James A. Garfield

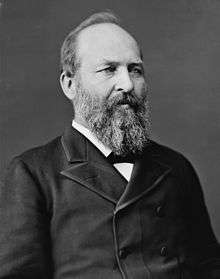

James Abram Garfield (November 19, 1831 – September 19, 1881) was the 20th president of the United States, serving from March 4, 1881, until his death by assassination six and a half months later. He is the only sitting member of the United States House of Representatives to be elected to the presidency.[1]

James A. Garfield | |

|---|---|

| |

| 20th President of the United States | |

| In office March 4, 1881 – September 19, 1881 | |

| Vice President | Chester A. Arthur |

| Preceded by | Rutherford B. Hayes |

| Succeeded by | Chester A. Arthur |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Ohio's 19th district | |

| In office March 4, 1863 – November 8, 1880 | |

| Preceded by | Albert G. Riddle |

| Succeeded by | Ezra B. Taylor |

| Chair of the House Appropriations Committee | |

| In office March 4, 1871 – March 4, 1875 | |

| Preceded by | Henry L. Dawes |

| Succeeded by | Samuel J. Randall |

| Personal details | |

| Born | James Abram Garfield November 19, 1831 Moreland Hills, Ohio, U.S. |

| Died | September 19, 1881 (aged 49) Elberon, New Jersey, U.S. |

| Cause of death | Assassination |

| Resting place | James A. Garfield Memorial |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouse(s) | |

| Children | 7, including Hal, James, and Abram |

| Parents |

|

| Education | |

| Signature | |

| Military service | |

| Branch/service | |

| Years of service | 1861–1863 |

| Rank | |

| Commands |

|

| Battles/wars | |

Garfield entered politics as a Republican in 1857. He served as a member of the Ohio State Senate from 1859 to 1861. Garfield opposed Confederate secession, served as a major general in the Union Army during the American Civil War, and fought in the battles of Middle Creek, Shiloh, and Chickamauga. He was first elected to Congress in 1862 to represent Ohio's 19th district. Throughout Garfield's congressional service after the war, he firmly supported the gold standard and gained a reputation as a skilled orator. He initially agreed with Radical Republican views on Reconstruction, but later favored a moderate approach to civil rights enforcement for freedmen.

At the 1880 Republican National Convention, delegates chose Garfield, who had not sought the White House, as a compromise presidential nominee on the 36th ballot. In the 1880 presidential election, he conducted a low-key front porch campaign and narrowly defeated Democrat Winfield Scott Hancock. Garfield's accomplishments as president included a resurgence of presidential authority against senatorial courtesy in executive appointments, purging corruption in the Post Office, and appointing a U.S. Supreme Court justice. He enhanced the powers of the presidency when he defied the powerful New York senator Roscoe Conkling by appointing William H. Robertson to the lucrative post of Collector of the Port of New York, starting a fracas that ended with Robertson's confirmation and Conkling's resignation from the Senate. Garfield advocated agricultural technology, an educated electorate, and civil rights for African Americans. He also proposed substantial civil service reforms, which were passed by Congress in 1883 and signed into law by his successor, Chester A. Arthur, as the Pendleton Civil Service Reform Act.

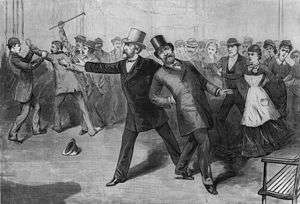

On July 2, 1881, Charles J. Guiteau, a disappointed and delusional office seeker, shot Garfield at the Baltimore and Potomac Railroad Station in Washington D.C. The wound was not immediately fatal, but he died on September 19, 1881, from infections caused by his doctors. Guiteau was executed for Garfield's murder in June 1882.

Childhood and early life

James Garfield was born the youngest of five children on November 19, 1831, in a log cabin in Orange Township, now Moreland Hills, Ohio. Orange Township had been in the Western Reserve until 1800, and like many who settled there, Garfield's ancestors were from New England, his ancestor Edward Garfield immigrating from Hillmorton, Warwickshire, England, to Massachusetts around 1630. James's father Abram had been born in Worcester, New York, and came to Ohio to woo his childhood sweetheart, Mehitabel Ballou, only to find her married. He instead wed her sister Eliza, who had been born in New Hampshire. James was named for an older brother who died in infancy.[2]

In early 1833, Abram and Eliza Garfield joined the Church of Christ, a decision that shaped their youngest son's life.[3] Abram died later that year; James was raised in poverty in a household led by the strong-willed Eliza.[4] He was her favorite child, and the two remained close for the rest of his life.[5] Eliza Garfield remarried in 1842, but soon left her second husband, Warren Belden (or Alfred Belden), and a then scandalous divorce was awarded in 1850. James took his mother's side and when Belden died in 1880, noted it in his diary with satisfaction.[6] Garfield enjoyed his mother's stories about his ancestry, especially his Welsh great-great-grandfathers and his ancestor who served as a knight of Caerffili Castle.[7]

Poor and fatherless, Garfield was mocked by his fellow boys, and was very sensitive to slights throughout his life. He escaped by reading all the books he could find.[6] He left home at age 16 in 1847. Rejected by the only ship in port in Cleveland, Garfield instead found work on a canal boat, responsible for managing the mules that pulled it.[8] This labor was used to good effect by Horatio Alger, who wrote Garfield's campaign biography in 1880.[9]

After six weeks, illness forced Garfield to return home and, during his recuperation, his mother and a local education official got him to promise to postpone his return to the canals for a year and go to school. Accordingly, in 1848, he began at Geauga Seminary, in nearby Chester Township, Geauga County, Ohio.[10] Garfield later said of his childhood, "I lament that I was born to poverty, and in this chaos of childhood, seventeen years passed before I caught any inspiration ... a precious 17 years when a boy with a father and some wealth might have become fixed in manly ways."[11]

Education, marriage and early career

At Geauga Academy, which he attended from 1848 to 1850, Garfield learned academic subjects for which he had not previously had time. He excelled as a student, and was especially interested in languages and elocution. He began to appreciate the power a speaker had over an audience, writing that the speaker's platform "creates some excitement. I love agitation and investigation and glory in defending unpopular truth against popular error."[12] Geauga was coeducational, and Garfield was attracted to one of his fellow students, Lucretia Rudolph, whom he later married.[13] To support himself at Geauga, he worked as a carpenter's assistant and a teacher.[14] The need to go from town to town to find work as a teacher disgusted Garfield, and he thereafter developed a dislike of what he called "place-seeking", which became, he said, "the law of my life."[15] In later years, he astounded his friends by letting positions pass that could have been his with a little politicking.[15] Garfield had attended church more to please his mother than to worship God, but in his late teens underwent a religious awakening, and attended many camp meetings, at one of which he was born again on March 4, 1850, baptized into Christ by being submerged in the icy waters of the Chagrin River.[16][lower-alpha 1]

After leaving Geauga, Garfield worked for a year at various jobs, including teaching.[18] Finding that some New Englanders worked their way through college, Garfield determined to do the same, and sought a school that could prepare him for the entrance examinations. From 1851 to 1854, he attended the Western Reserve Eclectic Institute (later named Hiram College) in Hiram, Ohio, a school run by the Disciples. While there, he was most interested in the study of Greek and Latin, but was inclined to learn about and discuss any new thing he encountered.[19] Securing a position on entry as janitor, he was hired to teach while still a student.[20] Lucretia Rudolph also enrolled at the Institute, and Garfield wooed her while teaching her Greek.[21] He developed a regular preaching circuit at neighboring churches, in some cases earning a gold dollar per service. By 1854, Garfield had learned all the Institute could teach him and was a full-time teacher.[22] Garfield then enrolled at Williams College in Williamstown, Massachusetts, as a third-year student, given credit for two years' study at the Institute after passing a cursory examination. Garfield was impressed with the college president, Mark Hopkins, who had responded warmly to Garfield's letter inquiring about admission. He said of Hopkins, "The ideal college is Mark Hopkins on one end of a log with a student on the other."[23] Hopkins later said of Garfield in his student days, "There was a large general capacity applicable to any subject. There was no pretense of genius, or alternation of spasmodic effort, but a satisfactory accomplishment in all directions."[24] After his first term, Garfield was hired to teach penmanship to the students of nearby Pownal, Vermont, a post previously held by Chester A. Arthur.[24]

