Buddhism in Myanmar

Buddhism (Burmese: ထေရဝါဒဗုဒ္ဓဘာသာ) is practiced by 90% of the country's population, and is predominantly of the Theravada tradition.[2][3] It is the most religious Buddhist country in terms of the proportion of monks in the population and proportion of income spent on religion.[4] Adherents are most likely found among the dominant Bamar people, Shan, Rakhine, Mon, Karen, and Chinese who are well integrated into Burmese society. Monks, collectively known as the sangha, are venerated members of Burmese society. Among many ethnic groups in Myanmar, including the Bamar and Shan, Theravada Buddhism is practised in conjunction with nat worship, which involves the placation of spirits who can intercede in worldly affairs.

.jpg) | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| c. 48 million (88%) in 2014[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Throughout Myanmar | |

| Religions | |

| Languages | |

| Burmese and other languages |

| Part of a series on |

| Theravāda Buddhism |

|---|

|

|

|

Doctrine

|

|

Key Figures |

With regard to the daily routines of Buddhists in Myanmar, there are two most popular practices: merit-making and vipassanā. The weizza path is the least popular; it is an esoteric form somewhat linked to Buddhist aspiration that involves the occult.[5] Merit-making is the most common path undertaken by Burmese Buddhists. This path involves the observance of the Five precepts and accumulation of good merit through charity and good deeds (dana) to obtain a favourable rebirth. The vipassana path, which has gained ground since the early 1900s, is a form of insight meditation believed to lead to enlightenment. The weizza path is an esoteric system of occult practices (such as recitation of spells, samatha and alchemy) believed to lead to life as a weizza (also spelt weikza), a semi-immortal and supernatural being who awaits the appearance of the future Buddha, Maitreya (Arimeitaya).[6]

Demography

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1891 | 6,888,075 | — |

| 1901 | 9,184,121 | +33.3% |

| 1911 | 10,384,379 | +13.1% |

| 1921 | 11,201,943 | +7.9% |

| 1931 | 12,348,037 | +10.2% |

| 1973 | 17,764,008 | +43.9% |

| 1983 | 30,520,175 | +71.8% |

| 2014 | 45,185,449 | +48.1% |

| Source: 2014 Myanmar Census Report: Religion (Vol. 2-C) | ||

Buddhism is practiced by approximately 90% of the country. According to Burmese census data dating back to 1891, between 84% to 90% of the population have practiced Buddhism.

History

.jpg)

The history of Buddhism in Myanmar probably extends more than two thousand years. The Sāsana Vaṃsa (Burmese Thathana Win), written by Pinyasami in 1834, summarises much of the history of Buddhism in Myanmar. According to the Mahavamsa, a Pali chronicle of fifth century Sri Lanka, Ashoka sent two bhikkhus, Sona and Uttara, to Suvarnabhumi around 228 BC with other monks and sacred texts, including books.

An Andhra Ikshvaku inscription from about the 3rd century refers to the conversion of the Kiratas to Buddhism, who are thought to have been Tibeto-Burman-speaking peoples of Myanmar.[7] Early Chinese texts of about the same date speak of a "Kingdom of Liu-Yang," where all people worshiped the Buddha and there were several thousand samaṇas. This kingdom has been identified with a region somewhere in central Burma. A series of epigraphic records in Pali, Sanskrit, Pyu and Mon datable to the 6th and 7th centuries, has been recovered from Central and Lower Burma (Pyay and Yangon). From the 11th to 13th centuries, the Bamar kings and queens of the Pagan Kingdom built countless stupas and temples.

The Ari Buddhism era included the worship of bodhisattvas and nāgas.

Theravada Buddhism was implanted at Bagan for the first time as early as the 11th century by the Bamar king Anawrahta (1044-1077).[8] In year 1057, Anawrahta sent an army to conquer the Mon city of Thaton to obtain theTipiṭāka of the Pāli Canon. He was converted by a Mon bhikkhu, Shin Arahan, to Theravada Buddhism. Shin Arahan's advice led to acquiring thirty sets of Pali scriptures from the Mon king Manuha by force. Mon culture, from that point, came to be largely assimilated into the Bamar culture based in Bagan.

