult in 2014 by the annexation of Crimea, energy dependence and payment disputes. There are also tensions with Poland[253] and Hungary.[254]

The Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Area (DCFTA), which entered into force in January 2016 following the ratification of the Ukraine–European Union Association Agreement, formally integrates Ukraine into the European Single Market and the European Economic Area.[255][256] Ukraine receives further support and assistance for its EU-accession aspirations from the International Visegrád Fund of the Visegrád Group that consists of Central European EU members the Czech Republic, Poland, Hungary and Slovakia.[257]

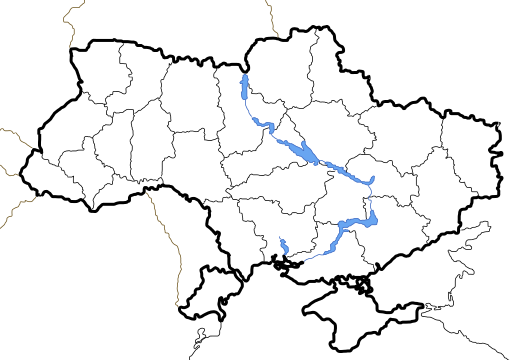

Administrative divisions

The system of Ukrainian subdivisions reflects the country's status as a unitary state (as stated in the country's constitution) with unified legal and administrative regimes for each unit.

Including Sevastopol and the Autonomous Republic of Crimea that were annexed by the Russian Federation in 2014, Ukraine consists of 27 regions: twenty-four oblasts (provinces), one autonomous republic (Autonomous Republic of Crimea), and two cities of special status – Kiev, the capital, and Sevastopol. The 24 oblasts and Crimea are subdivided into 136[258] raions (districts) and city municipalities of regional significance, or second-level administrative units.

Populated places in Ukraine are split into two categories: urban and rural. Urban populated places are split further into cities and urban-type settlements (a Soviet administrative invention), while rural populated places consist of villages and settlements (a generally used term). All cities have certain degree of self-rule depending on their significance such as national significance (as in the case of Kiev and Sevastopol), regional significance (within each oblast or autonomous republic) or district significance (all the rest of cities). A city's significance depends on several factors such as its population, socio-economic and historical importance, infrastructure and others.

|

| |

Armed forces

After the dissolution of the Soviet Union, Ukraine inherited a 780,000-man military force on its territory, equipped with the third-largest nuclear weapons arsenal in the world.[259][260] In May 1992, Ukraine signed the Lisbon Protocol in which the country agreed to give up all nuclear weapons to Russia for disposal and to join the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty as a non-nuclear weapon state. Ukraine ratified the treaty in 1994, and by 1996 the country became free of nuclear weapons.[259]

Ukraine took consistent steps toward reduction of conventional weapons. It signed the Treaty on Conventional Armed Forces in Europe, which called for reduction of tanks, artillery, and armoured vehicles (army forces were reduced to 300,000). The country plans to convert the current conscript-based military into a professional volunteer military.[261]

Ukraine has been playing an increasingly larger role in peacekeeping operations. On Friday 3 January 2014, the Ukrainian frigate Hetman Sagaidachniy joined the European Union's counter piracy Operation Atalanta and will be part of the EU Naval Force off the coast of Somalia for two months.[262] Ukrainian troops are deployed in Kosovo as part of the Ukrainian-Polish Battalion.[263] A Ukrainian unit was deployed in Lebanon, as part of UN Interim Force enforcing the mandated ceasefire agreement. There was also a maintenance and training battalion deployed in Sierra Leone. In 2003–05, a Ukrainian unit was deployed as part of the Multinational force in Iraq under Polish command. The total Ukrainian armed forces deployment around the world is 562 servicemen.[264]

Military units of other states participate in multinational military exercises with Ukrainian forces in Ukraine regularly, including U.S. military forces.[265]

Following independence, Ukraine declared itself a neutral state.[13] The country has had a limited military partnership with Russian Federation, other CIS countries and a partnership with NATO since 1994. In the 2000s, the government was leaning towards NATO, and a deeper cooperation with the alliance was set by the NATO-Ukraine Action Plan signed in 2002. It was later agreed that the question of joining NATO should be answered by a national referendum at some point in the future.[261] Recently deposed President Viktor Yanukovych considered the current level of co-operation between Ukraine and NATO sufficient, and was against Ukraine joining NATO. During the 2008 Bucharest summit, NATO declared that Ukraine would eventually become a member of NATO when it meets the criteria for the accession.

