John Quincy Adams

John Quincy Adams (/ˈkwɪnzi/ (![]()

John Quincy Adams | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

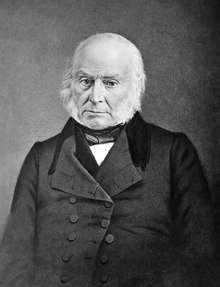

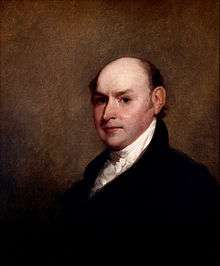

Adams in c. 1843-48, photographed by Mathew Brady | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 6th President of the United States | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office March 4, 1825 – March 4, 1829 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vice President | John C. Calhoun | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | James Monroe | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Andrew Jackson | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 8th United States Secretary of State | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office September 22, 1817 – March 3, 1825 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| President | James Monroe | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | James Monroe | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Henry Clay | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| United States senator from Massachusetts | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office March 4, 1803 – June 8, 1808 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Jonathan Mason | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | James Lloyd | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Member of the United States House of Representatives from Massachusetts | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office March 4, 1831 – February 23, 1848 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Joseph Richardson | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Horace Mann | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Constituency |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Member of Massachusetts Senate | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 1802–1803 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Personal details | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Born | July 11, 1767 Braintree, Massachusetts Bay, British America | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Died | February 23, 1848 (aged 80) Washington, D.C., U.S. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Cause of death | Stroke | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Resting place | United First Parish Church | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Political party |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Spouse(s) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Children | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Parents | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Relatives | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Education | Harvard University (AB, AM) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Signature | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

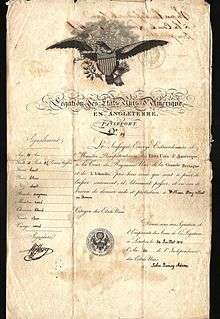

Born in what is now Quincy, Massachusetts[3] (then part of the town of Braintree), Adams spent much of his youth in Europe, where his father served as a diplomat. After returning to the United States, Adams established a successful legal practice in Boston. In 1794, President George Washington appointed Adams as the U.S. ambassador to the Netherlands, and Adams would serve in high-ranking diplomatic posts until 1801, when Thomas Jefferson took office as president. Federalist leaders in Massachusetts arranged for Adams's election to the United States Senate in 1802, but Adams broke with the Federalist Party over foreign policy and was denied re-election. In 1809, Adams was appointed as the U.S. ambassador to Russia by President James Madison, a member of the Democratic-Republican Party. Adams held diplomatic posts for the duration of Madison's presidency, and he served as part of the American delegation that negotiated an end to the War of 1812. In 1817, newly elected president James Monroe selected Adams as his Secretary of State. In that role, Adams negotiated the Adams–Onís Treaty, which provided for the American acquisition of Florida. He also helped formulate the Monroe Doctrine, which became a key tenet of U.S. foreign policy.

The 1824 presidential election was contested by Adams, Andrew Jackson, William H. Crawford, and Henry Clay, all of whom were members of the Democratic-Republican Party. As no candidate won a majority of the electoral vote, the House of Representatives held a contingent election to determine the president, and Adams won that contingent election with the support of Clay. As president, Adams called for an ambitious agenda that included federally funded infrastructure projects, the establishment of a national university, and engagement with the countries of Latin America, but many of his initiatives were defeated in Congress. During Adams's presidency, the Democratic-Republican Party polarized into two major camps: one group, known as the National Republican Party, supported President Adams, while the other group, known as the Democratic Party, was led by Andrew Jackson. The Democrats proved to be more effective political organizers than Adams and his National Republican supporters, and Jackson decisively defeated Adams in the 1828 presidential election.

Rather than retiring from public service, Adams won election to the House of Representatives, where he would serve from 1831 to his death in 1848. He joined the Anti-Masonic Party in the early 1830s before becoming a member of the Whig Party, which united those opposed to President Jackson. During his time in Congress, Adams became increasingly critical of slavery and of the Southern leaders whom he believed controlled the Democratic Party. He was particularly opposed to the annexation of Texas and the Mexican–American War, which he saw as a war to extend slavery. He also led the repeal of the "gag rule", which had prevented the House of Representatives from debating petitions to abolish slavery. Historians generally concur that Adams was one of the greatest diplomats and secretaries of state in American history. They typically rank him as a mediocre president who had an ambitious agenda but could not get it passed by Congress.

Early life, education, and early career

John Quincy Adams was born on July 11, 1767, to John and Abigail Adams (née Smith) in a part of Braintree, Massachusetts that is now Quincy.[4] He was named for his mother's maternal grandfather, Colonel John Quincy, after whom Quincy, Massachusetts, is named.[5] Young Adams was educated by private tutors – his cousin James Thaxter and his father's law clerk, Nathan Rice.[6] He soon began to exhibit his literary skills, and in 1779 he initiated a diary which he kept until just before he died in 1848.[7] Until the age of ten, Adams grew up on the family farm in Braintree, largely in the care of his mother. Though frequently absent due to his participation in the American Revolution, John Adams maintained a correspondence with his son, encouraging him to read works by authors such as Thucydides and Hugo Grotius.[8] With his father's encouragement, Adams would also translate classical authors such as Virgil, Horace, Plutarch, and Aristotle.[9]

In 1778, Adams and his father departed for Europe, where John Adams would serve as part of American diplomatic missions in France and the Netherlands.[10] During this period, Adams studied French, Greek, and Latin, and attended several schools, including Leiden University.[11] In 1781, Adams traveled to Saint Petersburg, Russia, where he served as the secretary of American diplomat Francis Dana.[12] He returned to the Netherlands in 1783, and accompanied his father to Great Britain in 1784.[13] Though Adams enjoyed Europe, he and his family decided he needed to return to the United States to complete his education and eventually launch a political career.[14]

Adams returned to the United States in 1785 and earned admission as a member of the junior class of Harvard College the following year. He was elected to Phi Beta Kappa and excelled academically, graduating second in his class in 1787.[15] After graduating from Harvard, he studied law with Theophilus Parsons in Newburyport, Massachusetts, from 1787 to 1789.[16] Adams initially opposed the ratification of the United States Constitution, but he ultimately came to accept the document, and in 1789 his father was elected as the first Vice President of the United States.[17] In 1790, Adams opened his own legal practice in Boston. Despite some early struggles, he was successful as an attorney and established financial independence from his parents.[18]

Early political career (1793–1817)

Early diplomatic career and marriage

Adams initially avoided becoming directly involved in politics, instead focusing on building his legal career. In 1791, he wrote a series of pseudonymously published essays arguing that Britain provided a better governmental model than France. Two years later, he published another series of essays attacking Edmond-Charles Genêt, a French diplomat who sought to undermine President George Washington's policy of neutrality in the French Revolutionary Wars.[19] In 1794, Washington appointed Adams as the U.S. ambassador to the Netherlands; Adams considered declining the role but ultimately took the position at the advice of his father.[20] While abroad, Adams continued to urge neutrality, arguing that the United States would benefit economically by staying out of the ongoing French Revolutionary Wars.[21] His chief duty as the ambassador to the Netherlands was to secure and maintain loans essential to U.S. finances. On his way to the Netherlands, he met with John Jay, who was then negotiating the Jay Treaty with Great Britain. Adams supported the Jay Treaty, but it proved unpopular with many in the United States, contributing to a growing partisan split between the Federalist Party of Alexander Hamilton and the Democratic-Republican Party of Thomas Jefferson.[22]

Adams spent the winter of 1795–96 in London, where he met Louisa Catherine Johnson, the second daughter of American merchant Joshua Johnson. In April 1796, Louisa accepted Adams's proposal of marriage. Adams's parents disapproved of his decision to marry a woman who had grown up in England, but he informed his parents that he would not reconsider his decision.[23] Adams initially wanted to delay his wedding to Louisa until he returned to the United States, but they were married in All Hallows-by-the-Tower in July 1797.[24][lower-alpha 2] Shortly after the wedding, Joshua Johnson fled England to escape his creditors, and Adams did not receive the dowry that Johnson had promised him, much to the embarrassment of Louisa. Nonetheless, Adams noted in his own diary that he had no regrets about his decision to marry Louisa.[26]