Despite attempts at reform, certain features of Ari Buddhism and traditional nat worship continued, such as reverence for the bodhisattva Avalokiteśvara (Lawka nat).

Successive kings of Bagan continued to build large numbers of monuments, temples, and pagodas in honour of Buddhism, and there is inscriptional evidence of a Theravadin vihara for bhikkhunis from 1279.

Burmese rule at Bagan continued until the first Mongol invasion of Burma in 1287. Towards the end of the 13th century, Buddhism declined due to the invading Tatars. In the 14th century, another forest lineage was imported from Sri Lanka to Ayutthaya, the capital of the Thai Ayutthaya Kingdom. A new ordination line was also imported into Burma.

The Shan, meanwhile, established themselves as rulers throughout the region now known as Myanmar. Thihathu, a Shan king, established rule in Bagan by patronising and building many monasteries and pagodas.

The Mon kingdoms, often ruled by Shan chieftains, fostered Theravada Buddhism in the 14th century. Wareru, who became king of Mottama, patronised Buddhism, and established a code of law, the Dhammasattha, compiled by Buddhist monastics. King Dhammazedi, formerly a Mon bhikkhu, established rule in the late 15th century at Inwa and unified the sangha in Mon territories. He also standardised ordination of monks set out in the Kalyani Inscriptions. Dhammazedi moved the capital back to Hanthawaddy (Bago). His mother-in-law, Queen Shin Sawbu, was also a great patron of Buddhism. She is credited for expanding and gilding the Shwedagon Pagoda, giving her own weight in gold.

The Bamars, who had fled to Taungoo before the invading Shan, established a kingdom there under the reigns of Tabinshwehti and Bayinnaung, who conquered and unified most of modern Myanmar. These monarchs also embraced Mon culture and patronised Theravada Buddhism.

In the reigns of succeeding kings, the Taungoo Dynasty became increasingly volatile and was overthrown by the Mon. In the mid-18th century, King Alaungpaya defeated the Mon, expanded the Bamar kingdoms, and established the Konbaung Dynasty. Under the rule of Bodawpaya, a son of Alaungpaya, a unified sect of monks ("Thudhamma") was created within the kingdom. Bodawpaya restored ties with Sri Lanka, allowing for mutual influence in religious affairs. During the reigns of the Konbaung kings that followed, both secular and religious literary works were created.[9] King Mindon Min moved his capital to Mandalay.

After Lower Burma had been conquered by the British, Christianity began to gain acceptance. Many monks from Lower Burma had resettled in Mandalay, but by decree of Mindon Min, they returned to serve the Buddhist laypeople. Schisms arose in the sangha; they were resolved during the Fifth Buddhist Synod, held in Mandalay in 1871.

The Fifth Council was convened at Mandalay in Myanmar on the first waning day of Tazaungmone, 1232 Myanmar Era, 2415 B.E (November 1871). The scriptures inscribed on palm-leaves could not last for a long time. Besides there might be many variations in rewriting the scriptures from copy to copy. Therefore, the scriptures were inscribed on marble slabs to dispel these disadvantages.

Two thousand and four hundred bhikkhus led by Venerable Jagarabhivamsa Thera (Tipitakadhara Mahadhammarajadhirajaguru) of Dakkhinarama Monastery, Mandalay, convened, to recite and approve the scriptures. King Mindon initiated and supported the Fifth Great Council to the end. The scriptures were first inscribed on seven hundred and twenty-nine marble slabs ) in the precinct of Lokamarajina Pagoda at the foot of Mandalay Hill. From 1860 to 1868, the Tipitaka was engraved on 729 marble slabs and assembled in the Kuthodaw Pagoda. It took seven years, six months and fourteen days to finish this work. Then the bhikkhus recited to approve the inscriptions for five months and three days. In 1871, a new hti (the gold umbrella that crowns a stupa) encrusted with jewels from the crown was also donated by Mindon Min for the Shwedagon now in British Burma. After the Fifth Great Council. the Pali Texts were translated into Myanmar language, and the Doctrinal Order was promulgated to the whole country for purpose of purification and propagation of the Buddha's Teachings.

