William Henry Harrison

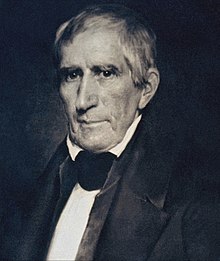

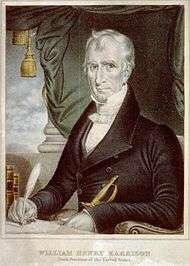

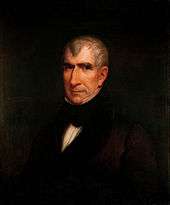

William Henry Harrison (February 9, 1773 – April 4, 1841) was an American military officer and politician who served as the ninth president of the United States in 1841. He died of typhoid, pneumonia or paratyphoid fever 31 days into his term (the shortest tenure), becoming the first president to die in office.[2] His death sparked a brief constitutional crisis regarding succession to the presidency, because the Constitution was unclear as to whether Vice President John Tyler should assume the office of president or merely execute the duties of the vacant office. Tyler claimed a constitutional mandate to become the new president and took the presidential oath of office, setting an important precedent for an orderly transfer of the presidency and its full powers when the previous president fails to complete the elected term.[3]

William Henry Harrison | |

|---|---|

| |

| 9th President of the United States | |

| In office March 4, 1841 – April 4, 1841 | |

| Vice President | John Tyler |

| Preceded by | Martin Van Buren |

| Succeeded by | John Tyler |

| 3rd United States Minister to Gran Colombia | |

| In office May 24, 1828 – September 26, 1829 | |

| President | |

| Preceded by | Beaufort Taylor Watts |

| Succeeded by | Thomas Patrick Moore |

| United States senator from Ohio | |

| In office March 4, 1825 – May 20, 1828 | |

| Preceded by | Ethan Allen Brown |

| Succeeded by | Jacob Burnet |

| Member of Ohio Senate | |

| In office 1819–1821 | |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Ohio's 1st district | |

| In office October 8, 1816 – March 3, 1819 | |

| Preceded by | John McLean |

| Succeeded by | Thomas R. Ross |

| 1st Governor of the Indiana Territory | |

| In office January 10, 1801 – December 28, 1812 | |

| Appointed by | John Adams |

| Preceded by | Office established |

| Succeeded by | Thomas Posey |

| Delegate to the U.S. House of Representatives from the Northwest Territory | |

| In office March 4, 1799 – May 14, 1800 | |

| Preceded by | Constituency established |

| Succeeded by | William McMillan |

| 2nd Secretary of the Northwest Territory | |

| In office June 28, 1798 – October 1, 1799 | |

| Governor | Arthur St. Clair |

| Preceded by | Winthrop Sargent |

| Succeeded by | Charles Willing Byrd |

| Personal details | |

| Born | February 9, 1773 Charles City County, Virginia, British America |

| Died | April 4, 1841 (aged 68) Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Cause of death | Pneumonia[1] |

| Resting place | Harrison Tomb State Memorial |

| Political party |

|

| Spouse(s) | |

| Children | 10, including John and Carter |

| Relatives |

|

| Education | |

| Awards | |

| Signature | |

| Military service | |

| Branch/service |

|

| Years of service | 1791–1798, 1811, 1812–1814 |

| Rank | Major General |

| Unit | Legion of the United States |

| Commands | Army of the Northwest |

| Battles/wars | |

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

Military service

9th President of the United States

Appointments

|

||

Harrison was born in Charles City County, Virginia, a son of Founding Father Benjamin Harrison V and the paternal grandfather of Benjamin Harrison, the 23rd president of the United States. He was the last president born as a British subject in the Thirteen Colonies before the Declaration of Independence in 1776. During his early military career, he participated in the 1794 Battle of Fallen Timbers, an American military victory that effectively ended the Northwest Indian War. Later, he led a military force against Tecumseh's Confederacy at the Battle of Tippecanoe in 1811,[4] where he earned the nickname "Old Tippecanoe". He was promoted to major general in the Army in the War of 1812, and in 1813 led American infantry and cavalry at the Battle of the Thames in Upper Canada.[2][5]

Harrison began his political career in 1798, when he was appointed Secretary of the Northwest Territory, and in 1799 he was elected as the territory's delegate in the House of Representatives. Two years later, President John Adams named him governor of the newly established Indiana Territory, a post he held until 1812. After the War of 1812, he moved to Ohio where he was elected to represent the state's 1st district in the House in 1816. In 1824, the Ohio state legislature elected him to the U.S. Senate; his term was truncated by his appointment as Minister Plenipotentiary to Gran Colombia in May 1828. Afterward, he returned to private life in North Bend, Ohio until he was nominated as the Whig Party candidate for president in the 1836 election; he was defeated by Democratic vice president Martin Van Buren. Four years later, the party nominated him again with John Tyler as his running mate, and the Whig campaign slogan was "Tippecanoe and Tyler Too". They defeated Van Buren in the 1840 United States presidential election, making Harrison the first Whig to win the presidency.

