Apollo 12

Apollo 12 was the sixth crewed flight in the United States Apollo program and the second to land on the Moon. It was launched on November 14, 1969, from the Kennedy Space Center, Florida, four months after Apollo 11. Commander Charles "Pete" Conrad and Apollo Lunar Module Pilot Alan L. Bean performed just over one day and seven hours of lunar surface activity while Command Module Pilot Richard F. Gordon remained in lunar orbit. The landing site for the mission was located in the southeastern portion of the Ocean of Storms.

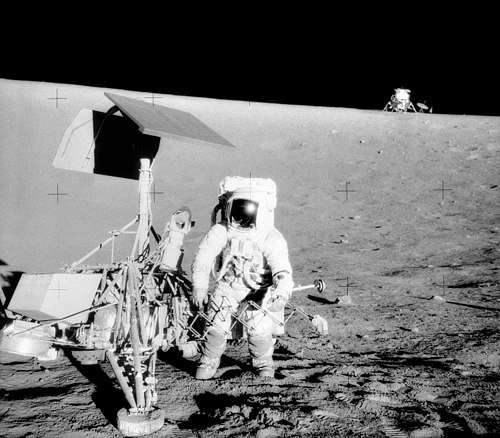

Commander Pete Conrad studies the Surveyor 3 spacecraft; the Apollo Lunar Module, Intrepid, can be seen in the top right of the picture. | |

| Mission type | Crewed lunar landing (H) |

|---|---|

| Operator | NASA[1] |

| COSPAR ID |

|

| SATCAT no. | |

| Mission duration | 10 days, 4 hours, 36 minutes, 24 seconds |

| Spacecraft properties | |

| Spacecraft |

|

| Manufacturer |

|

| Launch mass | 101,127 pounds (45,870 kg) |

| Landing mass | 11,050 pounds (5,010 kg) |

| Crew | |

| Crew size | 3 |

| Members | |

| Callsign |

|

| Start of mission | |

| Launch date | November 14, 1969, 16:22:00 UTC |

| Rocket | Saturn V SA-507 |

| Launch site | Kennedy LC-39A |

| End of mission | |

| Recovered by | USS Hornet |

| Landing date | November 24, 1969, 20:58:24 UTC |

| Landing site | South Pacific Ocean 15°47′S 165°9′W |

| Orbital parameters | |

| Reference system | Selenocentric |

| Periselene altitude | 101.10 kilometers (54.59 nmi) |

| Aposelene altitude | 122.42 kilometers (66.10 nmi) |

| Lunar orbiter | |

| Orbital insertion | November 18, 1969, 03:47:23 UTC |

| Orbital departure | November 21, 1969, 20:49:16 UTC |

| Orbits | 45 |

| Lunar lander | |

| Spacecraft component | Lunar Module (LM) |

| Landing date | November 19, 1969, 06:54:35 UTC |

| Return launch | November 20, 1969, 14:25:47 UTC |

| Landing site | Ocean of Storms 3.01239°S 23.42157°W |

| Sample mass | 34.35 kilograms (75.7 lb) |

| Surface EVAs | 2 |

| EVA duration |

|

| Docking with LM | |

| Docking date | November 14, 1969, 19:48:53 UTC |

| Undocking date | November 19, 1969, 04:16:02 UTC |

| Docking with LM ascent stage | |

| Docking date | November 20, 1969, 17:58:20 UTC |

| Undocking date | November 20, 1969, 20:21:31 UTC |

Left to right: Conrad, Gordon, Bean | |

On November 19 Conrad and Bean achieved a precise landing at their expected location within walking distance of the site of the Surveyor 3 robotic probe, which had landed on April 20, 1967. They carried the first color television camera to the lunar surface on an Apollo flight, but transmission was lost after Bean accidentally pointed the camera at the Sun and the camera's sensor was destroyed. On one of two moonwalks they visited Surveyor 3 and removed some parts for return to Earth.

