Datura stramonium

Datura stramonium, known by the common names thorn apple, jimsonweed (jimson weed) or devil's snare,[2] is a plant species in the nightshade family and datura genus. Its likely origin was in Central America,[2][3] and it has been introduced in many world regions.[4][5][6] It is an aggressive invasive weed in temperate climates across the world.[2]

| Jimsonweed | |

|---|---|

.jpg) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Asterids |

| Order: | Solanales |

| Family: | Solanaceae |

| Genus: | Datura |

| Species: | D. stramonium |

| Binomial name | |

| Datura stramonium | |

| Synonyms[1] | |

|

Synonymy

| |

D. stramonium has been used in various treatments of traditional medicine or drug abuse as well as a hallucinogen and deliriant that is taken entheogenically for intense visions.[2] It contains tropane alkaloids which produce the hallucinogenic properties, and may be severely toxic.[2][7]

Description

D. stramonium is a foul-smelling, erect, annual, freely branching herb that forms a bush up to 60 to 150 cm (2 to 5 ft) tall.[8][9][10]

The root is long, thick, fibrous, and white. The stem is stout, erect, leafy, smooth, and pale yellow-green to reddish purple in color. The stem forks off repeatedly into branches and each fork forms a leaf and a single, erect flower.[10]

The leaves are about 8 to 20 cm (3–8 in) long, smooth, toothed,[9] soft, and irregularly undulated.[10] The upper surface of the leaves is a darker green, and the bottom is a light green.[9] The leaves have a bitter and nauseating taste, which is imparted to extracts of the herb, and remains even after the leaves have been dried.[10]

D. stramonium generally flowers throughout the summer. The fragrant flowers are trumpet-shaped, white to creamy or violet, and 6 to 9 cm (2 1⁄2–3 1⁄2 in) long, and grow on short stems from either the axils of the leaves or the places where the branches fork. The calyx is long and tubular, swollen at the bottom, and sharply angled, surmounted by five sharp teeth. The corolla, which is folded and only partially open, is white, funnel-shaped, and has prominent ribs. The flowers open at night, emitting a pleasant fragrance, and are fed upon by nocturnal moths.[10]

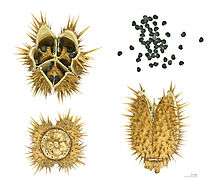

The egg-shaped seed capsule is 3 to 8 cm (1–3 in) in diameter and either covered with spines or bald. At maturity, it splits into four chambers, each with dozens of small, black seeds.[10]

Etymology and common names

The genus name is derived from the plant's Hindi name, dhatūra, ultimately from Sanskrit dhattūra 'white thorn-apple'.[11] The origin of Neo-Latin stramonium is unknown; the name Stramonia was used in the 17th century for various Datura species.[12]

In the United States, the plant is called "jimsonweed", or more rarely "Jamestown weed" deriving from the town of Jamestown, Virginia, where English soldiers consumed it while attempting to suppress Bacon's Rebellion. They spent 11 days in altered mental states:

The James-Town Weed (which resembles the Thorny Apple of Peru, and I take to be the plant so call'd) is supposed to be one of the greatest coolers in the world. This being an early plant, was gather'd very young for a boil'd salad, by some of the soldiers sent thither to quell the rebellion of Bacon (1676); and some of them ate plentifully of it, the effect of which was a very pleasant comedy, for they turned natural fools upon it for several days: one would blow up a feather in the air; another would dart straws at it with much fury; and another, stark naked, was sitting up in a corner like a monkey, grinning and making mows [grimaces] at them; a fourth would fondly kiss and paw his companions, and sneer in their faces with a countenance more antic than any in a Dutch droll.

