Electronegativity

Electronegativity, symbol χ, measures the tendency of an atom to attract a shared pair of electrons (or electron density).[1] An atom's electronegativity is affected by both its atomic number and the distance at which its valence electrons reside from the charged nucleus. The higher the associated electronegativity, the more an atom or a substituent group attracts electrons.

On the most basic level, electronegativity is determined by factors like the nuclear charge (the more protons an atom has, the more "pull" it will have on electrons) and the number and location of other electrons in the atomic shells (the more electrons an atom has, the farther from the nucleus the valence electrons will be, and as a result the less positive charge they will experience—both because of their increased distance from the nucleus, and because the other electrons in the lower energy core orbitals will act to shield the valence electrons from the positively charged nucleus).

The opposite of electronegativity is electropositivity: a measure of an element's ability to donate electrons.

The term "electronegativity" was introduced by Jöns Jacob Berzelius in 1811,[2] though the concept was known before that and was studied by many chemists including Avogadro.[2] In spite of its long history, an accurate scale of electronegativity was not developed until 1932, when Linus Pauling proposed an electronegativity scale which depends on bond energies, as a development of valence bond theory.[3] It has been shown to correlate with a number of other chemical properties. Electronegativity cannot be directly measured and must be calculated from other atomic or molecular properties. Several methods of calculation have been proposed, and although there may be small differences in the numerical values of the electronegativity, all methods show the same periodic trends between elements.

The most commonly used method of calculation is that originally proposed by Linus Pauling. This gives a dimensionless quantity, commonly referred to as the Pauling scale (χr), on a relative scale running from 0.79 to 3.98 (hydrogen = 2.20). When other methods of calculation are used, it is conventional (although not obligatory) to quote the results on a scale that covers the same range of numerical values: this is known as an electronegativity in Pauling units.

As it is usually calculated, electronegativity is not a property of an atom alone, but rather a property of an atom in a molecule.[4] Properties of a free atom include ionization energy and electron affinity. It is to be expected that the electronegativity of an element will vary with its chemical environment,[5] but it is usually considered to be a transferable property, that is to say that similar values will be valid in a variety of situations.

Caesium is the least electronegative element (0.79); fluorine is the most (3.98). Francium and caesium were originally both assigned 0.7; caesium's value was later refined to 0.79, but no experimental data allows a similar refinement for francium. However, francium's ionization energy is known to be slightly higher than caesium's, in accordance with the relativistic stabilization of the 7s orbital, and this in turn implies that francium is in fact more electronegative than caesium.

Electronegativities of the elements

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group → | |||||||||||||||||||