Lunar Module Intrepid lifted off from the Moon on November 20 and docked with the command module, which then, after completing its 45th lunar orbit,[4] traveled back to Earth. The Apollo 12 mission ended on November 24 with a successful splashdown.

Crew

| Position | Astronaut | |

|---|---|---|

| Commander | Charles "Pete" Conrad Jr.[5] Third spaceflight | |

| Command Module Pilot | Richard F. Gordon Jr.[5] Second and last spaceflight | |

| Lunar Module Pilot | Alan L. Bean[5] First spaceflight | |

Commander Pete Conrad flew on Gemini 5 in 1965, and as command pilot on Gemini 11 in 1966. Command Module Pilot Richard F. Gordon Jr. flew with Conrad on Gemini 11. Originally, Conrad's Lunar Module pilot was Clifton C. Williams Jr., who was killed in October 1967 when the T-38 he was flying crashed near Tallahassee.[6] When forming his crew, Conrad had wanted Alan L. Bean, a former student of his at the United States Naval Test Pilot School at Patuxent River NAS, Maryland, but had been told by Director of Flight Crew Operations Deke Slayton that Bean was unavailable due to an assignment to the Apollo Applications Program. After Williams's death, Conrad asked for Bean again, and this time Slayton yielded.[7]

Backup crew

| Position | Astronaut | |

|---|---|---|

| Commander | David R. Scott[5] | |

| Command Module Pilot | Alfred M. Worden[5] | |

| Lunar Module Pilot | James B. Irwin[5] | |

| The backup crew would later fly on Apollo 15. | ||

Support crew

- Gerald P. Carr[8]

- Edward G. Gibson[8]

- Paul J. Weitz[8]

Flight directors

- Gerry Griffin, Gold team

- Pete Frank, Orange team

- Cliff Charlesworth, Green team

- Milton Windler, Maroon team

Mission parameters

- Landing Site: W[9]3.01239°S 23.42157°W

LM–CSM docking

- Undocked: November 19, 1969 – 04:16:02 UTC

- Redocked: November 20, 1969 – 17:58:20 UTC

Extravehicular Activities (EVAs)

EVA 1 start: November 19, 1969, 11:32:35 UTC

- Conrad – EVA 1

- Stepped onto Moon: 11:44:22 UTC

- LM ingress: 15:27:17 UTC

- Bean – EVA 1

- Stepped onto Moon: 12:13:50 UTC

- LM ingress: 15:14:18 UTC

EVA 1 end: November 19, 15:28:38 UTC

- Duration: 3 hours, 56 minutes, 03 seconds

EVA 2 start: November 20, 1969, 03:54:45 UTC

- Conrad – EVA 2

- Stepped onto Moon: 03:59:00 UTC

- LM ingress: 07:42:00 UTC

- Bean – EVA 2

- Stepped onto Moon: 04:06:00 UTC

- LM ingress: 07:30:00 UTC

EVA 2 end: November 20, 07:44:00 UTC

- Duration: 3 hours, 49 minutes, 15 seconds

Mission highlights

Pete Conrad descends from the lunar module. |

Alan Bean photographed by Pete Conrad (reflected in Bean's helmet) |

Launch and transfer

Apollo 12 launched on schedule from Kennedy Space Center, under completely overcast rainy skies, encountering wind speeds of 151.7 knots (280.9 km/h; 174.6 mph) during ascent, the highest of any Apollo mission.[10]

Lightning struck the Saturn V 36.5 seconds after lift-off, triggered by the vehicle itself, discharging down to the Earth through the ionized exhaust plume. Protective circuits on the fuel cells in the service module (SM) detected overloads and took all three fuel cells offline, along with much of the command and service module (CSM) instrumentation. A second strike at 52 seconds knocked out the "8-ball" attitude indicator. The telemetry stream at Mission Control was garbled. However, the Saturn V continued to fly normally; the strikes had not affected the Saturn V instrument unit guidance system, which functions independently from the CSM.