Economy

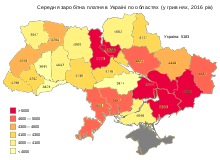

_in_2016.png)

In Soviet times, the economy of Ukraine was the second largest in the Soviet Union, being an important industrial and agricultural component of the country's planned economy.[41] With the dissolution of the Soviet system, the country moved from a planned economy to a market economy. The transition was difficult for the majority of the population which plunged into poverty.[266] Ukraine's economy contracted severely in the years after the Soviet dissolution. Day-to-day life for the average person living in Ukraine was a struggle. A significant number of citizens in rural Ukraine survived by growing their own food, often working two or more jobs and buying the basic necessities through the barter economy.[267]

In 1991, the government liberalised most prices to combat widespread product shortages, and was successful in overcoming the problem. At the same time, the government continued to subsidise state-run industries and agriculture by uncovered monetary emission. The loose monetary policies of the early 1990s pushed inflation to hyperinflationary levels. For the year 1993, Ukraine holds the world record for inflation in one calendar year.[268] Those living on fixed incomes suffered the most.[82] Prices stabilised only after the introduction of new currency, the hryvnia, in 1996. The country was also slow in implementing structural reforms. Following independence, the government formed a legal framework for privatisation. However, widespread resistance to reforms within the government and from a significant part of the population soon stalled the reform efforts. Many state-owned enterprises were exempt from privatisation.

In the meantime, by 1999, the GDP had fallen to less than 40% of the 1991 level.[269] It recovered considerably in the following years.[270] [271] Ukraine was hit by the economic crisis of 2008 and in November 2008, the IMF approved a stand-by loan of $16.5 billion for the country.[272]

In 2019 the average nominal salary in Ukraine reached 10,000 hryvnias per month or around €300[273], while in 2018, Ukraine's median wealth per adult was $40.[15] In 2017, Ukraine's government debt was 75%.[274]

Ukraine produces nearly all types of transportation vehicles and spacecraft. Antonov airplanes and KrAZ trucks are exported to many countries. The majority of Ukrainian exports are marketed to the European Union and CIS.[275] Since independence, Ukraine has maintained its own space agency, the National Space Agency of Ukraine (NSAU). Ukraine became an active participant in scientific space exploration and remote sensing missions. Between 1991 and 2007, Ukraine has launched six self made satellites and 101 launch vehicles, and continues to design spacecraft.[276][277][278]

The country imports most energy supplies, especially oil and natural gas and, to a large extent, depends on Russia as its energy supplier. While 25% of the natural gas in Ukraine comes from internal sources, about 35% comes from Russia and the remaining 40% from Central Asia through transit routes that Russia controls. At the same time, 85% of the Russian gas is delivered to Western Europe through Ukraine.[279]

Growing sectors of the Ukrainian economy include the information technology (IT) market.[280] In 2013, Ukraine ranked fourth in the world in number of certified IT professionals after the United States, India and Russia.[281]

Ukraine's 2010 GDP, as calculated by the World Bank, was around $136 billion, 2011 GDP – around $163 billion, 2012 – $176.6 billion, 2013 – $177.4 billion.[282] In 2014 and 2015, the Ukrainian currency was the world's worst performing currency, having dropped 80 percent of its value since April 2014 since the War in Donbass and the annexation of Crimea by Russia.[283][284]

The World Bank classifies Ukraine as a middle-income state.[285] Significant issues include underdeveloped infrastructure and transportation, corruption and bureaucracy. The public will to fight against corrupt officials and business elites culminated in a strong wave of public demonstrations against the Victor Yanukovych's regime in November 2013.[286] According to Transparency International's Corruption Perceptions Index, Ukraine was ranked 120th with a score of 32 out of 100 in 2018.[287] In the first quarter of 2017, the level of shadow economy in Ukraine amounted to 37% of GDP.[288]

In the 2000s Ukraine managed to achieve certain progress in reducing absolute poverty, ensuring access to primary and secondary education, improving maternal health and reducing child mortality.[289]

The economy of Ukraine overcame the heavy crisis caused by armed conflict in southeast part of country. At the same time, 200% devaluation of Ukrainian hryvnia (national currency) in 2014–2015 made Ukrainian goods and services cheaper and more сompetitive.[290] In 2016, for the first time since 2010, the economy grew more than 2%. According to World Bank statement growth is projected at 2% in 2017 and 3.5% in 2018.

As of 2017, according to major economic classifications of countries such as gross domestic product (at purchasing power parity) or the Human Development Index, Ukraine is the second poorest country in Europe, after Moldova.[291][292] Ukraine has one of the most equal income distribution as measured by the Gini index and Palma ratio.[293]

Corporations

Ukraine has a very large heavy-industry base and is one of the largest refiners of metallurgical products in Eastern Europe.[294] However, the country is also well known for its production of high-technological goods and transport products, such as Antonov aircraft and various private and commercial vehicles.[295] The country's largest and most competitive firms are components of the PFTS index, traded on the PFTS Ukraine Stock Exchange.