| ↓ Period | |||||||||||||||||||

| 1 | H 2.20 |

He | |||||||||||||||||

| 2 | Li 0.98 |

Be 1.57 |

B 2.04 |

C 2.55 |

N 3.04 |

O 3.44 |

F 3.98 |

Ne | |||||||||||

| 3 | Na 0.93 |

Mg 1.31 |

Al 1.61 |

Si 1.90 |

P 2.19 |

S 2.58 |

Cl 3.16 |

Ar | |||||||||||

| 4 | K 0.82 |

Ca 1.00 |

Sc 1.36 |

Ti 1.54 |

V 1.63 |

Cr 1.66 |

Mn 1.55 |

Fe 1.83 |

Co 1.88 |

Ni 1.91 |

Cu 1.90 |

Zn 1.65 |

Ga 1.81 |

Ge 2.01 |

As 2.18 |

Se 2.55 |

Br 2.96 |

Kr 3.00 | |

| 5 | Rb 0.82 |

Sr 0.95 |

Y 1.22 |

Zr 1.33 |

Nb 1.6 |

Mo 2.16 |

Tc 1.9 |

Ru 2.2 |

Rh 2.28 |

Pd 2.20 |

Ag 1.93 |

Cd 1.69 |

In 1.78 |

Sn 1.96 |

Sb 2.05 |

Te 2.1 |

I 2.66 |

Xe 2.60 | |

| 6 | Cs 0.79 |

Ba 0.89 |

La 1.1 |

Hf 1.3 |

Ta 1.5 |

W 2.36 |

Re 1.9 |

Os 2.2 |

Ir 2.20 |

Pt 2.28 |

Au 2.54 |

Hg 2.00 |

Tl 1.62 |

Pb 1.87 |

Bi 2.02 |

Po 2.0 |

At 2.2 |

Rn 2.2 | |

| 7 | Fr >0.79[en 1] |

Ra 0.9 |

Ac 1.1 |

Rf |

Db |

Sg |

Bh |

Hs |

Mt |

Ds |

Rg |

Cn |

Nh |

Fl |

Mc |

Lv |

Ts |

Og | |

| Ce 1.12 |

Pr 1.13 |

Nd 1.14 |

Pm 1.13 |

Sm 1.17 |

Eu 1.2 |

Gd 1.2 |

Tb 1.1 |

Dy 1.22 |

Ho 1.23 |

Er 1.24 |

Tm 1.25 |

Yb 1.1 |

Lu 1.27 | ||||||

| Th 1.3 |

Pa 1.5 |

U 1.38 |

Np 1.36 |

Pu 1.28 |

Am 1.13 |

Cm 1.28 |

Bk 1.3 |

Cf 1.3 |

Es 1.3 |

Fm 1.3 |

Md 1.3 |

No 1.3 |

Lr 1.3[en 2] | ||||||

Each value is given for the most common and stable oxidation state of the element.

See also: Electronegativities of the elements (data page)

- The electronegativity of francium was chosen by Pauling as 0.7, close to that of caesium (also assessed 0.7 at that point). The base value of hydrogen was later increased by 0.10 and caesium's electronegativity was later refined to 0.79; however, no refinements have been made for francium as no experiment has been conducted. However, francium is expected and, to a small extent, observed to be more electronegative than caesium. See francium for details.

- See Brown, Geoffrey (2012). The Inaccessible Earth: An integrated view to its structure and composition. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 88. ISBN 9789401115162.

Methods of calculation

Pauling electronegativity

Pauling first proposed[3] the concept of electronegativity in 1932 to explain why the covalent bond between two different atoms (A–B) is stronger than the average of the A–A and the B–B bonds. According to valence bond theory, of which Pauling was a notable proponent, this "additional stabilization" of the heteronuclear bond is due to the contribution of ionic canonical forms to the bonding.

The difference in electronegativity between atoms A and B is given by:

where the dissociation energies, Ed, of the A–B, A–A and B–B bonds are expressed in electronvolts, the factor (eV)−1⁄2 being included to ensure a dimensionless result. Hence, the difference in Pauling electronegativity between hydrogen and bromine is 0.73 (dissociation energies: H–Br, 3.79 eV; H–H, 4.52 eV; Br–Br 2.00 eV)

As only differences in electronegativity are defined, it is necessary to choose an arbitrary reference point in order to construct a scale. Hydrogen was chosen as the reference, as it forms covalent bonds with a large variety of elements: its electronegativity was fixed first[3] at 2.1, later revised[6] to 2.20. It is also necessary to decide which of the two elements is the more electronegative (equivalent to choosing one of the two possible signs for the square root). This is usually done using "chemical intuition": in the above example, hydrogen bromide dissolves in water to form H+ and Br− ions, so it may be assumed that bromine is more electronegative than hydrogen. However, in principle, since the same electronegativities should be obtained for any two bonding compounds, the data are in fact overdetermined, and the signs are unique once a reference point is fixed (usually, for H or F).

To calculate Pauling electronegativity for an element, it is necessary to have data on the dissociation energies of at least two types of covalent bond formed by that element. A. L. Allred updated Pauling's original values in 1961 to take account of the greater availability of thermodynamic data,[6] and it is these "revised Pauling" values of the electronegativity that are most often used.

The essential point of Pauling electronegativity is that there is an underlying, quite accurate, semi-empirical formula for dissociation energies, namely:

or sometimes, a more accurate fit

This is an approximate equation, but holds with good accuracy. Pauling obtained it by noting that a bond can be approximately represented as a quantum mechanical superposition of a covalent bond and two ionic bond-states. The covalent energy of a bond is approximately, by quantum mechanical calculations, the geometric mean of the two energies of covalent bonds of the same molecules, and there is an additional energy that comes from ionic factors, i.e. polar character of the bond.

