Hyperinflation

In economics, hyperinflation is very high and typically accelerating inflation. It quickly erodes the real value of the local currency, as the prices of all goods increase. This causes people to minimize their holdings in that currency as they usually switch to more stable foreign currencies, in recent history often the US dollar.[1] Prices typically remain stable in terms of other relatively stable currencies.

| Part of a series on |

| Economics |

|---|

|

|

|

By application |

|

Notable economists |

|

Lists |

|

Glossary |

|

Unlike low inflation, where the process of rising prices is protracted and not generally noticeable except by studying past market prices, hyperinflation sees a rapid and continuing increase in nominal prices, the nominal cost of goods, and in the supply of currency.[2] Typically, however, the general price level rises even more rapidly than the money supply as people try ridding themselves of the devaluing currency as quickly as possible. As this happens, the real stock of money (i.e., the amount of circulating money divided by the price level) decreases considerably.[3]

Hyperinflation is often associated with some stress to the government budget, such as wars or their aftermath, sociopolitical upheavals, a collapse in aggregate supply or one in export prices, or other crises that make it difficult for the government to collect tax revenue. A sharp decrease in real tax revenue coupled with a strong need to maintain government spending, together with an inability or unwillingness to borrow, can lead a country into hyperinflation.[3]

Definition

In 1956, Phillip Cagan wrote The Monetary Dynamics of Hyperinflation, the book often regarded as the first serious study of hyperinflation and its effects[4] (though The Economics of Inflation by C. Bresciani-Turroni on the German hyperinflation was published in Italian in 1931[5]). In his book, Cagan defined a hyperinflationary episode as starting in the month that the monthly inflation rate exceeds 50%, and as ending when the monthly inflation rate drops below 50% and stays that way for at least a year.[6] Economists usually follow Cagan's description that hyperinflation occurs when the monthly inflation rate exceeds 50% (this is equivalent to a yearly rate of 12,874.63%).[4]

The International Accounting Standards Board has issued guidance on accounting rules in a hyperinflationary environment. It does not establish an absolute rule on when hyperinflation arises. Instead, it lists factors that indicate the existence of hyperinflation:[7]

- The general population prefers to keep its wealth in non-monetary assets or in a relatively stable foreign currency. Amounts of local currency held are immediately invested to maintain purchasing power

- The general population regards monetary amounts not in terms of the local currency but in terms of a relatively stable foreign currency. Prices may be quoted in that currency;

- Sales and purchases on credit take place at prices that compensate for the expected loss of purchasing power during the credit period, even if the period is short;

- Interest rates, wages, and prices are linked to a price index; and

- The cumulative inflation rate over three years approaches, or exceeds, 100%.

Causes

While there can be a number of causes of high inflation, most hyperinflations have been caused by government budget deficits financed by currency creation. Peter Bernholz analysed 29 hyperinflations (following Cagan's definition) and concludes that at least 25 of them have been caused in this way.[8] A necessary condition for hyperinflation is the use of paper money, instead of gold or silver coins. Most hyperinflations in history, with some exceptions, such as the French hyperinflation of 1789–1796, occurred after the use of fiat currency became widespread in the late 19th century. The French hyperinflation took place after the introduction of a non-convertible paper currency, the assignats.

Money supply

Hyperinflation occurs when there is a continuing (and often accelerating) rapid increase in the amount of money that is not supported by a corresponding growth in the output of goods and services.

The increases in price that result from the rapid money creation creates a vicious circle, requiring ever growing amounts of new money creation to fund government deficits. Hence both monetary inflation and price inflation proceed at a rapid pace. Such rapidly increasing prices cause widespread unwillingness of the local population to hold the local currency as it rapidly loses its buying power. Instead they quickly spend any money they receive, which increases the velocity of money flow; this in turn causes further acceleration in prices. This means that the increase in the price level is greater than that of the money supply.[9] The real stock of money, M/P, decreases. Here M refers to the money stock and P to the price level.

This results in an imbalance between the supply and demand for the money (including currency and bank deposits), causing rapid inflation. Very high inflation rates can result in a loss of confidence in the currency, similar to a bank run. Usually, the excessive money supply growth results from the government being either unable or unwilling to fully finance the government budget through taxation or borrowing, and instead it finances the government budget deficit through the printing of money.[10]

Governments have sometimes resorted to excessively loose monetary policy, as it allows a government to devalue its debts and reduce (or avoid) a tax increase. Monetary inflation is effectively a flat tax on creditors that also redistributes proportionally to private debtors. Distributional effects of monetary inflation are complex and vary based on the situation, with some models finding regressive effects[11] but other empirical studies progressive effects.[12] As a form of tax, it is less overt than levied taxes and is therefore harder to understand by ordinary citizens. Inflation can obscure quantitative assessments of the true cost of living, as published price indices only look at data in retrospect, so may increase only months later. Monetary inflation can become hyperinflation if monetary authorities fail to fund increasing government expenses from taxes, government debt, cost cutting, or by other means, because either

- during the time between recording or levying taxable transactions and collecting the taxes due, the value of the taxes collected falls in real value to a small fraction of the original taxes receivable; or

- government debt issues fail to find buyers except at very deep discounts; or

- a combination of the above.

Theories of hyperinflation generally look for a relationship between seigniorage and the inflation tax. In both Cagan's model and the neo-classical models, a tipping point occurs when the increase in money supply or the drop in the monetary base makes it impossible for a government to improve its financial position. Thus when fiat money is printed, government obligations that are not denominated in money increase in cost by more than the value of the money created.

From this, it might be wondered why any rational government would engage in actions that cause or continue hyperinflation. One reason for such actions is that often the alternative to hyperinflation is either depression or military defeat. The root cause is a matter of more dispute. In both classical economics and monetarism, it is always the result of the monetary authority irresponsibly borrowing money to pay all its expenses. These models focus on the unrestrained seigniorage of the monetary authority, and the gains from the inflation tax.

In neo-classical economic theory, hyperinflation is rooted in a deterioration of the monetary base, that is the confidence that there is a store of value that the currency will be able to command later. In this model, the perceived risk of holding currency rises dramatically, and sellers demand increasingly high premiums to accept the currency. This in turn leads to a greater fear that the currency will collapse, causing even higher premiums. One example of this is during periods of warfare, civil war, or intense internal conflict of other kinds: governments need to do whatever is necessary to continue fighting, since the alternative is defeat. Expenses cannot be cut significantly since the main outlay is armaments. Further, a civil war may make it difficult to raise taxes or to collect existing taxes. While in peacetime the deficit is financed by selling bonds, during a war it is typically difficult and expensive to borrow, especially if the war is going poorly for the government in question. The banking authorities, whether central or not, "monetize" the deficit, printing money to pay for the government's efforts to survive. The hyperinflation under the Chinese Nationalists from 1939 to 1945 is a classic example of a government printing money to pay civil war costs. By the end, currency was flown in over the Himalayas, and then old currency was flown out to be destroyed.

Hyperinflation is a complex phenomenon and one explanation may not be applicable to all cases. In both of these models, however, whether loss of confidence comes first, or central bank seigniorage, the other phase is ignited. In the case of rapid expansion of the money supply, prices rise rapidly in response to the increased supply of money relative to the supply of goods and services, and in the case of loss of confidence, the monetary authority responds to the risk premiums it has to pay by "running the printing presses."

Nevertheless, the immense acceleration process that occurs during hyperinflation (such as during the German hyperinflation of 1922/23) still remains unclear and unpredictable. The transformation of an inflationary development into the hyperinflation has to be identified as a very complex phenomenon, which could be a further advanced research avenue of the complexity economics in conjunction with research areas like mass hysteria, bandwagon effect, social brain, and mirror neurons.[13]

Supply shocks

A number of hyperinflations were caused by some sort of extreme negative supply shock, often but not always associated with wars, the breakdown of the communist system or natural disasters.[14]

Models

Since hyperinflation is visible as a monetary effect, models of hyperinflation center on the demand for money. Economists see both a rapid increase in the money supply and an increase in the velocity of money if the (monetary) inflating is not stopped. Either one, or both of these together are the root causes of inflation and hyperinflation. A dramatic increase in the velocity of money as the cause of hyperinflation is central to the "crisis of confidence" model of hyperinflation, where the risk premium that sellers demand for the paper currency over the nominal value grows rapidly. The second theory is that there is first a radical increase in the amount of circulating medium, which can be called the "monetary model" of hyperinflation. In either model, the second effect then follows from the first—either too little confidence forcing an increase in the money supply, or too much money destroying confidence.

