Presidency of James Monroe

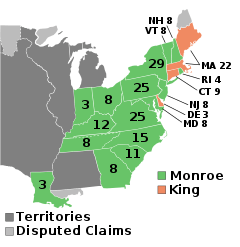

The presidency of James Monroe began on March 4, 1817, when James Monroe was inaugurated as President of the United States, and ended on March 4, 1825. Monroe, the fifth United States president, took office after winning the 1816 presidential election by an overwhelming margin over Federalist Rufus King. This election was the last in which the Federalists fielded a presidential candidate, and Monroe was unopposed in the 1820 presidential election. A member of the Democratic-Republican Party, Monroe was succeeded by Secretary of State John Quincy Adams.

| |

| Presidency of James Monroe | |

|---|---|

| March 4, 1817 – March 4, 1825 | |

| President | James Monroe |

| Cabinet | See list |

| Party | Democratic-Republican |

| Election | 1816, 1820 |

| Seat | White House |

.png) | |

| Dorsett seal | |

Monroe sought to eliminate political parties, and the Federalist Party faded as a national institution during his presidency. The Democratic-Republicans also stopped functioning as a unified political party, and the period during which Monroe served as president is often referred to as the "Era of Good Feelings" due to the lack of partisan conflict. Domestically, Monroe faced the Panic of 1819, the first major recession in the United States since the ratification of the Constitution. He supported many federally-funded infrastructure projects, but vetoed other projects due to constitutional concerns. Monroe supported the Missouri Compromise, which admitted Missouri as a slave state but excluded slavery in the remaining territories north of the parallel 36°30′ north.

In foreign policy, Monroe and Secretary of State Adams acquired East Florida from Spain with the Adams–Onís Treaty, realizing a long-term goal of Monroe and his predecessors. Reached after the First Seminole War, the Adams–Onís Treaty also solidified U.S. control over West Florida, established the western border of the United States, and included the cession of Spain's claims on Oregon Country. The Monroe administration also reached two treaties with Britain, marking a rapprochement between the two countries after the War of 1812. The Rush–Bagot Treaty demilitarized the U.S. border with British North America, while the Treaty of 1818 settled some boundary disputes and provided for the joint settlement of Oregon Country. Monroe was deeply sympathetic to the revolutionary movements in Latin America and opposed European influence in the region. In 1823, Monroe promulgated the Monroe Doctrine, which declared that the U.S. would remain neutral in European affairs, but would not accept new colonization of Latin America by European powers.

In the 1824 presidential election, four members of the Democratic-Republican Party sought to succeed Monroe, who remained neutral among the candidates. Adams emerged as the victor over General Andrew Jackson and Secretary of the Treasury William H. Crawford in a contingent election. Polls of historians and political scientists have generally ranked Monroe as an above-average president.

Election of 1816

Monroe's war-time leadership in the Madison administration had established him as the Democratic-Republican heir apparent, but not all party leaders supported Monroe's candidacy in the lead-up to the 1816 presidential election. Secretary of the Treasury William H. Crawford had the support of numerous Southern and Western Congressmen, many of whom were wary of Madison and Monroe's support for the establishment of the Second Bank of the United States. New York Democratic-Republicans resisted the possibility of another Virginian winning the presidency, and they backed the candidacy of Governor Daniel D. Tompkins. Though Crawford desired the nomination, he did not strongly oppose Monroe's candidacy, as he hoped to position himself to succeed Monroe in 1820 or 1824. In the congressional nominating caucus held in March 1816, Monroe defeated Crawford in a 65-to-54 vote, becoming his party's presidential nominee. Tompkins won the party's vice presidential nomination.[1]

The moribund Federalist Party nominated Rufus King as their presidential nominee, but the Federalists offered little opposition following the conclusion of the War of 1812, which they had opposed. Some opponents of Monroe tried to recruit DeWitt Clinton, Madison's opponent in the 1812 election, but Clinton declined to enter the race.[2] Monroe received 183 of the 217 electoral votes, winning every state but Massachusetts, Connecticut, and Delaware.[3] In the concurrent congressional elections, Democratic-Republicans picked up several seats in the House of Representatives, leaving them with control of over three quarters of the chamber.[4] Monroe was the last president called a Founding Father of the United States, and also the last president of the "Virginia dynasty", a term sometimes used to describe the fact that four of the nation's first five presidents were from Virginia.[5]

Administration

| The Monroe Cabinet | ||

|---|---|---|

| Office | Name | Term |

| President | James Monroe | 1817–1825 |

| Vice President | Daniel D. Tompkins | 1817–1825 |

| Secretary of State | Richard Rush | 1817 |

| John Quincy Adams | 1817–1825 | |

| Secretary of the Treasury | William H. Crawford | 1817–1825 |

| Secretary of War | John C. Calhoun | 1817–1825 |

| Attorney General | Richard Rush | 1817 |

| William Wirt | 1817–1825 | |

| Secretary of the Navy | Benjamin Williams Crowninshield | 1817–1818 |

| Smith Thompson | 1819–1823 | |

| Samuel L. Southard | 1823–1825 | |

Monroe appointed a geographically-balanced cabinet, through which he led the executive branch.[6] At Monroe's request, Crawford continued to serve as Treasury Secretary. Monroe also chose to retain Benjamin Crowninshield of Massachusetts as Secretary of the Navy and Richard Rush of Pennsylvania as Attorney General. Recognizing Northern discontent at the continuation of the Virginia dynasty, Monroe chose John Quincy Adams of Massachusetts to fill the prestigious post of Secretary of State, making Adams the early favorite to eventually succeed Monroe as president. An experienced diplomat, Adams had abandoned the Federalist Party in 1807 in support of Thomas Jefferson's foreign policy, and Monroe hoped that the appointment of Adams would encourage the defection of more Federalists. Monroe offered the position of Secretary of War to Henry Clay of Kentucky, but Clay was only willing to serve in the cabinet as Secretary of State. Monroe's decision to appoint Adams to the latter position alienated Clay, and Clay would oppose many of the administration's policies. After General Andrew Jackson and Governor Isaac Shelby declined appointment as Secretary of War, Monroe turned to South Carolina Congressman John C. Calhoun, leaving the cabinet without a prominent Westerner. In late 1817, Rush was appointed as the ambassador to Britain, and William Wirt succeeded him as Attorney General.[7] With the exception of the Crowninshield, Monroe's cabinet appointees remained in place for the remainder of his presidency.[8]

