Tibolone

Tibolone, sold under the brand names Livial, Tinox and Tibofem among others, is a medication which is used in menopausal hormone therapy and in the treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis and endometriosis.[1][7][8][9] The medication is available alone and is not formulated or used in combination with other medications.[10] It is taken by mouth.[1]

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Livial, Tibofem, others |

| Other names | TIB; ORG-OD-14; 7α-Methylnoretynodrel; 7α-Methyl-17α-ethynyl-19-nor-δ5(10)-testosterone; 17α-Ethynyl-7α-methylestr-5(10)-en-17β-ol-3-one; 7α-Methyl-19-nor-17α-pregn-5(10)-en-20-yn-17-ol-3-one |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | International Drug Names |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | By mouth[1] |

| Drug class | Progestogen; Progestin; Estrogen; Androgen; Anabolic steroid |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 92%[3] |

| Protein binding | 96.3% (to albumin; low affinity for SHBG)[3] |

| Metabolism | Liver, intestines (hydroxyl-ation, isomerization, conjugation)[1][4] |

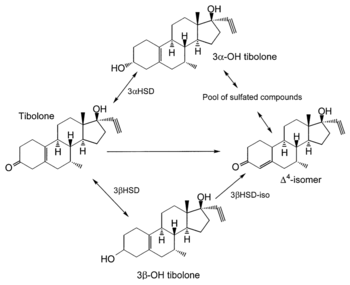

| Metabolites | • Δ4-Tibolone[5] • 3α-Hydroxytibolone[5] • 3β-Hydroxytibolone[5] • Sulfate conjugates[6] |

| Elimination half-life | 45 hours[4] |

| Excretion | Urine: 40%[3] Feces: 60%[3] |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.024.609 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C21H28O2 |

| Molar mass | 312.453 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Side effects of tibolone include acne and increased hair growth among others.[4] Tibolone is a synthetic steroid with weak estrogenic, progestogenic, and androgenic activity, and hence is an agonist of the estrogen, progesterone, and androgen receptors.[11][1][4][5] It is a prodrug of several metabolites.[1][11][12] The estrogenic effects of tibolone may show tissue selectivity in their distribution.[11][13][12][14]

Tibolone was developed in the 1960s and was introduced for medical use in 1988.[15][16] It is marketed widely throughout the world, for instance in Europe.[10][17] The medication is notably not available in the United States or Canada.[10][17] It is a controlled substance in Canada, with the classification of an anabolic steroid.[2]

Medical uses

Tibolone is used in the treatment of menopausal symptoms like hot flashes and vaginal atrophy, postmenopausal osteoporosis, and endometriosis.[1][18][9] It has similar or greater effectiveness compared to older menopausal hormone therapy medications, but shares a similar side effect profile.[19][20][21] It has also been investigated as a possible treatment for female sexual dysfunction.[22]

Tibolone reduces hot flashes, prevents bone loss, improves vaginal atrophy and urogenital symptoms (e.g., vaginal dryness, dyspareunia), and has positive effects on mood and sexual function.[23][20][24] The medication may have greater benefits on libido than standard menopausal hormone therapy, which may be related to its androgenic effects.[20][24] It is associated with low rates of vaginal bleeding and breast pain.[23]

A 2015 network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials found that tibolone was associated with a significantly decreased risk of breast cancer (RR = 0.317).[25] The decrease in risk was greater than that observed with most of the aromatase inhibitors and selective estrogen receptor modulators that were included in the analysis.[25] However, paradoxically, other research has found evidence supporting an increased risk of breast cancer with tibolone.[26][27]

| Route | Medication | Major brand names | Form | Dosage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oral | Testosterone undecanoate | Andriol, Jatenzo | Capsule | 40–80 mg 1x/1–2 days |

| Methyltestosterone | Metandren, Estratest | Tablet | 0.5–10 mg/day | |

| Fluoxymesterone | Halotestin | Tablet | 1–2.5 mg 1x/1–2 days | |

| Normethandronea | Ginecoside | Tablet | 5 mg/day | |

| Tibolone | Livial | Tablet | 1.25–2.5 mg/day | |

| Prasterone (DHEA)b | – | Tablet | 10–100 mg/day | |

| Sublingual | Methyltestosterone | Metandren | Tablet | 0.25 mg/day |

| Transdermal | Testosterone | Intrinsa | Patch | 150–300 μg/day |

| AndroGel | Gel, cream | 1–10 mg/day | ||

| Vaginal | Prasterone (DHEA) | Intrarosa | Insert | 6.5 mg/day |

| Injection | Testosterone propionatea | Testoviron | Oil solution | 25 mg 1x/1–2 weeks |

| Testosterone enanthate | Delatestryl, Primodian Depot | Oil solution | 25–100 mg 1x/4–6 weeks | |

| Testosterone cypionate | Depo-Testosterone, Depo-Testadiol | Oil solution | 25–100 mg 1x/4–6 weeks | |

| Testosterone isobutyratea | Femandren M, Folivirin | Aqueous suspension | 25–50 mg 1x/4–6 weeks | |

| Mixed testosterone esters | Climacterona | Oil solution | 150 mg 1x/4–8 weeks | |

| Omnadren, Sustanon | Oil solution | 50–100 mg 1x/4–6 weeks | ||

| Nandrolone decanoate | Deca-Durabolin | Oil solution | 25–50 mg 1x/6–12 weeks | |

| Prasterone enanthatea | Gynodian Depot | Oil solution | 200 mg 1x/4–6 weeks | |

| Implant | Testosterone | Testopel | Pellet | 50–100 mg 1x/3–6 months |

| Notes: Premenopausal women produce about 230 ± 70 μg testosterone per day (6.4 ± 2.0 mg testosterone per 4 weeks), with a range of 130 to 330 μg per day (3.6–9.2 mg per 4 weeks). Footnotes: a = Mostly discontinued or unavailable. b = Over-the-counter. Sources: See template. | ||||