In the confidence model, some event, or series of events, such as defeats in battle, or a run on stocks of the specie that back a currency, removes the belief that the authority issuing the money will remain solvent—whether a bank or a government. Because people do not want to hold notes that may become valueless, they want to spend them. Sellers, realizing that there is a higher risk for the currency, demand a greater and greater premium over the original value. Under this model, the method of ending hyperinflation is to change the backing of the currency, often by issuing a completely new one. War is one commonly cited cause of crisis of confidence, particularly losing in a war, as occurred during Napoleonic Vienna, and capital flight, sometimes because of "contagion" is another. In this view, the increase in the circulating medium is the result of the government attempting to buy time without coming to terms with the root cause of the lack of confidence itself.

In the monetary model, hyperinflation is a positive feedback cycle of rapid monetary expansion. It has the same cause as all other inflation: money-issuing bodies, central or otherwise, produce currency to pay spiraling costs, often from lax fiscal policy, or the mounting costs of warfare. When business people perceive that the issuer is committed to a policy of rapid currency expansion, they mark up prices to cover the expected decay in the currency's value. The issuer must then accelerate its expansion to cover these prices, which pushes the currency value down even faster than before. According to this model the issuer cannot "win" and the only solution is to abruptly stop expanding the currency. Unfortunately, the end of expansion can cause a severe financial shock to those using the currency as expectations are suddenly adjusted. This policy, combined with reductions of pensions, wages, and government outlays, formed part of the Washington consensus of the 1990s.

Whatever the cause, hyperinflation involves both the supply and velocity of money. Which comes first is a matter of debate, and there may be no universal story that applies to all cases. But once the hyperinflation is established, the pattern of increasing the money stock, by whichever agencies are allowed to do so, is universal. Because this practice increases the supply of currency without any matching increase in demand for it, the price of the currency, that is the exchange rate, naturally falls relative to other currencies. Inflation becomes hyperinflation when the increase in money supply turns specific areas of pricing power into a general frenzy of spending quickly before money becomes worthless. The purchasing power of the currency drops so rapidly that holding cash for even a day is an unacceptable loss of purchasing power. As a result, no one holds currency, which increases the velocity of money, and worsens the crisis.

Because rapidly rising prices undermine the role of money as a store of value, people try to spend it on real goods or services as quickly as possible. Thus, the monetary model predicts that the velocity of money will increase as a result of an excessive increase in the money supply. At the point when money velocity and prices rapidly accelerate in a vicious circle, hyperinflation is out of control, because ordinary policy mechanisms, such as increasing reserve requirements, raising interest rates, or cutting government spending will be ineffective and be responded to by shifting away from the rapidly devalued money and towards other means of exchange.

During a period of hyperinflation, bank runs, loans for 24-hour periods, switching to alternate currencies, the return to use of gold or silver or even barter become common. Many of the people who hoard gold today expect hyperinflation, and are hedging against it by holding specie. There may also be extensive capital flight or flight to a "hard" currency such as the US dollar. This is sometimes met with capital controls, an idea that has swung from standard, to anathema, and back into semi-respectability. All of this constitutes an economy that is operating in an "abnormal" way, which may lead to decreases in real production. If so, that intensifies the hyperinflation, since it means that the amount of goods in "too much money chasing too few goods" formulation is also reduced. This is also part of the vicious circle of hyperinflation.

Once the vicious circle of hyperinflation has been ignited, dramatic policy means are almost always required. Simply raising interest rates is insufficient. Bolivia, for example, underwent a period of hyperinflation in 1985, where prices increased 12,000% in the space of less than a year. The government raised the price of gasoline, which it had been selling at a huge loss to quiet popular discontent, and the hyperinflation came to a halt almost immediately, since it was able to bring in hard currency by selling its oil abroad. The crisis of confidence ended, and people returned deposits to banks. The German hyperinflation (1919 – November 1923) was ended by producing a currency based on assets loaned against by banks, called the Rentenmark. Hyperinflation often ends when a civil conflict ends with one side winning.

Although wage and price controls are sometimes used to control or prevent inflation, no episode of hyperinflation has been ended by the use of price controls alone, because price controls that force merchants to sell at prices far below their restocking costs result in shortages that cause prices to rise still further.

Nobel prize winner Milton Friedman said "We economists don't know much, but we do know how to create a shortage. If you want to create a shortage of tomatoes, for example, just pass a law that retailers can't sell tomatoes for more than two cents per pound. Instantly you'll have a tomato shortage. It's the same with oil or gas."[15]

Effects

Hyperinflation increases stock market prices; effectively wipes out the purchasing power of private and public savings; distorts the economy in favor of the hoarding of real assets; causes the monetary base, whether specie or hard currency, to flee the country; and makes the afflicted area anathema to investment.

One of the most important characteristics of hyperinflation is the accelerating substitution of the inflating money by stable money—gold and silver in former times, then relatively stable foreign currencies after the breakdown of the gold or silver standards (Thiers' Law). If inflation is high enough, government regulations like heavy penalties and fines, often combined with exchange controls, cannot prevent this currency substitution. As a consequence, the inflating currency is usually heavily undervalued compared to stable foreign money in terms of purchasing power parity. So foreigners can live cheaply and buy at low prices in the countries hit by high inflation. It follows that governments that do not succeed in engineering a successful currency reform in time must finally legalize the stable foreign currencies (or, formerly, gold and silver) that threaten to fully substitute the inflating money. Otherwise, their tax revenues, including the inflation tax, will approach zero.[16] The last episode of hyperinflation in which this process could be observed was in Zimbabwe in the first decade of the 21st century. In this case, the local money was mainly driven out by the US dollar and the South African rand.

Enactment of price controls to prevent discounting the value of paper money relative to gold, silver, hard currency, or other commodities fail to force acceptance of a paper money that lacks intrinsic value. If the entity responsible for printing a currency promotes excessive money printing, with other factors contributing a reinforcing effect, hyperinflation usually continues. Hyperinflation is generally associated with paper money, which can easily be used to increase the money supply: add more zeros to the plates and print, or even stamp old notes with new numbers.[17] Historically, there have been numerous episodes of hyperinflation in various countries followed by a return to "hard money". Older economies would revert to hard currency and barter when the circulating medium became excessively devalued, generally following a "run" on the store of value.

Much attention on hyperinflation centers on the effect on savers whose investments become worthless. Interest rate changes often cannot keep up with hyperinflation or even high inflation, certainly with contractually fixed interest rates. For example, in the 1970s in the United Kingdom inflation reached 25% per annum, yet interest rates did not rise above 15%—and then only briefly—and many fixed interest rate loans existed. Contractually, there is often no bar to a debtor clearing his long term debt with "hyperinflated cash", nor could a lender simply somehow suspend the loan. Contractual "early redemption penalties" were (and still are) often based on a penalty of n months of interest/payment; again no real bar to paying off what had been a large loan. In interwar Germany, for example, much private and corporate debt was effectively wiped out—certainly for those holding fixed interest rate loans.

Ludwig von Mises used the term "crack-up boom" (German: Katastrophenhausse) to describe the economic consequences of an unmitigated increasing in the base-money supply.[18] As more and more money is provided, interest rates decline towards zero. Realizing that fiat money is losing value, investors will try to place money in assets such as real estate, stocks, even art; as these appear to represent "real" value. Asset prices are thus becoming inflated. This potentially spiraling process will ultimately lead to the collapse of the monetary system. The Cantillon effect[19] says that those institutions that receive the new money first are the beneficiaries of the policy.

Aftermath

Hyperinflation is ended by drastic remedies, such as imposing the shock therapy of slashing government expenditures or altering the currency basis. One form this may take is dollarization, the use of a foreign currency (not necessarily the U.S. dollar) as a national unit of currency. An example was dollarization in Ecuador, initiated in September 2000 in response to a 75% loss of value of the Ecuadorian sucre in early 2000. But usually the "dollarization" takes place in spite of all efforts of the government to prevent it by exchange controls, heavy fines and penalties. The government has thus to try to engineer a successful currency reform stabilizing the value of the money. If it does not succeed with this reform the substitution of the inflating by stable money goes on. Thus it is not surprising that there have been at least seven historical cases in which the good (foreign) money did fully drive out the use of the inflating currency. In the end the government had to legalize the former, for otherwise its revenues would have fallen to zero.[16]

Hyperinflation has always been a traumatic experience for the people who suffer it, and the next political regime almost always enacts policies to try to prevent its recurrence. Often this means making the central bank very aggressive about maintaining price stability, as was the case with the German Bundesbank, or moving to some hard basis of currency, such as a currency board. Many governments have enacted extremely stiff wage and price controls in the wake of hyperinflation, but this does not prevent further inflation of the money supply by the central bank, and always leads to widespread shortages of consumer goods if the controls are rigidly enforced.

Currency

In countries experiencing hyperinflation, the central bank often prints money in larger and larger denominations as the smaller denomination notes become worthless. This can result in the production of unusually large denominations of banknotes, including those denominated in amounts of 1,000,000,000 or more.