Garfield graduated Phi Beta Kappa[25] from Williams in August 1856 as salutatorian, giving an address at the commencement. His biographer Ira Rutkow writes that Garfield's years at Williams gave Garfield the opportunity to know and respect those of different social backgrounds, and that despite his origin as an unsophisticated Westerner, he was liked and respected by socially conscious New Englanders. "In short", Rutkow writes, "Garfield had an extensive and positive first experience with the world outside the Western Reserve of Ohio."[24]

On his return to Ohio, the degree from a prestigious Eastern school made Garfield a man of distinction. He returned to Hiram to teach at the Institute, and in 1857 was made its president. He did not see education as a field that would realize his full potential. At Williams, he had become more politically aware in the school's intensely anti-slavery atmosphere, and began to consider politics as a career.[26] In 1858, he married Lucretia; they had seven children, five of whom survived infancy.[27] Soon after the wedding, he formally entered his name to read law (1859) at the office of attorney Albert Gallatin Riddle[28] a Cleveland firm, although he did his studying in Hiram.[29] He was admitted to the bar in 1861.[30]

Local Republican leaders invited Garfield to enter politics upon the death of Cyrus Prentiss, the presumptive nominee for the local state senate seat. He was nominated at the party convention on the sixth ballot, and was elected, serving until 1861.[31] Garfield's major effort in the state senate was a bill providing for Ohio's first geological survey to measure its mineral resources, but it failed.[32]

Civil War

After Abraham Lincoln's election as president, several Southern states announced their secession from the Union to form a new government, the Confederate States of America. Garfield read military texts while anxiously awaiting the war effort, which he regarded as a holy crusade against the Slave Power.[33] In April 1861, the rebels bombarded Fort Sumter, one of South's last federal outposts, beginning the Civil War. Although he had no military training, Garfield knew that his place was in the Union Army.[33]

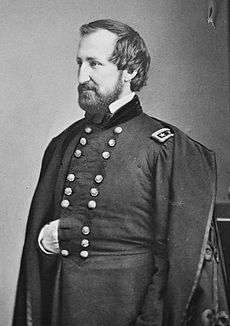

At Governor William Dennison's request, Garfield deferred his military ambitions to remain in the legislature, where he helped appropriate the funds to raise and equip Ohio's volunteer regiments.[34] Afterward, the legislature adjourned and Garfield spent the spring and early summer on a speaking tour of northeastern Ohio, encouraging enlistment in the new regiments.[34] Following a trip to Illinois to purchase muskets, Garfield returned to Ohio and, in August 1861, received a commission as a colonel in the 42nd Ohio Infantry regiment.[35] The 42nd Ohio existed only on paper, so Garfield's first task was to fill its ranks. He did so quickly, recruiting many of his neighbors and former students.[35] The regiment traveled to Camp Chase, outside Columbus, Ohio, to complete training.[35] In December, Garfield was ordered to bring the 42nd to Kentucky, where they joined the Army of the Ohio under Brigadier General Don Carlos Buell.[36]

Buell's command

Buell quickly assigned Garfield the task of driving Confederate forces out of eastern Kentucky, giving him the 18th Brigade for the campaign, which, besides his own 42nd, included the 40th Ohio Infantry, two Kentucky infantry regiments and two cavalry units.[37] They departed Catlettsburg, Kentucky, in mid-December, advancing through the valley of the Big Sandy River.[37] The march was uneventful until Union forces reached Paintsville, Kentucky, on January 6, 1862, where Garfield's cavalry engaged the rebels at Jenny's Creek.[38] Confederate troops under Brigadier General Humphrey Marshall held the town in numbers roughly equal to Garfield's own, but Garfield positioned his troops so as to deceive Marshall into believing the rebels were outnumbered.[38] Marshall ordered his troops to withdraw to the forks of Middle Creek, on the road to Virginia; Garfield ordered his troops to pursue them.[39] They attacked the rebel positions on January 9, 1862, in the Battle of Middle Creek, the only pitched battle Garfield personally commanded.[40] At the fighting's end, the Confederates withdrew from the field, and Garfield sent his troops to Prestonsburg to reprovision.[41]

In recognition of his success, Garfield was promoted to brigadier general.[42] After Marshall's retreat, Garfield's command was the sole remaining Union force in eastern Kentucky, and he announced that any men who had fought for the Confederacy would be granted amnesty if they returned to their homes and lived peaceably and remained loyal to the Union.[43] The proclamation was surprisingly lenient, as Garfield now believed the war was a crusade for eradication of slavery.[43] Following a brief skirmish at Pound Gap, the last rebel units in the area were outflanked and retreated to Virginia.[44]

Garfield's promotion gave him command of the 20th Brigade of the Army of the Ohio, which was ordered in early 1862 to join Major General Ulysses S. Grant's forces as they advanced on Corinth, Mississippi.[45] Before the 20th Brigade arrived, however, Confederate forces under General Albert Sidney Johnston surprised Grant's men in their camps, driving them back.[46] Garfield's troops got word of the battle and advanced quickly, joining the rest of the army on the second day to drive the Confederates back across the field and into retreat.[47] The action, later known as the Battle of Shiloh, was the bloodiest of the war to date; Garfield was exposed to fire for much of the day, but emerged uninjured.[47] Major General Henry W. Halleck, Grant's superior, took charge of the combined armies and advanced ponderously toward Corinth; when they arrived, the Confederates had fled.[48]

That summer Garfield suffered from jaundice and significant weight loss.[lower-alpha 2][50] He was forced to return home, where his wife nursed him back to health.[50] While he was home, Garfield's friends worked to gain him the Republican nomination for Congress, but he refused to campaign with the delegates.[51] He returned to military duty that autumn and went to Washington to await his next assignment.[52] During this period of idleness, a rumor of an extramarital affair caused friction in the Garfields' marriage until Lucretia eventually chose to overlook it.[53] Garfield repeatedly received tentative assignments that were quickly withdrawn, to his frustration.[54] In the meantime, he served on the court-martial of Fitz John Porter for his tardiness at the Second Battle of Bull Run.[55] He was convinced of Porter's guilt, and voted with his fellow generals to convict.[55] The trial lasted almost two months, from November 1862 to January 1863, and by its end, Garfield had procured an assignment as Chief of Staff to Major General William S. Rosecrans.[56]

Chief of staff for Rosecrans

Generals' chiefs of staff were usually more junior officers, but Garfield's influence with Rosecrans was greater than usual, with duties extending beyond communication of orders to actual management of his Army of the Cumberland.[57] Rosecrans had a voracious appetite for conversation, especially when unable to sleep; in Garfield, he found "the first well read person in the Army" and the ideal candidate for discussions that ran deep into the night.[58] The two became close despite Garfield's being 12 years Rosecrans's junior, and they discussed everything, especially religion; Rosecrans, who had converted from Methodism to Roman Catholicism, softened Garfield's view of his faith.[59] Garfield recommended that Rosecrans replace wing commanders Alexander McCook and Thomas Crittenden, whom he believed ineffective, but Rosecrans ignored the suggestion.[60] With Rosecrans, Garfield devised the Tullahoma Campaign to pursue and trap Confederate General Braxton Bragg in Tullahoma. After initial Union success, Bragg retreated toward Chattanooga, where Rosecrans stalled and requested more troops and supplies.[61] Garfield argued for an immediate advance, in line with demands from Halleck and Lincoln.[61] After a council of war and lengthy deliberations, Rosecrans agreed to attack.[62]

At the ensuing Battle of Chickamauga on September 19 and 20, 1863, confusion among the wing commanders over Rosecrans's orders created a gap in the lines, resulting in a rout of the right flank. Rosecrans concluded that the battle was lost and fell back on Chattanooga to establish a defensive line.[63] Garfield, however, thought that part of the army had held and, with Rosecrans's approval, headed across Missionary Ridge to survey the scene. Garfield's hunch was correct.[63] His ride became legendary, while Rosecrans's error reignited criticism about his leadership.[63] While Rosecrans's army had avoided disaster, they were stranded in Chattanooga, surrounded by Bragg's army. Garfield sent a telegram to Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton alerting Washington to the need for reinforcements to avoid annihilation, and Lincoln and Halleck delivered 20,000 troops by rail within nine days.[64] In the meantime, Grant was promoted to command of the western armies, and quickly replaced Rosecrans with George H. Thomas.[65] Garfield was ordered to report to Washington, where he was promoted to major general, a commission he resigned before taking a seat in the House of Representatives.[66] According to historian Jean Edward Smith, Grant and Garfield had a "guarded relationship", since Grant promoted Thomas, rather than Garfield, to command of the Army of the Cumberland after Rosecrans's dismissal.[67]

Congressional career

Election in 1862; Civil War years

.jpg)