During the British administration of Lower and Upper Burma, also known as Burma Proper, government policies were secular which meant monks were not protected by law. Nor was Buddhism patronised by the colonial government. This resulted in tensions between the colonised Buddhists and their European rulers. There was much opposition (including by the Irish monk U Dhammaloka) to the efforts by Christian missionaries to convert the Burmese people, Bamar, Shan, Mon, Rakhine and plains Karen, with one exception - the hill tribes. Today, Christianity is most commonly practised by the Chin, Kachin, and the Kayin. Notwithstanding traditional avoidance of political activity, monks often participated in politics and in the struggle for independence.

Since 1948 when the country gained its independence from Great Britain, both civil and military governments have supported Theravada Buddhism. The 1947 Constitution states, "The State recognizes the special position of Buddhism as the faith professed by the great majority of the citizens of the Union." The Ministry of Religious Affairs, created in 1948, was responsible for administering Buddhist affairs in Myanmar. In 1954, the prime minister, U Nu, convened the Sixth Buddhist Synod at Kaba Aye Pagoda in Rangoon (Yangon), which was attended by 2,500 monks, and established the World Buddhist University.

During the military rule of Ne Win (1962–1988), he attempted to reform Myanmar under the Burmese Way to Socialism which contained elements of Buddhism. In the 8888 Uprising, many monks participated and were killed by Tatmadaw soldiers. The succeeding military regime, the State Peace and Development Council (SPDC) patronised Buddhism, although persecution of Buddhists contrary to the regime, as well as persons of other religions, namely Islam and Christianity, continues.

Traditions

The culture of Myanmar is deemed synonymous with its Buddhism. There are many Burmese festivals all through the year, most of them related to Buddhism.[10] The Burmese New Year, Thingyan, also known as the Water Festival, has its origins in Hinduism but it is also a time when many Burmese boys celebrate shinbyu, a special rite of passage by which a boy enters the kyaung for a short time as a sāmaṇera.

Veneration

A Burmese Buddhist household contains an altar or shrine to the Buddha, with at least one dedicated image of the Gautama Buddha. The Buddha image is commonly placed on a "throne" called a gaw pallin (ဂေါ့ပလ္လင်, from Pali pallanka).

Before a Buddha statue is used for veneration at home, it must be formally consecrated, in a ritual called buddhābhiseka or anay gaza tin (အနေကဇာတင်ခြင်း).[11] This consecration, led by a Buddhist monk, who recites aneka jāti saṃsāraṃ (translated as 'through the round of many births I roamed'), the 153rd verse of the Dhammapada (found in the 11th chapter).[12][13]

The consecration rite, which can last a few hours, is held in the morning and consists of four primary parts:[14]

- Offerings (candles, flowers, incense, flags) made to the Buddha

- Chanting of paritta (typically Mangala Sutta, Metta Sutta, Ratana Sutta, Pubbhana Sutta)

- Recitation of aneka jāti saṃsāraṃ

- Recitation of the Twelve Nidānas

The consecration rituals are believed to imbue the Buddha image with a sacred quality that can protect the home and surroundings from misfortune and symbolically embody the powers of the Buddha.[15]

Shinbyu

It is the most important duty of all Burmese parents to make sure their sons are admitted to the Buddhist Sangha by performing a shinbyu ceremony once they have reached the age of seven or older. A symbolic procession and ceremony of exchanging princely attire with that of an ascetic follows the example of Gautama Buddha. He was born a royal prince named Siddartha Gautama, but left his palace on horseback followed by his loyal attendant Chanda (မောင်ဆန်း) after he found out that life is made up of suffering (dukkha) and the notion of self is merely an illusion (anatta) when one day he saw the "Four Great Signs" (နမိတ်ကြီးလေးပါး) - the old, the sick, the dead, and the ascetic - in the royal gardens.

All Buddhists are required to keep the basic Five Precepts (ငါးပါးသီလ), and novices are expected to keep the Ten Precepts (ဆယ်ပါးသီလ). Parents expect them to stay at the kyaung immersed in the teachings of the Buddha as members of the Sangha for three months or longer. They will have another opportunity to join the Sangha at the age of 20, taking the upasampada ordination, to become a fully ordained bhikkhu, keeping the 227 precepts of the full monastic rules or Pātimokkha and perhaps remain a monk for life.

