Presidency of Dwight D. Eisenhower

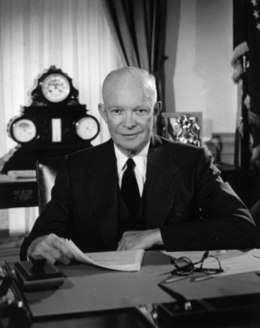

The presidency of Dwight D. Eisenhower began at noon EST on January 20, 1953, with his inauguration as the 34th president of the United States, and ended on January 20, 1961. Eisenhower, a Republican, took office as president following his victory over Democrat Adlai Stevenson in the 1952 presidential election. John F. Kennedy succeeded him after winning the 1960 presidential election.

| |

| Presidency of Dwight D. Eisenhower | |

|---|---|

| January 20, 1953 – January 20, 1961 | |

| President | Dwight D. Eisenhower |

| Cabinet | See list |

| Party | Republican |

| Election | 1952, 1956 |

| Seat | White House |

| |

| Seal of the President (since 1960) | |

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

World War II

President of the United States

First Term

Second Term

Post-Presidency

|

||

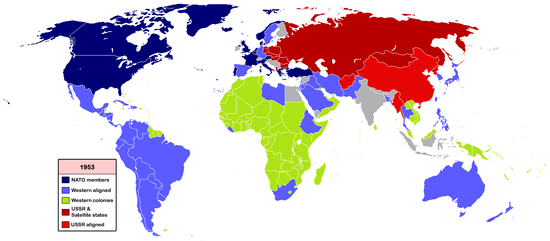

Eisenhower held office during the Cold War, a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union. Eisenhower's New Look policy stressed the importance of nuclear weapons as a deterrent to military threats, and the United States built up a stockpile of nuclear weapons and nuclear weapons delivery systems during Eisenhower's presidency. Soon after taking office, Eisenhower negotiated an end to the Korean War, resulting in the partition of Korea. Following the Suez Crisis, Eisenhower promulgated the Eisenhower Doctrine, strengthening U.S. commitments in the Middle East. In response to the Cuban Revolution, the Eisenhower administration broke ties with Cuba and began preparations for an invasion of Cuba by Cuban exiles, eventually resulting in the failed Bay of Pigs Invasion. Eisenhower also allowed the Central Intelligence Agency to engage in covert actions, such as the 1953 Iranian coup d'état and the 1954 Guatemalan coup d'état.

In domestic affairs, Eisenhower supported a policy of "modern Republicanism" that occupied a middle ground between liberal Democrats and the conservative wing of the Republican Party. Eisenhower continued New Deal programs, expanded Social Security, and prioritized a balanced budget over tax cuts. He played a major role in establishing the Interstate Highway System, a massive infrastructure project consisting of tens of thousands of miles of divided highways. After the launch of Sputnik 1, Eisenhower signed the National Defense Education Act and presided over the creation of NASA. Though he did not embrace the Supreme Court's landmark desegregation ruling in the 1954 case of Brown v. Board of Education, Eisenhower enforced the Court's holding and signed the first significant civil rights bill since the end of Reconstruction.

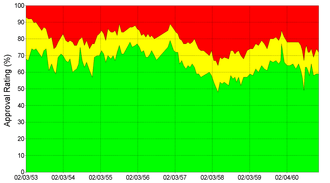

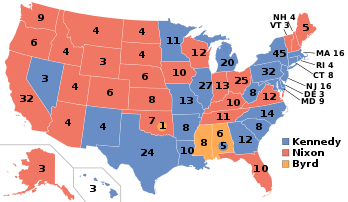

Eisenhower won the 1956 presidential election in a landslide and maintained positive approval ratings throughout his tenure, but the launch of Sputnik 1 and a poor economy contributed to Republican losses in the 1958 elections. In the 1960 presidential election, Vice President Richard Nixon lost by a narrow margin to Kennedy. Eisenhower left office popular with the public but viewed by many commentators as a "do-nothing" president. His reputation improved after the release of his private papers in the 1970s. Polls of historians and political scientists rank Eisenhower in the top quartile of presidents.

Election of 1952

Republican nomination

Going into the 1952 Republican presidential primaries, the two major contenders for the Republican presidential nomination were General Dwight D. Eisenhower and Senator Robert A. Taft of Ohio. Governor Earl Warren of California and former Governor Harold Stassen of Minnesota also sought the nomination.[1] Taft led the conservative wing of the party, which rejected many of the New Deal social welfare programs created in the 1930s and supported a noninterventionist foreign policy. Taft had been a candidate for the Republican nomination twice before but had been defeated both times by moderate Republicans from New York: Wendell Willkie in 1940 and Thomas E. Dewey in 1948.[2]

Dewey, the party's presidential nominee in 1944 and 1948, led the moderate wing of the party, centered in the Eastern states. These moderates supported most of the New Deal and tended to be interventionists in the Cold War. Dewey himself declined to run for president a third time, but he and other moderates sought to use his influence to ensure that 1952 Republican ticket hewed closer to their wing of the party.[2] To this end, they assembled a Draft Eisenhower movement in September 1951. Two weeks later, at the National Governors' Conference meeting, seven Republican governors endorsed his candidacy.[3] Eisenhower, then serving as the Supreme Allied Commander of NATO, had long been mentioned as a possible presidential contender, but he was reluctant to become involved in partisan politics.[4] Nonetheless, he was troubled by Taft's non-interventionist views, especially his opposition to NATO, which Eisenhower considered to be an important deterrence against Soviet aggression.[5] He was also motivated by the corruption that he believed had crept into the federal government during the later years of the Truman administration.[6]

Eisenhower suggested in late 1951 that he would not oppose any effort to nominate him for president, although he still refused to seek the nomination actively.[7] In January 1952, Senator Henry Cabot Lodge Jr. announced that Eisenhower's name would be entered in the March New Hampshire primary, even though he had not yet officially entered the race.[1] The result in New Hampshire was a solid Eisenhower victory with 46,661 votes to 35,838 for Taft and 6,574 for Stassen.[8] In April, Eisenhower resigned from his NATO command and returned to the United States. The Taft forces put up a strong fight in the remaining primaries, and, by the time of the July 1952 Republican National Convention, it was still unclear whether Taft or Eisenhower would win the presidential nomination.[9]

When the 1952 Republican National Convention opened in Chicago, Eisenhower's managers accused Taft of "stealing" delegate votes in Southern states, claiming that Taft's allies had unfairly denied delegate spots to Eisenhower supporters and put Taft delegates in their place. Lodge and Dewey proposed to evict the pro-Taft delegates in these states and replace them with pro-Eisenhower delegates; they called this proposal "Fair Play." Although Taft and his supporters angrily denied this charge, the convention voted to support Fair Play 658 to 548, and Taft lost many Southern delegates. Eisenhower also received two more boosts: first when several uncommitted state delegations, such as Michigan and Pennsylvania, decided to support him; and second, when Stassen released his delegates and asked them to support Eisenhower. The removal of many pro-Taft Southern delegates and the support of the uncommitted states decided the nomination in Eisenhower's favor, which he won on the first ballot. Afterward, Senator Richard Nixon of California was nominated by acclamation as his vice-presidential running mate.[10] Nixon, whose name came to the forefront early and often in preconvention conversations among Eisenhower's campaign managers, was selected because of his youth (39 years old) and solid anti-communist record.[11]

General election

Incumbent President Harry S. Truman announced his retirement in March 1952, making it unclear who would win the Democratic presidential nomination.[12] Delegates to the 1952 Democratic National Convention, also held in Chicago, nominated Illinois governor Adlai E. Stevenson for president on the third ballot. Senator John Sparkman of Alabama was selected as his running mate. The convention ended with widespread confidence that the party had selected a powerful presidential contender who would field a competitive campaign.[13] Stevenson concentrated on giving a series of thoughtful speeches around the nation. Although his style thrilled intellectuals and academics, some political experts wondered if he were speaking "over the heads" of most of his listeners, and they dubbed him an "egghead," based on his baldness and intellectual demeanor. His biggest liability however, was the unpopularity of the incumbent president, Harry Truman. Even though Stevenson had not had been a part of the Truman administration, voters largely ignored his record and burdened him with Truman's. Historian Herbert Parmet says that Stevenson:

failed to dispel the widespread recognition that, for a divided America, torn by paranoia and unable to understand what had disrupted the anticipated tranquility of the postwar world, the time for change had really arrived. Neither Stevenson nor anyone else could have dissuaded the electorate from its desire to repudiate 'Trumanism.'[14]