- By late 1923, the Weimar Republic of Germany was issuing two-trillion mark banknotes and postage stamps with a face value of fifty billion marks. The highest value banknote issued by the Weimar government's Reichsbank had a face value of 100 trillion marks (1014; 100,000,000,000,000; 100 million million).[20][21] At the height of the inflation, one US dollar was worth 4 trillion German marks. One of the firms printing these notes submitted an invoice for the work to the Reichsbank for 32,776,899,763,734,490,417.05 (3.28 × 1019, roughly 33 quintillion) marks.[22]

- The largest denomination banknote ever officially issued for circulation was in 1946 by the Hungarian National Bank for the amount of 100 quintillion pengő (1020; 100,000,000,000,000,000,000; 100 million million million) image. (A banknote worth 10 times as much, 1021 (1 sextillion) pengő, was printed but not issued image.) The banknotes did not show the numbers in full: "hundred million b.-pengő" ("hundred million trillion pengő") and "one milliard b.-pengő" were spelled out instead. This makes the 100,000,000,000,000 Zimbabwean dollar banknotes the note with the greatest number of zeros shown.

- The Post-World War II hyperinflation of Hungary held the record for the most extreme monthly inflation rate ever – 41.9 quadrillion percent (4.19 × 1016%; 41,900,000,000,000,000%) for July 1946, amounting to prices doubling every 15.3 hours. By comparison, recent figures (as of 14 November 2008) estimate Zimbabwe's annual inflation rate at 89.7 sextillion (1021) percent.[23] The highest monthly inflation rate of that period was 79.6 billion percent (7.96 × 1010%; 79,600,000,000%), and a doubling time of 24.7 hours.

One way to avoid the use of large numbers is by declaring a new unit of currency. (As an example, instead of 10,000,000,000 dollars, a central bank might set 1 new dollar = 1,000,000,000 old dollars, so the new note would read "10 new dollars".) A recent example of this is Turkey's revaluation of the Lira on 1 January 2005, when the old Turkish lira (TRL) was converted to the New Turkish lira (TRY) at a rate of 1,000,000 old to 1 new Turkish Lira. While this does not lessen the actual value of a currency, it is called redenomination or revaluation and also occasionally happens in countries with lower inflation rates. During hyperinflation, currency inflation happens so quickly that bills reach large numbers before revaluation.

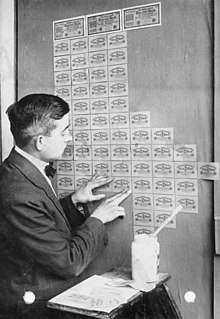

Some banknotes were stamped to indicate changes of denomination, as it would have taken too long to print new notes. By the time new notes were printed, they would be obsolete (that is, they would be of too low a denomination to be useful).

Metallic coins were rapid casualties of hyperinflation, as the scrap value of metal enormously exceeded its face value. Massive amounts of coinage were melted down, usually illicitly, and exported for hard currency.

Governments will often try to disguise the true rate of inflation through a variety of techniques. None of these actions addresses the root causes of inflation; and if discovered, they tend to further undermine trust in the currency, causing further increases in inflation. Price controls will generally result in shortages and hoarding and extremely high demand for the controlled goods, causing disruptions of supply chains. Products available to consumers may diminish or disappear as businesses no longer find it economic to continue producing and/or distributing such goods at the legal prices, further exacerbating the shortages.

There are also issues with computerized money-handling systems. In Zimbabwe, during the hyperinflation of the Zimbabwe dollar, many automated teller machines and payment card machines struggled with arithmetic overflow errors as customers required many billions and trillions of dollars at one time.[24]

Notable hyperinflationary episodes

Rome

During the Crisis of the Third Century, Rome underwent hyperinflation caused by years of coinage devaluation.[25]

Austria

In 1922, inflation in Austria reached 1,426%, and from 1914 to January 1923, the consumer price index rose by a factor of 11,836, with the highest banknote in denominations of 500,000 Austrian krones.[26][lower-alpha 1] After World War I, essentially all State enterprises ran at a loss, and the number of state employees in the capital, Vienna, was greater than in the earlier monarchy, even though the new republic was nearly one-eighth of the size.[28]

Observing the Austrian response to developing hyperinflation, which included the hoarding of food and the speculation in foreign currencies, Owen S. Phillpotts, the Commercial Secretary at the British Legation in Vienna wrote: "The Austrians are like men on a ship who cannot manage it, and are continually signalling for help. While waiting, however, most of them begin to cut rafts, each for himself, out of the sides and decks. The ship has not yet sunk despite the leaks so caused, and those who have acquired stores of wood in this way may use them to cook their food, while the more seamanlike look on cold and hungry. The population lack courage and energy as well as patriotism."[29]

- Start and end date: October 1921 – September 1922

- Peak month and rate of inflation: August 1922, 129%[30]

Bolivia

Increasing hyperinflation in Bolivia has plagued, and at times crippled, its economy and currency since the 1970s. At one time in 1985, the country experienced an annual inflation rate of more than 20,000%. Fiscal and monetary reform reduced the inflation rate to single digits by the 1990s, and in 2004 Bolivia experienced a manageable 4.9% rate of inflation.[31]

In 1987, the Bolivian peso was replaced by a new boliviano at a rate of one million to one (when 1 US dollar was worth 1.8–1.9 million pesos). At that time, 1 new boliviano was roughly equivalent to 1 U.S. dollar.

Brazil

Brazilian hyperinflation lasted from 1985 (the year when the military dictatorship ended) to 1994, with prices rising by 184,901,570,954.39% (or 1.849×1011 percent) in that time[32] due to the uncontrolled printing of money.[33] There were many economic plans that tried to contain hyperinflation including zeroes cuts, price freezes and even confiscation of bank accounts.[33][34]

The highest value was in March 1990, when the government inflation index reached 82.39%.[33][35] Hyperinflation ended in July 1994 with the Real Plan during the government of Itamar Franco.[36] During the period of inflation Brazil adopted a total of six different currencies, as the government constantly changed due to rapid devaluation and increase in the number of zeros.[36][33]

China

As the first user of fiat currency, China was also the first country to experience hyperinflation. Paper currency was introduced during the Tang Dynasty, and was generally welcomed. It maintained its value, as successive Chinese governments put in place strict controls on issuance. The convenience of paper currency for trade purposes led to strong demand for paper currency. It was only when discipline on quantity supplied broke down that hyperinflation emerged.[38] The Yuan Dynasty (1271–1368) was the first to print large amounts of fiat paper money to fund its wars, resulting in hyperinflation. Much later, the Republic of China went through hyperinflation from 1948 to 1949. In 1947, the highest denomination bill was 50,000 yuan. By mid-1948, the highest denomination was 180,000,000 yuan. The 1948 currency reform replaced the yuan by the gold yuan at an exchange rate of 1 gold yuan = 3,000,000 yuan. In less than a year, the highest denomination was 10,000,000 gold yuan. In the final days of the civil war, the silver yuan was briefly introduced at the rate of 500,000,000 gold yuan. Meanwhile, the highest denomination issued by a regional bank was 6,000,000,000 yuan (issued by Xinjiang Provincial Bank in 1949). After renminbi was instituted by the new communist government, hyperinflation ceased, with a revaluation of 1:10,000 old yuan in 1955.

- First episode:

- Start and end date: July 1943 – August 1945

- Peak month and rate of inflation: June 1945, 302%

- Second episode:

- Start and end date: October 1947 – mid May 1949

- Peak month and rate of inflation: April 5,070%[39]

France

During the French Revolution and first Republic, the National Assembly issued bonds, some backed by seized church property, called assignats.[40] Napoleon replaced them with the franc in 1803, at which time the assignats were basically worthless. Stephen D. Dillaye pointed out that one of the reasons for the failure was massive counterfeiting of the paper currency, largely through London. According to Dillaye: "Seventeen manufacturing establishments were in full operation in London, with a force of four hundred men devoted to the production of false and forged Assignats."[41]

- Start and end date: May 1795 – November 1796

- Peak month and rate of inflation: mid August 1796, 304%[42]

Germany (Weimar Republic)

By November 1922, the value in gold of money in circulation had fallen from £300 million before World War I to £20 million. The Reichsbank responded by the unlimited printing of notes, thereby accelerating the devaluation of the mark. In his report to London, Lord D'Abernon wrote: "In the whole course of history, no dog has ever run after its own tail with the speed of the Reichsbank."[43][44] Germany went through its worst inflation in 1923. In 1922, the highest denomination was 50,000 marks. By 1923, the highest denomination was 100,000,000,000,000 (1014) Marks. In December 1923 the exchange rate was 4,200,000,000,000 (4.2 × 1012) Marks to 1 US dollar.[45] In 1923, the rate of inflation hit 3.25 × 106 percent per month (prices double every two days). Beginning on 20 November 1923, 1,000,000,000,000 old Marks were exchanged for 1 Rentenmark, so that 4.2 Rentenmarks were worth 1 US dollar, exactly the same rate the Mark had in 1914.[45]

