Luiseño

The Luiseño or Payómkawichum are an indigenous people of California who, at the time of the first contacts with the Spanish in the 16th century, inhabited the coastal area of southern California, ranging 50 miles (80 km) from the present-day southern part of Los Angeles County to the northern part of San Diego County, and inland 30 miles (48 km). In the Luiseño language, the people call themselves Payómkawichum (also spelled Payómkowishum), meaning "People of the West."[3] After the establishment of Mission San Luis Rey de Francia (The Mission of Saint Louis King of France),[4] "the Payómkawichum began to be called San Luiseños, and later, just Luiseños by Spanish missionaries due to their proximity to this San Luis Rey mission.[5]

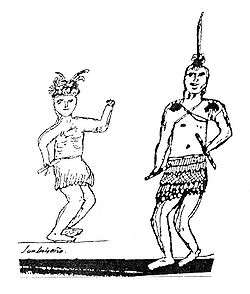

Drawing of Luiseño men in traditional dance regalia, by Pablo Tac (Luiseño, 1822–1844) | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 2,500 (including Ajachmem people)[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Languages | |

| Luiseño, English, and Spanish | |

| Religion | |

| Traditional tribal religion, Christianity | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Ajachmem (Juaneño),[2] Cupeño, Cahuilla, Serrano, Gabrielino-Tongva, Kumeyaay Kumeyaay, and Chemehuevi[3] |

Today there are six federally recognized tribes of Luiseño bands based in southern California, all with reservations. Another organized band has not received federal recognition.

History

Pre-colonization

The Payómkawichum were successful in utilizing a number of natural resources to provide food and clothing. They had a close relationship with their natural environment. They used many of the native plants, harvesting many kinds of seeds, berries, nuts, fruits, and vegetables for a varied and nutritious diet. The land also was inhabited by many different species of animals which the men hunted for game and skins. Hunters took antelopes, bobcats, deer, elk, foxes, mice, mountain lions, rabbits, wood rats, river otters, ground squirrels, and a wide variety of insects.[6] The Luiseño used toxins leached from the California buckeye to stupefy fish in order to harvest them in mountain creeks.[7]

Estimates for the pre-contact populations of most native groups in California have varied substantially. In the 1920s, A. L. Kroeber put the 1770 population of the Luiseño (including the Juaneño) at 4,000–5,000; he estimated the population in 1910 as 500.[8] The historian Raymond C. White proposed a historic population of 10,000 in his work of the 1960s.[9] Pablo Tac, born in 1820, recorded, "perhaps from oral history and official records" that approximately five thousand people were living in Payómkawichum territory prior to the arrival of the Spanish.[10]

Mission period

The first Spanish missions were established in California in 1769. For nearly 30 years, Payómkawichum "who lived in the autonomous territories on the mesas and coastal valleys" in the western region of their traditional territory, "witnessed the constant incursion of caravans that moved north and south through their land on El Camino Real."[10]

Spanish missionaries established Mission San Luis Rey de Francia entirely within the borders of Payómkawichum territory in 1798. Known as the "King of the Missions," it was founded on June 13, 1798 by Father Fermín Francisco de Lasuén, located in what is now Oceanside, California, in northern San Diego County. It was the Spanish First Military District.

Language

The Luiseño language belongs to the Cupan group of Takic languages, within the major Uto-Aztecan family of languages.[11] About 30 to 40 people speak the language. In some of the independent bands, individuals are studying the language, language preservation materials are being compiled, and singers sing traditional songs in the language.[2] Pablo Tac, born at San Luis Rey in 1820, devised the written form of Luiseño language through "his study of Latin grammar and Spanish" while working "among international scholars in Rome." Although Tac had to conform to "Latin grammatical constructions, his word choice and his narrative form, along with his continual translation between Luiseño and Spanish, establish an Indigenous framework for understanding Luiseño."[10]

Villages

- 'ahúuya, near the upper course of San Luis Rey River

- 'akíipa, near Kahpa

- 'áalapi, San Pascual south of the middle course of the San Luis Rey River

- 'áaway, on a head branch of Santa Margarita River

- Hurúmpa, west of Riverside

- Húyyulkum, on the upper course of San Luis Rey River

- 'ikáymay, near San Luis Rey Mission

- Qáxpa, on the middle course of San Luis Rey River

- Katúktu, between Santa Margarita and San Luis Rey Rivers, north of San Luis Rey