At 68 years, 23 days of age at the time of his inauguration, Harrison was the oldest person to assume the U.S. presidency, a distinction he held until 1981, when Ronald Reagan was inaugurated at age 69 years, 349 days.[6] Due to his brief tenure, scholars and historians often forgo listing him in historical presidential rankings. However, historian William W. Freehling calls him "the most dominant figure in the evolution of the Northwest territories into the Upper Midwest today".[7]

Early life and education

Harrison was the seventh and youngest child of Benjamin Harrison V and Elizabeth (Bassett) Harrison, born on February 9, 1773 at Berkeley Plantation, the Harrison family home along the James River in Charles City County, Virginia. He was a member of a prominent political family of English descent whose ancestors had been in Virginia since the 1630s[8][9] and the last American president not born as an American Citizen. His father was a Virginian planter, who served as a delegate to the Continental Congress (1774–1777) and who signed the Declaration of Independence. His father also served in the Virginia legislature and as the fifth governor of Virginia (1781–1784) in the years during and after the American Revolutionary War.[10][11][12] Harrison's older brother Carter Bassett Harrison represented Virginia in the House of Representatives (1793–1799).[9][13]

Harrison was tutored at home until age 14 when he entered Hampden–Sydney College, a Presbyterian college in Virginia.[14] He studied there for three years, receiving a classical education which included Latin, Greek, French, logic, and debate.[15][16] His Episcopalian father removed him from the college, possibly for religious reasons, and he briefly attended a boys' academy in Southampton County, Virginia before being transferred to Philadelphia in 1790.

He boarded with Robert Morris and entered the University of Pennsylvania in April 1791, where he studied medicine under Doctor Benjamin Rush and William Shippen Sr.[17][18] His father died in the spring of 1791, shortly after he began his medical studies. He was only 18 and Morris became his guardian; he also discovered that his family's financial situation left him without funds for further schooling, so he abandoned medical school in favor of a military career after being persuaded by Governor Henry Lee III, a friend of Harrison's father.[16][19][18]

Early military career

On August 16, 1791, Harrison was commissioned as an ensign in the Army in the 1st Infantry Regiment within 24 hours of meeting Lee. He was 18 years old at the time. He was initially assigned to Fort Washington, Cincinnati in the Northwest Territory where the army was engaged in the ongoing Northwest Indian War.[20][21]

Harrison was promoted to lieutenant after Major General "Mad Anthony" Wayne took command of the western army in 1792 following a disastrous defeat under Arthur St. Clair. In 1793, he became Wayne's aide-de-camp and learned how to command an army on the American frontier; he participated in Wayne's decisive victory at the Battle of Fallen Timbers on August 20, 1794, which ended the Northwest Indian War.[20][22] Harrison was a signatory of the Treaty of Greenville (1795) as witness to Wayne, the principal negotiator for the U.S. Under the terms of the treaty, a coalition of Indians ceded a portion of their lands to the federal government, opening two-thirds of Ohio to settlement.[20][9][23][24]

Following his mother's death in 1793, Harrison inherited a portion of his family's Virginia estate, including approximately 3,000 acres (12 km2) of land and several slaves. He was serving in the Army at the time and sold his land to his brother.[25]

Harrison was promoted to Captain in May 1797 and resigned from the Army on 1 June 1798.[2]

Marriage and family

Harrison met Anna Tuthill Symmes of North Bend, Ohio in 1795 when he was 22. She was a daughter of Anna Tuthill and Judge John Cleves Symmes, who served as a colonel in the Revolutionary War and a representative to the Congress of the Confederation.[9][26] Harrison asked the judge for permission to marry Anna but was refused, so the couple waited until Symmes left on business. They then eloped and were married on November 25, 1795[27] at the North Bend home of Dr. Stephen Wood, treasurer of the Northwest Territory. They honeymooned at Fort Washington, since Harrison was still on military duty. Judge Symmes confronted him two weeks later at a farewell dinner for General Wayne, sternly demanding to know how he intended to support a family. Harrison responded, "by my sword, and my own right arm, sir."[28] Harrison won over his father-in-law, who later sold the Harrisons 160 acres (65 ha) of land in North Bend, which enabled Harrison to build a home and start a farm.[29]

The Harrisons had ten children: Elizabeth Bassett (1796–1846), John Cleves Symmes (1798–1830), Lucy Singleton (1800–1826), William Henry (1802–1838), John Scott (1804–1878) father of future U.S. president Benjamin Harrison, Benjamin (1806–1840), Mary Symmes (1809–1842), Carter Bassett (1811–1839), Anna Tuthill (1813–1865), James Findlay (1814–1817).[30] Anna was frequently in poor health during the marriage, primarily due to her many pregnancies, yet she outlived William by 23 years, dying on February 25, 1864 at 88.[15][31]

Harrison also allegedly had an additional six children by Dilsia, an enslaved African-American woman. Among these was a grandmother of Walter Francis White.[32] The story is unlikely, however, given Harrison's early departure from the south.[33]

