Buddhism in Malaysia

Buddhism is the second largest religion in Malaysia, after Islam, with 19.8% of Malaysia's population being Buddhist[1][2] although some estimates put that figure at 21.6% when combining estimates of numbers of Buddhists with figures for adherents of Chinese religions which incorporate elements of Buddhism.[3] Buddhism in Malaysia is mainly practised by the ethnic Malaysian Chinese, but there are also Malaysian Siamese, Malaysian Sri Lankans and Burmese in Malaysia that practice Buddhism such as Ananda Krishnan and K. Sri Dhammananda and a sizeable population of Malaysian Indians.

| Part of a series on |

| Buddhism |

|---|

|

|

|

|

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 5,620,483 (2010) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Languages | |

| Religion | |

| |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Malaysia Hindus |

History

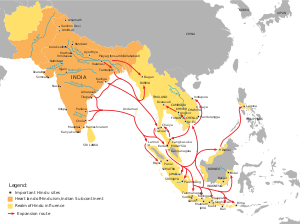

Buddhism was introduced to the Malays and also to the people of the Malay Archipelago as early as 200 BCE. Chinese written sources indicated that some 30 small Indianised states rose and fell in the Malay Peninsula. Malay-Buddhism began when Indian traders and priests traveling the maritime routes and brought with them Indian concepts of religion, government, and the arts. For many centuries the peoples of the region, especially the royal courts, synthesised Indian and indigenous ideas including Hinduism and Mahayana Buddhism and that shaped their political and cultural patterns.[4] However, the Malay Kedah Kingdom denounced Indian religion after the king of Chola from Tamil Nadu attacked them in the early 11th century. The king of Kedah, Phra Ong Mahawangsa, was the first Malay ruler to denounce the traditional Indian religion; he converted to Islam, and in the 15th century, during the golden age of the Malacca Sultanate, the majority of Malays converted to Islam.

Status

%2C_Sentul%2C_Kuala_Lumpur.jpg)

According to the Malaysian constitution, the majority ethnic group, the Malays, are legally defined as Muslim. They constitute 60% of the population, with the remainder consisting mostly of Chinese, who are generally Buddhists or Christians, and to the lesser extent Indians, who are generally Hindus. There are also smaller numbers of other indigenous and immigrants; among the latter are Malaysians of Sinhalese, Thai, and Eurasian origin. Nearly all of the Buddhists in Malaysia live in urban areas, since they are mostly engaged in business or employed in various professions.

Recently, a number of Malaysian Buddhist leaders have responded to the decline in religious participation by the children of Buddhist families, have attempted to reformulate their message to address modern life more directly. Groups involved in these education efforts include the Buddhist Missionary Society. Missionary Society leaders have argued that, while many educated youths seek an intellectual approach to Buddhism, an equally large number of people prefer to approach the religion through the tradition of ceremony and symbolism. In response to these needs, religious practices are carried out, but in a way that is simple and dignified, removing what can be seen as superstition. Efforts are made to explain why sutras are chanted, lamps lit, flowers offered, and so on.

As a religion without a supreme head to direct its development, Buddhism is practised in various forms, which, although rarely in open conflict, can sometimes lead to confusion among Buddhists. In Malaysia, some ecumenical moves have been made to coordinate the activities of different types of Buddhists. One example is the formation of the Joint Wesak Celebrations Committee of the temples in Kuala Lumpur and Selangor, which coordinates the celebration of Wesak, a holiday commemorating the birth of the Buddha. An initiative has also begun to form a Malaysian Buddhist Council, representing the various sects of Buddhism in the country to extend the work of the development of Buddhism, especially in giving contemporary relevance to the practise of the religion, as well as to promote solidarity among Buddhists in general.

In 2013, a video of a group of Buddhist practitioners from Singapore conducting religious ceremonies in a surau had become viral on Facebook. Malaysian police have arrested a resort owner after he allowed 13 Buddhists to use a Muslim prayer room (surau) for their meditation at Kota Tinggi, Johor.[5] The incident has been a frown upon Muslims in Malaysia. It has also become a hot topic in the social media. Following up at 28 August 2013, the controversial prayer room was demolished by the resort management within 21 days from the date of receipt of the notice after much protests by the residents of Kota Tinggi.[6][7] At the time, Syed Ahmad Salim, the resort owner explained that he had allowed the group of Buddhists to use the surau for a meditation session as he was unaware that it was an offence.[8]

Distribution of Buddhists

According to the 2010 Census, 5,620,483 people or 19.8% of the population identify themselves as Buddhists. Most Chinese Malaysian follow a combination of Buddhism, Taoism, Confucianism and ancestor-worship but, when pressed to specify their religion, will identify themselves as Buddhists. As a result, 83.6% of all the Chinese Malaysian self-identifying as Buddhist. Information collected in the census based on respondent's answer and did not refer to any official document.