Buddhist holidays

Thingyan usually falls in mid-April and tops the list of Public holidays in Myanmar. Vesak, the full moon in May, is the most sacred of all as the Buddha was born, became enlightened, and entered parinibbana (died) on the same day. It is celebrated by watering the Bodhi Tree.[10]

Pagoda festivals (ဘုရားပွဲ Paya pwè) held throughout the country also usually fall on full moon days and most of them will be on the full moon of Tabaung (February/March) including the Shwedagon Pagoda.[10] They attract not only crowds of pilgrims from near and far, often in caravans of bullock carts, but they also double as great market fairs where both local and itinerant traders set up their stalls and shops among food stalls, restaurants, and free open-air stage performances as well as theatre halls.

Vassa

The three monsoon months from mid-July to mid-October is Vassa (ဝါတွင်း, Burmese pronunciation: [wàdwɪ́ɰ̃]), a time when people are busy tilling their land and planting the rice paddies and bhikkhus remain in kyaungs. New robes are offered to bhikkhus at the beginning of Vassa, the end of which is marked by the Thadingyut Festival.

After the harvest, robes are again offered at Kathina (Burmese pronunciation: [kətʰèɪɰ̃]), usually held during October or November.[10] Uposatha days are observed by keeping the Eight Precepts by laypersons during Thingyan and Vassa and by devout Buddhists all the year round.

Parents and elders also receive obeisance from younger members of the family at the beginning as well as the end of lent, after the tradition established by the Buddha himself. It was during Vassa that he ascended to the Tāvatiṃsa Heaven to preach a sermon, as an act of gratitude, to his mother, who had become a deva, and he was welcomed back to earth with a great festival of lights.[10] Teachers receive the same obeisance, a tradition started by National Schools founded in defiance of the colonial administration and continued after independence by state schools.

Wedding ceremonies - nothing to do with religion and not conducted by the Sangha - are not held during the three months of Vassa, a custom which has resulted in a spate of weddings after Thadingyut or Wa-kyut, awaited impatiently by couples wanting to tie the knot.

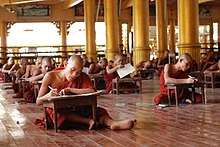

Buddhist education

Theravadins send their children to kyaungs to receive a Buddhist education, learning the Pāli Canon, the life story of Gautama Buddha, the 550 Jataka tales - most importantly the 38 Buddhist Beatitudes - as soon as they have a good grounding of the three Rs. Monks were the traditional teachers of the young and old alike until secular and missionary schools came into being during the British colonial administration.

There has been a revival of monastic schools since the 1990s with the deepening economic crisis. Children from poor families that can ill afford fees, uniforms and books have renewed the demand for a free monastic education, and minority groups such as the Shan, Pa'O, Palaung, Lahu and Wa are benefitting from this revival.[16]

Monasticism

Ordained Buddhist monks by monastic order in Myanmar (2016).[17]

Buddhist monks are venerated throughout Burmese society.[18] According to 2016 statistics published by the State Sangha Maha Nayaka Committee, the Sangha included 535,327 members, evenly split between 282,347 fully-ordained Buddhist monks (bhikku) and 252,962 novice monks (samanera).[19] There were also 60,390 thilashin (female renunciants).[19]

The majority of Buddhist monks belong to one of two primary monastic orders (ဂိုဏ်း gaing): Thudhamma Nikaya (87.24% of Buddhist monks) and the more orthodox Shwegyin Nikaya (9.47% of Buddhist monks).[17][20][17] Other minor monastic orders include the Dwara Nikaya in Lower Burma, and Hngettwin Nikaya in Mandalay, both of which have a few thousand member monks.[21][22] There are nine legally recognised monastic orders in Burma today, under the 1990 Law Concerning Sangha Organizations.[23] Burmese monastic orders do not differ in doctrine but in monastic practice, lineage and organisational structure.[24]

There are also esoteric Buddhist sects or weizza not recognised by any authority that incorporate non-Buddhist elements like alchemy, magic and occultism.[25]

The overwhelming majority of Burmese monks wear maroon robes, while others wear ochre, unlike in neighbouring Theravada countries like Thailand, Laos and Sri Lanka, where monks commonly wear saffron robes.