Judicial appointments

In September 1823, Secretary of the Navy Smith Thompson received a recess appointment from President Monroe to a seat on the Supreme Court that had been vacated by Henry Brockholst Livingston. Officially nominated for the same seat on December 5, 1823, he was confirmed by the United States Senate on December 9.[9] Thompson was on good personal terms with Monroe, had a long record of public service as a jurist and a public official, and, like Livingston, hailed from the state of New York. Monroe also considered Senator Martin Van Buren and jurists Ambrose Spencer and James Kent for the nomination.[10] Thompson was Monroe's lone appointment to the Supreme Court, though Monroe also appointed 21 judges to United States district courts during his presidency.

Domestic affairs

Democratic-Republican Party dominance

Like all four of his predecessors, Monroe believed that the existence of political parties was harmful to the United States, and he made the elimination of political parties a major goal of his presidency.[11] He sought to strengthen the Democratic-Republican Party by avoiding divisive policies and welcoming ex-Federalists into the fold, with the ultimate aim being the dissolution of the Federalists.[12] Monroe made two long national tours to build national trust. At Boston, his 1817 visit was hailed as the beginning of an "Era of Good Feelings." Frequent stops on these tours allowed innumerable ceremonies of welcome and expressions of good will.[13] Monroe was seen by more Americans than any previous president, and his travels were detailed in the local and national press.[14] The Federalists failed to develop a unified national program, and Federalist candidates frequently campaigned on local rather than national issues.[15] The Federalists maintained their organizational integrity in Delaware and a few localities, but lacked influence in national politics. Lacking serious opposition, the Democratic-Republican Party's congressional caucus stopped meeting, and for practical purposes the Democratic-Republican Party stopped operating.[13]

Panic of 1819

Two years into his presidency, Monroe faced an economic crisis known as the Panic of 1819, the first major depression to hit the country since the ratification of the Constitution in 1788.[16] The panic stemmed from declining imports and exports, and sagging agricultural prices[17] as global markets readjusted to peacetime production and commerce after the War of 1812 and the Napoleonic Wars.[18][19] The severity of the economic downturn in the U.S. was compounded by excessive speculation in public lands,[20] fueled by the unrestrained issue of paper money from banks and business concerns.[21][22] The Second Bank of the United States (B.U.S.) failed to restrict inflation until late 1818, when the directors of the B.U.S. took overdue steps to curtail credit. Branches were ordered to accept no bills but their own, to present all state bank notes for payment immediately, and to renew no personal notes or mortgages.[23] These contractionary fiscal policies backfired, as they undermined public confidence in banks and contributed to the onset of the panic.[24]

Monroe had little control over economic policy; in the early 19th century, such power rested largely with the states and the B.U.S.[17] As the panic spread, Monroe declined to call a special session of Congress to address the economy. When Congress finally reconvened in December 1819, Monroe requested an increase in the tariff but declined to recommend specific rates.[25] Congress would not raise tariff rates until the passage of the Tariff of 1824.[26] The panic resulted in high unemployment, an increase in bankruptcies and foreclosures,[17][27] and provoked popular resentment against banking and business enterprises.[28][29]

Popular resentment towards the national bank motivated the state of Maryland to implement a tax on the national bank's branch in that state.[30] Shortly afterwards, the Supreme Court handed down its decision in McCulloch v. Maryland. In a major defeat for states' rights advocates, the Supreme Court forbade states from taxing B.U.S. branches.[23] In his majority opinion, Chief Justice John Marshall articulated a broad reading of the Necessary and Proper Clause, holding that the Constitution granted Congress powers that were not expressly defined.[31] The decision fed the popular disdain for the B.U.S. and aroused fears about the growing reach of federal power.[23]

Missouri Compromise

Beginning in 1818, Clay and territorial delegate John Scott sought the admission of Missouri Territory as a state. The House failed to act on the bill before Congress adjourned in April, but took up the issue again after Congress reconvened in December 1818.[32] During these proceedings, Congressman James Tallmadge, Jr. of New York "tossed a bombshell into the Era of Good Feelings"[33] by offering amendments (known collectively as the Tallmadge Amendment) prohibiting the further introduction of slaves into Missouri, and requiring that all children subsequently born therein of slave parents should be free at the age of twenty-five years.[34] The amendments sparked the most significant national slavery debate since the ratification of the Constitution,[6] and instantly exposed the sectional polarization over the issue of slavery.[35][36]

Northern Democratic-Republicans formed a coalition across partisan lines with remnants of the Federalists in support of the exclusion of slavery from Missouri and all future states and territories, while Southern Democratic-Republicans were almost unanimously against such a restriction.[37] Northerners focused their arguments on the immorality of slavery, while Southerners focused their attacks on the purported unconstitutionality of banning slavery within a state.[38] A few southerners such as former President Jefferson, argued that the "diffusion" of slaves into the west would make gradual emancipation more feasible. Most southern whites, however, favored diffusion because it would help prevent slave rebellions. Both sides also recognized that the status of slavery in Missouri could have important consequences on the balance between slave states and free states in the United States Senate.[39]

The bill, with Tallmadge’s amendments, passed the House in a mostly sectional vote, though ten free state congressmen joined with the slave state congressmen in opposing at least one of the provisions of the bill.[40] The measure then went to the Senate, where both amendments were rejected.[36] A House–Senate conference committee was unable to resolve the disagreements on the bill, and so the whole measure was lost.[41] Congress took up the issue again when it reconvened in December 1819.[42] Monroe, himself a slaveowner, threatened to veto any bill that restricted slavery in Missouri.[43] He also supported the efforts of Senator James Barbour and other Southern Congressmen to win the admission of Missouri as a slave state by threatening to withhold statehood from Maine, which was at the time a part of Massachusetts.[44]