The geometric mean is approximately equal to the arithmetic mean - which is applied in the first formula above - when the energies are of the similar value, e.g., except for the highly electropositive elements, where there is a larger difference of two dissociation energies; the geometric mean is more accurate and almost always gives a positive excess energy, due to ionic bonding. The square root of this excess energy, Pauling notes, is approximately additive, and hence one can introduce the electronegativity. Thus, it is this semi-empirical formula for bond energy that underlies Pauling electronegativity concept.

The formulas are approximate, but this rough approximation is in fact relatively good and gives the right intuition, with the notion of polarity of the bond and some theoretical grounding in quantum mechanics. The electronegativities are then determined to best fit the data.

In more complex compounds, there is additional error since electronegativity depends on the molecular environment of an atom. Also, the energy estimate can be only used for single, not for multiple bonds. The energy of formation of a molecule containing only single bonds then can be approximated from an electronegativity table, and depends on the constituents and sum of squares of differences of electronegativities of all pairs of bonded atoms. Such a formula for estimating energy typically has relative error of order of 10%, but can be used to get a rough qualitative idea and understanding of a molecule.

Mulliken electronegativity

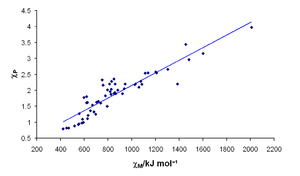

Robert S. Mulliken proposed that the arithmetic mean of the first ionization energy (Ei) and the electron affinity (Eea) should be a measure of the tendency of an atom to attract electrons.[7][8] As this definition is not dependent on an arbitrary relative scale, it has also been termed absolute electronegativity,[9] with the units of kilojoules per mole or electronvolts.

However, it is more usual to use a linear transformation to transform these absolute values into values that resemble the more familiar Pauling values. For ionization energies and electron affinities in electronvolts,[10]

and for energies in kilojoules per mole,[11]

The Mulliken electronegativity can only be calculated for an element for which the electron affinity is known, fifty-seven elements as of 2006. The Mulliken electronegativity of an atom is sometimes said to be the negative of the chemical potential.[12] By inserting the energetic definitions of the ionization potential and electron affinity into the Mulliken electronegativity, it is possible to show that the Mulliken chemical potential is a finite difference approximation of the electronic energy with respect to the number of electrons., i.e.,

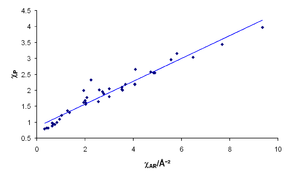

Allred–Rochow electronegativity

A. Louis Allred and Eugene G. Rochow considered[13] that electronegativity should be related to the charge experienced by an electron on the "surface" of an atom: The higher the charge per unit area of atomic surface the greater the tendency of that atom to attract electrons. The effective nuclear charge, Zeff, experienced by valence electrons can be estimated using Slater's rules, while the surface area of an atom in a molecule can be taken to be proportional to the square of the covalent radius, rcov. When rcov is expressed in picometres,[14]

Sanderson electronegativity equalization

R.T. Sanderson has also noted the relationship between Mulliken electronegativity and atomic size, and has proposed a method of calculation based on the reciprocal of the atomic volume.[15] With a knowledge of bond lengths, Sanderson's model allows the estimation of bond energies in a wide range of compounds.[16] Sanderson's model has also been used to calculate molecular geometry, s-electrons energy, NMR spin-spin constants and other parameters for organic compounds.[17][18] This work underlies the concept of electronegativity equalization, which suggests that electrons distribute themselves around a molecule to minimize or to equalize the Mulliken electronegativity.[19] This behavior is analogous to the equalization of chemical potential in macroscopic thermodynamics.[20]

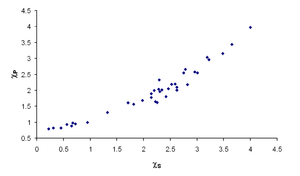

Allen electronegativity

Perhaps the simplest definition of electronegativity is that of Leland C. Allen, who has proposed that it is related to the average energy of the valence electrons in a free atom,[21] [22] [23]

where εs,p are the one-electron energies of s- and p-electrons in the free atom and ns,p are the number of s- and p-electrons in the valence shell. It is usual to apply a scaling factor, 1.75×10−3 for energies expressed in kilojoules per mole or 0.169 for energies measured in electronvolts, to give values that are numerically similar to Pauling electronegativities.