Side effects

A report in September 2009 from Health and Human Services' Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality suggests that tamoxifen, raloxifene, and tibolone used to reduce the risk of breast cancer significantly reduce the occurrence of invasive breast cancer in midlife and older women, but also increase the risk of adverse effects.[29]

Tibolone can infrequently produce androgenic side effects such as acne and increased facial hair growth.[4] Such side effects have been found to occur in 3 to 6% of treated women.[4]

A 2016 Cochrane review has been published on the short-term and long-term effects of tibolone, including adverse effects.[30] Possible adverse effects of tibolone include unscheduled vaginal bleeding (OR = 2.79; incidence 13–26% more than placebo), an increased risk of breast cancer in women with a history of breast cancer (OR = 1.5) although apparently not without a history of breast cancer (OR = 0.52), an increased risk of cerebrovascular events (strokes) (OR = 1.74) and cardiovascular events (OR = 1.38), and an increased risk of endometrial cancer (OR = 2.04).[30] However, most of these figures are based on very low-quality evidence.[30]

Tibolone has been associated with increased risk of endometrial cancer in most studies.[31]

Pharmacology

Pharmacodynamics

Tibolone possesses a complex pharmacology and has weak estrogenic, progestogenic, and androgenic activity.[4][1][5] Tibolone, 3α-hydroxytibolone, and 3β-hydroxytibolone act as agonists of the estrogen receptors.[1][5] Tibolone and its metabolite δ4-tibolone act as agonists of the progesterone and androgen receptors,[32] while 3α-hydroxytibolone and 3β-hydroxytibolone, conversely, act as antagonists of these receptors.[5] Relative to other progestins, tibolone, including its metabolites, has been described as possessing moderate functional antiestrogenic activity (that is, progestogenic activity), moderate estrogenic activity, high androgenic activity, and no clinically significant glucocorticoid, antiglucocorticoid, mineralocorticoid, or antimineralocorticoid activity.[1][33] The ovulation-inhibiting dosage of tibolone is 2.5 mg/day.[1]

| Compound | Code name | PR | AR | ER | GR | MR | SHBG | CBG |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Noretynodrel | – | 6 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Norethisterone (δ4-NYD) | – | 67–75 | 15 | 0 | 0–1 | 0–3 | 16 | 0 |

| 3α-Hydroxynoretynodrel | – | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? |

| 3β-Hydroxynoretynodrel | – | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? |

| Ethinylestradiol | – | 15–25 | 1–3 | 112 | 1–3 | <1 | 0.18 | <0.1 |

| Tibolone (7α-Me-NYD) | ORG-OD-14 | 6 | 6 | 1 | ? | ? | ? | ? |

| Δ4-Tibolone | ORG-OM-38 | 90 | 35 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| 3α-Hydroxytibolone | ORG-4094 | 0 | 3 | 4–6 | 0 | ? | ? | ? |

| 3β-Hydroxytibolone | ORG-301260 | 0 | 4 | 3–29 | 0 | ? | ? | ? |

| 7α-Methylethinylestradiol | – | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? |

| Notes: Values are percentages (%). Reference ligands (100%) were promegestone for the PR, metribolone for the AR, E2 for the ER, DEXA for the GR, aldosterone for the MR, DHT for SHBG, and cortisol for CBG. Sources: See template. | ||||||||

| Compound | Code name | PR | AR | ERα | ERβ | GR | MR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tibolone | ORG-OD-14 | 123 | 1.05 | 4 | 105 | 2410* | 170* |

| Δ4-Tibolone | ORG-OM-38 | 46 | 0.2 | 26 | 300 | 1760* | 30* |

| 3α-Hydroxytibolone | ORG-4094 | 2400* | 135* | 1.7 | 100 | ND* | 1160* |

| 3β-Hydroxytibolone | ORG-30126 | 20000* | ND* | 2.4 | 115 | ND* | 3310* |

| Notes: Values are affinities (nM). Non-italicized values are EC50. Italicized values with an asterisk (*) are IC50. Reference ligands (EC50) were promegestone (5 nM for PR), metribolone (0.1 nM for AR), estradiol (0.018 nM for ERα, 0.08 nM for ERβ), dexamethasone (6 nM for GR), and aldosterone (0.36 nM for MR). Sources: See template. | |||||||

Estrogenic activity

Tibolone and its two major active metabolites, 3α-hydroxytibolone and 3β-hydroxytibolone, act as potent, fully activating agonists of the estrogen receptor (ER), with a high preference for the ERα.[5][32][13] These estrogenic metabolites of tibolone have much weaker activity as estrogens than estradiol (e.g., have 3–29% of the affinity of estradiol for the ER), but occur at relatively high concentrations that are sufficient for full and marked estrogenic responses to occur.[1][13][34]

The estrogenic effects of tibolone show tissue selectivity in their distribution, with desirable effects in bone, the brain, and the vagina, and lack of undesirable action in the uterus, breast, and liver.[13][11][12] The observations of tissue selectivity with tibolone have been theorized to be the result of metabolism, enzyme modulation (e.g., of estrogen sulfatase and estrogen sulfotransferase), and receptor modulation that vary in different target tissues.[32][13] This selectivity differs mechanistically from that of selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) such as tamoxifen, which produce their tissue selectivity via means of modulation of the ER.[32][13] As such, to distinguish it from SERMs, tibolone has been variously described as a "selective tissue estrogenic activity regulator" (STEAR),[13] "selective estrogen enzyme modulator" (SEEM),[14] or "tissue-specific receptor and intracrine mediator" (TRIM).[33] More encompassingly, tibolone has also been described as a "selective progestogen, estrogen, and androgen regulator" (SPEAR), which is meant to reflect the fact that it is tissue-selective and that it regulates effects not only of estrogens but of all three of the major sex hormone classes.[33] Although indications of tissue selectivity with tibolone have been observed, the medication has paradoxically nonetheless been associated with increased risk of endometrial cancer and breast cancer in clinical studies.[30]