The loss of all three fuel cells put the CSM entirely on batteries, which were unable to maintain normal 75-ampere launch loads on the 28-volt DC bus. One of the AC inverters dropped offline. These power supply problems lit nearly every warning light on the control panel and caused much of the instrumentation to malfunction.

Electrical, Environmental and Consumables Manager (EECOM) John Aaron remembered the telemetry failure pattern from an earlier test when a power supply malfunctioned in the CSM signal conditioning electronics (SCE), which converted raw signals from instrumentation to standard voltages for the spacecraft instrument displays and telemetry encoders.[11]

Aaron made a call, "Flight, EECOM. Try SCE to Aux", which switched the SCE to a backup power supply. The switch was fairly obscure, and neither Flight Director Gerald Griffin, CAPCOM Gerald Carr, nor Mission Commander Pete Conrad immediately recognized it. Lunar Module Pilot Alan Bean, flying in the right seat as the spacecraft systems engineer, remembered the SCE switch from a training incident a year earlier when the same failure had been simulated. Aaron's quick thinking and Bean's memory saved what could have been an aborted mission, and earned Aaron the reputation of a "steely-eyed missile man".[12] Bean put the fuel cells back on line, and with telemetry restored, the launch continued successfully. Once in Earth parking orbit, the crew carefully checked out their spacecraft before re-igniting the S-IVB third stage for trans-lunar injection. The lightning strikes had caused no serious permanent damage.

Initially, it was feared that the lightning strike could have caused the explosive bolts that open the Command Module's parachute compartment to fire prematurely, rendering the parachutes useless which would have made safe return impossible. The decision was made not to share this with the astronauts since there was little that could be done to verify or resolve the problem if it existed. The parachutes deployed and functioned normally at the end of the mission.[13]

After LM separation, the S-IVB was intended to fly into solar orbit. The S-IVB auxiliary propulsion system was fired, and the remaining propellants vented to slow it down to fly past the Moon's trailing edge (the Apollo spacecraft always approached the Moon's leading edge). The Moon's gravity would then slingshot the stage into solar orbit. However, a small error in the state vector in the Saturn's guidance system caused the S-IVB to fly past the Moon at too high an altitude to achieve Earth escape velocity. It remained in a semi-stable Earth orbit after passing the Moon on November 18, 1969. It finally escaped Earth orbit in 1971 but was briefly recaptured in Earth orbit 31 years later. It was discovered by amateur astronomer Bill Yeung who gave it the temporary designation J002E3 before it was determined to be an artificial object.[14][15]

Moon landing

The Apollo 12 mission landed on November 19, 1969, on an area of the Ocean of Storms (Latin Oceanus Procellarum) that had been visited earlier by several robotic missions (Luna 5, Surveyor 3, and Ranger 7). The International Astronomical Union, recognizing this, christened this region Mare Cognitum (Known Sea). The Lunar coordinates of the landing site were 3.01239° S latitude, 23.42157° W longitude.[16] The landing site would thereafter be listed as Statio Cognitum on lunar maps. Conrad and Bean did not formally name their landing site, though Conrad nicknamed the intended touchdown area "Pete's Parking Lot".

The second lunar landing was an exercise in precision targeting, which would be needed for future Apollo missions. Most of the descent was automatic, with manual control assumed by Conrad during the final few hundred feet of descent. Unlike Apollo 11, where Neil Armstrong had to use the manual control to direct his lander downrange of the computer's target, which was strewn with boulders, Apollo 12 succeeded in landing at its intended target—within walking distance of the Surveyor 3 probe, which had landed on the Moon in April 1967.[17] This is the first and thus far only occasion in which humans have revisited a probe sent to land on another world.

