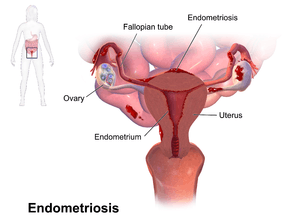

Endometriosis

Endometriosis is a condition in which cells similar to those in the endometrium, the layer of tissue that normally covers the inside of the uterus, grow outside the uterus.[6][7] Most often this is on the ovaries, fallopian tubes, and tissue around the uterus and ovaries; however, in rare cases it may also occur in other parts of the body.[2] The main symptoms are pelvic pain and infertility.[1] Nearly half of those affected have chronic pelvic pain, while in 70% pain occurs during menstruation.[1] Pain during sexual intercourse is also common.[1] Infertility occurs in up to half of women affected.[1] Less common symptoms include urinary or bowel symptoms.[1] About 25% of women have no symptoms and 85% of those seen with infertility in a tertiary center have no pain.[1][8] Endometriosis can have both social and psychological effects.[9]

| Endometriosis | |

|---|---|

| |

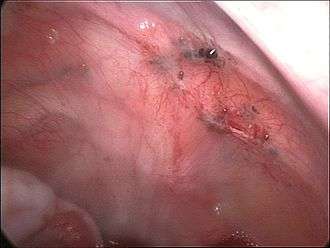

| Endometriosis as seen during laparoscopic surgery | |

| Specialty | Gynecology |

| Symptoms | Pelvic pain, infertility[1] |

| Usual onset | 30–40 years old[2][3] |

| Duration | Long term[1] |

| Causes | Unknown[1] |

| Risk factors | Family history[2] |

| Diagnostic method | Based on symptoms, medical imaging, tissue biopsy[2] |

| Differential diagnosis | Pelvic inflammatory disease, irritable bowel syndrome, interstitial cystitis, fibromyalgia[1] |

| Prevention | Combined birth control pills, exercise, avoiding alcohol and caffeine[2] |

| Treatment | NSAIDs, continuous birth control pills, intrauterine device with progestogen, surgery[2] |

| Frequency | 10.8 million (2015)[4] |

| Deaths | ~100 (2015)[5] |

The cause is not entirely clear.[10] Risk factors include having a family history of the condition.[2] The areas of endometriosis bleed each month, resulting in inflammation and scarring.[1][2] The growths due to endometriosis are not cancer.[2] Diagnosis is usually based on symptoms in combination with medical imaging;[2] however, biopsy is the surest method of diagnosis.[2] Other causes of similar symptoms include pelvic inflammatory disease, irritable bowel syndrome, interstitial cystitis, and fibromyalgia.[1] Endometriosis is commonly misdiagnosed, and women are often incorrectly told their symptoms are trivial or normal.[9]

Tentative evidence suggests that the use of combined oral contraceptives reduces the risk of endometriosis.[11][2] Exercise and avoiding large amounts of alcohol may also be preventive.[2] There is no cure for endometriosis, but a number of treatments may improve symptoms.[1] This may include pain medication, hormonal treatments or surgery.[2] The recommended pain medication is usually a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID), such as naproxen.[2] Taking the active component of the birth control pill continuously or using an intrauterine device with progestogen may also be useful.[2] Gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist (GnRH agonist) may improve the ability of those who are infertile to get pregnant.[2] Surgical removal of endometriosis may be used to treat those whose symptoms are not manageable with other treatments.[2]

One estimate is that 10.8 million people are affected globally as of 2015.[4] Other sources estimate about 6–10% of women are affected.[1] Endometriosis is most common in those in their thirties and forties; however, it can begin in girls as early as eight years old.[2][3] It results in few deaths.[12] Endometriosis was first determined to be a separate condition in the 1920s.[13] Before that time, endometriosis and adenomyosis were considered together.[13] It is unclear who first described the disease.[13]

Signs and symptoms

Pain and infertility are common symptoms, although 20-25% of women are asymptomatic. [1]

Pelvic pain

A major symptom of endometriosis is recurring pelvic pain. The pain can range from mild to severe cramping or stabbing pain that occurs on both sides of the pelvis, in the lower back and rectal area, and even down the legs. The amount of pain a woman feels correlates weakly with the extent or stage (1 through 4) of endometriosis, with some women having little or no pain despite having extensive endometriosis or endometriosis with scarring, while other women may have severe pain even though they have only a few small areas of endometriosis.[14] The most severe pain is typically associated with menstruation. Pain can also start a week before a menstrual period, during and even a week after a menstrual period, or it can be constant. The pain can be debilitating and result in emotional stress.[15] Symptoms of endometriosis-related pain may include:

- dysmenorrhea – painful, sometimes disabling cramps during the menstrual period; pain may get worse over time (progressive pain), also lower back pains linked to the pelvis

- chronic pelvic pain – typically accompanied by lower back pain or abdominal pain

- dyspareunia – painful sexual intercourse

- dysuria – urinary urgency, frequency, and sometimes painful voiding [16]

- mittelschmerz – pain associated with ovulation[17]

- bodily movement pain – present during exercise, standing, or walking[16]

Compared with women with superficial endometriosis, those with deep disease appear to be more likely to report shooting rectal pain and a sense of their insides being pulled down.[18] Individual pain areas and pain intensity appear to be unrelated to the surgical diagnosis, and the area of pain unrelated to area of endometriosis.[18]

There are multiple causes of pain. Endometriosis lesions react to hormonal stimulation and may "bleed" at the time of menstruation. The blood accumulates locally if it is not cleared shortly by the immune, circulatory, and lymphatic system. This may further lead to swelling, which triggers inflammation with the activation of cytokines, which results in pain. Another source of pain is the organ dislocation that arises from adhesion binding internal organs to each other. The ovaries, the uterus, the oviducts, the peritoneum, and the bladder can be bound together. Pain triggered in this way can last throughout the menstrual cycle, not just during menstrual periods.[19]

Also, endometriotic lesions can develop their own nerve supply, thereby creating a direct and two-way interaction between lesions and the central nervous system, potentially producing a variety of individual differences in pain that can, in some women, become independent of the disease itself.[14] Nerve fibres and blood vessels are thought to grow into endometriosis lesions by a process known as neuroangiogenesis.[20]

Infertility

About a third of women with infertility have endometriosis.[1] Among women with endometriosis about 40% are infertile.[1] The pathogenesis of infertility is dependent on the stage of disease: in early stage disease, it is hypothesised that this is secondary to an inflammatory response that impairs various aspects of conception, whereas in later stage disease distorted pelvic anatomy and adhesions contribute to impaired fertilisation.[21]

Other

Other symptoms include diarrhea or constipation, chronic fatigue, nausea and vomiting, headaches, low-grade fevers, heavy and/or irregular periods, and hypoglycemia.[22][23][16]

There is an association between endometriosis and certain types of cancers, notably some types of ovarian cancer,[24][25] non-Hodgkin's lymphoma and brain cancer.[26] Endometriosis is unrelated to endometrial cancer.[27]

Rarely, endometriosis can cause endometrial tissue to be found in other parts of the body. Thoracic endometriosis occurs when endometrial tissue implants in the lungs or pleura. Manifestations of this include coughing up blood, a collapsed lung, or bleeding into the pleural space.[28]

Stress may be a cause or a consequence of endometriosis.[29]

Risk factors

Genetics

Endometriosis is a heritable condition that is influenced by both genetic and environmental factors.[30] Daughters or sisters of women with endometriosis are at higher risk of developing endometriosis themselves; low progesterone levels may be genetic, and may contribute to a hormone imbalance.[31] There is an approximate six-fold increased incidence in women with an affected first-degree relative.[32]

It has been proposed that endometriosis results from a series of multiple hits within target genes, in a mechanism similar to the development of cancer.[30] In this case, the initial mutation may be either somatic or heritable.[30]

Individual genomic changes (found by genotyping including genome-wide association studies) that have been associated with endometriosis include:[33][34][35]

| Chromosome | Gene/Region of Mutation | Gene Product | Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | WNT4 | Wingless-type MMTV integration site family member 4 | Vital for development of the female reproductive organs |

| 2 | GREB1/FN1 | Growth regulation by estrogen in breast cancer 1/Fibronectin 1 | Early response gene in the estrogen regulation pathway/Cell adhesion and migration processes |

| 6 | ID4 | Inhibitor of DNA binding 4 | Ovarian oncogene, biological function unknown |

| 7 | 7p15.2 | Transcription factors | Influence transcriptional regulation of uterine development |

| 9 | CDKN2BAS | Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2B antisense RNA | Regulation of tumour suppressor genes |

| 10 | 10q26 | ||

| 12 | VEZT | Vezatin, an adherens junction transmembrane protein | Tumor suppressor gene |

| 19 | MUC16 (CA-125) | Mucin 16, cell surface associated | Form protective mucous barriers |

There are many findings of altered gene expression and epigenetics, but both of these can also be a secondary result of, for example, environmental factors and altered metabolism. Examples of altered gene expression include that of miRNAs.[30]

Environmental toxins

Some factors associated with endometriosis include:

- prolonged exposure to estrogen; for example, in late menopause[36] or early menarche[37][38]

- obstruction of menstrual outflow; for example, in Müllerian anomalies[36]