In February 1820, Congressman Jesse B. Thomas of Illinois proposed a compromise: Missouri would be admitted as a slave state, but slavery would be excluded in the remaining territories north of the parallel 36°30′ north. Like many other Southern leaders, Monroe came to view Thomas's proposal as the least damaging outcome for southern slaveholders.[45] With assistance from national bank president Nicholas Biddle, Monroe used his influence and power of patronage to line up support behind Thomas's proposal.[21] The Senate passed a bill that included Thomas's territorial restriction on slavery, and which also provided for the admittance of Maine and Missouri.[46] The House approved the Senate bill in a narrow vote, and after deliberating with his cabinet, Monroe signed the legislation into law in April 1820.[47]

The question of the final admission of Missouri came up again in November 1820. The Missouri constitution included a provision that barred free blacks from entering the state, which many northerners deemed unconstitutional.[48] The dispute over Missouri affected the 1820 presidential election, and Congress reported electoral vote totals both with and without Missouri's votes.[49] Through the influence of Clay, an act of admission was finally passed, upon the condition that the exclusionary clause of the Missouri constitution should "never be construed to authorize the passage of any law" impairing the privileges and immunities of any U.S. citizen. This deliberately ambiguous provision is sometimes known as the Second Missouri Compromise.[50] It was a bitter pill for many to swallow and the admission of new states as free or slave became a major issue until the abolition of slavery.[51]

Aside from settling the issue of Missouri's statehood, the Missouri Compromise had several important effects. It helped forestall a split in the Democratic-Republican Party along sectional lines at a time when the Federalists offered little effective opposition, and set a precedent whereby free states and slave states were admitted in pairs to avoid upsetting the balance of the Senate. The compromise also elevated the stature of both Henry Clay and the United States Senate. Perhaps most importantly, the Missouri Compromise indicated a shift away from gradual emancipation, a policy that had once held wide support among Southern leaders.[52] The planned slave revolt of Denmark Vesey, who was captured and executed in 1822, further contributed to a hardening of pro-slavery attitudes in the South during Monroe's tenure as president.[53][54]

Internal improvements

As the United States continued to grow, many Americans advocated the construction of a system of internal improvements to help the country develop. Federal assistance for such projects evolved slowly and haphazardly—the product of contentious congressional factions and an executive branch that was concerned about the constitutionality of federal involvement with such projects.[55] Monroe believed that the young nation needed to improve its infrastructure to grow and thrive economically, but also worried about the constitutionality of a federal role in the construction, maintenance, and operation of a national transportation system.[17] Monroe repeatedly urged Congress to pass an amendment allowing Congress the power to finance internal improvements, but Congress never acted on his proposal. Many congressmen believed that the Constitution already allowed the federal financing of internal improvements.[56]

The United States had begun construction on the National Road in 1811, and by the end of 1818 it linked the Ohio River and the Potomac River.[57] In 1822, Congress passed a bill authorizing the collection of tolls to finance repairs on the road. Adhering to his stated position regarding internal improvements, Monroe vetoed the bill.[56] In an elaborate essay, Monroe set forth his constitutional views on the subject. Congress might appropriate money, he admitted, but it could not undertake the actual construction of national works nor assume jurisdiction over them.[58] In 1823, Monroe proposed that Congress work with the states to build a system of canals to connect the rivers leading to the Atlantic Ocean with the western territories of the United States, and he eventually signed a bill providing for investment in the Chesapeake & Delaware Canal Company. Monroe's call for canals was inspired by the impending completion of the Erie Canal, which would link New York City with the Great Lakes.[59]

In 1824, the Supreme Court ruled in Gibbons v. Ogden that the Constitution's Commerce Clause gave the federal government broad authority over interstate commerce. Shortly thereafter, Congress passed two important laws that, together, marked the beginning of the federal government's continuous involvement in civil works. The General Survey Act authorized the president to have surveys made of routes for roads and canals "of national importance." The president assigned responsibility for the surveys to the Army Corps of Engineers. The second act, passed a month later, appropriated $75,000 to improve navigation on the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers by removing sandbars, snags, and other obstacles. Subsequently, the act was amended to include other rivers such as the Missouri.[55]

Other issues and events

In the years before Monroe took office, a movement supporting the colonization of Africa by free blacks became increasingly popular. Congressman Charles F. Mercer of Virginia and Reverend Robert Finley of New Jersey established the American Colonization Society (ACS) to further the goal of African colonization. Most adherents of the society supported colonization to provide for the gradual emancipation of slaves and diversify the Southern economy, but the ACS also appealed to pro-slavery Southerners whose primarily goal was the removal of free blacks from the country. The ACS attracted several prominent supporters, including Madison, Associate Justice Bushrod Washington, and Henry Clay. In 1819, the Monroe administration agreed to provide some funding to the ACS, and, much like the national bank, the society operated as a public-private partnership. The U.S. Navy helped the ACS establish a colony in West Africa, which would be adjacent to Sierra Leone, another colony that had been established for free blacks. The new colony was named Liberia, and Liberia's capital took the name of Monrovia in honor of President Monroe. By the 1860s, over ten thousand African Americans had migrated to Liberia. Though initially intended to be a permanent U.S. colony, Liberia would declare independence in 1847.[60]

Monroe took a close interest in the Western American frontier, which was overseen by Secretary of War Calhoun. Calhoun organized an expedition to the Yellowstone River to extend American influence in and knowledge of the northwest region of the Louisiana Purchase.[61] The expedition suffered several setbacks, but the efforts of scientists such as Edwin James advanced U.S. knowledge of the flora and fauna of the region.[62]

The federal government had taken control of the Yazoo lands from Georgia in the Compact of 1802; as part of that agreement, President Jefferson promised to remove Native Americans from the region.[63] Georgians pressed Monroe to remove the remaining Native Americans to regions west of the Mississippi River, but the Native Americans rejected the Monroe administration's offers to purchase their land. As Monroe was unwilling to forcibly evict the Native American tribes, he took no major actions regarding Indian removal.[64]