Women

The full bhikkhuni (nuns) lineage of Theravada Buddhism died out, and for various technical and social reasons was therefore permanently absent. The governing council of Buddhism in Myanmar has ruled that there can be no valid ordination of women in modern times, though some Burmese monks disagree. However, as in many other Theravadin countries, women have created a niche for themselves as renunciants not recognised by the state-empowered Sangharaja or even the Sangha in general. In Myanmar, these women are called thilashin.[26] A thilashin (Burmese: သီလရှင်, pronounced [θìla̰ʃɪ̀ɰ̃], "possessor of morality", from Pali sīla) is a female lay renunciant whose vows are the same as those of sāmaṇerīs "novitiate nuns". Like the maechi of neighbouring Thailand and the dasa sil mata of Sri Lanka, thilashin occupy a position somewhere between that of an ordinary lay follower and an ordained monastic. However, they are treated more favourably than most maechi, being able to receive training, practice meditation and sit for the same qualification examinations as the monks.

Thilashins observe the ten precepts and can be recognised by their pink robes, shaven head, orange or brown shawl and metal alms bowl. Thilashins go out on alms rounds on uposatha and receive uncooked rice or money.

Thilashins are addressed with the honorifics sayale (Burmese: ဆရာလေး, [sʰəjàlé] "little teacher") and daw (ဒေါ်, [dɔ̀]). These are used as honorifics to the Buddhist name given.

Thilashins often reside in either separate quarters or in segregated kyaung (temple-monasteries). They do not have to look after the monks, but may help cook if required. Although ranked lower than the monks, they are not subservient to them.

There have been efforts by some thilashins to reinstate the bhikkhuni lineage, although there are reservations from the government and general populace. A new Theravada bhikkhuni sangha was first convened in 1996, and since then many more have taken the full vows. However, within Myanmar, thilashins remain the only monastic option for women at this time. In 2003, Saccavadi and Gunasari were ordained as bhikkhunis in Sri Lanka, thus becoming the first female Myanma novices in modern times to receive higher ordination in Sri Lanka.[27][28]

Politics

Buddhism made major contributions in the development of Burmese politics. Burmese nationalism first began with the formation of the Young Men's Buddhist Associations (YMBA) - modelled on the YMCA - which started to appear all over the country at the start of the 20th century. Buddhist monks along with students had been in the forefront of the struggle for independence and later for democracy, the best known leaders in history being U Ottama and U Seinda in Rakhine State, and U Wisara who died after a protracted hunger strike in Yangon prison.[29][30] A major thoroughfare in Yangon is named after U Wisara. The League of Young Monks (ရဟန်းပျို Yahanpyo) based in Mandalay is a well known activist organisation. The Burmese word for boycott is thabeik hmauk (သပိတ်မှောက်), which literally means to turn the monk's alms bowl upside down - declining to accept alms in protest.[31]

Civilian governments, after the country gained independence, patronised Buddhism, donating large sums to fund the upkeep and building of Buddhist monuments. In addition, leaders of political parties and parliamentarians, in particular U Nu, passed legislation influenced by Buddhism. He declared Buddhism the state religion which alienated minority groups, especially the Kachin. This added yet another group to the growing number of ethnic insurgencies. The present military government has been so keen to be seen as patrons of Buddhism that it has become a joke- "Burmese TV has only two colours, green and yellow" - describing the military green uniforms and monk's yellow robes or golden pagodas which dominate the screen.

Shwedagon Pagoda has been an important venue for large public meetings where both Aung San and his daughter Aung San Suu Kyi had made their famous speeches. During the second university strike in history of 1936, the students camped out on the Shwedagon terraces.

Aung San Suu Kyi returned from London to lead the National League for Democracy which was founded during the 1988 popular uprising, but was placed under house arrest in 1989; since she is a devout Buddhist and leader of the opposition, she is considered a socially engaged Buddhist.

