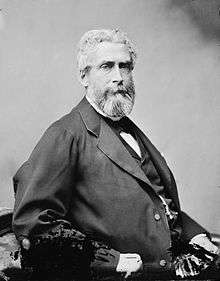

John Lothrop Motley

John Lothrop Motley (April 15, 1814 – May 29, 1877) was an American author, best known for his two popular histories The Rise of the Dutch Republic and The United Netherlands. He was also a diplomat, who helped to prevent European intervention on the side of the Confederates in the American Civil War.

John Lothrop Motley | |

|---|---|

| |

| United States Minister to the United Kingdom | |

| In office June 18, 1869 – December 6, 1870 | |

| President | Ulysses S. Grant |

| Preceded by | Reverdy Johnson |

| Succeeded by | Robert C. Schenck |

| United States Minister to Austria | |

| In office November 14, 1861 – June 14, 1867 | |

| President | Abraham Lincoln Andrew Johnson |

| Preceded by | Jehu Glancy Jones |

| Succeeded by | Henry M. Watts |

| Personal details | |

| Born | John Lothrop Motley April 15, 1814 Dorchester, near Boston, Massachusetts |

| Died | May 29, 1877 (aged 63) Dorchester, Dorset |

| Nationality | American |

| Occupation | Historian and diplomat |

| Part of a series on |

| Dedham, Massachusetts |

|---|

|

| History |

| People |

|

| Places |

| Organizations |

| Businesses |

| Education |

Biography

John Lothrop Motley was born on April 15, 1814 in Dorchester, Massachusetts. His grandfather, Thomas Motley, a jail-keeper (a public position) and innkeeper in Portland, Maine, had been a Freemason and radical sympathizer with the French Revolution. Motley's father Thomas and uncle Edward served mercantile apprenticeships in Portland.[1]

In 1802, Thomas Motley moved to Boston and established a commission house on India Wharf, taking his brother Edward with him as clerk. "Thomas and Edward Motley" became one of the leading commission houses in Boston. Thomas, married Anna Lothrop, daughter of the Rev. John Lathrop, product of an old and distinguished line of Massachusetts clergymen. Like other successful Boston merchants of the period, Thomas Motley devoted a great part of his wealth to civic purposes and the education of his children. The brilliant accomplishments of his second son, J.L. Motley, are evidence of the care both the father and mother—known both for her learning and what Motley's boyhood friend Wendell Phillips called her "regal beauty"—bestowed on the boy's intellectual development. Motley attended the Round Hill School and Boston Latin School, and graduated from Harvard in 1831. His boyhood was spent in Dedham, near the site of the present day Noble and Greenough School.[2] His education included training in the German language and literature, and he went to Germany to complete these studies at Göttingen, during 1832–1833, during which time he became a lifelong friend of Otto von Bismarck. Motley and Bismarck studied civil law together at Frederick William University, Berlin. Bismarck recalled his early impression of Motley: "He exercised a marked attraction by a conversation sparkling with wit, humor or originality....The most striking feature of his handsome and delicate appearance was his uncommonly large and beautiful eyes."[3] After a period of European travel, Motley returned in 1834 to Boston, where he continued his legal studies.[4]

In 1837 he married Mary Benjamin (died 1874). She came from a wealthy Boston family; her brother was Park Benjamin Sr.. In 1839 he published anonymously a novel titled Morton's Hope, or the Memoirs of a Provincial, about life in a German university, based on his own experiences. It was poorly received, but has later been recognized for featuring a valuable portrayal of Bismarck, "thinly disguised as Otto von Rabenmarck", as a young student.[5]

In 1841, Motley entered the U.S. diplomatic service as secretary of legation in St. Petersburg, Russia, but resigned his post within three months, because of the harsh climate, the expenses living there, and his reserved habits. Returning to Boston, he soon entered definitely upon a literary career. Besides contributing various historical and critical essays to the North American Review, such as "Life and Character of Peter the Great" (1845), and a remarkable essay on the "Polity of the Puritans", he published in 1849, again anonymously, a second novel, titled Merry Mount, a Romance of the Massachusetts Colony, based again on the odd history of Thomas Morton and Merrymount. He was elected a member of the American Antiquarian Society in 1856.[6]