Foreign affairs

Treaties with Great Britain

Near the beginning of Monroe's first term, the administration negotiated two important accords with Great Britain that resolved border disputes held over from the War of 1812.[65] The Rush-Bagot Treaty, signed in April 1817, regulated naval armaments on the Great Lakes and Lake Champlain, demilitarizing the border between the U.S. and British North America.[66] The Treaty of 1818, signed in October 1818, fixed the present Canada–United States border from Minnesota to the Rocky Mountains at the 49th parallel.[65] Britain ceded all of Rupert's Land south of the 49th parallel and east of the Continental Divide, including all of the Red River Colony south of that latitude, while the U.S. ceded the northernmost edge of the Missouri Territory above the 49th parallel. The treaty also established a joint U.S.–British occupation of Oregon Country for the next ten years.[65] Together, the Rush-Bagot Treaty and the Treaty of 1818 marked an important turning point in Anglo–American and American–Canadian relations, although they did not solve all outstanding issues.[67] The easing of tensions contributed to expanded trade, particularly cotton, and played a role in Britain's decision to refrain from becoming involved in the First Seminole War.[68]

Spanish Florida

Seminole Wars

Spain faced a troubling colonial situation after the Napoleonic Wars, as revolutionaries in Central America and South America were beginning to demand independence.[69] The United States had taken control of part of West Florida in 1810, and, by the time Monroe took office, American settlers also encroached on Spanish territory in East Florida and New Spain. With a minor military presence in the Floridas, Spain was unable to restrain the Seminole Indians, who routinely conducted cross-border raids on American villages and farms and protected slave refugees from the United States. Acquisition of the Floridas was a long-held goal of Monroe, Adams, and other leading Democratic-Republicans, as authority over the region would consolidate U.S. control of its southeastern lands against British and Spanish influence.[70]

To stop the Seminole from raiding Georgia settlements and offering havens for runaway slaves, the U.S. Army led increasingly frequent incursions into Spanish territory. In early 1818, Monroe ordered General Andrew Jackson to the Georgia–Florida border to defend against Seminole attacks. Monroe authorized Jackson to attack Seminole encampments in Spanish Florida, but not Spanish settlements themselves.[71] In what became known as the First Seminole War, Jackson crossed over into Spanish territory and attacked the Spanish fort at St. Marks.[72] He also executed two British subjects whom he accused of having incited the Seminoles to raid American settlements.[73] Jackson claimed that the attack on the fort was necessary as the Spanish were providing aid to the Seminoles. After taking the fort St. Marks, Jackson moved on the Spanish position at Pensacola, capturing it in May 1818.[74]

In a letter to Jackson, Monroe reprimanded the general for exceeding his orders, but also acknowledged that Jackson may have been justified given the circumstances in the war against the Seminoles.[75] Though he had not authorized Jackson's attacks on Spanish posts, Monroe recognized that Jackson's campaign left the United States with a stronger hand in ongoing negotiations over the purchase of the Floridas, as it showed that Spain was unable to defend its territories.[76] The Monroe administration restored the Floridas to Spain, but requested that Spain increase efforts to prevent Seminole raids.[77] Some in Monroe's cabinet, including Secretary of War John Calhoun, wanted the aggressive general court-martialed, or at least reprimanded. Secretary of State Adams alone took the ground that Jackson's acts were justified by the incompetence of Spanish authority to police its own territory,[73] arguing that Spain had allowed East Florida to become "a derelict open to the occupancy of every enemy, civilized or savage, of the United States, and serving no other earthly purpose than as a post of annoyance to them."[78] His arguments, along with the restoration of the Floridas, convinced the British and Spanish not to retaliate against the United States for Jackson's conduct.[79]

News of Jackson's exploits caused consternation in Washington and ignited a congressional investigation. Clay attacked Jackson's actions and proposed that his colleagues officially censure the general.[80] Even many members of Congress who tended to support Jackson worried about the consequences of allowing a general to make war without the consent of Congress.[81] In reference to popular generals who had taken power through military force, Speaker of the House Henry Clay urged his fellow congressmen to "remember that Greece had her Alexander, Rome her Julius Caesar, England her Cromwell, France her Bonaparte."[82] Dominated by Democratic-Republicans, the 15th Congress was generally expansionist and supportive of the popular Jackson. After much debate, the House of Representatives voted down all resolutions that condemned Jackson, thus implicitly endorsing the military intervention.[83] Jackson's actions in the First Seminole War would be the subject of ongoing controversy in subsequent years, as Jackson claimed that Monroe had secretly ordered him to attack the Spanish settlements, a claim that Monroe denied.[74]

Acquisition of Florida

Negotiations over the purchase of the Floridas began in early 1818.[84] Don Luis de Onís, the Spanish Minister at Washington, suspended negotiations after Jackson attacked Spanish settlements,[85] but he resumed his talks with Secretary of State Adams after the U.S. restored the territories.[86] On February 22, 1819, Spain and the United States signed the Adams–Onís Treaty, which ceded the Floridas in return for the assumption by the United States of claims of American citizens against Spain to an amount not exceeding $5,000,000. The treaty also contained a definition of the boundary between Spanish and American possessions on the North American continent. Beginning at the mouth of the Sabine River, the line ran along that river to the 32nd parallel, then due north to the Red River, which it followed to the 100th meridian, due north to the Arkansas River, and along that river to its source, then north to the 42nd parallel, which it followed to the Pacific Ocean. The United States renounced all claims to the lands west and south of this boundary, while Spain surrendered its claim to Oregon Country.[85] Spanish delay in relinquishing control of the Floridas led some congressmen to call for war, but Spain peacefully transferred control of the Floridas in February 1821.[87]

Latin America

Engagement

Monroe was deeply sympathetic to the Latin American revolutionary movements against Spain. He was determined that the United States should never repeat the policies of the Washington administration during the French Revolution, when the nation had failed to demonstrate its sympathy for the aspirations of peoples seeking to establish republican governments. He did not envisage military involvement but only the provision of moral support, as he believed that a direct American intervention would provoke other European powers into assisting Spain.[88] Despite his preferences, Monroe initially refused to recognize the Latin American governments due to ongoing negotiations with Spain over Florida.[89]