In 1796, Washington appointed Adams as the U.S. ambassador to Portugal.[27] Later in that same year, John Adams defeated Jefferson in the 1796 presidential election. When the elder Adams became president, he appointed his son as the U.S. ambassador to Prussia.[28] Though concerned that his appointment would be criticized as nepotistic, Adams accepted the position and traveled to the Prussian capital of Berlin with his wife and his younger brother, Thomas Boylston Adams. The State Department charged Adams with developing commercial relations with Prussia and Sweden, but President Adams also asked his son to write him frequently about affairs in Europe.[29] In 1799, Adams negotiated a new trade agreement between the United States and Prussia, though he was never able to complete an agreement with Sweden.[30] He frequently wrote to family members in the United States, and in 1801 his letters about the Prussian region of Silesia were published in a book titled Letters on Silesia.[31] In the 1800 presidential election, Jefferson defeated John Adams, and both Adams and his son left office in early 1801.[32]

U.S. Senator from Massachusetts

On his return to the United States, Adams re-established a legal practice in Boston, and in April 1802 he was elected to the Massachusetts Senate.[33] In November of that same year he ran unsuccessfully for the United States House of Representatives.[34] In February 1803, the Massachusetts legislature elected Adams to the United States Senate. Though somewhat reluctant to affiliate with any political party, Adams joined the Federalist minority in Congress.[35] Like his Federalist colleagues, he opposed the impeachment of Associate Justice Samuel Chase, an outspoken supporter of the Federalist Party.[36]

Adams had strongly opposed Jefferson's 1800 presidential candidacy, but he gradually became alienated from the Federalist Party. His disaffection was driven by the party's declining popularity, disagreements over foreign policy, and Adams's hostility to Timothy Pickering, a Federalist Party leader whom Adams viewed as overly favorable to Britain. Unlike other New England Federalists, Adams supported the Jefferson administration's Louisiana Purchase and generally favored expansionist policies.[37] Adams was the lone Federalist in Congress to vote for the Non-importation Act of 1806, which was designed to punish Britain for its attacks on American shipping during the ongoing Napoleonic Wars. Adams became increasingly frustrated with the unwillingness of other Federalists to condemn British actions, including impressment, and he moved closer to the Jefferson administration. After Adams supported the Embargo Act of 1807, the Federalist-controlled Massachusetts legislature elected Adams's successor several months before the end of his term and Adams resigned from the Senate shortly thereafter.[38]

While a member of the Senate, Adams served as a professor of logic at Brown University[39] and as the Boylston Professor of Rhetoric and Oratory at Harvard University. Adams's devotion to classical rhetoric shaped his response to public issues, and he would remain inspired by those rhetorical ideals long after the neo-classicalism and deferential politics of the founding generation were eclipsed by the commercial ethos and mass democracy of the Jacksonian Era. Many of Adams's idiosyncratic positions were rooted in his abiding devotion to the Ciceronian ideal of the citizen-orator "speaking well" to promote the welfare of the polis.[40] He was also influenced by the classical republican ideal of civic eloquence espoused by British philosopher David Hume.[41] Adams adapted these classical republican ideals of public oratory to the American debate, viewing its multilevel political structure as ripe for "the renaissance of Demosthenic eloquence." His Lectures on Rhetoric and Oratory (1810) looks at the fate of ancient oratory, the necessity of liberty for it to flourish, and its importance as a unifying element for a new nation of diverse cultures and beliefs. Just as civic eloquence failed to gain popularity in Britain, in the United States interest faded in the second decade of the 19th century, as the "public spheres of heated oratory" disappeared in favor of the private sphere.[42]

Minister to Russia

After resigning from the Senate, Adams was ostracized by Massachusetts Federalist leaders, but he declined Democratic-Republican entreaties to seek office.[43] In 1809, he argued before the Supreme Court of the United States in the case of Fletcher v. Peck, and the Supreme Court ultimately agreed with Adams's argument that the Constitution's Contract Clause prevented the state of Georgia from invalidating a land sale to out-of-state companies.[44] Later that year, President James Madison appointed Adams as the first United States Minister to Russia in 1809. Though Adams had only recently broken with the Federalist Party, his support of Jefferson's foreign policy had earned him goodwill with the Madison Administration.[45] Adams was well-qualified for the role after his experiences in Europe generally and Russia specifically.[46]

After a difficult passage through the Baltic Sea, Adams arrived in the Russian capital of St. Petersburg in October 1809. He quickly established a productive working relationship with Russian official Nikolay Rumyantsev and eventually befriended Tsar Alexander I of Russia. Adams continued to favor American neutrality between France and Britain during the Napoleonic War.[47] Louisa was initially distraught at the prospect of living in Russia, but she became a popular figure at the Russian court.[48] From his diplomatic post, Adams observed the French Emperor Napoleon's invasion of Russia, which ended in defeat for the French.[49] In February 1811, Adams was nominated by President Madison as an Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court.[50] The nomination was unanimously confirmed by the Senate, but Adams declined the seat, preferring a career in politics and diplomacy, so Joseph Story took the seat instead.[51]

Treaty of Ghent and ambassador to Britain

Adams had long feared that the United States would enter a war it could not win against Britain, and by early 1812 he saw such a war as inevitable due to the constant British attacks on American shipping and the British practice of impressment. In mid-1812, the United States declared war against Britain, beginning the War of 1812. Tsar Alexander attempted to mediate the conflict between Britain and the United States, and President Madison appointed Adams, Secretary of the Treasury Albert Gallatin, and Federalist Senator James A. Bayard to a delegation charged with negotiating an end to the war. Gallatin and Bayard arrived in St. Petersburg in July 1813, but the British declined Tsar Alexander's offer of mediation. Hoping to commence the negotiations at another venue, Adams left Russia in April 1814.[52] Negotiations finally began in mid-1814 in Ghent, where Adams, Gallatin, and Bayard were joined by two additional American delegates, Jonathan Russell and former Speaker of the House Henry Clay.[53] Adams, the nominal head of the delegation, got along well with Gallatin, Bayard, and Russell, but he occasionally clashed with Clay.[54]

The British delegation initially treated the United States as a defeated power, demanding the creation of an Indian barrier state from American territory near the Great Lakes. The American delegation unanimously rejected this offer, and their negotiating position was bolstered by the American victory in the Battle of Plattsburgh.[55] By November 1814, the government of Lord Liverpool decided to seek an end to hostilities with the U.S. on the basis of status quo ante bellum. Adams and his fellow commissioners had hoped for similar terms, even though a return to the status quo would mean the continuation of British practice of impressment. The treaty was signed on December 24, 1814. The United States did not gain any concessions from the treaty but could boast that it had survived a war against the strongest power in the world. Following the signing of the treaty, Adams traveled to Paris, where he witnessed first-hand the Hundred Days of Napoleon's restoration.[56]

In May 1815, Adams learned that President Madison had appointed him as the U.S. ambassador to Britain.[57] With the aid of Clay and Gallatin, Adams negotiated a limited trade agreement with Britain. Following the conclusion of the trade agreement, much of Adams's time as ambassador was spent helping stranded American sailors and prisoners of war.[58] In pursuit of national unity, newly elected president James Monroe decided a Northerner would be optimal for the position of Secretary of State, and he chose the respected and experienced Adams for the role.[59] Having spent several years in Europe, Adams returned to the United States in August 1817.[58]

Secretary of State (1817–1825)

Adams served as Secretary of State throughout Monroe's eight-year presidency, from 1817 to 1825. Many of his successes as secretary, such as the convention of 1818 with Great Britain, the Transcontinental Treaty with Spain, and the Monroe Doctrine, were not preplanned strategy but responses to unexpected events. Adams wanted to delay American recognition of the newly independent republics of Latin America to avoid the risk of war with Spain and its European allies. However, Andrew Jackson's military campaign in Florida, and Henry Clay's threats in Congress, forced Spain to cut a deal, which Adams negotiated successfully. Biographer James Lewis says, "He managed to play the cards that he had been dealt – cards that he very clearly had not wanted – in ways that forced the Spanish cabinet to recognize the weakness of its own hand." [60] Apart from the Monroe doctrine, his last four years the Secretary of State were less successful, since he was absorbed in his presidential campaign and refused to make compromises with other nations that might have weakened his candidacy; The result was a small-scale trade war, but a successful election to the White House.

