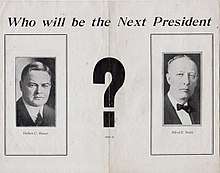

Al Smith 1928 presidential campaign

Al Smith, Governor of New York, was a candidate for President of the United States in the 1928 election. His run was notable in that he was the first Catholic nominee of a major party, he opposed Prohibition, and he enjoyed broad appeal among women, who had won the right of suffrage in 1920.

| Al Smith 1928 presidential campaign | |

|---|---|

| |

| Campaign | U.S. presidential election, 1928 |

| Candidate |

|

| Affiliation | Democratic Party |

| Status | Lost election: November 6, 1928 |

| Headquarters | Albany, New York[1] |

| Key people | Joseph M. Proskauer (campaign manager)[1] Robert Moses[1] Belle Moskowitz[1] Franklin D. Roosevelt[1] |

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

Governor of New York

Member of the

|

||

Background

Al Smith was the governor of New York from 1919 to 1920 and 1923 to 1928. His running mate, Joseph Taylor Robinson, was a senator from Arkansas and future Senate Majority Leader.

After failing to secure the nomination at the 1924 Democratic National Convention, which featured a 103-ballot deadlock between Smith and William McAdoo, Smith ran again for the presidency in 1928.

Primary campaign

Soon after the 1924 election, Smith's supporters began laying the groundwork for a 1928 effort.[2] Smith enjoyed continued popularity in the North.[2]

Anti-Catholicism and anti-Tammany sentiments were a major obstacle to Smith's nomination. Smith's opposition distributed booklets which capitalized on these topics.[2] Franklin Delano Roosevelt, a Protestant, proved to be a significant advocate for Smith, capable of transcending the issue of religion.[2]

Also active within Smith's campaign was Charles Poletti.[2]

Smith's candidacy faced the obstacle of opposition from the forces of the Ku Klux Klan. In August 1925, a march was held in Washington, D.C., where thousands of hooded klansmen aimed to display both their power and their opposition to new forces in the Democratic Party. In an implied reference to Smith, imperial wizard Hiram Wesley Evans declared that the Klan was opposed to the granting of "political power to any Roman Catholic".[2]

Roosevelt was informed by a top-ranking Democrat from Utah that its states delegates would be available to Smith, if he ran. The same individual also expressed certainty that Smith would carry the state during the general election if nominated.[2]

Some of Smith's supporters within the Tammany Hall organization wanted to confront critics of Smith in regions of the country more hostile to Smith's candidacy and advocated for the development a national organization based upon the Tammany model.[2] However, in late 1926, Roosevelt wrote Smith a letter which strongly warned against this move, believing that it would give opposition greater cause to organize against Smith.[2] In this letter, Roosevelt wrote,

I know perfectly well that you, as you read this letter, say to yourself quite honestly that you are not a candidate for 1927 and you can't be bothered with trying to control your fool friends ... Nevertheless, you will be a candidate in 1928 whether you like it or not and I want to see you as strong a candidate as it is honestly possible to make you when the convention meets.[2]

By 1928 Smith had become regarded as an immensely formidable candidate for the nomination.[2] Many potential credible opponents, such as McAdoo, decided not to run against Smith, believing that Smith's prospects of securing the nomination made challenging him a fool's errand.[2] As a consequence, Smith was able to secure status as the party's presumptive nominee heading into the convention.[3]

At the convention anti-Smith forces made a last-ditch attempt to deny him the nomination by trying to promote the pro-prohibition Catholic [4] Thomas J. Walsh as a possible candidate in an effort to siphon off Smith delegates that were wary of his anti-prohibition position. This effort failed and Smith handily managed to win the nomination.[5]

Roosevelt served as Smith's floor manager and delivered his nominating speech, which received tremendous applause. Some even suggested that Roosevelt might make a better presidential candidate, being a Protestant and a bearer of the Roosevelt name (Theodore Roosevelt was immensely popular).

