Kingdom of Singapura

The Kingdom of Singapura (Malay: Kerajaan Singapura) was a historical Malay kingdom thought to have been established upon the main island of Singapore (then known as Pulau Ujong or Temasek), from 1299 to 1398. Conventional view marks c. 1299 as the founding year of the kingdom by Sang Nila Utama (also known as "Sri Tri Buana"), whose father is Sang Sapurba, who according to legend is the common great ancestor of most of the Malay monarchies in the Malay World. The historicity of this kingdom, based on the account given in the Malay Annals, is the subject of academic debates, and many historians consider only its last ruler Parameswara (or Sri Iskandar Shah) a historically attested figure.[2] Archaeological evidence from Fort Canning Hill and the nearby banks of the Singapore River has nevertheless demonstrated the existence of a thriving settlement and a trade port in the 14th century.[3]

| 1299–1398 | |||||||||||||||

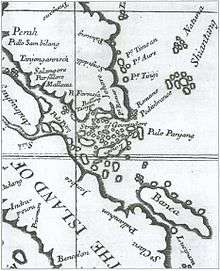

.jpg) Kingdom of Singapore, with ruins of an old wall still visible in 1825 and marked on this map. | |||||||||||||||

| Capital | Singapura[1] | ||||||||||||||

| Common languages | Old Malay | ||||||||||||||

| Religion | Syncretic forms of Hinduism and Buddhism | ||||||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||||||

| King | |||||||||||||||

• 1299–1347 | Sang Nila Utama (Sri Tri Buana) | ||||||||||||||

• 1347–1362 | Sri Wikrama Wira | ||||||||||||||

• 1362–1375 | Sri Rana Wikrama | ||||||||||||||

• 1375–1389 | Sri Maharaja | ||||||||||||||

• 1389–1398 | Parameswara (Iskandar Shah) | ||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||

• Founding of Temasek by Sang Nila Utama | 1299 | ||||||||||||||

• Siege by Siamese forces | 1330 | ||||||||||||||

• Siege by Majapahit under Hayam Wuruk | 1350 | ||||||||||||||

• Majapahit invasion and escape of Parameswara (Iskandar Shah) to the Malay Peninsula, leading to the establishment of its successor state, the Malacca Sultanate | 1398 | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||||||||

Part of a series on the |

||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| History of Singapore | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Early history (pre-1819)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

British colonial era (1819–1942)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Japanese Occupation (1942–1945)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Post-war period (1945–1962)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Internal self-government (1955–1963)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Merger with Malaysia (1963–1965) |

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Republic of Singapore (1965–present)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

The settlement developed in the 13th or 14th century and rose from a small Srivijayan trading outpost into a centre of international trade in the Malay Archipelago, India and the Yuan Dynasty. It was however claimed by two regional powers at that time, Ayuthaya from the north and Majapahit from the south. As a result, the kingdom's fortified capital was attacked by at least two major foreign invasions before it was finally sacked by the Majapahit in 1398 according to the Malay Annals, or the Siamese according to Portuguese sources.[4][5][6] The last king, Parameswara or Iskandar Shah, fled to the west coast of the Malay Peninsula to establish the Malacca Sultanate in 1400.

Etymology

The name Singapura is derived from Sanskrit meaning "Lion City".[7] Singa comes from the Sanskrit word siṃha, which means "lion", and pūra means "city" in Sanskrit.[8] According to the Malay Annals, Sri Tri Buana and his men were exploring Tanjong Bemban while in Bintan when he spotted an island with white sandy beach from a high point. On learning that the island was called Temasek, they set sail for the island, but encountered a severe storm on the way. After they managed to land safely on the island, they went to hunt for wild animals. He suddenly saw a strange animal with a red body, black head and a white neck breast. It was a fine-looking animal and moved with great speed as it disappeared into the jungle. He asked his chief minister, Demang Lebar Daun, what animal it was, and was told that it probably was an Asiatic lion. He then decided to stay in Temasek, named the city he founded Singapura or "Lion City".[9][10]