Conrad actually landed Intrepid 580 feet (177 m) short of "Pete's Parking Lot", because it looked rougher during final approach than anticipated, and was a little under 1,180 feet (360 m) from Surveyor 3, a distance that was chosen to eliminate the possibility of lunar dust (being kicked up by Intrepid's descent engine during landing) from covering Surveyor 3.[18] But the actual touchdown point—approximately 600 feet (183 m) from Surveyor 3—did cause high velocity sandblasting of the probe. It was later determined that the sandblasting removed more dust than it delivered onto the Surveyor, because the probe was covered by a thin layer that gave it a tan hue as observed by the astronauts, and every portion of the surface exposed to the direct sandblasting was lightened back toward the original white color through the removal of lunar dust.[19]

EVAs

When Conrad, who was somewhat shorter than Neil Armstrong, stepped onto the lunar surface, his first words were "Whoopie! Man, that may have been a small one for Neil, but that's a long one for me."[17][20] This was not an off-the-cuff remark: Conrad had made a US$500 bet with reporter Oriana Fallaci he would say these words, after she had queried whether NASA had instructed Neil Armstrong what to say as he stepped onto the Moon. Conrad later said he was never able to collect the money.[21][22]

To improve the quality of television pictures from the Moon, a color camera was carried on Apollo 12 (unlike the monochrome camera on Apollo 11). Unfortunately, when Bean carried the camera to the place near the LM where it was to be set up, he inadvertently pointed it directly into the Sun, destroying the Secondary Electron Conduction (SEC) tube. Television coverage of this mission was thus terminated almost immediately.[23]

Apollo 12 successfully landed within walking distance of the Surveyor 3 probe. Conrad and Bean removed pieces of the probe to be taken back to Earth for analysis. It is claimed that the common bacterium Streptococcus mitis was found to have accidentally contaminated the spacecraft's camera prior to launch and survived dormant in this harsh environment for two and a half years.[24] However, this finding has since been disputed: see Reports of Streptococcus mitis on the Moon.

Astronauts Conrad and Bean also collected rocks and set up equipment that took measurements of the Moon's seismicity, solar wind flux and magnetic field, and relayed the measurements to Earth.[25] The instruments were part of the first complete nuclear-powered ALSEP station set up by astronauts on the Moon to relay long-term data from the lunar surface. The instruments on Apollo 11 were not as extensive or designed to operate long term. The astronauts also took photographs, although by accident Bean left several rolls of exposed film on the lunar surface. Meanwhile, Gordon, on board the Yankee Clipper in lunar orbit, took multi-spectral photographs of the surface.

The lunar plaque attached to the descent stage of Intrepid is unique in that unlike the other plaques, it (a) did not have a depiction of the Earth, and (b) it was textured differently: The other plaques had black lettering on polished stainless steel while the Apollo 12 plaque had the lettering in polished stainless steel while the background was brushed flat.

Return

.jpg)

_on_24_November_1969.jpg)

Intrepid's ascent stage was dropped (per normal procedures) after Conrad and Bean rejoined Gordon in orbit. It impacted the Moon on November 20, 1969, at 3.94°S 21.20°W. The seismometers the astronauts had left on the lunar surface registered the vibrations for more than an hour.

The crew stayed an extra day in lunar orbit taking photographs, for a total lunar surface stay of 31 and a half hours and a total time in lunar orbit of eighty-nine hours.

On the return flight to Earth after leaving lunar orbit, the crew of Apollo 12 witnessed (and photographed) a solar eclipse, though this one was of the Earth eclipsing the Sun.

Splashdown

Yankee Clipper returned to Earth on November 24, 1969, at 20:58 UTC (3:58pm EST, 10:58am HST), in the Pacific Ocean, approximately 500 nautical miles (800 km) east of American Samoa. During splashdown, a 16 mm film camera dislodged from storage and struck Bean in the forehead, rendering him briefly unconscious. He suffered a mild concussion and needed six stitches.[26] After recovery by USS Hornet, they were flown to Pago Pago International Airport in Tafuna for a reception, before being flown on a C-141 cargo plane to Honolulu.

