Khmer language

Khmer (/kəˈmɛər/[5] or /kmɛər/;[6] natively ភាសាខ្មែរ phiăsaa khmae Khmer pronunciation: [pʰiə.ˈsaː kʰmae], dialectal khmæ or khmɛɛr, or more formally ខេមរភាសា kheemaʾraʾ phiăsaa Khmer pronunciation: [kʰeː.maʔ.raʔ pʰiə.ˈsaː]) is the language of the Khmer people and the official language of Cambodia. With approximately 16 million speakers, it is the second most widely spoken Austroasiatic language (after Vietnamese). Khmer has been influenced considerably by Sanskrit and Pali, especially in the royal and religious registers, through Hinduism and Buddhism. The more colloquial registers have influenced, and have been influenced by, Thai, Lao, Vietnamese, and Cham, all of which, due to geographical proximity and long-term cultural contact, form a sprachbund in peninsular Southeast Asia.[7] It is also the earliest recorded and earliest written language of the Mon–Khmer family, predating Mon and by a significant margin Vietnamese,[8] due to Old Khmer being the language of the historical empires of Chenla, Angkor and, presumably, their earlier predecessor state, Funan.

| Khmer | |

|---|---|

| Cambodian | |

| ភាសាខ្មែរ, phiăsaa khmae, ខ្មែរ, khmae | |

| Pronunciation | IPA: [pʰiə.ˈsaː kʰmae] |

| Native to | Cambodia, Vietnam, Thailand |

| Ethnicity | Khmer, Northern Khmer, Khmer Krom |

Native speakers | 16 million (2007)[1] |

Austroasiatic

| |

Early forms | Proto-Khmeric

|

| Dialects |

|

| Khmer script (abugida) Khmer Braille | |

| Official status | |

Official language in | |

Recognised minority language in | |

| Regulated by | Royal Academy of Cambodia |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | km Central Khmer |

| ISO 639-2 | khm Central Khmer |

| ISO 639-3 | Either:khm – Khmerkxm – Northern Khmer |

| Glottolog | khme1253 Khmeric[3]cent1989 Central Khmer[4] |

| Linguasphere | 46-FBA-a |

Khmer | |

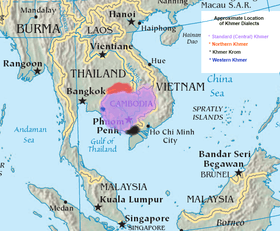

The vast majority of Khmer speakers speak Central Khmer, the dialect of the central plain where the Khmer are most heavily concentrated. Within Cambodia, regional accents exist in remote areas but these are regarded as varieties of Central Khmer. Two exceptions are the speech of the capital, Phnom Penh, and that of the Khmer Khe in Stung Treng province, both of which differ sufficiently enough from Central Khmer to be considered separate dialects of Khmer. Outside of Cambodia, three distinct dialects are spoken by ethnic Khmers native to areas that were historically part of the Khmer Empire. The Northern Khmer dialect is spoken by over a million Khmers in the southern regions of Northeast Thailand and is treated by some linguists as a separate language. Khmer Krom, or Southern Khmer, is the first language of the Khmer of Vietnam while the Khmer living in the remote Cardamom mountains speak a very conservative dialect that still displays features of the Middle Khmer language.

Khmer is primarily an analytic, isolating language. There are no inflections, conjugations or case endings. Instead, particles and auxiliary words are used to indicate grammatical relationships. General word order is subject–verb–object, and modifiers follow the word they modify. Classifiers appear after numbers when used to count nouns, though not always so consistently as in languages like Chinese. In spoken Khmer, topic-comment structure is common and the perceived social relation between participants determines which sets of vocabulary, such as pronouns and honorifics, are proper.

Khmer differs from neighboring languages such as Thai, Burmese, Lao and Vietnamese in that it is not a tonal language. Words are stressed on the final syllable, hence many words conform to the typical Mon–Khmer pattern of a stressed syllable preceded by a minor syllable. The language has been written in the Khmer script, an abugida descended from the Brahmi script via the southern Indian Pallava script, since at least the seventh century. The script's form and use has evolved over the centuries; its modern features include subscripted versions of consonants used to write clusters and a division of consonants into two series with different inherent vowels. Approximately 79% of Cambodians are able to read Khmer.[9]

Classification

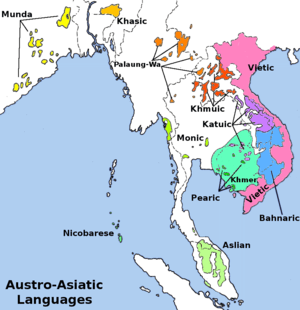

Khmer is a member of the Austroasiatic language family, the autochthonous family in an area that stretches from the Malay Peninsula through Southeast Asia to East India.[10] Austroasiatic, which also includes Mon, Vietnamese and Munda, has been studied since 1856 and was first proposed as a language family in 1907.[11] Despite the amount of research, there is still doubt about the internal relationship of the languages of Austroasiatic.[12] Diffloth places Khmer in an eastern branch of the Mon-Khmer languages.[13] In these classification schemes Khmer's closest genetic relatives are the Bahnaric and Pearic languages.[14] More recent classifications doubt the validity of the Mon-Khmer sub-grouping and place the Khmer language as its own branch of Austroasiatic equidistant from the other 12 branches of the family.[12]

Geographic distribution and dialects

Khmer is spoken by some 13 million people in Cambodia, where it is the official language. It is also a second language for most of the minority groups and indigenous hill tribes there. Additionally there are a million speakers of Khmer native to southern Vietnam (1999 census)[15] and 1.4 million in northeast Thailand (2006).[16]

Khmer dialects, although mutually intelligible, are sometimes quite marked. Notable variations are found in speakers from Phnom Penh (Cambodia's capital city), the rural Battambang area, the areas of Northeast Thailand adjacent to Cambodia such as Surin province, the Cardamom Mountains, and southern Vietnam.[17][18][19] The dialects form a continuum running roughly north to south. Standard Cambodian Khmer is mutually intelligible with the others but a Khmer Krom speaker from Vietnam, for instance, may have great difficulty communicating with a Khmer native of Sisaket Province in Thailand.

The following is a classification scheme showing the development of the modern Khmer dialects.[20][21]

- Middle Khmer

- Cardamom (Western) Khmer

- Central Khmer

- Surin (Northern) Khmer

- Standard Khmer and related dialects (including Khmer Krom)

Standard Khmer, or Central Khmer, the language as taught in Cambodian schools and used by the media, is based on the dialect spoken throughout the Central Plain,[22] a region encompassed by the northwest and central provinces.

Northern Khmer (called Khmer Surin in Khmer) refers to the dialects spoken by many in several border provinces of present-day northeast Thailand. After the fall of the Khmer Empire in the early 15th century, the Dongrek Mountains served as a natural border leaving the Khmer north of the mountains under the sphere of influence of the Kingdom of Lan Xang. The conquests of Cambodia by Naresuan the Great for Ayutthaya furthered their political and economic isolation from Cambodia proper, leading to a dialect that developed relatively independently from the midpoint of the Middle Khmer period.[23] This has resulted in a distinct accent influenced by the surrounding tonal languages Lao and Thai, lexical differences, and phonemic differences in both vowels and distribution of consonants. Syllable-final /r/, which has become silent in other dialects of Khmer, is still pronounced in Northern Khmer. Some linguists classify Northern Khmer as a separate but closely related language rather than a dialect.[24][25]

Western Khmer, also called Cardamom Khmer or Chanthaburi Khmer, is spoken by a very small, isolated population in the Cardamom mountain range extending from western Cambodia into eastern Central Thailand. Although little studied, this variety is unique in that it maintains a definite system of vocal register that has all but disappeared in other dialects of modern Khmer.[10]