Taking office in the aftermath of the War of 1812, Adams thought that the country had been fortunate in avoiding territorial losses, and he prioritized avoiding another war with a European power, particularly Britain.[61] He also sought to avoid exacerbating sectional tensions, which had been a major issue for the country during the War of 1812.[62][lower-alpha 3] One of the major challenges confronting Adams was how to respond to the power vacuum in Latin America that arose from Spain's weakness following the Peninsular War.[64] In addition to his foreign policy role, Adams held several domestic duties, including overseeing the 1820 Census.[65]

Monroe and Adams agreed on most of the major foreign policy issues: both favored neutrality in the Latin American wars of independence, peace with Great Britain, denial of a trade agreement with the French, and expansion, peacefully if possible, into the North American territories of the Spanish Empire.[66] The president and his secretary of state developed a strong working relationship, and while Adams often influenced Monroe's policies, he respected that Monroe made the final decisions on major issues.[67] Monroe met regularly with his five-person cabinet, which initially consisted of Adams, Secretary of the Treasury William H. Crawford, Secretary of War John C. Calhoun, Secretary of the Navy Benjamin Crowninshield, and Attorney General William Wirt.[68] Adams developed a strong respect for Calhoun but believed that Crawford was unduly focused on succeeding Monroe in 1824.[69]

During his time as ambassador to Britain, Adams had begun negotiations over several contentious issues that had not been solved by the War of 1812 or the Treaty of Ghent. In 1817, the two countries agreed to the Rush–Bagot Treaty, which limited naval armaments on the Great Lakes. Negotiations between the two powers continued, resulting in the Treaty of 1818, which defined the Canada–United States border west of the Great Lakes. The boundary was set at the 49th parallel to the Rocky Mountains, while the territory to the west of the mountains, known as Oregon Country, would be jointly occupied. The agreement represented a turning point in United Kingdom–United States relations, as the U.S. turned its attention to its southern and western borders and British fears over American expansionism waned.[70]

Adams–Onís Treaty

When Adams took office, Spanish possessions bordered the United States to the South and West. In the South, Spain retained control of Florida, which the U.S. had long sought to purchase. Spain struggled to control the Indian tribes active in Florida, and some of those tribes raided U.S. territory. In the West, New Spain bordered the territory acquired by the U.S. in the Louisiana Purchase, but no clear boundary had been established between U.S. and Spanish territory.[61] After taking office, Adams began negotiations with Luis de Onís, the Spanish minister to the United States, for the purchase of Florida and the settlement of a border between the U.S. and New Spain. The negotiations were interrupted by an escalation of the Seminole War, and in December 1818 Monroe ordered General Andrew Jackson to enter Florida and retaliate against Seminoles that had raided Georgia. Exceeding his orders, Jackson captured the Spanish outposts of St. Marks and Pensacola and executed two Englishmen. While the rest of the cabinet was outraged by Jackson's actions, Adams defended them as necessary to the country's self-defense, and he eventually convinced Monroe and most of the cabinet to support Jackson.[71] Adams informed Spain that Jackson had been compelled to act by Spain's failure to police its own territory, and he advised Spain to either secure the region or sell it to the United States.[72] The British, meanwhile, declined to risk their recent rapprochement with the United States, and did not make a major diplomatic issue out of Jackson's execution of two British nationals.[73]

Negotiations between Spain and the United States continued, and Spain agreed to cede Florida. The determination of the western boundary of the United States proved more difficult. American expansionists favored setting the border at the Rio Grande, but Spain, intent on protecting its colony of Mexico from American encroachment, insisted on setting the boundary at the Sabine River. At Monroe's direction, Adams agreed to the Sabine River boundary, but he insisted that Spain cede its claims on Oregon Country.[74] Adams was deeply interested in establishing American control over the Oregon Country, partly because he believed that control of that region would spur trade with Asia. The acquisition of Spanish claims to the Pacific Northwest also allowed the Monroe administration to pair the acquisition of Florida, which was chiefly sought by Southerners, with territorial gains favored primarily by those in the North.[75] After extended negotiations, Spain and the United States agreed to the Adams–Onís Treaty, which was ratified in February 1821.[71] Adams was deeply proud of the treaty, though he privately was concerned by the potential expansion of slavery into the newly acquired territories.[76] In 1824, the Monroe administration would further bolster U.S. claims to Oregon by reaching the Russo-American Treaty of 1824, which set the southern border of Russian Alaska at the parallel 54°40′ north.[77]

Monroe Doctrine

As the Spanish Empire continued to fracture during Monroe's second term, Adams and Monroe became increasingly concerned that the "Holy Alliance" of Prussia, Austria, and Russia would seek to bring Spain's erstwhile colonies under their control. In 1822, following the conclusion of the Adams–Onís Treaty, the Monroe administration recognized the independence of several Latin American countries, including Argentina and Mexico. In 1823, British Foreign Secretary George Canning suggested that the U.S. and Britain should work together to preserve the independence of these fledgling republics. The cabinet debated whether to accept the offer, but Adams opposed it. Instead, Adams urged Monroe to publicly declare U.S. opposition to any European attempt to colonize or re-take control of territory in the Americas, while also committing the U.S. to neutrality in European affairs. In his December 1823 annual message to Congress, Monroe laid out the Monroe Doctrine, which was largely built upon Adams's ideas.[78] In issuing the Monroe Doctrine, the United States displayed a new level of assertiveness in international relations, as the doctrine represented the country's first claim to a sphere of influence. It also marked the country's shift in psychological orientation away from Europe and towards the Americas. Debates over foreign policy would no longer center on relations with Britain and France, but would instead focus on western expansion and relations with Native Americans.[79] The doctrine became one of the foundational principles of U.S. foreign policy.[78]

1824 presidential election

Immediately upon becoming Secretary of State, Adams emerged as one of Monroe's most likely successors, as the last three presidents had all served in the role at some point before taking office. As the 1824 election approached, Henry Clay, John C. Calhoun (who later dropped out of the race), and William H. Crawford appeared to be Adams's primary competition to succeed Monroe.[80] Crawford favored state sovereignty and a strict constructionist view of the Constitution, while Clay, Calhoun, and Adams embraced federally funded internal improvements, high tariffs, and the Second Bank of the United States, which was also known as the national bank.[81] Because the Federalist Party had all but collapsed after the War of 1812, all the major presidential candidates were members of the Democratic-Republican Party.[82] Adams felt that his own election as president would vindicate his father, while also allowing him to pursue an ambitious domestic policy. Though he lacked the charisma of his competitors, Adams was widely respected and benefited from the lack of other prominent Northern political leaders.[83]

Adams's top choice for the role of vice president was General Andrew Jackson; Adams noted that "the Vice-Presidency was a station in which [Jackson] could hang no one, and in which he would need to quarrel with no one."[84] However, as the 1824 election approached, Jackson jumped into the race for president.[82] While the other candidates based their candidacies on their long tenure as congressmen, ambassadors, or members of the cabinet, Jackson's appeal rested on his military service, especially in the Battle of New Orleans.[85] The congressional nominating caucus had decided upon previous Democratic-Republican presidential nominees, but it had become largely discredited by 1824. Candidates were instead nominated by state legislatures or nominating conventions, and Adams received the endorsement of the New England legislatures.[86] The regional strength of each candidate played an important role in the election; Adams was popular in New England, Clay and Jackson were strong in the West, and Jackson and Crawford competed for the South.[87]

| 1825 contingent presidential election vote distribution | ||

|---|---|---|

| States for Adams | States for Jackson | States for Crawford |

|

|

|

| Total: 13 (54%) | Total: 7 (29%) | Total: 4 (17%) |

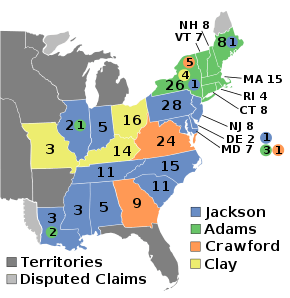

In the 1824 presidential election, Jackson won a plurality in the Electoral College, taking 99 of the 261 electoral votes, while Adams won 84, Crawford won 41, and Clay took 37. Calhoun, meanwhile, won a majority of the electoral votes for vice president.[87] Adams nearly swept the electoral votes of New England and won a majority of the electoral votes in New York, but he won a total of just six electoral votes from the slave states. Most of Jackson's support came from slave-holding states, but he also won New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and some electoral votes from the Northwest.[88] As no candidate won a majority of the electoral votes, the House was required to hold a contingent election under the terms of the Twelfth Amendment. The House would decide among the top three electoral vote winners, with each state's delegation having one vote; thus, unlike his three rivals, Clay was not eligible to be elected by the House.[87]