Stunts and mementos

- Alan Bean smuggled a camera-shutter self-timer device on to the mission with the intent of taking a photograph with himself, Pete Conrad and the Surveyor 3 probe in the frame. As the timer was not part of their standard equipment, such an image would have thrown post-mission photo analysts into confusion over how the photo was taken. However, the self-timer was misplaced during the extra-vehicular activity (EVA) and the plan was never executed.[27]

- As one of the many pranks pulled during the friendly rivalry between the all-Navy prime crew and the all-Air Force backup crew, the Apollo 12 backup crew managed to insert into the astronauts' lunar checklist (attached to the wrists of Conrad's and Bean's space suits) reduced-sized pictures of Playboy Playmates, surprising Conrad and Bean when they looked through the checklist flip-book during their first EVA. The Apollo Lunar Surface Journal website contains a PDF file with the photocopies of their cuff checklists showing these photos.[28] Appearing in Conrad's checklist were Angela Dorian, Miss September 1967 (with the caption "SEEN ANY INTERESTING HILLS & VALLEYS ?") and Reagan Wilson, Miss October 1967 ("PREFERRED TETHER PARTNER," referring to a special procedure that would require the sharing of life support resources). The photos in Bean's cuff checklist were of Cynthia Myers, Miss December 1968, who was 17 years old at the time of her photoshoot[29][30] ("DON'T FORGET – DESCRIBE THE PROTUBERANCES") and Leslie Bianchini, Miss January 1969 ("SURVEY – HER ACTIVITY," in pun of Surveyor).[31][32] The backup crew who did this later flew to the Moon themselves on Apollo 15. At the back of Conrad's checklist they had also prepared two pages of complex geological terminology, added as a joke to give him the option to sound to Mission Control like he was as skilled as a professional career geologist. The third crewmember orbiting the Moon was not left out of the Playboy prank, as a November 1969 calendar featuring DeDe Lind, Miss August 1967, had been stowed in a locker that Dick Gordon found while his crewmates were on the lunar surface. In 2011, he put this calendar up for auction. Its value was estimated by RR Auction at US$12,000–15,000.[33][34] While the Command Module Pilot calendar was in full color, the lunar checklists carried black & white photocopies (although these were dramatized in From the Earth to the Moon as full color photos in the checklists).

- Artist Forrest "Frosty" Myers claims to have installed the art piece Moon Museum on "a leg of the Intrepid landing module with the help of an unnamed engineer at the Grumman Corporation after attempts to move the project forward through NASA's official channels were unsuccessful."[35]

- Alan Bean left a memento on the Moon: his silver astronaut pin.[17] This pin signified an astronaut who completed training but had not yet flown in space; he had worn it for six years. He was to get a gold astronaut pin for successfully completing the mission after the flight and felt he wouldn't need the silver pin thereafter.[17] Tossing his pin into a lunar crater extended the common tradition among military pilots to ceremonially dispose of their originally awarded flight wings.

Mission insignia

.jpg)

The Apollo 12 mission patch shows the crew's navy background; all three astronauts at the time of the mission were U.S. Navy commanders. It features a clipper ship arriving at the Moon, representing the CM Yankee Clipper. The ship trails fire, and flies the flag of the United States. The mission name APOLLO XII and the crew names are on a wide gold border, with a small blue trim. Blue and gold are traditional U.S. Navy colors. The patch has four stars on it – one each for the three astronauts who flew the mission and one for Clifton Williams, a U.S. Marine Corps aviator and astronaut who was killed on October 5, 1967, after a mechanical failure caused the controls of his T-38 trainer to stop responding, resulting in a crash. He trained with Conrad and Gordon as part of the backup crew for what would be the Apollo 9 mission, and would have been assigned as lunar module pilot for Apollo 12.[17]

