Lavo Kingdom

The Kingdom of Lavo was a political entity (mandala) on the left bank of the Chao Phraya River in the Upper Chao Phraya valley from the end of Dvaravati civilization, around the 7th century, until 1388. The original center of Lavo civilization was Lavo (modern Lopburi), but the capital shifted southward to Ayutthaya around the 11th century, whereupon the state became the Ayutthaya Kingdom according to recent historical analysis.

Kingdom of Lavo | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 450–1388 | |||||||||||

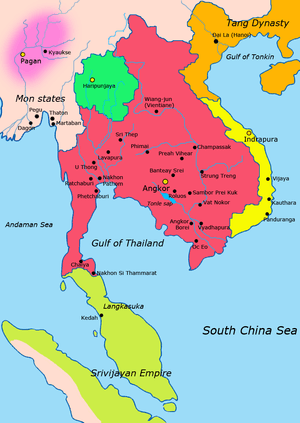

1000–1100 Light Blue: Lavo Kingdom Red: Khmer Empire Green: Hariphunchai Light Green: Srivijaya Yellow: Champa Blue: Đại Việt Pink: Pagan Kingdom | |||||||||||

| Capital | Lavo (450–1087) Ayutthaya (1087–1388) | ||||||||||

| Common languages | Old Mon Old Khmer Old Thai | ||||||||||

| Religion | Hinduism Theravada Buddhism Mahayana Buddhism | ||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||

| Emperor | |||||||||||

| Legislature | Ahabhushan Mahakosh | ||||||||||

| Historical era | Middle Ages | ||||||||||

• Formation | 450 | ||||||||||

• Annexed into Ayutthaya Kingdom | 1388 | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

History

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Thailand |

|

|

Legendary Suvarnabhumi Central Thailand Dvaravati Lavo Supannabhum Northern Thailand Singhanavati Ngoenyang Hariphunchai Lanna Southern Thailand Pan Pan Raktamaritika Langkasuka Srivijaya Tambralinga Nakhon Si Thammarat Sultanate of Pattani Kedah Sultanate Malacca Sultanate Satun Reman |

| History |

|

Regional history |

|

Related topics

|

|

|

Background

Dvaravati and Mon domination

The area of Dvaravati (what is now Thailand) was first inhabited by Mon people who had arrived and appeared centuries earlier. The foundations of Buddhism in central Southeast Asia were laid between the 6th and 9th centuries when a Theravada Buddhist culture linked to the Mon people developed in central and northeastern Thailand. Theravadans believe that enlightenment can be obtained only by one living the life of a monk (and not by a layman). Unlike Mahayana Buddhists, who admit the texts of numerous Buddhas and Bodhisattvas into canon, Theravadans venerate only the Buddha Gautama, the founder of the religion. The Mon Buddhist kingdoms that rose in what are now parts of Laos and Central Plain of Thailand were collectively called Dvaravati.[1]:27

The Mon of Lavo

The legendary first king of Lavo, Phraya Kalavarnadit, a Mon ruler, was said to have established the city around 450 CE[2] as one of the Dvaravati city-states. Kalavarnadit established a new era called the Chula Sakarat, which was the era used by the Siamese and the Burmese until the 19th century.

Kalavarnadit used the name "Lavo" as the name of the kingdom, which came from the Hindu name "Lavapura", meaning "city of Lava", in reference to the ancient South Asian city of Lavapuri (present-day Lahore).[3]

The only native language found during early Lavo times is the Mon language. However, there is debate whether Mon was the sole ethnicity of Lavo. Some historians point out that Lavo was composed of mixed Mon and Lawa people (a Palaungic-speaking people),[4][5] with the Mons forming the ruling class. It is also hypothesized that the migration of Tai peoples into Chao Phraya valley occurred during the time of the Lavo kingdom.

Theravada Buddhism remained a major belief in Lavo although Hinduism and Mahayana Buddhism from the Khmer Empire wielded considerable influence.[6] Around the late 7th century, Lavo expanded to the north. In the Northern Thai Chronicles, including the Cāmadevivaṃsa, Camadevi, the first ruler of the Mon kingdom of Hariphunchai, was said to be a daughter of a Lavo king.