Adams knew that his own victory in the contingent election would require the support of Clay, who wielded immense influence in the House of Representatives.[89] Though they were quite different in temperament and had clashed in the past, Adams and Clay shared similar views on national issues. By contrast, Clay viewed Jackson as a dangerous demagogue, and he was unwilling to support Crawford due to the latter's health issues.[90] Adams and Clay met before the contingent election, and Clay agreed to support Adams in the election.[91] Adams also met with Federalists such as Daniel Webster, promising that he would not deny governmental positions to members of their party.[92] On February 9, 1825, Adams won the contingent election on the first ballot, taking 13 of the 24 state delegations. Adams won the House delegations of all the states in which he or Clay had won a majority of the electoral votes, as well as the delegations of Illinois, Louisiana, and Maryland.[91] Adams's victory made him the first child of a president to serve as president himself.[lower-alpha 4] After the election, many of Jackson's supporters claimed that Adams and Clay had reached a "Corrupt Bargain" whereby Adams promised Clay the position of Secretary of State in return for Clay's support.[91]

Presidency (1825–1829)

Inauguration

Adams was inaugurated on March 4, 1825. He took the oath of office on a book of constitutional law, instead of the more traditional Bible.[93] In his inaugural address, he adopted a post-partisan tone, promising that he would avoid party-building and politically motivated appointments. He also proposed an elaborate program of "internal improvements": roads, ports, and canals. Though some worried about the constitutionality of such federal projects, Adams argued that the General Welfare Clause provided for broad constitutional authority. He promised that he would ask Congress to authorize many such projects.[94]

Administration

| The Adams Cabinet | ||

|---|---|---|

| Office | Name | Term |

| President | John Quincy Adams | 1825–1829 |

| Vice President | John C. Calhoun | 1825–1829 |

| Secretary of State | Henry Clay | 1825–1829 |

| Secretary of the Treasury | Richard Rush | 1825–1829 |

| Secretary of War | James Barbour | 1825–1828 |

| Peter B. Porter | 1828–1829 | |

| Attorney General | William Wirt | 1825–1829 |

| Secretary of the Navy | Samuel L. Southard | 1825–1829 |

Adams presided over a harmonious and productive cabinet that he met with on a weekly basis.[95] Like Monroe, Adams sought a geographically balanced cabinet that would represent the various party factions, and he asked the members of the Monroe cabinet to remain in place for his own administration.[96] Samuel L. Southard of New Jersey stayed on as Secretary of the Navy, William Wirt kept his post of Attorney General,[97] and John McLean of Ohio continued to serve as the Postmaster General, an important position that was not part of the cabinet.[98] Adams's first choices for Secretary of War and Secretary of the Treasury were Andrew Jackson and William Crawford, but each declined to serve in the administration. Adams instead selected James Barbour of Virginia, a prominent supporter of Crawford, to lead the War Department. Leadership of the Treasury Department went to Richard Rush of Pennsylvania, who would become a prominent advocate of internal improvements and protective tariffs within the administration.[99] Adams chose Henry Clay as Secretary of State, angering those who believed that Clay had offered his support in the 1824 election for the most prestigious position in the cabinet.[100] Though Clay would later regret accepting the position since it reinforced the "Corrupt Bargain" accusation, Clay's strength in the West and interest in foreign policy made him a natural choice for the top cabinet position.[101]

Domestic affairs

Ambitious agenda

In his 1825 annual message to Congress,[102] Adams presented a comprehensive and ambitious agenda. He called for major investments in internal improvements as well as the creation of a national university, a naval academy, and a national astronomical observatory. Noting the healthy status of the treasury and the possibility for more revenue via land sales, Adams argued for the completion of several projects that were in various stages of construction or planning, including a road from Washington to New Orleans.[103] He also proposed the establishment of a Department of the Interior as a new cabinet-level department that would preside over these internal improvements.[104] Adams hoped to fund these measures primarily through Western land sales, rather than increased taxes or public debt.[81] The domestic agenda of Adams and Clay, which would come to be known as the American System, was designed to unite disparate regional interests in the promotion of a thriving national economy.[105]

Adams's programs faced opposition from various quarters. Many disagreed with his broad interpretation of the constitution and preferred that power be concentrated in state governments rather than the federal government. Others disliked interference from any level of government and were opposed to central planning.[106] Some in the South feared that Adams was secretly an abolitionist and that he sought to subordinate the states to the federal government.[107] Most of the president's proposals were defeated in Congress. Adams's ideas for a national university, national observatory, and the establishment of a uniform system of weights and measures never received congressional votes.[108] His proposal for the creation of a naval academy won the approval of the Senate, but was defeated in the House; opponents objected to the naval academy's cost and worried that the establishment of such an institution would "produce degeneracy and corruption of the public morality."[109] Adams's proposal to establish a national bankruptcy law was also defeated.[108]

Unlike other aspects of his domestic agenda, Adams won congressional approval for several ambitious infrastructure projects.[110] Between 1824 and 1828, the United States Army Corps of Engineers conducted surveys for a bevy of potential roads, canals, railroads, and improvements in river navigation. Adams presided over major repairs and further construction on the National Road, and shortly after he left office the National Road extended from Cumberland, Maryland, to Zanesville, Ohio.[111] The Adams administration also saw the beginning of the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal; the construction of the Chesapeake and Delaware Canal and the Louisville and Portland Canal around the falls of the Ohio; the connection of the Great Lakes to the Ohio River system in Ohio and Indiana; and the enlargement and rebuilding of the Dismal Swamp Canal in North Carolina.[112] Additionally, the first passenger railroad in the United States, the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, was constructed during Adams's presidency. Though many of these projects were undertaken by private actors, the government often provided money or land to aid the completion of such projects.[113]

Formation of political parties

In the immediate aftermath of the 1825 contingent election, Jackson was gracious to Adams.[114] Nevertheless, Adams's appointment of Clay rankled Jackson, who received a flood of letters encouraging him to run. In 1825, Jackson accepted the presidential nomination of the Tennessee legislature for the 1828 election.[115] Though he had been close with Adams during Monroe's presidency, Vice President Calhoun was also politically alienated from the president by the appointment of Clay, since that appointment established Clay as the natural heir to Adams.[116] Adams's ambitious December 1825 annual message to Congress further galvanized the opposition, with important figures such as Francis Preston Blair of Kentucky and Thomas Hart Benton of Missouri breaking with the Adams administration.[117] By the end of the first session of the 19th United States Congress, an anti-Adams congressional coalition consisting of Jacksonians (led by Benton and Hugh Lawson White), Crawfordites (led by Martin Van Buren and Nathaniel Macon), and Calhounites (led by Robert Y. Hayne and George McDuffie) had emerged.[118] Aside from Clay, Adams lacked strong supporters outside of the North, and Edward Everett, John Taylor, and Daniel Webster served as his strongest advocates in Congress.[119] Supporters of Adams began calling themselves National Republicans, while supporters of Jackson began calling themselves Democrats.[120] In the press, they were often described as "Adams Men" and "Jackson Men."[121]

In the 1826 elections, Adams's opponents picked up seats throughout the country, as allies of Adams failed to coordinate among themselves.[122] Pro-Adams Speaker of the House John Taylor was replaced by Andrew Stevenson, a Jackson supporter;[123] as Adams himself noted, the U.S. had never seen a Congress that was firmly under the control of political opponents of the president.[124] After the elections, Van Buren and Calhoun agreed to throw their support behind Jackson in 1828, with Van Buren bringing along many of Crawford's supporters.[125] Though Jackson did not articulate a detailed political platform in the same way that Adams did, his coalition was united in opposition to Adams's reliance on government planning.[126] Adams, meanwhile, clung to the hope of a non-partisan nation, and he refused to make full use of the power of patronage to build up his own party structure.[127]

Tariff of 1828

During the first half of his administration, Adams avoided taking a strong stand on tariffs, partly because he wanted to avoid alienating his allies in the South and New England.[128] After Jacksonians took power in 1827, they devised a tariff bill designed to appeal to Western states while instituting high rates on imported materials important to the economy of New England. It is unclear whether Van Buren, who shepherded the bill through Congress, meant for the bill to pass, or if he had deliberately designed it to force Adams and his allies to oppose it.[129] Regardless, Adams signed the Tariff of 1828, which became known as the "Tariff of Abominations" by opponents. Adams was denounced in the South, and he received little credit for the tariff in the North.[130]