Phnom Penh Khmer is spoken in the capital and surrounding areas. This dialect is characterized by merging or complete elision of syllables, which speakers from other regions consider a "relaxed" pronunciation. For instance, "Phnom Penh" is sometimes shortened to "m'Penh". Another characteristic of Phnom Penh speech is observed in words with an "r" either as an initial consonant or as the second member of a consonant cluster (as in the English word "bread"). The "r", trilled or flapped in other dialects, is either pronounced as a uvular trill or not pronounced at all. This alters the quality of any preceding consonant, causing a harder, more emphasized pronunciation. Another unique result is that the syllable is spoken with a low-rising or "dipping" tone much like the "hỏi" tone in Vietnamese. For example, some people pronounce /trəj/ ('fish') as [təj]: the /r/ is dropped and the vowel begins by dipping much lower in tone than standard speech and then rises, effectively doubling its length. Another example is the word /riən/ ('study'), which is pronounced [ʀiən], with the uvular "r" and the same intonation described above.[26]

Khmer Krom or Southern Khmer is spoken by the indigenous Khmer population of the Mekong Delta, formerly controlled by the Khmer Empire but part of Vietnam since 1698. Khmers are persecuted by the Vietnamese government for using their native language and, since the 1950s, have been forced to take Vietnamese names.[27] Consequently, very little research has been published regarding this dialect. It has been generally influenced by Vietnamese for three centuries and accordingly displays a pronounced accent, tendency toward monosyllablic words and lexical differences from Standard Khmer.[28]

Khmer Khe is spoken in the Se San, Srepok and Sekong river valleys of Sesan and Siem Pang districts in Stung Treng Province. Following the decline of Angkor, the Khmer abandoned their northern territories, which the Lao then settled. In the 17th century, Chey Chetha XI led a Khmer force into Stung Treng to retake the area. The Khmer Khe living in this area of Stung Treng in modern times are presumed to be the descendants of this group. Their dialect is thought to resemble that of pre-modern Siem Reap.[29]

Historical periods

| Old Khmer | |

|---|---|

| Angkorian Khmer | |

| ខ្មែរបុរាណ (khmae borean, khmer boran) (km) प्राचीन खमेर (praacheen khamer) (sa) | |

| Native to | Khmer Empire |

| Era | 9th to 14th century |

Austroasiatic

| |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | – |

| Glottolog | oldk1249[30] |

Linguistic study of the Khmer language divides its history into four periods one of which, the Old Khmer period, is subdivided into pre-Angkorian and Angkorian.[31] Pre-Angkorian Khmer, the Old Khmer language from 600 CE through 800, is only known from words and phrases in Sanskrit texts of the era. Old Khmer (or Angkorian Khmer) is the language as it was spoken in the Khmer Empire from the 9th century until the weakening of the empire sometime in the 13th century. Old Khmer is attested by many primary sources and has been studied in depth by a few scholars, most notably Saveros Pou, Phillip Jenner and Heinz-Jürgen Pinnow. Following the end of the Khmer Empire the language lost the standardizing influence of being the language of government and accordingly underwent a turbulent period of change in morphology, phonology and lexicon. The language of this transition period, from about the 14th to 18th centuries, is referred to as Middle Khmer and saw borrowing from Thai, Lao and, to a lesser extent, Vietnamese. The changes during this period are so profound that the rules of Modern Khmer can not be applied to correctly understand Old Khmer. The language became recognizable as Modern Khmer, spoken from the 19th century till today.[31]

The following table shows the conventionally accepted historical stages of Khmer.[20]

| Historical stage | Date |

|---|---|

| Pre- or Proto-Khmer | Before 600 CE |

| Pre-Angkorian Old Khmer | 600–800 |

| Angkorian Old Khmer | 800 to mid-14th century |

| Middle Khmer | Mid-14th century to 18th century |

| Modern Khmer | 1800–present |

Just as modern Khmer was emerging from the transitional period represented by Middle Khmer, Cambodia fell under the influence of French colonialism.[32] Thailand, which had for centuries claimed suzerainty over Cambodia and controlled succession to the Cambodian throne, began losing its influence on the language.[33] In 1887 Cambodia was fully integrated into French Indochina, which brought in a French-speaking aristocracy. This led to French becoming the language of higher education and the intellectual class. By 1907, the French had wrested over half of modern-day Cambodia, including the north and northwest where Thai had been the prestige language, back from Thai control and reintegrated it into the country.[33]

Many native scholars in the early 20th century, led by a monk named Chuon Nath, resisted the French and Thai influences on their language. Forming the government sponsored Cultural Committee to define and standardize the modern language, they championed Khmerization, purging of foreign elements, reviving affixation, and the use of Old Khmer roots and historical Pali and Sanskrit to coin new words for modern ideas.[32][34] Opponents, led by Keng Vannsak, who embraced "total Khmerization" by denouncing the reversion to classical languages and favoring the use of contemporary colloquial Khmer for neologisms, and Ieu Koeus, who favored borrowing from Thai, were also influential.[34] Koeus later joined the Cultural Committee and supported Nath. Nath's views and prolific work won out and he is credited with cultivating modern Khmer-language identity and culture, overseeing the translation of the entire Pali Buddhist canon into Khmer. He also created the modern Khmer language dictionary that is still in use today, thereby ensuring that Khmer would survive, and indeed flourish, during the French colonial period.[32]

Phonology

| Khmer language |

|---|

|

| Khmer language |

|

| Dialects |

|

The phonological system described here is the inventory of sounds of the standard spoken language,[22] represented using appropriate symbols from the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA).

Consonants

| Labial | Alveolar | Palatal | Velar | Glottal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plosive | p (pʰ) | t (tʰ) | c (cʰ) | k (kʰ) | ʔ |

| Voiced plosive/Implosive | ɓ ~ b | ɗ ~ d | |||

| Nasal | m | n | ɲ | ŋ | |

| Liquid | r l | ||||

| Fricative | s | h | |||

| Approximant | ʋ ~ w | j |

The voiceless plosives /p/, /t/, /c/, /k/ may occur with or without aspiration (as [p] vs. [pʰ], etc.); this difference is contrastive before a vowel. However, the aspirated sounds in that position may be analyzed as sequences of two phonemes: /ph/, /th/, /ch/, /kh/. This analysis is supported by the fact that infixes can be inserted between the stop and the aspiration; for example [tʰom] ('big') becomes [tumhum] ('size') with a nominalizing infix. When one of these plosives occurs initially before another consonant, aspiration is no longer contrastive and can be regarded as mere phonetic detail:[35][36] slight aspiration is expected when the following consonant is not one of /ʔ/, /b/, /d/, /r/, /s/, /h/ (or /ŋ/ if the initial plosive is /k/).

The voiced plosives are pronounced as implosives [ɓ, ɗ] by most speakers, but this feature is weak in educated speech, where they become [b, d].[37]

In syllable-final position, /h/ and /ʋ/ approach [ç] and [w] respectively. The stops /p/, /t/, /c/, /k/ are unaspirated and have no audible release when occurring as syllable finals.[22]

In addition, the consonants /ɡ/, /f/, /ʃ/ and /z/ occur occasionally in recent loan words in the speech of Cambodians familiar with French and other languages.

