Founding of modern Singapore

The founding of modern Singapore is said to have started with the establishment of a British trading post in Singapore in 1818 to 1819 by Sir Stamford Raffles and its founding as a British colony in 1824 has generally been understood to mark the founding of colonial Singapore,[1] a break from its status as a port in ancient times during the Srivijaya and Majapahit eras, and later, as part of Melaka and Johor.

Part of a series on the |

||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| History of Singapore | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Early history (pre-1819)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

British colonial era (1819–1942)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Japanese Occupation (1942–1945)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Post-war period (1945–1962)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Internal self-government (1955–1963)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Merger with Malaysia (1963–1965) |

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Republic of Singapore (1965–present)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

Pre-colonial Singapore

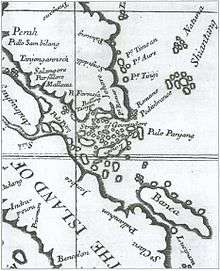

A significant port and settlement, known as Temasek, later renamed Singapura, existed on the island of Singapore in the 14th century. Vietnamese records indicate possible diplomatic relationship between Temasek and Vietnam in the 13th century,[2] and Chinese documents describe settlements there in the 14th century.[3] It was likely a vassal state of both the Majapahit Empire and the Siamese at different times in the 14th century.[4] Around the end of the 14th century, its ruler Parameswara was attacked by either the Majapahit or the Siamese, forcing him to move on to Melaka where he founded the Sultanate of Malacca,[5] Archaeological evidence suggests that the main settlement on present-day Fort Canning was abandoned around this time, although a small-scale trading settlement continued in Singapore for some time afterwards.[6] Between the 16th and 19th centuries, the Malay archipelago was gradually taken over by the European colonial powers, beginning with the Portuguese conquest of the Malacca Sultanate in 1511. In 1613, the Portuguese burnt down a trading settlement at the mouth of the Singapore River, after which Singapore lapsed into insignificance in the history of the region for two hundred years.[7]

The early dominance of the Portuguese was challenged during the 17th century by the Dutch, who came to control most of the region's ports. The Dutch established a monopoly over trade within the archipelago, particularly in spices, then the region's most important product. Other colonial powers, including the British, were limited to a relatively minor presence in that period.

Singapore's name comes from 'Singa Pura' which means Lion City in Sanskrit and 'Singam oor' which means city of lions in Tamil. According to the Sejarah Melayu (Malay Annals), a Sumatran prince called Sang Nila Utama landed on Temasek[8] (Singapore's old name) and saw a Lion which is called 'Singa' in Malay. Thus he gave the island a new name, 'Singapura'.[9]

Raffles' landing and arrival

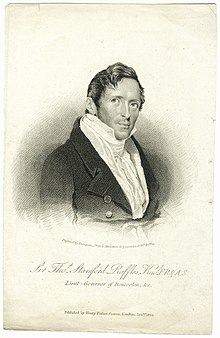

In 1818, Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles was appointed Lieutenant Governor of the British colony at Bencoolen. Raffles believed that the British should find a way to challenge the dominance of the Dutch in the area. The trade route between China and British India passed through the Malacca Strait, and with the growing trade with China, that route would become increasingly important. However, the Dutch had tight control over the trade in the region and intended to enforce the exclusive rights of its company ships to trade, and that trade should be conducted at its entrepot Batavia. British trading ships were heavily taxed at Dutch ports, stifling British trade in the region.[10][11]

Raffles reasoned that the way to challenge the Dutch was to establish a new port in the region. Existing British ports were not in a strategic enough position to becoming major trading centres. Penang was too far north of the southern narrow part of Straits of Malacca controlled by the Dutch, whereas Bencoolen faced the Indian Ocean near the Sunda Strait, a much less important area as it is too far away from the main trading route.[12] Many other possible sites were either controlled by the Dutch, or had other problems.

In 1818, Raffles managed to convince Lord Hastings, the then governor-general of India and his superior in the British East India Company, to fund an expedition to establish a new British base in the region, but with the proviso that it should not antagonise the Dutch.[11] Raffles then searched for several weeks. He found several islands that seemed promising, but were either already occupied by the Dutch, or lacked a suitable harbour.