In this frantic condition they were confined, lest they should, in their folly, destroy themselves—though it was observed that all their actions were full of innocence and good nature. Indeed, they were not very cleanly; for they would have wallowed in their own excrements if they had not been prevented. A thousand such simple tricks they played, and after eleven days returned themselves again, not remembering anything that had passed.— Robert Beverley, Jr., The History and Present State of Virginia, Book II: Of the Natural Product and Conveniencies in Its Unimprov'd State, Before the English Went Thither, 1705[13]

Common names for D. stramonium vary by region[2] and include thornapple[14], moon flower,[15] hell's bells, devil's trumpet, devil's weed, tolguacha, Jamestown weed, stinkweed, locoweed, pricklyburr, false castor oil plant,[16] and devil's cucumber.[17]

Range and habitat

D. stramonium is native to North America, but was spread widely to the Old World early.[2] It was scientifically described and named by Swedish botanist Carl Linnaeus in 1753, although it had been described a century earlier by botanists such as Nicholas Culpeper.[18] Today, it grows wild in all the world's warm and moderate regions, where it is found along roadsides and at dung-rich livestock enclosures.[19][20][21] In Europe, it is found as a weed in garbage dumps and wastelands,[19] and is toxic to animals consuming it.[22]

Through observation, the seed is thought to be carried by birds and spread in their droppings. Its seeds can lie dormant underground for years and germinate when the soil is disturbed. The Royal Horticultural Society has advised worried gardeners to dig it up or have it otherwise removed,[23] while wearing gloves to handle it.[24]

Toxicity

All parts of Datura plants contain dangerous levels of the tropane alkaloids atropine, hyoscyamine, and scopolamine, which are classified as deliriants, or anticholinergics.[2][7] The risk of fatal overdose is high among uninformed users, and many hospitalizations occur among recreational users who ingest the plant for its psychoactive effects.[7][19][25] Deliberate or inadvertent poisoning resulting from smoking jimsonweed and other related species has been reported.[26]

The amount of toxins varies widely from plant to plant. As much as a 5:1 variation can be found between plants, and a given plant's toxicity depends on its age, where it is growing, and the local weather conditions.[19] Additionally, within a given plant, toxin concentration varies by part and even from leaf to leaf. When the plant is younger, the ratio of scopolamine to atropine is about 3:1; after flowering, this ratio is reversed, with the amount of scopolamine continuing to decrease as the plant gets older.[27] In traditional cultures, a great deal of experience with and detailed knowledge of Datura was critical to minimize harm.[19] An individual seed contains about 0.1 mg of atropine, and the approximate fatal dose for adult humans is >10 mg atropine or >2–4 mg scopolamine.[28]

Datura intoxication typically produces delirium, hallucination, hyperthermia, tachycardia, bizarre behavior, urinary retention, and severe mydriasis with resultant painful photophobia that can last several days.[7] Pronounced amnesia is another commonly reported effect.[29] The onset of symptoms generally occurs around 30 to 60 minutes after ingesting the herb. These symptoms generally last from 24 to 48 hours, but have been reported in some cases to last as long as 2 weeks.[26]

As with other cases of anticholinergic poisoning, intravenous physostigmine can be administered in severe cases as an antidote.[30]

Use

Traditional medicine

The active agent in datura is atropine which has been used in traditional medicine and recreationally over centuries.[2][7] The leaves are generally smoked either in a cigarette or a pipe. During the late 18th century, James Anderson, the English Physician General of the East India Company, learned of the practice and popularized it in Europe.[31][32]

The Zuni people once used datura as an analgesic to render patients unconscious while broken bones were set.[33] The Chinese also used it as a form of anesthesia during surgery.[34]

Early European medicine

John Gerard's Herball (1597) states,[10]

"[T]he juice of Thornapple, boiled with hog's grease, cureth all inflammations whatsoever, all manner of burnings and scaldings, as well of fire, water, boiling lead, gunpowder, as that which comes by lightning and that in very short time, as myself have found in daily practice, to my great credit and profit."

William Lewis reported, in the late 18th century, that the juice could be made into "a very powerful remedy in various convulsive and spasmodic disorders, epilepsy and mania," and was also "found to give ease in external inflammations and haemorrhoids."[35]

Henry Hyde Salter discusses D. stramonium as a treatment for asthma in his 19th-century work On Asthma: its Pathology and Treatment.