Vowels

Various authors have proposed slightly different analyses of the Khmer vowel system. This may be in part because of the wide degree of variation in pronunciation between individual speakers, even within a dialectal region.[38] The description below follows Huffman (1970).[22] The number of vowel nuclei and their values vary between dialects; differences exist even between the Standard Khmer system and that of the Battambang dialect on which the standard is based.[39]

| Front | Central | Back | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| short | long | short | long | short | long | |

| Close | i | iː | ɨ | ɨː | u | uː |

| Close-mid | e | eː | ə | əː | o | oː |

| Open-mid | ɛː | ɔː | ||||

| Open | a | aː | ɑ | ɑː | ||

| Long diphthongs | iə | ei | ae | ɨə | əɨ | aə | uə | ou | ao | ɔə |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Short diphthongs | ĕə | ŭə | ŏə |

In addition, some diphthongs and triphthongs are analyzed as a vowel nucleus plus a semivowel (/j/ or /w/) coda because they cannot be followed by a final consonant. These include: (with short monophthongs) /ɨw/, /əw/, /aj/, /aw/, /uj/; (with long monophthongs) /əːj/, /aːj/; (with long diphthongs) /iəj/, /iəw/, /ɨəj/, /aoj/, /aəj/ and /uəj/.[40]

Syllable structure

A Khmer syllable begins with a single consonant, or else with a cluster of two, or rarely three, consonants. The only possible clusters of three consonants at the start of a syllable are /str/, /skr/,[41] and (with aspirated consonants analyzed as two-consonant sequences) /sth/, /lkh/. There are 85 possible two-consonant clusters (including [pʰ] etc. analyzed as /ph/ etc.). All the clusters are shown in the following table, phonetically, i.e. superscript ʰ can mark either contrastive or non-contrastive aspiration (see above).

| p | ɓ | t | ɗ | c | k | ʔ | m | n | ɲ | ŋ | j | l | r | s | h | ʋ | t+h | k+h | t+r | k+r | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p | pʰt- | pɗ- | pʰc- | pʰk- | pʔ- | pʰn- | pʰɲ- | pʰŋ- | pʰj- | pʰl- | pr- | ps- | pʰ- | ||||||||

| t | tʰp- | tɓ- | tʰk- | tʔ- | tʰm- | tʰn- | tʰŋ- | tʰj- | tʰl- | tr- | tʰ- | tʰʋ- | |||||||||

| c | cʰp- | cɓ- | cɗ- | cʰk- | cʔ- | cʰm- | cʰn- | cʰŋ- | cʰl- | cr- | cʰ- | cʰʋ- | |||||||||

| k | kʰp- | kɓ- | kʰt- | kɗ- | kʰc- | kʔ- | kʰm- | kʰn- | kʰɲ- | kŋ- | kʰj- | kʰl- | kr- | ks- | kʰ- | kʰʋ- | |||||

| s | sp- | sɓ- | st- | sɗ- | sk- | sʔ- | sm- | sn- | sɲ- | sŋ- | sl- | sr- | sʋ- | stʰ- | str- | skr- | |||||

| ʔ | ʔʋ- | ||||||||||||||||||||

| m | mt- | mɗ- | mc- | mʔ- | mn- | mɲ- | ml- | mr- | ms- | mh- | |||||||||||

| l | lp- | lɓ- | lk- | lʔ- | lm- | lŋ- | lh- | lʋ- | lkʰ- |

Slight vowel epenthesis occurs in the clusters consisting of a plosive followed by /ʔ/, /b/, /d/, in those beginning /ʔ/, /m/, /l/, and in the cluster /kŋ-/.[42]:8–9

After the initial consonant or consonant cluster comes the syllabic nucleus, which is one of the vowels listed above. This vowel may end the syllable or may be followed by a coda, which is a single consonant. If the syllable is stressed and the vowel is short, there must be a final consonant. All consonant sounds except /b/, /d/, /r/, /s/ and the aspirates can appear as the coda (although final /r/ is heard in some dialects, most notably in Northern Khmer).[43]

A minor syllable (unstressed syllable preceding the main syllable of a word) has a structure of CV-, CrV-, CVN- or CrVN- (where C is a consonant, V a vowel, and N a nasal consonant). The vowels in such syllables are usually short; in conversation they may be reduced to [ə], although in careful or formal speech, including on television and radio, they are clearly articulated. An example of such a word is មនុស្ស mɔnuh, mɔnɨh, mĕəʾnuh ('person'), pronounced [mɔˈnuh], or more casually [məˈnuh].[42]:10

Stress

Stress in Khmer falls on the final syllable of a word.[44] Because of this predictable pattern, stress is non-phonemic in Khmer (it does not distinguish different meanings).

Most Khmer words consist of either one or two syllables. In most native disyllabic words, the first syllable is a minor (fully unstressed) syllable. Such words have been described as sesquisyllabic (i.e. as having one-and-a-half syllables). There are also some disyllabic words in which the first syllable does not behave as a minor syllable, but takes secondary stress. Most such words are compounds, but some are single morphemes (generally loanwords). An example is ភាសា ('language'), pronounced [ˌpʰiəˈsaː].[42]:10

Words with three or more syllables, if they are not compounds, are mostly loanwords, usually derived from Pali, Sanskrit, or more recently, French. They are nonetheless adapted to Khmer stress patterns.[45] Primary stress falls on the final syllable, with secondary stress on every second syllable from the end. Thus in a three-syllable word, the first syllable has secondary stress; in a four-syllable word, the second syllable has secondary stress; in a five-syllable word, the first and third syllables have secondary stress, and so on.[42]:10–11 Long polysyllables are not often used in conversation.[22]:12

Compounds, however, preserve the stress patterns of the constituent words. Thus សំបុកចាប, the name of a kind of cookie (literally 'bird's nest'), is pronounced [sɑmˌbok ˈcaːp], with secondary stress on the second rather than the first syllable, because it is composed of the words [sɑmˈbok] ('nest') and [caːp] ('bird').[45]

Phonation and tone

Khmer once had a phonation distinction in its vowels, but this now survives only in the most archaic dialect (Western Khmer).[10] The distinction arose historically when vowels after Old Khmer voiced consonants became breathy voiced and diphthongized; for example *kaa, *ɡaa became *kaa, *ɡe̤a. When consonant voicing was lost, the distinction was maintained by the vowel (*kaa, *ke̤a); later the phonation disappeared as well ([kaː], [kiə]).[35] These processes explain the origin of what are now called a-series and o-series consonants in the Khmer script.

Although most Cambodian dialects are not tonal, the colloquial Phnom Penh dialect has developed a tonal contrast (level versus peaking tone) as a by-product of the elision of /r/.[35]

Intonation

Intonation often conveys semantic context in Khmer, as in distinguishing declarative statements, questions and exclamations. The available grammatical means of making such distinctions are not always used, or may be ambiguous; for example, the final interrogative particle ទេ /teː/ can also serve as an emphasizing (or in some cases negating) particle.[46]

The intonation pattern of a typical Khmer declarative phrase is a steady rise throughout followed by an abrupt drop on the last syllable.[41]

- ខ្ញុំមិនចង់បានទេ [↗kʰɲom mɨn cɒŋ baːn | ↘teː] ('I don't want it')[41]

Other intonation contours signify a different type of phrase such as the "full doubt" interrogative, similar to yes-no questions in English. Full doubt interrogatives remain fairly even in tone throughout, but rise sharply towards the end.

- អ្នកចង់ទៅលេងសៀមរាបទេ [↗neaʔ caŋ | ↗tɨw leːŋ siəm riəp | ꜛteː] ('do you want to go to Siem Reap?')[41]

Exclamatory phrases follow the typical steadily rising pattern, but rise sharply on the last syllable instead of falling.[41]

- សៀវភៅនេះថ្លៃណាស់ [↗siəw pʰɨw nih| ↗tʰlaj | ꜛnah] ('this book is expensive!')[41]

Grammar

Khmer is primarily an analytic language with no inflection. Syntactic relations are mainly determined by word order. Old and Middle Khmer used particles to mark grammatical categories and many of these have survived in Modern Khmer but are used sparingly, mostly in literary or formal language.[46] Khmer makes extensive use of auxiliary verbs, "directionals" and serial verb construction. Colloquial Khmer is a zero copula language, instead preferring predicative adjectives (and even predicative nouns) unless using a copula for emphasis or to avoid ambiguity in more complex sentences. Basic word order is subject–verb–object (SVO), although subjects are often dropped; prepositions are used rather than postpositions.[47] Topic-Comment constructions are common and the language is generally head-initial (modifiers follow the words they modify). Some grammatical processes are still not fully understood by western scholars. For example, it is not clear if certain features of Khmer grammar, such as actor nominalization, should be treated as a morphological process or a purely syntactic device,[48]:46, 74 and some derivational morphology seems "purely decorative" and performs no known syntactic work.[48]:53