Few records are found concerning the nature of the Lavo kingdom. Most of what we know about Lavo is from archaeological evidence. Tang dynasty chronicles record that the Lavo kingdom sent tributes to Tang as Tou-ho-lo. In his diary, the monk Xuanzang referred to Dvaravati-Lavo as Tou-lo-po-ti, which seems to echo the name Dvaravati, as a state between Chenla and the Pagan Kingdom. By the Song dynasty, Lavo was known as Luówō (Chinese: 羅渦).

Khmer domination

Isanavarman I of the Chenla Kingdom expanded Khmer influence to the Chao Phraya valley through his campaigns around the 7th century.[7] Dvaravati cities that fell under Khmer hegemony became Lavo, while the Western cities were spared from Khmer hegemony and formed Suvarnabhumi.[8] Lavo was the center from which Khmer authority ruled over the Dvaravati.

Around the 10th century, the city-states of Dvaravati merged into two mandalas – the Lavo (modern Lopburi) and Suvarnabhumi (modern Suphan Buri). According to a legend in the Northern Chronicles, in 903, a king of Tambralinga invaded and took Lavo and installed a Malay prince to the Lavo throne. The Malay prince was married to a Khmer princess who had fled an Angkorian dynastic bloodbath. The son of the couple contested for the Khmer throne and became Suryavarman I, thus bringing Lavo under Khmer domination through personal union. Suryavarman I also expanded into Isan, constructing many temples.

Arrival of Tai

Modern Thai historians think the Tai peoples originated in northern Vietnam and Guangxi province in China.[9] The origin of the Tai peoples were living in northern Southeast Asia by the 8th century.[10] Five linguistic groups emerged: the northern Tai in China (ancestors of Zhuang); the upland Tai people in northern Vietnam (ancestors of the Black, White and Red Tai); the Tais in northeastern Laos and bordering Vietnam (ancestors of the Tai of Siang Khwang and the Siamese in Ayutthaya); the Tai in northern Laos; and the Tai west of Luang Prabang, northern Thailand and in the adjoining parts of Laos, Yunnan and Burma.[1]:26 The Tai people had emigrated in the area what is now Thailand around 11th century, the land was already inhabited by Mon and Khmer speaking peoples, who had arrived earlier.

Tai Villages and Mueang

Tai peoples lived in the lowland and river valleys of mainland Southeast Asia. Assorted ethnic and linguistic group lived in the hills. The Tai village consisted of nuclear families working as subsistence rice farmers, living in small houses elevated above the ground. Households bonded together for protection from external attacks and to share the burden of communal repairs and maintenance. Within the village, a council of elders was created to help settle problems, organise festivals and rites and manage the village. Village would combine to form a Mueang (Thai: เมือง), a group of villages governed by a Chao (Thai: เจ้า) (lord).[1]:25 When Tai people settled in Central Plain of Thailand, the Cambodian ruler saw Tai people as barbarian, who came from China, and named them as Siem (Khmer: សៀម) in Khmer language. The Tai lords adopted both Mon alphabet and Khmer alphabet, which the Tai developed into their own writing systems as Tai Tham alphabet, for the Thai Yuan people in the north, and Khom-Thai alphabet, for the Siamese Tai in the lower region. The Siamese also called themselves as Tai or Thai and called Lavo as "Lopburi" in Tai dialect language.

Settled in the rural fringes of the Khmer Empire and in upper Laos, the Tai peoples, united by their lords, were becoming a formidable threat to the Khmer Empire. Despite intermarriage between the Tai and the Khmer ruling families, the Tai people kept their distinct cultural and ethnic identity, retaining their own languages and units of social organisation.