Some scholars believe that the person Sri Tri Buana and the story of its founding to be fictional, and a number of alternative suggestions for the origin of the name of Singapore have been given. For example, it has been proposed that the name Singapura was adopted by Parameswara as an indication that he was re-establishing in Temasek the lion throne that he had originally set up in Palembang as a challenge to the Javanese Majapahit Empire.[11] In this version of events, Parameswara had assassinated the local ruler of Temasek and usurped the throne, and changed the name of Temasek to strengthen the legitimacy of his claim over the island.[7] Others linked the name to the Javanese kingdom of Singhasari as well as a Majapahit Buddhist sect whose adherents were referred to as lions. Although it is believed that the name Singapura replaced Temasek some time in the 14th century, the origin of the name cannot be determined with certainty.[11]

Historiography

The only comprehensive account of Singapore's history in this era is the Malay Annals. These were written and compiled during the heyday of Melaka and re-compiled in 1612 by the court of its successors in the Johor Sultanate. It is the basis for accounts of its founding, the succession of rulers and its decline. As no specific date is given in the Malay Annals, the chronology of the history of the kingdom of Singapura as set out in the Malay Annals was calculated from the date of death of Parameswara given in the Ming Annals.[1] While various aspects of the accounts of the Melaka and Johor sultanates given in the Malay Annals are relatively accurate, the same could not be said for the kingdom of Singapura for which there is little corroborating evidence for large part of its accounts. Historians are therefore generally in doubt over the historicity of the kingdom as described in the semi-historical Malay Annals,[2][12] nevertheless some consider Singapura to be a significant polity that existed between the decline of Srivijaya and the rise of Melaka.[13][14] Some also argued that the author of the Malay Annals, whose purpose is to legitimise the claim of descent from the Srivijayan ruling house, invented the five kings of Singapura to gloss over an inglorious period of its history.[11] However, Iskandar Shah/Parameswara, the last ruler of Singapura and founder of the Melaka Sultanate, is a figure that could be considered factual.[11]

Accounts of Singapura in its final years are also briefly given in Portuguese sources, such as those by Tomé Pires, Brás de Albuquerque (who published letters by his father Afonso de Albuquerque), Godinho de Erédia, and João de Barros.[15] For example, the Suma Oriental, written shortly after the Portuguese conquest of Melaka, briefly mentions Singapura in relation to the foundation of Melaka. Both Suma Oriental and Malay Annals contain similar stories about a fleeing Srivijayan prince who arrived and lay claim to Singapura, and about the last king of Singapura who fled to the west coast of Malay peninsula to found Melaka. However, both accounts differ markedly as Suma Oriental identifies the fleeing prince and the last king of Singapura as Parameswara. In contrast, the Malay Annals identifies the fleeing prince and the last king as completely two different persons separated by five generations, Sang Nila Utama and Iskandar Shah respectively. Suma Oriental noted further that the fleeing Srivijayan prince assassinated the local ruler "Temagi" or "Sang Aji" and usurped the throne of Singapura sometimes around the 1390s, and Parameswara then ruled Singapura for five years with the help of the Çelates or Orang Laut.[16]

Portuguese sources also named Iskandar Shah as Parameswara's son, Chinese Ming dynasty sources similar named Iskandar Shah as the second ruler of Melaka. Many modern scholars believe Parameswara to be the same person as Iskandar Shah, and some scholars argued that they were mistaken as two different persons due to a change of name from Parameswara to Iskandar Shah after he had converted to Islam.[17][18] There are however also different opinions, and many now accept Megat Iskandar Shah as the son of Parameswara.[19]

The only first-hand account of 14th-century Singapore may be the descriptions of a place named Danmaxi (generally identified with Temasek) written by Wang Dayuan in the Daoyi Zhilue, a record of his travels. It indicates that Temasek was ruled by a local chief during Wang's visit around 1330,[20] however the word used (酋長, "tribal chief") by Wang indicates that the ruler may not have been independent, rather he was a vassal of another more powerful state.[21] Wang also mentioned that the Siamese attacked the fortified city of Temasek with around 70 ships a few years before he visited, but Temasek successfully resisted the attack which lasted a month.[16] Other settlements on the island recorded by Wang are Long Ya Men (identified with Keppel Harbour) and Ban Zu (possibly a transcription of Pancur, or a sacred spring on Fort Canning Hill); the exact relationship between these settlements is unclear.