The one-electron energies can be determined directly from spectroscopic data, and so electronegativities calculated by this method are sometimes referred to as spectroscopic electronegativities. The necessary data are available for almost all elements, and this method allows the estimation of electronegativities for elements that cannot be treated by the other methods, e.g. francium, which has an Allen electronegativity of 0.67.[24] However, it is not clear what should be considered to be valence electrons for the d- and f-block elements, which leads to an ambiguity for their electronegativities calculated by the Allen method.

In this scale neon has the highest electronegativity of all elements, followed by fluorine, helium, and oxygen.

Electronegativity using the Allen scale | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group → | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 |

| ↓ Period | ||||||||||||||||||

| 1 | H 2.300 |

He 4.160 | ||||||||||||||||

| 2 | Li 0.912 |

Be 1.576 |

B 2.051 |

C 2.544 |

N 3.066 |

O 3.610 |

F 4.193 |

Ne 4.787 | ||||||||||

| 3 | Na 0.869 |

Mg 1.293 |

Al 1.613 |

Si 1.916 |

P 2.253 |

S 2.589 |

Cl 2.869 |

Ar 3.242 | ||||||||||

| 4 | K 0.734 |

Ca 1.034 |

Sc 1.19 |

Ti 1.38 |

V 1.53 |

Cr 1.65 |

Mn 1.75 |

Fe 1.80 |

Co 1.84 |

Ni 1.88 |

Cu 1.85 |

Zn 1.588 |

Ga 1.756 |

Ge 1.994 |

As 2.211 |

Se 2.424 |

Br 2.685 |

Kr 2.966 |

| 5 | Rb 0.706 |

Sr 0.963 |

Y 1.12 |

Zr 1.32 |

Nb 1.41 |

Mo 1.47 |

Tc 1.51 |

Ru 1.54 |

Rh 1.56 |

Pd 1.58 |

Ag 1.87 |

Cd 1.521 |

In 1.656 |

Sn 1.824 |

Sb 1.984 |

Te 2.158 |

I 2.359 |

Xe 2.582 |

| 6 | Cs 0.659 |

Ba 0.881 |

Lu 1.09 |

Hf 1.16 |

Ta 1.34 |

W 1.47 |

Re 1.60 |

Os 1.65 |

Ir 1.68 |

Pt 1.72 |

Au 1.92 |

Hg 1.765 |

Tl 1.789 |

Pb 1.854 |

Bi 2.01 |

Po 2.19 |

At 2.39 |

Rn 2.60 |

| 7 | Fr 0.67 |

Ra 0.89 | ||||||||||||||||

| See also: Electronegativities of the elements (data page) | ||||||||||||||||||

Correlation of electronegativity with other properties

The wide variety of methods of calculation of electronegativities, which all give results that correlate well with one another, is one indication of the number of chemical properties which might be affected by electronegativity. The most obvious application of electronegativities is in the discussion of bond polarity, for which the concept was introduced by Pauling. In general, the greater the difference in electronegativity between two atoms the more polar the bond that will be formed between them, with the atom having the higher electronegativity being at the negative end of the dipole. Pauling proposed an equation to relate "ionic character" of a bond to the difference in electronegativity of the two atoms,[4] although this has fallen somewhat into disuse.