- First phase:

- Start and end date: January 1920 – January 1920

- Peak month and rate of inflation: January 1920, 56.9%

- Second phase:

- Start and end date: August 1922 – December 1923

- Peak month and rate of inflation: November 1923, 29,525%[30]

Greece (German–Italian occupation)

With the German invasion in April 1941, there was an abrupt increase in prices. This was due to psychological factors related to the fear of shortages and to the hoarding of goods. During the German and Italian Axis occupation of Greece (1941–1944), the agricultural, mineral, industrial etc. production of Greece were used to sustain the occupation forces, but also to secure provisions for the Afrika Korps. One part of these "sales" of provisions was settled with bilateral clearing through the German DEGRIGES and the Italian Sagic companies at very low prices. As the value of Greek exports in drachmas fell, the demand for drachmas followed suit and so did its forex rate. While shortages started due to naval blockades and hoarding, the prices of commodities soared. The other part of the "purchases" was settled with drachmas secured from the Bank of Greece and printed for this purpose by private printing presses. As prices soared, the Germans and Italians started requesting more and more drachmas from the Bank of Greece to offset price increases; each time prices increased, the note circulation followed suit soon afterwards. For the year starting November 1943, the inflation rate was 2.5 × 1010%, the circulation was 6.28 × 1018 drachmae and one gold sovereign cost 43,167 billion drachmas. The hyperinflation started subsiding immediately after the departure of the German occupation forces, but inflation rates took several years before they fell below 50%.[46]

- Start and end date: June 1941 – January 1946

- Peak month and rate of inflation: December 1944, 3.0×1010%

Hungary

The Treaty of Trianon and political instability between 1919 and 1924 led to a major inflation of Hungary's currency. In 1921, in an attempt to stop this inflation, the national assembly of Hungary passed the Hegedűs reforms, including a 20% levy on bank deposits, but this precipitated a mistrust of banks by the public, especially the peasants, and resulted in a reduction in savings, and thus an increase in the amount of currency in circulation.[47] Due to the reduced tax base, the government resorted to printing money, and in 1923 inflation in Hungary reached 98% per month.

Between the end of 1945 and July 1946, Hungary went through the highest inflation ever recorded. In 1944, the highest banknote value was 1,000 pengő. By the end of 1945, it was 10,000,000 pengő, and the highest value in mid-1946 was 100,000,000,000,000,000,000 (1020) pengő. A special currency, the adópengő (or tax pengő) was created for tax and postal payments.[48] The inflation was such that the value of the adópengő was adjusted each day by radio announcement. On 1 January 1946, one adópengő equaled one pengő, but by late July, one adópengő equaled 2,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 or 2×1021 (2 sextillion) pengő.

When the pengő was replaced in August 1946 by the forint, the total value of all Hungarian banknotes in circulation amounted to 1⁄1,000 of one US cent.[49] Inflation had peaked at 1.3 × 1016% per month (i.e. prices doubled every 15.6 hours).[50] On 18 August 1946, 400,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 or 4×1029 pengő (four hundred quadrilliard on the long scale used in Hungary, or four hundred octillion on short scale) became 1 forint.

- Start and end date: August 1945 – July 1946

- Peak month and rate of inflation: July 1946, 41.9×1015%[51]

North Korea

North Korea has most likely experienced hyperinflation from December 2009 to mid-January 2011. Based on the price of rice, North Korea's hyperinflation peaked in mid-January 2010, but according to black market exchange-rate data, and calculations based on purchasing power parity, North Korea experienced its peak month of inflation in early March 2010. These data points are unofficial, however, and therefore must be treated with a degree of caution.[52]

Peru

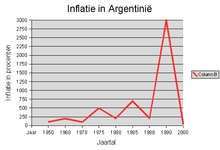

In modern history, Peru underwent a period of hyperinflation period in the 1980s to the early 1990s starting with President Fernando Belaúnde's second administration, heightened during Alan García's first administration, to the beginning of Alberto Fujimori's term. Over 3,210,000,000 old soles would be worth one USD. Garcia's term introduced the inti, which worsened inflation into hyperinflation. Peru's currency and economy were pacified under Fujimori's Nuevo Sol program, which has remained Peru's currency since 1991.[53]

Poland

Poland has gone through two episodes of hyperinflation since the country regained independence following the end of World War I, the first in 1923, the second in 1989–1990. Both events resulted in the introduction of new currencies. In 1924, the złoty replaced the original currency of post-war Poland, the mark. This currency was subsequently replaced by another of the same name in 1950, which was assigned the ISO code of PLZ. As a result of the second hyperinflation crisis, the current new złoty was introduced in 1990 (ISO code: PLN). See the article on Polish złoty for more information about the currency's history.

The newly independent Poland had been struggling with a large budget deficit since its inception in 1918 but it was in 1923 when inflation reached its peak. The exchange rate to the American dollar went from 9 Polish marks per dollar in 1918 to 6,375,000 marks per dollar at the end of 1923. A new personal 'inflation tax' was introduced. The resolution of the crisis is attributed to Władysław Grabski, who became prime minister of Poland in December 1923. Having nominated an all-new government and being granted extraordinary lawmaking powers by the Sejm for a period of six months, he introduced a new currency, established a new national bank and scrapped the inflation tax, which took place throughout 1924.[54]

The economic crisis in Poland in the 1980s was accompanied by rising inflation when new money was printed to cover a budget deficit. Although inflation was not as acute as in 1920s, it is estimated that its annual rate reached around 600% in a period of over a year spanning parts of 1989 and 1990. The economy was stabilised by the adoption of the Balcerowicz Plan in 1989, named after the main author of the reforms, minister of finance Leszek Balcerowicz. The plan was largely inspired by the previous Grabski's reforms.[54]

Philippines

The Japanese government occupying the Philippines during World War II issued fiat currencies for general circulation. The Japanese-sponsored Second Philippine Republic government led by Jose P. Laurel at the same time outlawed possession of other currencies, most especially "guerrilla money". The fiat money's lack of value earned it the derisive nickname "Mickey Mouse money". Survivors of the war often tell tales of bringing suitcases or bayong (native bags made of woven coconut or buri leaf strips) overflowing with Japanese-issued bills. Early on, 75 Mickey Mouse pesos could buy one duck egg.[55] In 1944, a box of matches cost more than 100 Mickey Mouse pesos.[56]

In 1942, the highest denomination available was 10 pesos. Before the end of the war, because of inflation, the Japanese government was forced to issue 100-, 500-, and 1000-peso notes.

- Start and end date: January 1944 – December 1944

- Peak month and rate of inflation: January 1944, 60%[57]

Japanese-occupied Malaya

.jpg)

Malaya and Singapore were under Japanese occupation from 1942 until 1945. The Japanese issued banana money as the official currency to replace the Straits currency issued by the British. During that time, the cost of basic necessities increased drastically. As the occupation proceeded, the Japanese authorities printed more money to fund their wartime activities, which resulted in hyperinflation and a severe depreciation in value of the banana note.

From February to December 1942, $100 of Straits currency was worth $100 in Japanese scrip, after which the value of Japanese scrip began to erode, reaching $385 on December 1943 and $1,850 one year later. By 1 August 1945, this had inflated to $10,500, and 11 days later it had reached $95,000. After 13 August 1945, Japanese scrip had become valueless.[58]

Soviet Union

A seven-year period of uncontrollable spiralling inflation occurred in the early Soviet Union, running from the earliest days of the Bolshevik Revolution in November 1917 to the reestablishment of the gold standard with the introduction of the chervonets as part of the New Economic Policy. The inflationary crisis effectively ended in March 1924 with the introduction of the so-called "gold ruble" as the country's standard currency.

The early Soviet hyperinflationary period was marked by three successive redenominations of its currency, in which "new rubles" replaced old at the rates of 10,000:1 (1 January 1922), 100:1 (1 January 1923), and 50,000:1 (7 March 1924), respectively.

Between 1921 and 1922, inflation in the Soviet Union reached 213%.