Archaeological evidence

Although the existence of the kingdom as described in the Malay Annals is debatable, archaeological excavations on Fort Canning and its vicinity along the banks of the Singapore River since 1984 by John Miksic have confirmed the presence of a thriving settlement and a trade port here during the 14th century.[22] Remnants of a wall of significant size (described by John Crawfurd as around five metres wide and three metres high) and unique to the region were found inland along present day Stamford Road. Excavations also found evidence of structures built on what is now Fort Canning Hill, along with evidence of fruit orchards and terraces. Local lore when the British arrived in the early 1800s associated it with the royalty of ancient Singapura where its last ruler was buried, and the hill was known to them as the forbidden hill (Bukit Larangan), as it was the site of spirits. Items of gold jewelries of Javanese Majapahit style, including rings, earrings, an arm band and what was likely a head ornament have also been found in 1928 when workers excavated the hill for a reservoir.[23] Numerous fragments of ceramics, porcelain, and other objects have been found at three different locations around the Singapore River and Fort Canning Hill, with those from Fort Canning Hill of a higher quality than the others, offering further evidence that it was the residence of the elites, all of which supports the notion that Singapore was a political and commercial center in the 14th century.[3]

History

The once great empire of Srivijaya had been weakened by numerous raids launched by the Chola Empire in the 11th century and was entering its terminal decline by the end of the 13th century, when it caught the attention of the expansionist Javanese King, Kertanegara of Singhasari. In 1275, Kertanegara launched the Pamalayu expedition to overrun Sumatra and by 1288, Singhasari naval expeditionary forces successfully sacked Jambi and Palembang and brought Srivijaya to its knees. Over the course of the next decade, the Majapahit Empire would emerge as the regional hegemon in the wake of the Mongol invasion of Java.

The conquest of Srivijaya caused a massive flight of the Srivijayan princes and nobles, some of whom raised rebellions against the Javanese rule and left the area of southern Sumatra in chaos and desolation. With this period of political fragmentation as a backdrop, Temasek, also known as Singapura, emerged as a regional emporium around the turn of the 14th century, with the archaeology of Singapore indicating a strong entanglement with mainland and archipelagic Southeast Asia as well as with Yuan Dynasty and Ming Dynasty China.

The primary source concerning the history of the rulers of Singapura is Malay Annals, and the rest of this section is mainly built upon reconstructions from its text, although corroborating evidence is scarce and its polemic nature suggests strongly against literal interpretations of this chronicle.[25] Other sources for Singapore's history in this period include the Yuan Dynasty merchant Wang Dayuan's compendium known as the Daoyi Zhilue ("Records of the Barbarians of the Isles"), Portuguese apothecary Tome Pires' Suma Oriental and scattered references in the Majapahit Nagarakretagama and Ming records.[26]

Sang Nila Utama

.jpg)

According to the Malay Annals, a fleeing Srivijayan prince named Sang Nila Utama, who claimed to be a descendant of Alexander the Great (via his Islamic interpretation as Iskandar Zulkarnain), took refuge in the island of Bintan for several years before he set sail and landed on Temasek in 1299.[27] In the Srivijayan era, Temasek was a small trading outpost and primarily inhabited by Orang Laut seafarers. Historically, these Orang Laut were very loyal to the Malay kings, patrolling adjacent seas and repelling other petty pirates, directing traders to their Malay overlords' ports and maintaining those ports' dominance in the area.[28] These Orang Laut eventually acclaimed him as Raja ("king"), and Sang Nila Utama renamed Temasek as "Singapura" and founded his capital around the mouth of the Singapore River.

The area was suitable for a new settlement due to the nearby presence of a spring and a hill. The fresh water from a spring on the hill's slope served both as a bathing place for royalty and, at the base of a hill, a source of fresh water for the populace. The hill (modern-day Fort Canning hill) itself represented Mount Meru, the seat of the gods in Hindu-Buddhist mythology, which was associated with kingship and divinity in ancient Southeast Asian culture. Building a palace on a hill would have helped Sang Nila Utama to assert his role as a semi-divine ruler.[29]

The king styled himself as Sri Tri Buana, or "The Lord of Three Worlds", indicating authority over the universe.[30] Within few decades, the small settlement grew into a thriving cosmopolitan city serving as a port of call for richly laden trade ships plying the pirate-infested waters of the Melaka Straits region. The Malay Annals mention that supplies of workers, horses and elephants were sent from Bintan by the king's adoptive mother, Queen Parameswari of Bintan.