Eventually Raffles settled on the island of Singapore, because of its position at the southern tip of the Malay peninsula, near the Straits of Malacca, and its excellent natural harbor, fresh water supplies, and timber for repairing ships. Most importantly, it was unoccupied by the Dutch.[11]

Raffles' expedition arrived in Singapore on 29 January 1819 (although they landed on Saint John's Island the previous day).[13] He found a Malay settlement at the mouth of the Singapore River, headed by Temenggong Abdul Rahman for the Sultan of Johor. The Temenggong had originally moved to Singapore from Johor in 1811 with a group of Malays, and when Raffles arrived, there were an estimated 150 people governed by the Temenggong, mostly of them Malays, with around 30 Chinese.[14] Although the island was nominally ruled by Johor, the political situation was precarious for the Sultan of Johor at the time. The incumbent Sultan of Johor, Tengku Abdul Rahman, was controlled by the Dutch and the Bugis, and would never agree to a British base in Singapore. However, Abdul Rahman was Sultan only because his older brother, Tengku Hussein, also known as Tengku Long, had been away in Pahang getting married when their father died. Hussein was then living in exile in the Riau Islands.[15]

Singapore Treaty

With the Temenggong's help, Raffles smuggled Tengku Hussein to Singapore. He offered to recognize Hussein as the rightful Sultan of Johor, and provide him with a yearly payment; in return, Hussein would grant the British East India Company the right to establish a trading post on Singapore.[11] In the agreement, Sultan Husain would receive a yearly sum of 5,000 Spanish dollars, with the Temenggong receiving a yearly sum of 3,000 Spanish dollars.[16] This agreement was ratified with a formal treaty signed on 6 February 1819.[17][18]

Early growth (1819–1826)

Raffles returned to British Bencoolen (Sumatra) the day after the signing of the treaty, leaving Major William Farquhar as the Resident and Commandant of the new settlement,[16] supported initially by some artillery and a single regiment of Indian soldiers. Establishing a trading port from scratch was in itself a daunting prospect, but Farquhar's administration was, in addition, practically unfunded, as Raffles did not wish his superiors to view Singapore as a liability. In addition, it was forbidden from earning revenue by imposing port duties, Raffles having decided from the outset that Singapore would be a free port.[11]

In spite of these difficulties, the new colony rapidly proved to be a spectacular success. As news of the free port spread across the archipelago, Bugis, Peranakan Chinese, and Arab traders flocked to the island, seeking to circumvent the Dutch trading restrictions. During the first year of operation, $400,000 (Spanish dollars) worth of trade passed through Singapore. It has been estimated that when Raffles arrived in 1819, the total population of the whole of Singapore was around a thousand, mostly of various local tribes.[20] By 1821, the island's population had increased to around five thousand, and the trade volume was $8 million. By 1825, the population had passed the ten thousand mark, with a trade volume of $22 million. (By comparison, the trade volume for the long-established port of Penang was $8.5 million during the same year.)[11]

Raffles returned to Singapore in 1822. Although Farquhar had successfully led the settlement through its difficult early years, Raffles was critical of many of the decisions he had made. For instance, in order to generate much-needed revenue for the government, Farquhar had resorted to selling licenses for gambling and the sale of opium, which Raffles saw as social evils. Raffles was also appalled by the slave trade tolerated by Farquhar.[21] Raffles arranged for the dismissal of Farquhar, who was replaced by John Crawfurd. Raffles took over the administration himself, and set about drafting a set of new policies for the settlement.[22]

Raffles banned slavery, closed all gambling dens, prohibited the carrying of weapons, and imposed heavy taxation to discourage what he considered vices such as drunkenness and opium smoking.[22] Raffles, dismayed at the disarray of the colony, also arranged to organise Singapore into functional and ethnic subdivisions under the drafted Raffles Plan of Singapore.[11] Today, the remnants of this organisation like the Raffles Town Plan can be found in the ethnic neighbourhoods, within public housing estates or various places across Singapore.

Treaty of Friendship and Alliance

Further agreements of the Malay chiefs would gradually erode their influence and control over Singapore. In December 1822, the Malay chiefs' claim to Singapore's revenue was changed to a monthly payment. On 7 June 1823, Raffles arranged for another agreement with the Sultan and Temenggong to buy out their judicial power and rights to the lands except for the areas reserved for the Sultan and Temenggong.[22] They would give up their rights to numerous functions on the island, including the collection of port taxes, in return for lifelong monthly payments of $1500 and $800 respectively.[23] This agreement brought the island squarely under British law, with the proviso that it would take into account Malay customs, traditions and religious practices, "where they shall not be contrary to reason, justice or humanity."[22]

A further treaty, the Treaty of Friendship and Alliance, was arranged by the second Resident John Crawfurd with the Malay chiefs and signed on 2 August 1824 to replace the Singapore Treaty. Singapore, including its nearby islands, was officially fully ceded to the East India Company, and in return, the chiefs would have their debts cancelled and receive an allowance for life, with each given an additional lump sum of 20,000 Spanish dollars.[24]