Venezuela

_on_a_logarithmic_scale.png)

Venezuela's hyperinflation began in November 2016.[59] Inflation of Venezuela's bolivar fuerte (VEF) in 2014 reached 69%[60] and was the highest in the world.[61][62] In 2015, inflation was 181%, the highest in the world and the highest in the country's history at that time,[63][64] 800% in 2016,[65] over 4,000% in 2017,[66][67][68][69] and 1,698,488% in 2018,[70] with Venezuela spiraling into hyperinflation.[71] While the Venezuelan government "has essentially stopped" producing official inflation estimates as of early 2018, one estimate of the rate at that time was 5,220%, according to inflation economist Steve Hanke of Johns Hopkins University.[72]

Inflation has affected Venezuelans so much that in 2017, some people became video game gold farmers and could be seen playing games such as RuneScape to sell in-game currency or characters for real currency. In many cases, these gamers made more money than salaried workers in Venezuela even though they were earning just a few dollars per day.[73] During the Christmas season of 2017, some shops would no longer use price tags since prices would inflate so quickly, so customers were required to ask staff at stores how much each item was.[74]

The International Monetary Fund estimated in 2018 that Venezuela's inflation rate would reach 1,000,000% by the end of the year.[75] This forecast was criticized by Steve H. Hanke, professor of applied economics at The Johns Hopkins University and senior fellow at the Cato Institute. According to Hanke, the IMF had released a "bogus forecast" because "no one has ever been able to accurately forecast the course or the duration of an episode of hyperinflation. But that has not stopped the IMF from offering inflation forecasts for Venezuela that have proven to be wildly inaccurate".[76]

In July 2018, hyperinflation in Venezuela was sitting at 33,151%, "the 23rd most severe episode of hyperinflation in history".[76]

In April 2019, the International Monetary Fund estimated that inflation would reach 10,000,000% by the end of 2019.[77]

In May 2019, the Central Bank of Venezuela released economic data for the first time since 2015. According to this release, the inflation of Venezuela was 274% in 2016, 863% in 2017 and 130,060% in 2018.[78] The annualised inflation rate as of April 2019 was estimated to be 282,972.8% as of April 2019, and cumulative inflation from 2016 to April 2019 was estimated at 53,798,500%.[79]

The new reports imply a contraction of more than half of the economy in five years, according to the Financial Times "one of the biggest contractions in Latin American history".[80] According two undisclosed sources from Reuters, the release of this numbers was due to pressure from China, a Maduro ally. One of this sources claims that the disclosure of economic numbers may bring Venezuela into compliance with the IMF, making it harder to support Juan Guaidó during the presidential crisis.[81] At the time, the IMF was not able to support the validity of the data as they had not been able to contact the authorities.[81]

- Start and end date: November 2016 – present

- Peak month and rate of inflation: April 2018, 234% (Hanke estimate);[82] September 2018, 233% (National Assembly estimate)[83]

Yugoslavia

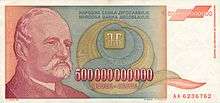

Yugoslavia went through a period of hyperinflation and subsequent currency reforms from 1989 to 1994. One of several regional conflicts accompanying the dissolution of Yugoslavia was the Bosnian War (1992–1995). The Belgrade government of Slobodan Milošević backed ethnic Serbian forces in the conflict, resulting in a United Nations boycott of Yugoslavia. The UN boycott collapsed an economy already weakened by regional war, with the projected monthly inflation rate accelerating to one million percent by December 1993 (prices double every 2.3 days).[84]

The highest denomination in 1988 was 50,000 dinars. By 1989 it was 2,000,000 dinars. In the 1990 currency reform, 1 new dinar was exchanged for 10,000 old dinars. In the 1992 currency reform, 1 new dinar was exchanged for 10 old dinars. The highest denomination in 1992 was 50,000 dinars. By 1993, it was 10,000,000,000 dinars. In the 1993 currency reform, 1 new dinar was exchanged for 1,000,000 old dinars. Before the year was over, however, the highest denomination was 500,000,000,000 dinars. In the 1994 currency reform, 1 new dinar was exchanged for 1,000,000,000 old dinars. In another currency reform a month later, 1 novi dinar was exchanged for 13 million dinars (1 novi dinar = 1 German mark at the time of exchange). The overall impact of hyperinflation was that 1 novi dinar was equal to 1 × 1027 – 1.3 × 1027 pre-1990 dinars. Yugoslavia's rate of inflation hit 5 × 1015% cumulative inflation over the time period 1 October 1993 and 24 January 1994.

- First episode:

- Start and End Date: Sept. 1989 – Dec. 1989

- Peak month and rate of inflation: December 1989, 59.7%

- Second episode:

- Start and end date: April 1992 – January 1994

- Peak month and rate of inflation: January 1994, 3.13×109%[85]

Zimbabwe

Hyperinflation in Zimbabwe was one of the few instances that resulted in the abandonment of the local currency. At independence in 1980, the Zimbabwe dollar (ZWD) was worth about US$1.25. Afterwards, however, rampant inflation and the collapse of the economy severely devalued the currency. Inflation was steady until British Prime Minister Tony Blair reneged on land reform agreements arrived at between Margaret Thatcher and Robert Mugabe that continued land redistribution from the white farming community in 1998, resulting in reductions in food production and the decline of foreign investment. Several multinational companies began hoarding retail goods in warehouses in Zimbabwe and just south of the border, preventing commodities from becoming available on the market.[86][87][88][89] The result was that to pay its expenditures Mugabe's government and Gideon Gono's Reserve Bank printed more and more notes with higher face values.

Hyperinflation began early in the 21st century, reaching 624% in 2004. It fell back to low triple digits before surging to a new high of 1,730% in 2006. The Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe revalued on 1 August 2006 at a ratio of 1,000 ZWD to each second dollar (ZWN), but year-to-year inflation rose by June 2007 to 11,000% (versus an earlier estimate of 9,000%). Larger denominations were progressively issued in 2008:

- 5 May: banknotes or "bearer cheques" for the value of ZWN 100 million and ZWN 250 million.[90]

- 15 May: new bearer cheques with a value of ZWN 500 million (then equivalent to about US$2.50).[91]

- 20 May: a new series of notes ("agro cheques") in denominations of $5 billion, $25 billion and $50 billion.

- 21 July: "agro cheque" for $100 billion.[92]

Inflation by 16 July officially surged to 2,200,000%[93] with some analysts estimating figures surpassing 9,000,000%.[94] As of 22 July 2008 the value of the ZWN fell to approximately 688 billion per US$1, or 688 trillion pre-August 2006 Zimbabwean dollars.[95]

| Date of redenomination | Currency code | Value |

|---|---|---|

| 1 August 2006 | ZWN | 1 000 ZWD |

| 1 August 2008 | ZWR | 1010 ZWN = 1013 ZWD |

| 2 February 2009 | ZWL | 1012 ZWR = 1022 ZWN = 1025 ZWD |

On 1 August 2008, the Zimbabwe dollar was redenominated at the ratio of 1010 ZWN to each third dollar (ZWR).[96] On 19 August 2008, official figures announced for June estimated the inflation over 11,250,000%.[97] Zimbabwe's annual inflation was 231,000,000% in July[98] (prices doubling every 17.3 days). By October 2008 Zimbabwe was mired in hyperinflation with wages falling far behind inflation. In this dysfunctional economy hospitals and schools had chronic staffing problems, because many nurses and teachers could not afford bus fare to work. Most of the capital of Harare was without water because the authorities had stopped paying the bills to buy and transport the treatment chemicals. Desperate for foreign currency to keep the government functioning, Zimbabwe's central bank governor, Gideon Gono, sent runners into the streets with suitcases of Zimbabwean dollars to buy up American dollars and South African rand.[99]

For periods after July 2008, no official inflation statistics were released. Prof. Steve H. Hanke overcame the problem by estimating inflation rates after July 2008 and publishing the Hanke Hyperinflation Index for Zimbabwe.[100] Prof. Hanke's HHIZ measure indicated that the inflation peaked at an annual rate of 89.7 sextillion percent (89,700,000,000,000,000,000,000%) in mid-November 2008. The peak monthly rate was 79.6 billion percent, which is equivalent to a 98% daily rate, or around 7×10108% yearly rate. At that rate, prices were doubling every 24.7 hours. Note that many of these figures should be considered mostly theoretical since hyperinflation did not proceed at this rate over a whole year.[101]

At its November 2008 peak, Zimbabwe's rate of inflation approached, but failed to surpass, Hungary's July 1946 world record.[101] On 2 February 2009, the dollar was redenominated for the third time at the ratio of 1012 ZWR to 1 ZWL, only three weeks after the $100 trillion banknote was issued on 16 January,[102][103] but hyperinflation waned by then as official inflation rates in USD were announced and foreign transactions were legalised,[101] and on 12 April the Zimbabwe dollar was abandoned in favour of using only foreign currencies. The overall impact of hyperinflation was US$1 = 1025 ZWD.

- Start and end date: March 2007 – mid November 2008

- Peak month and rate of inflation: mid November 2008, 7.96×1010%[104]

Examples of high inflation

Some countries experienced very high inflation, but did not reach hyperinflation, as defined as a monthly inflation rate of 50%.

Holy Roman Empire

Between 1620 and 1622 the Kreuzer fell from 1 Reichsthaler to 124 Kreuzer in end of 1619 to 1 Reichstaler to over 600 (regionally over 1000) Kreuzer in end of 1622, during the Thirty Years' War. This is a monthly inflation rate of over 20.6% (regionally over 34.4%).