It was during this period that contacts with Yuan Dynasty China were established. It was recorded that in 1320, Yuan China sent envoys to Long Ya Men (thought by some to stretch from modern-day Keppel Harbour south to northwestern side of Sentosa and west to what is today Labrador Park) "to obtain tame elephants", and the natives of Long Ya Men returned with tributes and a trade mission to China in 1325.[31]

Long Ya Men was part of Temasek (the kingdom of Singapura) according to Chinese traveler Wang Dayuan who visited Temasek in the 1330s and wrote an account of his travel in Dao Yi Zhi Lue. He describes Temasek as comprising two settlements – "Ban Zu" (after the Malay word "pancur" or fresh-water spring), a peaceful trading port city under the rule of the King. The second settlement he describes as an area surrounding the "Long-ya-men", which was occupied by ferocious pirates who launched frequent attacks on passing merchant ships. He also notes that Chinese traders lived there, "side by side with the natives". He also mentions some of the trade goods bartered in Singapura: red gold, cotton prints, blue satin, lakawood and fine hornbill casques.[32][33]

The Siamese attempted to subjugate the island kingdom in this period. According to Wang's account, possibly a few years before he visited Temasek in the 1330s, a Siamese fleet consisted of 70 junks descended upon the island kingdom and launched an attack. The moated and heavily fortified city managed to withstand the siege of the Siamese for a month until the Siamese fleet withdrew with the arrival of Javanese ships.[5][16]

Sri Wikrama Wira

.jpg)

In 1347, Sri Teri Buana was succeeded by Sri Wikrama Wira. The increasingly powerful Javanese kingdom of Majapahit, the successor of Singhasari, began eyeing the growing influence of the tiny island kingdom. Under the leadership of its ambitious warlord, Gajah Mada, Majapahit started to embark on overseas expansions against all kingdoms of Nusantara including the remnants of the Srivijaya. In 1350, Hayam Wuruk ascended to the throne of Majapahit. The new king sent an envoy to Singapura demanding the submission of the tiny kingdom. Wikrama Wira refused to do so and even sent a symbolic message threatening to shave the Majapahit king's head should he proceed to Singapura.[34]

The furious Majapahit king ordered an invasion with a fleet of 100 main warships (jong) and innumerable smaller vessels under the command of Damang Wiraja.[35][36] The fleet passed through the island of Bintan, from where the news spread to Singapura. The defenders immediately assembled 400 warships to face the invasion. Both sides clashed on the coast of Singapura in a battle that took place in three days. Many were slain on both sides, however in the evening of the third day, the Javanese were driven back to their ships.[37][38]

Sri Rana Wikrama

The victorious Sri Wikrama Wira died in 1362 and succeeded by his son, Sri Rana Wikrama. Despite the failure in the previous campaign, the Javanese chronicle Nagarakretagama lists Singapura as a subject of Majapahit in 1365. During his reign, Sri Rana Wikrama established a diplomatic ties with a Sumatran Muslim kingdom, Peureulak.[4] It was during the reign of Sri Rana Wikrama that a legendary man with an unusual strength, Badang, was said to have demonstrated his feat of strength in Rana Wikrama's court, including casting the Singapore Stone to its location at the mouth of the Singapore River, where it stood until it was demolished by the British East India Company.[39]

Sri Maharaja

In 1375, Rana Wikrama was succeeded by his son Sri Maharaja. According to Malay Annals, the reign of Sri Maharaja was marked with the event of todak (garfish) ravaging the coast of Singapura. A young boy, Hang Nadim, thought of an ingenious solution to fend off the todak by planting banana plants along the shoreline, where they would get stuck whilst leaping out of the water. The king was initially grateful, but felt increasingly envious of the attention the boy's intelligence was garnering, and ordered to have the boy executed.[40]

Parameswara/Iskandar Shah

In 1387, Paduka Sri Maharaja was succeeded by Iskandar Shah, commonly identified as the king Parameswara mentioned in the Suma Oriental of Tome Pires. Based on his peculiar Persian name and title, it is believed that Iskandar Shah was the first king of Singapura to embrace Islam. Portuguese accounts by Pires however suggested that the Iskandar Shah mentioned in his text (and said to be Parameswara's son) only converted when he was 72 as the ruler of Malacca.[17]