Spiritualism and occult

The ancient inhabitants of what became central and southern California used to ingest the small black seeds of datura to "commune with deities through visions".[36] Across the Americas, other indigenous peoples, such as the Algonquian, Navajo, Cherokee, Luiseño and the indigenous peoples of Marie-Galante also used this plant in sacred ceremonies for its hallucinogenic properties.[37][38][39] In Ethiopia, some students and debtrawoch (lay priests), use D. stramonium to "open the mind" to be more receptive to learning, and creative and imaginative thinking.[40]

The common name "datura" has its origins in India, where the sister species Datura metel is considered particularly sacred — believed to be a favorite of Shiva in Shaivism.[41] Both Datura stramonium and D. metel have reportedly been used by some sadhus and charnel ground ascetics, such as the Aghori as both an entheogen and ordeal poison. It was sometimes mixed with cannabis as well as highly poisonous plants like Aconitum ferox to intentionally create dysphoric experiences.[42] They used unpleasant or toxic plants such as these in order to achieve spiritual liberation (moksha) in settings of extreme horror and discomfort.[43][44]

Among its sacred and visionary purposes, jimson weed has also garnered a reputation for its magical uses in various cultures throughout history. In his book, The Serpent and the Rainbow, Wade Davis identified D. stramonium, called "zombi cucumber" in Haiti, as a central ingredient of the concoction vodou priests use to create zombies.[45][46] However it has been noted that the process of zombification is not directly performed by vodou priests of the loa but rather by bokors. [47] In European witchcraft, D. stramonium was also a common ingredient used for making witches' flying ointment along with other poisonous plants of the nightshade family.[48] It was often responsible for the hallucinogenic effects of magical or lycanthropic salves and potions.[49][50]

Cultivation

Datura stramonium prefers rich, calcareous soil. Adding nitrogen fertilizer to the soil increases the concentration of alkaloids present in the plant. D. stramonium can be grown from seed, which is sown with several feet between plants. It is sensitive to frost, so should be sheltered during cold weather. The plant is harvested when the fruits are ripe, but still green. To harvest, the entire plant is cut down, the leaves are stripped from the plant, and everything is left to dry. When the fruits begin to burst open, the seeds are harvested. For intensive plantations, leaf yields of 1,100 to 1,700 kilograms per hectare (1,000 to 1,500 lb/acre) and seed yields of 780 kg/ha (700 lb/acre) are possible.[51]

In popular culture

A tea made from Jimson weed was used to kill two people in the second series of the Netflix show The Sinner.

The American artist Georgia O’Keeffe (1887–1986) painted jimson weed several times. She was fond of the flowers, which grew wild around her New Mexico house. These paintings of the exotic white pinwheel blooms, hugely magnified, are among her most familiar works.[52] In 2014 one such painting sold for $44 million, a record price for a female artist's work.[53]

References

- "Datura stramonium L. — The Plant List". www.theplantlist.org. Retrieved 20 June 2020.

- "Datura stramonium (jimsonweed)". CABI. 21 November 2018. Retrieved 6 May 2019.

- "Datura stramonium in Flora of China @ efloras.org". www.efloras.org. Retrieved 16 August 2017.

- "Datura stramonium". Germplasm Resources Information Network (GRIN). Agricultural Research Service (ARS), United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). Retrieved 5 February 2008.

- "Biota of North America Program, 2014 county distribution map". bonap.net.

- Australia, Atlas of Living. "Datura stramonium : Common thornapple | Atlas of Living Australia". bie.ala.org.au. Retrieved 16 August 2017.

- Glatstein, Miguel; Alabdulrazzaq, Fatoumah; Scolnik, Dennis (2016). "Belladonna Alkaloid Intoxication". American Journal of Therapeutics. 23 (1): e74–e77. doi:10.1097/01.mjt.0000433940.91996.16. ISSN 1075-2765. PMID 24263161. S2CID 10336715.