Lexical categories have been hard to define in Khmer.[48]:360 Henri Maspero, an early scholar of Khmer, claimed the language had no parts of speech,[48] while a later scholar, Judith Jacob, posited four parts of speech and innumerable particles.[49]:331 John Haiman, on the other hand, identifies "a couple dozen" parts of speech in Khmer with the caveat that Khmer words have the freedom to perform a variety of syntactic functions depending on such factors as word order, relevant particles, location within a clause, intonation and context.[48] Some of the more important lexical categories and their function are demonstrated in the following example sentence taken from a hospital brochure:[48]:378

/loːk

PRONOUN

you[RESP]

nĕəʔ

PRONOUN

you[FAM]

pdɑl

VERB

provide

cʰiəm

NOUN

blood

tĕəŋ

PARTICLE

every

ʔɑh

ADJECTIVE

all

trəw

AUXILIARY VERB

must

tae

INTENSIFIER

have to

tɔtuəl

VERB

receive

nəw

OBJECT MARKER

kaː

NOMINALIZER

piːnɨt

VERB

examine

riəŋ

NOUN

shape

kaːj

NOUN

body

nɨŋ

CONJUNCTION

and

pdɑl

VERB

provide

nəw

OBJECT MARKER

prɑʋŏət

NOUN

history

sokʰapʰiəp

ADJECTIVE

health

ciə

COPULA

be

mun

ADVERB

before

ciə

COPULA

be

sən/

ADVERB

first

'All blood donors must pass a physical examination and provide a health history first (before they can give blood).'

Morphology

Modern Khmer is an isolating language, which means that it uses little productive morphology. There is some derivation by means of prefixes and infixes, but this is a remnant of Old Khmer and not always productive in the modern language.[50] Khmer morphology is evidence of a historical process through which the language was, at some point in the past, changed from being an agglutinative language to adopting an isolating typology.[51] Affixed forms are lexicalized and cannot be used productively to form new words.[42]:311 Below are some of the most common affixes with examples as given by Huffman.[42]:312–316

| Affix | Function | Word | Meaning | Affixed Word | Meaning |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| prefixed /p/ | causation | /dac/ /daəm/ | "broke, torn" "origin" | /pdac/ /pdaəm/ | "to tear apart" "to originate (trans.)" |

| prefixed /rɔ/ | derives adjectives nominalization | /lŭət/ /baŋ/ | "to extinguish" "to hide" | /rɔlŭət/ /rɔbaŋ/ | "extinguished" "a screen, shade" |

| prefixed /prɑ/ | reciprocity | /kʰam/ /douc/ | "to bite" "similar" | /prɑkʰam/ /prɑdouc/ | "to bite each other" "to compare" |

| prefixed /bɑN/ | causation | /baek/ /daə/ /riən/ | "to break (intrans.)" "to walk" "to study, learn" | /bɑmbaek/ /bɑndaə/ /bɑŋriən/ | "to cause to break" "to take for a walk" "to teach" |

| infixed /ɑm/ | causation | /sʔaːt/ /slap/ | "to be clean" "to die" | /sɑmʔaːt/ /sɑmlap/ | "to clean" "to kill" |

| infixed /Vmn/ | nominalization | /daə/ /dəŋ/ /cɨə/ | "to walk" "to know (something)" "to believe" | /dɑmnaə/ /dɑmnəŋ/ /cumnɨə/ | "a trip" "information" "belief" |

Compounding in Khmer is a common derivational process that takes two forms, coordinate compounds and repetitive compounds. Coordinate compounds join two unbound morphemes (independent words) of similar meaning to form a compound signifying a concept more general than either word alone.[42]:296 Coordinate compounds join either two nouns or two verbs. Repetitive compounds, one of the most productive derivational features of Khmer, use reduplication of an entire word to derive words whose meaning depends on the class of the reduplicated word.[42]:185 A repetitive compound of a noun indicates plurality or generality while that of an adjectival verb could mean either an intensification or plurality.

Coordinate compounds:[42]:296–297

/ʔəwpuk/ + /mdaːj/ ⇒ /ʔəwpuk mdaːj/ 'father' 'mother' ⇒ 'parents' /dək/ + /nŏəm/ ⇒ /dək nŏəm/ 'to transport' 'to carry' ⇒ 'to lead'

Repetitive compounds:[42]:185–185

/cʰap/ ⇒ /cʰap cʰap/ /srəj/ ⇒ /srəj srəj/ 'fast' 'very fast, quickly' 'women' 'women, women in general'

Nouns and pronouns

Khmer nouns do not inflect for grammatical gender or singular/plural. There are no articles, but indefiniteness is often expressed by the word for "one" (មួយ, /muəj/) following the noun as in ឆ្កែមួយ (/cʰkae muəj/ "a dog"). Plurality can be marked by postnominal particles, numerals, or reduplication of a following adjective, which, although similar to intensification, is usually not ambiguous due to context.[52]

/cʰkae craən/ or /cʰkae piː/ or /cʰkae tʰom tʰom/ dog many dog two dog large large 'many dogs' 'two dogs' 'large dogs'

Classifying particles are used after numerals, but are not always obligatory as they are in Thai or Chinese, for example, and are often dropped in colloquial speech. Khmer nouns are divided into two groups: mass nouns, which take classifiers; and specific, nouns, which do not. The overwhelming majority are mass nouns.[42]:67–68

/kʰmaw.daj piː daəm/ pencil two long cylindrical object[clf] 'two pencils'

Possession is colloquially expressed by word order. The possessor is placed after the thing that is possessed.[48]:160 Alternatively, in more complex sentences or when emphasis is required, a possessive construction using the word របស់ (/rɔbɑh/ ~ /ləbɑh/, "property, object") may be employed. In formal and literary contexts, the possessive particle នៃ (nɨj) is used:[42]:358

/puəʔmaːʔ kʰɲom/ or /puəʔmaːʔ rɔbɑh kʰɲom/ or /puəʔmaːʔ nɨj kʰɲom/ friend I friend property I friend poss I 'my friend' 'my friend' 'my friend'

Pronouns are subject to a complicated system of social register, the choice of pronoun depending on the perceived relationships between speaker, audience and referent (see Social registers below). Kinship terms, nicknames and proper names are often used as pronouns (including for the first person) among intimates. Subject pronouns are frequently dropped in colloquial conversation.[52]

Adjectives, verbs and verb phrases may be made into nouns by the use of nominalization particles. Three of the more common particles used to create nouns are /kaː/, /sec kdəj/, and /pʰiəp/.[48]:45–48 These particles are prefixed most often to verbs to form abstract nouns. The latter, derived from Sanskrit, also occurs as a suffix in fixed forms borrowed from Sanskrit and Pali such as /sokʰa.pʰiəp/ ("health") from /sok/ ("to be healthy").[45]

/kaː rŭəhnɨw/ /sec kdəj deik/ /pʰiəp sɑːm rum' nmlz to live nmlz to lie down nmlz appropriate 'life' '[the act of] lying down' 'appropriateness'[48]

Adjectives and adverbs

Adjectives, demonstratives and numerals follow the noun they modify. Adverbs likewise follow the verb. Morphologically, adjectives and adverbs are not distinguished, with many words often serving either function. Adjectives are also employed as verbs as Khmer sentences rarely use a copula.[42]

Degrees of comparison are constructed syntactically. Comparatives are expressed using the word ជាង /ciəŋ/: "A X /ciəŋ/ [B]" (A is more X [than B]). The most common way to express superlatives is with ជាងគេ /ciəŋ keː/: "A X /ciəŋ keː/" (A is the most X).[52] Intensity is also expressed syntactically, similar to other languages of the region, by reduplication or with the use of intensifiers.[52]

/srəj nuh/ sʔaːt/ /srəj nuh sʔaːt sʔaːt/ /srəj nuh sʔaːt nah/ girl dem pretty girl dem pretty pretty girl dem pretty very 'That girl is pretty.' 'That girl is very pretty.' 'That girl is very pretty.'