Well-known Ukrainian brands include Naftogaz Ukrainy, AvtoZAZ, PrivatBank, Roshen, Yuzhmash, Nemiroff, Motor Sich, Khortytsa, Kyivstar and Aerosvit.[296]

Ukraine is regarded as a developing economy with high potential for future success, though such a development is thought likely only with new all-encompassing economic and legal reforms.[297] Although Foreign Direct Investment in Ukraine remained relatively strong since recession of the early 1990s, the country has had trouble maintaining stable economic growth. The reasons are the takeover and monopolisation of traditional heavy industries by wealthy individuals such as Rinat Akhmetov, the enduring failure to broaden the nation's economic base and a lack of effective legal protection for investors and their products.[298]

Transport

.jpg)

In total, Ukrainian paved roads stretch for 164,732 kilometres (102,360 mi).[41] Major routes, marked with the letter 'M' for 'International' (Ukrainian: Міжнародний), extend nationwide and connect all major cities of Ukraine, and provide cross-border routes to the country's neighbours. There are only two true motorway standard highways in Ukraine; a 175-kilometre (109-mile) stretch of motorway from Kharkiv to Dnipro and a section of the M03 which extends 18 km (11 mi) from Kiev to Boryspil, where the city's international airport is located.

Rail transport in Ukraine connects all major urban areas, port facilities and industrial centres with neighbouring countries. The heaviest concentration of railway track is the Donbas region of Ukraine. Although rail freight transport fell in the 1990s, Ukraine is still one of the world's highest rail users.[299] The total amount of railroad track in Ukraine extends for 22,473 kilometres (13,964 mi), of which 9,250 kilometres (5,750 mi) was electrified in the 2000s.[41] Currently the state has a monopoly on the provision of passenger rail transport, and all trains, other than those with cooperation of other foreign companies on international routes, are operated by its company 'Ukrzaliznytsia.

_Ukraine.jpg)

Transport by air is developing quickly, with a visa-free programme for EU nationals and citizens of a number of other Western nations,[300] the nation's aviation sector is handling a significantly increased number of travellers. The Euro 2012 football tournament, held in Poland and Ukraine as joint hosts, prompted the government to invest heavily in transport infrastructure, and in particular airports.[301] The Donetsk airport, completed for Euro 2012, was destroyed by the end of 2014 because of the ongoing war between the government and the separatist movement.[302]

Kiev Boryspil is the county's largest international airport; it has three main passenger terminals and is the base for the country's flag carrier, Ukraine International Airlines. Other large airports in the country include those in Kharkiv, Lviv and Donetsk (now destroyed), whilst those in Dnipro and Odessa have plans for terminal upgrades in the near future. In addition to its flag carrier, Ukraine has a number of airlines including Windrose Airlines, Dniproavia, Azur Air Ukraine, and AtlasGlobal Ukraine. Antonov Airlines, a subsidiary of the Antonov Aerospace Design Bureau is the only operator of the world's largest fixed wing aircraft, the An-225.

International maritime travel is mainly provided through the Port of Odessa, from where ferries sail regularly to Istanbul, Varna and Haifa. The largest ferry company presently operating these routes is Ukrferry.[303]

Energy

In 2014, Ukraine was ranked number 19 on the Emerging Market Energy Security Growth Prosperity Index, published by the think tank Bisignis Institute, which ranks emerging market countries using government corruption, GDP growth and oil reserve information.[304]

Ukraine produces and processes its own natural gas and petroleum. However, the majority of these commodities are imported. Eighty percent of Ukrainian natural gas supplies are imported, mainly from Russia.[305]

Natural gas is heavily utilised not only in energy production but also by steel and chemical industries of the country, as well as by the district heating sector. In 2012, Shell started exploration drilling for shale gas in Ukraine—a project aimed at the nation's total gas supply independence. Following the armed conflict in the Donbass, Ukraine was cut off from half of coal and all of its anthracite extraction, dropping Ukrainian coal production by 22 percent in 2014. Russia was Ukraine's largest coal supplier, and in 2014 Russia blocked its coal supplies, forcing 22 Ukrainian power plants to shut down temporarily.

Power generation

Ukraine has been a net energy exporting country, for example in 2011, 3.3% of electricity produced were exported,[306] but also one of Europe's largest energy consumers.[307] As of 2011, 47.6% of total electricity generation was from nuclear power[306] The largest nuclear power plant in Europe, the Zaporizhia Nuclear Power Plant, is located in Ukraine. Until the 2010s, all of Ukraine's nuclear fuel was coming from Russia. In 2008 Westinghouse Electric Company won a five-year contract selling nuclear fuel to three Ukrainian reactors starting in 2011.[308] Following Euromaidan then President Viktor Yanukovych introduced a ban on Rosatom nuclear fuel shipments to Europe via Ukraine, which was in effect from 28 January until 6 March 2014.[309] By 2016, Russia's share was down to 55 percent, Westinghouse supplying nuclear fuel for six of Ukraine's VVER-1000 nuclear reactors.[310] After the Russian annexation of Crimea in April 2014, the National Nuclear Energy Generating Company of Ukraine Energoatom and Westinghouse extended the contract for fuel deliveries through 2020.[311]

Coal and gas-fired thermal power stations and hydroelectricity are the second and third largest kinds of power generation in the country.

Renewable energy use