Fall of Singapura and Establishment of Malacca

As mentioned in the Malay annals, the story of the fall of Singapura and the flight of its last king begins with Iskandar Shah's accusation of one of his concubines of adultery. As punishment, the king had her stripped naked in public. In revenge, the concubine's father, Sang Rajuna Tapa who was also an official in Iskandar Shah's court, secretly sent a message to the king of Majapahit, pledging his support should the king choose to invade Singapura. In 1398, Majapahit dispatched a fleet of 300 jong and hundreds of smaller vessels (of kelulus, pelang, and jongkong types), carrying no fewer than 200,000 men.[41]

The Javanese soldiers engaged with the defenders in a battle outside the fortress, before forcing them to retreat behind the walls. The invasion force laid a siege of the city and repeatedly tried to attack the fortress. However the fortress proved to be impregnable.[4][5][42] After about a month passed, the food in the fortress began to run low and the defenders were on the verge of starvation. Sang Rajuna Tapa was then asked to distribute whatever grain left to the people from the royal store. Seeing this opportunity for revenge, the minister lied to the King, saying the stores were empty. The grain was not distributed and the people eventually starved. The final assault came when the gates were finally opened under the order of the treacherous minister. Knowing that defeat was imminent, Iskandar Shah and his followers fled the island. The Majapahit soldiers rushed into the fortress and a terrible massacre ensued.[42] According to the Malay Annals, "blood flowed like a river" and the red stains on the laterite soil of Singapore are said to be blood from that massacre.[43]

Portuguese sources give a significantly different account of the life of last ruler of Singapura. These accounts named the last ruler of Singapure and founder of Malacca as Parameswara, a name also found in Ming annals. It is generally believed that the Iskandar Shah of the Malay Annals is the same person as Parameswara.[11] However, Portuguese accounts and Ming sources indicate that Iskandar Shah was the son of Parameswara who became the second ruler of Malacca,[15] and some therefore argued for Megat Iskandar Shah as the son of Parameswara.[19] According to the Portuguese accounts, Parameswara was a prince from Palembang who attempted to challenge Javanese rule over Palembang sometime after 1360. The Javanese then attacked and drove Parameswara out of Palembang. Parameswara escaped to Singapore, and was welcomed by its ruler of with the title Sang Aji named Sangesinga. Parameswara assassinated the local ruler after 8 days, then ruled Singapura for five years with the help of the Çelates or Orang Laut.[16] He was however driven out by the Thais, possibly as a punishment for killing the Sang Aji whose wife may have been from the Kingdom of Patani.[44]

Administration

Malay Annals provides a well-defined hierarchical structure of Singapura, which was later partly adopted by its successor, Melaka. The highest hierarchical position was the Raja (king) as an absolute monarch. Next to the king were Orang Besar Berempat (four senior nobles) headed by a Bendahara (equivalent to a Grand Vizier) as the highest-ranking officer and the advisor to the King. He was then assisted by three other senior nobles based on the order of precedence namely; Perdana Menteri (prime minister), Penghulu Bendahari (chief of treasurer) and Hulubalang Besar (grand commander).

The Perdana Menteri assisted Bendahara in administrating the internal affairs of the kingdom and usually sit opposite to Bendahara in the royal court, while Penghulu Bendahari was responsible to the financial affairs of the kingdom.

The Hulubalang Besar acted as a chief of staff of the army and commanded several other Hulubalangs (commanders), that in turn leading smaller military units. These four senior nobles were then assisted by other lower ranking officials titled Orang Besar Caterias, Sida Bentaras and Orang Kayas.[45]

Trade

Singapura's rise as a trade-post was concurrent with the era known as Pax Mongolica or "Mongolian peace", where the Mongol influence over both the overland and maritime silk roads provided a context in which a new global trading system could develop. Previously, shipping occurred on a long-distance routes from the far east to India or even further west to the Arabian peninsula, which was relatively costly, risky and time-consuming. However, the new trading system involved the division of the maritime silk road into three segments: an Indian Ocean sector linking the Gulf of Aden and the Straits of Hormuz-based Arab traders to India, a Bay of Bengal sector linking the Indian ports with the Straits of Malacca and its associated ports including Singapura and the South China Sea sector linking Southeast Asia with Southern China.[46]