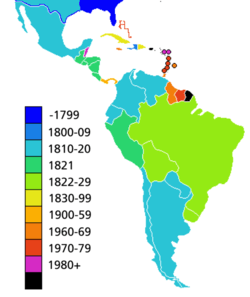

In March 1822, Monroe officially recognized the countries of Argentina, Peru, Colombia, Chile, and Mexico.[65] Secretary of State Adams, under Monroe's supervision, wrote the instructions for the ambassadors to these new countries. They declared that the policy of the United States was to uphold republican institutions and to seek treaties of commerce on a most-favored-nation basis. The United States would support inter-American congresses dedicated to the development of economic and political institutions fundamentally different from those prevailing in Europe. Monroe took pride as the United States was the first nation to extend recognition and to set an example to the rest of the world for its support of the "cause of liberty and humanity".[88] In 1824, the U.S. and Gran Colombia reached the Anderson–Gual Treaty, a general convention of peace, amity, navigation, and commerce that represented the first treaty the United States entered into with another country in the Americas.[90][91] Between 1820 and 1830, the number of U.S. consuls assigned to foreign countries would double, with much of that growth coming in Latin America. These consuls would help merchants expand U.S. trade in the Western Hemisphere.[92]

Monroe Doctrine

The British had a strong interest in ensuring the demise of Spanish colonialism, as the Spanish followed a mercantilist policy that imposed restrictions on trade between Spanish colonies and foreign powers. In October 1823, Ambassador Rush informed Secretary of State Adams that Foreign Secretary George Canning desired a joint declaration to deter any other power from intervening in Central and South America. Canning was motivated in part by the restoration of King Ferdinand VII of Spain by France. Britain feared that either France or the "Holy Alliance" of Austria, Prussia, and Russia would help Spain regain control of its colonies, and sought American cooperation in opposing such an intervention. Monroe and Adams deliberated the British proposal extensively, and Monroe conferred with former presidents Jefferson and Madison.[93]

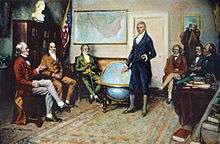

Monroe was at first inclined to accept Canning's proposal, and Madison and Jefferson both shared this preference.[93] Adams, however, vigorously opposed cooperation with Great Britain, contending that a statement of bilateral nature could limit U.S. expansion. Additionally, Adams and Monroe shared a reluctance to appear as a junior partner in any alliance.[94] Rather than responding to Canning's alliance offer, Monroe decided to issue a statement regarding Latin America in his 1823 Annual Message to Congress. In a series of meetings with the cabinet, Monroe formulated his administration's official policy regarding European intervention in Latin America. Adams played a major role in these cabinet meetings, and the Secretary of State convinced Monroe to avoid antagonizing the members of the Holy Alliance with unduly belligerent language.[95]

Monroe's annual message was read by both houses of Congress on December 2, 1823. In it, he articulated what became known as the Monroe Doctrine.[96] The doctrine reiterated the traditional U.S. policy of neutrality with regard to European wars and conflicts, but declared that the United States would not accept the recolonization of any country by its former European master. Monroe stated that European countries should no longer consider the Western Hemisphere open to new colonization, a jab aimed primarily at Russia, which was attempting to expand its colony on the northern Pacific Coast. At the same time, Monroe avowed non-interference with existing European colonies in the Americas.[65][88]

The Monroe Doctrine was well received in the United States and Britain, while Russia, French, and Austrian leaders privately denounced it.[97] The European powers knew that the U.S. had little ability to back up the Monroe Doctrine with force, but the United States was able to "free ride" on the strength of the British Royal Navy.[65] Nonetheless, the issuance of the Monroe Doctrine displayed a new level of assertiveness by the United States in international relations, as it represented the country's first claim to a sphere of influence. It also marked the country's shift in psychological orientation away from Europe and towards the Americas. Debates over foreign policy would no longer center on relations with Britain and France, but would instead focus on western expansion and relations with Native Americans.[98]

Russo-American Treaty

In the 18th century, Russia had established Russian America on the Pacific coast. In 1821, Tsar Alexander I issued an edict declaring Russia's sovereignty over the North American Pacific coast north of the 51st parallel north. The edict also forbade foreign ships to approach within 115 miles of the Russian claim. Adams strongly protested the edict, which potentially threatened both the commerce and expansionary ambitions of the United States. Seeking favorable relations with the U.S., Alexander agreed to the Russo-American Treaty of 1824. In the treaty, Russia limited its claims to lands north of parallel 54°40′ north, and also agreed to open Russian ports to U.S. ships.[99]

States admitted to the Union

Five new states were admitted to the Union while Monroe was in office:

- Mississippi – December 10, 1817[100]

- Illinois – December 3, 1818[101]

- Alabama – December 14, 1819[102]

- Maine – March 15, 1820[103]

Maine is one of 3 states set off from existing states (Kentucky and West Virginia are the others). The Massachusetts General Court passed enabling legislation on June 19, 1819 separating the "District of Maine" from the rest of the State (an action approved by the voters in Maine on July 19, 1819 by 17,001 to 7,132); then, on February 25, 1820, passed a follow-up measure officially accepting the fact of Maine's imminent statehood.[104] - Missouri – August 10, 1821[105]

Elections

Election of 1820

During James Monroe’s first term, the country had suffered an economic depression and slavery had emerged as a divisive issue. Despite these problems,[106] the collapse of the Federalists left Monroe with no organized opposition at the end of his first term, and he ran for reelection unopposed,[107] the only president other than George Washington to do so. A single elector from New Hampshire, William Plumer, cast a vote for John Quincy Adams, preventing a unanimous vote in the Electoral College.[107] Plumer also refused to vote for Daniel Tompkins for Vice President, whom he considered "grossly intemperate."[108] His dissent was joined by several Federalist electors who, although pledged to vote for Tompkins, voted for someone else for vice president.[109]