It was reported in 2002 that tibolone or its metabolite δ4-tibolone is transformed by aromatase into the potent estrogen 7α-methylethinylestradiol in women, analogously to the transformation of norethisterone into ethinylestradiol.[35] Controversy and disagreement followed when other researchers contested the findings however.[36][37][38][39][40][41] By 2008, these researchers had asserted that tibolone is not aromatized in women and that the previous findings of 7α-methylethinylestradiol detection were merely a methodological artifact.[38][40][41] In accordance, a 2009 study found that an aromatase inhibitor had no effect on the estrogenic potencies of tibolone or its metabolites in vitro, unlike the case of testosterone.[5] In addition, another 2009 study found that the estrogenic effects of tibolone on adiposity in rats do not require aromatization (as indicated by the use of aromatase knockout mice), further in support that 3α-hydroxytibolone and 3β-hydroxytibolone are indeed responsible for such effects.[42] These findings are also in accordance with the fact that tibolone decreases sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG) levels by 50% in women and does not increase the risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE) (RR = 0.92), which would not be expected if the medication formed a potent, liver metabolism-resistant estrogen similar to ethinylestradiol in important quantities.[1][43] (For comparison, combined oral contraceptives containing ethinylestradiol, due mostly or completely to the estrogen component, have been found to increase SHBG levels by 200 to 400% and to increase the risk of VTE by about 4-fold (OR = 4.03).)[44][45]

In spite of the preceding, others have held, as recently as 2011, that tibolone is converted into 7α-methylethinylestradiol in small quantities.[46][47] They have claimed that 19-nortestosterone derivatives like tibolone, due to lacking a C19 methyl group, indeed are not substrates of the classical aromatase enzyme, but instead are still transformed into the corresponding estrogens by other cytochrome P450 monooxygenases.[39][46][47] In accordance, the closely structurally related AAS trestolone (7α-methyl-19-nortestosterone or 17α-desethynyl-δ4-tibolone) has been found to be transformed into 7α-methylestradiol by human placental microsomes in vitro.[41][48] Also in accordance, considerably disproportionate formation of ethinylestradiol occurs when norethisterone is taken orally (and hence undergoes first-pass metabolism in the liver) relative to parenterally,[49][50] despite the absence of aromatase in the adult human liver.[47][51]

Progestogenic activity

Tibolone and δ4-tibolone act as agonists of the progesterone receptor (PR).[1][47][52] Tibolone has low affinity of 6% of that of promegestone for the PR, while δ4-tibolone has high affinity of 90% of that of promegestone for the PR.[1][47] In spite of its high affinity for the PR however, δ4-tibolone possesses only weak progestogenic activity, about 13% of that of norethisterone.[1][47] The weak progestogenic activity of tibolone may not be sufficient to fully counteract estrogenic activity of tibolone in the uterus and may be responsible for the increased risk of endometrial cancer that has been observed with tibolone in women in large cohort studies.[1][47]

Androgenic activity

Tibolone, mainly via δ4-tibolone, has androgenic activity.[47][1] Whereas tibolone itself has only about 6% of the affinity of metribolone for the androgen receptor, δ4-tibolone has relatively high affinity of about 35% of the affinity of metribolone for this receptor.[47][1] At typical clinical dosages in women, the androgenic effects of tibolone are weak.[47][1] However, relative to other 19-nortestosterone progestins, the androgenic activity of tibolone is high, with a potency comparable to that of testosterone.[47][1] Indeed, the androgenic effects of tibolone have been ranked as stronger than those of all other commonly used 19-nortestosterone progestins (e.g., norethisterone, levonorgestrel, others).[47][1]

The androgenic effects of tibolone have been postulated to be involved in the reduced breast cell proliferation, reduced breast cancer risk, improvement in sexual function, less unfavorable changes in hemostatic parameters relative to estrogen–progestogen combinations, and changes in liver protein synthesis (e.g., 30% reductions in HDL cholesterol levels, 20% reduction in triglyceride levels, and 50% reduction in SHBG levels) observed with tibolone.[47][1] They are also responsible for the androgenic side effects of tibolone such as acne and increased hair growth in some women.[4]

Other activities

Tibolone, 3α-hydroxytibolone, and 3β-hydroxytibolone act as antagonists of the glucocorticoid and mineralocorticoid receptors, with preference for the mineralocorticoid receptor.[5] However, their affinities for these receptors are low, and tibolone has been described as possessing no clinically significant glucocorticoid, antiglucocorticoid, mineralocorticoid, or antimineralocorticoid activity.[1][33]