Singapura achieved its significance due to its role as a port. It seems to fit as least in part the definition of a port of trade in which trade is less a function of the economy and more a function of government policy; thus trading would have been highly structured and institutionalized, with government agents playing key roles in port activities. Portuguese traders' account in particular, suggest that Singapura operated in such a manner. Reports from merchants of different countries also indicate that Singapura was a point of exchange, rather than a source for goods. Local products were limited in type and mainly consisted of lakawood, tin, hornbill casques (an ivory-like part of the hornbill bird, which was valued for carved ornaments), some wooden items and cotton. Other commonly traded products included a variety of fabrics (cotton and satins), iron rods, iron pots, and porcelains. Chinese traders also reported that there were agricultural products but very few due to poor soil. Although these goods were also available from other Southeast Asian ports, those from Singapura were unique in terms of their quality. Singapura also acted as a gateway into the regional and international economic system for its immediate region. South Johor and the Riau Archipelago supplied products to Singapore for export elsewhere, while Singapura was the main source of foreign products to the region. Archaeological artefacts such as ceramics and glassware found in the Riau Archipelago evidence this. In addition, cotton was transshipped from Java or India through Singapura.[47]

The increase in activities by Chinese traders seems especially significant for Singapura and its trade. Report by Wang Dayuan indicates that, by this time, there was a Chinese settlement in Singapore living peaceably with the indigenous population.[48]

Legacy

— Sir Stamford Raffles, the founder of the British colony of Singapore, on his desire to be buried upon Fort Canning Hill were he to pass away in Singapore[49]

According to the Malay Annals, after they had sacked Singapura, the Majapahit army abandoned the city and returned to Java. The city would have been ruined and greatly depopulated. The rivalry between the courts of Javanese and Malay in the region nevertheless was renewed few years later when the last king Iskandar Shah, founded his new stronghold on the mouth of Bertam river in the west coast of Malay peninsula. Within decades, the new city grew rapidly to become the capital of Melaka Sultanate and emerged as the primary base in continuing the historic struggles of Singapura and Srivijaya, against their Java-based nemeses. The account by João de Barros suggests that Singapura did not end suddenly after the attack by the Siamese, rather Singapore declined gradually when Parameswara's son Iskandar Shah pushed for trade to move to Melaka instead of Singapura.[50]

As a major entrepot, Melaka attracted Muslim traders from various part of the world and became a centre of Islam, dissemanting the religion throughout the Maritime Southeast Asia. The expansion of Islam into the interiors of Java in 15th century led to the gradual decline of Hindu-Majapahit before it finally succumbed to the emerging local Muslim forces in the early 16th century. The period spanning from Melakan era right until the age of European colonisation, saw the domination of Malay-Muslim sultanates in trade and politics that eventually contributed to the Malayisation of the region.[51]

By the mid-15th century, Majapahit found itself unable to control the rising power of Melaka that began to gain effective control of Melaka straits and expands its influence to Sumatra. Singapura was also absorbed into its realm and once served as the fiefdom of Melakan Laksamana (or admiral).[52] The Johor Sultanate emerged as the dominant power around the Straits of Singapore until it was assimilated into the sphere of influence of the Dutch East India Company; the island of Singapore would not regain autonomy from Johor until Sir Stamford Raffles claimed it and its port for the British East India Company in 1819, deliberately invoking its history as related in the Malay Annals,[53] whose translation by Dr. John Leyden he published posthumously in 1821.[54] The dispute concerning Singapore's legal status, along with other matters arising from British seizure of Dutch colonial possessions during the Napoleonic Wars, was settled by the Anglo-Dutch Treaty of 1824, permanently dividing archipelagic and mainland Southeast Asia.