Several studies have investigated the potential link between exposure to dioxins and endometriosis, but the evidence is equivocal and potential mechanisms are poorly understood.[39] A 2004 review of studies of dioxin and endometriosis concluded that "the human data supporting the dioxin-endometriosis association are scanty and conflicting",[40] and a 2009 follow-up review also found that there was "insufficient evidence" in support of a link between dioxin exposure and women developing endometriosis.[41] A 2008 review concluded that more work was needed, stating that "although preliminary work suggests a potential involvement of exposure to dioxins in the pathogenesis of endometriosis, much work remains to clearly define cause and effect and to understand the potential mechanism of toxicity".[42]

Pathophysiology

While the exact cause of endometriosis remains unknown, many theories have been presented to better understand and explain its development. These concepts do not necessarily exclude each other. The pathophysiology of endometriosis is likely to be multifactorial and to involve an interplay between several factors.[30]

Formation

The main theories for the formation of the ectopic endometrium include retrograde menstruation, Müllerianosis, coelomic metaplasia, vascular dissemination of stem cells, and surgical transplantation were postulated as early as 1870. Each is further described below.[43][44]

Retrograde menstruation theory

The theory of retrograde menstruation (also called the implantation theory or transplantation theory) is the most commonly accepted theory for the dissemination and transformation of ectopic endometrium into endometriosis. It suggests that during a woman's menstrual flow, some of the endometrial debris flow backward through the Fallopian tubes and into the peritoneal cavity, attaching itself to the peritoneal surface (the lining of the abdominal cavity) where it can proceed to invade the tissue as or transform into endometriosis. It is not clear at what stage the transformation of endometrium, or any cell of origin such as stem cells or coelomic cells (see those theories below), to endometriosis begins. [30][43][45]

Retrograde menstruation alone is not able to explain all instances of endometriosis, and additional factors such as genetics, immunology, stem cell migration, and coelomic metaplasia (see "Other theories" on this page) are needed to account for disseminated disease and why many women with retrograde menstruation are not diagnosed with endometriosis. In addition, endometriosis has shown up in people who have never experienced menstruation including men,[46] fetuses,[47] and prepubescent girls.[48][49] Further theoretical additions are needed to compliment the retrograde menstruation theory to explain why cases of endometriosis show up in the brain[50] and lungs.[51] This theory has numerous other associated issues.[52]

Researchers are investigating the possibility that the immune system may not be able to cope with the cyclic onslaught of retrograde menstrual fluid. In this context there is interest in studying the relationship of endometriosis to autoimmune disease, allergic reactions, and the impact of toxic materials.[53][54] It is still unclear what, if any, causal relationship exists between toxic materials, autoimmune disease, and endometriosis. There are immune system changes in women with endometriosis, such as an increase of macrophage-derived secretion products, but it is unknown if these are contributing to the disorder or are reactions from it.[55]

In addition, at least one study found that endometriotic lesions differ in their biochemistry from artificially transplanted ectopic tissue.[56] This is likely because the cells that give rise to endometriosis are a side population of cells.[30] Similarly, there are changes in for example the mesothelium of the peritoneum in women with endometriosis, such as loss of tight junctions, but it is unknown if these are causes or effects of the disorder.[55]

In rare cases where imperforate hymen does not resolve itself prior to the first menstrual cycle and goes undetected, blood and endometrium are trapped within the uterus of the woman until such time as the problem is resolved by surgical incision. Many health care practitioners never encounter this defect, and due to the flu-like symptoms it is often misdiagnosed or overlooked until multiple menstrual cycles have passed. By the time a correct diagnosis has been made, endometrium and other fluids have filled the uterus and Fallopian tubes with results similar to retrograde menstruation resulting in endometriosis. The initial stage of endometriosis may vary based on the time elapsed between onset and surgical procedure.

The theory of retrograde menstruation as a cause of endometriosis was first proposed by John A. Sampson.[43][57]

Other theories

- Stem cells: Endometriosis may arise from stem cells from bone marrow and potentially other sources. In particular, this theory explains endometriosis found in areas remote from the pelvis such as the brain or lungs.[44] Stem cells may be from local cells such as the peritoneum (see coelomic metaplasia below) or cells disseminated in the blood stream (see vascular dissemination below) such as those from the bone marrow.[43][44][58]

- Vascular dissemination: Vascular dissemination is a 1927 theory that has been revived with new studies of bone-marrow stem cells involved in pathogenesis.[44][58]

- Environment: Environmental toxins (e.g., dioxin, nickel) may cause endometriosis.[59][60]

- Müllerianosis: A theory supported by foetal autopsy is that cells with the potential to become endometrial, which are laid down in tracts during embryonic development called the female reproductive (Müllerian) tract as it migrates downward at 8–10 weeks of embryonic life, could become dislocated from the migrating uterus and act like seeds or stem cells.[43][61]

- Coelomic metaplasia: Coelomic cells which are the common ancestor of endometrial and peritoneal cells may undergo metaplasia (transformation) from one type of cell to the other, perhaps triggered by inflammation.[43][62]

- Vasculogenesis: Up to 37% of the microvascular endothelium of ectopic endometrial tissue originates from endothelial progenitor cells, which result in de novo formation of microvessels by the process of vasculogenesis rather than the conventional process of angiogenesis.[63]

- Neural growth: An increased expression of new nerve fibres is found in endometriosis but does not fully explain the formation of ectopic endometrial tissue and is not definitely correlated with the amount of perceived pain.[64]

- Autoimmune: Graves disease is an autoimmune disease characterized by hyperthyroidism, goiter, ophthalmopathy, and dermopathy. Women with endometriosis had higher rates of Graves disease. One of these potential links between Graves disease and endometriosis is autoimmunity.[65][66]

- Oxidative stress: Influx of Iron is associated with the local destruction of the peritoneal mesothelium, leading to the adhesion of ectopic endometrial cells.[67] Peritoneal iron overload has been suggested to be caused by the destruction of erythrocytes, which contain the iron-binding protein hemoglobin, or a deficiency in the peritoneal iron metabolism system.[67] Oxidative stress activity and reactive oxygen species (such as superoxide anions and peroxide levels) are reported to be higher than normal in people with endometriosis.[67] Oxidative stress and the presence of excess ROS can damage tissue and induce rapid cellular division.[67] Mechanistically, there are several cellular pathways by which oxidative stress may lead to or may induce proliferation of endometriotic lesions, including the mitogen activated protein (MAP) kinase pathway and the extracellular signal-related kinase (ERK) pathway.[67] Activation of both of the MAP and ERK pathways lead to increased levels of c-Fos and c-Jun, which are proto-oncogenes that are associated with high-grade lesions.[67]

Localization

Most often, endometriosis is found on the:

- ovaries

- fallopian tubes

- tissues that hold the uterus in place (ligaments)

- outer surface of the uterus[2]

Less common sites are:

Rarely, endometriosis appears in other parts of the body, such as the lungs, brain, and skin.[2]

Rectovaginal or bowel endometriosis affects approximately 5-12% of women with endometriosis, and can cause severe pain with bowel movements.[68]

Endometriosis may spread to the cervix and vagina or to sites of a surgical abdominal incision, known as "scar endometriosis."[69] Risk factors for scar endometriosis include previous abdominal surgeries, such as a hysterotomy or cesarean section, or ectopic pregnancies, salpingostomy puerperal sterilization, laparoscopy, amniocentesis, appendectomy, episiotomy, vaginal hysterectomies, and hernia repair.[70][71][72]

Endometriosis may also present with skin lesions in cutaneous endometriosis.

Less commonly lesions can be found on the diaphragm. Diaphragmatic endometriosis is rare, almost always on the right hemidiaphragm, and may inflict the cyclic pain of the right shoulder just before and during a menstrual period. Rarely, endometriosis can be extraperitoneal and is found in the lungs and CNS.[73]

Diagnosis

A health history and a physical examination can lead the health care practitioner to suspect endometriosis. The potential benefits or harms related to any combination of non-invasive diagnostic tests for endometriosis are not clear (there is insufficient research) compared to the 'gold standard' of undergoing diagnostic surgery.[74]

In the UK, there is an average of 7.5 years between a woman first seeing a doctor about their symptoms and receiving a firm diagnosis.[75]

Laparoscopy

Laparoscopy, a surgical procedure where a camera is used to look inside the abdominal cavity, is the only way to officially diagnose the extent and severity of endometriosis.[76]

Reviews in 2019 and 2020 concluded that 1) with advances in imaging, endometriosis diagnosis should no longer be considered synonymous with immediate laparoscopy for diagnosis, and 2) endometriosis should be classified a syndrome that requires confirmation of visible lesions seen at laparoscopy in addition to characteristic symptoms. [77][78]

Laparoscopy permits lesion visualization unless the lesion is visible externally (e.g., an endometriotic nodule in the vagina).[76] If the growths (lesions) are not visible, a biopsy may be taken to determine the diagnosis.[79] Surgery for diagnoses also allows for surgical treatment of endometriosis at the same time.