Pharmacokinetics

The mean oral bioavailability of tibolone is 92%.[3] Its plasma protein binding is 96.3%.[3] It is bound to albumin, and both tibolone and its metabolites have low affinity for SHBG.[3][1] Tibolone is metabolized in the liver and intestines.[1][4] It is a prodrug and is rapidly transformed into several metabolites, including δ4-tibolone, 3α-hydroxytibolone, and 3β-hydroxytibolone, as well as sulfate conjugates of these metabolites.[1][52][6] 3α-Hydroxytibolone is formed by 3α-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase, 3β-hydroxytibolone is formed by 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase, δ4-tibolone is formed by Δ5-4-isomerase, and the sulfate conjugates of tibolone and its metabolites are formed by sulfotransferases, mainly SULT2A1.[33] [53] The sulfate conjugates can be transformed back into free steroids by steroid sulfatase.[54] Following a single oral dose of 2.5 mg tibolone, peak serum levels of tibolone were 1.6 ng/mL, of δ4-tibolone were 0.8 ng/mL, of 3α-hydroxytibolone were 16.7 ng/mL, and of 3β-hydroxytibolone were 3.7 ng/mL after 1 to 2 hours.[1] The elimination half-life of tibolone is 45 hours.[4] It is excreted in urine 40% and feces 60%.[3][4]

Chemistry

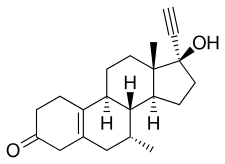

Tibolone, also known as 7α-methylnoretynodrel, as well as 7α-methyl-17α-ethynyl-19-nor-δ5(10)-testosterone or as 7α-methyl-17α-ethynylestr-5(10)-en-17β-ol-3-one, is a synthetic estrane steroid and a derivative of testosterone and 19-nortestosterone.[7][1] It is more specifically a derivative of norethisterone (17α-ethynyl-19-nortestosterone) and is a member of the estrane subgroup of the 19-nortestosterone family of progestins.[1][55][56][15] Tibolone is the 7α-methyl derivative of the progestin noretynodrel (17α-ethynyl-δ5(10)-19-nortestosterone).[1] Other steroids related to tibolone include the progestin norgesterone (17α-vinyl-δ5(10)-19-nortestosterone) and the anabolic steroids trestolone (7α-methyl-19-nortestosterone) and mibolerone (7α,17α-dimethyl-19-nortestosterone).[7]

History

Tibolone was developed in the 1960s.[15] It was first introduced in the Netherlands in 1988, and was subsequently introduced in the United Kingdom in 1991.[16][57]

Society and culture

Generic names

Tibolone is the generic name of the drug and its INN, USAN, BAN, DCF, and JAN.[7][8] It is also known by its developmental code name ORG-OD-14.[4]

Brand names

Tibolone is marketed under the brand names Livial, Tibofem, and Ladybon among others.[7][8][10]

Availability

Tibolone and is used widely in Europe, Asia, Australasia, and elsewhere in the world, but is notably not available in the United States or Canada.[10][17][58]

Legal status

Tibolone is a Schedule IV controlled substance in Canada under the 1996 Controlled Drugs and Substances Act.[2] It is classified as an anabolic steroid under this act, due to its relatively high activity as an AR agonist, and is the only norethisterone (17α-ethynyl-19-nortestosterone) derivative that is classified as such.[2]

References

- Kuhl H (2005). "Pharmacology of estrogens and progestogens: influence of different routes of administration" (PDF). Climacteric. 8 Suppl 1: 3–63. doi:10.1080/13697130500148875. PMID 16112947.

- "Controlled Drugs and Substances Act (S.C. 1996, c. 19)". 2016-11-30.

- "Tibolone 2.5 mg Tablets" (PDF). Public Assessment Report. United Kingdom Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA).

- Albertazzi P, Di Micco R, Zanardi E (1998). "Tibolone: a review". Maturitas. 30 (3): 295–305. doi:10.1016/S0378-5122(98)00059-0. PMID 9881330.

- Escande A, Servant N, Rabenoelina F, Auzou G, Kloosterboer H, Cavaillès V, Balaguer P, Maudelonde T (2009). "Regulation of activities of steroid hormone receptors by tibolone and its primary metabolites". J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 116 (1–2): 8–14. doi:10.1016/j.jsbmb.2009.03.008. PMID 19464167.

- Falany JL, Macrina N, Falany CN (April 2004). "Sulfation of tibolone and tibolone metabolites by expressed human cytosolic sulfotransferases". J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 88 (4–5): 383–91. doi:10.1016/j.jsbmb.2004.01.005. PMID 15145448.

- Ganellin C, Triggle DJ (21 November 1996). Dictionary of Pharmacological Agents. CRC Press. pp. 1974–. ISBN 978-0-412-46630-4.

- Morton I, Hall JM (6 December 2012). Concise Dictionary of Pharmacological Agents: Properties and Synonyms. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 275–. ISBN 978-94-011-4439-1.

- "Tibolone". AdisInsight.

- "Tibolone". Drugs.com.

- Cano A (2 November 2017). Menopause: A Comprehensive Approach. Springer. pp. 103–. ISBN 978-3-319-59318-0.

- Falcone T, Hurd WW (14 June 2017). Clinical Reproductive Medicine and Surgery: A Practical Guide. Springer. pp. 182–. ISBN 978-3-319-52210-4.

- Schneider HP, Naftolin F (22 September 2004). Climacteric Medicine - Where Do We Go?: Proceedings of the 4th Workshop of the International Menopause Society. CRC Press. pp. 126–. ISBN 978-0-203-02496-6.

- King T, Brucker MC (25 October 2010). Pharmacology for Women's Health. Jones & Bartlett Learning. pp. 371–. ISBN 978-0-7637-5329-0.

- Fritz MA, Speroff L (28 March 2012). Clinical Gynecologic Endocrinology and Infertility. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 769–. ISBN 978-1-4511-4847-3.

- de Vries CS, Bromley SE, Thomas H, Farmer RD (2005). "Tibolone and endometrial cancer: a cohort and nested case-control study in the UK". Drug Safety. 28 (3): 241–9. doi:10.2165/00002018-200528030-00005. PMID 15733028.