Republican strategy during the fall campaign focused on Eisenhower's unrivaled popularity.[15] Ike traveled to 45 of the 48 states; his heroic image and plain talk excited the large crowds who heard him speak from the campaign train's caboose. In his speeches, Eisenhower never mentioned Stevenson by name, instead relentlessly attacking the alleged failures of the Truman administration: "Korea, Communism, and corruption."[16] In addition to the speeches, he got his message out to voters through 30-second television advertisements; this was the first presidential election in which television played a major role.[17] In domestic policy, Eisenhower attacked the growing influence of the federal government in the economy, while in foreign affairs, he supported a strong American role in stemming the expansion of Communism. Eisenhower adopted much of the rhetoric and positions of the contemporary GOP, and many of his public statements were designed to win over conservative supporters of Taft.[18]

A potentially devastating allegation hit when Nixon was accused by several newspapers of receiving $18,000 in undeclared "gifts" from wealthy California donors. Eisenhower and his aides considered dropping Nixon from the ticket and picking another running mate. Nixon responded to the allegations in a nationally televised speech, the "Checkers speech," on September 23. In this speech, Nixon denied the charges against him, gave a detailed account of his modest financial assets, and offered a glowing assessment of Eisenhower's candidacy. The highlight of the speech came when Nixon stated that a supporter had given his daughters a gift—a dog named "Checkers"—and that he would not return it, because his daughters loved it. The public responded to the speech with an outpouring of support, and Eisenhower retained him on the ticket.[19][20]

Ultimately, the burden of the ongoing Korean War, Communist threat, and Truman administration scandals, as well as the popularity of Eisenhower, were too much for Stevenson to overcome.[21] Eisenhower won a landslide victory, taking 55.2 percent of the popular vote and 442 electoral votes. Stevenson received 44.5 percent of the popular vote and 89 electoral votes. Eisenhower won every state outside of the South, as well as Virginia, Florida, and Texas, each of which voted Republican for just the second time since the end of Reconstruction. In the concurrent congressional elections, Republicans won control of the House of Representatives and the Senate.[22]

Administration

Cabinet

| The Eisenhower Cabinet | ||

|---|---|---|

| Office | Name | Term |

| President | Dwight D. Eisenhower | 1953–1961 |

| Vice President | Richard Nixon | 1953–1961 |

| Secretary of State | John Foster Dulles | 1953–1959 |

| Christian Herter | 1959–1961 | |

| Secretary of the Treasury | George M. Humphrey | 1953–1957 |

| Robert B. Anderson | 1957–1961 | |

| Secretary of Defense | Charles Erwin Wilson | 1953–1957 |

| Neil H. McElroy | 1957–1959 | |

| Thomas S. Gates Jr. | 1959–1961 | |

| Attorney General | Herbert Brownell Jr. | 1953–1957 |

| William P. Rogers | 1957–1961 | |

| Postmaster General | Arthur Summerfield | 1953–1961 |

| Secretary of the Interior | Douglas McKay | 1953–1956 |

| Fred A. Seaton | 1956–1961 | |

| Secretary of Agriculture | Ezra Taft Benson | 1953–1961 |

| Secretary of Commerce | Sinclair Weeks | 1953–1958 |

| Frederick H. Mueller | 1959–1961 | |

| Secretary of Labor | Martin Patrick Durkin | 1953 |

| James P. Mitchell | 1953–1961 | |

| Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare | Oveta Culp Hobby | 1953–1955 |

| Marion B. Folsom | 1955–1958 | |

| Arthur Sherwood Flemming | 1958–1961 | |

| Ambassador to the United Nations | Henry Cabot Lodge Jr. | 1953–1960 |

| James Jeremiah Wadsworth | 1960–1961 | |

Eisenhower delegated the selection of his cabinet to two close associates, Lucius D. Clay and Herbert Brownell Jr. Brownell, a legal aide to Dewey, became attorney general.[23] The office of Secretary of State went to John Foster Dulles, a long-time Republican spokesman on foreign policy who had helped design the United Nations Charter and the Treaty of San Francisco. Dulles would travel nearly 560,000 miles (901,233 km) during his six years in office.[24] Outside of the cabinet, Eisenhower selected Sherman Adams as White House Chief of Staff, and Milton S. Eisenhower, the president's brother and a prominent college administrator, emerged as an important adviser.[25] Eisenhower also elevated the role of the National Security Council, and designated Robert Cutler to serve as the first National Security Advisor.[26]

Eisenhower sought out leaders of big business for many of his other cabinet appointments. Charles Erwin Wilson, the CEO of General Motors, was Eisenhower's first secretary of defense. In 1957, he was replaced by president of Procter & Gamble, Neil H. McElroy. For the position of secretary of the treasury, Ike selected George M. Humphrey, the CEO of several steel and coal companies. His postmaster general, Arthur E. Summerfield, and first secretary of the interior, Douglas McKay, were both automobile distributors. Former senator, Sinclair Weeks, became Secretary of Commerce.[23] Eisenhower appointed Joseph Dodge, a longtime bank president who also had extensive government experience, as the director of the Bureau of the Budget. He became the first budget director to be given cabinet-level status.[27]

Other Eisenhower cabinet selections provided patronage to political bases. Ezra Taft Benson, a high-ranking member of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, was chosen as secretary of agriculture; he was the only person appointed from the Taft wing of the party. As the first secretary of the new Department of Health, Education, and Welfare (HEW), Eisenhower named the wartime head of the Army's Women's Army Corps, Oveta Culp Hobby. She was the second woman to ever be a cabinet member. Martin Patrick Durkin, a Democrat and president of the plumbers and steamfitters union, was selected as secretary of labor.[23] As a result, it became a standing joke that Eisenhower's inaugural Cabinet was composed of "nine millionaires and a plumber."[28] Dissatisfied with Eisenhower's labor policies, Durkin resigned after less than a year in office, and was replaced by James P. Mitchell.[29]

Vice presidency

Eisenhower, who disliked partisan politics and politicians, left much of the building and sustaining of the Republican Party to Vice President Nixon.[30] Eisenhower knew how ill-prepared Vice President Truman had been on major issues such as the atomic bomb when he suddenly became president in 1945, and therefore made sure to keep Nixon fully involved in the administration. He gave Nixon multiple diplomatic, domestic, and political assignments so that he "evolved into one of Ike's most valuable subordinates." The office of vice president was thereby fundamentally upgraded from a minor ceremonial post to a major role in the presidential team.[31] Nixon went well beyond the assignment, "[throwing] himself into state and local politics, making hundreds of speeches across the land. With Eisenhower uninvolved in party building, Nixon became the de facto national GOP leader."[32]

Press corps

Eisenhower frequently met with the press corps, but his performance in these meetings was widely regarded as awkward. These press conferences contributed greatly to the criticism that Eisenhower was ill-informed or merely a figurehead in his government. At times, he was able to use his reputation for unintelligible press conferences to his advantage, as it allowed him to obfuscate his position on difficult subjects.[33] On January 19, 1955 Eisenhower became the first president to conduct a televised news conference.[34] His press secretary, James Campbell Hagerty, is the only person to have served in that capacity for two full presidential terms. Historian Robert Hugh Ferrell considered him to be the best press secretary in presidential history, because he "organized the presidency for the single innovation in press relations that has itself almost changed the nature of the nation's highest office in recent decades."[35]

Judicial appointments

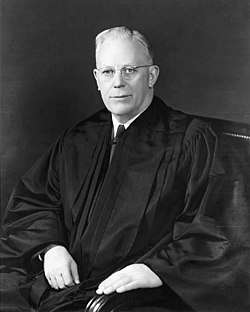

Eisenhower appointed five justices of the Supreme Court of the United States.[37] In 1953, Eisenhower nominated Governor Earl Warren to succeed Chief Justice Fred M. Vinson. Many conservative Republicans opposed Warren's nomination, but they were unable to block the appointment, and Warren's nomination was approved by the Senate in January 1954. Warren presided over a court that generated numerous liberal rulings on various topics, beginning in 1954 with the desegregation case of Brown v. Board of Education.[38] Robert H. Jackson's death in late 1954 generated another vacancy on the Supreme Court, and Eisenhower successfully nominated federal appellate judge John Marshall Harlan II to succeed Jackson. Harlan joined the conservative bloc on the bench, often supporting the position of Associate Justice Felix Frankfurter.[39]

After Sherman Minton resigned in 1956, Eisenhower nominated state supreme court justice William J. Brennan to the Supreme Court. Eisenhower hoped that the appointment of Brennan, a liberal-leaning Catholic, would boost his own re-election campaign. Opposition from Senator Joseph McCarthy and others delayed Brennan's confirmation, so Eisenhower placed Brennan on the court via a recess appointment in 1956; the Senate confirmed Brennan's nomination in early 1957. Brennan joined Warren as a leader of the court's liberal bloc. Stanley Reed's retirement in 1957 created another vacancy, and Eisenhower nominated federal appellate judge Charles Evans Whittaker, who would serve on the Supreme Court for just five years before resigning. The fifth and final Supreme Court vacancy of Eisenhower's tenure arose in 1958 due to the retirement of Harold Burton. Eisenhower successfully nominated federal appellate judge Potter Stewart to succeed Burton, and Stewart became a centrist on the court.[39] Eisenhower also appointed 45 judges to the United States Courts of Appeals, and 129 judges to the United States district courts.

