Moldavian Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic

The Moldavian Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic (Moldovan: Република Аутономэ Советикэ Cочиалистэ Молдовеняскэ, Romanian: Republica Autonomă Sovietică Socialistă Moldovenească), shortened to Moldavian ASSR, was an autonomous republic of the Ukrainian SSR between 12 October 1924 and 2 August 1940, encompassing as well the modern territory of Transnistria (today "de jure" in Moldova, but "de facto" an independent state; see political status of Transnistria). It was an artificial political creation inspired by the Bolshevik nationalities policy in the context of the loss of larger Bessarabia to Romania in April 1918. In such a manner, the Bolshevik leadership tried to radicalize pro-Soviet feelings in Bessarabia with a goal to return it in the presence of favorable conditions and creation of geopolitical "place d'armes" (bridgehead) to execute a breakthrough in the Balkan direction by projecting influence upon Romanian Bessarabia, which would eventually be occupied in 1940 after the signing of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact.

| Moldavian Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Autonomous republic of the Ukrainian SSR | |||||||||

| 1924–1940 | |||||||||

.png) Coat of arms

| |||||||||

.svg.png) | |||||||||

| Capital | |||||||||

| Area | |||||||||

• 1940 | 7,516 km2 (2,902 sq mi) | ||||||||

| Population | |||||||||

• 1940 | 572339 | ||||||||

| Government | |||||||||

| • Type | Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic | ||||||||

| • Motto |

| ||||||||

| First Secretary | |||||||||

• 1924–1928 | Iosif Badeev | ||||||||

• 1939–1940 | Piotr Borodin | ||||||||

| History | |||||||||

• Established | 12 October 1924 | ||||||||

• Disestablished | 2 August 1940 | ||||||||

| Political subdivisions | Ribnitsa raion Dubossari raion Tiraspol raion Ananyiv raion | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||

Creation

The active propagandist of idea in creation of Moldavian autonomy on territory of Ukrainian Transnistria was Russian revolutionary and a native of Bessarabia Grigory Kotovsky (a member of the All-Russian Central Executive Committee).[1] In February 1924, a memorandum directed to the Central Committee of the Russian Communist Party (Bolshevik) and the Central Committee of the Communist Party (Bolshevik) of Ukraine and signed by Grigory Kotovsky, Bădulescu Alexandru, Pavel Tcacenco, Solomon Tinkelman (Timov), Alexandru Nicolau, Alter Zalic, Ion Dic Dicescu (also known as Isidor Cantor), Theodor Diamandescu, Teodor Chioran, and Vladimir Popovici, all signatories being Bolshevik activists (several of them from Bucharest).[1] The memorandum emphasized on the fact that on the left bank of Dniester compactly live from 500,000 to 800,000 Moldavians and that creation of Moldavian republic would play a role of powerful political and propaganda factor in solving the "Bessarabian question".[1]

Establishing the republic became a matter of dispute. Despite the objections of Soviet commissar of foreign relations Chicherin who argued that the new establishment would only strengthen the position of Romanians towards Bessarabia and able to activate "expansionist claims of Romanian chauvinism", Kremlin launched a campaign to create the autonomy attracting to it Bessarabian refugees and Romanian political emigrants who lived in Moscow and the Ukrainian Socialist Soviet Republic.[1]

On the other hand, Kotovski held that a new republic would spread Communist ideas into neighboring Bessarabia, with a chance that even Romania and the entire Balkan region would be revolutionized. For the Soviets the republic was to be a way for winning over Bessarabians of Romania and the first step towards a revolution in Romania.[2] This purpose is explained in an article of the newspaper Odessa Izvestia in 1924, in which a Russian politician, Vadeev says that "all the oppressed Moldavians from Bessarabia look at the future Republic like at a lighthouse, which spreads the light of freedom and human dignity,"[3] as well as in a book published in Moscow, which claimed that "once the economic and cultural growth of Moldavia has begun, aristocracy-led Romania will not be able to maintain its hold on Bessarabia."[4] While the creation of ethnic-based autonomous republics was a general Soviet policy at that time, with the creation of the Moldavian ASSR, the Soviet Union also hoped to bolster its claim to Bessarabia.[5]