While serving in the Army in early 1862, Garfield was approached by friends about running for Congress from Ohio's newly redrawn, heavily Republican 19th district. He was worried that he and other state-appointed generals would get obscure assignments, and running for Congress would allow him to resume his political career. The fact that the new Congress would not hold its first regular session until December 1863[lower-alpha 3] allowed him to continue his war service for a time. Home on medical leave, he refused to campaign for the nomination, leaving that to political managers who secured it at the local convention in September 1862 on the eighth ballot. In October, he defeated D.B. Woods by a two-to-one margin in the general election for a seat in the 38th Congress.[68]

Soon after his nomination, Garfield was ordered to report to War Secretary Edwin Stanton in Washington to discuss his military future. There, he met Treasury Secretary Salmon P. Chase, who befriended him, seeing him as a younger version of himself. The two agreed politically, and both were part of the Radical wing of the Republican Party.[69] Once he took his seat in December 1863, Garfield was frustrated that Lincoln seemed reluctant to press the South hard. Many radicals, led in the House by Pennsylvania's Thaddeus Stevens, wanted rebel-owned lands confiscated, but Lincoln threatened to veto any bill to do that on a widespread basis. In debate on the House floor, Garfield supported such legislation and, discussing England's Glorious Revolution, hinted that Lincoln might be thrown out of office for resisting it.[70] Garfield had supported Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation, and marveled that it was a "strange phenomenon in the world's history, when a second-rate Illinois lawyer is the instrument to utter words which shall form an epoch memorable in all future ages."[71]

Garfield not only favored abolition of slavery, but believed that the leaders of the rebellion had forfeited their constitutional rights. He supported the confiscation of southern plantations and even exile or execution of rebellion leaders as a means to ensure a permanent end to slavery.[72] Garfield felt Congress was obliged "to determine what legislation is necessary to secure equal justice to all loyal persons, without regard to color."[73] He was more supportive of Lincoln when Lincoln took action against slavery.[74] Early in his tenure, he differed from his party on several issues; his was the solitary Republican vote to terminate the use of bounties in recruiting. Some financially able recruits had used the bounty system to buy their way out of service (called commutation), which Garfield considered reprehensible.[75] Garfield gave a speech pointing out the flaws in the existing conscription law: that of 300,000 called upon to enlist, barely 10,000 had, the remainder claiming exemption or providing money or a substitute. Lincoln appeared before the Military Affairs committee on which Garfield served, demanding a more effective bill; even if it cost him reelection, Lincoln was confident he could win the war before his term expired.[76] After many false starts, Garfield, with Lincoln's support, procured the passage of a conscription bill that excluded commutation.[77]

Under Chase's influence, Garfield became a staunch proponent of a dollar backed by a gold standard, and was therefore a strong opponent of the "greenback"; he regretted very much, but understood, the necessity for suspension of payment in gold or silver during the Civil War.[78] Garfield voted with the Radical Republicans in passing the Wade–Davis Bill, designed to give Congress more authority over Reconstruction, but it was defeated by Lincoln's pocket veto.[79]

Garfield did not consider Lincoln particularly worthy of reelection, but there seemed to be no viable alternative. "He will probably be the man, though I think we could do better", he said.[71] Garfield attended the party convention and promoted Rosecrans as Lincoln's running mate, but delegates chose Military Governor of Tennessee Andrew Johnson.[80] Lincoln and Garfield were reelected.[81] By then, Chase had left the Cabinet and had been appointed Chief Justice, and his relations with Garfield became more distant.[82]

Garfield took up the practice of law in 1865 as a means to improve his personal finances. His efforts took him to Wall Street where, the day after Lincoln's assassination, a riotous crowd led him into an impromptu speech to calm it: "Fellow citizens! Clouds and darkness are round about Him! His pavilion is dark waters and thick clouds of the skies! Justice and judgment are the establishment of His throne! Mercy and truth shall go before His face! Fellow citizens! God reigns, and the Government at Washington still lives!"[83] The speech, with no mention or praise of Lincoln, was, according to Garfield biographer Robert G. Caldwell, "quite as significant for what it did not contain as for what it did."[84] In the following years, Garfield had more praise for Lincoln; a year after Lincoln's death, Garfield said, "Greatest among all these developments were the character and fame of Abraham Lincoln," and in 1878 he called Lincoln "one of the few great rulers whose wisdom increased with his power."[85]

Reconstruction

Garfield was as firm a supporter of black suffrage as he had been of abolition, though he admitted that the idea of African Americans as whites' political equals gave him "a strong feeling of repugnance."[86][lower-alpha 4] President Johnson sought the rapid restoration of the Southern states during the months between his accession and the meeting of Congress in December 1865; Garfield hesitantly supported this policy as an experiment. Johnson, an old friend, sought Garfield's backing, and their conversations led Garfield to assume that Johnson's differences with Congress were not large. When Congress assembled in December (to Johnson's chagrin without the elected representatives of the Southern states, who were excluded), Garfield urged conciliation on his colleagues, although he feared that Johnson, a former Democrat, might join other Democrats to gain political control. Garfield foresaw conflict even before February 1866, when Johnson vetoed a bill to extend the life of the Freedmen's Bureau, charged with aiding the former slaves. By April, Garfield had concluded that Johnson was either "crazy or drunk with opium."[88]

The conflict between the branches of government was the major issue of the 1866 campaign, with Johnson taking to the campaign trail in a Swing Around the Circle and Garfield facing opposition within his party in his home district. With the South still disenfranchised and Northern public opinion behind the Republicans, they gained a two-thirds majority in both houses of Congress. Garfield, having overcome his challengers at his district nominating convention, was easily reelected.[89]

Garfield opposed the initial talk of impeaching Johnson when Congress convened in December 1866,[90] but supported legislation to limit Johnson's powers, such as the Tenure of Office Act, which restricted Johnson in removing presidential appointees. Distracted by committee duties, he rarely spoke about these bills, but was a loyal Republican vote against Johnson. Due to a court case, he was absent on the day in April 1868 when the House impeached Johnson, but soon gave a speech aligning himself with Thaddeus Stevens and others who sought Johnson's removal. When the president was acquitted in trial before the Senate, Garfield was shocked, and blamed the outcome on the trial's presiding officer, Chief Justice Chase, his onetime mentor.[91]

By the time Ulysses S. Grant succeeded Johnson in 1869, Garfield had moved away from the remaining radicals (Stevens, their leader, had died in 1868). He hailed the ratification of the 15th Amendment in 1870 as a triumph, and he favored Georgia's readmission to the Union as a matter of right, not politics. In 1871, Garfield opposed passage of the Ku Klux Klan Act, saying, "I have never been more perplexed by a piece of legislation." He was torn between his indignation at "these terrorists" and his concern for the freedoms endangered by the power the bill gave the president to enforce the act through suspension of habeas corpus.[92]

Tariffs and finance

Throughout his political career, Garfield favored the gold standard and decried attempts to increase the money supply through the issuance of paper money not backed by gold, and later, through the free and unlimited coinage of silver.[93] In 1865, he was placed on the House Ways and Means Committee, a long-awaited opportunity to focus on financial and economic issues. He reprised his opposition to the greenback, saying, "Any party which commits itself to paper money will go down amid the general disaster, covered with the curses of a ruined people."[94] In 1868 Garfield gave a two-hour speech on currency in the House, which was widely applauded as his best oratory to that point; in it he advocated a gradual resumption of specie payments, that is, the government paying out silver and gold, rather than paper money that could not be redeemed.[95]

Tariffs had been raised to high levels during the Civil War. Afterward, Garfield, who made a close study of financial affairs, advocated moving toward free trade, though the standard Republican position was a protective tariff that would allow American industries to grow. This break with his party likely cost him his place on the Ways and Means Committee in 1867, and though Republicans held the majority in the House until 1875, Garfield remained off that committee. Garfield came to chair the powerful House Appropriations Committee, but it was Ways and Means, with its influence over fiscal policy, that he really wanted to lead.[96] Part of the reason he was denied a place on Ways and Means was the opposition of the influential Republican editor Horace Greeley.[97]

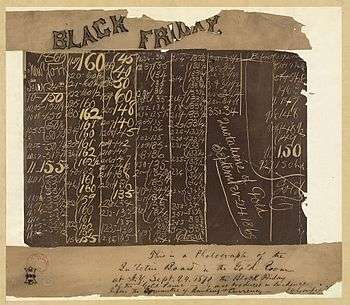

In September 1870, Garfield, then chairman of the House Banking Committee, led an investigation into the Black Friday Gold Panic scandal. The investigation was thorough, but found no indictable offenses. Garfield blamed the easy availability of fiat money greenbacks for financing the speculation that led to the scandal.[98]