Former Boston mayor Andrew James Peters delivered a seconding speech for Smith.[2]

In contrast to the long convention held four years prior, the 1928 convention lasted only three days.[6]

The convention was broadcast via radio, allowing Smith to follow it from Albany.[2]

At the convention, the party leadership selected Joseph Taylor Robinson as their favored vice-presidential nominee, as he balanced-out the ticket. Robinson won the vice-presidential nomination, thus becoming Smith's running mate.[7][8]

General election campaign

Reporter Frederick William Wile made the oft-repeated observation that Smith was defeated by "the three P's: Prohibition, Prejudice and Prosperity".[9] The Republican Party was still benefiting from an economic boom, as well as a failure to reapportion Congress and the electoral college following the 1920 census, which had registered a 15 percent increase in the urban population. Smith's economic conservatism and anti-prohibition stance likely contributed to his inability to coalesce support amongst rural progressives.[10] Smith's opponent, Republican nominee Herbert Hoover, was vastly popular. Additionally, Hoover was running on the record of an immensely popular incumbent Republican president, Calvin Coolidge.[3] Hoover benefited incredibly from the perception of Republican-led economic prosperity, which, less than a year later, would be proven to have been an illusion.[2]

Anti-Catholic prejudice

Historians agree that prosperity, along with widespread anti-Catholic sentiment against Smith, made Hoover's election inevitable.[11] He defeated Smith by a landslide in the 1928 election, carrying five southern states in crossover voting by conservative white Democrats (since disenfranchisement of blacks in the South at the turn of the century, whites dominated voting.) Many Democratic leaders had hoped that nominating the Irish Catholic Smith might help the party to restore its coalition of ethnic support which had eroded by the Wilson presidency, and had continued to erode during the 1920 and 1924 elections. In the latter election, Catholic Robert M. La Follette Sr. fielded a strong third-party campaign).[10]

The Ku Klux Klan held cross burnings across the country in protest to his nomination and people feared that a Catholic [12] would be more loyal to the Pope than to the American people.[1][3][5]

Smith failed to come across a successful strategy to combat arguments that targeted his faith.[3] Some accusations, such as one that Smith would quite literally hand-over the White House to the Pope, were so ludicrous that it would be fruitless for Smith to even begin trying to address them.[3]

The issue of religious prejudice was compounded by the fact that many voters also distrusted people from large cities. Thus, many were particularly uncomfortable voting for Smith, who hailed from New York City, the largest of American cities.[3]

New York State

Smith was counting on a win in his home state of New York,[1] which had the most electoral votes of any state.[13]

Under New York election laws, no individual could be on the ballot for both President and Governor in the same election cycle, so Smith did not run for reelection as Governor of New York. Smith convinced Franklin Roosevelt to run for governor in his place.[1]

Roosevelt had initially been reluctant to run for governor in 1928. Since at least the early 1920s, Roosevelt had planned to seek the governorship, viewing it as a stepping-stone to the Presidency.[1][14] However, Roosevelt's plans had long included a gubernatorial campaign in 1932 and a presidential candidacy in 1936. Roosevelt and his close adviser Louis M. Howe were both convinced that this timeline was still wise. They believed this due to their anticipation that 1928 was going to be a poor year for Democrats, due to a prosperous economy under an incumbent Republican White House.[1][14]

Smith was still confident that Roosevelt was the only individual capable of defeating Albert Ottinger, the particularly appealing Republican Party nominee for Governor. Smith estimated that Roosevelt would be capable of drawing 200,000 more votes than any other prospective Democrat. Smith also thought that Roosevelt running for governor would boost voter turnout among Protestant Democrats in Upstate New York, without which Smith might lose his home state (and its crucial 45 electoral votes).[1]

In September, Smith formally approached Roosevelt about running for governor. However, he failed to convince Roosevelt to commit to running.[1] Still unwilling to run, Roosevelt attempted to place himself out-of-reach from state leaders seeking to convince him otherwise. As the New York Democratic Party was preparing to convene in Rochester, Roosevelt vacationed in Warm Springs. However, on the eve of the convention, Smith reached Roosevelt by telephone and persuaded him to accept the nomination.[1][2] Jimmy Walker, then a friend to Roosevelt, placed his name into nomination at the convention.[2]

Smith's political operative Robert Moses, who secretly had hoped for Smith to offer him the nomination, was very critical of Smith's choice of Roosevelt.[1][15]

Roosevelt had come to Smith's defense near the close of the election. However, Smith ultimately lost New York by several hundred thousand votes.[1][2]

Outcome

Smith was an articulate proponent of good government and efficiency, as was Hoover. Smith swept the entire Catholic vote, which had been split in 1920 and 1924 between the parties, and attracted millions of Catholics, generally ethnic whites, to the polls for the first time and especially women, who were first allowed to vote in 1920.