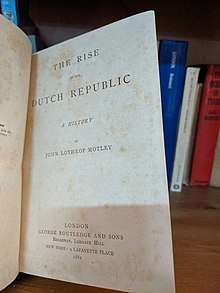

Dutch history

In 1846, Motley had begun to plan a history of the Netherlands, in particular the period of the United Provinces, and he had already done a large amount of work on this subject when, finding the materials at his disposal in the United States inadequate, he went with his wife and children to Europe in 1851. The next five years were spent at Dresden, Brussels, and The Hague in investigation of the archives, which resulted in 1856 in the publication of The Rise of the Dutch Republic, which became very popular. It speedily passed through many editions and was translated into Dutch, French, German, and Russian. In 1860, Motley published the first two volumes of its continuation, The United Netherlands. This work was on a larger scale and embodied the results of a still greater amount of original research. It was brought down to the truce of 1609 by two additional volumes, published in 1867.[7]

Reception in Britain and the United States

The books were popular and critical successes in both Britain and the United States, and multiple editions over the decades sold tens of thousands of copies. It was a favorite prize that schools awarded to their best students. Owen Edwards says of Motley, "He and he alone had created a Dutch awareness on a wide scale."[8]

American critics have given the book mixed reviews. It was quite popular in its day, but modern scholars argue:

- Motley’s overdramatization and didacticism, combined with research less intense than Prescott's or Parkman’s, have cost his works in staying power. Scholars have largely rewritten the story of the Dutch Republic; it is the rare modern who would, for pleasure alone, read Motley from cover to cover, even his Rise of the Dutch Republic. But particular characterizations and episodes in his writings--notably the portraits of William of Orange and Philip II and the descriptions of the Siege of Leyden, the abdication of Charles V, and the assassination of William-- are not excelled in American literature for glint and lift and thud of language.[9]

Reception in the Netherlands

The reception of Motley's work in the Netherlands itself was not wholly favorable, especially as Motley described the Dutch struggle for independence in a flattering light, which caused some to argue he was biased against their opponents. Although historians like the orthodox Protestant Guillaume Groen van Prinsterer (whom Motley extensively quotes in his work) viewed him very favorably, the eminent liberal Dutch historian Robert Fruin (who was inspired by Motley to do some of his own best work, and who had reported already in 1856 in the Westminster Review Motley's edition on the Rise of the Dutch Republic) was critical of Motley's tendency to make up "facts" if they made for a good story. Though he admired Motley's gifts as an author, and stated that he continued to hold the work as a whole in high regard, he stressed it still required "addition and correction".[10]

The humanist historian Johannes van Vloten was very critical, and responded to Fruin in 1860: "I agree less with your too favorable judgement....We cannot build on Motley['s foundation]; for that — apart from the little he copied from Groen's Archives and Gachard's Correspondences — for that his views are generally too obsolete." Although appreciating his efforts to make Dutch history known among an English-speaking audience, Van Vloten argues that Motley's lack of knowledge of the Dutch language prevented him from sharing the latest insights of the Dutch historiographers, and made him vulnerable to bias in favor of Protestants and against Catholics.[11]

Civil War

In 1861, just after outbreak of the American Civil War, Motley wrote two letters to The Times defending the Federal position, and these letters, afterwards reprinted as a pamphlet entitled Causes of the Civil War in America,[12] made a favourable impression on President Lincoln. At this point the English census of 1861 confirms that he was living with his wife and two daughters at 31 Hertford Street, in the parish of St George's, Hanover Square, London and describing himself as an 'author - history'.[13]

Partly owing to this essay, Motley was appointed United States minister to the Austrian Empire in 1861, a position which he filled with distinction, working with other American diplomats such as John Bigelow and Charles Francis Adams to help prevent European intervention on the side of the Confederacy in the American Civil War. He resigned this position in 1867.[14] Two years later, he was sent to represent his country as Ambassador to the United Kingdom, but in November 1870 he was recalled by President Grant. Motley had angered Grant when he completely disregarded Secretary of State Hamilton Fish's carefully drafted orders regarding settlement of the Alabama Claims.[15] After a short visit to the Netherlands, Motley again went to live in England, where the Life and Death of John Barneveld, Advocate of Holland: with a View of the Primary Causes and Movements of the Thirty Years War appeared in two volumes in 1874.[16]

Ill health now began to interfere with his literary work, and he died at Kingston Russell House, near Dorchester, Dorset, leaving three daughters. He was buried in Kensal Green Cemetery, London.[17]

Selected works

- Morton's Hope, or the Memoirs of a Provincial, 1839

- Life and Character of Peter the Great (North American Review), 1845

- On Balzac's Novels (North American Review), 1847

- Merry Mount, a Romance of the Massachusetts Colony, 1849

- Polity of the Puritans (North American Review), 1849

- The Rise of the Dutch Republic, 3 vol., 1856

- Florentine Mosaics (Atlantic Monthly), 1857

- History of the United Netherlands, 4 vol., 1860–67

- Causes of the Civil War in America (from The Times), 1861

- Historic Progress and American Democracy, 1868

- Review of S. E. Henshaw's History of the Work of the North-West Sanitary Commission (Atlantic Monthly), 1868

- Democracy, the Climax of Political Progress and the Destiny of Advanced Races: an Historical Essay, 1869. (Pamphlet reprint of "Historic Progress and American Democracy," listed above.)