Iraq

Between 1987 and 1995 the Iraqi Dinar went from an official value of 0.306 Dinars/USD (or US$3.26 per dinar, though the black market rate is thought to have been substantially lower) to 3,000 dinars/USD due to government printing of 10s of trillions of dinars starting with a base of only tens of billions. That equates to approximately 315% inflation per year averaged over that eight-year period.[105]

Mexico

In spite of increased oil prices in the late 1970s (Mexico is a producer and exporter), Mexico defaulted on its external debt in 1982. As a result, the country suffered a severe case of capital flight and several years of acute inflation and peso devaluation, leading to an accumulated inflation rate of almost 27,000% between December 1975 and late 1988. On 1 January 1993, Mexico created a new currency, the nuevo peso ("new peso", or MXN), which chopped three zeros off the old peso (One new peso was equal to 1,000 old MXP pesos).

Ecuador

Between 1998 and 1999, Ecuador faced a period of economic instability that resulted from a combined banking crisis, currency crisis, and sovereign debt crisis.[106] Severe inflation and devaluation of the Ecuadorean Sucre lead to President Jamil Mahuad announcing on 9 January 2000 that the US dollar would be adopted as the national currency.

Despite the government's efforts to curb inflation, the Sucre depreciated rapidly at the end of 1999, resulting in widespread informal use of U.S. dollars in the financial system. As a last resort to prevent hyperinflation, the government formally adopted the U.S. dollar in January 2000. The stability of the new currency was a necessary first step towards economic recovery, but the exchange rate was fixed at 25,000:1, which resulted in great losses of wealth.[107]

Roman Egypt

In Roman Egypt, where the best documentation on pricing has survived, the price of a measure of wheat was 200 drachmae in 276 AD, and increased to more than 2,000,000 drachmae in 334 AD, roughly 1,000,000% inflation in a span of 58 years.[108]

Although the price increased by a factor of 10,000 over 58 years, the annual rate of inflation was only 17.2% (1.4% monthly) compounded.

Romania

Romania experienced high inflation in the 1990s. The highest denomination in 1990 was 100 lei and in 1998 was 100,000 lei. By 2000 it was 500,000 lei. In early 2005 it was 1,000,000 lei. In July 2005 the lei was replaced by the new leu at 10,000 old lei = 1 new leu. Inflation in 2005 was 9%.[109] In July 2005 the highest denomination became 500 lei (= 5,000,000 old lei).

Transnistria

The Second Transnistrian ruble consisted solely of banknotes and suffered from high inflation, necessitating the issue of notes overstamped with higher denominations. 1 and sometimes 10 ruble become 10,000 ruble, 5 ruble become 50,000 and 10 ruble become 100,000 ruble. In 2000, a new ruble was introduced at a rate of 1 new ruble = 1,000,000 old rubles.

Turkey

Since the end of 2017 Turkey has high inflation rates. It is speculated that the new elections took place frustrated because of the impending crisis to forestall.[110][111][112] In October 2017, inflation was at 11.9%, the highest rate since July 2008.[113] The Turkish lira fall from 1.503 TRY = 1 US dollar in 2010 to 5.5695 TRY = 1 US dollar in August 2018.[114]

United States

During the Revolutionary War, when the Continental Congress authorized the printing of paper called continental currency, the monthly inflation rate reached a peak of 47% in November 1779 (Bernholz 2003: 48). These notes depreciated rapidly, giving rise to the expression "not worth a continental". One cause of the inflation was counterfeiting by the British, who ran a press on HMS Phoenix, moored in New York Harbor. The counterfeits were advertised and sold almost for the price of the paper they were printed on.[115]

During the U.S. Civil War between January 1861 and April 1865, the Confederate States decided to finance the war by printing money. The Lerner Commodity Price Index of leading cities in the eastern Confederacy states subsequently increased from 100 to 9,200 in that time.[116] In the final months of the Civil War, the Confederate dollar was almost worthless. Similarly, the Union government inflated its greenbacks, with the monthly rate peaking at 40% in March 1864 (Bernholz 2003: 107).[117]

Vietnam

Vietnam went through a period of chaos and high inflation in the late 1980s, with inflation peaking at 774% in 1988, after the country's "price-wage-currency" reform package, led by then-Deputy Prime Minister Trần Phương, had failed.[118] High inflation also occurred in the early stages of the socialist-oriented market economic reforms commonly referred to as the Đổi Mới.

Ten most severe hyperinflations in world history

| Highest monthly inflation rates in history[119][120] | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | Currency name | Month | Rate | Equivalent daily inflation rate | Time required for prices to double | Highest denomination |

| Hungarian pengő | July 1946 | 4.19×1016 % | 207.19% | 14.82 hours | 100 quintillion (1020) | |

| Zimbabwe dollar | November 2008 | 7.96×1010 % | 98.01% | 24.35 hours | 100 trillion (1014) | |

| Yugoslav dinar | January 1994 | 3.13×108 % | 64.63% | 1.39 days | 500 billion (5×1011) | |

| Republika Srpska dinar | January 1994 | 2.97×108 % | 64.35% | 1.40 days | 10 billion (10×1010) | |

| German Papiermark | October 1923 | 29,500% | 20.89% | 3.65 days | 100 trillion (1014) | |

| Greek drachma | October 1944 | 13,800% | 17.88% | 4.21 days | 100 billion (1011) | |

| Chinese yuan | April 1949 | 5,070% | 14.06% | 5.27 days | 6 billion | |

| Armenian dram and Russian ruble | November 1993 | 438% | 5.77% | 12.36 days | 50,000 (ruble) | |

| Turkmenistan manat | November 1993 | 429% | 5.71% | 12.48 days | 500 | |

| Taiwanese yen | August 1945 | 399% | 5.50% | 12.94 days | 1,000 | |

Units of inflation

Inflation rate is usually measured in percent per year. It can also be measured in percent per month or in price doubling time.

| Old price | New price 1 year later | New price 10 years later | New price 100 years later | (Annual) inflation [%] | Monthly inflation [%] | Price doubling time [years] | Zero add time [years] | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |

|

|

|

0.01 |

|

|

23028 | ||||||||||

| 1 |

|

|

|

0.1 |

|

|

2300 | ||||||||||

| 1 |

|

|

|

0.3 |

|

|

769 | ||||||||||

| 1 |

|

|

|

1 |

|

|

231 | ||||||||||

| 1 |

|

|

|

3 |

|

|

77.9 | ||||||||||

| 1 |

|

|

|

10 |

|

|

24.1 | ||||||||||

| 1 |

|

|

|

100 |

|

|

3.32 | ||||||||||

| 1 |

|

|

|

900 |

|

|

1 | ||||||||||

| 1 |

|

|

|

3000 |

|

|

0.671 (8 months) | ||||||||||

| 1 |

|

|

|

12874.63 |

|

|

0.4732 (5 ⅔ months) | ||||||||||

| 1 |

|

|

|

1014 |

|

|

0.0833 (1 month) | ||||||||||

| 1 |

|

|

|

1.67 × 1075 |

|

|

0.0137 (5 days) | ||||||||||

| 1 |

|

|

|

1.05 × 102,639 |

|

|

0.000379 (3.3 hours) | ||||||||||

Often, at redenominations, three zeroes are cut from the bills. It can be read from the table that if the (annual) inflation is for example 100%, it takes 3.32 years to produce one more zero on the price tags, or 3 × 3.32 = 9.96 years to produce three zeroes. Thus can one expect a redenomination to take place about 9.96 years after the currency was introduced.

See also

Notes

- A banknote with a value of one million krones was printed, but not issued.[27]

References

- O'Sullivan, Arthur; Steven M. Sheffrin (2003). Economics: Principles in action. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey 07458: Pearson Prentice Hall. pp. 341, 404. ISBN 0-13-063085-3.CS1 maint: location (link)

- Where's the Hyperinflation? Archived 2 August 2018 at the Wayback Machine, Forbes.com, 2012

- Bernholz, Peter 2003, chapter 5.3

- Palairet, Michael R. (2000). The Four Ends of the Greek Hyperinflation of 1941-1946. Museum Tusculanum Press. p. 10. ISBN 9788772895826. Archived from the original on 10 November 2015. Retrieved 27 June 2015.

- Robinson, Joan (1 January 1938). "Review of The Economics of Inflation". The Economic Journal. 48 (191): 507–513. doi:10.2307/2225440. JSTOR 2225440.

- Phillip Cagan, The Monetary Dynamics of Hyperinflation, in Milton Friedman (Editor), Studies in the Quantity Theory of Money, Chicago: University of Chicago Press (1956).

- International Accounting Standards. "IAS 29 — Financial Reporting in Hyperinflationary Economies". IASB. Archived from the original on 4 April 2012. Retrieved 10 April 2012.

- Bernholz, Peter 2003, chapter 5.2 and Table 5.1

- Parsson, Jens (1974). Dying of Money (Chapter 17: Velocity). Boston, MA: Wellspring Press. pp. 112–119.