Verbs

As is typical of most East Asian languages,[53] Khmer verbs do not inflect at all; tense, aspect and mood can be expressed using auxiliary verbs, particles (such as កំពុង /kəmpuŋ/, placed before a verb to express continuous aspect) and adverbs (such as "yesterday", "earlier", "tomorrow"), or may be understood from context. Serial verb construction is quite common.[48]:253

Khmer verbs are a relatively open class and can be divided into two types, main verbs and auxiliary verbs.[48]:254 Huffman defined a Khmer verb as "any word that can be (negated)",[42]:56 and further divided main verbs into three classes.

Transitive verbs are verbs that may be followed by a direct object:

/kʰɲom ɲam baj/ /kʰɲom tɨɲ baːrəj/ I eat rice I buy cigarettes 'I eat rice.' 'I buy cigarettes.'

Intransitive verbs are verbs that can not be followed by an object:

/kʰɲom daə tɨw pʰsaː/ /ʔaɲcəɲ ʔɑŋkuj/ I walk directional market to invite to sit 'I walk to the market.' 'Please sit.'

Adjectival verbs are a word class that has no equivalent in English. When modifying a noun or verb, they function as adjectives or adverbs, respectively, but they may also be used as main verbs equivalent to English "be + adjective".

Adjective: /proh lʔɑː/ boy handsome 'handsome boy' Adverb: /proh nuh tʰʋəː kaː lʔɑː/ boy dem to work good 'That boy works well.' Verb: /proh nuh lʔɑː/ boy dem handsome 'That boy is handsome.'[42]:56

Syntax

Syntax is the rules and processes that describe how sentences are formed in a particular language, how words relate to each other within clauses or phrases and how those phrases relate to each other within a sentence to convey meaning.[54] Khmer syntax is very analytic. Relationships between words and phrases are signified primarily by word order supplemented with auxiliary verbs and, particularly in formal and literary registers, grammatical marking particles.[48] Grammatical phenomena such as negation and aspect are marked by particles while interrogative sentences are marked either by particles or interrogative words equivalent to English "wh-words".

A complete Khmer sentence consists of four basic elements—an optional topic, an optional subject, an obligatory predicate, and various adverbials and particles.[55] The topic and subject are noun phrases, predicates are verb phrases and another noun phrase acting as an object or verbal attribute often follows the predicate.[55]

Basic constituent order

When combining these noun and verb phrases into a sentence the order is typically SVO:

/kʰɲom ʔaoj ceik muəj cɑmnuən/ sbj verb obj I give banana one bunch[clf] 'I gave a bunch of bananas.'

When both a direct object and indirect object are present without any grammatical markers, the preferred order is SV(DO)(IO). In such a case, if the direct object phrase contains multiple components, the indirect object immediately follows the noun of the direct object phrase and the direct object's modifiers follow the indirect object:

/kʰɲom ʔaoj ceik cruːk muəj cɑmnuən/ sbj verb dir obj ind obj I give banana pig one bunch[clf] 'I gave the pig a bunch of bananas.'[48]:207

This ordering of objects can be changed and the meaning clarified with the inclusion of particles. The word /dɑl/, which normally means "to arrive" or "towards", can be used as a preposition meaning "to":

/kʰɲom ʔaoj ceik muəj cɑmnuən dɑl cruːk/ I give banana one bunch[clf] toward pig 'I gave a bunch of bananas to the pigs.'[48]:207

Alternatively, the indirect object could precede the direct object if the object-marking preposition /nəw/ were used:

/kʰɲom ʔaoj cruːk nəw ceik muəj cɑmnuən/ I give pig obj marker banana one bunch[clf] 'I gave the pig a bunch of bananas.'[48]:207

However, in spoken discourse OSV is possible when emphasizing the object in a topic–comment-like structure.[48]:211

Noun phrase

The noun phrase in Khmer typically has the following structure:[42]:50–51[49]:83

- Noun Phrase = (Honorific) Noun (Adjectival modifiers) (Numeral) (Classifier) (Demonstrative)

The elements in parentheses are optional. Honorifics are a class of words that serve to index the social status of the referent. Honorifics can be kinship terms or personal names, both of which are often used as first and second person pronouns, or specialized words such as /preah/ ('god') before royal and religious objects.[48]:155 The most common demonstratives are /nih/ ('this, these') and /nuh/ ('that, those'). The word /ae nuh/ ('those over there') has a more distal or vague connotation.[45] If the noun phrase contains a possessive adjective, it follows the noun and precedes the numeral. If a descriptive attribute co-occurs with a possessive, the possessive construction (/rɔbɑh/) is expected.[42]:73

Some examples of typical Khmer noun phrases are:

Khmer text IPA gloss translation ផ្ទះស្កឹមស្កៃបីបួនខ្នងនេះ /ptĕəh skəm.skaj bəj buən kʰnɑːŋ nih/ house high three four spine[clf] these

noun adj num num classifier dem'these three or four high houses'[48]:142 ចេកទុំពីរស្និតនេះ /ceːk tum piː snət nih/ banana ripe two bunches[clf] these

noun adj num classifier demthese two bunches of ripe bananas ពួកម៉ាកខ្ញុំពីរនាក់នេះ /puəʔmaʔ kʰɲom piː nĕə nih/ friend I two person[clf] these

noun poss num classifier demthese two friends of mine ពួកម៉ាកតូចរបស់ខ្ញុំពីរនាក់នេះ /puəʔmaʔ touc rɔbɑh kʰɲom piː nĕə nih/ friend small of I two person[clf] these

noun adj poss num classifier demthese two small friends of mine[42]:73

The Khmer particle /dɑː/ marked attributes in Old Khmer noun phrases and is used in formal and literary language to signify that what precedes is the noun and what follows is the attribute. Modern usage may carry the connotation of mild intensity.[48]:163

/ʋiəl srae dɑː lʋɨŋ lʋəːj/ field paddy adj marker vast '(very) expansive fields and paddies'

Verb phrase

Khmer verbs are completely uninflected, and once a subject or topic has been introduced or is clear from context the noun phrase may be dropped. Thus, the simplest possible sentence in Khmer consists of a single verb. For example, /tɨw/ 'to go' on its own can mean "I'm going.", "He went.", "They've gone.", "Let's go.", etc.[42]:17 This also results in long strings of verbs such as:

/kʰɲom cɑng tɨw daə leːng/ I to want to go to walk to play 'I want to go for a stroll.'[42]:187

Khmer uses three verbs for what translates into English as the copula. The general copula is /ciə/; it is used to convey identity with nominal predicates.[48]:212 For locative predicates, the copula is /nɨw/.[48]:212 The verb /miən/ is the "existential" copula meaning "there is" or "there exists".[48]:208

/piəsaː ciə kaː sɑmdaeŋ cət kumnɨt krŏəp jaːŋ/ language copula nmlz to express heart thought all kind 'Language is the expression of all emotions and ideas' /ʋiə nɨw cɪt ʋŏət/ /miən pʰaen kaː/ he copula close temple to exist plan 'He is close to the temple.' 'There is a plan.'

Negation is achieved by putting មិន /mɨn/ before the verb and the particle ទេ /teː/ at the end of the sentence or clause. In colloquial speech, verbs can also be negated without the need for a final particle, by placing ឥត /ʔɑt/~/ʔət/ before them.[52]

/kʰɲom cɨə/ /kʰɲom mɨn cɨə teː/ /kʰɲom ʔɑt cɨə/ I to believe I neg to believe neg I neg to believe 'I believe.' 'I don't believe.' 'I don't believe.'

