Yijing (monk)

Yijing (635–713 CE), formerly romanized as I-ching or I-tsing,[1] was a Tang-era Chinese Buddhist monk famed as a traveller and translator. His account of his travels is an important source for the history of the medieval kingdoms along the sea route between China and India, especially Srivijaya in Indonesia. A student of the Buddhist university at Nālandā (now in Bihar, India), he was also responsible for the translation of many Buddhist texts from Sanskrit and Pali into Chinese.

Yijing | |

|---|---|

Portrait of Yijing. | |

| Born | 635 CE Fanyang (Yanjing), Tang Empire |

| Died | 713 CE |

| Occupation | Buddhist monk, traveler |

| Personal | |

| Religion | Buddhism |

| Senior posting | |

| Teacher | Shi Huen |

| Yijing | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

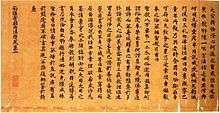

Excerpt of a scroll from Yijing's Buddhist Monastic Traditions of Southern Asia. Tenri, Nara, Japan | |||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 義淨 | ||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 义净 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Buddhist title | |||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 三藏法師義淨 | ||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 三藏法师义净 | ||||||||

| Literal meaning | Tripitaka Dharma-Master Yijing | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Zhang Wenming | |||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 張文明 | ||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 张文明 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

Journey

To Srivijaya and Nālandā

Yijing was born Zhang Wenming. He became a monk at age 14 and was an admirer of Faxian and Xuanzang, both famed monks of his childhood. Provided funding by an otherwise unknown benefactor named Fong, he decided to visit the renowned Buddhist university of Nālandā, in Bihar, India, to further study Buddhism. Traveling by a Persian boat out of Guangzhou, he arrived in Srivijaya (today's Palembang of Sumatra) after 22 days, where he spent the next six months learning Sanskrit grammar and the Malay language. He went on to record visits to the nations of Malayu and Kiteh (Kedah), and in 673 after ten days of additional travel reached the "naked kingdom" (south west of Shu). Yijing recorded his impression of the "Kunlun peoples", using an ancient Chinese word for Malay peoples. "Kunlun people have curly hair, dark bodies, bare feet and wear sarongs." He then arrived at the East coast of India, where he met a senior monk and stayed a year to study Sanskrit. Both later followed a group of merchants and visited 30 other principalities. Halfway to Nālandā, Yijing fell sick and was unable to walk; gradually he was left behind by the group. He walked to Nālandā where he stayed for 11 years.

Returning to Srivijaya

In 687, Yijing stopped in the kingdom of Srivijaya on his way back to Tang China. At that time, Palembang was a centre of Buddhism where foreign scholars gathered, and Yijing stayed there for two years to translate original Sanskrit Buddhist scriptures into Chinese. In the year 689 he returned to Guangzhou to obtain ink and papers (note: Srivijaya then had no paper and ink) and returned again to Srivijaya the same year.

Return to China

In 695, he completed all translation works and finally returned to China at Luoyang, and received a grand welcome back by Empress Wu Zetian. His total journey took 25 years. He brought back some 400 Buddhist texts translated into Chinese.[2][3] Account of Buddhism sent from the South Seas and Buddhist Monk's Pilgrimage of the Tang Dynasty are two of Yijing's best travel diaries, describing his adventurous journey to Srivijaya and India, reporting on the society of India, the lifestyles of various local peoples, and more.

Distribution of Buddhist traditions

In the great majority of areas in India, Yijing writes that there were followers of both "vehicles" (Skt. Yana), with some Buddhists practicing according to the "Hinayana" and others practicing according to the Mahayana.[4] However, he describes Northern India and most of the islands of the South Seas (i.e. Sumatra, Java, etc.) as principally "Hīnayāna." In contrast, the Buddhists in China and Malayu are described as principally following the Mahāyāna.[5]

Yijing wrote about relationship between the various "vehicles" and the early Buddhist schools in India. He wrote, "There exist in the West numerous subdivisions of the schools which have different origins, but there are only four principal schools of continuous tradition." These schools are namely the Mahāsāṃghika, Sthavira, Mulasarvastivada, and Saṃmitīya nikāyas.[6] Explaining their doctrinal affiliations, he then writes, "Which of the four schools should be grouped with the Mahāyāna or with the Hīnayāna is not determined." That is to say, there was no simple correspondence between a monastic sect and whether its members learned "Hīnayāna" or "Mahāyāna" teachings.[7]

Buddhism in Srivijaya

Yijing praised the high level of Buddhist scholarship in Srivijaya and advised Chinese monks to study there prior to making the journey to Nalanda in India.

