1812 United States presidential election

The 1812 United States presidential election was the seventh quadrennial presidential election. It was held from Friday, October 30, 1812 to Wednesday, December 2, 1812. Taking place in the shadow of the War of 1812, incumbent Democratic-Republican President James Madison defeated DeWitt Clinton, who drew support from dissident Democratic-Republicans in the North as well as Federalists. It was the first presidential election to be held during a major war involving the United States.[2]

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

217 members of the Electoral College 109 electoral votes needed to win | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Turnout | 40.4%[1] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

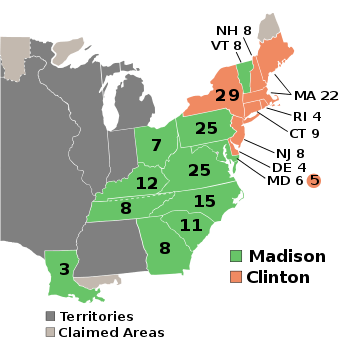

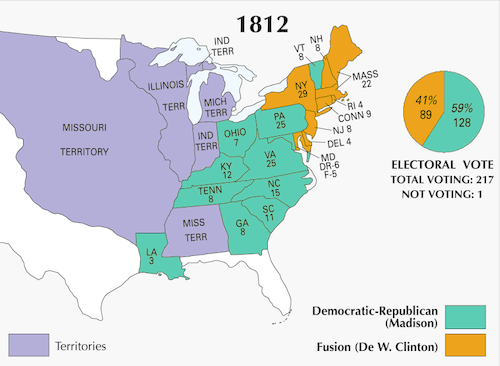

Presidential election results map. Green denotes states won by Madison and burnt orange denotes states won by Clinton. Numbers indicate the number of electoral votes cast by each state. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Northern Democratic-Republicans had long been dissatisfied by the Southern dominance of their party, and DeWitt Clinton's uncle, Vice President George Clinton, had unsuccessfully challenged Madison for the party's 1808 presidential nomination. While the May 1812 Democratic-Republican congressional nominating caucus re-nominated Madison, the party's New York caucus, also held in May, nominated Clinton for president. After the United States declared war on the United Kingdom in June 1812, Clinton sought to create a coalition of anti-war Democratic-Republicans and Federalists.[3] With Clinton in the race, the Federalist Party declined to formally put forth a nominee, hoping its members would vote for Clinton, but they did not formally endorse him, fearing that an explicit endorsement of Clinton would hurt the party's fortunes in other races. Federalist Jared Ingersoll of Pennsylvania became Clinton's de facto running mate.

Despite Clinton's success at attracting Federalist support, Madison was re-elected with 50.4 percent of the popular vote to his opponent's 47.6%, making the 1812 election the closest election up to that point in the popular vote. Clinton won the Federalist bastion of New England as well as three Mid-Atlantic states, but Madison dominated the South and took Pennsylvania. Though Madison won a relatively comfortable victory in the electoral vote, this was the most closely contested election held between 1800 and 1824.

Background

Residual military conflict resulting from the Napoleonic Wars in Europe had been steadily worsening throughout James Madison's first term, with the British and the French both ignoring the neutrality rights of the United States at sea by seizing American ships and looking for supposed British deserters in a practice known as impressment. The British provided additional provocations by impressing American seamen, maintaining forts within United States territory in the Northwest, and supporting American Indians at war with the United States in both the Northwest and Southwest.

Meanwhile, expansionists in the south and west of the United States coveted British Canada and Spanish Florida and wanted to use British provocations as a pretext to seize both areas. The pressure steadily built, with the result that the United States declared war on the United Kingdom on June 12, 1812. This occurred after Madison had been nominated by the Democratic-Republicans, but before the Federalists had made their nomination.

Nominations

Democratic-Republican Party nomination

| James Madison | Elbridge Gerry | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| for President | for Vice President | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4th President of the United States (1809–1817) |

9th Governor of Massachusetts (1810–1812) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Campaign | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Democratic-Republican candidates:

Many Democratic-Republicans in the northern states were unhappy over the perceived dominance of the presidency by the state of Virginia (three of the last four Presidents had been Virginians), and they wished instead to nominate one of their own rather than re-nominate Madison. Initially, these hopes were pinned upon Vice President George Clinton, but his poor health and advanced age (72) eliminated his chances. Even before Clinton's death on April 20, 1812, his nephew DeWitt Clinton was considered the preferred candidate to move against Madison by the northern Democratic-Republicans.