- The Life and Death of John of Barneveld, 2 vol., 1874

References

- "Motley, John Lothrop". Encyclopædia Britannica. (11th ed. 1911). 18:909–910.

- Guide Book To New England Travel. 1919.

- Sommers, 2017.

- Encyclopædia Britannica. (1911). 18:909–910.

- Steinberg (2011), pp. 39–41

- Encyclopædia Britannica. (1911). 18:909–910.

- Encyclopædia Britannica. (1911). 18:909–910.

- Edwards, 1982, p. 173.

- Robert E. Spiller, et al., eds. Literary history of the United States (2nd ed., 1953) p. 535.

- Encyclopædia Britannica. (1911). 18:909–910.

- Encyclopædia Britannica. (1911). 18:909–910.

- Making of America - The Causes of The American Civil War: A letter to the London Times.

- "Ancestry.co.uk".

- "Former U.S. ambassadors to Austria". U.S. Embassy in Vienna. Archived from the original on September 7, 2008. Retrieved 2008-12-31.

- Corning, Amos Elwood (1918). Hamilton Fish. Lamere Publishing Company. pp. 59–84.

Hamilton Fish.

- The Life and Death of John of Barneveld, Advocate of Holland, by John Lothrop Motley (1874)

- John Lothrop Motley's gravestone

Further reading

- Baarssen, G.H. Joost (2014). America's True Mother Country? Images of the Dutch in the Second Half of the Nineteenth Century. London: LIT Verlag. ISBN 3-643-90492-4.

- Edwards, Owen Dudley. "John Lothrop Motley and the Netherlands." BMGN-Low Countries Historical Review 97.3 (1982): 561-588. online

- Guberman, Joseph. The Life of John Lothrop Motley (Springer, 2012).

- Haight, Gordon S. "The Publication of Motley's Rise of the Dutch Republic." The Yale University Library Gazette (1980): 135-140 online.

- Kaplan, Lawrence S. "The Brahmin as Diplomat in Nineteenth Century America: Everett Bancroft Motley Lowell." Civil War History 19.1 (1973): 5-28.

- Putnam, Ruth. "Prescott and Motley," Cambridge History of American Literature (1918), 2:131-47, 501-03. online

- Sommers, William. "John Lothrop Motley: The Witty US Minister to Vienna" Foreign Vistas: Stories from a Life in the Foreign Service. (2017), p. 1+. online

- Steinberg, Jonathan. "The American connection: John Lothrop Motley, George Bancroft and Andrew Dickson White. Eminent Americans and Otto von Bismarck." Realpolitik für Europa (Verlag Ferdinand Schöningh, 2016) pp. 267-280.

- Steinberg, Jonathan (2011). Bismarck: A Life. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-978252-9.

- Wheaton, Robert (1962). "Motley and the Dutch Historians". New England Quarterly. 35 (3): 318–336. doi:10.2307/363823. JSTOR 363823.

![]()

Primary sources

- The Rise of the Dutch Republic, 3 vol., 1856; many editions online

- History of the United Netherlands, 4 vol., 1860–67; many editions online

- Holmes, Sr., Oliver Wendell (1879). John Lothrop Motley: A Memoir.

- Motley, John Lothrop (1939). Higby, Chester Penn; Schantz, B.T. (eds.). John Lothrop Motley: Representative Selections.

- Motley, John Lothrop. The Correspondence of John Lothrop Motley (G.W. Curtis, ed. 3 vol. Harper & brothers, 1889). vol 1 online; also vol 2 online; and vol 3 online

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: John Lothrop Motley |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to John Lothrop Motley. |

- Works by John Lothrop Motley at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about John Lothrop Motley at Internet Archive

| Diplomatic posts | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Anson Burlingame |

U.S. Minister to the Austrian Empire 1861 – 1867 |

Succeeded by Henry M. Watts |

| Preceded by Reverdy Johnson |

U.S. Minister to Great Britain 1869 – 1870 |

Succeeded by Robert C. Schenck |