Foreign affairs

Cold War

Eisenhower's 1952 candidacy was motivated in large part by his opposition to Taft's isolationist views; he did not share Taft's concerns regarding U.S. involvement in collective security and international trade, the latter of which was embodied by the 1947 General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade.[40] The Cold War dominated international politics in the 1950s. As both the United States and the Soviet Union possessed nuclear weapons, any conflict presented the risk of escalation into nuclear warfare.[41] Eisenhower continued the basic Truman administration policy of containment of Soviet expansion and the strengthening of the economies of Western Europe. Eisenhower's overall Cold War policy was described by NSC 174, which held that the rollback of Soviet influence was a long-term goal, but that the United States would not provoke war with the Soviet Union.[42] He planned for the full mobilization of the country to counter Soviet power, and emphasized making a "public effort to explain to the American people why such a militaristic mobilization of their society was needed."[43]

After Joseph Stalin died in March 1953, Georgy Malenkov took leadership of the Soviet Union. Malenkov proposed a "peaceful coexistence" with the West, and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill proposed a summit of the world leaders. Fearing that the summit would delay the rearmament of West Germany, and skeptical of Malenkov's intentions and ability to stay in power, the Eisenhower administration nixed the summit idea. In April, Eisenhower delivered his "Chance for Peace speech," in which he called for an armistice in Korea, free elections to re-unify Germany, the "full independence" of Eastern European nations, and United Nations control of atomic energy. Though well received in the West, the Soviet leadership viewed Eisenhower's speech as little more than propaganda. In 1954, a more confrontational leader, Nikita Khrushchev, took charge in the Soviet Union. Eisenhower became increasingly skeptical of the possibility of cooperation with the Soviet Union after it refused to support his Atoms for Peace proposal, which called for the creation of the International Atomic Energy Agency and the creation of nuclear power plants.[44]

National security policy

Eisenhower unveiled the New Look, his first national security policy, on October 30, 1953. It reflected his concern for balancing the Cold War military commitments of the United States with the nation's financial resources. The policy emphasized reliance on strategic nuclear weapons, rather than conventional military power, to deter both conventional and nuclear military threats.[45] The U.S. military developed a strategy of nuclear deterrence based upon the triad of land-based intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs), strategic bombers, and submarine-launched ballistic missiles (SLBMs).[46] Throughout his presidency, Eisenhower insisted on having plans to retaliate, fight, and win a nuclear war against the Soviets, although he hoped he would never feel forced to use such weapons.[47]

As the ground war in Korea ended, Eisenhower sharply reduced the reliance on expensive Army divisions. Historian Saki Dockrill argues that his long-term strategy was to promote the collective security of NATO and other American allies, strengthen the Third World against Soviet pressures, avoid another Korea, and produce a climate that would slowly and steadily weaken Soviet power and influence. Dockrill points to Eisenhower's use of multiple assets against the Soviet Union:

Eisenhower knew that the United States had many other assets that could be translated into influence over the Soviet bloc—its democratic values and institutions, its rich and competitive capitalist economy, its intelligence technology and skills in obtaining information as to the enemy's capabilities and intentions, its psychological warfare and covert operations capabilities, its negotiating skills, and its economic and military assistance to the Third World.[48]

Ballistic missiles and arms control

Eisenhower held office during period in which both the United States and the Soviet Union developed nuclear stockpiles theoretically capable of destroying not just each other, but all life on Earth. The United States had tested the first atomic bomb in 1945, and both the superpowers had tested thermonuclear weapons by the end of 1953.[49] Strategic bombers had been the delivery method of previous nuclear weapons, but Eisenhower sought to create a nuclear triad consisting of land-launched nuclear missiles, nuclear-missile-armed submarines, and strategic aircraft. Throughout the 1950s, both the United States and the Soviet Union developed intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBMs) and intermediate-range ballistic missile (IRBMs) capable of delivering nuclear warheads. Eisenhower also presided over the development of the UGM-27 Polaris missile, which was capable of being launched from submarines, and continued funding for long-range bombers like the Boeing B-52 Stratofortress.[50]

In January 1956 the United States Air Force began developing the Thor, a 1,500 miles (2,400 km) Intermediate-range ballistic missile. The program proceeded quickly, and beginning in 1958 the first of 20 Royal Air Force Thor squadrons became operational in the United Kingdom. This was the first experiment at sharing strategic nuclear weapons in NATO and led to other placements abroad of American nuclear weapons.[51] Critics at the time, led by Democratic Senator John F. Kennedy levied charges to the effect that there was a "missile gap", that is, the U.S. had fallen militarily behind the Soviets because of their lead in space. Historians now discount those allegations, although they agree that Eisenhower did not effectively respond to his critics.[52] In fact, the Soviet Union did not deploy ICBMs until after Eisenhower left office, and the U.S. retained an overall advantage in nuclear weaponry. Eisenhower was aware of the American advantage in ICBM development because of intelligence gathered by U-2 planes, which had begun flying over the Soviet Union in 1956.[53]

The administration decided the best way to minimize the proliferation of nuclear weapons was to tightly control knowledge of gas-centrifuge technology, which was essential to turn ordinary uranium into weapons-grade uranium. American diplomats by 1960 reached agreement with the German, Dutch, and British governments to limit access to the technology. The four-power understanding on gas-centrifuge secrecy would last until 1975, when scientist Abdul Qadeer Khan took the Dutch centrifuge technology to Pakistan.[54] France sought American help in developing its own nuclear program, but Eisenhower rejected these overtures due to France's instability and his distrust of French leader Charles de Gaulle.[55]

End of the Korean War

During his campaign, Eisenhower said he would go to Korea to end the Korean War, which had broken out in 1950 after North Korea invaded South Korea.[56] The U.S. had joined the war to prevent the fall of South Korea, later expanding the mission to include victory over the Communist regime in North Korea.[57] The intervention of Chinese forces in late 1950 led to a protracted stalemate around the 38th parallel north.[58]

Truman had begun peace talks in mid-1951, but the issue of North Korean and Chinese prisoners remained a sticking point. Over 40,000 prisoners from the two countries refused repatriation, but North Korea and China nonetheless demanded their return.[59] Upon taking office, Eisenhower demanded a solution, warning China that he would use nuclear weapons if the war continued.[60] South Korean leader Syngman Rhee attempted to derail peace negotiations by releasing North Korean prisoners who refused repatriation, but Rhee agreed to accept an armistice after Eisenhower threatened to withdraw all U.S. forces from Korea.[61] On July 27, 1953, the United States, North Korea, and China agreed to the Korean Armistice Agreement, ending the Korean War. Historian Edward C. Keefer says that in accepting the American demands that POWs could refuse to return to their home country, "China and North Korea still swallowed the bitter pill, probably forced down in part by the atomic ultimatum."[62] Historian William I. Hitchcock writes that the key factors in reaching the armistice were the exhaustion of North Korean forces and the desire of the Soviet leaders (who exerted pressure on China) to avoid nuclear war.[63]

The armistice led to decades of uneasy peace between North Korea and South Korea. The United States and South Korea signed a defensive treaty in October 1953, and the U.S. would continue to station thousands of soldiers in South Korea long after the end of the Korean War.[64]

Covert actions

Eisenhower, while accepting the doctrine of containment, sought to counter the Soviet Union through more active means as detailed in the State-Defense report NSC 68.[65] The Eisenhower administration and the Central Intelligence Agency used covert action to interfere with suspected communist governments abroad. An early use of covert action was against the elected Prime Minister of Iran, Mohammed Mosaddeq, resulting in the 1953 Iranian coup d'état. The CIA also instigated the 1954 Guatemalan coup d'état by the local military that overthrew President Jacobo Arbenz Guzmán, whom U.S. officials viewed as too friendly toward the Soviet Union. Critics have produced conspiracy theories about the causal factors, but according to historian Stephen M. Streeter, CIA documents show the United Fruit Company (UFCO) played no major role in Eisenhower's decision, that the Eisenhower administration did not need to be forced into the action by any lobby groups, and that Soviet influence in Guatemala was minimal.[66][67][68]