Hoping to forestall a serious movement against incumbent President James Madison and a division of the Democratic-Republican Party, some proposed making DeWitt Clinton the nominee for the Vice Presidency, taking over the same office his uncle now held. DeWitt was not opposed to the offer, but preferred to wait until after the conclusion of the New York caucus, which would not be held until after the Congressional Caucus had met, to finalize his decision. Early caucuses were held in the states of Virginia and Pennsylvania, both of which pledged their support to Madison. On May 18 a Democratic-Republican Congressional nominating caucus was held, and James Madison was formally nominated as the candidate of his party, though divisions were quite apparent; only 86 of the 134 Democratic-Republican Senators and Congressmen participated in the caucus. Seeking a northerner for a running mate (and with DeWitt Clinton remaining aloof), the caucus chose New Hampshire Governor John Langdon to balance the ticket. However Langdon declined due to his own advanced age, at the time 70 years. A second caucus nominated Governor Elbridge Gerry of Massachusetts for the Vice Presidency even though he was not much younger than Langdon at 68.

When the New York caucus did meet on May 29, it was dominated by anti-war Democratic-Republicans, and nominated DeWitt Clinton for the presidency almost unanimously.[3] Clinton's now open candidacy was opposed by many who, while not friends of James Madison, feared that Clinton was now apt to tear the Democratic-Republican party asunder. The matter of how to conduct his campaign also became a major problem for Clinton, especially with regards to the war with the British after June 12. Many of Clinton's supporters were war-hawks who advocated extreme measures to force the British into negotiations favorable to the United States, while Clinton knew he would have to appeal to Federalists to win, and they were almost wholly opposed to the war.[4]

| Presidential Ballot | Vice Presidential Ballot | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| James Madison | 81 | John Langdon | 64 |

| Abstaining | 1 | Elbridge Gerry | 16 |

| Scattering | 2 |

| Vice Presidential Ballot | |

|---|---|

| Elbridge Gerry | 74 |

| Scattering | 3 |

Federalist nomination

| Jared Ingersoll | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| for Vice President | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 5th & 11th Attorney General of Pennsylvania (1791–1800 & 1811–1816) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Federalist candidates:

Before Clinton entered the race as an alternative to President Madison, Chief Justice John Marshall was a favorite for the Federalist nomination, a relatively popular figure who could carry much of the Northeast while potentially taking Virginia and North Carolina as well. But with Clinton in the race, the Federalists would no longer be able to count on the electoral votes of New York, possibly throwing the election into the House of Representatives, dominated by Democratic-Republicans, where Madison would almost certainly be elected.

In the face of these facts, the Federalist party considered endorsing Clinton's candidacy for a time, but at their caucus in September it was decided that the party simply would not field a candidate that year and did not endorse Clinton. Though there was much support among the Federalists for Clinton, it was felt that openly endorsing him as the party's choice for president would damage his chances in states where the Federalists remained unpopular and drive away Democratic-Republicans who would normally be supportive of his candidacy. A Federalist caucus in Pennsylvania chose to nominate Jared Ingersoll, the Attorney General of the state, as Clinton's running-mate, a move Clinton decided to support considering the importance of Pennsylvania's electors.[4]

Straight-Federalist nomination

Straight-Federalist candidate:

While many Federalists were supportive of DeWitt Clinton's candidacy, others were not so keen, skeptical of Clinton's positions regarding the war and other matters. Rufus King, a former diplomat and Congressman, had led an effort at the September Caucus to nominate a Federalist ticket for the election that year, though he was ultimately unsuccessful. Still, some wished to enter King's name into the race under the Federalist label, and while very little came of it, it caused problems for the Clinton campaign in two states.

In the case of Virginia, Clinton was rejected entirely by the state Federalist Party, which instead chose to nominate Rufus King for President and William Richardson Davie for Vice President. The ticket would acquire about 27% of the vote in the state. In New York, with the Federalists having gained control of the state legislature that summer, it was planned that the Federalists would nominate a slate pledged to Rufus King now that they had the majority. However, a coalition of Democratic-Republicans and Federalists would defeat the motion and succeed in nominating a slate pledged to Clinton.[4]

General election

Campaign

The war heavily overshadowed the campaign.[2] Clinton continued his regional campaigning, adopting an anti-war stance in the Northeast (which was most harmed by the war), and a pro-war stance in the South and West. The election ultimately hinged on New York and Pennsylvania, and while Clinton took his home state, he failed to take Pennsylvania and thus lost the election.[2] Though Clinton lost, the election was the best showing for the Federalists since that of Adams, as the party made gains in Congress and kept the presidential election reasonably close. Clintonite Democratic-Republicans in many states refused to work with their Federalist counterparts (notably in Pennsylvania) and Clinton was generally regarded by most as the Federalist candidate, though he was not formally nominated by them.[4] Madison was the first of just four presidents in United States history to win re-election with a lower percentage of the electoral vote than in their prior elections, as Madison won 69.3% of the electoral vote in 1808, but only won 58.7% of the electoral vote in 1812. The other three were Woodrow Wilson in 1916, Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1940 and 1944 and Barack Obama in 2012. Additionally, Madison was the first of only five presidents to win re-election with a smaller percentage of the popular vote than in prior elections, although in 1812, only 6 of the 18 states chose electors by popular vote. The other four are Andrew Jackson in 1832, Grover Cleveland in 1892, Franklin Roosevelt in 1940 and 1944 and Obama in 2012.