- Segal SJ, Mastroianni L (4 October 2003). Hormone Use in Menopause and Male Andropause : A Choice for Women and Men: A Choice for Women and Men. Oxford University Press, USA. pp. 73–. ISBN 978-0-19-803620-3.

- Al Kadri H, Hassan S, Al-Fozan HM, Hajeer A (January 2009). Al Kadri H (ed.). "Hormone therapy for endometriosis and surgical menopause". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (1): CD005997. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005997.pub2. PMID 19160262.

- Lazovic G, Radivojevic U, Marinkovic J (April 2008). "Tibolone: the way to beat many a postmenopausal ailments". Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy. 9 (6): 1039–47. doi:10.1517/14656566.9.6.1039. PMID 18377345.

- Garefalakis M, Hickey M (2008). "Role of androgens, progestins and tibolone in the treatment of menopausal symptoms: a review of the clinical evidence". Clin Interv Aging. 3 (1): 1–8. doi:10.2147/CIA.S1043. PMC 2544356. PMID 18488873.

- Vavilis D, Zafrakas M, Goulis DG, Pantazis K, Agorastos T, Bontis JN (2009). "Hormone therapy for postmenopausal breast cancer survivors: a survey among obstetrician-gynaecologists". European Journal of Gynaecological Oncology. 30 (1): 82–4. PMID 19317264.

- Ziaei S, Moghasemi M, Faghihzadeh S (April 2010). "Comparative effects of conventional hormone replacement therapy and tibolone on climacteric symptoms and sexual dysfunction in postmenopausal women". Climacteric. 13 (2): 147–56. doi:10.1080/13697130903009195. PMID 19731119.

- Kenemans P, Speroff L (May 2005). "Tibolone: clinical recommendations and practical guidelines. A report of the International Tibolone Consensus Group". Maturitas. 51 (1): 21–8. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2005.02.011. PMID 15883105.

- Davis SR (2002). "The effects of tibolone on mood and libido". Menopause. 9 (3): 162–70. doi:10.1097/00042192-200205000-00004. PMID 11973439.

- Mocellin S, Pilati P, Briarava M, Nitti D (February 2016). "Breast Cancer Chemoprevention: A Network Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials". J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 108 (2). doi:10.1093/jnci/djv318. PMID 26582062.

- Erel CT, Senturk LM, Kaleli S (October 2006). "Tibolone and breast cancer". Postgrad Med J. 82 (972): 658–62. doi:10.1136/pgmj.2005.037184. PMC 2653908. PMID 17068276.

- Wang PH, Cheng MH, Chao HT, Chao KC (June 2007). "Effects of tibolone on the breast of postmenopausal women". Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 46 (2): 121–6. doi:10.1016/S1028-4559(07)60005-9. PMID 17638619.

- Meeta (15 December 2013). Postmenopausal Osteoporosis: Basic and Clinical Concepts. Jaypee Brothers Publishers. pp. 117–. ISBN 978-93-5090-833-4.

- "Medications Effective in Reducing Risk of Breast Cancer But Increase Risk of Adverse Effects, New Report Says". U.S. Department of Health & Human Services - Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. September 2009. Retrieved 2 June 2014.

- Formoso, Giulio; Perrone, Enrica; Maltoni, Susanna; Balduzzi, Sara; Wilkinson, Jack; Basevi, Vittorio; Marata, Anna Maria; Magrini, Nicola; D'Amico, Roberto; Bassi, Chiara; Maestri, Emilio (2016-10-12). "Short-term and long-term effects of tibolone in postmenopausal women". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 10: CD008536. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008536.pub3. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 6458045. PMID 27733017.

- Sjögren LL, Mørch LS, Løkkegaard E (September 2016). "Hormone replacement therapy and the risk of endometrial cancer: A systematic review". Maturitas. 91: 25–35. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2016.05.013. PMID 27451318.

- Falcone T, Hurd WW (22 May 2013). Clinical Reproductive Medicine and Surgery: A Practical Guide. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 152–. ISBN 978-1-4614-6837-0.

- Purdie DW (September 2002). "What is tibolone--and is it a SPEAR?". Climacteric. 5 (3): 236–9. doi:10.1080/cmt.5.3.236.239. PMID 12419081.

- Schoonen WG, Deckers GH, de Gooijer ME, de Ries R, Kloosterboer HJ (2000). "Hormonal properties of norethisterone, 7α-methyl-norethisterone and their derivatives". J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 74 (4): 213–22. doi:10.1016/s0960-0760(00)00125-4. PMID 11162927.

- Wiegratz I, Sänger N, Kuhl H (2002). "Formation of 7 alpha-methyl-ethinyl estradiol during treatment with tibolone". Menopause. 9 (4): 293–5. doi:10.1097/00042192-200207000-00011. PMID 12082366.

- de Gooyer ME, Oppers-Tiemissen HM, Leysen D, Verheul HA, Kloosterboer HJ (2003). "Tibolone is not converted by human aromatase to 7alpha-methyl-17alpha-ethynylestradiol (7alpha-MEE): analyses with sensitive bioassays for estrogens and androgens and with LC-MSMS". Steroids. 68 (3): 235–43. doi:10.1016/S0039-128X(02)00184-8. PMID 12628686.

- Raobaikady B, Parsons MF, Reed MJ, Purohit A (2006). "Lack of aromatisation of the 3-keto-4-ene metabolite of tibolone to an estrogenic derivative". Steroids. 71 (7): 639–46. doi:10.1016/j.steroids.2006.03.006. PMID 16712888.