On March 7, 1924, the Politburo of the Central Committee of the Communist Party (b) of Ukraine recognized a political prudence in creation of autonomy, yet to the final untangling of the question it was decided to return after a careful ascertainment of situation in the region.[1] The debated question was about a form in meeting the interests of Moldovan population (autonomous republic, autonomous oblast, district, or raion).[1] Whereas in process of carried work it became clear that statistical data on the number of Moldovans presented by the Kotovsky's commission is inflated compared to official, on 18 April 1924 the Politburo of the Central Committee of the Communist Party (b) of Ukraine approved to consider creation of the autonomy inappropriate.[1] However, in Moscow this position was ignored.[1] The All-Ukrainian Central Executive Committee (VUTsVK) yet went further and about a week later on 24 April 1924 it created the VUTsVK Central Commission on affairs of national minorities.[6]

Accepted on 29 July, the decision of the Central Committee of the Russian Communist Party (Bolshevik) contained categorical indication for the Central Committee of the Communist Party (b) of Ukraine on allocation of the Moldovan population into a special Autonomous republic as part of the Ukrainian Socialist Soviet Republic and obligated it to report already after a month about the course of the relevant work.[1] The decision about creation of the Autonomous Moldavian Socialist Soviet Republic was accepted by the 8th convocation of the All-Ukrainian Central Executive Committee at its 3rd session on 12 October 1924.[1]

Geography

The Moldavian ASSR was created from a territory previously administered as parts of the Odessa and Podolian Governorates of Ukraine. It accounted for 2% of the land and population of the Ukrainian SSR at the time.[7]

Initially (March 1924) organized as an oblast (Moldavian Autonomous Oblast), it had only four districts, all of them having a Moldavian majority:[8]

- Rîbnița – 48,748 inhabitants, of which 25,387 Moldavians – 52%

- Dubăsari – 57,371 inhabitants, of which 33,600 Moldavians- 58%

- Tiraspol – almost entirely Moldavians

- Ananyiv – 45,545 inhabitants, of which 24,249 Moldavians- 53%

On 12 October 1924, the oblast was elevated to the status of an autonomous republic and included several other territories, including some with little Moldavian population, such as the Balta district (where the capital was located), which had only 2.52% Moldavians.

The official capital was proclaimed the "temporarily occupied city of Kishinev". Meanwhile, a provisional capital was established in Balta and moved to Tiraspol in 1929, where it remained until part of the MASSR was integrated into the newly created Moldavian SSR, in 1940.[9]

History

The Moldavian Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic was established inside the Ukrainian SSR, on 12 October 1924.[7]

The area was quickly industrialized, and because of the lack of a qualified workforce, a significant migration from other Soviet republics occurred, predominantly Ukrainians and Russians. In particular, in 1928, of 14,300 industrial workers only about 600 were Moldavians.

In 1925, the MASSR survived a famine.

In December 1927, Time reported a number of anti-Soviet uprisings among peasants and factory workers in Tiraspol and other cities (Mogilev-Podolskiy, Kamyanets-Podolskiy) of southern Ukrainian SSR. Troops from Moscow were sent to the region and suppressed the unrest, resulting in ca 4000 deaths. The insurrections were at the time completely denied by the official Kremlin press.[10]

Collectivization in the MASSR was even more fast-paced than in Ukraine and was reported to be complete by summer 1931. This was accompanied by the deportation of about 2,000 families to Kazakhstan.

In 1932–33 another famine, known as Holodomor in Ukraine, occurred, with tens of thousands of peasants dying of starvation. During the famine, thousands of inhabitants tried to escape over the Dniester, despite the threat of being shot.[11] The most notable such incident happened near the village Olănești on February 23, 1932, when 40 persons were shot. This was reported in European newspapers by survivors. The Soviet side reported this as an escape of "kulak elements subverted by Romanian propaganda."

