Aghori

The Aghori (Sanskrit aghora)[1] are a small group of vamacharic ascetic Shaiva sadhus. They engage in post-mortem rites. They often dwell in charnel grounds, smear cremation ashes on their bodies, and use bones from human corpses for crafting kapalas (skull cups) and jewellery. Their practices are sometimes considered contradictory to orthodox Hinduism.[2][3]

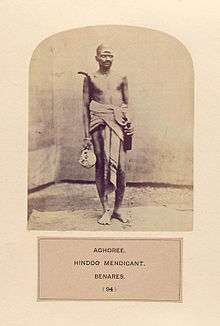

An Aghori with a human skull, c. 1875 | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| Varanasi |

Many Aghori gurus command great reverence from rural populations, as they are supposed to possess healing powers gained through their intensely eremitic rites and practices of renunciation and tápasya.

| Part of a series on |

| Shaivism |

|---|

|

|

Scriptures and texts

|

|

Philosophy

|

|

Practices |

|

Schools

Saiddhantika Non - Saiddhantika

|

|

Related

|

Beliefs and doctrines

Aghoris are devotees of Shiva manifested as Bhairava,[4] and monists who seek moksha from the cycle of reincarnation or saṃsāra. This freedom is a realization of the self's identity with the absolute. Because of this monistic doctrine, the Aghoris maintain that all opposites are ultimately illusory. The purpose of embracing pollution and degradation through various customs is the realization of non-duality (advaita) through transcending social taboos, attaining what is essentially an altered state of consciousness and perceiving the illusory nature of all conventional categories.

Aghoris are not to be confused with Shivnetras, who are also ardent devotees of Shiva but do not indulge in extreme, tamasic ritual practices. Although the Aghoris enjoy close ties with the Shivnetras, the two groups are quite distinct, Shivnetras engaging in sattvic worship.

Aghoris base their beliefs on two principles common to broader Shaiva beliefs: that Shiva is perfect (having omniscience, omnipresence and omnipotence) and that Shiva is responsible for everything that occurs: all conditions, causes and effects. Consequently, everything that exists must be perfect and to deny the perfection of anything would be to deny the sacredness of all life in its full manifestation, as well as to deny the Supreme Being.

Aghoris believe that every person's soul is Shiva but is covered by aṣṭamahāpāśa "eight great nooses or bonds", including sensual pleasure, anger, greed, obsession, fear and hatred. The practices of the Aghoris are centered around the removal of these bonds. Sādhanā in cremation grounds is used in an attempt to destroy fear; sexual practices with certain riders and controls attempt to release one from sexual desire; being naked is used in an attempt to destroy shame. On release from all the eight bonds the soul becomes sadāśiva and obtains moksha.[5]

History

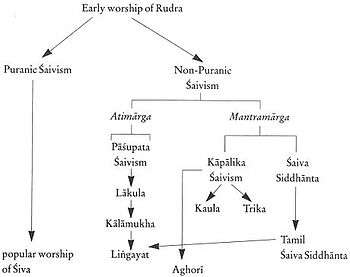

Although akin to the Kapalika ascetics of medieval Kashmir, as well as the Kalamukhas, with whom there may be a historic connection, the Aghoris trace their origin to Baba Keenaram, an ascetic who is said to have lived 150 years, dying during the second half of the 18th century.[6] Dattatreya the avadhuta, to whom has been attributed the esteemed nondual medieval song, the Avadhuta Gita, was a founding adi guru of the Aghor tradition according to Barrett (2008: p. 33):

Lord Dattatreya, an antinomian form of Shiva closely associated with the cremation ground, who appeared to Baba Keenaram atop Girnar Mountain in Gujarat. Considered to be the adi guru (ancient spiritual teacher) and founding deity of Aghor, Lord Dattatreya offered his own flesh to the young ascetic as prasād (a kind of blessing), conferring upon him the power of clairvoyance and establishing a guru-disciple relationship between them.[7]

Aghoris also hold sacred the Hindu deity Dattatreya as a predecessor to the Aghori Tantric tradition. Dattatreya was believed to be an incarnation of Brahma, Vishnu, and Shiva united in the same singular physical body. Dattatreya is revered in all schools of Tantra, which is the philosophy followed by the Aghora tradition, and he is often depicted in Hindu artwork and its holy scriptures of folk narratives, the Puranas, indulging in Aghori "left-hand" Tantric worship as his prime practice.

An aghori believes in getting into total darkness by all means, and then getting into light or self realizing. Though this is a different approach from other Hindu sects, they believe it to be effective. They are infamously known for their rites that include such as shava samskara or shava sadhana (ritual worship incorporating the use of a corpse as the altar) to invoke the mother goddess in her form as Smashan Tara (Tara of the Cremation Grounds).

In Hindu iconography, Tara, like Kali, is one of the ten Mahavidyas (wisdom goddesses) and once invoked can bless the Aghori with supernatural powers. The most popular of the ten Mahavidyas who are worshiped by Aghoris are Dhumavati, Bagalamukhi, and Bhairavi. The male Hindu deities primarily worshiped by Aghoris for supernatural powers are manifestations of Shiva, including Mahākāla, Bhairava, Virabhadra, Avadhuti, and others.