During a laparoscopic procedure lesions can appear dark blue, powder-burn black, red, white, yellow, brown or non-pigmented. Lesions vary in size.[80] Some within the pelvis walls may not be visible, as normal-appearing peritoneum of infertile women reveals endometriosis on biopsy in 6–13% of cases.[81] Early endometriosis typically occurs on the surfaces of organs in the pelvic and intra-abdominal areas.[80] Health care providers may call areas of endometriosis by different names, such as implants, lesions, or nodules. Larger lesions may be seen within the ovaries as endometriomas or "chocolate cysts", "chocolate" because they contain a thick brownish fluid, mostly old blood.[80]

Frequently during diagnostic laparoscopy, no lesions are found in women with chronic pelvic pain, a symptom common to other disorders including adenomyosis, pelvic adhesions, pelvic inflammatory disease, congenital anomalies of the reproductive tract, and ovarian or tubal masses.[82]

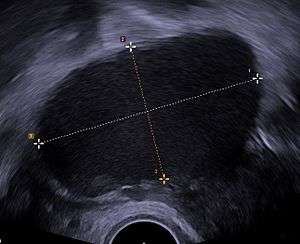

Ultrasound

Use of pelvic ultrasound may identify large endometriotic cysts (called endometriomas). However, smaller endometriosis implants cannot be visualized with ultrasound technique.[83]

Vaginal ultrasound has a clinical value in the diagnosis of endometrioma and before operating for deep endometriosis.[84] This applies to the identification of the spread of disease in women with well-established clinical suspicion of endometriosis.[84] Vaginal ultrasound is inexpensive, easily accessible, has no contraindications and requires no preparation.[84] Healthcare professionals conducting ultrasound examinations need to be experienced.[84] By extending the ultrasound assessment into the posterior and anterior pelvic compartments the sonographer is able to evaluate structural mobility and look for deep infiltrating endometriotic nodules noting the size, location and distance from the anus if applicable.[85] An improvement in sonographic detection of deep infiltrating endometriosis will not only reduce the number of diagnostic laparoscopies, it will guide management and enhance quality of life.[85]

Magnetic resonance imaging

Use of MRIs is another method to detect lesions in a non-invasive manner.[76] MRI is not widely used due to its cost and limited availability, however, it has the ability to detect deep and small endometriotic lesions.[76]

Staging

Surgically, endometriosis can be staged I–IV by the revised classification of the American Society of Reproductive Medicine from 1997.[86] The process is a complex point system that assesses lesions and adhesions in the pelvic organs, but it is important to note staging assesses physical disease only, not the level of pain or infertility. A person with Stage I endometriosis may have a little disease and severe pain, while a person with Stage IV endometriosis may have severe disease and no pain or vice versa. In principle the various stages show these findings:[87]

Stage I (Minimal)

- Findings restricted to only superficial lesions and possibly a few filmy adhesions

Stage II (Mild)

- In addition, some deep lesions are present in the cul-de-sac

Stage III (Moderate)

- As above, plus the presence of endometriomas on the ovary and more adhesions.

Stage IV (Severe)

- As above, plus large endometriomas, extensive adhesions.

Markers

An area of research is the search for endometriosis markers.[88]

In 2010, essentially all proposed biomarkers for endometriosis were of unclear medical use, although some appear to be promising.[88] The one biomarker that has been in use over the last 20 years is CA-125.[88] A 2016 review found that in those with symptoms of endometriosis; and, once ovarian cancer has been ruled out, a positive CA-125 may confirm the diagnosis.[89] Its performance in ruling out endometriosis is low.[89] CA-125 levels appear to fall during endometriosis treatment, but has not shown a correlation with disease response.[88]

Another review in 2011 identified several putative biomarkers upon biopsy, including findings of small sensory nerve fibers or defectively expressed β3 integrin subunit.[90] It has been postulated a future diagnostic tool for endometriosis will consist of a panel of several specific and sensitive biomarkers, including both substance concentrations and genetic predisposition.[88]

A 2016 review of endometrial biomarkers for diagnosing endometriosis was unable to draw conclusions due to the low quality of the evidence.[91]

MicroRNAs have the potential to be used in diagnostic and therapeutic decisions.[92]

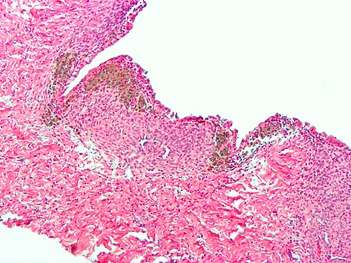

Histopathology

For a histopathological diagnosis, at least two of the following three criteria should be present:[93]

- Endometrial type stroma

- Endometrial epithelium with glands

- Evidence of chronic hemorrhage, mainly hemosiderin deposits

Immunohistochemistry has been found to be useful in diagnosing endometriosis as stromal cells have a peculiar surface antigen, CD10, thus allowing the pathologist go straight to a staining area and hence confirm the presence of stromal cells and sometimes glandular tissue is thus identified that was missed on routine H&E staining.[94]

Endometriosis, abdominal wall

Endometriosis, abdominal wall Micrograph showing endometriosis (right) and ovarian stroma (left).

Micrograph showing endometriosis (right) and ovarian stroma (left). Micrograph of the wall of an endometrioma. All features of endometriosis are present (endometrial glands, endometrial stroma and hemosiderin-laden macrophages).

Micrograph of the wall of an endometrioma. All features of endometriosis are present (endometrial glands, endometrial stroma and hemosiderin-laden macrophages).

Pain quantification

The most common pain scale for quantification of endometriosis-related pain is the visual analogue scale (VAS); VAS and numerical rating scale (NRS) were the best adapted pain scales for pain measurement in endometriosis. For research purposes, and for more detailed pain measurement in clinical practice, VAS or NRS for each type of typical pain related to endometriosis (dysmenorrhea, deep dyspareunia and non-menstrual chronic pelvic pain), combined with the clinical global impression (CGI) and a quality of life scale, are used.[95]

Prevention

Limited evidence indicates that the use of combined oral contraceptives is associated with a reduced risk of endometriosis, as is regular exercise and the avoidance of alcohol and caffeine.[2][11]

Management

While there is no cure for endometriosis, there are two types of interventions; treatment of pain and treatment of endometriosis-associated infertility.[96] In many women, menopause (natural or surgical) will abate the process.[97] In women in the reproductive years, endometriosis is merely managed: the goal is to provide pain relief, to restrict progression of the process, and to restore or preserve fertility where needed. In younger women, surgical treatment attempts to remove endometrial tissue and preserve the ovaries without damaging normal tissue.[98]

In general, the diagnosis of endometriosis is confirmed during surgery, at which time ablative steps can be taken. Further steps depend on circumstances: a woman without infertility can be managed with hormonal medication that suppresses the natural cycle and pain medication, while an infertile woman may be treated expectantly after surgery, with fertility medication, or with IVF. As to the surgical procedure, ablation (or fulguration) of endometriosis (burning and vaporizing the lesions with an electric device) has shown a high rate of short-term recurrence after the procedure. The best surgical procedure with much lower rate of short-term recurrence is to excise (cut and remove) the lesions completely.[99]

Surgery

Surgery, if done should generally be laparoscopically (through keyhole surgery) rather than open.[100] Treatment consists of the ablation or excision of the endometriosis, lysis of adhesions, resection of endometriomas, and restoration of normal pelvic anatomy as much as is possible.[100][101] Endometrioma on the ovary of any significant size (Approx. 2 cm +) —sometimes misdiagnosed as ovarian cysts— must be removed surgically because hormonal treatment alone will not remove the full endometrioma cyst, which can progress to acute pain from the rupturing of the cyst and internal bleeding. Laparoscopy, besides being used for diagnosis, can also be used to perform surgery. It's considered a "minimally invasive" surgery because the surgeon makes very small openings (incisions) at (or around) the belly button and lower portion of the belly. A thin telescope-like instrument (the laparoscope) is placed through one incision, which allows the doctor to look for endometriosis using a small camera attached to the laparoscope. Small instruments are inserted through the incisions to remove the endometriosis tissue and adhesions. Because the incisions are very small, there will only be small scars on the skin after the procedure, and all endometriosis can be removed, and women recover from surgery quicker and have a lower risk of adhesions.[102]

Endometriosis recurrence following conservative surgery is estimated as 21.5% at 2 years and 40-50% at 5 years.[103]

Historically, a hysterectomy (removal of the uterus) was thought to be a cure for endometriosis in women who do not wish to conceive. Removal of the uterus may, in some people, be beneficial as part of the treatment when the uterus itself is affected by adenomyosis. However, this should only be done when combined with removal of the endometriosis by excision, as if endometriosis is not also removed at the time of hysterectomy, pain may persist.[100]

Presacral neurectomy may be performed where the nerves to the uterus are cut. However, this technique is not usually used due to the high incidence of associated complications including presacral hematoma and irreversible problems with urination and constipation.[100]

Complications of pelvic surgery

55% to 100% of women develop adhesions following pelvic surgery,[104] which can result in infertility, chronic abdominal and pelvic pain, and difficult reoperative surgery. Trehan's temporary ovarian suspension, a technique in which the ovaries are suspended for a week after surgery may be used to reduce the incidence of adhesions after endometriosis surgery.[105][106]

Conservative treatment involves excision of endometriosis while preserving the ovaries and uterus, very important for women wishing to conceive, but may increase the risk of recurrence.[107]

Hormonal medications

- Hormonal birth control therapy: Birth control pills reduce the menstrual pain associated with endometriosis.[108] They may function by reducing or eliminating menstrual flow and providing estrogen support. Combined estrogen–progestogen birth control is the first-line treatment for most women with endometriosis due to its ability to be used over long periods of time, relative inexpensiveness and ease of use, and additional benefit of reducing ovarian/endometrial cancer risk.[109]

- Progestogens: Progesterone counteracts estrogen and inhibits the growth of the endometrium.[110] Such therapy can reduce or eliminate menstruation in a controlled and reversible fashion. Progestins are chemical variants of natural progesterone. An example of a progestin is dienogest (Visanne). Whilst progestogens are often given as part of a combined hormonal therapy with the addition of estrogen, progestogen-only therapy may be an acceptable alternative.