On 30 October 1930, from an improvised studio in Tiraspol, started broadcasting in Romanian language a Soviet radio of 4 kW whose main purpose was the anti-Romanian propaganda to Bessarabia between Prut and Dniester.[12] In the context in which a new radio mast, M. Gorky, built in 1936 in Tiraspol, allowed a greater coverage of the territory of Moldova, the Romanian state broadcaster started in 1937 to build Radio Basarabia, to counter Soviet propaganda.[13]

Demographics

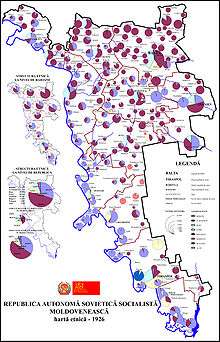

Moldavian ASSR had a mixed population, in which less than one third was Moldavian.[2] Its area was 7,516 km2 (2,902 sq mi) and included 11 raions on the left bank of Dniester.[7]

According to the 1926 Soviet census, the Republic had a population of 572,339,[14] of which:

| Ethnic group |

census 1926 | 1936 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | % | Number | % | |

| Ukrainians | 277,515 | 48.5% | 265,193 | 45.5% |

| Moldavians | 172,419 | 30.1% | 184,046 | 31.6% |

| Russians | 48,868 | 8.5% | 56,592 | 9.7% |

| Jews | 48,564 | 8.5% | 45,620 | 7.8% |

| Germans | 10,739 | 1.9% | 12,711 | 2.2% |

| Bulgarians | 6,026 | 1.1% | ||

| Poles | 4,853 | 0.8% | ||

| Romani | 918 | 0.2% | ||

| Romanians | 137 | 0.0% | ||

| Other | 2,300 | 0.4% | 13,526 | 2.4% |

| Total | 572,339 | 582,138 | ||

Despite this extensive territory allotted to the Moldavian Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic, about 85,000 Moldavians remained in Ukraine outside the territory of MASSR.[2]

Promotion of Moldavian identity

The tenet that the Moldavian language is distinct from the Romanian language was heavily promoted in the republic. Modern linguists generally agree that there is little difference between the two, mainly in accent and vocabulary. The republic also promoted irredentism towards Romania, proclaiming that the Moldavians in Bessarabia were "oppressed by Romanian imperialists".

As part of the effort to keep the language in Soviet Moldavia ("Moldavian Socialist culture") far from Romanian influences ("Romanian bourgeois culture"), a reformed Cyrillic script was used to write the language, in contrast with the Latin script officially used in Romania. The linguist Leonid Madan was assigned the task of establishing a literary standard, based on the Moldavian dialects of Transnistria and Bessarabia, as well as Russian loanwords or Russian-based calque.

In 1932, when in the entire Soviet Union there was a trend to move all languages to the Latin script, the Latin script and literary Romanian language was introduced in Moldavian schools and public use. Madan's books were removed from libraries and destroyed. This movement, however, was short lived, and in the second half of the 1940s a new trend of moving languages to the Cyrillic script started in the Soviet Union.

In 1937, during the Soviet Great Purge, many intellectuals in the Moldavian ASSR, accused of being enemies of the people, bourgeois nationalist or Trotskyist, were removed from their positions and repressed, with a large number of them executed. In 1938 the Cyrillic script was again declared official for the Moldavian language and the Latin script was banned. However, the literary language did not fully return to Madan's creation and remained closer to Romanian. After 1956, Madan's influences were entirely dropped from school books.

This policy remained in effect until 1989. Use of Cyrillic is still enforced in Moldova's breakaway region of Transnistria, where it is claimed to be returning the language to its roots.

| Administrative divisions of the Ukrainian SSR |

|---|

| First level |

|

|

| Second level |

|

| Third level |

|

|

|

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Moldova |

|

|

Early Middle Ages |

|

|

|

|

|

Disbanding

On June 26, 1940 the Soviet government issued an ultimatum to the Romanian minister in Moscow, demanding Romania to immediately cede Bessarabia and Northern Bukovina.[15] Italy and Germany, which needed a stable Romania and access to its oil fields urged King Carol II to comply. Under duress, with no prospect of aid from France or Britain, Romania ceded those territories.[16][17][18] On June 28, Soviet troops crossed the Dniester and occupied Bessarabia, Northern Bukovina, and the Hertza region. Territories where ethnic Ukrainians were the largest ethnic group (parts of Northern Bukovina and parts of Hotin, Cetatea Albă, and Izmail), as well as some adjoining regions with a Romanian majority, such as the Hertza region, were annexed to the Ukrainian SSR. The transfer of Bessarabia's Black Sea and Danube frontage to Ukraine ensured its control by a stable Soviet republic.