Spacecraft location

The Apollo 12 command module Yankee Clipper is on display at the Virginia Air and Space Center in Hampton, Virginia.[36]

In 2002, astronomers thought they might have discovered another moon orbiting Earth, which they designated J002E3, that turned out to be the S-IVB third stage of the Apollo 12 Saturn V rocket.[37]

The Lunar Module Intrepid impacted the Moon November 20, 1969, at 22:17:17.7 UT (5:17 PM EST) 3.94°S 21.20°W.[38] In 2009, the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO) photographed the Apollo 12 landing site. The Intrepid lunar module descent stage, experiment package (ALSEP), Surveyor 3 spacecraft, and astronaut footpaths are all visible.[39] In 2011, the LRO returned to the landing site at a lower altitude to take higher resolution photographs.[40]

Orbital leftovers

The Apollo 12 third stage, an S-IVB, after passing the Moon on 18 November 1969 and not entering a Lunar orbit like the Command Module and Lunar Lander, entered an elliptical Earth orbit with a period of approximately 43 days,[41] and thus became a derelict satellite orbiting Earth. Some time later, the spent third stage entered a heliocentric orbit, but was not observed doing so. The likely mechanism was via one of the Sun-Earth Lagrangian points, which serve "as a 'portal' between the regions of space gravitationally controlled by the Earth and Sun."[41]

Notably, in April 2002, it reentered a temporary orbit around the Earth-Moon system near the Sun-Earth L1 Lagrangian point—"a location where the gravity of the Earth and Sun approximately cancel"[41]—and remained in orbital synchrony with both the Moon and the Earth for a little over a year, reentering a heliocentric orbit in May 2003. The object was "discovered" by near-Earth object watcher Bill Yeung on 3 September 2002, labeled object "J002E3" by the Minor Planet Center, and was subsequently identified as the former Apollo 12 stage only several days later. The rocket stage is "the first known case of an object being captured by the Earth, although Jupiter has been known to capture comets via the same mechanism."[41]

Depiction in media

Portions of the Apollo 12 mission are dramatized in the 1998 miniseries From the Earth to the Moon episode entitled "That's All There Is." Conrad, Gordon, and Bean were portrayed by Paul McCrane, Tom Verica, and Dave Foley, respectively. Conrad had been portrayed by a different actor, Peter Scolari, in the first episode.

See also

- Extra-vehicular activity

- Bench Crater meteorite

- Google Moon

- List of artificial objects on the Moon

- List of spacewalks and moonwalks 1965–1999

- Splashdown

References

![]()

- Orloff, Richard W. (September 2004) [First published 2000]. "Table of Contents". Apollo by the Numbers: A Statistical Reference. NASA History Division, Office of Policy and Plans. NASA History Series. Washington, D.C.: NASA. ISBN 978-0-16-050631-4. LCCN 00061677. NASA SP-2000-4029. Retrieved June 12, 2013.

- "Apollo 12 Command and Service Module (CSM)". NASA Space Science Data Coordinated Archive. Retrieved November 21, 2019.

- "Apollo 12 Lunar Module / ALSEP". NASA Space Science Data Coordinated Archive. Retrieved November 21, 2019.

- "Apollo 12 – The Sixth Mission: The Second Lunar Landing". US: NASA. Retrieved June 26, 2019.

- "Apollo 12 Crew". Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum. Retrieved December 29, 2017.

- Brooks, et al. 1979, Chapter 11.3: "Selecting and training crews"

- Chaikin, Andrew (1994). A Man on the Moon: The Voyages of the Apollo Astronauts. New York, NY: Viking. pp. 245–248. ISBN 978-0-670-81446-6. LCCN 93048680.

- Orloff, Richard W. (June 2004) [2001]. "Apollo by the Numbers: A Statistical Guide". NASA. SP-4029.

- Williams, David R. "Apollo Landing Site Coordinates". National Space Science Data Center. NASA. Retrieved November 7, 2011.