Past tense can be conveyed by adverbs, such as "yesterday" or by the use of perfective particles such as /haəj/

/kŏət tɨw msəlmɨɲ/ /kŏət tɨw haəj/ he to go yesterday he to go pfv 'He went yesterday.' 'He left.' or 'He's already gone.'[42]:22

Different senses of future action can also be expressed by the use of adverbs like "tomorrow" or by the future tense marker /nɨŋ/, which is placed immediately before the verb, or both:

/sʔaek kʰɲom nɨŋ tɨw saːlaː riən/ tomorrow I fut to go school 'Tomorrow, I will go to school.'[45]

Imperatives are often unmarked.[48]:240 For example, in addition to the meanings given above, the "sentence" /tɨw/ can also mean "Go!". Various words and particles may be added to the verb to soften the command to varying degrees, including to the point of politeness (jussives):[48]:240

/cou saːk lbɑːŋ kʰluən aeŋ coh/ /soum tʰʋəː taːm bɑndam kŏət tɨw/ imp try try you refl imp please do follow instruction he imp 'Go ahead and try it yourself.' 'Please follow his instructions.'

Prohibitives take the form "/kom/ + verb" and also are often softened by the addition of the particle /ʔəj/ to the end of the phrase.[48]:242

/kom nɨw tiː nih ʔəj/ proh to be place dem cohortative 'Don't stay in this place.'

Questions

There are three basic types of questions in Khmer.[42]:46 Questions requesting specific information use question words. Polar questions are indicated with interrogative particles, most commonly /teː/, a homonym of the negation particle. Tag questions are indicated with various particles and rising inflection.[42]:57 The SVO word order is generally not inverted for questions.

/loːk tɨw naː/ /loːk sdap baːn teː/ /loːk tɨw psaː haəj rɨː nɨw/ you to go where you understand modal q you to go market prf or yet 'Where are you going?' 'Can you understand?' 'Have you gone to the store yet?'

In more formal contexts and in polite speech, questions are also marked at their beginning by the particle /taə/.

/taə loːk ʔɑɲcəːɲ tɨw naː/ q you to invite to go where 'Where are you going, sir?'[42]:302

Passive voice

Khmer does not have a passive voice,[46] but there is a construction utilizing the main verb /trəw/ ("to hit", "to be correct", "to affect") as an auxiliary verb meaning "to be subject to" or "to undergo"—which results in sentences that are translated to English using the passive voice.[48]:286–288

/piː msəlmɨɲ kʰɲom trəw cʰkae kʰam/ from yesterday I to undergo dog to bite 'Yesterday I was bitten by a dog.'[42]:302

Clause syntax

Complex sentences are formed in Khmer by the addition of one or more clauses to the main clause. The various types of clauses in Khmer include the coordinate clause, the relative clause and the subordinate clause. Word order in clauses is the same for that of the basic sentences described above.[48] Coordinate clauses do not necessarily have to be marked; they can simply follow one another. When explicitly marked, they are joined by words similar to English conjunctions such as /nɨŋ/ ("and") and /haəj/ ("and then") or by clause-final conjunction-like adverbs /dae/ and /pʰɑːŋ/, both of which can mean "also" or "and also"; disjunction is indicated by /rɨː/ ("or").[48]:217–218[56] Relative clauses can be introduced by /dael/ ("that") but, similar to coordinate clauses, often simply follow the main clause. For example, both phrases below can mean "the hospital bed that has wheels".[48]:313

/krɛː pɛːt miən kɑŋ ruɲ/ /krɛː pɛːt dael miən kɑŋ ruɲ/ bed hospital have wheel to push bed hospital rel have wheel to push

Relative clauses are more likely to be introduced with /dael/ if they do not immediately follow the head noun.[48]:314 Khmer subordinate conjunctions always precede a subordinate clause.[48]:366 Subordinate conjunctions include words such as /prŭəh/ ("because"), /hak bəj/ ("seems as if") and /daəmbəj/ ("in order to").[42]:251[48]

Numerals

Counting in Khmer is based on a biquinary system (the numbers from 6 to 9 have the form "five one", "five two", etc.) However, the words for multiples of ten from 30 to 90 are not related to the basic Khmer numbers, but are probably borrowed from Thai. Khmer numerals, which were inherited from Indian numerals, are used more widely than Western Arabic numerals.

The principal number words are listed in the following table, which gives Western and Khmer digits, Khmer spelling and IPA transcription.[50]

| 0 | ០ | សូន្យ | /soun/ | ||||

| 1 | ១ | មួយ | /muəj/ | ||||

| 2 | ២ | ពីរ | /piː/ | 20 | ២០ | ម្ភៃ | /məˈphɨj/ |

| 3 | ៣ | បី | /ɓəj/ | 30 | ៣០ | សាមសិប | /saːm səp/ |

| 4 | ៤ | បួន | /ɓuən/ | 40 | ៤០ | សែសិប | /sae səp/ |

| 5 | ៥ | ប្រាំ | /pram/ | 50 | ៥០ | ហាសិប | /haː səp/ |

| 6 | ៦ | ប្រាំមូយ | /pram muəj/ | 60 | ៦០ | ហុកសិប | /hok səp/ |

| 7 | ៧ | ប្រាំពីរ | /pram piː/, /pram pɨl/ | 70 | ៧០ | ចិតសិប | /cət səp/ |

| 8 | ៨ | ប្រាំបី | /pram ɓəj/ | 80 | ៨០ | ប៉ែតសិប | /paet səp/ |

| 9 | ៩ | ប្រាំបួន | /pram ɓuən/ | 90 | ៩០ | កៅសិប | /kaʋ səp/ |

| 10 | ១០ | ដប់ | /ɗɑp/ | 100 | ១០០ | មួយរយ | /muəj rɔːj/ |

Intermediate numbers are formed by compounding the above elements. Powers of ten are denoted by loan words: រយ /rɔːj/ (100), ពាន់ /pŏən/ (1,000), ម៉ឺន /məɨn/ (10,000), សែន /saen/ (100,000) and លាន /liən/ (1,000,000) from Thai and កោដិ /kaot/ (10,000,000) from Sanskrit.[57]

Ordinal numbers are formed by placing the particle ទី /tiː/ before the corresponding cardinal number.[45]

Social registers

Khmer employs a system of registers in which the speaker must always be conscious of the social status of the person spoken to. The different registers, which include those used for common speech, polite speech, speaking to or about royals and speaking to or about monks, employ alternate verbs, names of body parts and pronouns. This results in what appears to foreigners as separate languages and, in fact, isolated villagers often are unsure how to speak with royals and royals raised completely within the court do not feel comfortable speaking the common register. As an example, the word for "to eat" used between intimates or in reference to animals is /siː/. Used in polite reference to commoners, it is /ɲam/. When used of those of higher social status, it is /pisa/ or /tɔtuəl tiən/. For monks the word is /cʰan/ and for royals, /saoj/.[8] Another result is that the pronominal system is complex and full of honorific variations, just a few of which are shown in the table below.[45]

| Situational usage | I/me | you | he/she/it | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intimate or addressing an inferior | អញ | [ʔaɲ] | ឯង | [ʔaɛ̯ŋ] | វា | [ʋiə̯] |

| neutral | ខ្ញុំ | [kʰɲom] | អ្នក | [neə̯̆ʔ] | គេ | [keː] |

| Formal | យើងខ្ញុំ or ខ្ញុំបាទ |

[jəːŋ kʰɲom] [kʰɲom baːt] |

លោក (or kinship term, title or rank) |

[loːk] | គាត់ | [kɔə̯t] |

| Layperson to/about Buddhist clergy | ខ្ញុំព្រះករុណា | [kʰɲom preə̯̆h kaʔruʔnaː] | ព្រះតេជព្រះគុណ | [preə̯̆h daɛ̯c preə̯̆h kun] | ព្រះអង្គ | [preə̯̆h ɑŋ] |

| Buddhist clergy to layperson | អាត្មា or អាចក្តី |

[aːttma] [aːckdəj] |

ញោមស្រី (to female) ញោមប្រុស (to male) |

[ɲoːm srəj] [ɲoːm proh] |

ឧបាសក (to male) ឧបាសិកា (to female) |

[ʔuʔbaːsaʔ] [ʔuʔbaːsiʔkaː] |

| when addressing royalty | ខ្ញុំព្រះបាទអម្ចាស់ or ទូលបង្គុំ (male), ខ្ញុំម្ចាស់ (female) | [kʰɲom preə̯̆h baːt aʔmcah] | ព្រះករុណា | [preə̯̆h kaʔruʔnaː] | ទ្រង់ | [truə̯̆ŋ] |