Defeating the Bricker Amendment

In January 1953, Senator John W. Bricker of Ohio re-introduced the Bricker Amendment, which would limit the president's treaty making power and ability to enter into executive agreements with foreign nations. Fears that the steady stream of post-World War II-era international treaties and executive agreements entered into by the U.S. were undermining the nation's sovereignty united isolationists, conservative Democrats, most Republicans, and numerous professional groups and civic organizations behind the amendment.[69][70] Believing that the amendment would weaken the president to such a degree that it would be impossible for the U.S. to exercise leadership on the global stage,[71] Eisenhower worked with Senate Minority Leader Lyndon B. Johnson to defeat Bricker's proposal.[72] Although the amendment started out with 56 co-sponsors, it went down to defeat in the U.S. Senate in 1954 on 42–50 vote. Later in 1954, a watered-down version of the amendment missed the required two-thirds majority in the Senate by one vote.[73] This episode proved to be the last hurrah for the isolationist Republicans, as younger conservatives increasingly turned to an internationalism based on aggressive anti-communism, typified by Senator Barry Goldwater.[74]

Europe

Eisenhower sought troop reductions in Europe by sharing of defense responsibilities with NATO allies. Europeans, however, never quite trusted the idea of nuclear deterrence and were reluctant to shift away from NATO into a proposed European Defence Community (EDC).[75] Like Truman, Eisenhower believed that the rearmament of West Germany was vital to NATO's strategic interests. The administration backed an arrangement, devised by Churchill and British Foreign Minister Anthony Eden, in which West Germany was rearmed and became a fully sovereign member of NATO in return for promises not establish atomic, biological, or chemical weapons programs. European leaders also created the Western European Union to coordinate European defense. In response to the integration of West Germany into NATO, Eastern bloc leaders established the Warsaw Pact. Austria, which had been jointly-occupied by the Soviet Union and the Western powers, regained its sovereignty with the 1955 Austrian State Treaty. As part of the arrangement that ended the occupation, Austria declared its neutrality after gaining independence.[76]

The Eisenhower administration placed a high priority on undermining Soviet influence on Eastern Europe, and escalated a propaganda war under the leadership of Charles Douglas Jackson. The United States dropped over 300,000 propaganda leaflets in Eastern Europe between 1951 and 1956, and Radio Free Europe sent broadcasts throughout the region. A 1953 uprising in East Germany briefly stoked the administration's hopes of a decline in Soviet influence, but the USSR quickly crushed the insurrection. In 1956, a major uprising broke out in Hungary. After Hungarian leader Imre Nagy promised the establishment of a multiparty democracy and withdrawal from the Warsaw Pact, Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev dispatched 60,000 soldiers into Hungary to crush the rebellion. The United States strongly condemned the military response but did not take direct action, disappointing many Hungarian revolutionaries. After the revolution, the United States shifted from encouraging revolt to seeking cultural and economic ties as a means of undermining Communist regimes.[77] Among the administration's cultural diplomacy initiatives were continuous goodwill tours by the "soldier-musician ambassadors" of the Seventh Army Symphony Orchestra.[78][79][80]

In 1953, Eisenhower opened relations with Spain under dictator Francisco Franco. Despite its undemocratic nature, Spain's strategic position in light of the Cold War and anti-communist position led Eisenhower to build a trade and military alliance with the Spanish through the Pact of Madrid. These relations brought an end to Spain's isolation after World War II, which in turn led to a Spanish economic boom known as the Spanish miracle.[81]

East Asia and Southeast Asia

After the end of World War II, the Communist Việt Minh launched an insurrection against the French-supported State of Vietnam.[82] Seeking to bolster France and prevent the fall of Vietnam to Communism, the Truman and Eisenhower administrations played a major role in financing French military operations in Vietnam.[83] In 1954, the French requested the United States to intervene in the Battle of Dien Bien Phu, which would prove to be the climactic battle of the First Indochina War. Seeking to rally public support for the intervention, Eisenhower articulated the domino theory, which held that the fall of Vietnam could lead to the fall of other countries. As France refused to commit to granting independence to Vietnam, Congress refused to approve of an intervention in Vietnam, and the French were defeated at Dien Bien Phu. At the contemporaneous Geneva Conference, Dulles convinced Chinese and Soviet leaders to pressure Viet Minh leaders to accept the temporary partition of Vietnam; the country was divided into a Communist northern half (under the leadership of Ho Chi Minh) and a non-Communist southern half (under the leadership of Ngo Dinh Diem).[82] Despite some doubts about the strength of Diem's government, the Eisenhower administration directed aid to South Vietnam in hopes of creating a bulwark against further Communist expansion.[84] With Eisenhower's approval, Diem refused to hold elections to re-unify Vietnam; those elections had been scheduled for 1956 as part of the agreement at the Geneva Conference.[85]

Eisenhower's commitment in South Vietnam was part of a broader program to contain China and the Soviet Union in East Asia. In 1954, the United States and seven other countries created the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization (SEATO), a defensive alliance dedicated to preventing the spread of Communism in Southeast Asia. In 1954, China began shelling tiny islands off the coast of Mainland China which were controlled by the Republic of China (ROC). The shelling nearly escalated to nuclear war as Eisenhower considered using nuclear weapons to prevent the invasion of Taiwan, the main island controlled by the ROC. The crisis ended when China ended the shelling and both sides agreed to diplomatic talks; a second crisis in 1958 would end in a similar fashion. During the first crisis, the United States and the ROC signed the Sino-American Mutual Defense Treaty, which committed the United States to the defense of Taiwan.[86] The CIA also supported dissidents in the 1959 Tibetan uprising, but China crushed the uprising.[87]

Middle East

The Middle East became increasingly important to U.S. foreign policy during the 1950s. After the 1953 Iranian coup, the U.S. supplanted Britain as the most influential ally of Iran. Eisenhower encouraged the creation of the Baghdad Pact, a military alliance consisting of Turkey, Iran, Iraq, and Pakistan. As it did in several other regions, the Eisenhower administration sought to establish stable, friendly, anti-Communist regimes in the Arab World. The U.S. attempted to mediate the Israeli–Palestinian conflict, but Israel's unwillingness to give up its gains from the 1948 Arab–Israeli War and Arab hostility towards Israel prevented any agreement.[88]

Suez crisis

In 1952, a revolution led by Gamal Abdel Nasser had overthrown the pro-British Egyptian government. After taking power as Prime Minister of Egypt in 1954, Nasser played the Soviet Union and the United States against each other, seeking aid from both sides. Eisenhower sought to bring Nasser into the American sphere of influence through economic aid, but Nasser's Arab nationalism and opposition to Israel served as a source of friction between the United States and Egypt. One of Nasser's main goals was the construction of the Aswan Dam, which would provide immense hydroelectric power and help irrigate much of Egypt. Eisenhower attempted to use American aid for the financing of the construction of the dam as leverage for other areas of foreign policy, but aid negotiations collapsed. In July 1956, just a week after the collapse of the aid negotiations, Nasser nationalized the British-run Suez Canal, sparking the Suez Crisis. [89]

The British strongly protested the nationalization, and formed a plan with France and Israel to capture the canal.[90] Eisenhower opposed military intervention, and he repeatedly told British Prime Minister Anthony Eden that the U.S. would not tolerate an invasion.[91] Though opposed to the nationalization of the canal, Eisenhower feared that a military intervention would disrupt global trade and alienate Middle Eastern countries from the West.[92] Israel attacked Egypt in October 1956, quickly seizing control of the Sinai Peninsula. France and Britain launched air and naval attacks after Nasser refused to renounce Egypt's nationalization of the canal. Nasser responded by sinking dozens of ships, preventing operation of the canal. Angered by the attacks, which risked sending Arab states into the arms of the Soviet Union, the Eisenhower administration proposed a cease fire and used economic pressure to force France and Britain to withdraw.[93] The incident marked the end of British and French dominance in the Middle East and opened the way for greater American involvement in the region.[94] In early 1958, Eisenhower used the threat of economic sanctions to coerce Israel into withdrawing from the Sinai Peninsula, and the Suez Canal resumed operations under the control of Egypt.[95]