- "Launch Weather". history.nasa.gov. Retrieved June 22, 2019.

- Kranz, Eugene F.; Covington, James Otis (1971) ["A series of eight articles reprinted by permission from the March 1970 issue of Astronautics & Aeronautics, a publication of the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics."]. "Flight Control in the Apollo Program". What Made Apollo a Success?. NASA History Program Office. Washington, D.C.: NASA. OCLC 69849598. NASA SP-287. Retrieved November 7, 2011. Chapter 5.

- Kluger, Jeffrey; Lovell, James (October 1994). Lost Moon. Boston, Massachusetts: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-395-67029-3.

- Cimino, Al (May 14, 2019). Apollo : the mission to land a man on the Moon. New York, NY. p. 150. ISBN 978-0-7858-3703-9. OCLC 1056779871.

- Chodas, Paul; Chesley, Steve (October 9, 2002). "J002E3: An Update". nasa.gov. Archived from the original on May 3, 2003. Retrieved September 18, 2013.

- Jorgensen, K.; Rivkin, A.; Binzel, R.; Whitely, R.; Hergenrother, C.; Chodas, P.; Chesley, S.; Vilas, F (May 2003). "Observations of J002E3: Possible Discovery of an Apollo Rocket Body". Bulletin of the American Astronomical Society. 35: 981. Bibcode:2003DPS....35.3602J.

- "Landing Sites". The Apollo Program. National Air and Space Museum. Retrieved November 7, 2011.

- Chaikin 1995

- "1969 Year in Review: Apollo 11". UPI.com. United Press International. 1969. Retrieved November 7, 2011.

- Immer, Christopher A.; Metzger, Philip; Hintze, Paul E.; et al. (February 2011). "Apollo 12 Lunar Module Exhaust Plume Impingement on Lunar Surveyor III". Icarus. Amsterdam: Elsevier. 211 (2): 1089–1102. Bibcode:2011Icar..211.1089I. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2010.11.013.

- "Apollo 12 First Steps" on YouTube

- Chaikin 1995, p. 261

- Sawyer, Kathy (July 10, 1999). "Conrad: Pioneer of the Final Frontier". The Washington Post. p. C1. Retrieved November 7, 2011.

- Jones, Eric M., ed. (1995). "One Small Step". Apollo 11 Lunar Surface Journal. NASA. Retrieved November 7, 2011. Note at 109:57:55.

- Noever, David (September 1, 1998). "Earth Microbes on the Moon". Science@NASA. NASA. Retrieved November 7, 2011.

- "Apollo 12 Science Experiments". Lunar and Planetary Institute. Retrieved April 2, 2019.

- "Apollo 12 Mission Report" (PDF). Apollo 12 Lunar Surface Journal. NASA. March 1970. MSC-01855. Retrieved June 23, 2013.

- Bisney, John (2015). Moonshots and snapshots of Project Apollo : a rare photographic history. Pickering, J. L., 1957-. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. ISBN 978-0-8263-5260-6. OCLC 966913635.

- "Cuff Checklists" (PDF). Apollo 12 Lunar Surface Journal. NASA. Retrieved November 7, 2011.

- "Cynthia Myers Bio Playboy's Miss December 1968". Archived from the original on June 18, 2001.

- Waage, Randy (2006). "Cynthia Myers interview". retroCRUSH. Archived from the original on August 8, 2008. Retrieved May 4, 2018.

- Jardin, Xeni (January 13, 2007). "Playboy Playmates pranked into Apollo 12 mission checklists". Boing Boing. Archived from the original on May 17, 2011. Retrieved November 7, 2011.

- Rowe, Chip (January 10, 2007). "On Buckeyes, Nanotechnology and Playmates in Space". The Playboy Blog. Playboy Enterprises. Archived from the original on March 17, 2007. Retrieved November 7, 2011.