Election of 1824

The Federalist Party had nearly collapsed by the end of Monroe's two terms, and all of the major presidential candidates in 1824 were members of the Democratic-Republican Party. Secretary of State John Quincy Adams, Secretary of War John C. Calhoun, Secretary of the Treasury William H. Crawford, and Speaker of the House Henry Clay each entered the race with strong followings.[110] Crawford favored state sovereignty and strict constructionism, while Calhoun, Clay, and Adams all embraced internal improvements, high tariffs, and the national bank.[111] As 1824 approached, General Andrew Jackson jumped into the race, motivated in large part by his anger over Clay and Crawford's denunciations of his actions in Florida.[110] The congressional nominating caucus had decided upon previous Democratic-Republican presidential nominees, but had become largely discredited by 1824. Candidates were instead nominated by state legislatures or nominating conventions.[112] With three cabinet members in the race, Monroe remained neutral.[113]

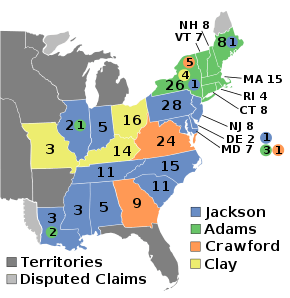

Seeing Jackson's strength, Calhoun dropped out of the presidential race and instead sought the vice presidency. The remaining candidates relied heavily on regional strength. Adams was popular in New England, Clay and Jackson were strong in the West, and Jackson and Crawford competed for the South, despite the latter's health problems.[114] In the 1824 presidential election, Jackson won a plurality in the Electoral College, taking 99 of the 261 electoral votes, while Adams won 84, Crawford won 41, and Clay took 37. As no candidate won a majority of the electoral vote, the House was required to hold a contingent election under the terms of the Twelfth Amendment. The House would decide among the top three electoral vote winners, with each state's delegation having one vote; Clay was thus not eligible to be elected by the House.[114]

Jackson's policy views were unclear, but Clay had been outraged by Jackson's actions in Florida, and he feared what Jackson would do in office. He also shared many policies with Adams. Adams and Clay met prior to the contingent election, and Clay agreed to support Adams.[115] On February 9, 1825, Adams became the second president elected by the House of Representatives (after Thomas Jefferson in 1801), when he won the contingent election on the first ballot, taking 13 of the 24 state delegations.[116]

Historical reputation

Historian Harry Ammon says that as president Monroe gave up his previous partisanship, and fostered an era free of party animosity. Ammon continues:

- He was a moderate nationalist, accepting the tariff and the Bank of the United States as essential to the well-being of the nation. Only on internal improvements did he adhere to the traditional strict constructionism of his party....Repudiating party loyalty as a means of executive leadership, Monroe sought to execute his policies by relying on the substantial congressional following of three members of his cabinet: John Quincy Adams (state), William H. Crawford (treasury) and John C. Calhoun (war).... [He and Adams] sought to develop a foreign policy which would not only be appropriate for a republic and realize America's national interests but also obtain from the European powers a degree of respect previously denied the United States.[117]

Ammon argues that politics undermined his second term: "Many of his most favored projects, such as his plans to construct stronger coastal defenses and the Anglo-American Treaty of 1823 to prohibit the international slave trade, fell victim of presidential political rivalries.[118]

Monroe turned the nation away from European affairs and towards domestic issues. His presidency oversaw the settlement of many longstanding boundary issues through an accommodation with Britain and the acquisition of Florida. Monroe also helped resolve sectional tensions through his support of the Missouri Compromise and by seeking support from all regions of the country.[119] Political scientist Fred Greenstein argues that Monroe was a more effective executive than some of his better-known predecessors, including Madison and John Adams.[14]

Polls of historians and political scientists tend to rank Monroe as an above average president. A 2018 poll of the American Political Science Association’s Presidents and Executive Politics section ranked Monroe as the eighteenth best president.[120] A 2017 C-Span poll of historians ranked Monroe as the thirteenth best president.[121]

See also

References

- Cunningham 1996, pp. 15–18.

- Cunningham 1996, pp. 18–19.

- Unger 2009, pp. 258–260

- Cunningham 1996, p. 51.

- González, Jennifer González (January 4, 2016). "Virginia Dynasty: James Madison". In custodia legis: Law Librarians of Congress. Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress. Retrieved June 28, 2018.

- Cunningham, pp. 28–29.

- Cunningham 1996, pp. 21–23.

- Cunningham, pp. 118–119.

- "Biographical Directory of Federal Judges: Thompson, Smith". History of the Federal Judiciary. Federal Judicial Center. Retrieved February 16, 2017.

- Abraham, 2008, pp. 73–74.

- Howe, pp. 93–94.

- Cunningham 1996, pp. 19–21.

- Arthur Meier Schlesinger, Jr., ed. History of U.S. political parties: Volume 1 (1973) pp. 24–25, 267

- Greenstein 2009.

- Howe, p. 95.

- Cunningham, p. 81.

- "James Monroe: Domestic Affairs". Miller Center of Public Affairs, University of Virginia. Retrieved February 22, 2017.

- Ammon, p. 462.

- Wilentz, 2005, pp. 208, 215.

- Dangerfield, 1965, pp. 82, 84, 86.

- Wilentz, 2005, p. 206.

- Dangerfield, 1965, p. 87.

- Morison, pp. 403.

- Howe, pp. 142–144.

- Cunningham, pp. 84–86.

- Cunningham, p. 167.

- Dangerfield, 1965, pp. 82, 84, 85.

- Dangerfield, 1965, pp. 89-90.

- Hammond, Bray (1957). Banks and Politics in America, from the Revolution to the Civil War. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Howe, pp. 144–145.

- Howe, pp. 144–146.

- Cunningham, pp. 87–88.

- Howe, p. 147.

- Morison, pp. 404-405.