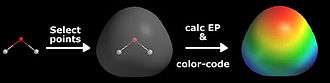

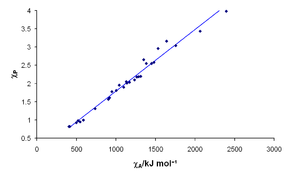

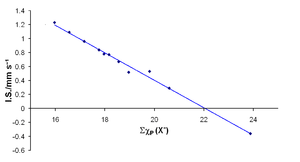

Several correlations have been shown between infrared stretching frequencies of certain bonds and the electronegativities of the atoms involved:[25] however, this is not surprising as such stretching frequencies depend in part on bond strength, which enters into the calculation of Pauling electronegativities. More convincing are the correlations between electronegativity and chemical shifts in NMR spectroscopy[26] or isomer shifts in Mössbauer spectroscopy[27] (see figure). Both these measurements depend on the s-electron density at the nucleus, and so are a good indication that the different measures of electronegativity really are describing "the ability of an atom in a molecule to attract electrons to itself".[1][4]

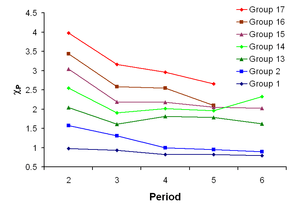

Trends in electronegativity

Periodic trends

In general, electronegativity increases on passing from left to right along a period, and decreases on descending a group. Hence, fluorine is the most electronegative of the elements (not counting noble gases), whereas caesium is the least electronegative, at least of those elements for which substantial data is available.[24] This would lead one to believe that caesium fluoride is the compound whose bonding features the most ionic character.

There are some exceptions to this general rule. Gallium and germanium have higher electronegativities than aluminium and silicon, respectively, because of the d-block contraction. Elements of the fourth period immediately after the first row of the transition metals have unusually small atomic radii because the 3d-electrons are not effective at shielding the increased nuclear charge, and smaller atomic size correlates with higher electronegativity (see Allred-Rochow electronegativity, Sanderson electronegativity above). The anomalously high electronegativity of lead, in particular when compared to thallium and bismuth, is an artifact of electronegativity varying with oxidation state: its electronegativity conforms better to trends if it is quoted for the +2 state instead of the +4 state.

Variation of electronegativity with oxidation number

In inorganic chemistry it is common to consider a single value of the electronegativity to be valid for most "normal" situations. While this approach has the advantage of simplicity, it is clear that the electronegativity of an element is not an invariable atomic property and, in particular, increases with the oxidation state of the element.

Allred used the Pauling method to calculate separate electronegativities for different oxidation states of the handful of elements (including tin and lead) for which sufficient data was available.[6] However, for most elements, there are not enough different covalent compounds for which bond dissociation energies are known to make this approach feasible. This is particularly true of the transition elements, where quoted electronegativity values are usually, of necessity, averages over several different oxidation states and where trends in electronegativity are harder to see as a result.

| Acid | Formula | Chlorine oxidation state |

pKa |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hypochlorous acid | HClO | +1 | +7.5 |

| Chlorous acid | HClO2 | +3 | +2.0 |

| Chloric acid | HClO3 | +5 | –1.0 |

| Perchloric acid | HClO4 | +7 | –10 |

The chemical effects of this increase in electronegativity can be seen both in the structures of oxides and halides and in the acidity of oxides and oxoacids. Hence CrO3 and Mn2O7 are acidic oxides with low melting points, while Cr2O3 is amphoteric and Mn2O3 is a completely basic oxide.

The effect can also be clearly seen in the dissociation constants of the oxoacids of chlorine. The effect is much larger than could be explained by the negative charge being shared among a larger number of oxygen atoms, which would lead to a difference in pKa of log10(1⁄4) = –0.6 between hypochlorous acid and perchloric acid. As the oxidation state of the central chlorine atom increases, more electron density is drawn from the oxygen atoms onto the chlorine, diminishing the partial negative charge of individual oxygen atoms. At the same time, the positive partial charge on the hydrogen increases with higher oxidation state. This explains the observed increased acidity with increasing oxidation state in the oxoacids of chlorine.