Saffron Revolution

In September 2007, Buddhists again took to the streets in the Saffron Revolution, a mass protest against the military government. Thousand of junta military and police forces poured into Yangon to try to control the situation, which rapidly deteriorated. A curfew was imposed and on 25 September troops surrounded Sule Pagoda. The protest continued to grow with regular citizens joining to support and defend the Buddhists. Overnight, junta forces invaded all the kyaungs in the country and imprisoned thousands of monks. It was reported that Nobel prize winning human rights activist and Buddhist Aung San Suu Kyi was removed from her home where she languished under house arrest and moved to the infamous Insein Prison. Mass protests erupted over this and junta troops began firing on monks, civilians, and demonstrators in the largest clash since 1988, which left thousands injured and hundreds dead. Images of the brutality were aired worldwide. Leaders around the world condemned the junta's actions and many nations imposed economic sanctions on Myanmar in protest. The President of the United States, George W. Bush, addressed the United Nations, stating, "Every civilized nation has a responsibility to stand up for people suffering under a brutal military regime like the one that has ruled Burma for so long." The Burmese junta responded by trying to control media coverage, curtail travel, censor news stories, and shut down access to the Internet.

In November 2008, U Gambira, a leader of the All Burma Monks' Alliance, was sentenced to 68 years in prison, at least 12 years of which will be hard labour; other charges against him are still pending.[32] In early 2009, his sentence was reduced to 63 years.[33] His sentence was protested by Human Rights Watch,[34] and Amnesty International considers him a prisoner of conscience.[35] Both groups called for his immediate release. Gambira was released during a mass pardon of prisoners on 13 January 2012 as part of the 2011–2012 Burmese political reforms. He ceased to be a monk in April 2012, stating that he had been unable to find a monastery to join due to his status as a former prisoner. He was re-arrested at least three times in 2012, and as of 11 December 2012, was released on bail.

See also

References

- Department of Population Ministry of Labour, Immigration and Population MYANMAR (July 2016). The 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census Census Report Volume 2-C. Department of Population Ministry of Labour, Immigration and Population MYANMAR. pp. 12–15.

- "The World Factbook".

- "Burma—International Religious Freedom Report 2009". U.S. Department of State. 26 October 2009. Archived from the original on 30 November 2009. Retrieved 11 November 2009.

- Cone & Gombrich, Perfect Generosity of Prince Vessantara, Oxford University Press, 1977, page xxii

- Pranke, Patrick A (2013), Myanmar, Encyclopedia of Buddhism, Macmillan Reference USA., ISBN 0-02-865718-7

- Ferguson, John P.; E. Michael Mendelson (1981). Masters of the Buddhist Occult: The Burmese Weikzas. Essays on Burma. Brill Archive. pp. 62–4. ISBN 978-90-04-06323-5.

- Sylvain Lévi, "Concept of Tribal Society" in Pfeffer, Georg; Behera, Deepak Kumar, eds. (2002). Concept of tribal society. New Delhi: Concept Pub. Co. ISBN 978-8170229834.

- Lieberman, Victor B (2003). Strange Parallels: Southeast Asia in Global Context, C. 800-1830, Volume 1: Integration on the Mainland. Cambridge University Press. pp. 115–116. ISBN 978-0-521-80496-7.

- Charney, Michael W. (2006) Powerful Learning. Buddhist Literati and the Throne in Burma's Last Dynasty, 1752-1885. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan. http://www.press.umich.edu/titleDetailDesc.do?id=225773

- "Introducing Myanmar Festivals". Yangon City Development Committee. Archived from the original on 14 June 2012. Retrieved 9 June 2007.

- Paw, Maung H. "Preparation for A Place of Worship At Home" (PDF). p. 4. Retrieved 28 February 2012.

- Ashin Kundalabhivamsa; Nibbana.com. "Words spoken by Lord Buddha on the day of Supreme Enlightenment-". Archived from the original on 13 October 2010. Retrieved 28 February 2012.

- Thanissaro Bhikkhu (1997). "Jaravagga: Aging". Access to Insight. Retrieved 28 February 2012.

- Swearer, Donald K. (2004). Becoming the Buddha: the ritual of image consecration in Thailand. Princeton University Press. pp. 218–219. ISBN 978-0-691-11435-4.

- Schober, Juliane (2002). Sacred biography in the Buddhist traditions of South and Southeast Asia. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 275–276. ISBN 978-81-208-1812-5.

- Htet Aung. "Save Our Schools". Irrawaddy 30 May 2007. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 3 June 2007.

- "The Account of Wazo Samgha of All Sect, M.E 1377 (2016)". The State Samgha Maha Nayaka Committee. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

- "Monks in Myanmar face tough odds". NBC News.