Garfield was not at all enthused about President Grant's reelection in 1872—until Greeley, who emerged as the candidate of the Democrats and Liberal Republicans, became the only serious alternative. Garfield said, "I would say Grant was not fit to be nominated and Greeley is not fit to be elected."[99] Both Grant and Garfield were overwhelmingly reelected.[99]

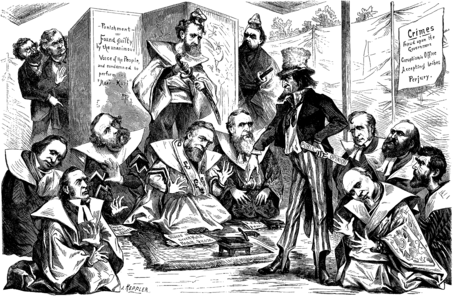

Crédit Mobilier scandal; Salary Grab

The Crédit Mobilier of America scandal involved corruption in the financing of the Union Pacific Railroad, part of the transcontinental railroad that was completed in 1869. Union Pacific officers and directors secretly purchased control of the Crédit Mobilier of America company, then contracted with it to undertake construction of the railroad. The railroad paid the company's grossly inflated invoices with federal funds appropriated to subsidize the project, and the company was allowed to purchase Union Pacific securities at par value, well below the market rate. Crédit Mobilier showed large profits and stock gains, and distributed substantial dividends. The high expenses meant that Congress was called upon to appropriate more funds. One of the railroad officials who controlled Crédit Mobilier was also a congressman, Oakes Ames of Massachusetts. He offered some of his colleagues the opportunity to buy Crédit Mobilier stock at par value, well below what it sold for on the market, and the railroad got its additional appropriations.[100]

The story broke in July 1872, in the middle of the presidential campaign. Among those named were Vice President (and former House Speaker) Schuyler Colfax, Grant's second-term running mate (Massachusetts Senator Henry Wilson), Speaker James G. Blaine of Maine, and Garfield. Greeley had little luck taking advantage of the scandal. When Congress reconvened after the election, Blaine, seeking to clear his name, demanded a House investigation. Evidence before the special committee exonerated Blaine. Garfield had said in September 1872 that Ames had offered him stock but he had repeatedly refused it. Testifying before the committee in January, Ames said that he had offered Garfield ten shares of stock at par value, but that Garfield had never taken them or paid for them, though a year passed, from 1867 to 1868, before Garfield had finally refused. Appearing before the committee on January 14, 1873, Garfield confirmed much of this. Ames testified several weeks later that Garfield agreed to take the stock on credit, and that it was paid for by the company's huge dividends.[101] The two men differed over $300 that Garfield received and later paid back, with Garfield deeming it a loan and Ames a dividend.[102]

Garfield's biographers have been unwilling to exonerate him in Crédit Mobilier. Allan Peskin writes, "Did Garfield lie? Not exactly. Did he tell the truth? Not completely. Was he corrupted? Not really. Even Garfield's enemies never claimed that his involvement ... influenced his behavior."[103] Rutkow writes, "Garfield's real offense was that he knowingly denied to the House investigating committee that he had agreed to accept the stock and that he had also received a dividend of $329."[104] Caldwell suggests that Garfield "told the truth [before the committee]", but "certainly failed to tell the whole truth, clearly evading an answer to certain vital questions and thus giving the impression of worse faults than those of which he was guilty."[105] That Crédit Mobilier was a corrupt organization had been a secret badly kept, even mentioned on the floor of Congress, and editor Sam Bowles wrote at the time that Garfield, in his positions on committees dealing with finance, "had no more right to be ignorant in a matter of such grave importance as this, than the sentinel has to snore on his post."[103]

Another issue that caused Garfield trouble in his 1874 reelection bid was the so-called "Salary Grab" of 1873, which increased the compensation for members of Congress by 50%, retroactive to 1871. Garfield was responsible, as Appropriations Committee chairman, for shepherding the legislative appropriations bill through the House; during the debate in February 1873, Massachusetts Representative Benjamin Butler offered the increase as an amendment, and despite Garfield's opposition, it passed the House and eventually became law. The law was very popular in the House, as almost half the members were lame ducks, but the public was outraged, and many of Garfield's constituents blamed him, though he refused to accept the increase. In a bad year for Republicans, who lost control of the House for the first time since the Civil War, Garfield had his closest congressional election, winning with only 57% of the vote.[lower-alpha 5][107]

Minority leader; Hayes administration

With the Democratic takeover of the House of Representatives in 1875, Garfield lost his chairmanship of the Appropriations Committee. The Democratic leadership in the House appointed Garfield as a Republican member of Ways and Means. With many of his leadership rivals defeated in the 1874 Democratic landslide, and Blaine elected to the Senate, Garfield was seen as the Republican floor leader and the likely Speaker should the party regain control of the chamber.[108]

Garfield thought the land grants given to expanding railroads was an unjust practice. He also opposed some monopolistic practices by corporations, as well as the power sought by workers' unions.[109] Garfield supported the proposed establishment of the United States civil service as a means of ridding officials of the annoyance of aggressive office seekers. He especially wished to eliminate the common practice whereby government workers, in exchange for their positions, were forced to kick back a percentage of their wages as political contributions.[110]

As the 1876 presidential election approached, Garfield was loyal to the candidacy of Senator Blaine, and fought for the former Speaker's nomination at the 1876 Republican National Convention in Cincinnati. When it became clear, after six ballots, that Blaine could not prevail, the convention nominated Ohio Governor Rutherford B. Hayes. Although Garfield had supported Blaine, he had kept good relations with Hayes, and wholeheartedly supported the governor.[111] Garfield had hoped to retire from politics after his term expired to devote himself full-time to the practice of law, but to help his party, he sought re-election, and won it easily that October. Any celebration was short lived, as Garfield's youngest son, Neddie, fell ill with whooping cough shortly after the congressional election, and soon died.[112]

.jpg)

When Hayes appeared to have lost the presidential election the following month to Democrat Samuel Tilden, the Republicans launched efforts to reverse the result in Southern states where they held the governorship: South Carolina, Louisiana, and Florida. If Hayes won all three states, he would take the election by a single electoral vote. Grant asked Garfield to serve as a "neutral observer" in the recount in Louisiana. The observers soon recommended to the state electoral commissions that Hayes be declared the winner—Garfield recommended that the entire vote of West Feliciana Parish, which had given Tilden a sizable majority, be thrown out. The Republican governors of the three states certified that Hayes had won their states, to the outrage of Democrats, who had the state legislatures submit rival returns, and threatened to prevent the counting of the electoral vote—under the Constitution, Congress is the final arbiter of the election. Congress then passed a bill establishing the Electoral Commission, to determine the winner. Although he opposed the Commission, feeling that Congress should count the vote and proclaim Hayes victorious, Garfield was appointed to it over the objections of Democrats that he was too partisan. Hayes emerged the victor by a Commission vote of 8 to 7, with all eight votes being cast by Republican politicians or appointees of that party to the Supreme Court. As part of the deal whereby they recognized Hayes as president, Southern Democrats secured the removal of federal troops from the South, ending Reconstruction.[113]

Although a Senate seat would be disposed of by the Ohio General Assembly after the resignation of John Sherman to become Treasury Secretary, Hayes needed Garfield's expertise to protect him from the agenda of a hostile Congress, and asked him not to seek it. Garfield, as the president's key legislator, gained considerable prestige and respect for his role.[114] When Congress debated what became the Bland–Allison Act, to have the government purchase large quantities of silver and strike it into fully legal tender dollar coins, Garfield fought against this deviation from the gold standard, but it was enacted over Hayes's veto in February 1878.[115]

Garfield during this time purchased the property in Mentor that reporters later dubbed Lawnfield,[116] and from which he would conduct the first successful front porch campaign for the presidency.

