Sultanate of Ternate

The Sultanate of Ternate, previously also known as The Kingdom of Gapi[1] is one of the oldest Muslim kingdoms in Indonesia besides Tidore, Jailolo, and Bacan. The Sultanate of Ternate was established by Momole Ciko, the first leader of Ternate, with the title Baab Mashur Malamo, in 1257.[1] It reached its Golden Age during the reign of Sultan Baabullah (1570–1583) and encompassed most of the eastern part of Indonesia and a part of southern Philippines. Ternate was a major producer of cloves and a regional power from the 15th to 17th centuries.

Sultanate of Ternate Kesultanan Ternate | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1257–1914 | |||||||

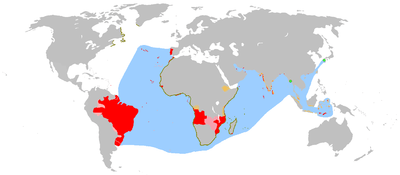

The extent of the Sultanate of Ternate | |||||||

| Capital | Ternate | ||||||

| Common languages | Ternate | ||||||

| Religion | Sunni Islam (after 1486) | ||||||

| Government | Sultanate | ||||||

| Sultan (Kolano before 1486) | |||||||

• 1257 – 1277 | Baab Mashur Malamo | ||||||

• 1902 – 1915 | Haji Muhammad Usman Shah | ||||||

• 2015 – present | Sjarifuddin Sjah | ||||||

| History | |||||||

• Founded | 1257 | ||||||

• Conversion to Islam | 1486 | ||||||

• Vassalisation by Dutch | 1683 | ||||||

• Final ruler dethroned by Dutch | 1914 | ||||||

• Honorary sultan crowned | 1927 | ||||||

| |||||||

| Today part of | |||||||

The dynasty founded by Baab Mashur Malamo continues to the present, as does the Sultanate itself, although it no longer holds any political power.

History

Pre-colonial period

The sultanate was originally named the Kingdom of Gapi[1], but later changed the name to be based on that of its capital, Ternate. Ternate and neighbouring Tidore were the world's single major producer of cloves, upon which their rulers became among the wealthiest and most powerful sultans in the Indonesian region.[2] Much of their wealth, however, was wasted fighting each other. Up until the Dutch completed the colonisation of Maluku in the 19th century, the Sultans of Ternate ruled empires that claimed at least nominal influence as far as Ambon, Sulawesi and Papua.[3]

In part as a result of its trade-dependent culture, Ternate was one of the earliest places in the region to which Islam spread, coming from Java in the late 15th century.[4] However, Islamic influence in the area can be traced further back to the late 14th century.[5] Initially, the faith was restricted to Ternate's small ruling family, and spread only slowly to the rest of the population.[4]

The royal family of Ternate converted to Islam during the reign of Marhum (1465–1486), making him the first King of Ternate that embraced Islam[1]; his son and successor, Zainal Abidin (1486–1500) enacted Islamic Law and transformed the kingdom into an Islamic Sultanate; the title Kolano (king) was then replaced with Sultan.

The peak of Ternate's power came near the end of the 16th century, under Sultan Baabullah (1570–1583), when it had influence over most of the eastern part of Sulawesi, the Ambon and Seram area, Timor island, parts of southern Mindanao and as well as parts of Papua. It frequently engaged in fierce competition for control of its periphery with the nearby Sultanate of Tidore. According to historian Leonard Andaya, Ternate's "dualistic" rivalry with Tidore is a dominant theme in the early history of the Maluku Islands.

16th century to the present

The first Europeans to stay on Ternate were part of the Portuguese expedition of Francisco Serrão out of Malacca, which was shipwrecked near Seram and rescued by local residents. Sultan Bayanullah of Ternate (1500–1522) heard of their stranding and, seeing a chance to ally himself with a powerful foreign nation, he brought them to Ternate in 1512. The Portuguese were permitted to build a fort on the island, today known as Kastella, construction of which began in 1522, but relations between the Ternateans and Portuguese were strained from the start.