- "NASA Memorabilia Auction". Alternative Investing. CNBC. Archived from the original on October 15, 2012. Retrieved November 7, 2011.

- "Playmate Flashback: DeDe Lind Circles the Moon". Playmate of the Year. Playboy Enterprises. January 4, 2011. Archived from the original on August 24, 2011. Retrieved November 7, 2011.

- Allen, Greg (February 28, 2008). "The Moon Museum". greg.org: the making of. greg.org. Retrieved November 7, 2011.

- "Location of Apollo Command Modules". Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum. Retrieved August 27, 2019.

- Cain, Fraser (June 12, 2008). "How Many Moons Does Earth Have?". Universe Today. Retrieved November 7, 2011.

- "Impact Sites of Apollo LM Ascent and SIVB Stages". NASA Space Science Data Coordinated Archive. Retrieved August 27, 2019.

- Garner, Robert, ed. (September 3, 2009). "Apollo 12 and Surveyor 3". NASA. Retrieved November 7, 2011.

- Neal-Jones, Nancy; Zubritsky, Elizabeth; Cole, Steve (September 6, 2011). Garner, Robert (ed.). "NASA Spacecraft Images Offer Sharper Views of Apollo Landing Sites". NASA. Goddard Release No. 11-058 (co-issued as NASA HQ Release No. 11-289). Retrieved November 7, 2011.

- "Newly Discovered Object Could be a Leftover Apollo Rocket Stage". Center for Near-Earth Object Studies. California Institute of Technology, Jet Propulsion Laboratory. September 11, 2002.

Bibliography

- Chaikin, Andrew (1995). A Man on the Moon: The Voyages of the Apollo Astronauts. Foreword by Tom Hanks. New York: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-024146-4.

- Lattimer, Dick (1985). All We Did Was Fly to the Moon. History-alive series. 1. Foreword by James A. Michener (1st ed.). Alachua, FL: Whispering Eagle Press. ISBN 978-0-9611228-0-5.

- Lovell, Jim; Kluger, Jeffrey (1994). Lost Moon: The Perilous Voyage of Apollo 13. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-395-67029-3.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Apollo 12. |

- "Apollo 12" at Encyclopedia Astronautica

- "Apollo 12" at NASA's National Space Science Data Center

- "Apollo 12 Traverse Map" at the USGS Astrogeology Science Center

- Lunar Orbiter 3 Image 154 H2, used for planning the mission (landing site is left of center).

NASA reports

- "Apollo 12 Mission Report" (PDF), NASA, MSC-01855, March 1970

- "Apollo 12 Preliminary Science Report" (PDF), NASA, NASA SP-235, 1970

- NASA Apollo 12 Press Kit (PDF), NASA, Release No. 69-148, November 5, 1969

- "Analysis of Apollo 12 Lightning Incident", (PDF) February 1970

- "Analysis of Surveyor 3 material and photographs returned by Apollo 12" (PDF) 1972

- "Examination of Surveyor 3 surface sampler scoop returned by Apollo 12 mission"(PDF) 1971

- "Table 2-40. Apollo 12 Characteristics" from NASA Historical Data Book: Volume III: Programs and Projects 1969–1978 by Linda Neuman Ezell, NASA History Series (1988)

- The Apollo Spacecraft: A Chronology NASA, NASA SP-4009

- "Apollo Program Summary Report" (PDF), NASA, JSC-09423, April 1975

Multimedia

- The short film Apollo 12: Pinpoint For Science is available for free download at the Internet Archive

- "Apollo 12: Pinpoint For Science" on YouTube

- "Apollo 12: The Bernie Scrivener Audio Tapes" – Apollo 12 audio recordings at the Apollo 12 Flight Journal

- "Apollo 12: There and Back Again" – Image slideshow by Life magazine

- "Apollo12: Comic Book" (50th Anniversary - November 20, 1969-2019)

- "Apollo 12: Patch" – Image of Apollo 12 mission patch