- Stace, Clive (1997). New Flora of the British Isles. Cambridge University Press. p. 532. ISBN 978-0-521-65315-2.

- Henkel, Alice (1911). "Jimson weed". American Medicinal Leaves and Herbs. U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 30.

- Grieve, Maud (1971). A Modern Herbal: The Medicinal, Culinary, Cosmetic and Economic Properties, Cultivation and Folk-lore of Herbs, Grasses, Fungi, Shrubs, & Trees with All Their Modern Scientific Uses, Volume 2. Dover Publications. p. 804. ISBN 978-0-486-22799-3.

- Monier-Williams, Monier (1899). A Sanskrit-English dictionary : etymologically and philologically arranged with special reference to cognate Indo-European languages. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Francis Hamilton (1823). "A Commentary on the Second Part of the Hortus Malabaricus". Transactions of the Linnean Society of London. XIV: 233.

- Beverley, Robert. "Book II: Of the Natural Product and Conveniencies in Its Unimprov'd State, Before the English Went Thither". The History and Present State of Virginia, In Four Parts. University of North Carolina. p. 24 (Book II). Retrieved 15 December 2008.

- Bunney, Sarah. Illustrated Encyclopedia of Herbs.

- "Jimsonweed". University of Texas El Paso / Austin Cooperative Pharmacy Program & Paso del Norte Health Foundation. Archived from the original on 29 July 2013. Retrieved 2013-02-13.

- Joseph Henry Maiden (1920). The Weeds of New South Wales. 1. W.A. Gullick, Government printer. p. 76.

Thorn Apple or False Castor Oil Plant)

- "Thorn-apple, Datura stramonium – Flowers – NatureGate". luontoportti.com.

- Culpeper, Nicholas (1653), Culpeper's Complete Herbal, Slough: W Foulsham & Co Ltd, pp. 368–369, ISBN 978-0-572-00203-9

- Preissel, Ulrike & Hans-Georg Preissel (2002). Brugmansia and Datura: Angel's Trumpets and Thorn Apples. Firefly Books. pp. 124–125. ISBN 978-1-55209-598-0.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Veblen, K.E. (2012). "Savanna glade hotspots: Plant community development and synergy with large herbivores". Journal of Arid Environments. 78: 119–127. Bibcode:2012JArEn..78..119V. doi:10.1016/j.jaridenv.2011.10.016.

- Oudhia P., Tripathi R.S.(1998).Allelopathic potential of Datura stramonium L.. Crop. Res. 16 (1) : 37-40.

- Cortinovis, Cristina; Caloni, Francesca (8 December 2015). "Alkaloid-containing plants poisonous to cattle and horses in Europe". Toxins. 7 (12): 5301–5307. doi:10.3390/toxins7124884. ISSN 2072-6651. PMC 4690134. PMID 26670251.

- "Deadly Harry Potter plant devil's snare turns up in Suffolk pensioner's garden". Retrieved 30 August 2017.

- "There's a devil in my garden..." Dawlish Newspapers. Retrieved 30 August 2017.

- AJ Giannini,Drugs of Abuse--Second Edition. Los Angeles, Practice Management Information Corporation, pp.48-51. ISBN 1-57066-053-0.

- Pennachio, Marcello et al. (2010). Uses and Abuses of Plant-Derived Smoke: Its Ethnobotany As Hallucinogen, Perfume, Incense, and Medicine. Oxford University Press. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-19-537001-0.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Nellis, David W. (1997). Poisonous Plants and Animals of Florida and the Caribbean. Pineapple Press. p. 237. ISBN 978-1-56164-111-6.

- Arnett AM (December 1995). "Jimson Weed (Datura stramonium) poisoning". Clinical Toxicology Review. 18 (3).

- Freye, Enno (21 September 2009). Pharmacology and Abuse of Cocaine, Amphetamines, Ecstasy and Related Designer Drugs. Springer Netherlands. pp. 217–218. doi:10.1007/978-90-481-2448-0_34. ISBN 978-90-481-2447-3.