The independent Republic of Singapore, following the confirmation of its past as the Kingdom of Singapura through its archaeology, has promoted Singapura's history as a regional emporium, showcasing it in the Maritime Experiential Museum on Sentosa[55] and incorporating the chronicle of Sang Nila Utama into its primary school social sciences curriculum.[56] As part of events commemorating the bicentennial of Raffles' claim to Singapore, a statue of Sang Nila Utama has been erected (along with those of other Singaporean pioneers contemporary with Raffles) at the Raffles' Landing Site along the very same Singapore River which the Kingdom of Singapura was built upon.[57]

References

- 1. Linehan, W. (1947, December). The kings of 14th century Singapore. Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, 20(2)(142), 117, 120. Retrieved from JSTOR; The kings of Singapore. (1948, February 26). The Straits Times, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG

- Miksic 2013, p. 154

- Abshire 2011, p. 19&20

- Tsang & Perera 2011, p. 120

- Sabrizain

- Abshire 2011, p. 19&24

- "Temasek/Singapora". HistorySG.

- Ernst Eichler (ed.). Namenforschung / Name Studies / Les noms propres. 1. Halbband. Walter de Gruyter. p. 905. ISBN 9783110203424.

- Miksic 2013, p. 150

- Dr John Leyden and Sir Thomas Stamford Rffles (1821). Malay Annals. Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, and Brown. pp. 40–44.

- C.M. Turnbull (30 October 2009). A History of Modern Singapore, 1819-2005. NUS Press. pp. 21–22. ISBN 978-9971694302.

- Abshire 2011, pp. 19&20

- Paul Wheatley (1964). Impressions of the Malay Peninsula in Ancient Times. Eastern Universities Press. pp. 101–118.

- Chong Guan Kwa, Derek Thiam Soon Heng, Tai Yong Tan (2009). Singapore, a 700-year History: From Early Emporium to World City. National Archives of Singapore. ISBN 9789810830502.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Miksic 2013, p. 162

- Miksic 2013, p. 356

- Miksic 2013, p. 219

- Cheryl-Ann Low. "Iskandar Shah". Singapore Infopedia. National Library Board.

- Wang, G. (2005). "The first three rulers of Malacca". In L., Suryadinata (ed.). Admiral Zheng He and Southeast Asia. International Zheng He Society / Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. pp. 26–41. ISBN 9812303294.

- Paul Wheatley (1961). The Golden Khersonese: Studies in the Historical Geography of the Malay Peninsula before A.D. 1500. Kuala Lumpur: University of Malaya Press. pp. 82–83. OCLC 504030596.

- Miksic 2013, pp. 177–178

- Miksic, John N (2000). "Recent Archaeological Excavations in Singapore: A Comparison of Three Fourteenth-Century Sites" (PDF). Bulletin of the Indo-Pacific Prehistory Association. 20: 56–61. ISSN 0156-1316. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 August 2007. Retrieved 28 March 2017.

- "Javanese-style gold jewellery discovered at Bukit Larangan (Fort Canning Hill)". Roots. National Heritage Board.

- Kulke, Hermann (2004). A history of India. Rothermund, Dietmar, 1933– (4th ed.). New York: Routledge. ISBN 0203391268. OCLC 57054139.

- John N. Miksic (15 November 2013). Singapore and the Silk Road of the Sea, 1300-1800. NUS Press. p. 162. ISBN 978-9971695743.

- John N. Miksic (15 November 2013). Singapore and the Silk Road of the Sea, 1300-1800. NUS Press. p. 145-208. ISBN 978-9971695743.

- Abshire 2011, p. 18&19

- Heidhues 2001, p. 27

- Abshire 2011, p. 18

- John N. Miksic (15 November 2013). Singapore and the Silk Road of the Sea, 1300-1800. NUS Press. p. 148. ISBN 978-9971695743.

- Edwin Lee (15 October 2008). Singapore: The Unexpected Nation. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. pp. 1–2. ISBN 978-9812307965.

- Taylor 2000, p. 199

- Ooi 2004, p. 1311

- Leyden 1821, p. 52

- Leyden 1821, p. 52

- Sejarah Melayu, 5.4: 47: So the king of Majapahit ordered his war commander to equip vessels for attacking Singapore, a hundred jong; other than that a few melangbing and kelulus; jongkong, cecuruh, tongkang all in uncountable numbers.

- A. Samad 1979, p. 47

- Leyden 1821, p. 53

- Dr. John Leyden (1821). Malay Annals: Translated from the Malay Language. London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, and Brown. pp. 44–49.

- Dr. John Leyden (1821). Malay Annals: Translated from the Malay Language. London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, and Brown. pp. 83–85.