- Zacharia LC, Jackson EK, Kloosterboer HJ, Imthurn B, Dubey RK (2006). "Conversion of tibolone to 7alpha-methyl-ethinyl estradiol using gas chromatography-mass spectrometry and liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry: interpretation and clinical implications". Menopause. 13 (6): 926–34. doi:10.1097/01.gme.0000227331.49081.d7. PMID 17006378.

- Kuhl H, Wiegratz I (2007). "Can 19-nortestosterone derivatives be aromatized in the liver of adult humans? Are there clinical implications?". Climacteric. 10 (4): 344–53. doi:10.1080/13697130701380434. PMID 17653961.

- Dröge MJ, Oostebring F, Oosting E, Verheul HA, Kloosterboer HJ (2007). "7alpha-Methyl-ethinyl estradiol is not a metabolite of tibolone but a chemical stress artifact". Menopause. 14 (3 Pt 1): 474–80. doi:10.1097/01.gme.0000247015.63877.d4. PMID 17237734.

- Kloosterboer HJ (2008). "Tibolone is not aromatized in postmenopausal women". Climacteric. 11 (2): 175, author reply 175–6. doi:10.1080/13697130701752087. PMID 18365860.

- Van Sinderen ML, Boon WC, Ederveen AG, Kloosterboer HJ, Simpson ER, Jones ME (2009). "The estrogenic component of tibolone reduces adiposity in female aromatase knockout mice". Menopause. 16 (3): 582–8. doi:10.1097/gme.0b013e31818fb20b. PMID 19182696.

- Renoux C, Dell'Aniello S, Suissa S (May 2010). "Hormone replacement therapy and the risk of venous thromboembolism: a population-based study". J. Thromb. Haemost. 8 (5): 979–86. doi:10.1111/j.1538-7836.2010.03839.x. PMID 20230416.

- IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans; World Health Organization; International Agency for Research on Cancer (2007). Combined Estrogen-progestogen Contraceptives and Combined Estrogen-progestogen Menopausal Therapy. World Health Organization. pp. 157–. ISBN 978-92-832-1291-1.

- Heit JA, Spencer FA, White RH (2016). "The epidemiology of venous thromboembolism". J. Thromb. Thrombolysis. 41 (1): 3–14. doi:10.1007/s11239-015-1311-6. PMC 4715842. PMID 26780736.

- Kuhl H, Wiegratz I (2007). "In vivo conversion of TIB to MEE not an artifact generated by heat". Menopause. 14 (2): 331–4, author reply 334–5. doi:10.1097/01.gme.0000264447.18842.da. PMID 17496790.

- Kuhl H (2011). "Pharmacology of progestogens" (PDF). Journal für Reproduktionsmedizin und Endokrinologie-Journal of Reproductive Medicine and Endocrinology. 8 (Special Issue 1): 157–176.

- LaMorte A, Kumar N, Bardin CW, Sundaram K (February 1994). "Aromatization of 7 alpha-methyl-19-nortestosterone by human placental microsomes in vitro". J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 48 (2–3): 297–304. doi:10.1016/0960-0760(94)90160-0. PMID 8142308.

- Kuhnz W, Heuner A, Hümpel M, Seifert W, Michaelis K (December 1997). "In vivo conversion of norethisterone and norethisterone acetate to ethinyl etradiol in postmenopausal women". Contraception. 56 (6): 379–85. doi:10.1016/S0010-7824(97)00174-1. PMID 9494772.

- Friedrich C, Berse M, Klein S, Rohde B, Höchel J (June 2018). "In Vivo Formation of Ethinylestradiol After Intramuscular Administration of Norethisterone Enantate". J Clin Pharmacol. 58 (6): 781–789. doi:10.1002/jcph.1079. PMID 29522253.

- Hata S, Miki Y, Saito R, Ishida K, Watanabe M, Sasano H (June 2013). "Aromatase in human liver and its diseases". Cancer Med. 2 (3): 305–15. doi:10.1002/cam4.85. PMC 3699842. PMID 23930207.

- Verhoeven CH, Vos RM, Delbressine LP (2002). "The in vivo metabolism of tibolone in animal species". Eur J Drug Metab Pharmacokinet. 27 (1): 1–10. doi:10.1007/BF03190399. PMID 11996321.

- Wang M, Ebmeier CC, Olin JR, Anderson RJ (May 2006). "Sulfation of tibolone metabolites by human postmenopausal liver and small intestinal sulfotransferases (SULTs)". Steroids. 71 (5): 343–51. doi:10.1016/j.steroids.2005.11.003. PMID 16360722.

- Falany JL, Falany CN (2007). "Interactions of the human cytosolic sulfotransferases and steroid sulfatase in the metabolism of tibolone and raloxifene". J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 107 (3–5): 202–10. doi:10.1016/j.jsbmb.2007.03.046. PMC 2697607. PMID 17662596.

- Pasqualini JR (17 July 2002). Breast Cancer: Prognosis, Treatment, and Prevention. CRC Press. pp. 222–. ISBN 978-0-203-90924-9.

- Yao AP (2005). Trends in Breast Cancer Research. Nova Publishers. pp. 58–. ISBN 978-1-59454-134-6.

- Berning B, Coelingh Bennink HJ, Fauser BC (2009). "Tibolone and its effects on bone: a review". Climacteric. 4 (2): 120–136. doi:10.1080/cmt.4.2.120.136. PMID 11428176.

- Goldstein I, Meston CM, Davis S, Traish A (17 November 2005). Women's Sexual Function and Dysfunction: Study, Diagnosis and Treatment. CRC Press. pp. 556–. ISBN 978-1-84214-263-9.

Further reading

- "Tibolone (Livial)--a new steroid for the menopause". Drug Ther Bull. 29 (20): 77–8. September 1991. PMID 1935591.