Eisenhower Doctrine

In response to the power vacuum in the Middle East following the Suez Crisis, the Eisenhower administration developed a new policy designed to stabilize the region against Soviet threats or internal turmoil. Given the collapse of British prestige and the rise of Soviet interest in the region, the president informed Congress on January 5, 1957 that it was essential for the U.S. to accept new responsibilities for the security of the Middle East. Under the policy, known as the Eisenhower Doctrine, any Middle Eastern country could request American economic assistance or aid from U.S. military forces if it was being threatened by armed aggression. Though Eisenhower found it difficult to convince leading Arab states or Israel to endorse the doctrine, but he applied the new doctrine by dispensing economic aid to shore up the Kingdom of Jordan, encouraging Syria's neighbors to consider military operations against it, and sending U.S. troops into Lebanon to prevent a radical revolution from sweeping over that country.[96] The troops sent to Lebanon never saw any fighting, but the deployment marked the only time during Eisenhower's presidency when U.S. troops were sent abroad into a potential combat situation.[97]

Douglas Little argues that Washington's decision to use the military resulted from a determination to support a beleaguered, conservative pro-Western regime in Lebanon, repel Nasser's pan-Arabism, and limit Soviet influence in the oil-rich region. However, Little concludes that the unnecessary American action brought negative long-term consequences, notably the undermining of Lebanon's fragile, multi-ethnic political coalition and the alienation of Arab nationalism throughout the region.[98] To keep the pro-American King Hussein of Jordan in power, the CIA sent millions of dollars a year of subsidies. In the mid-1950s the U.S. supported allies in Lebanon, Iraq, Turkey and Saudi Arabia and sent fleets to be near Syria.[99] However, 1958 was to become a difficult year in U.S. foreign policy; in 1958 Syria and Egypt were merged into the "United Arab Republic", anti-American and anti-government revolts started occurring in Lebanon, causing the Lebanese president Chamoun to ask America for help, and the very pro-American King Feisal the 2nd of Iraq was overthrown by a group of nationalistic military officers.[100] It was quite "commonly believed that [Nasser] ... stirred up the unrest in Lebanon and, perhaps, had helped to plan the Iraqi revolution."[101]

Though U.S. aid helped Lebanon and Jordan avoid revolution, the Eisenhower doctrine enhanced Nasser's prestige as the preeminent Arab nationalist. Partly as a result of the bungled U.S. intervention in Syria, Nasser established the short-lived United Arab Republic, a political union between Egypt and Syria.[102] The U.S. also lost a sympathetic Middle Eastern government due to the 1958 Iraqi coup d'état, which saw King Faisal I replaced by General Abd al-Karim Qasim as the leader of Iraq.[103]

South Asia

The 1947 partition of British India created two new independent states, India and Pakistan. Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru pursued a non-aligned policy in the Cold War, and frequently criticized U.S. policies. Largely out of a desire to build up military strength against the more populous India, Pakistan sought close relations with the United States, joining both the Baghdad Pact and SEATO. This U.S.–Pakistan alliance alienated India from the United States, causing India to move towards the Soviet Union. In the late 1950s, the Eisenhower administration sought closer relations with India, sending aid to stem the 1957 Indian economic crisis. By the end of his administration, relations between the United States and India had moderately improved, but Pakistan remained the main U.S. ally in South Asia.[104]

Latin America

For much of his administration, Eisenhower largely continued the policy of his predecessors in Latin America, supporting U.S.-friendly governments regardless of whether they held power through authoritarian means. The Eisenhower administration expanded military aid to Latin America, and used Pan-Americanism as a tool to prevent the spread of Soviet influence. In the late 1950s, several Latin American governments fell, partly due to a recession in the United States.[105]

Cuba was particularly close to the United States, and 300,000 American tourists visited Cuba each year in the late 1950s. Cuban president Fulgencio Batista sought close ties with both the U.S. government and major U.S. companies, and American organized crime also had a strong presence in Cuba.[106] In January 1959, the Cuban Revolution ousted Batista. The new regime, led by Fidel Castro, quickly legalized the Communist Party of Cuba, sparking U.S. fears that Castro would align with the Soviet Union. When Castro visited the United States in April 1959, Eisenhower refused to meet with him, delegating the task to Nixon.[107] In the aftermath of the Cuban Revolution, the Eisenhower administration began to encourage democratic government in Latin America and increased economic aid to the region. As Castro drew closer to the Soviet Union, the U.S. broke diplomatic relations, launched a near-total embargo, and began preparations for an invasion of Cuba by Cuban exiles.[108]

U-2 Crisis

U.S. and Soviet leaders met at the 1955 Geneva Summit, the first such summit since the 1945 Potsdam Conference. No progress was made on major issues; the two sides had major differences on German policy, and the Soviets dismissed Eisenhower's "Open Skies" proposal.[109] Despite the lack of agreement on substantive issues, the conference marked the start of a minor thaw in Cold War relations.[110] Kruschev toured the United States in 1959, and he and Eisenhower conducted high-level talks regarding nuclear disarmament and the status of Berlin. Eisenhower wanted limits on nuclear weapons testing and on-site inspections of nuclear weapons, while Kruschev initially sought the total elimination of nuclear arsenals. Both wanted to limit total military spending and prevent nuclear proliferation, but Cold War tensions made negotiations difficult.[111] Towards the end of his second term, Eisenhower was determined to reach a nuclear test ban treaty as part of an overall move towards détente with the Soviet Union. Khrushchev had also become increasingly interested in reaching an accord, partly due to the growing Sino-Soviet split.[112] By 1960, the major unresolved issue was on-site inspections, as both sides sought nuclear test bans. Hopes for reaching a nuclear agreement at a May 1960 summit in Paris were derailed by the downing of an American U-2 spy plane over the Soviet Union.[111]

The Eisenhower administration, initially thinking the pilot had died in the crash, authorized the release of a cover story claiming that the plane was a "weather research aircraft" which had unintentionally strayed into Soviet airspace after the pilot had radioed "difficulties with his oxygen equipment" while flying over Turkey.[113] Further, Eisenhower said that his administration had not been spying on the Soviet Union; when the Soviets produced the pilot, Captain Francis Gary Powers, the Americans were caught misleading the public, and the incident resulted in international embarrassment for the United States.[114][115] The Senate Foreign Relations Committee held a lengthy inquiry into the U-2 incident.[116] During the Paris Summit, Eisenhower accused Khrushchev "of sabotaging this meeting, on which so much of the hopes of the world have rested",[117] Later, Eisenhower stated the summit had been ruined because of that "stupid U-2 business".[116]

International trips

Eisenhower made one international trip while president-elect, to South Korea, December 2–5, 1952; he visited Seoul and the Korean combat zone. He also made 16 international trips to 26 nations during his presidency.[118] Between August 1959 and June 1960, he undertook five major tours, travelling to Europe, Southeast Asia, South America, the Middle East, and Southern Asia. On his "Flight to Peace" Goodwill tour, in December 1959, the president visited 11 nations including five in Asia, flying 22,000 miles in 19 days.

| Dates | Country | Locations | Details | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | December 2–5, 1952 | Seoul | Visit to Korean combat zone. (Visit made as president-elect.) | |

| 2 | October 19, 1953 | Nueva Ciudad Guerrero | Dedication of Falcon Dam, with President Adolfo Ruiz Cortines.[119] | |

| 3 | November 13–15, 1953 | Ottawa | State visit. Met with Governor General Vincent Massey and Prime Minister Louis St. Laurent. Addressed Parliament. | |

| 4 | December 4–8, 1953 | Hamilton | Attended the Bermuda Conference with Prime Minister Winston Churchill and French Prime Minister Joseph Laniel. | |

| 5 | July 16–23, 1955 | Geneva | Attended the Geneva Summit with British Prime Minister Anthony Eden, French Premier Edgar Faure and Soviet Premier Nikolai Bulganin. | |

| 6 | July 21–23, 1956 | Panama City | Attended the meeting of the presidents of the American republics. | |

| 7 | March 20–24, 1957 | Hamilton | Met with Prime Minister Harold Macmillan. | |

| 8 | December 14–19, 1957 | Paris | Attended the First NATO summit. | |

| 9 | July 8–11, 1958 | Ottawa | Informal visit. Met with Governor General Vincent Massey and Prime Minister John Diefenbaker. Addressed Parliament. | |

| 10 | February 19–20, 1959 | Acapulco | Informal meeting with President Adolfo López Mateos. | |

| 11 | June 26, 1959 | Montreal | Joined Queen Elizabeth II in ceremony opening the St. Lawrence Seaway. | |

| 12 | August 26–27, 1959 | Bonn | Informal meeting with Chancellor Konrad Adenauer and President Theodor Heuss. | |