After installing John Crawfurd, an efficient and frugal administrator, as the new governor, Raffles departed for Britain in October 1823.[25] He would never return to Singapore. Most of his personal possessions were lost after his ship, the Fame, caught fire and sank, and he died only a few years later, in 1826, at the age of 44.[26]

Straits Settlements

The status of Singapore as a British possession was cemented by the Anglo-Dutch Treaty of 1824, which carved up the Malay archipelago between the two colonial powers. The area north of the Straits of Malacca, including Penang, Malacca, and Singapore, was designated as the British sphere of influence, while the area south of the Straits was assigned to the Dutch.[27]

This division had far-reaching consequences for the region: modern-day Malaysia and Singapore correspond to the British area established in the treaty, and modern-day Indonesia to the Dutch. In 1826, Singapore was grouped together with Penang and Malacca into a single administrative unit, the Straits Settlements, under the British East India Company.[27]

References

- Trocki, C. (1990). Opium and empire : Chinese society in Colonial eh Singapore, 1800–1910. Ithaca, N.Y. : Cornell University Press.

- Miksic 2013, pp. 181–182.

- Paul Wheatley (1961). The Golden Khersonese: Studies in the Historical Geography of the Malay Peninsula before A.D. 1500. Kuala Lumpur: University of Malaya Press. pp. 82–85. OCLC 504030596.

- Miksic 2013, pp. 183–185.

- Miksic 2013, pp. 155–163.

- Turnbull 2009, pp. 21–22.

- "Singapore – Precolonial Era". U.S. Library of Congress. Retrieved 18 June 2006.

- "Early Names". www.sg. Archived from the original on 12 April 2010. Retrieved 1 October 2011.

- Cornelius-Takahama, Vernon (26 November 1999). "Sang Nila Utama". National Library Board, Singapore. Archived from the original on 11 May 2011. Retrieved 1 October 2011.

- Nor-Afidah Abd Rahman. "The China Trade". Singapore Infopedia. National Library Board. Archived from the original on 8 February 2017.

- "Singapore – Founding and Early Years". U.S. Library of Congress. Retrieved 18 July 2006.

- Jean E. Abshire (21 March 2011). The History of Singapore. Greenwood. pp. 37–38. ISBN 978-0313377426.

- "Raffles' landing in Singapore". Singapore Infopedia. Retrieved 6 July 2012.

- Saw Swee-Hock (30 June 2012). The Population of Singapore (3rd ed.). ISEAS Publishing. pp. 7–8. ISBN 978-9814380980.

- Turnbull, C. M. (1981). A short history of Malaysia, Singapore and Brunei (Asian ed.). Singapore: Graham Brash. p. 97. ISBN 9971947064. OCLC 10483808.

- "The 1819 Singapore Treaty". Singapore Infopedia. National Library Board.

- Jenny Ng (7 February 1997). "1819 – The February Documents". Ministry of Defence (Singapore). Archived from the original on 6 September 2006. Retrieved 18 July 2006.

- "Milestones in Singapore's Legal History". Supreme Court, Singapore. Retrieved 18 July 2006.

- Pearson, H. F. (July 1953). "Singapore from the Sea, June 1823. Notes on a Recently Discovered Sketch attributed to Lt. Phillip Jackson". Journal of the Malayan Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society. 26 (1 (161)): 43–55. JSTOR 41502903.

- Lily Zubaidah Rahim (9 November 2010). Singapore in the Malay World: Building and Breaching Regional Bridges. Taylor & Francis. p. 24. ISBN 9781134013975.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Turnbull 2009, p. 41.

- Turnbull 2009, pp. 39–41.

- Carl A. Trocki (30 November 2007). Prince of Pirates: The Temenggongs and the Development of Johor and Singapore, 1784–1885 (2nd Revised ed.). NUS Press. p. 66. ISBN 978-9971693763.

- "Treaty of Friendship and Alliance is signed". HistorySG. National Library Board.

- Bastin, John. "Malayan Portraits: John Crawfurd", in Malaya, vol.3 (December 1954), pp.697–698.

- J C M Khoo; C G Kwa; L Y Khoo (1998). "The Death of Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles (1781–1826)". Singapore Medical Journal. 39 (12): 564–5. PMID 10067403. Archived from the original on 3 September 2006. Retrieved 18 July 2006.

- "Signing of the Anglo-Dutch Treaty (Treaty of London) of 1824". HistorySG. Singapore Government. Retrieved 4 February 2018.

Bibliography

- Miksic, John N. (15 November 2013). Singapore and the Silk Road of the Sea, 1300–1800. NUS Press. ISBN 978-9971695743.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Turnbull, C.M. (30 October 2009). A History of Modern Singapore, 1819–2005. NUS Press. ISBN 978-9971694302.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)