- Hyperinflation: causes, cures Bernard Mufute, 2003-10-02, "Hyperinflation has its root cause in money growth, which is not supported by growth in the output of goods and services. Usually the excessive money supply growth is caused by financing of the government budget deficit through the printing of money."

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 September 2008. Retrieved 15 January 2010.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Süssmuth, Bernd; Wieschemeyer, Matthias (2017). "Progressive tax-like effects of inflation: Fact or myth? The U.S. post-war experience". Archived from the original on 26 April 2019. Retrieved 26 April 2019. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Wolfgang Chr. Fischer (Editor), German Hyperinflation 1922/23 – A Law and Economics Approach Archived 12 March 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Eul Verlag, Köln, Germany 2010, p. 124

- Montier, James (February 2013). "Hyperinflations, Hysteria, and False Memories". GMO LLC. Archived from the original on 1 July 2013. Retrieved 10 December 2014.

- "Controls blamed for U.S. energy woes", Los Angeles Times, 13 February 1977, Milton Friedman press conference in Los Angeles.

- Bernholz, Peter 2003

- Jefferson County Miracles Archived 19 January 2018 at the Wayback Machine, Wall Street Journal, 6 March 2008.

- Ludwig von Mises (1996). Human Action. Fox & Wilkes, San Francisco, 4th edition, 1986. p. 428. ISBN 0-930073-18-5.

- Aziz, John (7 August 2012). "The Cantillon Effect".

- 1 billion in the German long scale = 1000 milliard = 1 trillion US scale.

- "Values of the most important German Banknotes of the Inflation Period from 1920 – 1923". Archived from the original on 13 April 2004. Retrieved 3 May 2004.

- The Penniless Billionaires, Max Shapiro, New York Times Book Co., 1980, page 203, ISBN 0-8129-0923-2 Shipiro comments: "Of course, one must not forget the 5 pfennig!"

- Hanke, Steve H. (17 November 2008). "New Hyperinflation Index (HHIZ) Puts Zimbabwe Inflation at 89.7 sextillion percent". Cato Institute. Archived from the original on 13 November 2008. Retrieved 17 November 2008.

- Tran, Mark (31 July 2008). "Zimbabwe knocks 10 zeros off currency amid world's highest inflation". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 2 February 2017. Retrieved 17 December 2016.

- "This infographic shows how currency debasement contributed to the fall of Rome". Business Insider. Archived from the original on 11 October 2017. Retrieved 18 October 2017.

- Archived 19 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- "Austria - 1,000,000 Kronen (1 July 1924)". Bank Note Museum. Archived from the original on 18 January 2019. Retrieved 18 January 2019.

- Adam Fergusson (12 October 2010). When Money Dies: The Nightmare of Deficit Spending, Devaluation, and Hyperinflation in Weimar Germany. PublicAffairs. ISBN 978-1-58648-994-6.

- Adam Fergusson (2010). When Money Dies – The Nightmare of Deficit Spending, Devaluation, and Hyperinflation in Weimar Germany. Public Affairs – Perseus Books Group. p. 92. ISBN 978-1-58648-994-6.

- Sargent, T. J. (1986) Rational Expectations and Inflation, New York: Harper & Row.

- "Country Profile: Bolivia" (PDF). Library of Congress Federal Research Division. January 2006. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 July 2014. Retrieved 9 June 2019.

- "BCB - Calculadora do cidadão". www3.bcb.gov.br. Archived from the original on 1 May 2019. Retrieved 27 April 2019.

- Araujo, Vitor Hugo Alves de. "A tragédia da inflação brasileira - e se tivéssemos ouvido Mises?". Notas do Vitor. Archived from the original on 27 April 2019. Retrieved 27 April 2019.

- "Entenda os planos econômicos Bresser, Verão, Collor 1, Collor 2 e as perdas na poupança". G1 (in Portuguese). Archived from the original on 27 April 2019. Retrieved 27 April 2019.

- Araujo, Vitor Hugo Alves de. "GRAFICOS-merged.pdf". Archived from the original on 14 April 2019. Retrieved 27 April 2019.

- "O que foi o Plano Real?". Politize! (in Portuguese). 3 October 2017. Archived from the original on 14 April 2019. Retrieved 27 April 2019.

- Araujo, Vitor Hugo Alves de. "Índices de inflação IPCA e INPC desde 1979 até 2019". Notas do Vitor (in Portuguese). Archived from the original on 1 May 2019. Retrieved 1 May 2019.

- The Truth About Inflation, Chapter 2, Paul Donovan, Routledge 2015

- Chang, K. (1958) The Inflationary Spiral: The Experience in China, 1939–1950, New York: The Technology Press of Massachusetts Institute of Technology and John Wiley and Sons.

- Sandrock, J. E. "Bank notes of the French Revolution and First Republic" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 December 2013. Retrieved 18 November 2013.

- Stephen D. Dillaye, Assignats and Mandats: A True History, Including an Examination of Dr. Andrew Dickson White's 'Paper Money in France', (Philadelphia: Henry Carey Baird & Co, 1877)

- White, E. N. (1991). "Measuring the French Revolution's Inflation: the Tableaux de depreciation". Histoire & Mesure, 6 (3): 245–274.

- Adam Fergusson (2010). When Money Dies – The Nightmare of Deficit Spending, Devaluation, and Hyperinflation in Weimar Germany. Public Affairs – Perseus Books Group. p. 117. ISBN 978-1-58648-994-6.

- Lord D'Abernon (1930). An Ambassador of Peace, the diary of Viscount D'Abernon, Berlin 1920–1926 (V1–3). London: Hodder and Stoughton.

- "Bresciani-Turroni, page 335" (PDF). 18 August 2014. Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 September 2013. Retrieved 27 June 2015.

- Athanassios K. Boudalis (2016). Money in Greece, 1821-2001. The history of an institution. MIG Publishing. p. 618. ISBN 978-9-60937-758-4.

- Adam Fergusson (2010). When Money Dies – The Nightmare of Deficit Spending, Devaluation, and Hyperinflation in Weimar Germany. Perseus. p. 101. ISBN 978-1-58648-994-6.

- "Hungary: Postal history – Hyperinflation (part 2)". Archived from the original on 17 April 2011. Retrieved 29 January 2011.

- Judt, Tony (2006). Postwar: A History of Europe Since 1945. Penguin. p. 87. ISBN 0-14-303775-7.

- Zimbabwe hyperinflation 'will set world record within six weeks' Archived 14 November 2008 at the Wayback Machine Zimbabwe Situation 14 November 2008

- Nogaro, B. (1948) "Hungary's Recent Monetary Crisis and Its Theoretical Meaning", American Economic Review, 38 (4): 526–542.

- "Brightening the future of Korea". DailyNK. Archived from the original on 10 November 2012. Retrieved 15 October 2012.

- Tashu, Melesse (February 2015). "Drivers of Peru's Equilibrium Real Exchange Rate: Is the Nuevo Sol a Commodity Currency?" (PDF). IMF Working Paper: 6. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 June 2015. Retrieved 13 June 2019.

- "Hiperinflacja - Polish National Bank". www.nbportal.pl (in Polish). 7 May 2015. Archived from the original on 11 February 2017. Retrieved 11 February 2017.

- Barbara A. Noe (7 August 2005). "A Return to Wartime Philippines". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 17 February 2009. Retrieved 16 November 2006.

- Agoncillo, Teodoro A. & Guerrero, Milagros C., History of the Filipino People, 1986, R. P. Garcia Publishing Company, Quezon City, Philippines

- Hartendorp, A. (1958) History of Industry and Trade of the Philippines, Manila: American Chamber of Commerce on the Philippines, Inc.

- "Banana Money Exchange". The Straits Times. Archived from the original on 27 May 2015. Retrieved 27 May 2015.

- Hanke, Steve (18 August 2018). "Venezuela's Great Bolivar Scam, Nothing but a Face Lift". Forbes. Archived from the original on 19 August 2018. Retrieved 19 August 2018.

- "Venezuela 2014 inflation hits 68.5 pct -central bank". Archived from the original on 9 May 2019. Retrieved 5 April 2018.

- "Venezuela annual inflation 180 percent". Reuters. 1 October 2015. Archived from the original on 27 October 2017. Retrieved 15 November 2017.

- "The Three Countries with the Highest Inflation". Archived from the original on 24 February 2019. Retrieved 5 April 2018.

- Cristóbal Nagel, Juan (13 July 2015). "Looking into the Black Box of Venezuela's Economy". Foreign Policy. Archived from the original on 14 July 2015. Retrieved 14 July 2015.

- "Venezuela annual inflation 180 percent: opposition newspaper". Archived from the original on 27 October 2017. Retrieved 5 April 2018.

- Venezuela country profile (Economy tab), Archived 4 August 2019 at the Wayback Machine World in Figures. Retrieved 14 June 2017.