Electronegativity and hybridization scheme

The electronegativity of an atom changes depending on the hybridization of the orbital employed in bonding. Electrons in s orbitals are held more tightly than electrons in p orbitals. Hence, a bond to an atom that employs an spx hybrid orbital for bonding will be more heavily polarized to that atom when the hybrid orbital has more s character. That is, when electronegativities are compared for different hybridization schemes of a given element, the order χ(sp3) < χ(sp2) < χ(sp) holds (the trend should apply to non-integer hybridization indices as well). While this holds true in principle for any main-group element, values for the hybridization-specific electronegativity are most frequently cited for carbon. In organic chemistry, these electronegativities are frequently invoked to predict or rationalize bond polarities in organic compounds containing double and triple bonds to carbon.

| Hybridization | χ (Pauling)[28] |

|---|---|

| C(sp3) | 2.3 |

| C(sp2) | 2.6 |

| C(sp) | 3.1 |

| 'generic' C | 2.5 |

Group electronegativity

In organic chemistry, electronegativity is associated more with different functional groups than with individual atoms. The terms group electronegativity and substituent electronegativity are used synonymously. However, it is common to distinguish between the inductive effect and the resonance effect, which might be described as σ- and π-electronegativities, respectively. There are a number of linear free-energy relationships that have been used to quantify these effects, of which the Hammett equation is the best known. Kabachnik parameters are group electronegativities for use in organophosphorus chemistry.

Electropositivity

Electropositivity is a measure of an element's ability to donate electrons, and therefore form positive ions; thus, it is opposed to electronegativity.

Mainly, this is an attribute of metals, meaning that, in general, the greater the metallic character of an element the greater the electropositivity. Therefore, the alkali metals are most electropositive of all. This is because they have a single electron in their outer shell and, as this is relatively far from the nucleus of the atom, it is easily lost; in other words, these metals have low ionization energies.[29]

While electronegativity increases along periods in the periodic table, and decreases down groups, electropositivity decreases along periods (from left to right) and increases down groups. This means that elements in the upper right of the periodic table of elements (oxygen, sulfur, chlorine, etc.) will have the greatest electronegativity, and those in the lower left (rubidium, cesium, and francium) the greatest electropositivity.

References

- IUPAC, Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 2nd ed. (the "Gold Book") (1997). Online corrected version: (2006–) "Electronegativity". doi:10.1351/goldbook.E01990

- Jensen, W.B. (1996). "Electronegativity from Avogadro to Pauling: Part 1: Origins of the Electronegativity Concept". Journal of Chemical Education. 73 (1): 11–20. Bibcode:1996JChEd..73...11J. doi:10.1021/ed073p11.

- Pauling, L. (1932). "The Nature of the Chemical Bond. IV. The Energy of Single Bonds and the Relative Electronegativity of Atoms". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 54 (9): 3570–3582. doi:10.1021/ja01348a011.

- Pauling, Linus (1960). Nature of the Chemical Bond. Cornell University Press. pp. 88–107. ISBN 978-0-8014-0333-0.

- Greenwood, N. N.; Earnshaw, A. (1984). Chemistry of the Elements. Pergamon. p. 30. ISBN 978-0-08-022057-4.

- Allred, A. L. (1961). "Electronegativity values from thermochemical data". Journal of Inorganic and Nuclear Chemistry. 17 (3–4): 215–221. doi:10.1016/0022-1902(61)80142-5.

- Mulliken, R. S. (1934). "A New Electroaffinity Scale; Together with Data on Valence States and on Valence Ionization Potentials and Electron Affinities". Journal of Chemical Physics. 2 (11): 782–793. Bibcode:1934JChPh...2..782M. doi:10.1063/1.1749394.

- Mulliken, R. S. (1935). "Electronic Structures of Molecules XI. Electroaffinity, Molecular Orbitals and Dipole Moments". J. Chem. Phys. 3 (9): 573–585. Bibcode:1935JChPh...3..573M. doi:10.1063/1.1749731.

- Pearson, R. G. (1985). "Absolute electronegativity and absolute hardness of Lewis acids and bases". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 107 (24): 6801–6806. doi:10.1021/ja00310a009.

- Huheey, J. E. (1978). Inorganic Chemistry (2nd Edn.). New York: Harper & Row. p. 167.

- This second relation has been recalculated using the best values of the first ionization energies and electron affinities available in 2006.

- Franco-Pérez, Marco; Gázquez, José L. (31 October 2019). "Electronegativities of Pauling and Mulliken in Density Functional Theory". Journal of Physical Chemistry A. 123 (46): 10065–10071. Retrieved 5 July 2020.