U.S. Senate election, 1880

President Hayes suggested that Garfield run for governor in 1879, seeing that as a road that would likely put Garfield in the White House. Garfield preferred to seek election as a U.S. Senator. Rivals were spoken of for the seat, such as Secretary Sherman, but he had presidential ambitions (for which he sought Garfield's support), and other candidates fell by the wayside. Garfield was elected to the Senate by the General Assembly in January 1880, though his term was not scheduled to commence until March 4, 1881.[117] Garfield was never seated in the U.S. Senate.[118]

Legal career and other activities

Garfield was one of three attorneys who argued for the petitioners in the landmark Supreme Court case Ex parte Milligan in 1866. His clients were pro-Confederate northern men who had been found guilty and sentenced to death by a military court for treasonous activities. The case turned on whether the defendants should instead have been tried by a civilian court, and resulted in a ruling that civilians could not be tried before military tribunals while the civil courts were operating. The oral argument was Garfield's first court appearance. Jeremiah Black had taken him in as a junior partner a year before, and assigned the case to him in light of his highly regarded oratory skills. With the result, Garfield instantly achieved a reputation as a preeminent appellate lawyer.[119]

During Grant's first term, discontented with public service, Garfield pursued opportunities in the law, but declined a partnership offer when told his prospective partner was of "intemperate and licentious" reputation.[120] In 1873, after the death of Chase, Garfield appealed to Grant to appoint Justice Noah H. Swayne as Chief Justice. Grant, however, appointed Morrison R. Waite.[121]

In 1876, Garfield displayed his mathematical talent when he developed a trapezoid proof of the Pythagorean theorem. His finding was placed in the New England Journal of Education. Mathematics historian William Dunham wrote that Garfield's trapezoid work was "really a very clever proof."[122]

After his conversion experience in 1850, religious inquiry was a high priority for Garfield. He read widely and moved beyond the narrowness of his early experience as a member of the Disciples of Christ. His new, broader perspective was rooted in his devotion to freedom of inquiry and his study of history. The intensity of Garfield's religious thought was also shaped in part by his experience in combat and his interaction with voters.[123][124]

Presidential election of 1880

Republican nomination

Having just been elected to the Senate with Sherman's support, Garfield entered the 1880 campaign season committed to Sherman as his choice for the Republican presidential nominee.[125] Even before the convention began, however, a few Republicans, including Wharton Barker of Philadelphia, thought Garfield the best choice for the nomination.[125] Garfield denied any interest in the position, but the attention was enough to make Sherman suspicious of his lieutenant's ambitions.[126] Besides Sherman, the early favorites for the nomination were Blaine and former President Grant, but several other candidates attracted delegates as well.[127]

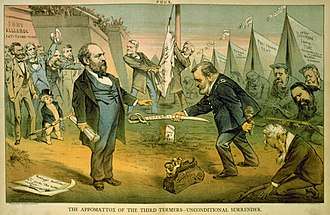

During this period, the Republican Party was split into two factions: The Stalwarts, who supported the existing federal government patronage system; and the Half-Breeds, who supported civil service reform.[128] As the convention began, Senator Roscoe Conkling of New York (the floor leader for the Stalwarts, who supported former President Ulysses S. Grant), proposed that the delegates pledge to support the eventual nominee in the general election.[129] When three West Virginia delegates declined to be so bound, Conkling sought to expel them from the convention. Garfield rose to defend the men, giving a passionate speech in defense of their right to reserve judgment.[129] The crowd turned against Conkling, and he withdrew the motion.[129] The performance delighted Garfield's boosters, who now believed more than ever that he was the only man who could attract a majority of the delegates' votes.[130]

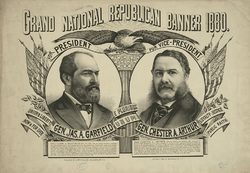

After speeches in favor of the other front-runners, Garfield rose to place Sherman's name in nomination; his nominating speech was well-received, but the delegates mustered little excitement for the idea of Sherman as the next president.[131] The first ballot showed Grant leading with 304 votes and Blaine in second with 284; Sherman's 93 placed him in a distant third. Subsequent ballots quickly demonstrated a deadlock between the Grant and Blaine forces, with neither having the 379 votes needed for nomination.[132] Jeremiah McLain Rusk, a member of the Wisconsin delegation, and Benjamin Harrison, an Indiana delegate, sought to break the deadlock by shifting a few of the anti-Grant votes to a dark horse candidate—Garfield.[133] Garfield gained 50 votes on the 35th ballot, and the stampede began. Garfield protested to the other members of his Ohio delegation that he had not sought the nomination and had never intended to betray Sherman, but they overruled his objections and cast their ballots for him.[134] In the next round of voting, nearly all the Sherman and Blaine delegates shifted their support to Garfield, giving him 399 votes and the Republican nomination. Most of the Grant forces backed the former president to the end, creating a disgruntled Stalwart minority in the party.[135] To obtain that faction's support for the ticket, former New York customs collector Chester A. Arthur, a member of Conkling's political machine, was chosen as the vice presidential nominee.[136]

Campaign against Hancock

Despite including a Stalwart on the ticket, animosity between the Republican factions carried over from the convention, and Garfield traveled to New York to meet with party leaders there.[137] After convincing the Stalwart crowd to put aside their differences and unite for the coming campaign, Garfield returned to Ohio, leaving the active campaigning to others, as was traditional at the time.[138] Meanwhile, the Democrats settled on their nominee, Major General Winfield Scott Hancock of Pennsylvania, a career military officer.[137] Hancock and the Democrats expected to carry the Solid South, while much of the North was considered safe territory for Garfield and the Republicans; most of the campaign would involve a few close states, including New York and Indiana.[139]

Practical differences between the candidates were few, and Republicans began the campaign with the familiar theme of waving the bloody shirt: reminding Northern voters that the Democratic Party was responsible for secession and four years of civil war, and that if Democrats held power they would reverse the gains of that war, dishonor Union veterans, and pay Confederate veterans pensions out of the federal treasury.[140] With fifteen years having passed since the end of the war, and Union generals at the head of both tickets, the bloody shirt was of diminishing value in exciting the voters.[141] With a few months to go before the election, the Republicans switched tactics to emphasize the tariff. Seizing on the Democratic platform's call for a "tariff for revenue only", Republicans told Northern workers that a Hancock presidency would weaken the tariff protection that kept them in good jobs.[142] Hancock made the situation worse when, attempting to strike a moderate stance, he said, "The tariff question is a local question."[141] The ploy proved effective in uniting the North behind Garfield.[143] In the end, fewer than two thousand votes, of the more than 9.2 million popular votes cast, separated the two candidates,[144] but in the Electoral College Garfield had an easy victory over Hancock, 214 to 155.[145]

Presidency, 1881

Cabinet and inauguration

Between his election and his inauguration, Garfield was occupied with assembling a cabinet that would establish peace between Conkling's and Blaine's warring factions. Blaine's delegates had provided much of the support for Garfield's nomination, and the Maine senator received the place of honor: Secretary of State.[146] Blaine was not only the president's closest advisor, he was obsessed with knowing all that took place in the White House, and was even said to have spies posted there in his absence.[147] Garfield nominated William Windom of Minnesota as Secretary of the Treasury, William H. Hunt of Louisiana as Secretary of the Navy, Robert Todd Lincoln as Secretary of War, and Samuel J. Kirkwood of Iowa as Secretary of the Interior. New York was represented by Thomas Lemuel James as Postmaster General. Garfield appointed Pennsylvania's Wayne MacVeagh, an adversary of Blaine's, as Attorney General.[148] Blaine tried to sabotage the appointment by convincing Garfield to name an opponent of MacVeagh, William E. Chandler, as Solicitor General under MacVeagh. Only Chandler's rejection by the Senate forestalled MacVeagh's resignation over the matter.[149]

Distracted by cabinet maneuvering, Garfield's inaugural address was not up to his typical oratorical standards.[150] In one high point, Garfield emphasized the civil rights of African-Americans, saying "Freedom can never yield its fullness of blessings so long as the law or its administration places the smallest obstacle in the pathway of any virtuous citizen."[151] After discussing the gold standard, the need for education, and an unexpected denunciation of Mormon polygamy, the speech ended. The crowd applauded, but the speech, according to Peskin, "however sincerely intended, betrayed its hasty composition by the flatness of its tone and the conventionality of its subject matter."[152]

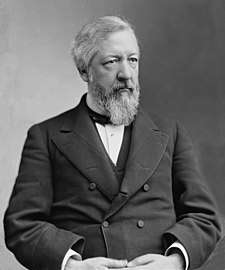

Garfield's appointment of James infuriated Conkling, a factional opponent of the Postmaster General, who demanded a compensatory appointment for his faction, such as the position of Secretary of the Treasury. The resulting squabble occupied much of Garfield's brief presidency. The feud with Conkling reached a climax when the president, at Blaine's instigation, nominated Conkling's enemy, Judge William H. Robertson, to be Collector of the Port of New York. This was one of the prize patronage positions below cabinet level, and was then held by Edwin A. Merritt. Conkling raised the time-honored principle of senatorial courtesy in an attempt to defeat the nomination, to no avail. Garfield, who believed the practice was corrupt, would not back down and threatened to withdraw all nominations unless Robertson was confirmed, intending to "settle the question whether the president is registering clerk of the Senate or the Executive of the United States."[153] Ultimately, Conkling and his New York colleague, Senator Thomas C. Platt, resigned their Senate seats to seek vindication, but found only further humiliation when the New York legislature elected others in their places. Robertson was confirmed as Collector and Garfield's victory was clear. To Blaine's chagrin, the victorious Garfield returned to his goal of balancing the interests of party factions, and nominated a number of Conkling's Stalwart friends to offices.[154]