Writing system

Khmer is written with the Khmer script, an abugida developed from the Pallava script of India before the 7th century when the first known inscription appeared.[58] Written left-to-right with vowel signs that can be placed after, before, above or below the consonant they follow, the Khmer script is similar in appearance and usage to Thai and Lao, both of which were based on the Khmer system. The Khmer script is also distantly related to the Mon script, the ancestor of the modern Burmese script.[58] Within Cambodia, literacy in the Khmer alphabet is estimated at 77.6%.[59]

Consonant symbols in Khmer are divided into two groups, or series. The first series carries the inherent vowel /ɑː/ while the second series carries the inherent vowel /ɔː/. The Khmer names of the series, /aʔkʰosaʔ/ ('voiceless') and /kʰosaʔ/ ('voiced'), respectively, indicate that the second series consonants were used to represent the voiced phonemes of Old Khmer. As the voicing of stops was lost, however, the contrast shifted to the phonation of the attached vowels, which, in turn, evolved into a simple difference of vowel quality, often by diphthongization.[35] This process has resulted in the Khmer alphabet having two symbols for most consonant phonemes and each vowel symbol having two possible readings, depending on the series of the initial consonant:[22]

| ត + ា | = តា | /ta:/ | 'grandfather' |

| ទ + ា | = ទា | /tiə/ | 'duck' |

Examples

The following text is from Article 1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

| Khmer | មនុស្សទាំងអស់កើតមកមានសេរីភាពនិងភាពស្មើៗគ្នាក្នុងសិទ្ធិនិងសេចក្ដីថ្លៃថ្នូរ។ មនុស្សគ្រប់រូបសុទ្ធតែមានវិចារណញ្ញាណនិងសតិសម្បជញ្ញៈ ហើយត្រូវប្រព្រឹត្ដចំពោះគ្នាទៅវិញទៅមកក្នុងស្មារតីរាប់អានគ្នាជាបងប្អូន។ |

|---|---|

| Khmer transliteration |

mnoussa teangoasa kaetamk mean seripheap ning pheap smae knea knong setthi ning sechakdeithlaithnaur. mnoussa krobroub sotthote mean vichearonanhnhean ning satesambochonhnh haey trauv br pru td champoh knea towvinhtowmk knong smartei reaban knea chea bangobaaun. |

See also

- Literature of Cambodia

- Romanization of Khmer

References and notes

- Mikael Parkvall, "Världens 100 största språk 2007" (The World's 100 Largest Languages in 2007), in Nationalencyklopedin

- "Languages of ASEAN". Retrieved 7 August 2017.

- Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2017). "Khmeric". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2017). "Central Khmer". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- Laurie Bauer, 2007, The Linguistics Student’s Handbook, Edinburgh

- Oxford English Dictionary, "Khmer".

- "Enfield, N.J. (2005). Areal Linguistics and Mainland Southeast Asia" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-05-24. Retrieved 2011-10-28.

- David A. Smyth, Judith Margaret Jacob (1993). Cambodian Linguistics, Literature and History: Collected Articles. Routledge (UK). ISBN 978-0-7286-0218-2.

- Hul, Reaksmey; Woods, Ben (3 March 2015). "Campaign Aims to Boost Adult Literacy". The Cambodia Daily. Retrieved 7 February 2016.

- Diffloth, Gerard & Zide, Norman. Austroasiatic Languages Archived 2012-04-25 at the Wayback Machine.

- Thomas, David (1964). "A survey of Austroasiatic and Mon-Khmer comparative studies". The Mon-Khmer Studies Journal. 1: 149–163. Retrieved 19 June 2012.

- Sidwell, Paul (2009a). The Austroasiatic Central Riverine Hypothesis. Keynote address, SEALS, XIX.

- Diffloth, Gérard (2005). "The contribution of linguistic palaeontology and Austroasiatic". in Laurent Sagart, Roger Blench and Alicia Sanchez-Mazas, eds. The Peopling of East Asia: Putting Together Archaeology, Linguistics and Genetics. 77–80. London: Routledge Curzon.

- Shorto, Harry L. edited by Sidwell, Paul, Cooper, Doug and Bauer, Christian (2006). A Mon–Khmer comparative dictionary. Canberra: Australian National University. Pacific Linguistics. ISBN 0-85883-570-3

- Central Khmer at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015)

- Northern Khmer at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015)

- Sidwell, Paul (2006). "Khmer/Cambodian". Mon-Khmer.com. Australian National University. Archived from the original (lecture) on 2011. Retrieved 6 February 2016.

- Nancy Joan Smith-Hefner (1999). Khmer American: Identity and Moral Education in a Diasporic Community. University of California. ISBN 978-0-520-21349-4.

- Wayland, Ratree; Jongman, Allard (2003). "Acoustic correlates of breathy and clear vowels: the case of Khmer" (PDF). Journal of Phonetics. 31 (2): 181–201. doi:10.1016/s0095-4470(02)00086-4. Retrieved 6 February 2016.

- Sidwell, Paul (2009). Classifying the Austroasiatic languages: history and state of the art. LINCOM studies in Asian linguistics, 76. Munich: Lincom Europa.

- Ferlus, Michel (1992). "Essai de phonétique historique du khmer (Du milieau du primier millénaire de notre ère à l'époque actuelle)". Mon–Khmer Studies. 2 (6): 7–28.

- Huffman, Franklin. 1970. Cambodian System of Writing and Beginning Reader. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-01314-0

- Olivier, Bernon de (1988). Cholticha, Bamroongraks; Wilaiwan, Khanittanan; Laddawan, Permch (eds.). "Khmer of Surin: Lexical Remarks" (PDF). The International Symposium on Language and Linguistics. Bangkok, Thailand: Thammasat University: 258–262. Retrieved 6 February 2016.

- Thomas, David (1990). "On the 'language' status of Northern Khmer". JLC. 9 (1): 98–106.

- Phonetic variation of final trill and final palatals in Khmer dialects of Thailand Suwilai, Premsrirat; Mahidol University; Mon-Khmer Studies 24:1–26; pg 1

- William Allen A. Smalley (1994). Linguistic Diversity and National Unity: Language Ecology in Thailand. University of Chicago. ISBN 978-0-226-76288-3.

- Unrepresented Peoples and Nations Organization Khmer Krom Profile Retrieved 19 June 2012

- Thach, Ngoc Minh. Monosyllablization in Kiengiang Khmer. University of Ho Chi Minh City.

- Try, Tuon; Chambers, Marcus (2006). "Situation Analysis" (PDF). Stung Treng Province Cambodia, IUCN, MRC, UNDP: 45–46. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2017). "Old Khmer". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- Sak-Humphry, Channy. The Syntax of Nouns and Noun Phrases in Dated Pre-Angkorian Inscriptions. Mon Khmer Studies 22: 1–26.

- Harris, Ian (2008). Cambodian Buddhism: History and Practice. Hawaii: University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-3298-8.

- Chandler, David P. (1992). A history of Cambodia (2, illustrated ed.). Westview Press. ISBN 978-0813309262.

- Sasagawa, Hideo (2015). "The Establishment of the National Language in Twentieth-Century Cambodia: Debates on Orthography and Coinage" (PDF). Southeast Asian Studies. 4 (1). Retrieved 6 February 2016.