- Goldfrank, Lewis R.; Flommenbaum, Neil (2006). Goldfrank's Toxicologic Emergencies. McGraw-Hill Professional. p. 677. ISBN 978-0-07-147914-1.

- Barceloux, Donald G. (2008). "Cáscara". Medical Toxicology of Natural Substances: Foods, Fungi, Medicinal Herbs, Plants, and Venomous Animals. John Wiley & Sons. p. 1877. ISBN 978-1-118-38276-9.

- Pennachio, Marcello et al. (2010). Uses and Abuses of Plant-Derived Smoke: Its Ethnobotany As Hallucinogen, Perfume, Incense, and Medicine. Oxford University Press. p. 6. ISBN 978-0-19-537001-0.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Turner, Matt W. (2009). Remarkable Plants of Texas: Uncommon Accounts of Our Common Natives. University of Texas Press. p. 209. ISBN 978-0-292-71851-7.

- Nellis, David W. (1997). Poisonous Plants and Animals of Florida and the Caribbean. Pineapple Press. p. 238. ISBN 978-1-56164-111-6.

- William Lewis, "An Experimental History Of The Materia Medica: Stramonium"

- Austin, Alfredo López et al. (2005). Mexico's Indigenous Past. University of Oklahoma Press. p. 22. ISBN 978-0-8061-3723-0.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Biaggioni, Italo et al. (2011). Primer on the Autonomic Nervous System. Academic Press. p. 77. ISBN 978-0-12-386525-0.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Pennachio, Marcello et al. (2010). Uses and Abuses of Plant-Derived Smoke: Its Ethnobotany As Hallucinogen, Perfume, Incense, and Medicine. Oxford University Press. pp. 82–83. ISBN 978-0-19-537001-0.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Davis, Wade (1997). The Serpent and the Rainbow: a Harvard scientist's astonishing journey into the secret societies of Haitian voodoo, zombis and magic. Simon & Schuster. p. . ISBN 978-0-684-83929-5.

- Molvaer, Reidulf Knut (1995). Socialization and Social Control in Ethiopia. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. p. 259. ISBN 978-3-447-03662-7.

- Pennachio, Marcello et al. (2010). Uses and Abuses of Plant-Derived Smoke: Its Ethnobotany As Hallucinogen, Perfume, Incense, and Medicine. Oxford University Press. p. 6. ISBN 978-0-19-537001-0.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- The Encyclopedia of Psychoactive Plants : Ethnopharmacology and its Applications, Rätsch, Christian, pub. Park Street Press U.S.A. 2005

- Indian doc. focuses on Hindu cannibal sect http://www.today.com/id/9842124#.UsLVWdIW1A0

- Svoboda, Robert (1986). Aghora: At the Left Hand of God. Brotherhood of Life. ISBN 0-914732-21-8.

- Clairvius Narcisse

- Davis, Wade (1985), The Serpent and the Rainbow, New York: Simon & Schuster

- Davis 1988.

- Rätsch, Christian, The Encyclopedia of Psychoactive Plants: Ethnopharmacology and Its Applications pub. Park Street Press 2005

- Schultes, Richard Evans; Albert Hofmann (1979). Plants of the Gods: Origins of Hallucinogenic Use New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-056089-7.

- Hansen, Harold A. The Witch's Garden pub. Unity Press 1978 ISBN 978-0913300473

- Chopra, I.C. (2006). Indigenous Drugs of India. Academic Publishers. p. 143. ISBN 9788185086804.

- "Tate Modern to show iconic flower painting by Georgia O'Keeffe". Tate. 1 March 2018. Retrieved 19 January 2019.

- Rile, Karen (1 December 2014). "Georgia O'Keeffe and the $44 Million Jimson Weed". JStor Daily. Retrieved 19 January 2019.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Datura stramonium. |

| Wikispecies has information related to Datura stramonium |

- USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service PLANTS Profile: Datura stramonium L.

- Datura stramonium at Liber Herbarum II

- Datura spp. at Erowid

- Datura stramonium Pictures and information