- Danazol (Danocrine) and gestrinone (Dimetrose, Nemestran) are suppressive steroids with some androgenic activity.[98] Both agents inhibit the growth of endometriosis but their use remains limited as they may cause masculinizing side effects such as excessive hair growth and voice changes.

- Gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) modulators: These drugs include GnRH agonists such as leuprorelin (Lupron) and GnRH antagonists such as elagolix (Orilissa) and are thought to work by decreasing estrogen levels.[111] A 2010 Cochrane review found that GnRH modulators were more effective for pain relief in endometriosis than no treatment or placebo, but were no more effective than danazol or intrauterine progestogen, and had more side effects than danazol.[111] A 2018 Swedish systematic review found that GnRH modulators had similar pain-relieving effects to gestagen, but also decreased bone density.[84]

- Aromatase inhibitors are medications that block the formation of estrogen and have become of interest for researchers who are treating endometriosis.[112] Examples of aromatase inhibitors include anastrozole and letrozole. Evidence for aromatase inhibitors is limited due to the limited number and quality of studies available, though show promising benefit in terms of pain control.[113]

Other medication

- NSAIDs: Anti-inflammatory. They are commonly used in conjunction with other therapy. For more severe cases narcotic prescription drugs may be used. NSAID injections can be helpful for severe pain or if stomach pain prevents oral NSAID use. Examples of NSAIDs include ibuprofen and naproxen.

- Opioids: Morphine sulphate tablets and other opioid painkillers work by mimicking the action of naturally occurring pain-reducing chemicals called "endorphins". There are different long acting and short acting medications that can be used alone or in combination to provide appropriate pain control.

- Following laparoscopic surgery women who were given Chinese herbs were reported to have comparable benefits to women with conventional drug treatments, though the journal article that reviewed this study also noted that "the two trials included in this review are of poor methodological quality so these findings must be interpreted cautiously. Better quality randomised controlled trials are needed to investigate a possible role for CHM [Chinese Herbal Medicine] in the treatment of endometriosis."[114]

- Pentoxifylline, an immunomodulating agent, has been theorized to improve pain as well as improve pregnancy rates in women with endometriosis. A 2012 Cochrane review found that there was not enough evidence to support the effectiveness or safety of either of these uses.[115] Current American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) guidelines do not include immune-modulators, such as pentoxifylline, in standard treatment protocols.[116]

- Angiogenesis inhibitors lack clinical evidence of efficacy in endometriosis therapy.[117] Under experimental in vitro and in vivo conditions, compounds that have been shown to exert inhibitory effects on endometriotic lesions include growth factor inhibitors, endogenous angiogenesis inhibitors, fumagillin analogues, statins, cyclo-oxygenase-2 inhibitors, phytochemical compounds, immunomodulators, dopamine agonists, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor agonists, progestins, danazol and gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists.[117] However, many of these agents are associated with undesirable side effects and more research is necessary. An ideal therapy would diminish inflammation and underlying symptoms without being contraceptive.[118][119]

The overall effectiveness of manual physical therapy to treat endometriosis has not yet been identified.[120]

Comparison of interventions

Medicinal and surgical interventions produce roughly equivalent pain-relief benefits. Recurrence of pain was found to be 44 and 53 percent with medicinal and surgical interventions, respectively.[31] Each approach has advantages and disadvantages.[62]

As of 2013 evidence on how effective medication is for relieving pain associated with endometriosis was limited .[96] A 2018 Swedish systematic review found a large number of studies but a general lack of scientific evidence for most treatments.[84] There was only one study of sufficient quality and relevance comparing the effect of surgery and non-surgery.[121] Cohort studies indicate that surgery is effective in decreasing pain.[121] Most complications occurred in cases of low intestinal anastomosis, while risk of fistula occurred in cases of combined abdominal or vaginal surgery, and urinary tract problems were common in intestinal surgery.[121] The evidence was found to be insufficient regarding surgical intervention.[121]

The advantages of surgery are demonstrated efficacy for pain control,[122] it is more effective for infertility than medicinal intervention,[98] it provides a definitive diagnosis,[98] and surgery can often be performed as a minimally invasive (laparoscopic) procedure to reduce morbidity and minimize the risk of post-operative adhesions.[123] Efforts to develop effective strategies to reduce or prevent adhesions have been undertaken, but their formation remain a frequent side effect of abdominal surgery.[104]

The advantages of physical therapy techniques are decreased cost, absence of major side-effects, it does not interfere with fertility, and near-universal increase of sexual function.[124] Disadvantages are that there are no large or long-term studies of its use for treating pain or infertility related to endometriosis.[124]

Treatment of infertility

Surgery is more effective than medicinal intervention for addressing infertility associated with endometriosis.[98] Surgery attempts to remove endometrial tissue and preserve the ovaries without damaging normal tissue.[98] In-vitro fertilization (IVF) procedures are effective in improving fertility in many women with endometriosis.[125]

During fertility treatment, the ultralong pretreatment with GnRH-agonist has a higher chance of resulting in pregnancy for women with endometriosis, compared to the short pretreatment.[84]

Outcomes

Proper counseling of women with endometriosis requires attention to several aspects of the disorder. Of primary importance is the initial operative staging of the disease to obtain adequate information on which to base future decisions about therapy. The woman's symptoms and desire for childbearing dictate appropriate therapy. Not all therapy works for all women. Some women have recurrences after surgery or pseudo-menopause. In most cases, treatment will give women significant relief from pelvic pain and assist them in achieving pregnancy.[126]

The underlying process that causes endometriosis may not cease after a surgical or medical intervention. Studies have shown that endometriosis recurs at a rate of 20 to 40 percent within five years following conservative surgery.[127] Monitoring of women consists of periodic clinical examinations and sonography.

Complications

Complications of endometriosis include internal scarring, adhesions, pelvic cysts, chocolate cysts of ovaries, ruptured cysts, and bowel and ureter obstruction resulting from pelvic adhesions.[128] Endometriosis-associated infertility can be related to scar formation and anatomical distortions due to the endometriosis.[2]

Ovarian endometriosis may complicate pregnancy by decidualization, abscess and/or rupture.[129]

Thoracic endometriosis is associated with recurrent pneumothoraces at times of a menstrual period, termed catamenial pneumothorax.[130]

A 20-year study of 12,000 women with endometriosis found that women under 40 who are diagnosed with endometriosis are 3 times more likely to have heart problems than their healthy peers.[131][132]

It results in few deaths.[12]

Epidemiology

Determining how many people have endometriosis is challenging because definitive diagnosis requires surgical visualization.[133] Criteria that are commonly used to establish a diagnosis include pelvic pain, infertility, surgical assessment, and in some cases, magnetic resonance imaging. These studies suggest that endometriosis affects approximately 11% of women in the general population.[133] It may affect more than 11% of American women between the ages of 15 and 44 years old.[2] Endometriosis is most common in those in their thirties and forties; however, it can begin in girls as early as 8 years old.[2][3]

It can affect any female, from premenarche to postmenopause, regardless of race or ethnicity or whether or not they have had children. It is primarily a disease of the reproductive years.[134] Incidences of endometriosis have occurred in postmenopausal women,[135] and in less common cases, girls may have endometriosis symptoms before they even reach menarche.[136][49]

The rate of recurrence of endometriosis is estimated to be 40-50% for adults over a 5-year period.[137] The rate of recurrence has been shown to increase with time from surgery and is not associated with the stage of the disease, initial site, surgical method used, or post-surgical treatment.[137]

History

Endometriosis was first discovered microscopically by Karl von Rokitansky in 1860,[138] although it was documented in medical texts more than 4,000 years ago.[139] The Hippocratic Corpus outlines symptoms similar to endometriosis, including uterine ulcers, adhesions, and infertility.[139] Historically, women with these symptoms were treated with leeches, straitjackets, bloodletting, chemical douches, genital mutilation, pregnancy (as a form of treatment), hanging upside down, surgical intervention, and even killing due to suspicion of demonic possession.[139] Hippocratic doctors recognized and treated chronic pelvic pain as a true organic disorder 2,500 years ago, but during the Middle Ages, there was a shift into believing that women with pelvic pain were mad, immoral, imagining the pain, or simply misbehaving.[139] The symptoms of inexplicable chronic pelvic pain were often attributed to imagined madness, female weakness, promiscuity, or hysteria.[139] The historical diagnosis of hysteria, which was thought to be a psychological disease, may have indeed been endometriosis.[139] The idea that chronic pelvic pain was related to mental illness influenced modern attitudes regarding women with endometriosis, leading to delays in correct diagnosis and indifference to the patients' true pain during the 20th century.[139]

Hippocratic doctors believed that delaying childbearing could trigger diseases of the uterus, which caused endometriosis-like symptoms. Women with dysmenorrhea were encouraged to marry and have children at a young age.[139] The fact that Hippocratics were recommending changes in marriage practices due to an endometriosis-like illness implies that this disease was likely common, with rates higher than the 5-15% prevalence that is often cited today.[139] If indeed this disorder was so common historically, this may point away from modern theories that suggest links between endometriosis and dioxins, PCBs, and chemicals.[139]