Indian policy

Adams sought the gradual assimilation of Native Americans via consensual agreements, a priority shared by few whites in the 1820s. Yet Adams was also deeply committed to the westward expansion of the United States. Settlers on the frontier, constantly seeking to move westward, cried for a more expansionist policy that disregarded the concerns of Native Americans. Early in his term, Adams suspended the Treaty of Indian Springs after learning that the Governor of Georgia, George Troup, had forced the treaty on the Muscogee.[131] Adams signed a new treaty with the Muscogee in January 1826 that allowed the Muscogee to stay but ceded most of their land to Georgia. Troup refused to accept its terms, and authorized all Georgian citizens to evict the Muscogee.[132] A showdown between Georgia and the federal government was only averted after the Muscogee agreed to a third treaty.[133] Though many saw Troup as unreasonable in his dealings with the federal government and the Native Americans, the administration's handling of the incident alienated those in the Deep South who favored immediate Indian removal.[134]

Foreign affairs

Trade and claims

One of the major foreign policy goals of the Adams administration was the expansion of American trade.[135] His administration reached reciprocity treaties with a number of nations, including Denmark, the Hanseatic League, the Scandinavian countries, Prussia, and the Federal Republic of Central America. The administration also reached commercial agreements with the Kingdom of Hawaii and the Kingdom of Tahiti.[136] Agreements with Denmark and Sweden opened their colonies to American trade, but Adams was especially focused on opening trade with the British West Indies. The United States had reached a commercial agreement with Britain in 1815, but that agreement excluded British possessions in the Western Hemisphere. In response to U.S. pressure, the British had begun to allow a limited amount of American imports to the West Indies in 1823, but U.S. leaders continued to seek an end to Britain's protective Imperial Preference system.[137] In 1825, Britain banned U.S. trade with the British West Indies, dealing a blow to Adams's prestige.[138] The Adams administration negotiated extensively with the British to lift this ban, but the two sides were unable to come to an agreement.[139] Despite the loss of trade with the British West Indies, the other commercial agreements secured by Adams helped expand the overall volume of U.S. exports.[140]

Latin America

Aside from an unsuccessful attempt to purchase Texas from Mexico, President Adams did not seek to expand into Latin America or North America.[141] Adams and Clay instead sought engagement with Latin America to prevent it from falling under the British Empire's economic influence.[142] As part of this goal, the administration favored sending a U.S. delegation to the Congress of Panama, an 1826 conference of New World republics organized by Simón Bolívar.[143] Clay and Adams hoped that the conference would inaugurate a "Good Neighborhood Policy" among the independent states of the Americas.[144] However, the funding for a delegation and the confirmation of delegation nominees became entangled in a political battle over Adams's domestic policies, with opponents such as Van Buren impeding the process of confirming a delegation.[106] Van Buren saw the Panama Congress as an unwelcome deviation from the more isolationist foreign policy established by President Washington,[144] while many Southerners opposed involvement with any conference attended by delegates of Haiti, a republic that had been established through a slave revolt.[145] Though the U.S. delegation finally won confirmation from the Senate, it never reached the Congress of Panama due to the Senate's delay.[146]

1828 presidential election

The Jacksonians formed an effective party apparatus that adopted many modern campaign techniques. Rather than focusing on issues, they emphasized Jackson's popularity and the supposed corruption of Adams and the federal government. Jackson himself described the campaign as a "struggle between the virtue of the people and executive patronage."[147] Adams, meanwhile, refused to adapt to the new reality of political campaigns, and he avoided public functions and refused to invest in pro-administration tools such as newspapers.[148] In early 1827, Jackson was publicly accused of having encouraged his wife, Rachel, to desert her first husband.[149] In response, followers of Jackson attacked Adams's personal life, and the campaign turned increasingly nasty.[150] The Jacksonian press portrayed Adams as an out-of-touch elitist,[151] while pro-Adams newspapers attacked Jackson's past involvement in various duels and scuffles, portraying him as too emotional and impetuous for the presidency. Though Adams and Clay had hoped that the campaign would focus on the American System, it was instead dominated by the personalities of Jackson and Adams.[152]

Vice President Calhoun joined Jackson's ticket, while Adams turned to Secretary of the Treasury Richard Rush as his running mate.[153] The 1828 election thus marked the first time in U.S. history that a presidential ticket composed of two Northerners faced off against a presidential ticket composed of two Southerners.[154] In the election, Jackson won 178 of the 261 electoral votes and just under 56 percent of the popular vote.[155] Jackson won 50.3 percent of the popular vote in the free states, but 72.6 percent of the vote in the slave states.[156] No future presidential candidate would match Jackson's proportion of the popular vote until Theodore Roosevelt's 1904 campaign, while Adams's loss made him the second one-term president, after his own father.[155] By 1828, only two states did not hold a popular vote for president, and the number of votes in the 1828 election was triple that in the 1824 election. This increase in votes was due not only to the recent wave of democratization, but also because of increased interest in elections and the growing ability of the parties to mobilize voters.[157]

Later congressional career (1830–1848)

Jackson administration, 1830–1836

Adams considered permanently retiring from public life after his 1828 defeat, and he was deeply hurt by the suicide of his son, George Washington Adams, in 1829.[158] He was appalled by many of the Jackson administration's actions, including its embrace of the spoils system.[159] Though they had once maintained a cordial relationship, Adams and Jackson each came to loathe the other in the decades after the 1828 election.[160] Adams grew bored of his retirement and still felt that his career was unfinished, so he ran for and won a seat in the United States House of Representatives in the 1830 elections.[161] His election went against the generally held opinion, shared by his own wife and youngest son, that former presidents should not run for public office.[162] Nonetheless, he would win election to nine terms, serving from 1831 until his death in 1848.[1] Adams and Andrew Johnson are the only former presidents to serve in Congress.[163] After winning election, Adams became affiliated with the Anti-Masonic Party, partly because the National Republican Party's leadership in Massachusetts included many of the former Federalists that Adams had clashed with earlier in his career. The Anti-Masonic Party originated as a movement against Freemasonry, but it developed into the country's first third party and embraced a general program of anti-elitism.[164]

Adams expected a light workload when he returned to Washington at 64 years old, but Speaker Andrew Stevenson selected Adams chairman of the Committee on Commerce and Manufactures.[165] Though he identified as a member of the Anti-Masonic Party, Congress was broadly polarized into allies of Jackson and opponents of Jackson, and Adams generally aligned with the latter camp.[166] Stevenson, an ally of Jackson, expected that the committee chairmanship would keep Adams busy defending the tariff even while the Jacksonian majority on the committee would prevent Adams from accruing any real power.[167] As chairman of the committee charged with writing tariff laws, Adams became an important player in the Nullification Crisis, which stemmed largely from Southern objections to the high rates imposed by the Tariff of 1828. South Carolina leaders argued that states could nullify federal laws, and they announced that the federal government would be barred from enforcing the tariff in their state.[168] Adams helped pass the Tariff of 1832, which lowered rates, but not enough to mollify the South Carolina nullifiers. The crisis was ended when Clay and Calhoun agreed to another tariff bill, the Tariff of 1833, that furthered lower tariff rates. Adams was appalled by the Nullification Crisis's outcome, as he felt that the Southern states had unfairly benefited from challenging federal law.[169] After the crisis, Adams increasingly came to believe that Southerners exercised an undue degree of influence over the federal government, largely through their control of Jackson's Democratic Party.[170]

The Anti-Masonic Party nominated Adams in the 1833 Massachusetts gubernatorial election in a four-way race between Adams, the National Republican candidate, the Democratic candidate, and a candidate of the Working Men's Party. The National Republican candidate, John Davis, won 40% of the vote, while Adams finished in second place with 29%. Because no candidate won a majority of the vote, the state legislature decided the election. Rather than seek election by the legislature, Adams withdrew his name from contention, and the legislature selected Davis.[171] Adams was nearly elected to the Senate in 1835 by a coalition of Anti-Masons and National Republicans, but his support for Jackson in a minor foreign policy matter annoyed National Republican leaders enough that they dropped their support for his candidacy.[172] After 1835, Adams never again sought higher office, focusing instead on his service in the House of Representatives.[173]