Tai city states appearance

Siamese Lopburi (11th century)

The formidable political control exercised by the Angkor Empire extended not only over the centre of the Khmer province, where the majority of the population was Khmer, but also to outer border provinces likely populated by non-Khmer peoples—including areas to the north and northeast of modern Bangkok, the lower central plain and the upper Pink river in the Lamphun-Chiang Mai region.[1]:28

The Tai people were the predominant non-Khmer groups in the areas of central Thailand that formed the geographical periphery of the Khmer Empire. Tai groups were probably assimilated into Khmer population. Historical records show that they maintained their cultural distinctiveness, although their animist religion partially gave way to Buddhism. Tai historical documents note that the period of the Angkor Empire was one of great internal strife. During the 11th and 12th centuries, territories with a strong Tai presence, such as Lopburi (in what is now north-central Thailand), resisted Khmer control.[1]:28

In the 11th century, Lopburi was governed by a Cambodian prince, as a part of vassal state of the Khmer Empire of Angkor, However, Lopburi wanted liberation and sought acknowledgement from China (Song dynasty) in 1001 and 1155 as an independent state. Lopburi's large Tai population and its roots in the Dvaravati did not assimilate well with the Khmer civilisation, and in Khmer writings Lopburi was considered a province of Angkor that had a Syamese (Siamese) identity.[1]:29

The Khmer influences on Lavo began to wane as a result of the growing influence of the emerging Burmese kingdom of Pagan. In 1087 Kyansittha of Pagan invaded Lavo, but King Narai of Lavo was able to repel the Burmese invasion and Lavo, emerging relatively stronger from the encounter, was thus spared from either Khmer or Burmese hegemony. King Narai moved the capital to Ayodhaya[11] and Lavo was then able to exert pressure on Suvarnabhumi to the west and slowly to take its cities.

Yet another wave of Khmer invasions arrived under Jayavarman VII. This time, Lavo was assimilated into the religious cosmos of the Khmer Empire – Hinduism and Mahayana Buddhism. Khmer influence was great on Lavo arts and architecture as seen in the Prang Sam Yot.

In 1239, the Tai governor of Sukhothai rebelled and declared independence from Lavo – giving birth to the Sukhothai Kingdom. In Thai chronicles Lavo is called “Khmer”, and during the 13th century the Lavo kingdom shrank swiftly due to the expansion of Sukhothai under Ram Khamhaeng the Great, retreating to its heartland around Lavo and Ayodhaya.

The Kingdom of Lavo, Lo-hu, sent embassies to China between 1289 and 1299.[12]:221–222

King Vorachet, the tenth king of Ayodhaya (counting King Narai as the first) is hypothesized to be the same person as Uthong of the Ayutthaya kingdom.[11] Uthong of Lavo and Borommarachathirat I of Suvarnabhumi co-founded a new Ayutthaya, and Uthong became the king of the city. But Pa Ngua took Ayutthaya from Uthong's son Ramesuan in 1370 and Ramesuan returned to his homeland at Lavo. In 1388 Ramesuan took revenge by taking Ayutthaya back from Pa Ngua's son, Thonglan.

Pa Ngua's nephew Intharacha took Ayutthaya back for Suvannabhum in 1408. The Lavo dynasty was then purged and became a mere noble family of Ayutthaya until the 16th century.

See also

References

- Ellen London, 2008, Thailand Condensed 2000 years of history and culture, Singapore: Marshall Cavendish Editions, ISBN 9789812615206

- Archived May 26, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- Phanindra Nath Bose, The Indian colony of Siam, Lahore, The Punjab Sanskrit Book Depot, 1927, p.v.

- "The Kingdom of Syam". Meruheritage.com. Retrieved 2015-12-14.

- John Pike. "Thailand - 500-1000 - Lavo / Lopburi". Globalsecurity.org. Retrieved 2015-12-14.

- Archived August 28, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- "๏ฟฝาณาจัก๏ฟฝ๏ฟฝ๏ฟฝ๏ฟฝาณ". Webcitation.org. Archived from the original on October 26, 2009. Retrieved 2015-12-14.CS1 maint: unfit url (link)

- Pittayaporn, Pittayawat (2014). Layers of Chinese Loanwords in Proto-Southwestern Tai as Evidence for the Dating of the Spread of Southwestern Tai Archived 27 June 2015 at the Wayback Machine. MANUSYA: Journal of Humanities, Special Issue No 20: 47–64.

- Pittayaporn 2014, pp. 47–64.

- Archived August 22, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- Coedès, George (1968). Walter F. Vella (ed.). The Indianized States of Southeast Asia. trans.Susan Brown Cowing. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-0368-1.