The early treatment of endometriosis was surgical and included oophorectomy (removal of the ovaries) and hysterectomy (removal of the uterus).[140] High-dose estrogen therapy for endometriosis was first reported by Karnaky in 1948 and was the only available pharmacological treatment for the condition in the early 1950s.[141][142][143] Pseudopregnancy (high-dose estrogen–progestogen therapy) for endometriosis was first described by Kistner in the late 1950s.[141][142] Pseudopregnancy as well as progestogen monotherapy dominated the treatment of endometriosis in the 1960s and 1970s.[143] Danazol was first described for endometriosis in 1971 and became the main therapy in the 1970s and 1980s.[141][142][143] In the 1980s GnRH agonists gained prominence for the treatment of endometriosis and by the 1990s had become the most widely used therapy.[142][143] Oral GnRH antagonists such as elagolix were introduced for the treatment of endometriosis in 2018.[144]

Society and culture

There are public figures who speak out about their experience with endometriosis including Whoopi Goldberg, Mel Greig, Emma Watkins, and Julianne Hough.[145][146][147][148]

The economic burden of endometriosis is widespread and multifaceted.[149] Endometriosis is a chronic disease that has direct and indirect costs which include loss of work days, direct costs of treatment, symptom management, and treatment of other associated conditions such as depression or chronic pain.[149] One factor which seems to be associated with especially high costs is the delay between onset of symptoms and diagnosis. Costs vary greatly between countries.[150]

As recently as 1995, reports found that over 50% of women with chronic pelvic pain had no organic cause, with women still often being considered mentally unstable.[151] Self-help groups say practitioners delay making the diagnosis, often because they do not consider it a possibility. In the US, as of 2007, about 27% of women with endometriosis had had the symptoms for at least six years before it is diagnosed.[152]

References

- Bulletti C, Coccia ME, Battistoni S, Borini A (August 2010). "Endometriosis and infertility". Journal of Assisted Reproduction and Genetics. 27 (8): 441–7. doi:10.1007/s10815-010-9436-1. PMC 2941592. PMID 20574791.

- "Endometriosis". womenshealth.gov. 13 February 2017. Archived from the original on 13 May 2017. Retrieved 20 May 2017.

- McGrath PJ, Stevens BJ, Walker SM, Zempsky WT (2013). Oxford Textbook of Paediatric Pain. OUP Oxford. p. 300. ISBN 9780199642656. Archived from the original on 2017-09-10.

- Vos, Theo; Allen, Christine; Arora, Megha; Barber, Ryan M.; Bhutta, Zulfiqar A.; Brown, Alexandria; Carter, Austin; Casey, Daniel C.; Charlson, Fiona J.; Chen, Alan Z.; Coggeshall, Megan; Cornaby, Leslie; Dandona, Lalit; Dicker, Daniel J.; Dilegge, Tina; Erskine, Holly E.; Ferrari, Alize J.; Fitzmaurice, Christina; Fleming, Tom; Forouzanfar, Mohammad H.; Fullman, Nancy; Gething, Peter W.; Goldberg, Ellen M.; Graetz, Nicholas; Haagsma, Juanita A.; Hay, Simon I.; Johnson, Catherine O.; Kassebaum, Nicholas J.; Kawashima, Toana; et al. (October 2016). "Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015". Lancet. 388 (10053): 1545–1602. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31678-6. PMC 5055577. PMID 27733282.

- Wang H, Naghavi M, Allen C (October 2016). "Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015". Lancet. 388 (10053): 1459–1544. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31012-1. PMC 5388903. PMID 27733281.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- "Endometriosis: Overview". nichd.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 18 May 2017. Retrieved 20 May 2017.

- "Endometriosis: Condition Information". nichd.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 30 April 2017. Retrieved 20 May 2017.

- Koninckx, Philippe R.; Meuleman, Christel; Demeyere, Stephan; Lesaffre, Emmanuel; Cornillie, Freddy J. (April 1991). "Suggestive evidence that pelvic endometriosis is a progressive disease, whereas deeply infiltrating endometriosis is associated with pelvic pain". Fertility and Sterility. 55 (4): 759–765. doi:10.1016/s0015-0282(16)54244-7. PMID 2010001.

- Culley L, Law C, Hudson N, Denny E, Mitchell H, Baumgarten M, Raine-Fenning N (1 November 2013). "The social and psychological impact of endometriosis on women's lives: a critical narrative review". Human Reproduction Update. 19 (6): 625–39. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmt027. PMID 23884896.

- Zondervan KT, Becker CM, Missmer SA (March 2020). "Endometriosis". N. Engl. J. Med. 382 (13): 1244–1256. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1810764. PMID 32212520.

- Vercellini P, Eskenazi B, Consonni D, Somigliana E, Parazzini F, Abbiati A, Fedele L (1 March 2011). "Oral contraceptives and risk of endometriosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Human Reproduction Update. 17 (2): 159–70. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmq042. PMID 20833638.

- GBD 2013 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators (January 2015). "Global, regional, and national age-sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013". Lancet. 385 (9963): 117–71. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61682-2. PMC 4340604. PMID 25530442.

- Brosens I (2012). Endometriosis: Science and Practice. John Wiley & Sons. p. 3. ISBN 9781444398496.

- Stratton P, Berkley KJ (2011). "Chronic pelvic pain and endometriosis: translational evidence of the relationship and implications". Human Reproduction Update. 17 (3): 327–46. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmq050. PMC 3072022. PMID 21106492.

- Colette S, Donnez J (July 2011). "Are aromatase inhibitors effective in endometriosis treatment?". Expert Opinion on Investigational Drugs. 20 (7): 917–31. doi:10.1517/13543784.2011.581226. PMID 21529311.

- "What are the symptoms of endometriosis?". National Institutes of Health. Retrieved 2018-10-04.

- Brown J, Farquhar C (March 2014). "Endometriosis: an overview of Cochrane Reviews". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (3): CD009590. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd009590.pub2. PMC 6984415. PMID 24610050.

- Ballard K, Lane H, Hudelist G, Banerjee S, Wright J (June 2010). "Can specific pain symptoms help in the diagnosis of endometriosis? A cohort study of women with chronic pelvic pain". Fertility and Sterility. 94 (1): 20–7. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.01.164. PMID 19342028.

- Murray MT, Pizzorno J (2012). The Encyclopedia of Natural Medicine (3rd ed.). New York, NY: Simon and Schuster.

- Asante A, Taylor RN (2011). "Endometriosis: the role of neuroangiogenesis". Annual Review of Physiology. 73: 163–82. doi:10.1146/annurev-physiol-012110-142158. PMID 21054165.

- "Treatment of infertility in women with endometriosis". uptodate.com. Retrieved 2017-12-18.

- Wolthuis AM, Meuleman C, Tomassetti C, D'Hooghe T, de Buck van Overstraeten A, D'Hoore A (November 2014). "Bowel endometriosis: colorectal surgeon's perspective in a multidisciplinary surgical team". World Journal of Gastroenterology. 20 (42): 15616–23. doi:10.3748/wjg.v20.i42.15616. PMC 4229526. PMID 25400445.

- Arbique D, Carter S, Van Sell S (September 2008). "Endometriosis can evade diagnosis". Rn. 71 (9): 28–32, quiz 33. PMID 18833741.

- Pearce CL, Templeman C, Rossing MA, Lee A, Near AM, Webb PM, Nagle CM, Doherty JA, Cushing-Haugen KL, Wicklund KG, Chang-Claude J, Hein R, Lurie G, Wilkens LR, Carney ME, Goodman MT, Moysich K, Kjaer SK, Hogdall E, Jensen A, Goode EL, Fridley BL, Larson MC, Schildkraut JM, Palmieri RT, Cramer DW, Terry KL, Vitonis AF, Titus LJ, Ziogas A, Brewster W, Anton-Culver H, Gentry-Maharaj A, Ramus SJ, Anderson AR, Brueggmann D, Fasching PA, Gayther SA, Huntsman DG, Menon U, Ness RB, Pike MC, Risch H, Wu AH, Berchuck A (April 2012). "Association between endometriosis and risk of histological subtypes of ovarian cancer: a pooled analysis of case-control studies". The Lancet. Oncology. 13 (4): 385–94. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70404-1. PMC 3664011. PMID 22361336.

- Nezhat F. Article by Prof. Farr Nezhat, MD, FACOG, FACS, University of Columbia, May 1, 2012 Archived November 2, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- Audebert A (April 2005). "[Women with endometriosis: are they different from others?]" [Women with endometriosis: are they different from others?]. Gynecologie, Obstetrique & Fertilite (in French). 33 (4): 239–46. doi:10.1016/j.gyobfe.2005.03.010. PMID 15894210.

- Rowlands IJ, Nagle CM, Spurdle AB, Webb PM (December 2011). "Gynecological conditions and the risk of endometrial cancer". Gynecologic Oncology. 123 (3): 537–41. doi:10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.08.022. PMID 21925719.

- Rousset, P.; Rousset-Jablonski, C.; Alifano, M.; Mansuet-Lupo, A.; Buy, J.-N.; Revel, M.-P. (March 2014). "Thoracic endometriosis syndrome: CT and MRI features". Clinical Radiology. 69 (3): 323–330. doi:10.1016/j.crad.2013.10.014. ISSN 1365-229X. PMID 24331768.

- Reis FM, Coutinho LM, Vannuccini S, Luisi S, Petraglia F (2020). "Is Stress a Cause or a Consequence of Endometriosis?". Reproductive Sciences. 27 (1): 39–45. doi:10.1007/s43032-019-00053-0. PMID 32046437.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Fauser BC, Diedrich K, Bouchard P, Domínguez F, Matzuk M, Franks S, Hamamah S, Simón C, Devroey P, Ezcurra D, Howles CM (2011). "Contemporary genetic technologies and female reproduction". Human Reproduction Update. 17 (6): 829–47. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmr033. PMC 3191938. PMID 21896560.