Supreme Court nomination

In 1880, President Hayes had nominated Stanley Matthews to the Supreme Court of the United States. The U.S. Senate declined to act on the Matthews nomination. In March 1881, Garfield re-nominated Matthews to the Supreme Court.[155] The Senate confirmed Matthews to the high Court by a vote of 24-23.[156] According to The New York Times, "opposition to Matthews's Supreme Court appointment ...stemmed from his prosecution in 1859 of a newspaper editor who had assisted two runaway slaves." Because Matthews was "a professed abolitionist at the time, the case was later framed as political expediency triumphing over moral principle."[155] Matthews served on the Court until his death in 1889.[155]

Reforms

Grant and Hayes had both advocated civil service reform, and by 1881, civil service reform associations had organized with renewed energy across the nation. Garfield sympathized with them, believing that the spoils system damaged the presidency and distracted from more important concerns.[157] Some reformers were disappointed that Garfield had advocated limited tenure only to minor office seekers and had given appointments to his old friends, but many remained loyal and supported Garfield.[157]

Corruption in the post office also cried out for reform. In April 1880, there had been a congressional investigation into corruption in the Post Office Department, in which profiteering rings allegedly stole millions of dollars, securing bogus mail contracts on star routes.[158] After obtaining contracts with the lowest bid, costs to run the mail routes would be escalated and profits would be divided among ring members. That year, Hayes stopped the implementation of any new star route contracts. Shortly after taking office, Garfield received information from Attorney General MacVeagh and Postmaster General James of postal corruption by an alleged star route ringleader, Second Assistant Postmaster General Thomas J. Brady.[159] Garfield demanded Brady's resignation and ordered prosecutions that would end in trials for conspiracy. When told that his party, including his own campaign manager, Stephen W. Dorsey, was involved, Garfield directed MacVeagh and James to root out the corruption in the Post Office Department "to the bone", regardless of where it might lead.[158] Brady resigned and was eventually indicted for conspiracy. After two "star route" ring trials in 1882 and 1883, the jury found Brady not guilty.[160]

Civil rights and education

Garfield believed that the key to improving the state of African American civil rights would be found in education aided by the federal government.[161] During Reconstruction, freedmen had gained citizenship and suffrage that enabled them to participate in government, but Garfield believed their rights were being eroded by Southern white resistance and illiteracy, and was concerned that blacks would become America's permanent "peasantry."[162] He answered by proposing a "universal" education system funded by the federal government. Congress and the northern white public, however, had lost interest in African-American rights, and federal funding for universal education did not find support in Congress during Garfield's term.[162] Garfield also worked to appoint several African Americans to prominent positions: Frederick Douglass, recorder of deeds in Washington; Robert Elliot, special agent to the Treasury; John M. Langston, Haitian minister; and Blanche K. Bruce, register to the Treasury. Garfield believed that Southern support for the Republican party could be gained by "commercial and industrial" interests rather than race issues and began to reverse Hayes's policy of conciliating Southern Democrats.[163] He appointed William H. Hunt, a carpetbagger Republican from Louisiana, as Secretary of the Navy.[163] To break the hold of the resurgent Democratic Party in the Solid South, Garfield took patronage advice from Virginia Senator William Mahone of the biracial independent Readjuster Party, hoping to add the independents' strength to the Republicans' there.[164]

Foreign policy and naval reform

Entering the presidency, Garfield had little foreign policy experience, so he leaned heavily on Blaine. Blaine, a former protectionist, now agreed with Garfield on the need to promote freer trade, especially within the Western Hemisphere.[165] Their reasons were twofold: firstly, Garfield and Blaine believed that increasing trade with Latin America would be the best way to keep Great Britain from dominating the region.[165] Secondly, by encouraging exports, they believed they could increase American prosperity.[165] Garfield authorized Blaine to call for a Pan-American conference in 1882 to mediate disputes among the Latin American nations and to serve as a forum for talks on increasing trade.[166] At the same time, they hoped to negotiate a peace in the War of the Pacific then being fought by Bolivia, Chile, and Peru.[166] Blaine favored a resolution that would not result in Peru yielding any territory, but Chile, which by 1881 had occupied the Peruvian capital, Lima, rejected any settlement that restored the previous status quo.[167] Garfield sought to expand American influence in other areas, calling for renegotiation of the Clayton-Bulwer Treaty to allow the United States to construct a canal through Panama without British involvement, as well as attempting to reduce British influence in the strategically located Kingdom of Hawaii.[168] Garfield's and Blaine's plans for the United States' involvement in the world stretched even beyond the Western Hemisphere, as he sought commercial treaties with Korea and Madagascar.[169] Garfield also considered enhancing the United States' military strength abroad, asking Navy Secretary Hunt to investigate the condition of the navy with an eye toward expansion and modernization.[170] In the end, these ambitious plans came to nothing after Garfield was assassinated. Nine countries had accepted invitations to the Pan-American conference, but the invitations were withdrawn in April 1882 after Blaine resigned from the cabinet and Arthur, Garfield's successor, cancelled the conference.[171][lower-alpha 6] Naval reform continued under Arthur, if on a more modest scale than Garfield and Hunt had envisioned, ultimately ending in the construction of the Squadron of Evolution.[172]

Administration and cabinet

| The Garfield Cabinet | ||

|---|---|---|

| Office | Name | Term |

| President | James A. Garfield | 1881 |

| Vice President | Chester A. Arthur | 1881 |

| Secretary of State | James G. Blaine | 1881 |

| Secretary of the Treasury | William Windom | 1881 |

| Secretary of War | Robert Todd Lincoln | 1881 |

| Attorney General | Wayne MacVeagh | 1881 |

| Postmaster General | Thomas Lemuel James | 1881 |

| Secretary of the Navy | William H. Hunt | 1881 |

| Secretary of the Interior | Samuel J. Kirkwood | 1881 |

Assassination

Guiteau and shooting

Garfield was shot by Charles J. Guiteau, a disgruntled office seeker, at the Baltimore and Potomac Railroad Station in Washington, D.C. on July 2, 1881. After eleven weeks of intensive care Garfield died in Elberon, New Jersey, the second of four presidents to be assassinated, following Abraham Lincoln.

Guiteau had followed various professions in his life, but in 1880 had determined to gain federal office by supporting what he expected would be the winning Republican ticket.[173] He composed a speech, "Garfield vs. Hancock", and got it printed by the Republican National Committee. One means of persuading the voters in that era was through orators expounding on the candidate's merits, but with the Republicans seeking more famous men, Guiteau received few opportunities to speak.[174] On one occasion, according to Kenneth D. Ackerman in his book about Garfield's candidacy and assassination, Guiteau was unable to finish his speech due to nerves. Guiteau, who considered himself a Stalwart, deemed his contribution to Garfield's victory sufficient to justify the position of consul in Paris, despite the fact that he spoke no French, nor any foreign language.[175] Guiteau has since been described by one medical expert as possibly being a narcissistic schizophrenic;[176] neuroscientist Kent Kiehl assessed him as being a clinical psychopath.[177]

One of President Garfield's more wearying duties was seeing office seekers, and he saw Guiteau at least once. White House officials suggested to Guiteau that he approach Blaine, as the consulship was within the Department of State.[178] Blaine also saw the public regularly, and Guiteau became a regular at these sessions. Blaine, who had no intention of giving Guiteau a position he was unqualified for and had not earned, simply stated that the deadlock in the Senate over Robertson's nomination made it impossible to consider the Paris consulship, which required Senate confirmation.[179] Once the New York senators had resigned, and Robertson had been confirmed as Collector, Guiteau pressed his claim, and Blaine told him he would not receive the position.[180]

Guiteau came to believe he had lost the position because he was a Stalwart. The office-seeker decided that the only way to end the internecine warfare in the Republican Party was for Garfield to die—though he had nothing personal against the president. Arthur's succession would restore peace, he felt, and lead to rewards for fellow Stalwarts, including Guiteau.[181]