Barrett (2008: p. 161) discusses the "charnel ground sādhanā" of the Aghora in both its left and right-handed proclivities and identifies it as principally cutting through attachments and aversion and foregrounding primordiality; a view uncultured, undomesticated:

The gurus and disciples of Aghor believe their state to be primordial and universal. They believe that all human beings are natural-born Aghori. Hari Baba has said on several occasions that human babies of all societies are without discrimination, that they will play as much in their own filth as with the toys around them. Children become progressively discriminating as they grow older and learn the culturally specific attachments and aversions of their parents. Children become increasingly aware of their mortality as they bump their heads and fall to the ground. They come to fear their mortality and then palliate this fear by finding ways to deny it altogether.[8]

In this sense, the Aghora sādhanā is a process of unlearning deeply internalized cultural models. When this sādhanā takes the form of charnel ground sādhanā, the Aghori faces death as a very young child, simultaneously meditating on the totality of life at its two extremes. This ideal example serves as a prototype for other Aghor practices, both left and right, in ritual and in daily life."[9]

Adherents

Though Aghoris are prevalent in cremation grounds across India, Nepal, and even sparsely across cremation grounds in South East Asia, the secrecy of this religious sect leaves no desire for practitioners to aspire for social recognition and notoriety.[10]

Spiritual headquarters

Hinglaj Mata is the Kuladevata (patron goddess) of the Aghori. The main Aghori pilgrimage centre is Kina Ram's hermitage or ashram in Ravindrapuri, Varanasi.[11] The full name of this place is Baba Keenaram Sthal, Krim-Kund. Here, Kina Ram is buried in a tomb or samadhi which is a centre of pilgrimage for Aghoris and Aghori devotees. Present head (Abbot), since 1978, of Baba Keenaram Sthal is Baba Siddharth Gautam Ram.

According to devotees, Baba Siddharth Gautam Ram is reincarnation of Baba Keenaram himself. Apart from this, any cremation ground would be a holy place for an Aghori ascetic. The cremation grounds near the yoni pithas, 51 holy centres for worship of the Hindu Mother Goddess scattered across South Asia and the Himalayan terrain, are key locations preferred for performing sadhana by the Aghoris. They are also known to meditate and perform sadhana in haunted houses.

Medicine

Aghori practice healing through purification as a pillar of their ritual. Their patients believe the Aghoris are able to transfer health to, and pollution away from patients as a form of transformative healing, due to their superior state of body and mind of the Aghori.[12]

See also

References

- Indian doc focuses on Hindu cannibal sect (accessed: Tuesday February 9, 2010)

- "The Meanings of Death" By John Bowker, John Westerdale Bowker, p. 164, Cambridge University Press.

- "Great Sex Made Simple: Tantric Tips to Deepen Intimacy & Heighten Pleasure", by Mark A. Michaels, Patricia Johnson, Llewellyn Worldwide, p. 26, ISBN 9780738734118

- "Shiva: The Wild God of Power and Ecstasy" Page 46, by Wolf-Dieter Storl

- "Aghori". True Hindu. Retrieved 14 February 2017.

- Parry (1994).

- Barrett, Ron (2008). Aghor medicine: pollution, death, and healing in northern India. Edition: illustrated. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-25218-7, ISBN 978-0-520-25218-9. Source: (accessed: Sunday February 21, 2010), p.33.

- 'Aghora' in Monier Williams Sanskrit-English Dictionary [Online]. Source: (accessed: Tuesday February 9, 2010)

- Barrett, Ron (2008). Aghor medicine: pollution, death, and healing in northern India. Edition: illustrated. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-25218-7, ISBN 978-0-520-25218-9. p.161.

- "Indian doc focuses on Hindu cannibal sect". Today. The Associated Press. 27 October 2005. Retrieved 5 November 2019.

- Aghori, Varanasi, Retrieved 2019-11-05.

- Attewell, Guy (2008). Aghor Medicine: Pollution, Death and Healing in Northern India. 21. University of California Press. pp. 216. doi:10.1093/shm/hkn067. ISBN 978-0-520-25219-6.

Further reading

- Patel, Rajan (2016). Feast of Varanasi. Raafilms.

- Dallapiccola, Anna (2002). Dictionary of Hindu Lore and Legend. Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-500-51088-1.

- McDermott, Rachel F.; Kripal, Jeffrey J. (2003). Encountering Kālī: in the margins, at the center, in the West. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-23239-6.

- McEvilley, Thomas (2002). The Shape of Ancient Thought: comparative studies in Greek and Indian Philosophies. Allworth Communications, Inc. ISBN 978-1-58115-203-6.

- Parry, Jonathan P. (1994). Death in Banaras. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-46625-3.

- Svoboda, Robert (1986). Aghora: At the Left Hand of God. Brotherhood of Life. ISBN 0-914732-21-8.

- Svoboda, Robert (1993). Aghora II: Kundalini. Brotherhood of Life. ISBN 0-914732-31-5.

- Vishwanath Prasad Singh Ashthana, Aghor at a glance

- Vishwanath Prasad Singh Ashthana, Krim-kund Katha