- Ross LA, Alder EM (February 1995). "Tibolone and climacteric symptoms". Maturitas. 21 (2): 127–36. doi:10.1016/0378-5122(94)00888-E. PMID 7752950.

- Rymer JM (June 1998). "The effects of tibolone". Gynecol. Endocrinol. 12 (3): 213–20. doi:10.3109/09513599809015548. PMID 9675570.

- Albertazzi P, Di Micco R, Zanardi E (November 1998). "Tibolone: a review". Maturitas. 30 (3): 295–305. doi:10.1016/S0378-5122(98)00059-0. PMID 9881330.

- Ginsburg J, Prelevic GM (1999). "Tibolone and the serum lipid/lipoprotein profile: does this have a role in cardiovascular protection in postmenopausal women?". Menopause. 6 (2): 87–9. doi:10.1097/00042192-199906020-00002. PMID 10374212.

- Gompel A, Jacob D, de Chambine S, Mimoun M, Decroix Y, Rostene W, Poitout P (May 1999). "[Action of SERM and SAS (tibolone) on breast tissue]". Contracept Fertil Sex (in French). 27 (5): 368–75. PMID 10401183.

- Maudelonde T, Brouillet JP, Pujol P (September 1999). "[Anti-estrogens, selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERM), tibolone: modes of action]". Contracept Fertil Sex (in French). 27 (9): 620–4. PMID 10540506.

- von Holst T (April 2000). "[Alternatives to hormone replacement therapy: raloxifene and tibolone]". Z Arztl Fortbild Qualitatssich (in German). 94 (3): 205–9. PMID 10802895.

- Schoonen WG, Deckers GH, de Gooijer ME, de Ries R, Kloosterboer HJ (2000). "Hormonal properties of norethisterone, 7α-methyl-norethisterone and their derivatives". J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 74 (4): 213–22. doi:10.1016/s0960-0760(00)00125-4. PMID 11162927.

- Palacios S (January 2001). "Tibolone: what does tissue specific activity mean?". Maturitas. 37 (3): 159–65. doi:10.1016/S0378-5122(00)00184-5. PMID 11173177.

- Kloosterboer HJ (2001). "Tibolone: a steroid with a tissue-specific mode of action". J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 76 (1–5): 231–8. doi:10.1016/S0960-0760(01)00044-9. PMID 11384882.

- Berning B, Bennink HJ, Fauser BC (June 2001). "Tibolone and its effects on bone: a review". Climacteric. 4 (2): 120–36. doi:10.1080/cmt.4.2.120.136. PMID 11428176.

- "Tibolone: new type of hormone replacement". Harv Womens Health Watch. 9 (5): 5. December 2001. PMID 11751099.

- Modelska K, Cummings S (January 2002). "Tibolone for postmenopausal women: systematic review of randomized trials". J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 87 (1): 16–23. doi:10.1210/jcem.87.1.8141. PMID 11788614.

- Davis SR (2002). "The effects of tibolone on mood and libido". Menopause. 9 (3): 162–70. doi:10.1097/00042192-200205000-00004. PMID 11973439.

- Gorai I (March 2002). "[Drugs in development for the treatment of osteoporosis: Tibolone]". Nippon Rinsho (in Japanese). 60 Suppl 3: 552–71. PMID 11979954.

- Jamin C, Poncelet C, Madelenat P (September 2002). "[Tibolone]". Presse Med (in French). 31 (28): 1314–22. PMID 12355994.

- Reginster JY (October 2002). "[Postmenopausal hormonal treatment: conventional hormone replacement therapy or tibolone? Effects on bone]". J Gynecol Obstet Biol Reprod (Paris) (in French). 31 (6): 541–9. PMID 12407324.

- Purdie DW (September 2002). "What is tibolone--and is it a SPEAR?". Climacteric. 5 (3): 236–9. doi:10.1080/cmt.5.3.236.239. PMID 12419081.

- Kloosterboer HJ, Ederveen AG (December 2002). "Pros and cons of existing treatment modalities in osteoporosis: a comparison between tibolone, SERMs and estrogen (+/-progestogen) treatments". J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 83 (1–5): 157–65. doi:10.1016/S0960-0760(03)00055-4. PMID 12650712.

- de Gooyer ME, Deckers GH, Schoonen WG, Verheul HA, Kloosterboer HJ (January 2003). "Receptor profiling and endocrine interactions of tibolone". Steroids. 68 (1): 21–30. doi:10.1016/S0039-128X(02)00112-5. PMID 12475720.

- Swegle JM, Kelly MW (May 2004). "Tibolone: a unique version of hormone replacement therapy". Ann Pharmacother. 38 (5): 874–81. doi:10.1345/aph.1D462. PMID 15026563.

- Gorai I (February 2004). "[Tibolone]". Nippon Rinsho (in Japanese). 62 Suppl 2: 555–9. PMID 15035189.

- Devogelaer JP (April 2004). "A review of the effects of tibolone on the skeleton". Expert Opin Pharmacother. 5 (4): 941–9. doi:10.1517/14656566.5.4.941. PMID 15102576.

- Reed MJ, Kloosterboer HJ (August 2004). "Tibolone: a selective tissue estrogenic activity regulator (STEAR)". Maturitas. 48 Suppl 1: S4–6. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2004.02.013. PMID 15337241.

- Kloosterboer HJ (August 2004). "Tissue-selectivity: the mechanism of action of tibolone". Maturitas. 48 Suppl 1: S30–40. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2004.02.012. PMID 15337246.

- Kloosterboer HJ (September 2004). "Tissue-selective effects of tibolone on the breast". Maturitas. 49 (1): S5–S15. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2004.06.022. PMID 15351102.