Van Buren and Tyler administrations, 1837–1843

In the mid-1830s, the Anti-Masonic Party, the National Republicans, and other groups opposed to Jackson coalesced into the Whig Party.[174] In the 1836 presidential election Democrats put forward Martin Van Buren, while the Whigs fielded multiple presidential candidates. Because he disdained all the major party contenders for president, Adams did not take part in the campaign; Van Buren won the election.[175] Nonetheless, Adams became aligned with the Whig Party in Congress.[176] Adams generally opposed the initiatives of President Van Buren, long a political adversary, though they maintained a cordial public relationship.[177]

The Republic of Texas won its independence from Mexico in the Texas Revolution of 1835–1836. Texas had largely been settled by Americans from the Southern United States, and many of those settlers owned slaves despite an 1829 Mexican law that abolished slavery. Many in the United States and Texas thus favored the admission of Texas into the union as a slave state. Adams considered the issue of Texas to be "a question of far deeper root and more overshadowing branches than any or all others that agitate the country", and he emerged as one of the leading congressional opponents of annexation. Adams had sought to acquire Texas when he served as secretary of state, but he argued that, because Mexico had abolished slavery, the acquisition of Texas would transform the region from a free territory into a slave state. He also feared that the annexation of Texas would encourage Southern expansionists to pursue other potential slave states, including Cuba. Adams's strong stance may have played a role in discouraging Van Buren from pushing for the annexation of Texas during his presidency.[178]

Whig nominee William Henry Harrison defeated Van Buren in the 1840 presidential election, and the Whigs gained control of both houses of Congress for the first time. Despite his low regard for Harrison as a person, Adams was enthusiastic about the new Whig administration and the end of the long-standing Democratic dominance of the federal government.[179] However, Harrison died in April 1841 and was succeeded by Vice President John Tyler, a Southerner who, unlike Adams, Henry Clay, and many other prominent Whigs, did not embrace the American System. Adams saw Tyler as an agent of "the slave-driving, Virginia, Jeffersonian school, principled against all improvement." After Tyler vetoed a bill to restore the national bank, Whig congressmen expelled Tyler from the party. Adams was appointed chairman of a special committee that explored impeaching Tyler, and Adams presented a scathing report of Tyler that argued that his actions warranted impeachment. The impeachment process did not move forward, though, in large part because the Whigs did not believe that the Senate would vote to remove Tyler from office.[180]

Opposition to the Mexican-American War, 1844–1848

Tyler made the annexation of Texas the main foreign policy priority of the later stages of his administration.[181] He attempted to win ratification of an annexation treaty in 1844, but, to Adams's surprise and relief, the treaty was rejected by the Senate.[182] The annexation of Texas became the central issue of the 1844 presidential election, and Southerners blocked the nomination of Van Buren at the 1844 Democratic National Convention due to the latter's opposition to annexation; the party instead nominated James K. Polk, an acolyte of Andrew Jackson.[183] Though he once again did not take part in the campaigning, Adams was deeply disappointed that Polk defeated his old ally, Henry Clay, in the 1844 election. He attributed the outcome of the election partly to the Liberty Party, a small, abolitionist third party that may have siphoned votes from Clay in the crucial state of New York.[184] After the election, Tyler, whose term would end in March 1845, once again submitted an annexation treaty to Congress.[lower-alpha 5] Adams strongly attacked the treaty, arguing that the annexation of Texas would involve the United States in "a war for slavery." Despite Adams's opposition, both houses of Congress approved the treaty, with most Democrats voting for annexation and most Whigs voting against it. Texas thus joined the United States as a slave state in 1845.[186]

Adams had served with James K. Polk in the House of Representatives, and Adams loathed the new president, seeing him as another expansionist, pro-slavery Southern Democrat.[187] Adams favored the annexation of the entirety of Oregon Country, a disputed region occupied by both the United States and Britain, and was disappointed when President Polk signed the Oregon Treaty, which divided the land between the two claimants at the 49th parallel.[188] Polk's expansionist aims were centered instead on the Mexican province of Alta California, and he attempted to buy the province from Mexico. The Mexican government refused to sell California or recognize the independence and subsequent American annexation of Texas. Polk deployed a military detachment led by General Zachary Taylor to back up his assertion that the Rio Grande constituted the Southern border of both Texas and the United States. After Taylor's forces clashed with Mexican soldiers north of the Rio Grande, Polk asked for a declaration of war in early 1846, asserting that Mexico had invaded American territory. Though some Whigs questioned whether Mexico had started an aggressive war, both houses of Congress declared war, with the House voting 174-to-14 to approve the declaration. Adams, who believed that Polk was seeking to wage an offensive to expand slavery, was one of the 14 dissenting votes.[189] After the start of the war, he supported the Wilmot Proviso, an unsuccessful legislative proposal that would have banned slavery in any territory ceded by Mexico.[190] After 1846, ill health increasingly affected Adams, but he continued to oppose the Mexican–American War until his death in 1848.[191]

Anti-slavery movement

In the 1830s, slavery emerged as an increasingly polarizing issue in the United States.[192] A longtime opponent of slavery, Adams used his new role in Congress to fight it, and he became the most prominent national leader opposing slavery.[193] After one of his reelection victories, he said that he must "bring about a day prophesied when slavery and war shall be banished from the face of the earth." He wrote in his private journal in 1820:[194]

The discussion of this Missouri question has betrayed the secret of their souls. In the abstract they admit that slavery is an evil, they disclaim it, and cast it all upon the shoulder of…Great Britain. But when probed to the quick upon it, they show at the bottom of their souls pride and vainglory in their condition of masterdom. They look down upon the simplicity of a Yankee's manners, because he has no habits of overbearing like theirs and cannot treat negroes like dogs. It is among the evils of slavery that it taints the very sources of moral principle. It establishes false estimates of virtue and vice: for what can be more false and heartless than this doctrine which makes the first and holiest rights of humanity to depend upon the color of the skin?

In 1836, partially in response to Adams's consistent presentation of citizen petitions requesting the abolition of slavery in the District of Columbia, the House of Representatives imposed a "gag rule" that immediately tabled any petitions about slavery. The rule was favored by Democrats and Southern Whigs but was largely opposed by Northern Whigs like Adams.[195] In late 1836, Adams began a campaign to ridicule slave owners and the gag rule. He frequently attempted to present anti-slavery petitions, often in ways that provoked strong reactions from Southern representatives.[196] Though the gag rule remained in place,[197] the discussion ignited by his actions and the attempts of others to quiet him raised questions of the right to petition, the right to legislative debate, and the morality of slavery. Adams fought actively against the gag rule for another seven years, eventually moving the resolution that led to its repeal in 1844.[198]

In 1841, at the request of Lewis Tappan and Ellis Gray Loring, Adams joined the case of United States v. The Amistad. Adams went before the Supreme Court on behalf of African slaves who had revolted and seized the Spanish ship Amistad. Adams appeared on February 24, 1841, and spoke for four hours. His argument succeeded: the Court ruled that the Africans were free and they returned to their homes.[199]

Smithsonian Institution

Adams also became a leading force for the promotion of science. In 1829, British scientist James Smithson died, and he left his fortune for the "increase and diffusion of knowledge." In Smithson's will, he stated that should his nephew, Henry James Hungerford, die without heirs, the Smithson estate would go to the government of the United States to create an "Establishment for the increase & diffusion of Knowledge among men." After the nephew died without heirs in 1835, President Andrew Jackson informed Congress of the bequest, which amounted to about US$500,000 ($75,000,000 in 2008 U.S. dollars after inflation). Adams realized that this might allow the United States to realize his dream of building a national institution of science and learning. Adams thus became Congress's primary supporter of the future Smithsonian Institution.[200]

The money was invested in shaky state bonds, which quickly defaulted. After heated debate in Congress, Adams successfully argued to restore the lost funds with interest.[201] Though Congress wanted to use the money for other purposes, Adams successfully persuaded Congress to preserve the money for an institution of science and learning. Congress also debated whether the federal government had the authority to accept the gift, though with Adams leading the initiative, Congress decided to accept the legacy bequeathed to the nation and pledged the faith of the United States to the charitable trust on July 1, 1836.[202] Partly due to Adams's efforts, Congress voted to establish the Smithsonian Institution in 1846. A nonpolitical board of regents was established to lead the institution, which included a museum, art gallery, library, and laboratory.[203]