- Minegishi, M (2006). "Khmer". In Keith Brown (ed.). Encyclopedia of Language and Linguistics (2 ed.). Elsevier. pp. 4981–4984.

- Jacob, JM (2002). "The Structure of the Word in Old Khmer". In VI Braginskiĭ (ed.). Classical Civilizations of South-East Asia: Key Papers from SOAS. Routledge.

- International Encyclopedia of Linguistics, OUP 2003, p. 356.

- Minegishi, Makoto (1986). "On Takeo Dialects of Khmer: Phonology and World List" (PDF). Retrieved 2008-12-04.

- Wayland, Ratree. "An Acoustic Study of Battambang Khmer Vowels." The Mon-Khmer Studies Journal. 28. (1998): 43–62.

- Jacob, Judith M (1976). "An Examination of the Vowels and final Consonants in Correspondences between pre-Angkor and modern Khmer" (PDF). Pacific Linguistics. 42 (19): 27–34. Retrieved 27 January 2016.

- Phonetic and Phonological Analysis of Khmer

- Huffman, Franklin (1970). Modern Spoken Cambodian (1998 ed.). Ithaca, NY: Cornell Southeast Asia Program Publications. ISBN 978-0877275213.

- Nacaskul, Karnchana (1978). "The syllabic and morphological structure of Cambodian words" (PDF). Mon-Khmer Studies Journal. 7: 187. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 October 2017. Retrieved 24 January 2016.

- Schiller, Eric (1994). "Khmer Nominalizing and Causitivizing Infixes" (PDF). University of Chicago. Retrieved 2008-12-04.

- Headley, Robert K.; Chhor, Kylin; Lim, Lam Kheng; Kheang, Lim Hak; Chun, Chen. 1977. Cambodian-English Dictionary. Bureau of Special Research in Modern Languages. The Catholic University of America Press. Washington, D.C. ISBN 0-8132-0509-3

- Jacob, Judith M (1991). "A Diachronic Survey of some Khmer particles (7th to 17th centuries)" (PDF). Essays in Honour of HL Shorto. 1991: 193. Retrieved 24 January 2016.

- Huffman, Franklin. 1967. An outline of Cambodian Grammar. PhD thesis, Cornell University.

- Haiman, John (2011). Cambodian: Khmer (London Oriental and African Language Library, Book 16). John Benjamins Publishing Company. ISBN 978-9027238160. Retrieved 27 January 2016.

- Jacob, Judith (1968). Introduction to Cambodian (School of Oriental and African Studies). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0197135563.

- David Smyth (1995). Colloquial Cambodian: A Complete Language Course. Routledge (UK). ISBN 978-0-415-10006-9.

- Karnchana, Nacaskul (1978). "The syllabic and morphological structure of Cambodian words" (PDF). Mon-Khmer Studies Journal. 3: 183–200. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 October 2017. Retrieved 6 February 2016.

- Huffman, F. E., Promchan, C., & Lambert, C.-R. T. (1970). Modern spoken Cambodian. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-01315-9

- East and Southeast Asian Languages: A First Look Archived 2012-11-20 at the Wayback Machine at Oxford University Press Online

- Moravcsik, Edith M. (1993). "Why is Syntax Complicated". In Mushira, Eid; Iverson, Gregory (eds.). Principles and Prediction: The analysis of natural language. Papers in honor of Gerald Sanders (Volume 98 of Current Issues in Linguistic Theory). John Benjamins Publishing. pp. 73–74. ISBN 978-9027276971.

- Ehrman, Madeline Elizabeth; Kem, Sos; Lim, Hak Kheang (1974). Contemporary Cambodian: Grammatical Sketch. Foreign Service Institute, US Department of State.

- Mori, K. (2007). Soichi, I. (ed.). "Khmer final particles phɔɔŋ & dae" (PDF). SEALS XIII Papers from the 13th Annual Meeting of the Southeast Asian Linguistics Society 2003. Canberra, ACT: Pacific Linguistics, Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies, The Australian National University: 139–149–6. Retrieved 6 February 2016.

- Jacob, Judith M (1965). "Notes on the numerals and numeral coefficients on Old, Middle, and Modern Khmer". Lingua. 15: 144. doi:10.1016/0024-3841(65)90011-2.

- "Khmer Alphabet at Omniglot.com". Archived from the original on 2012-02-13. Retrieved 2007-02-13.

- "United Nations in Cambodia "Celebration of International Literacy Day, 2011"". Archived from the original on 2011-10-27. Retrieved 2012-02-20.

Further reading

- Ferlus, Michel. (1992). Essai de phonétique historique du khmer (Du milieu du premier millénaire de notre ère à l'époque actuelle)", Mon–Khmer Studies XXI: 57–89)

- Headley, Robert and others. (1977). Cambodian-English Dictionary. Washington, Catholic University Press. ISBN 0-8132-0509-3

- Herington, Jennifer and Amy Ryan. (2013). Sociolinguistic Survey of the Khmer Khe in Cambodia. Chiang Mai: Linguistics Institute, Payap University.

- Huffman, F. E., Promchan, C., & Lambert, C.-R. T. (1970). Modern spoken Cambodian. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-01315-9

- Huffman, F. E., Lambert, C.-R. T., & Im Proum. (1970). Cambodian system of writing and beginning reader with drills and glossary. Yale linguistic series. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-01199-7

- Jacob, Judith. (1966). ‘Some features of Khmer versification’, in C. E. Bazell, J. C. Catford, M. A. K. Halliday, and R. H. Robins, eds., In Memory of J. R Firth, 227–41. London: Longman. [Includes discussion of the two series of syllables and their places in Khmer shymes]

- Jacob, Judith. (1974). A Concise Cambodian-English Dictionary. London, Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-713574-9

- Jacob, J. M. (1996). The traditional literature of Cambodia: a preliminary guide. London oriental series, v. 40. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-713612-5

- Jacob, J. M., & Smyth, D. (1993). Cambodian linguistics, literature and history: collected articles. London: School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London. ISBN 0-7286-0218-0

- Keesee, A. P. K. (1996). An English-spoken Khmer dictionary: with romanized writing system, usage, and indioms, and notes on Khmer speech and grammar. London: Kegan Paul International. ISBN 0-7103-0514-1

- Meechan, M. (1992). Register in Khmer the laryngeal specification of pharyngeal expansion. Ottawa: National Library of Canada = Bibliothèque nationale du Canada. ISBN 0-315-75016-2

- Sak-Humphry, C. (2002). Communicating in Khmer: an interactive intermediate level Khmer course. Manoa, Hawai'i: Center for Southeast Asian Studies, School of Hawaiian, Asian and Pacific Studies, University of Hawai'i at Manoa. OCLC: 56840636

- Smyth, D. (1995). Colloquial Cambodian: a complete language course. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-10006-2

- Stewart, F., & May, S. (2004). In the shadow of Angkor: contemporary writing from Cambodia. Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press. ISBN 0-8248-2849-6

- Tonkin, D. (1991). The Cambodian alphabet: how to write the Khmer language. Bangkok: Trasvin Publications. ISBN 974-88670-2-1

External links

| Khmer edition of Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Khmer language. |

- Khmer phrasebook from Wikivoyage

- Kheng.info—An online audio dictionary for learning Khmer, with thousands of native speaker recordings and text segmentation software.

- SEAlang Project: Mon–Khmer languages. The Khmeric Branch

- Khmer Swadesh vocabulary list (from Wiktionary's Swadesh-list appendix)

- Dictionary and SpellChecker open sourced and collaborative project based on Chuon Nath Khmer Dictionary

- How to install Khmer script on a Windows 7 computer

- How to install Khmer script on a Windows XP computer

- Khmer at UCLA Language Materials project

- Online Khmer & English dictionary

- Khmer Online Dictionaries

- Khmer audio lessons at Wikiotics

- http://unicode-table.com/en/sections/khmer/

- http://unicode-table.com/en/sections/khmer-symbols/