- Allred, A. L.; Rochow, E. G. (1958). "A scale of electronegativity based on electrostatic force". Journal of Inorganic and Nuclear Chemistry. 5 (4): 264–268. doi:10.1016/0022-1902(58)80003-2.

- Housecroft C.E. and Sharpe A.G. Inorganic Chemistry (2nd ed., Pearson Prentice-Hall 2005) p.38

- Sanderson, R. T. (1983). "Electronegativity and bond energy". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 105 (8): 2259–2261. doi:10.1021/ja00346a026.

- Sanderson, R. T. (1983). Polar Covalence. New York: Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-618080-0.

- Zefirov, N. S.; Kirpichenok, M. A.; Izmailov, F. F.; Trofimov, M. I. (1987). "Calculation schemes for atomic electronegativities in molecular graphs within the framework of Sanderson principle". Doklady Akademii Nauk SSSR. 296: 883–887.

- Trofimov, M. I.; Smolenskii, E. A. (2005). "Application of the electronegativity indices of organic molecules to tasks of chemical informatics". Russian Chemical Bulletin. 54 (9): 2235–2246. doi:10.1007/s11172-006-0105-6.

- SW Rick; SJ Stuart (2002). "Electronegativity equalization models". In Kenny B. Lipkowitz; Donald B. Boyd (eds.). Reviews in computational chemistry. Wiley. p. 106. ISBN 978-0-471-21576-9.

- Robert G. Parr; Weitao Yang (1994). Density-functional theory of atoms and molecules. Oxford University Press. p. 91. ISBN 978-0-19-509276-9.

- Allen, Leland C. (1989). "Electronegativity is the average one-electron energy of the valence-shell electrons in ground-state free atoms". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 111 (25): 9003–9014. doi:10.1021/ja00207a003.

- Mann, Joseph B.; Meek, Terry L.; Allen, Leland C. (2000). "Configuration Energies of the Main Group Elements". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 122 (12): 2780–2783. doi:10.1021/ja992866e.

- Mann, Joseph B.; Meek, Terry L.; Knight, Eugene T.; Capitani, Joseph F.; Allen, Leland C. (2000). "Configuration energies of the d-block elements". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 122 (21): 5132–5137. doi:10.1021/ja9928677.

- The widely quoted Pauling electronegativity of 0.7 for francium is an extrapolated value of uncertain provenance. The Allen electronegativity of caesium is 0.66.

- See, e.g., Bellamy, L. J. (1958). The Infra-Red Spectra of Complex Molecules. New York: Wiley. p. 392. ISBN 978-0-412-13850-8.

- Spieseke, H.; Schneider, W. G. (1961). "Effect of Electronegativity and Magnetic Anisotropy of Substituents on C13 and H1 Chemical Shifts in CH3X and CH3CH2X Compounds". Journal of Chemical Physics. 35 (2): 722. Bibcode:1961JChPh..35..722S. doi:10.1063/1.1731992.

- Clasen, C. A.; Good, M. L. (1970). "Interpretation of the Moessbauer spectra of mixed-hexahalo complexes of tin(IV)". Inorganic Chemistry. 9 (4): 817–820. doi:10.1021/ic50086a025.

- Fleming, Ian (2009). Molecular orbitals and organic chemical reactions (Student ed.). Chichester, West Sussex, U.K.: Wiley. ISBN 978-0-4707-4660-8. OCLC 424555669.

- "Electropositivity," Microsoft Encarta Online Encyclopedia 2009. (Archived 2009-10-31).

Bibliography

- Jolly, William L. (1991). Modern Inorganic Chemistry (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. pp. 71–76. ISBN 978-0-07-112651-9.

- Mullay, J. (1987). Estimation of atomic and group electronegativities. Structure and Bonding. 66. pp. 1–25. doi:10.1007/BFb0029834. ISBN 978-3-540-17740-1.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Electronegativity. |

- WebElements, lists values of electronegativities by a number of different methods of calculation

- Video explaining electronegativity

- Electronegativity Chart, a summary listing of each elements electronegativity along with an interactive periodic table