| August 27 – September 2, 1959 |

London, Balmoral, Chequers |

Informal visit. Met Prime Minister Harold Macmillan and Queen Elizabeth II. | ||

| September 2–4, 1959 | Paris | Informal meeting with President Charles de Gaulle and Italian Prime Minister Antonio Segni. Addressed North Atlantic Council. | ||

| September 4–7, 1959 | Culzean Castle | Rested before returning to the United States. | ||

| 13 | December 4–6, 1959 | Rome | Informal visit. Met with President Giovanni Gronchi. | |

| December 6, 1959 | Apostolic Palace | Audience with Pope John XXIII. | ||

| December 6–7, 1959 | Ankara | Informal visit. Met with President Celâl Bayar. | ||

| December 7–9, 1959 | Karachi | Informal visit. Met with President Ayub Khan. | ||

| December 9, 1959 | Kabul | Informal visit. Met with King Mohammed Zahir Shah. | ||

| December 9–14, 1959 | New Delhi, Agra |

Met with President Rajendra Prasad and Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru. Addressed Parliament. | ||

| December 14, 1959 | Tehran | Met with Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi. Addressed Parliament. | ||

| December 14–15, 1959 | Athens | Official visit. Met with King Paul and Prime Minister Konstantinos Karamanlis. Addressed Parliament. | ||

| December 17, 1959 | Tunis | Met with President Habib Bourguiba. | ||

| December 18–21, 1959 | Toulon, Paris |

Conference with President Charles de Gaulle, British Prime Minister Harold Macmillan and German Chancellor Konrad Adenauer. | ||

| December 21–22, 1959 | Madrid | Met with Generalissimo Francisco Franco. | ||

| December 22, 1959 | Casablanca | Met with King Mohammed V. | ||

| 14 | February 23–26, 1960 | Brasília, Rio de Janeiro, São Paulo |

Met with President Juscelino Kubitschek. Addressed Brazilian Congress. | |

| February 26–29, 1960 | Buenos Aires, Mar del Plata, San Carlos de Bariloche |

Met with President Arturo Frondizi. | ||

| February 29 – March 2, 1960 |

Santiago | Met with President Jorge Alessandri. | ||

| March 2–3, 1960 | Montevideo | Met with President Benito Nardone. Returned to the U.S. via Buenos Aires and Suriname. | ||

| 15 | May 15–19, 1960 | Paris | Conference with President Charles de Gaulle, British Prime Minister Harold Macmillan and Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev. | |

| May 19–20, 1960 | Lisbon | Official visit. Met with President Américo Tomás. | ||

| 16 | June 14–16, 1960 | Manila | State visit. Met with President Carlos P. Garcia. | |

| June 18–19, 1960 | Taipei | State visit. Met with President Chiang Kai-shek. | ||

| June 19–20, 1960 | Seoul | Met with Prime Minister Heo Jeong. Addressed the National Assembly. | ||

| 17 | October 24, 1960 | Ciudad Acuña | Informal visit. Met with President Adolfo López Mateos. |

Domestic affairs

Modern Republicanism

Eisenhower's approach to politics was described by contemporaries as "modern Republicanism," which occupied a middle ground between the liberalism of the New Deal and the conservatism of the Old Guard of the Republican Party.[120] A strong performance in the 1952 elections gave Republicans narrow majorities in both chambers of the 83rd United States Congress. Led by Taft, the conservative faction introduced numerous bills to reduce the federal government's role in American life.[121] Although Eisenhower favored some reduction of the federal government's functions and had strongly opposed President Truman's Fair Deal, he supported the continuation of Social Security and other New Deal programs that he saw as beneficial for the common good.[122] Eisenhower presided over a reduction in domestic spending and reduced the government's role in subsidizing agriculture through passage of the Agricultural Act of 1954,[123] but he did not advocate for the abolition of major New Deal programs such as Social Security or the Tennessee Valley Authority, and these programs remained in place throughout his tenure as president.[124]

Republicans lost control of Congress in the 1954 mid-term elections, and they would not regain control of either chamber until well after Eisenhower left office.[125] Eisenhower's largely nonpartisan stance enabled him to work smoothly with the Speaker of the House Sam Rayburn and Senate Majority Leader Lyndon Johnson.[126] Though liberal members of Congress like Hubert Humphrey and Paul Douglas favored expanding federal aid to education, implementing a national health insurance system, and directing federal assistance to impoverished areas, Rayburn and Johnson largely accepted Eisenhower's relatively conservative domestic policies.[127] In his own party, Eisenhower maintained strong support with moderates, but he frequently clashed with conservative members of Congress, especially over foreign policy.[128] Biographer Jean Edward Smith describes the relationship between Rayburn, Johnson, and Eisenhower:

Ike, LBJ, and "Mr. Sam" did not trust one another completely and they did not see eye to eye on every issue, but they understood one another and had no difficulty working together. Eisenhower continued to meet regularly with the Republican leadership. But his weekly sessions with Rayburn and Johnson, usually in the evening, over drinks, were far more productive. For Johnson and Rayburn, it was shrewd politics to cooperate with Ike. Eisenhower was wildly popular in the country....By supporting a Republican president against the Old Guard of his own party, the Democrats hoped to share Ike's popularity.[126]

Fiscal policy and the economy

| Year | Income | Outlays | Surplus/ Deficit |

GDP | Debt as a % of GDP[130] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1953 | 69.6 | 76.1 | -6.5 | 382.5 | 57.1 |

| 1954 | 69.7 | 70.9 | -1.2 | 387.7 | 57.9 |

| 1955 | 65.5 | 68.4 | -3.0 | 407.0 | 55.7 |

| 1956 | 74.6 | 70.6 | 3.9 | 439.0 | 50.6 |

| 1957 | 80.0 | 76.6 | 3.4 | 464.2 | 47.2 |

| 1958 | 79.6 | 82.4 | -2.8 | 474.3 | 47.7 |

| 1959 | 79.2 | 92.1 | -12.8 | 505.6 | 46.4 |

| 1960 | 92.5 | 92.2 | 0.3 | 535.1 | 44.3 |

| 1961 | 94.4 | 97.8 | -3.3 | 547.6 | 43.5 |

| Ref. | [131] | [132] | [133] | ||

Eisenhower was a fiscal conservative whose policy views were close to those of Taft— they agreed that a free enterprise economy should run itself.[134] Nonetheless, throughout Eisenhower's presidency, the top marginal tax rate was 91 percent—among the highest in American history.[135] When Republicans gained control of both houses of the Congress following the 1952 election, conservatives pressed the president to support tax cuts. Eisenhower however, gave a higher priority to balancing the budget, refusing to cut taxes "until we have in sight a program of expenditure that shows that the factors of income and outgo will be balanced." Eisenhower kept the national debt low and inflation near zero;[136] three of his eight budgets had a surplus[137]

Eisenhower built on the New Deal in a manner that embodied his thoughts on efficiency and cost-effectiveness. He sanctioned a major expansion of Social Security by a self-financed program.[138] He supported such New Deal programs as the minimum wage and public housing—he greatly expanded federal aid to education and built the Interstate Highway system primarily as defense programs (rather than a jobs program).[139] In a private letter, Eisenhower wrote:

Should any party attempt to abolish social security and eliminate labor laws and farm programs, you would not hear of that party again in our political history. There is a tiny splinter group of course, that believes you can do these things [...] Their number is negligible and they are stupid.[140]

The 1950s were a period of economic expansion in the United States, and the gross national product jumped from $355.3 billion in 1950 to $487.7 billion in 1960. Unemployment rates were also generally low, except for in 1958.[141] There were three recessions during Eisenhower's administration—July 1953 through May 1954, August 1957 through April 1958, and April 1960 through February 1961, caused by the Federal Reserve clamping down too tight on the money supply in an effort to wring out lingering wartime inflation.[136][142] Meanwhile, federal spending as a percentage of GDP fell from 20.4 to 18.4 percent—there has not been a decline of any size in federal spending as a percentage of GDP during any administration since.[137] Defense spending declined from $50.4 billion in fiscal year 1953 to $40.3 billion in fiscal year 1956, but then rose to $46.6 billion in fiscal year 1959.[143] Although defense spending declined compared to the final years of the Truman administration, defense spending under Eisenhower remained much higher than it had been prior to the Korean War and consistently made up at least ten percent of the U.S. gross domestic product.[144] The stock market performed very well while Eisenhower was in the White House, with the Dow Jones Industrial Average more than doubling (from 288 to 634),[145] and personal income increased by 45 percent.[137] Due to low-cost government loans, the introduction of the credit card, and other factors, total private debt (not including corporations) grew from $104.8 billion in 1950 to $263.3 billion in 1960.[146]