- "The Account of Wazo Monks and Nuns in 1377 (2016 year)". The State Samgha Maha Nayaka Committee. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

- "Shwegyin Nikaya". Archived from the original on 17 December 2008.

- "Dwara Nikaya". Archived from the original on 6 October 2006.

- "Hngettwin Nikaya". Archived from the original on 6 October 2006.

- Gutter, Peter (2001). "Law and Religion in Burma" (PDF). Legal Issues on Burma Journal. Burma Legal Council (8): 10. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 March 2012.

- Keown, Damien; Stephen Hodge; Paola Tinti (2003). A Dictionary of Buddhism. Oxford UP. pp. 98, 265, 266. ISBN 0-19-860560-9.

- Spiro, Melford (1982). Buddhism and society: a great tradition and its Burmese vicissitudes. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-04672-2.

- The Buddhist world of Southeast Asia By Donald K. Swearer

- Sujato, Bhante. "Saccavadi's story". Sujato’s Blog.

- Toomey, Christine (2016). "The Story of One Burmese Nun". Tricycle:The Buddhist Review. Retrieved 8 September 2019.

- Aung Zaw. "Burmese Monks in Revolt". The Irrawaddy 11 September 2007. Archived from the original on 11 October 2007. Retrieved 11 September 2007.

- Aung Zaw. "The Power Behind the Robe". The Irrawaddy 5 October 2007. Archived from the original on 6 February 2012. Retrieved 7 October 2007.

- "Associated Press: Monks put Myanmar junta in tight spot - Michael Casey". BurmaNet News 22 September 2007. Archived from the original on 13 December 2007. Retrieved 24 September 2007.

- "MYANMAR: Monk Receives 68 Years in Prison" (PDF). Amnesty International. 3 October 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 February 2011. Retrieved 20 April 2011.

- "The Resistance of the Monks". Human Rights Watch. 22 September 2009. Retrieved 20 April 2011.

- "Burma: End Repression of Buddhist Monks". Human Rights Watch. 22 September 2009. Retrieved 20 April 2011.

- "Myanmar, Unlock the Prison Doors!" (PDF). Amnesty International. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 May 2011. Retrieved 17 April 2011.

Further reading

- Aung-Thwin, Michael (1985). Pagan: The Origins of Modern Burma, University of Hawaii Press, Honolulu, ISBN 0824809602

- Bischoff, Roger (1995). Buddhism in Myanmar-A Short History, Kandy, Sri Lanka: Buddhist Publication Society. ISBN 955-24-0127-5

- Charney, Michael W. (2006). Powerful Learning. Buddhist Literati and the Throne in Burma's Last Dynasty, 1752-1885. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan. (Description)

- "The Constitution of the Union of Burma". DVB Multimedia Group. 1947. Archived from the original on 15 June 2006. Retrieved 7 July 2006.

- Ferguson, J.P. & Mendelson, E.M. (1981). "Masters of the Buddhist Occult: The Burmese Weikzas". Contributions to Asian Studies 16, pp. 62–88.

- Hlaing, Maung Myint (August 1981). The Great Disciples of Buddha. Zeyar Hlaing Literature House. pp. 66–68.

- Matthews, Bruce "The Legacy of Tradition and Authority: Buddhism and the Nation in Myanmar", in: Ian Harris (ed.), Buddhism and Politics in Twentieth-Century Asia. Continuum, London/New York 1999, pp. 26–53.

- Pranke, Patrick (1995), "On Becoming a Buddhist Wizard," in: Buddhism in Practice, ed. Donald S. Lopez, Jr., Princeton: Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-8121508322

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Buddhism in Myanmar. |

- Nibbana.com - Books and Articles by Myanmar Monks and Scholars for English-speaking Readers

- Buddhism in Myanmar BuddhaNet

- Buddhism in Myanmar G Appleton 1943

- Saddhamma Foundation Information about practising Buddhist meditation in Burma.

- The Life of the Buddha in 80 Scenes from the Ananda Temple,Bagan,Myanmar

- Buddha's Irresistible Maroon Army Dr Michael W Charney, SOAS, TIMESONLINE, 14 December 2007

- MyanmarNet Myanmar Yadanar Dhamma Section: Dhamma Video Talks in English or Myanmar by Venerable Myanmar Monks