An outpost far from Europe generally only attracted the most desperate and avaricious, such that the generally poor behaviour of the Portuguese, combined with feeble attempts at Christianisation, strained relations with Ternate's Muslim ruler.[6] In 1535 Sultan Tabariji was deposed and sent to Goa by the Portuguese. He converted to Christianity and changed his name to Dom Manuel. After being declared innocent of the charges against him he was sent back to re-assume his throne; however, he died en route in Malacca in 1545. He had though bequeathed the island of Ambon to his Portuguese godfather, Jordão de Freitas. Following the murder of Sultan Hairun at the hands of the Portuguese, the Ternateans expelled the Portuguese in 1575 after a five-year siege. Ambon became the new centre for Portuguese activities in Maluku. European power in the region was weak and Ternate became an expanding, fiercely Islamic and anti-Portuguese state under the rule of Sultan Baab Ullah (r. 1570–1583) and his son Sultan Said.[7]

Spanish forces captured the former Portuguese fort from the Ternatese in 1606, deporting the Ternate Sultan and his entourage to Manila in the Spanish Philippines. In 1607 the Dutch came back to Ternate, where with the help of Ternateans they built a fort in Malayo. The island was divided between the two powers: the Spaniards were allied with Tidore and the Dutch with their Ternaten allies. For the Ternaten rulers, the Dutch were a useful, if not particularly welcome, presence that gave them military advantages against Tidore and the Spanish. Particularly under Sultan Hamzah (1627–1648), Ternate expanded its territory and strengthened its control over the periphery. Dutch influence over the kingdom was limited, though Hamzah and his grandnephew and successor, Sultan Mandar Syah (1648–1675) did concede some regions to the Dutch East India Company (VOC) in exchange for help controlling rebellions there. The Spaniards abandoned Maluku in 1663.

Desiring to restore Ternate to its former glory and expel the western power, Sultan Sibori Amsterdam (1675–1691) declared war to the Dutch, but the power of Ternate had greatly reduced over the years, he lost and was forced to concede more of his lands to the Dutch by a treaty in 1683. By this treaty, Ternate had lost its equal position with the Dutch and became a vassal. However, the Sultans of Ternate and its people were never fully under Dutch control until its annexation in 1914.

In the 18th century Ternate was the site of a VOC governorship, which attempted to control all trade in the northern Moluccas. By the 19th century, the spice trade had declined substantially. Hence the region was less central to the Netherlands colonial state, but the Dutch maintained a presence in the region to prevent another colonial power from occupying it. After the VOC was nationalised by the Dutch government in 1800, Ternate became part of the Government of the Moluccas (Gouvernement der Molukken). Ternate was seized and occupied by British forces in 1810 before being returned to Dutch control in 1817. In 1824 it became the capital of a residency (administrative region) covering Halmahera, the entire west coast of New Guinea, and the central east coast of Sulawesi. By 1867 all of Dutch-occupied New Guinea had been added to the residency, but then its region was gradually transferred to Ambon (Amboina) before being dissolved into that residency in 1922.

Sultan Haji Muhammad Usman (1896–1914) made a last attempt to drive out the Dutch by instigating revolts in the region; he failed and was dethroned, his wealth being confiscated, and he was exiled to Bandung, where he lived his remaining years until 1927. The throne of Ternate was left vacant from 1914 to 1927, until the board of ministers under the blessing of the Dutch created Crown Prince Iskandar Muhammad Jabir the next Sultan.

Sultan Mudaffar Sjah II died in 2015. The male members of his wife's family, the Dutch Van Gelders, were named Prince of Ternate in 2012, and rule the island since Mudaffar's death.