- Wilentz, 2004, p. 376: "[T]he sectional divisions among the Jeffersonian Republicans…offers historical paradoxes…in which hard-line slaveholding Southern Republicans rejected the egalitarian ideals of the slaveholder [Thomas] Jefferson while the antislavery Northern Republicans upheld them – even as Jefferson himself supported slavery's expansion on purportedly antislavery grounds.

- Dangerfield, 1965, p. 111.

- Wilentz, 2004, pp. 380, 386.

- Cunningham, pp. 88–89.

- Howe, pp. 148–150.

- Cunningham, pp. 89–90.

- Wilentz, 2004, p. 380.

- Cunningham, pp. 92–93.

- Cunningham, pp. 93–95, 101.

- Cunningham, pp. 97–98.

- Cunningham, pp. 101–103.

- Cunningham, pp. 102–103.

- Cunningham, pp. 103–104.

- Cunningham, pp. 108–109.

- Howe, p. 156.

- Dixon, 1899 pp. 116–117

- "Biography: 5. James Monroe". The American Experience: The Presidents. Corporation for Public Broadcasting. Retrieved February 21, 2017.

- Howe, pp. 148–149, 154–155.

- Howe, pp. 160–163.

- John Craig Hammond, "President, Planter, Politician: James Monroe, the Missouri Crisis, and the Politics of Slavery." Journal of American History 105.4 (2019): 843-867. online.

- "The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers: A Brief History Improving Transportation". United States Army Corps of Engineers. Retrieved February 26, 2017.

- Cunningham, pp. 165–166.

- Howe, p. 207.

- Johnson, pp. 309–310.

- Cunningham, pp. 166–167.

- Howe, pp. 260–264.

- Cunningham, pp. 75–76.

- Cunningham, pp. 79–81.

- Cunningham, p. 114.

- Cunningham, pp. 173–174.

- "James Monroe: Foreign Affairs". Miller Center of Public Affairs, University of Virginia. Retrieved February 25, 2017.

- Uphaus-Conner, Adele (April 20, 2012). "Today in History: Rush-Bagot Treaty Signed". James Monroe Museum and Memorial Library University of Mary Washington. Retrieved February 25, 2017.

- "Milestones: 1801–1829: Rush-Bagot Pact, 1817 and Convention of 1818". Office of the Historian, Bureau of Public Affairs United States Department of State. Retrieved February 25, 2017.

- Howe, p. 106.

- Cunningham, p. 23.

- Herring, pp. 144–146.

- Cunningham, pp. 57–58.

- Cunningham, p. 59.

- Morison, pp. 409-410.

- Cunningham, pp. 59–60.

- Cunningham, pp. 63–64.

- Cunningham, pp. 68–69.

- Cunningham, pp. 61–62.

- Alexander Deconde, A History of American Foreign Policy (1963) p. 127

- Herring, p. 148.

- Cunningham, pp. 65–66.

- Cunningham, p. 67.

- Howe, pp. 104–106.

- Heidler, pp. 501–530.

- Herring, p. 145.

- Johnson, pp. 262–264.

- Cunningham, p. 68.

- Cunningham, pp. 105–107.

- Ammon, pp. 476–492.

- Cunningham, pp. 105–106.

- "The Man Behind the Name". Downtown Lawrenceburg. February 8, 2017. Retrieved February 25, 2017.

- "A Guide to the United States' History of Recognition, Diplomatic, and Consular Relations, by Country, since 1776: Colombia". Office of the Historian, Bureau of Public Affairs United States Department of State. Retrieved February 25, 2017.

- Herring, pp. 140–141.

- Cunningham, pp. 152–153.

- Cunningham, pp. 154–155.

- Cunningham, pp. 156–158.

- Cunningham, pp. 159–160.

- Cunningham, pp. 160–163.

- Howe, pp. 115–116.

- Herring, pp. 151–153, 157.

- "Welcome from the Mississippi Bicentennial Celebration Commission". Mississippi Bicentennial Celebration Commission. Retrieved February 16, 2017.

- "Today in History: December 3". loc.gov. Library of Congress.

- "Alabama History Timeline: 1800-1860". alabama.gov. Retrieved June 15, 2016.

- "Today in History: March 15". loc.gov. Library of Congress.

- "Official Name and Status History of the several States and U.S. Territories". TheGreenPapers.com.

- "Today in History: August 10". loc.gov. Library of Congress.

- "Presidential Elections". history.com. A+E Networks. Retrieved February 7, 2017.

- "James Monroe: Campaigns and Elections". Miller Center of Public Affairs. Retrieved January 8, 2010.

- "Daniel D. Tompkins, 6th Vice President (1817-1825)". United States Senate. Retrieved February 18, 2017.

- Election of 1820

- Parsons 2009, pp. 70–72.

- Howe, pp. 203–204.

- Parsons 2009, pp. 79–86.

- Howe, p. 206.

- Kaplan 2014, pp. 386–389.

- Kaplan 2014, pp. 391–393, 398.

- Schwarz, Frederic D. (February–March 2000). "1825 One Hundred And Seventy-five Years Ago". American Heritage. Rockville, Maryland: American Heritage Publishing. 51 (1). Retrieved March 27, 2017.

- Harry Ammon, "Munro, James." In John A. Garraty, Encyclopedia of American Biography (1974) pp 770-772.

- Ammon, 1974, p 772

- Preston, Daniel. "JAMES MONROE: IMPACT AND LEGACY". Miller Center. Retrieved 4 December 2017.

- Rottinghaus, Brandon; Vaughn, Justin S. (February 19, 2018). "How Does Trump Stack Up Against the Best — and Worst — Presidents?". New York Times. Retrieved 14 May 2018.

- "Presidential Historians Survey 2017". C-Span. Retrieved 14 May 2018.

Works cited

- Abraham, Henry Julian (2008). Justices, Presidents, and Senators: A History of the U.S. Supreme Court Appointments from Washington to Bush II. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 9780742558953.

- Ammon, Harry (2002). Graff, Henry F. (ed.). The Presidents: A Reference History (3rd ed.). Hinsdale, Illinois: Advameg, Inc.

- Cunningham, Noble (1996). The Presidency of James Monroe. University Press of Kansas. ISBN 0-7006-0728-5.