Smith lost important Democratic constituencies in the rural North and in southern cities and suburbs. He, however, succeeded in the Deep South in part because of the appeal of his running mate, Senator Joseph Robinson from Arkansas, but he lost five southern states to Hoover. Smith carried the ten most populous cities in the United States, an indication of the rising power of the urban areas and their new demographics.

In addition to the issues noted above, Smith was not a very good campaigner. His campaign theme song, "The Sidewalks of New York", had little appeal for rural folks, and they found his 'city' accent, when heard on the "radio," seemed slightly foreign. Smith narrowly lost New York, whose electors were biased to rural upstate and largely Protestant precincts. While the future Democratic presidential candidate Franklin D. Roosevelt managed to win the New York gubernatorial election, Smith nevertheless lost his home state and the presidential election to the Republican candidate Hoover and he became the first Democratic candidate since Reconstruction to lose more than one southern state.[16]

Legacy

Smith ran again, unsuccessfully, for the Democratic nomination in 1932.

In 1928 James A. Farley left Smith's camp to run Franklin D. Roosevelt's successful campaign for Governor, and later Roosevelt's successful campaigns for the Presidency in 1932 where he defeated Al Smith and 1936. However, despite the anti-Catholic prejudice every presidential candidate since 1960 has honored Smith by going to the Alfred E. Smith Memorial Foundation Dinner and in 1960 John F. Kennedy the only Catholic president said "When this happens then the bitter memory of 1928 will begin to fade, and all that will remain will be the figure of Al Smith, large against the horizon, true, courageous, and honest, who in the words of the cardinal, served his country well, and having served his country well, nobly served his God".[17]

Smith won a majority of votes in the country's twelve largest cities. In 1924, Republicans had won the majority of votes in those cities by a compounded 1.6 million votes.[2] Smith's campaign brought significant Democratic gains in white ethnic neighborhoods in industrial cities such as Chicago and Boston, where Jews, Italians, Poles, and Irish voted in support of Smith. This helped to bring-about a political realignment which contributed to Franklin Delano Roosevelt's victory in the 1932 election.[2] Political scientist Samuel Lubell wrote, "Before the Roosevelt Revolution, there was an Al Smith revolution."[2]

University of Maryland historian Robert Chiles argues that the Smith campaign had a substantial impact on the Democratic party's policy platform, and that it contributed to Franklin Delano Roosevelt's New Deal.[18]

Further reading

References

- Caro, Robert A., The Power Broker: Robert Moses and the fall of New York, New York: Knopf, 1974. hardcover: ISBN 0-394-48076-7, Vintage paperback: ISBN 0-394-72024-5

- Golway, Terry. Machine Made: Tammany Hall and the Creation of Modern American Politics. W. W. Norton & Company.

- Timmerman, Bob (August 21, 2014). "A Catholic Runs for President: The Campaign of 1928 by Edmund A. Moore". allthepresidentsbooks.com. Bob Timmerman. Retrieved May 16, 2018.

- Webster's Unabridged Dictionary (Barnes & Nobles)2001

- "When a Catholic Terrified the Heartland".

- "Democratic National Convention 1928".

- Binning, William C.; Larry Eugene Esterly; Paul A. Sracic (1999). Encyclopedia of American parties, campaigns, and elections. p. 135. ISBN 978-0-313-30312-8.

- Ledbetter, Cal (August 24, 2008). "Joe T. Robinson and the 1928 presidential election". Arkansas Democrat-Gazette (Little Rock).

- reprinted 1977, John A. Ryan, "Religion in the Election of 1928," Current History, December 1928; reprinted in Ryan, Questions of the Day (Ayer Publishing, 1977) p.91

- Changing Party Coalitions: The Mystery of the Red State-blue State Alignment By Jerry F. Hough

- William E. Leuchtenburg, The Perils of Prosperity, 1914–32 (Chicago: University of Chicago, 1958) pp. 225–240.

- Webster's Unabridged Dictionary (Barnes & Nobles)2001

- "United States Electoral College Votes in 1928".

- "F.D.R.'s Rough Road to Nomination".

- "Rbert Moses 1888-1981".

- "1928 Presidential Election Results".

- "JFK speech at Al Smith Memorial Dinner".

- Chiles, Robert (2018-03-15). The Revolution of ’28: Al Smith, American Progressivism, and the Coming of the New Deal. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. ISBN 9781501705502.

.jpg)