List of Sultans

| Kolano of Ternate | Reign |

|---|---|

| Baab Mashur Malamo | 1257–1277 |

| Poit [Jamin Qadrat] | 1277–1284 |

| Komala 'Abu Said [Siale] | 1284–1298 |

| Bakuku [Kalabata] | 1298–1304 |

| Ngara Malamo [Komala] | 1304–1317 |

| Patsaranga Malamo [Aitsi] | 1317–1322 |

| Cili Aiya [Sidang Arif Malamo] | 1322–1331 |

| Panji Malamo [A'ali] | 1331–1332 |

| Shah Alam | 1332–1343 |

| Tulu Malamo [Fulu] | 1343–1347 |

| Kie Mabiji [Buhayati I] | 1347–1350 |

| Ngolo-ma-Kaya [Muhammad Shah] | 1350–1357 |

| Mamoli [Momole] | 1357–1359 |

| Gapi Malamo I [Muhammad Bakar] | 1359–1372 |

| Gapi Baguna I | 1372–1377 |

| Komala Pulu [Bessi Muhammad Hassan] | 1377–1432 |

| Marhum [Gapi Baguna II] | 1432–1486 |

| Zainal Abidin | 1486–1500 |

| Bayan Sirrullah | 1500–1522 |

| Abu Hayat | 1522–1529 |

| Hidayatullah | 1529–1533 |

| Tabariji | 1533–1535 |

| Hairun Jamilu | 1535–1570 |

| Babullah Datu Shah | 1570–1583 |

| Said Barakat Shah | 1583–1606 |

| Muzaffar Shah I | 1607–1627 |

| Hamzah | 1627–1648 |

| Mandar Shah [Manlarsaha] | 1648–1650 |

| Manilha | 1650–1651 |

| Mandar Shah | 1651–1675 |

| Sibori Amsterdam | 1675–1689 |

| Said Fathullah | 1689–1714 |

| Amir Iskandar Zulkarnain Saifuddin | 1714–1751 |

| Ayan Shah | 1751–1754 |

| Syah Mardan | 1755–1763 |

| Jalaluddin | 1763–1774 |

| Harun Shah | 1774–1781 |

| Achral | 1781–1796 |

| Muhammad Yasin | 1796–1801 |

| Muhammad Ali | 1807–1821 |

| Muhammad Sarmoli | 1821–1823 |

| Muhammad Zain | 1823–1859 |

| Muhammad Arsyad | 1859–1876 |

| Ayanhar | 1879–1900 |

| Muhammad Ilham [Kolano Ara Rimoi] | 1900–1902 |

| Haji Muhammad Usman Shah | 1902–1915 |

| Iskandar Muhammad Jabir Shah | 1929–1975 |

| Haji Muzaffar Shah II [Dr Mudaffar Syah] | 1975–2015 |

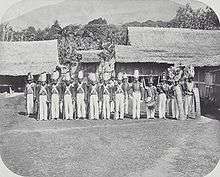

Palace

The existing sultan's palace was built in 1796 and restored in a semi-colonial style and is now partly a museum as well as the sultan's home. The museum exhibits the genealogy of the Ternatean royal family from 1257, a collection of Portuguese and Dutch helmets, swords and armour, and memorabilia from the previous sultans.

Legacy

The eastern Indonesian archipelago empire led by Ternate had indeed fallen apart since the middle of the 17th century but the influence of Ternate as a kingdom with a long history continued to be felt until centuries later. Ternate has a very large share in the eastern archipelago culture, especially Sulawesi (north and east coast) and Maluku. These influences include religion, customs and language.

As the first kingdom to embrace Islam, Ternate had a large role in the efforts to convert and introduce Islamic Sharia in the eastern part of the archipelago and the southern part of the Philippines. The form of the organization of the empire and the application of Islamic law which was first introduced by Sultan Zainal Abidin became the standard followed by all the kingdoms in Maluku almost without significant changes.

The success of the Ternate people under Sultan Baabullah in expelling Portugal in 1575 was the first indigenous victory of the archipelago over western powers, therefore Buya Hamka even praised the victory of the Ternate people for delaying the western occupation of the archipelago for 100 years while at the same time strengthening the position of Islam, and if the people Ternate is undoubtedly the eastern part of Indonesia will become a Christian center like the Philippines.

The position of Ternate as an influential kingdom also helped raise the degree of Ternate Language as the language of association in various regions which were under its influence. Prof. E.K.W. Masinambow in his writings, "Ternate Language in the context of Austronesian and Non-Austronesian languages" suggested that Ternate had the greatest impact on the Malay language used by the people of eastern Indonesia. 46% of Malay vocabulary in Manado is taken from Ternate. Ternate Malay or North Moluccan Malay language is now widely used in Eastern Indonesia, especially in North Sulawesi, the east coast of Central and South Sulawesi, Maluku and Papua with different dialects.

Two manuscripts of the Ternate sultan's letter, from Sultan Abu Hayat II to the King of Portugal on 27 April and 8 November 1521 were recognized as the oldest Malay manuscripts in the world after the Tanjung tanah manuscripts. The two letters of Sultan Abu Hayat are currently still stored in the Museum of Lisbon, Portugal.

See also

- Spice trade

- List of Sunni Muslim dynasties

- List of rulers of Maluku

References

- "Sejarah Kesultanan Ternate: Kerajaan Islam Tertua di Maluku Utara". tirto.id (in Indonesian). Retrieved 17 August 2019.

- Witton, Patrick (2003). Indonesia (7th edition). Melbourne: Lonely Planet. p. 821. ISBN 1-74059-154-2.

- Federspiel, Howard M. (2007). Sultans, Shamans, and Saints: Islam and Muslims in Southeast Asia. University of Hawaii Press. p. 52. ISBN 978-0-8248-3052-6.

- Azra, Azyumardi (2006). Islam in the Indonesian World: An Account of Institutional Formation. Mizan Pustaka. pp. 39–40. ISBN 978-979-433-430-0.

- Ricklefs, M.C. (1993). A History of Modern Indonesia Since c. 1300, 2nd Edition. London: MacMillan. p. 24. ISBN 0-333-57689-6.

- Ricklefs, M.C. (1993). A History of Modern Indonesia Since c. 1300, 2nd Edition. London: MacMillan. p. 25. ISBN 0-333-57689-6.