Death

In mid-November 1846, the 78-year-old former president suffered a stroke that left him partially paralyzed. After a few months of rest, he made a full recovery and resumed his duties in Congress. When Adams entered the House chamber on February 13, 1848, everyone "stood up and applauded."[204]

On February 21, 1848, the House of Representatives was discussing the matter of honoring U.S. Army officers who served in the Mexican–American War. Adams had been a vehement critic of the war, and as Congressmen rose up to say, "Aye!" in favor of the measure, he instead yelled, "No!"[205] He rose to answer a question put forth by Speaker of the House Robert Charles Winthrop.[206] Immediately thereafter, Adams collapsed, having suffered a massive cerebral hemorrhage.[207] Two days later, on February 23, he died at 7:20 p.m. with his wife at his side in the Speaker's Room inside the Capitol Building in Washington, D.C.; his only living child, Charles Francis, did not arrive in time to see his father alive. His last words were "This is the last of earth. I am content."[206] Among those present for his death was Abraham Lincoln, then a freshman representative from Illinois.[208]

His original interment was temporary, in the public vault at the Congressional Cemetery in Washington, D.C. Later, he was interred in the family burial ground in Quincy, Massachusetts, across from the First Parish Church, called Hancock Cemetery. After Louisa's death in 1852, his son had his parents reinterred in the expanded family crypt in the United First Parish Church across the street, next to John and Abigail. Both tombs are viewable by the public. Adams's original tomb at Hancock Cemetery is still there and marked simply "J.Q. Adams".[209]

Personal life

Adams and Louisa had three sons and a daughter. Their daughter, Louisa, was born in 1811 but died in 1812.[210] They named their first son George Washington Adams (1801–1829) after the first president. This decision upset Adams's mother, and, by her account, his father as well.[211] Both George and their second son, John (1803–1834), led troubled lives and died in early adulthood.[212][213] George, who had long suffered from alcoholism, died in 1829 after going overboard on a steamboat; it is not clear whether he fell or purposely jumped from the boat.[214] John, who ran an unprofitable flour and grist mill owned by his father, died of an unknown illness in 1834.[215] Adams's youngest son, Charles Francis Adams Sr., was an important leader of the "Conscience Whigs", a Northern, anti-slavery faction of the Whig Party.[191] Charles served as the Free Soil Party's vice presidential candidate in the 1848 presidential election and later became a prominent member of the Republican Party.[216]

Personality

Adams's personality and political beliefs were much like his father's.[217] He always preferred secluded reading to social engagements, and several times had to be pressured by others to remain in public service. Historian Paul Nagel states that, like Abraham Lincoln after him, Adams often suffered from depression, for which he sought some form of treatment in early years. Adams thought his depression was due to the high expectations demanded of him by his father and mother. Throughout his life he felt inadequate and socially awkward because of his depression, and was constantly bothered by his physical appearance.[217] He was closer to his father, whom he spent much of his early life with abroad, than he was to his mother. When he was younger and the American Revolution was going on, his mother told her children what their father was doing, and what he was risking, and because of this Adams grew to greatly respect his father.[217] His relationship with his mother was rocky; she had high expectations of him and was afraid her children might end up dead alcoholics like her brother.[217] His biographer, Nagel, concludes that his mother's disapproval of Louisa Johnson motivated him to marry Johnson in 1797, despite Adams's reservations that Johnson, like his mother, had a strong personality.[217]

Though Adams wore a powdered wig in his youth,[218] he abandoned this fashion and became the first president to adopt a short haircut instead of long hair tied in a queue and to regularly wear long trousers instead of knee breeches.[219][220] It has been suggested that John Quincy Adams had the highest I.Q. of any U.S. president.[221][222] Dean Simonton, a professor of psychology at UC Davis, estimated his I.Q. score at 165.[223]

Legacy

Historical reputation

Adams is widely regarded as one of the most effective diplomats and secretaries of state in American history,[224][225] but scholars generally rank him as an average president.[226][227] Adams is remembered as a man eminently qualified for the presidency, yet hopelessly weakened in his presidential leadership potential because of the 1824 election. Most importantly, Adams is remembered as a poor politician in an era when politics had begun to matter more. He spoke of trying to serve as a man above the "baneful weed of party strife" at the precise moment in history when the Second Party System was emerging with nearly revolutionary force.[163] Biographer and historian William J. Cooper notes that Adams "does not loom large in the American imagination", but that he has received more public attention since the late 20th century due to his anti-slavery stances. Cooper writes that Adams was the first "major public figure" to publicly question whether the United States could remain united so long as the institution of slavery persisted.[224] Historian Daniel Walker Howe writes that Adams's "intellectual ability and courage were above reproach, and his wisdom in perceiving the national interest has stood the test of time."[228] Historians have often included Adams among the leading conservatives of his day.[229][230][231][232] Russell Kirk, however, sees Adams as a flawed conservative who was imprudent in opposing slavery.[229]

Memorials

John Quincy Adams Birthplace is now part of Adams National Historical Park and open to the public. Adams House, one of twelve undergraduate residential Houses at Harvard University, is named for John Adams, John Quincy Adams, and other members of the Adams family associated with Harvard.[233] In 1870, Charles Francis built the first presidential library in the United States, to honor his father. The Stone Library includes over 14,000 books written in twelve languages. The library is located in the "Old House" at Adams National Historical Park in Quincy, Massachusetts.

Adams's middle name of Quincy has been used by several locations in the United States, including the town of Quincy, Illinois. Adams County, Illinois and Adams County, Indiana are also named after Adams. Adams County, Iowa, and Adams County, Wisconsin, were each named for either John Adams or John Quincy Adams.

Some sources contend that in 1843 Adams sat for the earliest confirmed photograph of a U.S. president, although others maintain that William Henry Harrison had posed even earlier for his portrait, in 1841.[234] The original daguerreotype is in the collection of the National Portrait Gallery of the Smithsonian Institution.[235]

Film and television

Adams occasionally is featured in the mass media. In the PBS miniseries The Adams Chronicles (1976), he was portrayed by David Birney, William Daniels, Marcel Trenchard, Steven Grover and Mark Winkworth. He was also portrayed by Anthony Hopkins in the 1997 film Amistad, and again by Ebon Moss-Bachrach and Steven Hinkle in the 2008 HBO television miniseries John Adams; the HBO series received criticism for needless historical and temporal distortions in its portrayal.[236]

See also

- List of abolitionists

- List of United States political appointments across party lines

- List of Presidents of the United States by previous experience

- List of United States Congress members who died in office (1790–1899)

- Mendi Bible

- Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft

Notes

- The Quincy family name was pronounced /ˈkwɪnzi/, as in the name of Quincy, Massachusetts (then called Braintree), where Adams was born. All of the other Quincy place names are locally /ˈkwɪnsi/. Though not accurate, this pronunciation is also commonly used for Adams's middle name.[2]

- When Adams took office as president in 1825, Louisa became the first First Lady born outside of the United States. In 2017, Melania Trump became the second First Lady born outside of the United States.[25]

- Adams had been especially concerned by the Hartford Convention, which had been called by anti-war Federalists to discuss their grievances against the Madison administration[63]

- In 2001, George W. Bush would become the second child of a president to serve as president.

- Tyler had initially sent the treaty to the Senate; the Constitution provides that a two-thirds vote of the Senate is required to ratify any treaty. After the 1844 election, Tyler asked Congress to approve the treaty via joint resolution, which would require a simple majority vote in both houses of Congress.[185]

References

- "John Quincy Adams; Biographical Directory of the U.S. Congress". Bioguide.congress.gov. Retrieved March 15, 2017.

- Wead, Doug (2005). The Raising of a President. New York: Atria Books. p. 59. ISBN 0-7434-9726-0.

- Quincy, Mailing Address: 135 Adams Street. "John Quincy Adams Birthplace - Adams National Historical Park (U.S. National Park Service)". www.nps.gov. Retrieved March 4, 2020.

- Rettig, Polly M. (April 3, 1978). "John Quincy Adams Birthplace". National Park Service. Retrieved November 1, 2011.

- Herring, James; Longacre, James Barton (1853). The National Portrait Gallery of Distinguished Americans. D. Rice & A.N. Hart. p. 1. ISBN 0-405-02500-9.

- Remini 2002

- "The Diaries of John Quincy Adams: A Digital Collection". Massachusetts Historical Society. Retrieved October 30, 2011.