- Sequera, Vivian (21 February 2018). "Venezuelans report big weight losses in 2017 as hunger hits". Reuters. Archived from the original on 22 February 2018. Retrieved 23 February 2018.

- Corina, Pons (20 January 2017). "Venezuela 2016 inflation hits 800 percent, GDP shrinks 19 percent: document". Reuters. Archived from the original on 15 November 2017. Retrieved 15 November 2017.

- "AssetMacro". Archived from the original on 16 February 2017. Retrieved 15 February 2017.

- Davies, Wyre (20 February 2016). "Venezuela's decline fuelled by plunging oil prices". BBC News, Latin America. Archived from the original on 21 February 2016. Retrieved 20 February 2016.

- "Inflación de 2018 cerró en 1.698.488%, según la Asamblea Nacional" (in Spanish). Efecto Cocuyo. 9 January 2019. Archived from the original on 10 January 2019. Retrieved 9 January 2019.

- Herrero, Ana Vanessa; Malkin, Elisabeth (16 January 2017). "Venezuela Issues New Bank Notes Because of Hyperinflation". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 31 July 2017. Retrieved 17 January 2017.

- Krauze, Enrique (8 March 2018). "Hell of a Fiesta". New York Review of Books. Archived from the original on 22 February 2018. Retrieved 1 March 2018.

- Rosati, Andrew (5 December 2017). "Desperate Venezuelans Turn to Video Games to Survive". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on 6 December 2017. Retrieved 6 December 2017.

- "Tiendas de ropa eliminan etiquetas y habladores para agilizar aumento de precios". Diario La Region (in Spanish). 12 December 2017. Archived from the original on 15 December 2017. Retrieved 16 December 2017.

- Amaro, Silvia (27 July 2018). "Venezuelan inflation predicted to hit 1 million percent this year". CNBC. Archived from the original on 28 July 2018. Retrieved 29 July 2018.

- Hanke, Steve (31 July 2018). "IMF Produces Another Bogus Venezuela Inflation Forecast". Forbes. Archived from the original on 31 August 2018. Retrieved 31 August 2018.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 29 May 2019. Retrieved 18 May 2019.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Au Venezuela, l'inflation a été de 130 060 % en 2018". Le Monde (in French). 29 May 2019. Archived from the original on 30 May 2019. Retrieved 31 May 2019.

- "BCV admits hyperinflation of 53,798,500% since 2016". Venezuela Al Dia (in Spanish). 28 May 2019. Archived from the original on 29 May 2019. Retrieved 5 June 2019.

- Long, Gideon (29 May 2019). "Venezuela data offer rare glimpse of economic chaos". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 30 May 2019. Retrieved 31 May 2019.

- Wroughton, Lesley; Pons, Corina (30 May 2019). "IMF denies pressuring Venezuela to release economic data". Reuters. Archived from the original on 30 May 2019. Retrieved 31 May 2019.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 22 May 2018. Retrieved 26 May 2018.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "El Parlamento venezolano cree que la inflación llegará al 4.300.000 % en 2018". Yahoo. EFE. 8 October 2018. Archived from the original on 8 October 2018. Retrieved 8 October 2018.

- "Where Zillion Loses Meaning". The New York Times. 31 December 1993.

- Rostowski, J. (1998) Macroeconomics Instability in Post-Communist Countries, New York: Carendon Press.

- "Mugabe warns of business take-overs". BBC News. 1 July 2002. Archived from the original on 2 August 2018. Retrieved 2 August 2018.

- "Zimbabwe: Industry Allays Fears of Shortages". allAfrica. 26 September 2017. Archived from the original on 2 August 2018. Retrieved 2 August 2018.

- "Zimbabwe famine". Archived from the original on 8 January 2009. Retrieved 10 March 2009.

- Greenspan, Alan. The Age of Turbulence: Adventures in a New World. New York: The Penguin Press. 2007. Page 339.

- "Zimbabwe issues 250 mn dollar banknote to tackle price spiral- International Business-News-The Economic Times". Archived from the original on 11 January 2009. Retrieved 8 May 2008.

- "Zimbabwe bank issues $500m note". BBC News. 15 May 2008. Archived from the original on 19 May 2008. Retrieved 15 May 2008.

- "Zimbabwe inflation at 2,200,000%". BBC News. 16 July 2008. Archived from the original on 30 September 2009. Retrieved 26 March 2010.

- "Inflation gallops ahead: 9000 000%". The Zimbabwe Independent. 26 June 2008. Archived from the original on 9 August 2011. Retrieved 15 October 2012.

- "ZimbabweanEQUITIES". Archived from the original on 20 August 2008. Retrieved 30 June 2008.

- Dzirutwe, MacDonald (9 December 2014). "Zimbabwe's Mugabe fires deputy, seven ministers". Reuters. Archived from the original on 13 December 2014. Retrieved 10 December 2014.

- "Zimbabwe inflation rockets higher". BBC News. 19 August 2008. Archived from the original on 24 February 2010. Retrieved 26 March 2010.

- Celia W. Dugger (1 October 2008). "Life in Zimbabwe: Wait for Useless Money". The New York Times. Retrieved 25 September 2019.

- Steve H. Hanke. "New Hyperinflation Index (HHIZ) Puts Zimbabwe Inflation at 89.7 Sextillion Percent". Washington, D.C.: Cato Institute. (Retrieved 17 November 2008) Archived 12 November 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- Steve H. Hanke and Alex K. F. Kwok. "On the Measurement of Zimbabwe's Hyperinflation". Cato Journal, Vol. 29, No. 2 (Spring/Summer 2009).

- Archived 19 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- "Zimbabwe dollar sheds 12 zeros". BBC News. 2 February 2009. Archived from the original on 3 February 2009. Retrieved 2 February 2008.

- Hanke, S. H. and Kwok, A. K. F. (2009). "On the Measurement of Zimbabwe's Hyperinflation". Cato Journal, 29 (2): 353–364.

- "History page at the Central Bank of Iraq". Archived from the original on 1 May 2012. Retrieved 26 June 2012.

- Montiel, Peter, J. (2014). "Ecuador 1999: triple crisis and dollarization". Ten Crises. London: Routledge.

- Jácome, Luis Ignacio; LJácome@imf.org (2004). "The Late 1990s Financial Crisis in Ecuador: Institutional Weaknesses, Fiscal Rigidities, and Financial Dollarization at Work". IMF Working Papers. 04 (12): 1. doi:10.5089/9781451842937.001.

- The Life Contributors (17 April 2012). "Traveling in Europe Has Become Absurdly Expensive—And You Know The Reason Why". Business Insider. Archived from the original on 15 May 2012. Retrieved 15 October 2012.

- "Report for Selected Countries and Subjects". International Monetary Fund. 29 April 2003. Archived from the original on 18 October 2012. Retrieved 15 October 2012.

- "Der wahre Grund, warum Erdoğan die Wahlen vorzieht". Business Insider. 18 April 2018. Retrieved 3 August 2018.

- "Warum Erdogan es so eilig hat". Wirtschaftswoche. 19 April 2018. Retrieved 3 August 2018.

- "Erdogan kündigt Neuwahlen im Juni an". Hannoversche Allgemeine Zeitung. 18 April 2018. Archived from the original on 3 August 2018. Retrieved 3 August 2018.

- "Lira fällt Richtung Rekordtief". Handelsblatt. 3 November 2017. Retrieved 3 August 2018.

- "Dollar - Türkische Lira". Finanzen.net GmbH. 3 August 2018. Archived from the original on 3 August 2018. Retrieved 3 August 2018.

- Craughwell, Thomas J. (2007). Stealing Lincoln's Body. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, p. 33

- Weidenmier, Marc, Money and Finance in the Confederate States of America, Claremont McKenna College, archived from the original on 28 September 2013, retrieved 10 June 2016

- "Steve H. Hanke and Alex K. F. Kwok. "On the Measurement of Zimbabwe's Hyperinflation". Cato Journal, Vol. 29, No. 2 (Spring/Summer 2009)" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 January 2010.

- Napier, Nancy K.; Vuong, Quan Hoang (2013). What we see, why we worry, why we hope: Vietnam going forward. Boise, Idaho: Boise State University CCI Press. p. 140. ISBN 978-0985530587.

- "World Hyperinflations | Steve H. Hanke and Nicholas Krus | Cato Institute: Working Paper". Cato.org. 15 August 2012. Archived from the original on 17 October 2012. Retrieved 15 October 2012.

- "World Hyperinflations" (PDF). CNBC. 14 February 2011. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 September 2013. Retrieved 13 July 2012.

Further reading

- Peter Bernholz (30 April 2015). Monetary Regimes and Inflation: History, Economic and Political Relationships, Second Edition. Edward Elgar Publishing. ISBN 978-1-78471-763-6.