- Sejarah Melayu, 10.4:77: then His Majesty immediately ordered to equip three hundred jong, other than that kelulus, pelang, jongkong in uncountable numbers.

- A. Samad 1979, pp. 69–70

- Windstedt 1938, p. 32

- Miksic 2013, pp. 155–156

- A. Samad 1979, pp. 44–45

- Abshire 2011, p. 21

- Heng 2005, pp. 12–16

- Abshire 2011, p. 20

- Abshire 2011, p. 19

- Miksic 2013, pp. 163–164

- Miksic 2013, pp. 266;440-441

- Sinha 2006, p. 1526

- Miksic 2013, pp. 442-444

- Dr John Leyden and Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles (1821). Malay Annals.

- "The Maritime Experiential Museum". Resorts World Sentosa. December 2017. Retrieved 6 January 2019.

- Gua Zhen Tan (January 2018). "Artist behind muscular Sang Nila Utama said, yes, he is meant to look like this". Mothership.SG. Archived from the original on 18 January 2018. Retrieved 18 January 2018.

- "Sang Nila Utama, pioneers join Stamford Raffles along Singapore River". Channel NewsAsia. January 2019. Archived from the original on 4 January 2019. Retrieved 6 January 2019.

Bibliography

- A. Samad, Ahmad (1979), Sulalatus Salatin (Sejarah Melayu), Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka, ISBN 983-62-5601-6, archived from the original on 12 October 2013

- Abdul Rahman, Haji Ismail; Abdullah Zakaria, Ghazali; Zulkanain, Abdul Rahman (2011), A New Date on the Establishment of Melaka Malay Sultanate Discovered (PDF), Institut Kajian Sejarah dan Patriotisme ( Institute of Historical Research and Patriotism ), retrieved 4 November 2012

- Abshire, Jean E. (2011), The History of Singapore, Greenwood, ISBN 978-0-313-37742-6

- Aljunied, Syed Muhd Khairudin; Heng, Derek (2009), Reframing Singapore: Memory - Identity - Trans-Regionalism, Amsterdam University Press, ISBN 978-90-8964-094-9

- Commonwealth Secretariat (2004), Commonwealth Yearbook 2006, Commonwealth Secretariat, ISBN 978-0-9549629-4-4

- Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka (2010), Search: Singa, retrieved 6 December 2010

- Heng, Derek (2005), "Continuities and Changes : Singapore as a Port-City over 700 Years", Biblioasia, National Library Board, 1, ISSN 0219-8126

- Heidhues, Mary Somers (2001), Southeast Asia: A Concise History, Hudson and Thames, ISBN 978-0-500-28303-5

- Leyden, John (1821), Malay Annals (translated from the Malay language), Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme and Brown

- Miksic, John N. (15 November 2013), Singapore and the Silk Road of the Sea, 1300–1800, NUS Press, ISBN 978-9971695743

- Liow, Joseph Chinyong (2004), The Politics of Indonesia-Malaysia Relations: One Kin, Two Nations, Routledge, ISBN 978-0-415-34132-5

- O'Mara, Michael (1999), Facts About the World's Nation, H. W. Wilson, ISBN 978-0-8242-0955-1

- Ooi, Keat Gin (2004), Southeast Asia: a historical encyclopedia, from Angkor Wat to East Timor, ABC-CLIO, ISBN 1-57607-770-5

- Ooi, Keat Gin (2009), Historical Dictionary of Malaysia, Scarecrow Press, ISBN 978-0-8108-5955-5

- Sabrizain, Palembang Prince or Singapore Renegade?, retrieved 4 October 2012

- Sinha, Prakash Chandra (2006), Encyclopedia of South East and East Asia, Anmol Publications Pvt Ltd, ISBN 978-81-261-2646-0

- Taylor, Nora A. (2000), Studies on Southeast Asia (Studies on Southeast Asian Art: Essays in Honor of Stanley J. O'Connor), 29, Southeast Asia Program Publications, ISBN 978-0-87727-728-6

- Tsang, Susan; Perera, Audrey (2011), Singapore at Random, Didier Millet, ISBN 978-981-4260-37-4

- Windstedt, Richard Olaf (1938), "The Malay Annals or Sejarah Melayu", Journal of the Malayan Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, The Branch, XVI

.jpg)