- Cooper 2017, pp. 5–8.

- Richard, Carl (2009). The Golden Age of the Classics in America: Greece Rome and the Antebellum United States. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. p. 23. ISBN 978-0674032644.

- Cooper 2017, pp. 8–9, 16.

- Cooper 2017, pp. 9, 14–16.

- Cooper 2017, pp. 17–18.

- Cooper 2017, pp. 21–22.

- Edel 2014, pp. 36–37.

- Cooper 2017, pp. 24–27.

- Musto, David F. (April 20, 1968). "The Youth of John Quincy Adams". Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: American Philosophical Society. 113: 273. PMID 11615552.

- Cooper 2017, pp. 29–30.

- Cooper 2017, pp. 32–33.

- Cooper 2017, pp. 35–36.

- Cooper 2017, p. 38.

- Edel 2014, pp. 83–86.

- Cooper 2017, pp. 34, 40–41.

- Cooper 2017, pp. 45–48.

- Cooper 2017, pp. 48–53.

- Black, Allida (2009). "The First Ladies of the United States of America". The White House Historical Assoc.

- Cooper 2017, pp. 54–55.

- Cooper 2017, pp. 48–49.

- Edel 2014, p. 83.

- Cooper 2017, pp. 53–56.

- Cooper 2017, pp. 59–60.

- Cooper 2017, pp. 60–61.

- Edel 2014, p. 89.

- Cooper 2017, pp. 64–66.

- McCullough 2001, pp. 575–76.

- Cooper 2017, pp. 67–68.

- Cooper 2017, pp. 70–71.

- "John Quincy Adams Isn't Who You Think He Is". Bloomberg.com. February 8, 2020. Retrieved March 14, 2020.

- Thompson 1991, pp. 165–181

- McCullough 2001, p. 587.

- Rathbun, Lyon (2000). "The Ciceronian Rhetoric of John Quincy Adams". Rhetorica. 18 (2): 175–215. doi:10.1525/rh.2000.18.2.175.

- Hume, David (1742). Essays and Treatises on Several Subjects. London: T. Cadell. pp. 99–110.

- Potkay, Adam S. (1999). "Theorizing Civic Eloquence in the Early Republic: the Road from David Hume to John Quincy Adams". Early American Literature. 34 (2): 147–70.

- Cooper 2017, p. 85.

- Cooper 2017, pp. 87–88.

- Edel 2014, pp. 96–97.

- Cooper 2017, pp. 88–89.

- Cooper 2017, pp. 91–92.

- Cooper 2017, pp. 90, 94–95.

- Cooper 2017, pp. 92–93.

- McMillion, Barry J.; Rutkus, Denis Steven (July 6, 2018). "Supreme Court Nominations, 1789 to 2017: Actions by the Senate, the Judiciary Committee, and the President" (PDF). Washington, D.C.: Congressional Research Service. Retrieved August 26, 2018.

- Cooper 2017, pp. 106–107.

- Cooper 2017, pp. 109–110.

- Cooper 2017, pp. 112–113.

- Cooper 2017, pp. 112, 114–115, 119.

- Cooper 2017, pp. 116–118.

- Kaplan 2014, pp. 289–302

- Cooper 2017, pp. 127–128.

- Kaplan 2014, pp. 307–11, 318–20

- Edel 2014, pp. 116–17.

- James E. Lewis Jr, John Quincy Adams: Policymaker for the Union (2001) p 56.

- Kaplan 2014, pp. 321–22.

- Cooper 2017, pp. 143–145.

- Cooper 2017, pp. 145–146.

- Edel 2014, pp. 107–09.

- Cooper 2017, pp. 147–148.

- Kaplan 2014, pp. 327–28.

- Cooper 2017, pp. 151–152.

- Cooper 2017, pp. 153–154.

- Cooper 2017, pp. 154–155.

- Remini 2002, pp. 48, 51–53.

- Kaplan 2014, pp. 333–37, 348.

- Cooper 2017, pp. 163–164.

- Howe 2007, p. 106

- Cooper 2017, pp. 164–166.

- Howe 2007, pp. 108–109

- Cooper 2017, pp. 167–168.

- Howe 2007, pp. 112–115

- Kaplan 2014, pp. 380–85.

- Howe 2007, pp. 115–116

- Kaplan 2014, pp. 364–67.

- Howe 2007, pp. 203–204

- Parsons 2009, pp. 70–72.

- Hargreaves 1985, p. 24

- Cooper 2017, pp. 208–209.

- Hargreaves 1985, pp. 20–21

- Parsons 2009, pp. 79–86.

- Kaplan 2014, pp. 386–389.

- Cooper 2017, p. 213.

- "John Quincy Adams: Campaigns and Elections". Miller Center of Public Affairs, University of Virginia. October 4, 2016. Retrieved March 28, 2017.

- Hargreaves 1985, pp. 33–34, 36–38

- Kaplan 2014, pp. 391–393, 398.

- Cooper 2017, p. 217.

- "John Quincy Adams Takes the Oath of Office – Wearing Pants". New England Historical Society. March 4, 2015. Retrieved March 9, 2017.

- Kaplan 2014, pp. 394–96.

- Hargreaves 1985, p. 62–64

- Hargreaves 1985, pp. 47–48

- Hargreaves 1985, p. 49–50

- Parsons 2009, pp. 106–107.

- Hargreaves 1985, pp. 48–49

- Kaplan 2014, pp. 396–397.

- Howe 2007, pp. 247–248

- First Annual Message; John Quincy Adams; speech transcript; (1825); via Peters, Gerhard and Woolley, John T.; The American Presidency Project online; University of California Santa Barbara; accessed January 2020

- Kaplan 2014, pp. 402–403.

- Remini 2002, pp. 80–81.

- Hargreaves 1985, pp. 311–314

- Kaplan 2014, pp. 404–405.

- Kaplan 2014, pp. 397–398.

- Remini 2002, pp. 84–86.

- Hargreaves 1985, p. 167

- Hargreaves 1985, p. 173

- Hargreaves 1985, pp. 173–174

- Hargreaves 1985, pp. 176–177

- Remini 2002, pp. 85–86.

- Parsons 2009, pp. 105–106.

- Parsons 2009, pp. 110–111.

- Howe 2007, pp. 249–250

- Parsons 2009, pp. 114–115.

- Parsons 2009, pp. 119–120.

- Parsons 2009, pp. 138–139.

- Remini 2002, pp. 84–85.

- Howe 2007, p. 251

- Parsons 2009, pp. 125–126.

- Parsons 2009, pp. 146–147.

- Remini 2002, pp. 110–111.

- Parsons 2009, pp. 127–128.

- Howe 2007, pp. 279–280

- Parsons 2009, pp. 141–142.

- Hargreaves 1985, pp. 189–191

- Remini, Robert V. (July 1958). "Martin Van Buren and the Tariff of Abominations". The American Historical Review. 63 (4): 903–917. doi:10.2307/1848947. JSTOR 1848947.

- Parsons 2009, pp. 157–158.

- Edel 2014, pp. 225–226

- Kaplan 2014, pp. 398–400.

- Howe 2007, p. 256

- Hargreaves 1985, pp. 101–101

- Hargreaves 1985, pp. 67–68

- Hargreaves 1985, pp. 76–85

- Hargreaves 1985, pp. 91–95

- Kaplan 2014, pp. 400–401.

- Hargreaves 1985, pp. 102–107

- Hargreaves 1985, pp. 110–112

- Cooper 2017, pp. 240–241.

- Howe 2007, p. 257

- Kaplan 2014, pp. 401–402.

- Remini 2002, pp. 82–83.

- Cooper 2017, p. 229.

- Kaplan 2014, pp. 408–410.

- Howe 2007, pp. 275–277

- Parsons 2009, pp. 152–154.

- Parsons 2009, pp. 142–143.

- Parsons 2009, pp. 143–144.

- Parsons 2009, pp. 166–167.

- Howe 2007, pp. 278–279

- Hargreaves 1985, pp. 283–284

- Parsons 2009, pp. 171–172.

- Parsons 2009, pp. 181–183.

- Howe 2007, pp. 281–283

- Howe 2007, pp. 276, 280–281

- Edel 2014, pp. 254–56.

- Kaplan 2014, pp. 445–446.

- Cooper 2017, pp. 288–289, 345–346.

- Edel 2014, pp. 258–59.

- Kaplan 2014, pp. 450–52.