The assassination of Abraham Lincoln was deemed a fluke due to the Civil War, and Garfield, like most people, saw no reason why the president should be guarded; Garfield's movements and plans were often printed in the newspapers. Guiteau knew the president would leave Washington for a cooler climate on July 2, and made plans to kill him before then. He purchased a gun he thought would look good in a museum, and followed Garfield several times, but each time his plans were frustrated, or he lost his nerve.[182] His opportunities dwindled to one—Garfield's departure by train for New Jersey on the morning of July 2, 1881.[183]

Guiteau concealed himself by the ladies' waiting room at the Sixth Street Station of the Baltimore and Potomac Railroad, from where Garfield was scheduled to depart. Most of Garfield's cabinet planned to accompany him at least part of the way. Blaine, who was to remain in Washington, came to the station to see him off. The two men were deep in conversation and did not notice Guiteau before he took out his revolver and shot Garfield twice, once in the back and once in the arm. The time was 9:30 a.m. The assassin attempted to leave the station, but was quickly captured.[184] As Blaine recognized him and Guiteau made no secret of why he had shot Garfield, the assassin's motivation to benefit the Stalwarts reached many with the early news of the shooting, causing rage against that faction.[185]

Treatment and death

Garfield was struck by two shots; one glanced off his arm while the other pierced his back, shattering a rib and embedding itself in his abdomen. "My God, what is this?" he exclaimed.[186] Guiteau, as he was led away, stated, "I did it. I will go to jail for it. I am a Stalwart and Arthur will be President."[lower-alpha 7][187]

Among those at the station was Robert Todd Lincoln, who was deeply upset, thinking back to when his father Abraham Lincoln was assassinated 16 years earlier. Garfield was taken on a mattress upstairs to a private office, where several doctors examined him, probing the wound with unwashed fingers. At his request, Garfield was taken back to the White House, and his wife, then in New Jersey, was sent for.[188] Blaine sent word to Vice President Arthur in New York City, who received threats against his life because of his animosity toward Garfield and Guiteau's statements.[189]

Although Joseph Lister's pioneering work in antisepsis was known to American doctors, with Lister himself having visited America in 1876, few of them had confidence in it, and none of his advocates were among Garfield's treating physicians.[190] The physician who took charge at the depot and then at the White House was Doctor Willard Bliss.[lower-alpha 8] A noted physician and surgeon, Bliss was an old friend of Garfield, and about a dozen doctors, led by Bliss, were soon probing the wound with unsterilized fingers and instruments. Garfield was given morphine for the pain, and asked Bliss to frankly tell him his chances, which Bliss put at one in a hundred. "Well, Doctor, we'll take that chance."[191]

Over the next few days, Garfield made some improvement, as the nation viewed the news from the capital and prayed. Although he never stood again, he was able to sit up and write several times, and his recovery was viewed so positively that a steamer was fitted out as a seagoing hospital to aid with his convalescence. He was nourished on oatmeal porridge (which he detested) and milk from a cow on the White House lawn. When told that Indian chief Sitting Bull, a prisoner of the army, was starving, Garfield said, "Let him starve," then, "Oh, no, send him my oatmeal."[192] X-radiation (or X-ray) usage, which likely would have helped the president's physicians determine exactly where the bullet was lodged in his body, would not be invented for another fourteen years. Alexander Graham Bell tried to locate the bullet with a primitive metal detector. He was not successful, although the invention had been effective when tested on others. The problem was that Bliss limited the extent of its use on Garfield, taking control of the experiment and ensuring that he remained in charge. Because Bliss thought that the bullet rested in someplace that it did not, the detector was unable to locate it. Shortly after the first attempt, Bell returned for another test after enhancing the abilities of his invention. The test resulted in a noise around the area that Bliss believed to be where the bullet was lodged, despite the sound being different from what Bell heard in his previous tests. Bliss took this as confirmation that the bullet was where he declared it to be. Bliss wrote in a bulletin that the test was a success, and that it was "now unanimously agreed that the location of the ball has been ascertained with reasonable certainty, and that it lies, as heretofore stated, in the front wall of the abdomen, immediately over the groin, about five inches below and to the right of the navel." [193]

One means of keeping the president comfortable in Washington's summer heat was one of the first successful air conditioning units: air that was propelled by fans over ice and then dried had reduced the temperature in the sickroom by 20 degrees Fahrenheit (11 degrees Celsius).[192] Engineers from the navy, along with some scientists, worked together to develop this version of air conditioning in an attempt to help the president recover. There were some issues, such as it made excessive noise and immensely increased the humidity in Garfield's room, but the engineers worked hard to find solutions for these problems in their efforts to ease Garfield's suffering.[194]

Beginning on July 23, Garfield took a turn for the worse. His temperature increased to 104 °F (40 °C); doctors, concerned by an abscess that had developed by the wound, operated and inserted a drainage tube. This initially seemed to help, and Garfield, in his bed, was able to hold a brief cabinet meeting on July 29, though members were under orders from Bliss to discuss nothing that might excite Garfield.[195] Doctors probed the abscess, which went into Garfield's body, hoping to find the bullet; they most likely only made the infections worse. Garfield performed only one state act in August, signing an extradition paper. By the end of the month, the president was much more feeble than he had been, and his weight had decreased from 210 pounds (95 kg)[196] to 130 pounds (59 kg).[197]

Garfield had long been anxious to escape hot, unhealthy Washington, and in early September the doctors agreed to move him to Elberon, part of Long Branch, New Jersey, where his wife had recovered earlier in the summer. He left the White House for the last time on September 5, traveling in a specially cushioned railway car; a spur line to the Francklyn Cottage, a seaside mansion given over to his use, was built in a night by volunteers. There, Garfield could see the ocean as officials and reporters maintained what became (after an initial rally) a death watch. Garfield's personal secretary, Joe Stanley Brown, wrote 40 years later, "to this day I cannot hear the sound of the low slow roll of the Atlantic on the shore, the sound which filled my ears as I walked from my cottage to his bedside, without recalling again that ghastly tragedy."[198]

On September 18, Garfield asked Colonel A.F. Rockwell, a friend, if he would have a place in history. Rockwell assured him he would, and told Garfield he had much work still before him. But his response was, "No, my work is done."[199] The following day, Garfield, by then also suffering from pneumonia and heart pains, marveled that he could not pick up a glass despite feeling well, and went to sleep without discomfort. He awoke that evening around 10:15 p.m. complaining of great pain in his chest to his chief of staff and friend General David Swaim, who was watching him, as he placed his hand on his breast over his heart.[200] The president then requested a drink of water from Swaim. After finishing his glass, Garfield said, "Oh Swaim, this terrible pain – press your hand on it." As Swaim obligingly put his hand on Garfield's chest, Garfield's hands went up reflexively. Clutching his heart, he exclaimed, "Oh, Swaim, can't you stop this? Oh, oh, Swaim!"[201] Swaim ordered another attendant to send for Bliss, who found Garfield unconscious. Despite efforts to revive him, Garfield never awoke, and he died at 10:30 p.m., aged 49.[202] Learning from a reporter of Garfield's death, Chester A. Arthur took the presidential oath of office administered by New York Supreme Court Justice John R. Brady.[203]

According to some historians and medical experts, Garfield might have survived his wounds had the doctors attending him had at their disposal today's medical research, knowledge, techniques, and equipment.[204][205][206] Standard medical practice at the time dictated that priority be given to locating the path of the bullet. Several of his doctors inserted their unsterilized fingers into the wound to probe for the bullet, a common practice in the 1880s.[204] Historians agree that massive infection was a significant factor in Garfield's demise.[204] Biographer Peskin stated that medical malpractice did not contribute to Garfield's death; the inevitable infection and blood poisoning that would ensue from a deep bullet wound resulted in damage to multiple organs and spinal bone fragmentation.[207] Rutkow, a professor of surgery at the University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey, has argued that starvation also played a role. Rutkow suggests that "Garfield had such a nonlethal wound. In today's world, he would have gone home in a matter of two or three days."[204] The conventional narrative regarding Garfield's post-shooting medical condition was challenged by Theodore Pappas and Shahrzad Joharifard in a 2013 article in the The American Journal of Surgery. They argued that Garfield died from a late rupture of a splenic artery pseudoaneurysm (that initially developed shortly after the shooting, thus preventing Garfield from bleeding to death immediately after he was shot but instead allowing him to live for an additional 80 days). They also argued that the symptoms that Garfield suffered in the last couple of months of his life were actually caused by acute cholecystitis. Based on Garfield's autopsy report, the authors speculate this condition developed as a result of his doctors accidentally puncturing his bladder in July 1881, three or four weeks after he was shot. Pappas and Joharifard say this caused the decline in Garfield's condition that was visible starting from July 23, 1881.[208]