Immigration

During the early 1950s, ethnic groups in the United States mobilized to liberalize the admission of refugees from Europe who had been displaced by war and the Iron Curtain.[147] The result was the Refugee Relief Act of 1953, which permitted the admission of 214,000 immigrants to the United States from European countries between 1953 and 1956, over and above existing immigration quotas. The old quotas were quite small for Italy and Eastern Europe, but those areas received priority in the new law. The 60,000 Italians were the largest of the refugee groups.[148] Despite the arrival of the refugees, the percentage of foreign-born individuals continued to drop, as the pre-1914 arrivals died out, falling to 5.4% in 1960. The percentage of native-born individuals with at least one foreign-born parent also fell to a new low, at 13.4 percent.[149]

Responding to public outcry, primarily from California, about the perceived costs of services for illegal immigrants from Mexico, the president charged Joseph Swing, Director of the U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service, with the task of regaining control of the border. On June 17, 1954, Swing launched Operation Wetback, the roundup and deportation of undocumented immigrants in selected areas of California, Arizona, and Texas. The U.S. Border Patrol later reported that over 1.3 million people (a number viewed by many to be inflated) were deported or left the U.S. voluntarily under the threat of deportation in 1954.[148][150] Meanwhile, the number of Mexicans immigrating legally from Mexico grew rapidly during this period, from 18,454 in 1953 to 65,047 in 1956.[148]

McCarthyism

With the onset of the Cold War, the House of Representatives established the House Un-American Activities Committee to investigate alleged disloyal activities, and a new Senate committee made Senator Joseph McCarthy of Wisconsin a national leader and namesake of the anti-Communist movement.[151] Though McCarthy remained a popular figure when Eisenhower took office, his constant attacks on the State Department and the army, and his reckless disregard for due process, offended many Americans.[152] Privately, Eisenhower held McCarthy and his tactics in contempt, writing, "I despise [McCarthy's tactics], and even during the political campaign of '52 I not only stated publicly (and privately to him) that I disapproved of those methods, but I did so in his own State."[153] Eisenhower's reluctance to publicly oppose McCarthy drew criticism even from many of Eisenhower's own advisers, but the president worked incognito to weaken the popular senator from Wisconsin.[154] In early 1954, after McCarthy escalated his investigation into the army, Eisenhower moved against McCarthy by releasing a report indicating that McCarthy had pressured the army to grant special privileges to an associate, G. David Schine.[155] Eisenhower also refused to allow members of the executive branch to testify in the Army–McCarthy hearings, contributing to the collapse of those hearings.[156] Following those hearings, Senator Ralph Flanders introduced a successful measure to censure McCarthy; Senate Democrats voted unanimously for the censure, while half of the Senate Republicans voted for it. The censure ended McCarthy's status as a major player in national politics, and he died of liver failure in 1957.[157]

Though he disagreed with McCarthy on tactics, Eisenhower considered Communist infiltration to be a serious threat, and he authorized department heads to dismiss employees if there was cause to believe those employees might be disloyal to the United States. Under the direction of Dulles, the State Department purged over 500 employees.[158] With Eisenhower's approval, the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) stepped up domestic surveillance efforts, establishing COINTELPRO in 1956.[159] In 1957, the Supreme Court handed down a series of decisions that bolstered constitutional protections and curbed the power of the Smith Act, resulting in a decline of prosecutions of suspected Communists during the late 1950s.[160]

In 1953, Eisenhower refused to commute the death sentences of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, two U.S. citizens who were convicted in 1951 of providing nuclear secrets to the Soviet Union. This provoked a worldwide outburst of picketing and demonstrations in favor of the Rosenbergs, along with editorials in otherwise pro-American newspapers and a plea for clemency from the Pope. Eisenhower, supported by public opinion and the media at home, ignored the overseas demand.[161] The Rosenbergs were executed via electric chair in July 1953.

Civil rights

First term

In the 1950s, African Americans in the South faced mass disenfranchisement and racially segregated schools, bathrooms, and drinking fountains. Even outside of the South, African Americans faced employment discrimination, housing discrimination, and high rates of poverty and unemployment.[162] Civil rights had emerged as a major national and global issue in the 1940s, partly due to the negative example set by Nazi Germany.[163] Segregation damaged relations with African countries, undercut U.S. calls for decolonization, and emerged as a major theme in Soviet propaganda.[164] Truman had begun the process of desegregating the Armed Forces in 1948, but actual implementation had been slow. Southern Democrats strongly resisted integration, and many Southern leaders had endorsed Eisenhower in 1952 after the latter indicated his opposition to federal efforts to compel integration.[165]

Upon taking office, Eisenhower moved quickly to end resistance to desegregation of the military by using government control of spending to compel compliance from military officials. "Wherever federal funds are expended," he told reporters in March, "I do not see how any American can justify a discrimination in the expenditure of those funds." Later, when Secretary of the Navy Robert B. Anderson stated in a report, "The Navy must recognize the customs and usages prevailing in certain geographic areas of our country which the Navy had no part in creating," Eisenhower responded, "We have not taken and we shall not take a single backward step. There must be no second class citizens in this country."[166] Eisenhower also sought to end discrimination in federal hiring and in Washington, D.C. facilities.[167] Despite these actions, Eisenhower continued to resist becoming involved in the expansion of voting rights, the desegregation of public education, or the eradication of employment discrimination.[163] E. Frederic Morrow, the lone black member of the White House staff, met only occasionally with Eisenhower, and was left with the impression that Eisenhower had little interest in understanding the lives of African Americans.[168]

On May 17, 1954, the Supreme Court handed down its landmark ruling in Brown v. Board of Education, declaring state laws establishing separate public schools for black and white students to be unconstitutional. Privately, Eisenhower disapproved of the Supreme Court's holding, stating that he believed it "set back progress in the South at least fifteen years."[169] The president's public response was a frosty, "The Supreme Court has spoken and I am sworn to uphold the constitutional processes in this country; and I will obey." Over the succeeding six years of his presidency, author Robert Caro notes, Eisenhower would never "publicly support the ruling; not once would he say that Brown was morally right".[170] His silence left civil rights leaders with the impression that Ike didn't care much about the day-to-day plight of blacks in America, and it served as a source of encouragement for segregationists vowing to resist school desegregation.[137] These segregationists, including the Ku Klux Klan, conducted a campaign of "massive resistance," violently opposing those who sought to desegregate public education in the South. In 1956, most of Southern members of Congress signed the Southern Manifesto, which called for the overturning of Brown.[171]

Second term

As Southern leaders continued to resist desegregation, Eisenhower sought to defuse calls for stronger federal action by introducing a civil rights bill. The bill included provisions designed to increase the protection of African American voting rights; approximately 80% of African Americans were disenfranchised in the mid-1950s.[172] The civil rights bill passed the House relatively easily, but faced strong opposition in the Senate from Southerners, and the bill passed only after many of its original provisions were removed. Though some black leaders urged him to reject the watered-down bill as inadequate, Eisenhower signed the Civil Rights Act of 1957 into law. It was the first federal law designed to protect African Americans since the end of Reconstruction.[173] The act created the United States Commission on Civil Rights and established a civil rights division in the Justice Department, but it also required that defendants in voting rights cases receive a jury trial. The inclusion of the last provision made the act ineffectual, since white jurors in the South would not vote to convict defendants for interfering with the voting rights of African Americans.[174]

Eisenhower hoped that the passage of the Civil Rights Act would, at least temporarily, remove the issue of civil rights from the forefront of national politics, but events in Arkansas would force him into action.[175] The school board of Little Rock, Arkansas created a federal court-approved plan for desegregation, with the program to begin implementation at Little Rock Central High School. Fearing that desegregation would complicate his re-election efforts, Governor Orval Faubus mobilized the National Guard to prevent nine black students, known as the "Little Rock Nine," from entering Central High. Though Eisenhower had not fully embraced the cause of civil rights, he was determined to uphold federal authority and to prevent an incident that could embarrass the United States on the international stage. Eisenhower convinced Faubus to withdraw the National Guard, but a mob prevented the black students from attending Central High. In response, Eisenhower sent the army into Little Rock, and the army ensured that the Little Rock Nine could attend Central High. Faubus derided Eisenhower's actions, claiming that Little Rock had become "occupied territory," and in 1958 he temporarily shut down Little Rock high schools.[176]