By gender and ethnic group

| Gender | Total Buddhist Population (2010 Census) | Malaysian Buddhist Citizens | Non-Malaysian Buddhist Citizens | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bumiputera Buddhist | Non-Bumiputera Buddhist | ||||||

| Malay Buddhist | Other Bumiputera Buddhist | Chinese Buddhist | Indian Buddhist | Others Buddhist | |||

| Nationwide | 5,620,483 | 0 | 33,663 | 5,341,687 | 32,441 | 51,274 | 161,418 |

| Male Buddhist | 2,903,709 | 0 | 16,611 | 2,759,151 | 16,888 | 25,429 | 91,630 |

| Female Buddhist | 2,716,774 | 0 | 17,052 | 2,588,536 | 15,553 | 25,845 | 69,788 |

By state or federal territory

| State | Total Buddhist population (2010 Census) | % of State Population |

|---|---|---|

| Johor | 989,316 | 29.5% |

| Kedah | 275,632 | 14.2% |

| Kelantan | 57,792 | 3.8% |

| Kuala Lumpur | 597,770 | 35.7% |

| Labuan | 7,795 | 9.0% |

| Malacca | 198,669 | 24.2% |

| Negeri Sembilan | 216,325 | 21.2% |

| Pahang | 215,815 | 14.4% |

| Penang | 556,293 | 35.6% |

| Perak | 597,870 | 25.4% |

| Perlis | 22,980 | 9.9% |

| Putrajaya | 273 | 0.4% |

| Selangor | 1,330,989 | 24.4% |

| Terengganu | 25,653 | 2.5% |

| Sarawak | 332,883 | 13.5% |

| Sabah | 194,428 | 6.1% |

Persecution of Buddhists in Malaysia

Human rights of religious and ethnic minorities in Malaysia, including Buddhists, Hindus, Sikhs, Indians and Malaysian Chinese, are systematically, officially and legally violated regularly in an institutionalised manner.

Islamist supremacist sharia and Bigoted Bumiputera laws

Islam is the official religion of Malaysia. The constitution of Malaysia declares that Islam is the only religion of true Malay people and that natives are required to be Muslims.[9] Conversion from Islam to Hinduism (or another religion) is against the law, but the conversion of Hindus, Buddhists, and Christians to Islam is actively pursued through institutionalised means and unfair anti-nonmuslim laws. The government actively promotes the conversion to Islam in the country.[10] The anti-minorities discriminatory law requires that any nonmuslims (Hindu or Buddhist or Christian) who marries a Muslim must first convert to Islam, otherwise the marriage is illegal and void.[10] If one of the Hindu parents adopts Islam, the children forcibly and automatically decalred as Muslim without the consent of the second parent.[11][12]

Destruction of temples

Several Buddhist and Hindu temples were demolished by the government as they were built on government land which have been redeveloped in recent times.

Notable people

Kirinde Sri Dhammaratana

Kirinde Sri Dhammaratana

See also

- Bujang Valley, an ancient Hindu-Buddhist civilisation centred on Kedah

- Malaysian Vajrayana

- Malaysia Hindus

- Jainism in Southeast Asia

- Hinduism in Southeast Asia

- Chi Chern

References

- "Taburan Penduduk dan Ciri-ciri Asas Demografi" (PDF). Jabatan Perangkaan Malaysia. p. 82. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 November 2013. Retrieved 25 March 2013.

- "Population Distribution and Basic Demographic Characteristic Report 2010 (Updated: 05/08/2011)". Department of Statistics, Malaysia. Retrieved 11 March 2017.

- "The World Factbook: Malaysia". CIA World Factbook. Retrieved 2007-11-22.

- "Early Malay Kingdoms". Sabrizain.org. Retrieved 2016-04-29.

- "S'porean held in Malaysia after Buddhists use Muslim prayer room". YouTube. 2013-08-12. Retrieved 2016-04-29.

- "Surau in Kota Tinggi resort demolished". The Star Online. August 28, 2013. Retrieved August 28, 2013.

- "Surau kontroversi diroboh(Malay)". Kosmo!. August 28, 2013. Archived from the original on April 5, 2015. Retrieved August 28, 2013.

- "One year after surau controversy, normalcy returns to Johor resort". Kosmo!. 23 October 2014. Archived from the original on 24 October 2014. Retrieved 23 October 2014.

- Sophie Lemiere, apostasy & Islamic Civil society in Malaysia, ISIM Review, Vol. 20, Autumn 2007, pp. 46-47

- Gill & Gopal, Understanding Indian Religious Practice in Malaysia, J Soc Sci, 25(1-2-3): 135-146 (2010)

- 2011 Report on International Religious Freedom - Malaysia U.S. State Department (2012)

- Perry Smith (2003), Speak No Evil: Apostasy, Blasphemy, and Heresy in Malaysian Syariah Law, UC Davis Journal Int'l Law & Pol'y, 10, pp. 357-399

- Sam Littlefair (13 August 2015). "Actor Michelle Yeoh blends Buddhism & activism". Lion's Roar. Retrieved 21 January 2019.

- "Thousands pay homage to Buddha in Malaysia". Buddhist Channel. 20 May 2008. Retrieved 21 January 2019.

Bibliography

- Lee, Raymond L. M.; Ackerman, Susan Ellen (1997). "In Search of Nirvana", in: Sacred Tensions: Modernity and Religious Transformation in Malaysia. University of South Carolina Press. pp. 57–88. ISBN 978-1-57003-167-0.