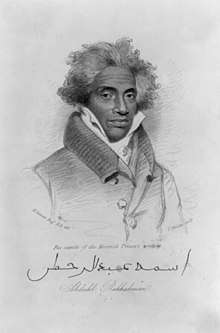

Abdulrahman Ibrahim Ibn Sori

Abdul-Rahman ibn Ibrahima Sori (Arabic: عبد الرحمن ابن ابراهيم سوري) (1762–1829) was an African prince and Amir (commander or governor) who was captured in the Fouta Jallon region of Guinea, West Africa and sold to slave traders in the United States in 1788.[1] Upon discovering his noble lineage, his slave master Thomas Foster[2], began referring to him as "Prince",[3] a title he kept until his final days. After spending 40 years in slavery, he was freed in 1828 by order of U.S. President John Quincy Adams and Secretary of State Henry Clay after the Sultan of Morocco requested his release.[4]

Abdulrahman Ibrahim Ibn Sori | |

|---|---|

Drawing of Abdul-Rahman ibn Ibrahim Sori. The Arabic inscription reads "His name is Abd al-Rahman". | |

| Amir | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 1762 Timbo |

| Died | 1829 (aged 67) Monrovia, Liberia |

| Cause of death | Fever |

| Spouse(s) | Isabella

( m. 1794; death 1829) |

| Children | 10 |

| Father | Ibrahim Sori |

Life

Abdul-Rahman ibn Ibrahim Sori was a Torodbe Muslim ruler (Emir)[5] born in 1762 in the city of Timbo, now located in Guinea.[6] His father, Almami Ibrahim Sori consolidated the Islamic confederation of Futa Jallon in 1776, with Timbo as its capital, where Abdul Rahman lived and studied. "He was learned in the Islamic sciences and could speak at least 4 different African languages, in addition to Arabic and English, and in 1781, after returning from study in the renowned city of learning-Timbuktu, Abd'r-Rahman joined the armies of his father."[5] At age 26, he was made an Emir of one of the regiments that conquered the lands of the Bambara and in 1788 his father "made him the head of a 2000 men army whose mission was to protect the coast and strengthen their economic interest in the region. It was during this military campaign that Abd'r-Rahman was captured and enslaved."[5] He was sold to the British who brought him to Natchez, Mississippi where he labored on the cotton plantation of Thomas Foster for more than thirty-eight years before gaining his freedom.[7] In 1794 he married Isabella, another slave of Foster's, and eventually fathered a large family: five sons and four daughters.[8]

By using his knowledge of growing cotton in Futa Jallon, Abdul-Rahman rose to a position of authority on the plantation and became the de facto foreman. This granted him the opportunity to grow his own vegetable garden and sell at the local market. During this time, he met an old acquaintance, Dr. John Cox, an Irish surgeon who had served on an English ship, and had become the first white man to reach Timbo after being abandoned by his ship and then falling ill. Cox stayed ashore for six months and was taken in by Abdul-Rahman's family, where he was tasked to teach Abdul-Rahman English. Cox appealed to Foster to sell his "Prince" so he could return to Africa. However, Foster would not budge, since he viewed Abdul-Rahman as indispensable to the Foster farm. Dr. Cox continued, until his death in 1816, to seek Ibrahim's freedom, to no avail. After Cox died, his son continued the cause to free Abdul-Rahman.

In 1826, Abdul-Rahman wrote a letter to his relatives in Africa. A local newspaperman, Andrew Marschalk, who was Dutch, sent the letter to United States Senator Thomas Reed from Mississippi, who was in town at the time, and Reed forwarded it to the U.S. Consulate in Morocco. Since Abdul-Rahman wrote in Arabic, Marschalk and the U.S. government assumed that he was a Moor. After the Sultan of Morocco Abderrahmane read the letter, he asked President Adams and Secretary of State Henry Clay to release Abdul-Rahman. In 1829, Thomas Foster agreed to the release of Abdul-Rahman, without payment, with the stipulation that he return to Africa and not live as a free man in America.

Before leaving the US, Abdul-Rahman and his wife went to various states and Washington, D.C. where he met with President Adams in person. He solicited donations, through the press, personal appearances, the American Colonization Society and politicians, to free his family back in Mississippi. Word got back to Foster, who considered this a breach of the agreement. Abdul-Rahman's actions and freedom were also used against President John Quincy Adams by future president Andrew Jackson during the presidential election.