On August 2, 1940, the Soviet Union established the Moldavian Soviet Socialist Republic (Moldavian SSR), which consisted of six counties of Bessarabia joined with the westernmost part of what had been the MASSR,[15] effectively dissolving it.

Head of Government

- Revkom

- October 1924 – April 1925 Griogriy Stary (also Borisov)

- Soviet People's Commissars

- April 25, 1925 – May 1926 Aleksey Stroyev

- May 1926 – 1928 Griogriy Stary

- 1928 – April 1932 Sergei Dmitriu

- April 1932 – June 1937 Griogriy Stary (arrested June 22, 1937)

- July 1938 – ? Fyodor Brovko

- February 1939 Georgiy Streshny

Chairmen of Council

- Central Executive Committee

- April 25, 1925 – May 1926 Griogriy Stary

- May 1926 – May 1937 Yevstafiy Voronovich (shot in 1937)

- May 1937 – July 1938 Georgiy Streshny (acting)

- Supreme Council

- July 1938 – 1940 Tikhon Konstantinov

See also

- Moldavia Regional Committee of the Communist Party of Ukraine

- Grigore Kotovski

- Ecaterina Arbore

- Commission for the Study of the Communist Dictatorship in Moldova

- Transnistria Governorate

- Soviet occupation of Bessarabia and Northern Bukovina

- Karelian Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic - an ASSR with similar purpose on the Soviet-Finnish frontier

Notes

- Vermenych, Ya. Moldavian ASSR (МОЛДАВСЬКА АРСР). Encyclopedia of History of Ukraine.

- King, p.54

- Nistor, Vechimea... p.22, who cites Odessa Izvestia, 9 September 1924, no. 1429

- King, p.54, who cites Bochacher, Moldaviia, Gosizdat, Moscow, 1926

- Sidney & Beatrice Webb. Soviet Communism: A New Civilisation? Vol. I. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. 1936. p. 77. "This exclusively agricultural community... may perhaps be regarded as a lasting embodiment of the protest of the USSR against the Roumanian seizure of Bessarabia, which, it is hoped, may one day be enabled, as South Moldavia, to unite with the northern half of what is claimed to be a single community. With this view, the Moldavian Republic maintains a sovnarkom of People's Commissars, but is for many purposes dealt with as if it were merely an oblast of the Ukraine."

- Yakubova, L. VUTsVK Central Commission on affairs of national minorities (ЦЕНТРАЛЬНА КОМІСІЯ У СПРАВАХ НАЦІОНАЛЬНИХ МЕНШИН ПРИ ВУЦВК). Encyclopedia of History of Ukraine. 2013

- King, p.52

- Nistor, Vechimea... p.19, who cites Izvestia, 29 August 1924

- King, p. 55

- Disorder in the Ukraine?, Time, December 12, 1927

- King, p. 51

- Rodica Mahu, Radio Moldova se revendica de la Radio Tiraspol

- Radiofonie românească: Radio Basarabia

- Nistor, Vechimea... p.4; King, p. 54

- Charles King, The Moldovans: Romania, Russia, and the politics of culture, Hoover Institution Press, Stanford University, 2000. ISBN 0-8179-9792-X.

- Moshe Y. Sachs, Worldmark Encyclopedia of the Nations, John Wiley & Sons, 1988, ISBN 0-471-62406-3, p. 231

- William Julian Lewis , The Warsaw Pact: Arms, Doctrine, and Strategy, Institute for Foreign Policy Analysis, 1982, p.209

- Karel C Wellens, Eric Suy, International Law: Essays in Honour of Eric Suy, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, 1998, ISBN 90-411-0582-4, p. 79

References

- Charles King, The Moldovans: Romania, Russia, and the Politics of Culture, Hoover Institution Press, 2000

- (in Romanian) Elena Negru – Politica etnoculturală în RASS Moldovenească(Ethnocultural policy in Moldavian ASSR), Prut International publishing house, Chişinău 2003

- (in Romanian) Ion Nistor, Vechimea așezărilor românești dincolo de Nistru, București: Monitorul Oficial și Imprimeriile Statului, Imprimeria Națională, 1939

Further reading

- King, Charles (March 1998). "Ethnicity and institutional reform: The dynamics of "indigenization" in the Moldovan ASSR". Nationalities Papers. 26 (1): 57–72. doi:10.1080/00905999808408550.

.svg.png)