- Kapoor D, Davila W (2005). Endometriosis, Archived 2007-11-11 at the Wayback Machine eMedicine.

- Giudice LC, Kao LC (2004). "Endometriosis". Lancet. 364 (9447): 1789–99. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17403-5. PMID 15541453.

- Rahmioglu N, Nyholt DR, Morris AP, Missmer SA, Montgomery GW, Zondervan KT (September 2014). "Genetic variants underlying risk of endometriosis: insights from meta-analysis of eight genome-wide association and replication datasets". Human Reproduction Update. 20 (5): 702–16. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmu015. PMC 4132588. PMID 24676469.

- "MUC16 mucin 16, cell surface associated [Homo sapiens (human)] - Gene - NCBI". ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 2018-11-13.

- "FN1 fibronectin 1 [Homo sapiens (human)] - Gene - NCBI". ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 2018-11-13.

- Giudice LC (June 2010). "Clinical practice. Endometriosis". The New England Journal of Medicine. 362 (25): 2389–98. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp1000274. PMC 3108065. PMID 20573927.

- Treloar SA, Bell TA, Nagle CM, Purdie DM, Green AC (June 2010). "Early menstrual characteristics associated with subsequent diagnosis of endometriosis". American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 202 (6): 534.e1–6. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2009.10.857. PMID 20022587.

- Nnoaham KE, Webster P, Kumbang J, Kennedy SH, Zondervan KT (September 2012). "Is early age at menarche a risk factor for endometriosis? A systematic review and meta-analysis of case-control studies". Fertility and Sterility. 98 (3): 702–712.e6. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.05.035. PMC 3502866. PMID 22728052.

- Anger DL, Foster WG (January 2008). "The link between environmental toxicant exposure and endometriosis". Frontiers in Bioscience. 13 (13): 1578–93. doi:10.2741/2782. PMID 17981650.

- Guo SW (2004). "The link between exposure to dioxin and endometriosis: a critical reappraisal of primate data". Gynecologic and Obstetric Investigation. 57 (3): 157–73. doi:10.1159/000076374. PMID 14739528.

- Guo SW, Simsa P, Kyama CM, Mihályi A, Fülöp V, Othman EE, D'Hooghe TM (October 2009). "Reassessing the evidence for the link between dioxin and endometriosis: from molecular biology to clinical epidemiology". Molecular Human Reproduction. 15 (10): 609–24. doi:10.1093/molehr/gap075. PMID 19744969.

- Rier S, Foster WG (December 2002). "Environmental dioxins and endometriosis". Toxicological Sciences. 70 (2): 161–70. doi:10.1093/toxsci/70.2.161. PMID 12441361.

- van der Linden PJ (November 1996). "Theories on the pathogenesis of endometriosis". Human Reproduction. 11 Suppl 3: 53–65. doi:10.1093/humrep/11.suppl_3.53. PMID 9147102.

- Hufnagel D, Li F, Cosar E, Krikun G, Taylor HS (September 2015). "The Role of Stem Cells in the Etiology and Pathophysiology of Endometriosis". Seminars in Reproductive Medicine. 33 (5): 333–40. doi:10.1055/s-0035-1564609. PMC 4986990. PMID 26375413.

- Koninckx, PR (1999). "Implantation versus infiltration: the Sampson versus the endometriotic disease theory". Gynecol Obstet Invest. 47 (Supplement 1): 3–9. doi:10.1159/000052853. PMID 10087422.

- Pinkert TC, Catlow CE, Straus R (April 1979). "Endometriosis of the urinary bladder in a man with prostatic carcinoma". Cancer. 43 (4): 1562–7. doi:10.1002/1097-0142(197904)43:4<1562::aid-cncr2820430451>3.0.co;2-w. PMID 445352.

- Signorile PG, Baldi F, Bussani R, D'Armiento M, De Falco M, Baldi A (April 2009). "Ectopic endometrium in human foetuses is a common event and sustains the theory of müllerianosis in the pathogenesis of endometriosis, a disease that predisposes to cancer". Journal of Experimental & Clinical Cancer Research. 28: 49. doi:10.1186/1756-9966-28-49. PMC 2671494. PMID 19358700.

- Mok-Lin EY, Wolfberg A, Hollinquist H, Laufer MR (February 2010). "Endometriosis in a patient with Mayer-Rokitansky-Küster-Hauser syndrome and complete uterine agenesis: evidence to support the theory of coelomic metaplasia". Journal of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology. 23 (1): e35-7. doi:10.1016/j.jpag.2009.02.010. PMID 19589710.

- Marsh EE, Laufer MR (March 2005). "Endometriosis in premenarcheal girls who do not have an associated obstructive anomaly". Fertility and Sterility. 83 (3): 758–60. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2004.08.025. PMID 15749511.

- Thibodeau LL, Prioleau GR, Manuelidis EE, Merino MJ, Heafner MD (April 1987). "Cerebral endometriosis. Case report". Journal of Neurosurgery. 66 (4): 609–10. doi:10.3171/jns.1987.66.4.0609. PMID 3559727.

- Rodman MH, Jones CW (April 1962). "Catamenial hemoptysis due to bronchial endometriosis". The New England Journal of Medicine. 266 (16): 805–8. doi:10.1056/nejm196204192661604. PMID 14493132.

- "Endopædia". endopaedia.info. Retrieved 2018-07-03.

- Gleicher N, el-Roeiy A, Confino E, Friberg J (July 1987). "Is endometriosis an autoimmune disease?". Obstetrics and Gynecology. 70 (1): 115–22. PMID 3110710.

- Capellino S, Montagna P, Villaggio B, Sulli A, Soldano S, Ferrero S, Remorgida V, Cutolo M (June 2006). "Role of estrogens in inflammatory response: expression of estrogen receptors in peritoneal fluid macrophages from endometriosis". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1069: 263–7. doi:10.1196/annals.1351.024. PMID 16855153.

- Young VJ, Brown JK, Saunders PT, Horne AW (2013). "The role of the peritoneum in the pathogenesis of endometriosis". Human Reproduction Update. 19 (5): 558–69. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmt024. PMID 23720497.

- Redwine DB (October 2002). "Was Sampson wrong?". Fertility and Sterility. 78 (4): 686–93. doi:10.1016/S0015-0282(02)03329-0. PMID 12372441.

- Sampson, JA (1927). "Metastatic or embolic endometriosis, due to the menstrual dissemination of endometrial tissue into the venous circulation". Am J Pathol. 3 (2): 93–110 and 22 plates. PMC 1931779. PMID 19969738.

- Sampson, JA (1927). "Peritoneal endometriosis due to the menstrual dissemination of endometrial tissue into the peritoneal cavity". Am J Obstet Gynecol. 14 (4): 422–469. doi:10.1016/S0002-9378(15)30003-X.

- Bruner-Tran KL, Yeaman GR, Crispens MA, Igarashi TM, Osteen KG (May 2008). "Dioxin may promote inflammation-related development of endometriosis". Fertility and Sterility. 89 (5 Suppl): 1287–98. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.02.102. PMC 2430157. PMID 18394613.

- Yuk JS, Shin JS, Shin JY, Oh E, Kim H, Park WI (2015). "Nickel Allergy Is a Risk Factor for Endometriosis: An 11-Year Population-Based Nested Case-Control Study". PLOS ONE. 10 (10): e0139388. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0139388. PMC 4594920. PMID 26439741.

- Signorile PG, Baldi F, Bussani R, D'Armiento M, De Falco M, Baldi A (April 2009). "Ectopic endometrium in human foetuses is a common event and sustains the theory of müllerianosis in the pathogenesis of endometriosis, a disease that predisposes to cancer". Journal of Experimental & Clinical Cancer Research. 28: 49. doi:10.1186/1756-9966-28-49. PMC 2671494. PMID 19358700.

- Wellbery, Caroline (1999-10-15). "Diagnosis and Treatment of Endometriosis". American Family Physician. American Academy of Family Physicians. 60 (6): 1753–62, 1767–8. PMID 10537390. Archived from the original on 2011-06-06. Retrieved 2011-07-26.

- Laschke MW, Giebels C, Menger MD (2011). "Vasculogenesis: a new piece of the endometriosis puzzle". Human Reproduction Update. 17 (5): 628–36. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmr023. PMID 21586449.

- Morotti M, Vincent K, Brawn J, Zondervan KT, Becker CM (2014). "Peripheral changes in endometriosis-associated pain". Human Reproduction Update. 20 (5): 717–36. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmu021. PMC 4337970. PMID 24859987.

- Yuk JS, Park EJ, Seo YS, Kim HJ, Kwon SY, Park WI (March 2016). "Graves Disease Is Associated With Endometriosis: A 3-Year Population-Based Cross-Sectional Study". Medicine. 95 (10): e2975. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000002975. PMC 4998884. PMID 26962803.

- Giudice LC, Kao LC (2004). "Endometriosis". Lancet. 364 (9447): 1789–99. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17403-5. PMID 15541453.

- Scutiero G, Iannone P, Bernardi G, Bonaccorsi G, Spadaro S, Volta CA, Greco P, Nappi L (2017). "Oxidative Stress and Endometriosis: A Systematic Review of the Literature". Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity. 2017: 7265238. doi:10.1155/2017/7265238. PMC 5625949. PMID 29057034.