- Qée'ish, Qéch, south of San Luis Rey Mission

- Qewéw, on the upper course of San Luis Rey River

- Kóolu, near the upper course of San Luis Rey River

- Kúuki, on the upper course of San Luis Rey River

- Kwáa'alam, on the lower course of San Luis Rey River

- Maláamay, northeast of Pala

- Méexa, on Santa Margarita River northwest of Temecula

- Mixéelum pompáwvo, near Escondido

- Ngóoriva

- Pa'áa'aw, near Tái Palomar mountain

- Páayaxchi, on Elsinore Lake

- Páala, at Pala

- Páalimay, on the coast between Buena Vista and Agua Hedionda Creeks

- Panakare, north of Escondido

- Páașuku, near the headwaters of San Luis Rey River

- Páawma, east of Pala Pauma

- Pochóorivo, on the upper course of San Luis Rey River

- Sóowmay, south of the middle course of San Luis Rey River

- Șakíshmay (Luiseño or Diegueño), on the boundary line between the two peoples

- Șíikapa, Palomar

- Șuvóowu Șuvóova, east of San Jacinto Soboba

- Táaxanashpa, La Jolla

- Táa'akwi, at the head of Santa Margarita River

- Táakwish poșáppila, east of Palomar Mountain

- Tá'i, close to Palomar Mountain

- Tapá'may, north of Katúktu

- Teméeku, east of Temecula

- Tómqav, west of Pala

- 'úshmay, at Las Flores

- Waxáwmay, Guajome on San Luis Rey River above San Luis Rey

- Wiyóoya, at the mouth of San Luis Rey River

- Wi'áasamay, east of San Luis Rey

- Wáșxa,Rincon near the upper course of San Luis Rey River

- Yamí', near Húyyulkum[12]

Tribes

Today Luiseño people are enrolled in the following federally recognized tribes:

- La Jolla Band of Luiseño Indians

- Pala Band of Luiseño Indians

- Pauma Band of Luiseño Indians

- Pechanga Band of Luiseño Indians

- Rincon Band of Luiseño Indians

- Soboba Band of Luiseño Indians[13]

Additionally, the San Luis Rey Band of Luiseños is organized and active in northern San Diego County, but is not currently recognized by the United States Bureau of Indian Affairs.

Notable Luiseños

- Pete Calac (1892–1968), football player[14]

- Freddy Herrera, musician[14]

- James Luna (1950–2018), performance artist[14]

- Jamie Okuma (b. 1977), beadwork artist, fashion designer[14]

- Fritz Scholder (1937–2005), painter and sculptor[14]

- Ruth-Ann Thorn (b. 1965), art dealer, documentary film maker[14]

- Pablo Tac (1822–1841), historian, linguist[14]

See also

- Luiseño language

- Luiseño traditional narratives

- Mission Indians

- Pauma Massacre

- Temecula Massacre

- USS Luiseno (ATF-156)

- Kumeyaay people

References

- Citations

- "California Indians and Their Reservations: P. Archived January 10, 2010, at the Wayback Machine SDSU Library and Information Access. (retrieved 18 July 2010)

- Hinton 1994, pp. 28–9

- Crouthamel, S. J. "Luiseño Ethnobotany." Palomar College. 2009 (retrieved 18 July 2010)

- Pritzker 2000, p. 129

- "History". Pechanga Band of Luiseño Indians. Retrieved June 27, 2019.

- J.S. Williams, 2003

- C.M. Hogan, 2008

- Kroeber 1925, pp. 649, 883

- White 1963, pp. 117, 119

- Tac, Pablo (2011). Pablo Tac, Indigenous Scholar: Writing on Luiseño Language and Colonial History, c. 1840. University of California Press. pp. 4–5. ISBN 978-0-520-26189-1.

- Pritzker 2000, p. 130

- Swanton, John R. (1953). The Indian Tribes of North America – California. Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin. 145. Retrieved September 4, 2012.

- Pritzker 2000, p. 131

- "Famous Luiseño".

- Works cited

- Hinton, Leanne (1994). Flutes of Fire: Essays on California Indian Languages. Berkeley: Heyday Books. ISBN 0-930588-62-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hogan, C. Michael (2008). Stromberg, N. (ed.). Aesculus californica. Globaltwitcher.com.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kroeber, A. L. (1925). Handbook of the Indians of California. Washington, D.C.: Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pritzker, Barry M. (2000). A Native American Encyclopedia: History, Culture, and Peoples. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-513877-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- White, Raymond C. (1963). "Luiseño Social Organization". University of California Publications in American Archaeology and Ethnology. 48. pp. 91–194.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Bean, Lowell John and Shipek, Florence C. (1978) "Luiseño," in California, ed. Robert F. Heizer, vol. 8, Handbook of North American Indians (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution, pp. 550–563.

- Du Bois, Constance Goddard. 1904–1906. "Mythology of the Mission Indians: The Mythology of the Luiseño and Diegueño Indians of Southern California", in The Journal of the American Folk-Lore Society, Vol. XVII, No. LXVI. pp. 185–8 [1904]; Vol. XIX. No. LXXII pp. 52–60 and LXXIII. pp. 145–64. [1906].

- Sparkman, Philip Stedman (1908). The culture of the Luiseño Indians. The University Press. Retrieved August 24, 2012.

- Kroeber, Alfred Louis; Philip Stedman Sparkman; Thomas Talbot Waterman; Constance Goddard DuBois; José Francisco de Paula Señán; Vicente Francisco Sarría (1910). The religion of the Luiseño Indians of southern California. The University Press. Retrieved August 24, 2012. Volume 2

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Luiseno. |

- Soboba Band of Luiseño Indians official site

- Pechanga Band of Luiseño Indians

- Mythology of the Mission Indians, by Du Bois, 1904–1906.

- San Luis Rey Band of Luiseño Indians official site

- Agha, Marisa (March 18, 2012). "Language preservation helps American Indian students stick with college". The Sacramento Bee. Archived from the original on March 21, 2012. Retrieved August 8, 2012.