- von Schoultz B (September 2004). "The effects of tibolone and oestrogen-based HT on breast cell proliferation and mammographic density". Maturitas. 49 (1): S16–21. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2004.06.011. PMID 15351103.

- Kenemans P, Speroff L (May 2005). "Tibolone: clinical recommendations and practical guidelines. A report of the International Tibolone Consensus Group". Maturitas. 51 (1): 21–8. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2005.02.011. PMID 15883105.

- Liu JH (December 2005). "Therapeutic effects of progestins, androgens, and tibolone for menopausal symptoms". Am. J. Med. 118 Suppl 12B (12): 88–92. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.09.040. PMID 16414332.

- Erel CT, Senturk LM, Kaleli S (October 2006). "Tibolone and breast cancer". Postgrad Med J. 82 (972): 658–62. doi:10.1136/pgmj.2005.037184. PMC 2653908. PMID 17068276.

- Verheul HA, Kloosterboer HJ (December 2006). "Metabolism of exogenous sex steroids and effect on brain functions with a focus on tibolone". J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 102 (1–5): 195–204. doi:10.1016/j.jsbmb.2006.09.037. PMID 17113982.

- Ettinger B (May 2007). "Tibolone for prevention and treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis". Maturitas. 57 (1): 35–8. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2007.02.008. PMID 17350774.

- Notelovitz M (January 2007). "Postmenopausal tibolone therapy: biologic principles and applied clinical practice". MedGenMed. 9 (1): 2. PMC 1924982. PMID 17435612.

- Jacobsen DE, Samson MM, Kezic S, Verhaar HJ (September 2007). "Postmenopausal HRT and tibolone in relation to muscle strength and body composition". Maturitas. 58 (1): 7–18. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2007.04.012. PMID 17576043.

- Campisi R, Marengo FD (2007). "Cardiovascular effects of tibolone: a selective tissue estrogenic activity regulator". Cardiovasc Drug Rev. 25 (2): 132–45. doi:10.1111/j.1527-3466.2007.00007.x. PMID 17614936.

- Wang PH, Cheng MH, Chao HT, Chao KC (June 2007). "Effects of tibolone on the breast of postmenopausal women". Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 46 (2): 121–6. doi:10.1016/S1028-4559(07)60005-9. PMID 17638619.

- Lazovic G, Radivojevic U, Marinkovic J (April 2008). "Tibolone: the way to beat many a postmenopausal ailments". Expert Opin Pharmacother. 9 (6): 1039–47. doi:10.1517/14656566.9.6.1039. PMID 18377345.

- Garefalakis M, Hickey M (2008). "Role of androgens, progestins and tibolone in the treatment of menopausal symptoms: a review of the clinical evidence". Clin Interv Aging. 3 (1): 1–8. doi:10.2147/CIA.S1043. PMC 2544356. PMID 18488873.

- Carranza Lira S (October 2008). "[Relation between hormonal therapy and tibolone with SERMs in postmenopausal women's myomes growth]". Ginecol Obstet Mex (in Spanish). 76 (10): 610–4. PMID 19062511.

- Huang KE, Baber R (August 2010). "Updated clinical recommendations for the use of tibolone in Asian women". Climacteric. 13 (4): 317–27. doi:10.3109/13697131003681458. PMC 2942871. PMID 20443720.

- Biglia N, Maffei S, Lello S, Nappi RE (November 2010). "Tibolone in postmenopausal women: a review based on recent randomised controlled clinical trials". Gynecol. Endocrinol. 26 (11): 804–14. doi:10.3109/09513590.2010.495437. PMID 20586550.

- Kotani K, Sahebkar A, Serban C, Andrica F, Toth PP, Jones SR, Kostner K, Blaha MJ, Martin S, Rysz J, Glasser S, Ray KK, Watts GF, Mikhailidis DP, Banach M (September 2015). "Tibolone decreases Lipoprotein(a) levels in postmenopausal women: A systematic review and meta-analysis of 12 studies with 1009 patients" (PDF). Atherosclerosis. 242 (1): 87–96. doi:10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2015.06.056. PMID 26186655.

- Mocellin S, Pilati P, Briarava M, Nitti D (February 2016). "Breast Cancer Chemoprevention: A Network Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials". J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 108 (2). doi:10.1093/jnci/djv318. PMID 26582062.

- Formoso G, Perrone E, Maltoni S, Balduzzi S, Wilkinson J, Basevi V, Marata AM, Magrini N, D'Amico R, Bassi C, Maestri E (October 2016). "Short-term and long-term effects of tibolone in postmenopausal women". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 10: CD008536. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008536.pub3. PMC 6458045. PMID 27733017.

- Pinto-Almazán R, Segura-Uribe JJ, Farfán-García ED, Guerra-Araiza C (2017). "Effects of Tibolone on the Central Nervous System: Clinical and Experimental Approaches". Biomed Res Int. 2017: 8630764. doi:10.1155/2017/8630764. PMC 5278195. PMID 28191467.

- Anagnostis P, Galanis P, Chatzistergiou V, Stevenson JC, Godsland IF, Lambrinoudaki I, Theodorou M, Goulis DG (May 2017). "The effect of hormone replacement therapy and tibolone on lipoprotein (a) concentrations in postmenopausal women: A systematic review and meta-analysis". Maturitas. 99: 27–36. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2017.02.009. hdl:10044/1/48763. PMID 28364865.

- Løkkegaard EL, Mørch LS (January 2018). "Tibolone and risk of gynecological hormone sensitive cancer". Int. J. Cancer. 142 (12): 2435–2440. doi:10.1002/ijc.31267. PMID 29349823.