Towards the end of his second term, Eisenhower proposed another civil rights bill designed to help protect voting rights, but Congress once again passed a bill with weaker provisions than Eisenhower had requested. Eisenhower signed the bill into law as the Civil Rights Act of 1960.[177] By 1960, 6.4% of Southern black students attended integrated schools and thousands of black voters had registered to vote, but millions of African Americans remained disenfranchised.[178]

Lavender Scare

Eisenhower's administration contributed to the McCarthyist Lavender Scare[179] with President Eisenhower issuing his Executive Order 10450 in 1953.[180] During Eisenhower's presidency, thousands of lesbian and gay applicants were barred from federal employment and over 5,000 federal employees were fired under suspicions of being homosexual.[181][182] From 1947 to 1961, the number of firings based on sexual orientation were far greater than those for membership in the Communist party,[181] and government officials intentionally campaigned to make "homosexual" synonymous with "Communist traitor" such that LGBT people were treated as a national security threat stemming from the belief they were susceptible to blackmail and exploitation.[183]

Interstate highway system

One of Eisenhower's enduring achievements was the Interstate Highway System, which Congress authorized through the Federal Aid Highway Act of 1956. Historian James T. Patterson describes the act as the "only important law" passed during Eisenhower's first term aside from the expansion of Social Security.[184] In 1954, Eisenhower appointed General Lucius D. Clay to head a committee charged with proposing an interstate highway system plan.[185] The president's support for the project was influenced by his experiences as a young army officer crossing the country as part of the 1919 Army Convoy.[186] Summing up motivations for the construction of such a system, Clay stated,

It was evident we needed better highways. We needed them for safety, to accommodate more automobiles. We needed them for defense purposes, if that should ever be necessary. And we needed them for the economy. Not just as a public works measure, but for future growth.[187][188]

Clay's committee proposed a 10-year, $100 billion program, which would build 40,000 miles of divided highways linking all American cities with a population of greater than 50,000. Eisenhower initially preferred a system consisting of toll roads, but Clay convinced Eisenhower that toll roads were not feasible outside of the highly populated coastal regions. In February 1955, Eisenhower forwarded Clay's proposal to Congress. The bill quickly won approval in the Senate, but House Democrats objected to the use of public bonds as the means to finance construction. Eisenhower and the House Democrats agreed to instead finance the system through the Highway Trust Fund, which itself would be funded by a gasoline tax.[189] Another major infrastructure project, the Saint Lawrence Seaway, was also completed during Eisenhower's presidency.[190]

In long-term perspective the interstate highway system was a remarkable success, that has done much to sustain Eisenhower's positive reputation. Although there have been objections to the negative impact of clearing neighborhoods in cities, the system has been well received. The railroad system for passengers and freight declined sharply, but the trucking expanded dramatically and the cost of shipping and travel fell sharply. Suburbanization became possible, with the rapid growth of easily accessible, larger, cheaper housing than was available in the overcrowded central cities. Tourism dramatically expanded as well, creating a demand for more service stations, motels, restaurants and visitor attractions. There was much more long-distance movement to the Sunbelt for winter vacations, or for permanent relocation, with convenient access to visits to relatives back home. In rural areas, towns and small cities off the grid lost out as shoppers followed the interstate, and new factories were located near them.[191]

Space program and education

In 1955, in separate announcements four days apart, both the United States and the Soviet Union publicly announced that they would launch artificial Earth satellites within the next few years. The July 29, announcement from the White House stated that the U.S. would launch "small Earth circling satellites" between July 1, 1957, and December 31, 1958, as part of the American contribution to the International Geophysical Year.[192] Americans were astonished when October 4, 1957, the Soviet Union launched its Sputnik 1 satellite into orbit[193] Three months later, a nationally televised test of the American Vanguard TV3 missile failed in an embarrassing fashion; the missile was facetiously referred to as "Flopnik" and "Stay-putnik."[194]

To many, the success of the Soviet satellite program suggested that the Soviet Union had made a substantial leap forward in technology that posed a serious threat to U.S. national security. While Eisenhower initially downplayed the gravity of the Soviet launch, public fear and anxiety about the perceived technological gap grew. Americans rushed to build nuclear bomb shelters, while the Soviet Union boasted about its new superiority as a world power.[195] The president was, as British prime minister Harold Macmillan observed during a June 1958 visit to the U.S., "under severe attack for the first time" in his presidency.[196] Economist Bernard Baruch wrote in an open letter to the New York Herald Tribune titled "The Lessons of Defeat": "While we devote our industrial and technological power to producing new model automobiles and more gadgets, the Soviet Union is conquering space. ... It is Russia, not the United States, who has had the imagination to hitch its wagon to the stars and the skill to reach for the moon and all but grasp it. America is worried. It should be."[197]

The launch spurred a series of federal government initiatives ranging from defense to education. Renewed emphasis was placed on the Explorers program (which had earlier been supplanted by Project Vanguard) to launch an American satellite into orbit; this was accomplished on January 31, 1958 with the successful launch of Explorer 1.[198] In February 1958, Eisenhower authorized formation of the Advanced Research Projects Agency, later renamed the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), within the Department of Defense to develop emerging technologies for the U.S. military. The new agency's first major project was the Corona satellite, which was designed to replace the U-2 spy plane as a source of photographic evidence.[199] On July 29, 1958, he signed the National Aeronautics and Space Act, which established NASA as a civilian space agency.[200] NASA took over the space technology research started by DARPA, as well as the air force's manned satellite program, Man In Space Soonest, which was renamed as Project Mercury.[201] The project's first seven astronauts were announced on April 9, 1959.[202]

In September 1958, the president signed into law the National Defense Education Act, a four-year program that poured billions of dollars into the U.S. education system. In 1953 the government spent $153 million, and colleges took $10 million of that funding; however, by 1960 the combined funding grew almost six-fold as a result.[203] Meanwhile, during the late 1950s and into the 1960s, NASA, the Department of Defense, and various private sector corporations developed multiple communications satellite research and development programs.[204]

Labor unions

Union membership peaked in the mid-1950s, when unions consisted of about one-quarter of the total work force. The Congress of Industrial Organizations and the American Federation of Labor merged in 1955 to form the AFL–CIO, the largest federation of unions in the United States. Unlike some of his predecessors, AFL–CIO leader George Meany did not emphasize organizing unskilled workers and workers in the South.[205] During the late 1940s and the 1950s, both the business community and local Republicans sought to weaken unions, partly because they played a major role in funding and campaigning for Democratic candidates.[206] The Eisenhower administration also worked to consolidate the anti-union potential inherent in Taft–Hartley Act of 1947.[207] Republicans sought to delegitimize unions by focusing on their shady activities, and the Justice Department, the Labor Department, and Congress all conducted investigations of criminal activity and racketeering in high-profile labor unions, especially the Teamsters Union. A select Senate committee, the McClellan Committee, was created in January 1957, and its hearings targeted Teamsters Union president James R. Hoffa as a public enemy.[208] Public opinion polls showed growing distrust toward unions, and especially union leaders—or "labor bosses," as Republicans called them. The bipartisan Conservative Coalition, with the support of liberals such as the Kennedy brothers, won new congressional restrictions on organized labor in the 1959 Landrum-Griffin Act. The main impact of that act was to force more democracy on the previously authoritarian union hierarchies.[209][210] However, in the 1958 elections, the unions fought back against state right-to-work laws and defeated many conservative Republicans.[211][212]

Mid-term elections of 1958

The economy began to decline in mid-1957 and reached its nadir in early 1958. The Recession of 1958 was the worst economic downturn of Eisenhower's tenure, as the unemployment rate reached a high of 7.5%. The poor economy, Sputnik, the federal intervention in Little Rock, and a contentious budget battle all sapped Eisenhower's popularity, with Gallup polling showing that his approval rating dropped from 79 percent in February 1957 to 52 percent in March 1958.[213] A controversy broke out in mid-1958 after a House subcommittee discovered that White House Chief of Staff Sherman Adams had accepted an expensive gift from Bernard Goldfine, textile manufacturer under investigation by the Federal Trade Commission (FTC). Adams denied the accusation that he had interfered with the FTC investigation on Goldfine's behalf, but Eisenhower forced him to resign in September 1958.[214] As the 1958 mid-term elections approached, the Democrats attacked Eisenhower over the Space Race, the controversy relating to Adams, and other issues, but the biggest issue of the campaign was the economy, which had not yet fully recovered. Republicans suffered major defeats in the elections, as Democrats picked up over forty seats in the House and over ten seats in the Senate. Several leading Republicans, including Bricker and Senate Minority Leader William Knowland, lost their re-election campaigns.[215]

Twenty-third Amendment