In the fortified city of Bhoga, Buddhist priests number more than 1,000, whose minds are bent on learning and good practice. They investigate and study all the subjects that exist just as in India; the rules and ceremonies are not at all different. If a Chinese priest wishes to go to the West in order to hear and read the original scriptures, he had better stay here one or two years and practice the proper rules....

Yijing's visits to Srivijaya gave him the opportunity to meet with others who had come from other neighboring islands. According to him, the Javanese kingdom of Ho-ling was due east of the city of Bhoga at a distance that could be spanned by a four or five days' journey by sea. He also wrote that Buddhism was flourishing throughout the islands of Southeast Asia. "Many of the kings and chieftains in the islands of the Southern Sea admire and believe in Buddhism, and their hearts are set on accumulating good actions."

Translations into Chinese

Yijing translated more than 60 texts into Chinese, including:

- Mūlasarvāstivāda Vinaya (一切有部毗奈耶)

- Golden Light Sutra (金光明最勝王經) in 703

- Diamond Sutra (能斷金剛般若波羅蜜多經, T. 239) in 703

- Sūtra of the Original Vows of the Medicine Buddha of Lapis Lazuli Radiance and the Seven Past Buddhas (藥師琉璃光七佛本願功德經, T. 451), in 707

- Avadanas (譬喻經) in 710

See also

References

Citations

- Schoff, Wilfred Harvey, ed. (1912), Periplus of the Erythraean Sea, Philadelphia: Commercial Museum, p. 213.

- 南海寄歸內法傳 Account of Buddhism sent from the South Seas

- 大唐西域求法高僧傳 Buddhist Monk's Pilgrimage of the Tang Dynasty

- Yijing. Takakusu, J. (tr.) A Record of the Buddhist Religion As Practiced in India and the Malay Archipelago. 1896. p. xxv

- Yijing. Takakusu, J. (tr.) A Record of the Buddhist Religion As Practiced in India and the Malay Archipelago. 1896. p. xxv

- Walser, Joseph (2005) Nagarjuna in Context: Mahayana Buddhism and Early Indian Culture: pp. 41

- Walser, Joseph (2005) Nagarjuna in Context: Mahayana Buddhism and Early Indian Culture: pp. 41-42

Bibliography

- Dutt S, Buddhist Monks and Monasteries of India, with the translation of passages (given by Latika Lahiri to S. Dutt, see note 2 p. 311) from Yijing's book: Buddhist Pilgrim Monks of Tang Dynasty as an appendix. London, 1952

- I-Tsing, A Record of the Buddhist Religion : As Practised in India and the Malay Archipelago (A.D. 671-695), Translated by J. Takakusu, Clarendon press 1896. Reprint. New Delhi, AES, 2005, ISBN 81-206-1622-7. Internet Archive

- I-Tsing, Chinese Monks in India, Biography of Eminent Monks Who Went to the Western World in Search of the Law During the Great tang Dynasty, Translated by Latika Lahiri, Delhi, etc.: Motilal Banarsidass, 1986

- Sen, T. (2006). The Travel Records of Chinese Pilgrims Faxian, Xuanzang, and Yijing, Education About Asia 11 (3), 24-33

- Weerawardane, Prasani (2009). Journey to the West: Dusty Roads, Stormy Seas and Transcendence, biblioasia 5 (2), 14-18

- Yijing, Rongxi, Li, transl. (2000). A Record of the Inner Law Sent Home from the South Seas, Berkeley CA: Bukkyo Dendo Kyokai. ISBN 1-886439-09-5