After ten months, Abdul-Rahman and Isabella had raised only half the funds to free their children, and instead left for Monrovia, Liberia, without their children. He lived for four months before contracting a fever and died at the age of 67. He never saw Fouta Djallon or his children again.

The funds that Abdul-Rahman and Isabella raised only bought the freedom of two sons and their families. They were reunited with Isabella in Monrovia. Thomas Foster died the same year as Abdul-Rahman. Foster's estate, including Abdul-Rahman's other children and grandchildren, was divided among Foster's heirs and scattered across Mississippi and the South. Abdul-Rahman's descendants still reside in Monrovia and in Natchez Mississippi United States. In 2006, Abdul-Rahman's descendants gathered for a family reunion at Foster's Field.

Legacy

Abdul-Rahman (Prince Sori), wrote two autobiographies. A drawing of him is displayed in the Library of Congress, a roadmap which one can say was left for his descendants to follow as they reconnect to the Royal lineages.

Prince Sori's legacy stretches from Natchez Mississippi to Monrovia Liberia and with the advancements of Deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA), his descendants have been able to connect with each other such as; his Great-Grandchildren Six generation(s), Dr. Artemus Gaye of Monrovia & Karen Chatman of Natchez Mississippi.

In 1968, James Register, who had been born in Natchez, wrote the first full account of Abdul-Rahman's life in his book Jallon: Arabic Prince of Old Natchez (1788 - 1828). In 1977, history professor Terry Alford further documented the life of Abdul-Rahman in his book Prince Among Slaves. In Prince Among Slaves, Alford writes:

Among Henry Clay's documents, for the year 1829 we find the January 1 entry, "Prince Ibrahima, an Islamic prince sold into slavery 15 years ago, and freed with the stipulation that he return (in this case the word "return" makes sense) to Africa, joined the black citizens of Philadelphia as an honored guest in their New Year's Day parade, up Lombard and Walnut, and down Chestnut and Spruce streets.

— Terry Alford, Prince Among Slaves

In 2007, Andrea Kalin directed Prince Among Slaves, a film portraying the life of Abdul-Rahman, narrated by Mos Def.

In 2018 Dr. Artemus Gaye of Monrovia Liberia released Rooted Beyond Boundaries, a book which details factual accounts of his (6) generation Grandfather life while as a slave and as a freed man; these accounts have never been shared or told as they have by his own family.

Dr. Gaye and Karen Chatman of Natchez, Mississippi, descendants of Abdul-Rahman: uses the Royal titles which were inherited from Prince Sori and recognized by the United Nations and the United States of America to promote charitable organizations such as the Obama Foundation and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation in their personal quest to combat humanitarian issues. Chatman, a United States born citizen, founded the Princess Karen Foundation of Global and Ancestry Development, Global Paths Foundation, an organization that encourages unity amongst children ages fourteen to eighteen by working with school officials and corporate partners to bring awareness of common cultural and racial bonds and Think Pink International. Chatman is the author of "Chained Free."

See also

- Islam in the United States

- List of slaves

- Slavery in the United States

References

- Diouf 1998, p. 27–28.

- Find a Grave, database and images (https://www.findagrave.com : accessed 14 May 2020), memorial page for Thomas Foster, Sr (10 Sep 1762–1 Sep 1829), Find a Grave Memorial no. 166608252, citing Thomas Foster, Natchez, Adams County, Mississippi, USA ; Maintained by Jackie Weiss (contributor 49056576).

- Austin 1997, p. 71.

- Diouf 1998, p. 137.

- Shareef, Muhammad (2004). "The Lost and Found Children of Abraham in Africa and the American Diaspora" (PDF). siiasi.org. Sankore Institute of Islamic African Studies International (SIIASI). Retrieved 12 November 2016.

- Austin 1997, p. 69.

- Austin 1997, p. 65.

- "Prince Among Slaves". PBS. Archived from the original on February 14, 2008.

Bibliography

- Austin, Allan (1997). African Muslims in Antebellum America (5th ed.). New York, NY: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-91269-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Diouf, Sylviane (1998). Servants of Allah: African Muslims Enslaved in the Americas. New York and London: New York University Press. ISBN 0-8147-1905-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

- Prince Among Slaves Official Movie Site

- MuslimWiki Ibrahim Abd ar-Rahman

- IMDb Prince Among Slaves (2006)

- Prince Among Slaves | PBS

- Film Challenges Convention on Muslims, Africans, Slave-Era America

- Princess Karen Foundation