- Dangerfield, George (1965). The Awakening of American Nationalism: 1815–1828. HarperCollins. ISBN 0-88133-823-0.

- Greenstein, Fred I. (June 2009). "The Political Professionalism of James Monroe". Presidential Studies Quarterly. 39 (2): 275–282. doi:10.1111/j.1741-5705.2009.03675.x. JSTOR 41427360.

- Hammond, John Craig. "President, Planter, Politician: James Monroe, the Missouri Crisis, and the Politics of Slavery." Journal of American History 105.4 (2019): 843-867. online.

- Heidler, David S. (1993). "The Politics of National Aggression: Congress and the First Seminole War". Journal of the Early Republic. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. 13 (4): 501–530. JSTOR 3124558.

- Herring, George C. (2008). From Colony to Superpower; U.S. Foreign Relations Since 1776. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-507822-0.

- Howe, Daniel Walker (2007). What Hath God Wrought: The Transformation of America, 1815–1848. Oxford History of the United States. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-507894-2. OCLC 122701433.

- Johnson, Allen (1915). Union and Democracy. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company.

- Kaplan, Fred (2014). John Quincy Adams: American Visionary. HarperCollins.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Morison, Samuel Eliot (1965). The Oxford History of the American People. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Parsons, Lynn H. (1998). John Quincy Adams. Rowman and LittleField.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Unger, Harlow G.. "The Last Founding Father: James Monroe and a Nation's Call to Greatness" (2009)

- Weeks, William Earl (1992). John Quincy Adams and American Global Empire. Lexington, Kentucky: University of Kentucky Press.

- Wilentz, Sean (September 2004). "Jeffersonian Democracy and the Origins of Political Antislavery in the United States: The Missouri Crisis Revisited". Journal of The Historical Society. 4 (3): 375–401. doi:10.1111/j.1529-921X.2004.00105.x.

- Wilentz, Sean (2005). The Rise of American Democracy: Jefferson to Lincoln. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0-393-05820-4.

Further reading

- Ammon, Harry (1958). "James Monroe and the Era of Good Feelings". Virginia Magazine of History and Biography. 66 (4): 387–398. JSTOR 4246479.

- Ammon, Harry (1971). James Monroe: The Quest for National Identity. McGraw-Hill.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bemis, Samuel Flagg (1949). John Quincy Adams and the Foundations of American Foreign Policy. New York: Knopf., the standard history of Monroe's foreign policy.

- Cresson, William P. James Monroe (1946). 577 pp. good scholarly biography

- Dangerfield, George. Era of Good Feelings (1953) excerpt and text search

- Finkelman, Paul, ed. Encyclopedia of the New American Nation, 1754–1829 (2005), 1600 pp.

- Hart, Gary. James Monroe (2005), superficial, short, popular biography

- Haworth, Peter Daniel. "James Madison and James Monroe Historiography: A Tale of Two Divergent Bodies of Scholarship." in A Companion to James Madison and James Monroe (2013): 521-539.

- Leibiger, Stuart, ed. A Companion to James Madison and James Monroe (2012) excerpt; emphasis on historiography

- McManus, Michael J. “President James Monroe’s Domestic Policies, 1817–1825: ‘To Advance the Best Interests of Our Union,’” in A Companion to James Madison and James Monroe, ed. Stuart Leibiger (2013), 438–55.

- Mahon, John K (1998). "The First Seminole War, November 21, 1817-May 24, 1818". Florida Historical Quarterly. 77 (1): 62–67. JSTOR 30149093.

- May, Ernest R. The Making of the Monroe Doctrine (1975), argues it was issued to influence the outcome of the presidential election of 1824.

- Morgan, William G (1972). "The Congressional Nominating Caucus of 1816: The Struggle against the Virginia Dynasty". Virginia Magazine of History and Biography. 80 (4): 461–475. JSTOR 4247750.

- Perkins, Bradford. Castlereagh and Adams: England and the United States, 1812–1823 (1964)

- Perkins, Dexter. The Monroe Doctrine, 1823–1826 (1927), the standard monograph about the origins of the doctrine.

- Renehan Edward J., Jr. The Monroe Doctrine: The Cornerstone of American Foreign Policy (2007)

- Scherr, Arthur. "James Monroe and John Adams: An Unlikely 'Friendship'". The Historian 67#3 (2005) pp 405+. online edition

- Skeen, Carl Edward. 1816: America Rising (1993) popular history

- Styron, Arthur. The Last of the Cocked Hats: James Monroe and the Virginia Dynasty (1945). 480 pp. thorough, scholarly treatment of the man and his times.

- Van Atta, John R. Wolf by the Ears: The Missouri Crisis, 1819–1821 (2015).

- Whitaker, Arthur P. The United States and the Independence of Latin America (1941)

- White, Leonard D. The Jeffersonians: A Study in Administrative History, 1801–1829 (1951), explains the operation and organization of federal administration.

Primary sources

- Preston, Daniel, ed. The Papers of James Monroe: Selected Correspondence and Papers (6 vol, 2006 to 2017), the major scholarly edition; in progress, with coverage to 1814.

- Monroe, James. The Political Writings of James Monroe. ed. by James P. Lucier, (2002). 863 pp.

- Writings of James Monroe, edited by Stanislaus Murray Hamilton, ed., 7 vols. (1898–1903), online edition at Internet Archive The%20Papers%20of%20James%20Monroe%22&f=false online v 6.

- Richardson, James D. ed. A Compilation of the Messages and Papers of the Presidents vol 2 (1897), reprints his official messages and reports to Congress. online vol 2

External links

- James Monroe: A Resource Guide at the Library of Congress

- United States Congress. "Presidency of James Monroe (id: m000858)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.

- A Guide to the Papers of James Monroe 1778–1831 at the University of Virginia Library

- Monroe Doctrine; December 2, 1823 at the Avalon Project

- James Monroe Museum and Memorial Library

- "Life Portrait of James Monroe", from C-SPAN's American Presidents: Life Portraits, April 12, 1999

- Works by James Monroe at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

.jpg)