- Weed JC, Ray JE (May 1987). "Endometriosis of the bowel". Obstetrics and Gynecology. 69 (5): 727–30. PMID 3574800.

- Uzunçakmak C, Güldaş A, Ozçam H, Dinç K (2013). "Scar endometriosis: a case report of this uncommon entity and review of the literature". Case Reports in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2013: 386783. doi:10.1155/2013/386783. PMC 3665185. PMID 23762683.

- Dwivedi AJ, Agrawal SN, Silva YJ (February 2002). "Abdominal wall endometriomas". Digestive Diseases and Sciences. 47 (2): 456–61. doi:10.1023/a:1013711314870. PMID 11855568.

- Kaunitz A, Di Sant'Agnese PA (December 1979). "Needle tract endometriosis: an unusual complication of amniocentesis". Obstetrics and Gynecology. 54 (6): 753–5. PMID 160025.

- Koger KE, Shatney CH, Hodge K, McClenathan JH (September 1993). "Surgical scar endometrioma". Surgery, Gynecology & Obstetrics. 177 (3): 243–6. PMID 8356497.

- Daly S (October 18, 2004). "Endometrioma/Endometriosis". WebMD. Archived from the original on February 6, 2007. Retrieved 2006-12-19.

- Nisenblat, V; Prentice, L; Bossuyt, PM; Farquhar, C; Hull, ML; Johnson, N (13 July 2016). "Combination of the non-invasive tests for the diagnosis of endometriosis". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 7: CD012281. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012281. PMC 6458001. PMID 27405583.

- "Getting diagnosed with endometriosis | Endometriosis UK". endometriosis-uk.org. Retrieved 2018-06-13.

- Nisenblat V, Bossuyt PM, Farquhar C, Johnson N, Hull ML (February 2016). "Imaging modalities for the non-invasive diagnosis of endometriosis". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2: CD009591. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd009591.pub2. PMC 7100540. PMID 26919512.

- Chapron C, Marcellin L, Borghese B, Santulli P (November 2019). "Rethinking mechanisms, diagnosis and management of endometriosis". Nat Rev Endocrinol. 15 (11): 666–682. doi:10.1038/s41574-019-0245-z. PMID 31488888.

- "Reclassifying endometriosis as a syndrome would benefit patient care - The BMJ". Retrieved 17 August 2020.

- Office on Women’s Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (16 July 2012). Endometriosis Fact Sheet. Retrieved from Womenshealth.gov "Endometriosis". womenshealth.gov. Archived from the original on 2015-07-03. Retrieved 2015-07-11.

- Hsu AL, Khachikyan I, Stratton P (June 2010). "Invasive and noninvasive methods for the diagnosis of endometriosis". Clin Obstet Gynecol. 53 (2): 413–9. doi:10.1097/GRF.0b013e3181db7ce8. PMC 2880548. PMID 20436318.

- Nisolle M, Paindaveine B, Bourdon A, Berlière M, Casanas-Roux F, Donnez J (June 1990). "Histologic study of peritoneal endometriosis in infertile women". Fertility and Sterility. 53 (6): 984–8. doi:10.1016/s0015-0282(16)53571-7. PMID 2351237.

- Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine (April 2014). "Treatment of pelvic pain associated with endometriosis: a committee opinion". Fertility and Sterility. 101 (4): 927–35. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2014.02.012. PMID 24630080.

- "How do health care providers diagnose endometriosis?". nichd.nih.gov/. Retrieved 2019-05-06.

- "Endometriosis – Diagnosis, treatment and patient experiences". Swedish Agency for Health Technology Assessment and Assessment of Social Services (SBU). 2018-05-04. Retrieved 2018-06-13.

- Fang J, Piessens S (June 2018). "A step‐by‐step guide to sonographic evaluation of deep infiltrating endometriosis". Sonography. 5 (2): 67–75. doi:10.1002/sono.12149.

- American Society For Reproductive (May 1997). "Revised American Society for Reproductive Medicine classification of endometriosis: 1996". Fertility and Sterility. 67 (5): 817–21. doi:10.1016/S0015-0282(97)81391-X. PMID 9130884.

- Vercellini P, Fedele L, Aimi G, Pietropaolo G, Consonni D, Crosignani PG (January 2007). "Association between endometriosis stage, lesion type, patient characteristics and severity of pelvic pain symptoms: a multivariate analysis of over 1000 patients". Human Reproduction. 22 (1): 266–71. doi:10.1093/humrep/del339. PMID 16936305.

- May KE, Conduit-Hulbert SA, Villar J, Kirtley S, Kennedy SH, Becker CM (2010). "Peripheral biomarkers of endometriosis: a systematic review". Human Reproduction Update. 16 (6): 651–74. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmq009. PMC 2953938. PMID 20462942.

- Hirsch M, Duffy J, Davis CJ, Nieves Plana M, Khan KS (October 2016). "Diagnostic accuracy of cancer antigen 125 for endometriosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis". BJOG. 123 (11): 1761–8. doi:10.1111/1471-0528.14055. PMID 27173590.

- May KE, Villar J, Kirtley S, Kennedy SH, Becker CM (2011). "Endometrial alterations in endometriosis: a systematic review of putative biomarkers". Human Reproduction Update. 17 (5): 637–53. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmr013. PMID 21672902.

- Gupta, D; Hull, ML; Fraser, I; Miller, L; Bossuyt, PM; Johnson, N; Nisenblat, V (20 April 2016). "Endometrial biomarkers for the non-invasive diagnosis of endometriosis". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 4: CD012165. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012165. PMC 6953323. PMID 27094925.

- Mona Taghavipour, Fatemeh Sadoughi, Hamed Mirzaei, Bahman Yousefi, Bahram Moazzami, Shahla Chaichian, Mohammad Ali Mansournia, and Zatollah Asemi (2020). "Apoptotic functions of microRNAs in pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment of endometriosis". Cell and Bioscience. 10: 12. doi:10.1186/s13578-020-0381-0. PMC 7014775. PMID 32082539.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Aurelia Busca, Carlos Parra-Herran. "Ovary - nontumor - Nonneoplastic cysts / other - Endometriosis". Pathology Outlines. Topic Completed: 1 August 2017. Revised: 5 March 2020

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2013-05-02. Retrieved 2013-07-18.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Bourdel N, Alves J, Pickering G, Ramilo I, Roman H, Canis M (2014). "Systematic review of endometriosis pain assessment: how to choose a scale?". Human Reproduction Update. 21 (1): 136–52. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmu046. PMID 25180023.

- "What are the treatments for endometriosis". Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. Archived from the original on 3 August 2013. Retrieved 20 August 2013.

- Moen MH, Rees M, Brincat M, Erel T, Gambacciani M, Lambrinoudaki I, Schenck-Gustafsson K, Tremollieres F, Vujovic S, Rozenberg S (September 2010). "EMAS position statement: Managing the menopause in women with a past history of endometriosis". Maturitas. 67 (1): 94–7. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2010.04.018. PMID 20627430.

- Wellbery C (October 1999). "Diagnosis and treatment of endometriosis". American Family Physician. 60 (6): 1753–62, 1767–8. PMID 10537390. Archived from the original on 2013-10-29.

- "What are the treatments for endometriosis?". National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. January 31, 2017. Retrieved November 20, 2019.

- Johnson NP, Hummelshoj L (June 2013). "Consensus on current management of endometriosis". Human Reproduction. 28 (6): 1552–68. doi:10.1093/humrep/det050. PMID 23528916.

- Speroff L, Glass RH, Kase NG (1999). Clinical Gynecologic Endocrinology and Infertility (6th ed.). Lippincott Willimas Wilkins. p. 1057. ISBN 0-683-30379-1.

- "Endometriosis and Infertility: Can Surgery Help?" (PDF). American Society for Reproductive Medicine. 2008. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2010-10-11. Retrieved 31 Oct 2010.

- Guo SW (2009). "Recurrence of endometriosis and its control". Human Reproduction Update. 15 (4): 441–61. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmp007. PMID 19279046.

- Liakakos T, Thomakos N, Fine PM, Dervenis C, Young RL (2001). "Peritoneal adhesions: etiology, pathophysiology, and clinical significance. Recent advances in prevention and management". Digestive Surgery. 18 (4): 260–73. doi:10.1159/000050149. PMID 11528133.

- Trehan AK (2002). "Temporary ovarian suspension". Gynaecological Endoscopy. 11 (1): 309–314. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2508.2002.00520.x.

- Abuzeid MI, Ashraf M, Shamma FN (February 2002). "Temporary ovarian suspension at laparoscopy for prevention of adhesions". The Journal of the American Association of Gynecologic Laparoscopists. 9 (1): 98–102. doi:10.1016/S1074-3804(05)60114-4. PMID 11821616.

- Namnoum AB, Hickman TN, Goodman SB, Gehlbach DL, Rock JA (November 1995). "Incidence of symptom recurrence after hysterectomy for endometriosis". Fertility and Sterility. 64 (5): 898–902. doi:10.1016/s0015-0282(16)57899-6. PMID 7589631.

- Zorbas KA, Economopoulos KP, Vlahos NF (July 2015). "Continuous versus cyclic oral contraceptives for the treatment of endometriosis: a systematic review". Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 292 (1): 37–43. doi:10.1007/s00404-015-3641-1. PMID 25644508.

- "Endometriosis: Treatment of pelvic pain". uptodate.com. Retrieved 2017-12-18.