Results

| Presidential candidate | Party | Home state | Popular vote(a), (b) | Electoral vote(c) |

Running mate | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Count | Percentage | Vice-presidential candidate | Home state | Electoral vote(c) | ||||

| James Madison (incumbent) | Democratic-Republican | Virginia | 140,431 | 50.4% | 128 | Elbridge Gerry | Massachusetts | 128 |

| DeWitt Clinton | Democratic-Republican | New York | 132,781 | 47.6% | 89 | Jared Ingersoll | Pennsylvania | 86 |

| Elbridge Gerry | Massachusetts | 3 | ||||||

| Rufus King | Federalist | New York | 5,574 | 2.0% | 0 | William R. Davie | North Carolina | 0 |

| Total | 278,786 | 100% | 217 | 217 | ||||

| Needed to win | 109 | 109 | ||||||

Source (Popular Vote): U.S. President National Vote. Our Campaigns. (February 10, 2006).

Source (Popular Vote): A New Nation Votes: American Election Returns 1787–1825[5]

Source (Electoral Vote): "Electoral College Box Scores 1789–1996". National Archives and Records Administration. Retrieved July 30, 2005.

(a) Only 9 of the 18 states chose electors by popular vote.

(b) Those states that did choose electors by popular vote had widely varying restrictions on suffrage via property requirements.

(c) One Elector from Ohio did not vote.

The split-party ticket of the Federalist DeWitt Clinton and the Democratic-Republican Elbridge Gerry was the result of two Federalist Electors in Gerry's home state of Massachusetts and one in New Hampshire voting for the New England region's favorite.

Electoral college selection

| Method of choosing electors | State(s) |

|---|---|

| Each Elector appointed by state legislature | |

| Each Elector chosen by voters statewide | |

| State is divided into electoral districts, with one Elector chosen per district by the voters of that district | |

|

Massachusetts |

In New Jersey, Federalists had just taken over the state legislature and decided to change the method of choosing electors from a general election to appointment by state legislature. Some towns, possibly too far away to get the news, or in open defiance of the switch, held elections anyway. These were not counted nor reported by the newspapers. In the unofficial elections, Madison received 1,672 votes while Clinton only received 2, suggesting these were protest votes (New Jersey was far more competitive than this at the time).[6]

See also

Notes

- While commonly labeled as the Federalist candidate, Clinton technically ran as a Democratic-Republican and was not nominated by the Federalist party itself, the latter simply deciding not to field a candidate. This did not prevent endorsements from state Federalist parties (such as in Pennsylvania), but he received the endorsement from the New York state Democratic-Republicans as well

References

- "National General Election VEP Turnout Rates, 1789-Present". United States Election Project. CQ Press.

- Sabato, Larry; Ernst, Howard (January 1, 2009). Encyclopedia of American Political Parties and Elections. Infobase Publishing. pp. 303–304.

- Morison, Samuel Eliot (1965). The Oxford History of the American People. New York: Oxford. p. 383.

- Schlesinger, Arthur M., Jr. (2002). History of American Presidential Elections, 1789–2001. Volume 1, 1789–1824. Chelsea House Publishers. pp. 249–272. ISBN 978-0791057131.

- "A New Nation Votes". elections.lib.tufts.edu.

- "A New Nation Votes". elections.lib.tufts.edu. p. See note one. Retrieved October 27, 2018.

Bibliography

- Boller, Paul F., Jr. (2004). Presidential Campaigns: From George Washington to George W. Bush. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 26–28. ISBN 978-0-19-516716-0.

- Siry, Steven Edwin (1985). "The Sectional Politics of "Practical Republicanism": De Witt Clinton's Presidential Bid, 1810–1812". Journal of the Early Republic. 5 (4): 441–462. doi:10.2307/3123061. JSTOR 3123061.

- A New Nation Votes: American Election Returns, 1787–1825

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to 1812 United States presidential election. |

- United States presidential election of 1812 at the Encyclopædia Britannica

- Presidential Election of 1812: A Resource Guide from the Library of Congress

- "A Historical Analysis of the Electoral College". The Green Papers. Retrieved March 20, 2005.

- Election of 1812 in Counting the Votes

.jpg)