Guiteau was indicted on October 14, 1881, for the murder of the president. Guiteau declared that he was not responsible for the death of Garfield. He admitted to the shooting but not the killing. In his defense, Guiteau wrote: "General Garfield died from malpractice. According to his own physicians, he was not fatally shot. The doctors who mistreated him ought to bear the odium of his death, and not his assailant. They ought to be indicted for murdering James A. Garfield, and not me."[209] In a chaotic trial in which Guiteau often interrupted and argued, and in which his counsel used the insanity defense, the jury found him guilty on January 5, 1882, and he was sentenced to death by hanging. Guiteau might have had neurosyphilis, a disease that causes physiological mental impairment.[210] He was executed on June 30, 1882.[211]

Funeral, memorials and commemorations

Garfield's funeral train left Long Branch on the same special track that had brought him there, traveling over tracks blanketed with flowers and past houses adorned with flags. His body was transported to the Capitol and then continued on to Cleveland for burial.[212] More than 70,000 citizens, some waiting over three hours, passed by Garfield's coffin as his body lay in state at the United States Capitol rotunda; later, on September 25, 1881, in Cleveland, more than 150,000—a number equal to the entire population of that city—likewise paid their respects.[212] His body was temporarily interred in a vault in Cleveland's Lake View Cemetery until his permanent memorial was built.[212]

.jpeg)

Memorials to Garfield were erected across the country. On April 10, 1882, seven months after Garfield's death, the U.S. Post Office Department issued a postage stamp in his honor.[213] In 1884, sculptor Frank Happersberger completed a monument on the grounds of the San Francisco Conservatory of Flowers.[214] In 1887, the James A. Garfield Monument was dedicated in Washington.[215] Another monument, in Philadelphia's Fairmount Park, was erected in 1896.[216] In Victoria, Australia, Cannibal Creek was renamed Garfield in his honor.[217]

On May 19, 1890, Garfield's body was permanently interred, with great solemnity and fanfare, in a mausoleum in Lake View Cemetery in Cleveland. Attending the dedication ceremonies were former President Hayes, President Benjamin Harrison, and future president William McKinley.[218] Garfield's Treasury Secretary, William Windom, also attended.[218] Harrison said that Garfield was always a "student and instructor" and that his life works and death would "continue to be instructive and inspiring incidents in American history".[219] Three panels on the monument display Garfield as a teacher, Union major general, and orator; another shows him taking the presidential oath, and a fifth shows his body lying in state at the Capitol rotunda in Washington, D.C.[220]

Garfield's murder by a deranged office-seeker awakened public awareness of the need for civil service reform legislation. Senator George H. Pendleton, a Democrat from Ohio, launched a reform effort that resulted in the Pendleton Act in January 1883.[221] This act reversed the "spoils system" where office seekers paid up or gave political service to obtain or keep federally appointed positions.[221] Under the act, appointments were awarded on merit and competitive examination.[222] To ensure that the reform was implemented, Congress and Arthur established and funded the Civil Service Commission. The Pendleton Act, however, covered only 10% of federal government workers.[222] For Arthur, previously known for having been a "veteran spoilsman", civil service reform became his most noteworthy achievement.[223]

A marble statue of Garfield by Charles Niehaus was added to the National Statuary Hall Collection in the Capitol in Washington D.C., a gift from the State of Ohio in 1886.[224]

On March 2, 2019, the National Park Service erected exhibit panels in Washington to mark the site of the assassination.[225]

Garfield's casket lying in state at the Capitol Rotunda

Garfield's casket lying in state at the Capitol Rotunda Garfield Memorial at Lake View Cemetery in Cleveland, Ohio

Garfield Memorial at Lake View Cemetery in Cleveland, Ohio

First Garfield postage stamp, 1882

First Garfield postage stamp, 1882

Legacy and historical view

For a few years after his assassination, Garfield's life story was seen as an exemplar of the American success story—that even the poorest boy might someday become President of the United States. Peskin noted that, "In mourning Garfield, Americans were not only honoring a president; they were paying tribute to a man whose life story embodied their own most cherished aspirations."[226] As the rivalry between Stalwarts and Half-Breeds faded from the scene in the late 1880s and after, so too did memories of Garfield. In the 1890s, Americans became disillusioned with politicians, and looked elsewhere for inspiration, focusing on industrialists, labor leaders, scientists, and others as their heroes. Increasingly, Garfield's short time as president was forgotten.[227]

The 20th century saw no revival for Garfield. Thomas Wolfe deemed the presidents of the Gilded Age, including Garfield, "lost Americans" whose "gravely vacant and bewhiskered faces mixed, melted, swam together".[228] The politicians of the Gilded Age faded from the public eye, their luster eclipsed by those who had influenced America outside of political office during that time: the robber barons, the inventors, those who had sought social reform, and others who had lived as America rapidly changed. Current events and more recent figures occupied America's attention: according to Ackerman, "the busy Twentieth Century has made Garfield's era seem remote and irrelevant, its leaders ridiculed for their very obscurity".[228]

Garfield's biographers, and those who have studied his presidency, tend to think well of him, and that his presidency saw a promising start before its untimely end. Historian Justus D. Doenecke, while deeming Garfield a bit of an enigma, chronicles his achievements: "by winning a victory over the Stalwarts, he enhanced both the power and prestige of his office. As a man, he was intelligent, sensitive, and alert, and his knowledge of how government worked was unmatched."[229] Yet Doenecke criticizes Garfield's dismissal of Merritt in Robertson's favor, and wonders if the president was truly in command of the situation even after the latter's confirmation.[230] According to Caldwell, writing in 1931, "If Garfield lives in history, it will be partly on account of the charm of his personality—but also because in life and in death, he struck the first shrewd blows against a dangerous system of boss rule which seemed for a time about to engulf the politics of the nation. Perhaps if he had lived he could have done no more."[231] Rutkow writes, "James Abram Garfield's presidency is reduced to a tantalizing 'what if.'"[227]

Peskin believes Garfield deserves more credit for his political career than he has received:

True, his accomplishments were neither bold nor heroic, but his was not an age that called for heroism. His stormy presidency was brief, and in some respects, unfortunate, but he did leave the office stronger than he found it. As a public man he had a hand in almost every issue of national importance for almost two decades, while as a party leader he, along with Blaine, forged the Republican Party into the instrument that would lead the United States into the twentieth century.[232]

See also

- List of Presidents of the United States

Notes

- Church of Christ, Christian Church, and Disciples of Christ were names that were used interchangeably amongst members of a unified movement until the turn of the 20th century when they separated.[17]

- Biographer Allan Peskin speculated this may have been infectious hepatitis.[49]

- Until the ratification of the Twentieth Amendment in 1933, Congress convened annually in December.

- In a July 1865 letter to Governor Jacob Dolson Cox, Garfield wrote that he felt "a strong sense of repugnance when I think of the negro being made our political equal and I would be glad if they could be colonized, sent to heaven, or got rid of in any decent way ... but colonization has proved a hopeless failure everywhere."[87]

- Garfield typically won two or three times his Democratic opponents' votes.[106]

- In October 1883, the War of the Pacific was settled without American involvement, with the Treaty of Ancón.

- The words vary in some sources

- "Doctor" was his given name.

References

- "The election of President James Garfield of Ohio". United States House of Representatives. Retrieved June 23, 2015.

- Peskin 1978, pp. 4–6.

- Peskin 1978, pp. 6–7.

- Peskin 1978, pp. 8–10.

- Rutkow 2006, p. 4.

- Peskin 1978, pp. 10–11.

- Brown 1881, p. 23.

- Brown 1881, pp. 30–33.

- Rutkow 2006, p. 10.

- Peskin 1978, pp. 14–17.

- Peskin 1978, p. 13.

- Rutkow 2006, p. 6.

- Brown 1881, pp. 71–73.

- Brown 1881, pp. 47–49.

- Peskin 1978, p. 16.

- Peskin 1978, p. 17.

- McAlister & Tucker 1975, p. 252.

- Peskin 1978, p. 21.

- Peskin 1978, pp. 27–28.

- Peskin 1978, pp. 22–23.

- Peskin 1978, p. 29.

- Brown 1881, p. 56; Peskin 1978, p. 30.

- Peskin 1978, p. 34.

- Rutkow 2006, p. 8.

- "Phi Beta Kappa Presidents". PBK. Retrieved April 3, 2020.

- Rutkow 2006, p. 11.

- Rutkow 2006, p. 44.