- Patel B, Elguero S, Thakore S, Dahoud W, Bedaiwy M, Mesiano S (2014). "Role of nuclear progesterone receptor isoforms in uterine pathophysiology". Human Reproduction Update. 21 (2): 155–73. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmu056. PMC 4366574. PMID 25406186.

- Brown J, Pan A, Hart RJ (December 2010). "Gonadotrophin-releasing hormone analogues for pain associated with endometriosis". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (12): CD008475. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008475.pub2. PMID 21154398.

- Attar E, Bulun SE (May 2006). "Aromatase inhibitors: the next generation of therapeutics for endometriosis?". Fertility and Sterility. 85 (5): 1307–18. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2005.09.064. PMID 16647373.

- Nawathe A, Patwardhan S, Yates D, Harrison GR, Khan KS (June 2008). "Systematic review of the effects of aromatase inhibitors on pain associated with endometriosis". BJOG. 115 (7): 818–22. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.2008.01740.x. PMID 18485158.

- Flower A, Liu JP, Lewith G, Little P, Li Q (May 2012). "Chinese herbal medicine for endometriosis". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (5): CD006568. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006568.pub3. PMID 22592712.

- Lu D, Song H, Li Y, Clarke J, Shi G (January 2012). "Pentoxifylline for endometriosis". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 1: CD007677. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007677.pub3. PMID 22258970.

- "Practice bulletin no. 114: management of endometriosis". Obstetrics and Gynecology. 116 (1): 223–36. July 2010. doi:10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181e8b073. PMID 20567196.

- Laschke MW, Menger MD (2012). "Anti-angiogenic treatment strategies for the therapy of endometriosis". Human Reproduction Update. 18 (6): 682–702. doi:10.1093/humupd/dms026. PMID 22718320.

- Canny GO, Lessey BA (May 2013). "The role of lipoxin A4 in endometrial biology and endometriosis". Mucosal Immunology. 6 (3): 439–50. doi:10.1038/mi.2013.9. PMC 4062302. PMID 23485944.

- Streuli I, de Ziegler D, Santulli P, Marcellin L, Borghese B, Batteux F, Chapron C (February 2013). "An update on the pharmacological management of endometriosis". Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy. 14 (3): 291–305. doi:10.1517/14656566.2013.767334. PMID 23356536.

- Valiani M, Ghasemi N, Bahadoran P, Heshmat R (2010). "The effects of massage therapy on dysmenorrhea caused by endometriosis". Iranian Journal of Nursing and Midwifery Research. 15 (4): 167–71. PMC 3093183. PMID 21589790.

- "Endometrios – diagnostik, behandling och bemötande". sbu.se (in Swedish). Statens beredning för medicinsk och social utvärdering (SBU); Swedish Agency for Health Technology Assessment and Assessment of Social Services. 2018-05-04. p. 121. Retrieved 2018-06-13.

- Kaiser A, Kopf A, Gericke C, Bartley J, Mechsner S (September 2009). "The influence of peritoneal endometriotic lesions on the generation of endometriosis-related pain and pain reduction after surgical excision". Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 280 (3): 369–73. doi:10.1007/s00404-008-0921-z. PMID 19148660.

- Radosa MP, Bernardi TS, Georgiev I, Diebolder H, Camara O, Runnebaum IB (June 2010). "Coagulation versus excision of primary superficial endometriosis: a 2-year follow-up". European Journal of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Biology. 150 (2): 195–8. doi:10.1016/j.ejogrb.2010.02.022. PMID 20303642.

- Wurn BF, Wurn LJ, Patterson K, King CR, Scharf ES (2011). "Decreasing dyspareunia and dysmenorrhea in women with endometriosis via a manual physical therapy: Results from two independent studies". Journal of Endometriosis and Pelvic Pain Disorders. 3 (4): 188–196. doi:10.5301/JE.2012.9088. PMC 6154826. Archived from the original on 2013-10-29.

- Bulletti, Carlo; Coccia, Maria; Battistoni, Sylvia; Borini, Andrea (August 2010). "Endometriosis and infertility". Journal of Assisted Reproduction and Genetics. 27 (8): 441–447. doi:10.1007/s10815-010-9436-1. PMC 2941592. PMID 20574791.

- Memarzadeh S, Muse KN, Fox, MD (September 21, 2006). "Endometriosis". Differential Diagnosis and Treatment of endometriosis. Armenian Health Network, Health.am. Archived from the original on January 31, 2007. Retrieved 2006-12-19.

- "Recurrent Endometriosis: Surgical Management". Endometriosis. The Cleveland Clinic. 7 Jan 2010. Archived from the original on 2010-05-01. Retrieved 31 Oct 2010.

- Acosta S, Leandersson U, Svensson SE, Johnsen J (May 2001). "[A case report. Endometriosis caused colonic ileus, ureteral obstruction and hypertension]" [A case report. Endometriosis caused colonic ileus, ureteral obstruction and hypertension]. Lakartidningen (in Swedish). 98 (18): 2208–12. PMID 11402601.

- Ueda Y, Enomoto T, Miyatake T, Fujita M, Yamamoto R, Kanagawa T, Shimizu H, Kimura T (June 2010). "A retrospective analysis of ovarian endometriosis during pregnancy". Fertility and Sterility. 94 (1): 78–84. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.02.092. PMID 19356751.

- Visouli AN, Zarogoulidis K, Kougioumtzi I, Huang H, Li Q, Dryllis G, Kioumis I, Pitsiou G, Machairiotis N, Katsikogiannis N, Papaiwannou A, Lampaki S, Zaric B, Branislav P, Porpodis K, Zarogoulidis P (October 2014). "Catamenial pneumothorax". Journal of Thoracic Disease. 6 (Suppl 4): S448-60. doi:10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2014.08.49. PMC 4203986. PMID 25337402.

- Wise, Jacqui (2016-04-01). "Women with endometriosis show higher risk for heart disease". BMJ. 353: i1851. doi:10.1136/bmj.i1851. ISSN 1756-1833. PMID 27036948.

- "Women with endometriosis at higher risk for heart disease | American Heart Association". newsroom.heart.org. Retrieved 2018-07-03.

- Shafrir AL, Farland LV, Shah DK, Harris HR, Kvaskoff M, Zondervan K, Missmer SA (August 2018). "Risk for and consequences of endometriosis: A critical epidemiologic review". Best Practice & Research. Clinical Obstetrics & Gynecology. 51: 1–15. doi:10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2018.06.001. PMID 30017581.

- Nothnick WB (June 2011). "The emerging use of aromatase inhibitors for endometriosis treatment". Reproductive Biology and Endocrinology. 9: 87. doi:10.1186/1477-7827-9-87. PMC 3135533. PMID 21693036.

- Bulun SE, Zeitoun K, Sasano H, Simpson ER (1999). "Aromatase in aging women". Seminars in Reproductive Endocrinology. 17 (4): 349–58. doi:10.1055/s-2007-1016244. PMID 10851574.

- Batt RE, Mitwally MF (December 2003). "Endometriosis from thelarche to midteens: pathogenesis and prognosis, prevention and pedagogy". Journal of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology. 16 (6): 337–47. doi:10.1016/j.jpag.2003.09.008. PMID 14642954.

- Guo, S.-W. (2009-03-11). "Recurrence of endometriosis and its control". Human Reproduction Update. 15 (4): 441–461. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmp007. ISSN 1355-4786. PMID 19279046.

- Batt, Ronald E. (2011). A history of endometriosis. London: Springer. pp. 13–38. doi:10.1007/978-0-85729-585-9. ISBN 978-0-85729-585-9.

- Nezhat C, Nezhat F, Nezhat C (December 2012). "Endometriosis: ancient disease, ancient treatments". Fertility and Sterility. 98 (6 Suppl): S1-62. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.08.001. PMID 23084567.

- Meigs JV (November 1941). "Endometriosis—Its Significance". Ann. Surg. 114 (5): 866–74. doi:10.1097/00000658-194111000-00007. PMC 1385984. PMID 17857917.

- J. Aiman (6 December 2012). Infertility: Diagnosis and Management. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 261–. ISBN 978-1-4613-8265-2.

- J.B. Josimovich (11 November 2013). Gynecologic Endocrinology. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 387–. ISBN 978-1-4613-2157-6.

- Robert William Kistner (1995). Kistner's Gynecology: Principles and Practice. Mosby. p. 263. ISBN 978-0-8151-7479-0.

- Barra F, Grandi G, Tantari M, Scala C, Facchinetti F, Ferrero S (April 2019). "A comprehensive review of hormonal and biological therapies for endometriosis: latest developments". Expert Opin Biol Ther. 19 (4): 343–360. doi:10.1080/14712598.2019.1581761. PMID 30763525.

- "Blossom Ball 2009 - Whoopi Goldberg". Endometriosis : Causes - Symptoms - Diagnosis - and Treatment. 2017-12-13. Retrieved 2018-11-13.

- "shocking photo shows reality of living with endometriosis". NewsComAu. Retrieved 2018-11-13.

- "When a painful period isn't normal: Julianne Hough on her surprise diagnosis". TODAY.com. Retrieved 2018-11-13.

- https://www.perthnow.com.au/entertainment/yellow-wiggle-emma-watkins-opens-up-about-the-agony-of-endometriosis-ng-b881137647z

- Gao X, Outley J, Botteman M, Spalding J, Simon JA, Pashos CL (December 2006). "Economic burden of endometriosis". Fertility and Sterility. 86 (6): 1561–72. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2006.06.015. PMID 17056043.