Political career

Harrison began his political career when he resigned from the military on June 1, 1798[20][34] and campaigned among his friends and family for a post in the Northwest Territorial government. His close friend Timothy Pickering was serving as Secretary of State, and he helped him to get a recommendation to replace Winthrop Sargent, the outgoing territorial secretary. President John Adams appointed Harrison to the position in July 1798. He also frequently served as acting territorial governor during the absences of Governor Arthur St. Clair.[20][35]

U.S. Congress

Harrison had many friends in the eastern aristocracy and quickly gained a reputation among them as a frontier leader. He ran a successful horse-breeding enterprise that won him acclaim throughout the Northwest Territory. Congress had legislated a territorial policy which led to high land costs, and this became a primary concern for settlers in the Territory; Harrison became their champion to lower those prices. The Northwest Territory's population reached a sufficient number to have a delegate in Congress in October 1799, and Harrison ran for election.[36] He campaigned to encourage further migration to the territory, which eventually led to statehood.[37]

Harrison defeated Arthur St. Clair Jr. by one vote to become the Northwest Territory's first congressional delegate in 1798 at age 26. He served in the Sixth United States Congress from March 4, 1799 to May 14, 1800.[9][40] He had no authority to vote on legislative bills, but he was permitted to serve on a committee, to submit legislation, and to engage in debate.[41] He became chairman of the Committee on Public Lands and promoted the Land Act of 1800, which made it easier to buy land in the Northwest Territory in smaller tracts at a low cost. The sale price for public lands was set at $2 per acre,[42] and this became an important contributor to rapid population growth in the Territory.[43]

Harrison also served on the committee that decided how to divide the Territory into smaller sections, and they recommended splitting it in two. The eastern section continued to be known as the Northwest Territory and consisted of Ohio and eastern Michigan; the western section was named the Indiana Territory and consisted of Indiana, Illinois, Wisconsin, a portion of western Michigan, and the eastern portion of Minnesota.[42][44] The two new territories were formally established in 1800 following the passage of 2 Stat. 58.[45]

On May 13, 1800, President John Adams appointed Harrison as the governor of the Indiana Territory, based on his ties to the west and seemingly neutral political stances. Harrison was caught unaware and was reluctant to accept the position until he received assurances from the Jeffersonians that he would not be removed from office after they gained power in the upcoming elections.[46][47] His governorship was confirmed by the Senate and he resigned from Congress to become the first Indiana territorial governor in 1801.[42][48]

Indiana territorial governor

Harrison began his duties on January 10, 1801 at Vincennes, the capital of the Indiana Territory.[49] [50] Presidents Thomas Jefferson and James Madison were both members of the Democratic-Republican Party, and they reappointed him as governor in 1803, 1806, and 1809.[42] He resigned on December 28, 1812 to resume his military career during the War of 1812.[51]

Harrison was assigned to administer the civilian government of the District of Louisiana in 1804, a part of the Louisiana Territory that included land north of the 33rd parallel. In October, a civilian government went into effect and Harrison served as the Louisiana district's executive leader. He administered the district's affairs for five weeks until the Louisiana Territory was formally established on July 4, 1805, and Brigadier General James Wilkinson assumed the duties of governor.[52][53]

In 1805, Harrison built a plantation-style home near Vincennes that he named Grouseland, alluding to the birds on the property; the 13-room home was one of the first brick structures in the territory, and it served as a center of social and political life in the territory during his tenure as governor.[26][31] The territorial capital was moved to Corydon in 1813, and Harrison built a second home at nearby Harrison Valley.[54] He founded Jefferson University at Vincennes in 1801 which was incorporated as Vincennes University on November 29, 1806.[55]

Harrison had wide-ranging powers in the new territory, including the authority to appoint territorial officials and to divide the territory into smaller political districts and counties. One of his primary responsibilities was to obtain title to Indian lands that would allow future settlement and increase the territory's population, which was a requirement for statehood.[9] He was eager to expand the territory for personal reasons, as well, as his political fortunes were tied to Indiana's eventual statehood.

President Jefferson reappointed Harrison as the Indiana territorial governor on February 8, 1803, and he also granted him the authority to negotiate and conclude treaties with the Indians.[51] Between 1803 and 1809, he supervised 11 treaties with Indian leaders that provided the federal government with more than 60,000,000 acres (240,000 km2), including the southern third of Indiana and most of Illinois. The 1804 Treaty of St. Louis with Quashquame required the Sauk and Meskwaki tribes to cede much of western Illinois and parts of Missouri to the federal government. Many of the Sauk greatly resented this treaty and the loss of lands, especially Black Hawk, and this was a primary reason that they sided with the British during the War of 1812. Harrison thought that the Treaty of Grouseland (1805) appeased some of the Indians, but tensions remained high along the frontier. The Treaty of Fort Wayne (1809) raised new tensions when Harrison purchased more than 2.5 million acres (10,000 km²) inhabited by the Shawnee, Kickapoo, Wea, and Piankeshaw tribes; he purchased the land from the Miami tribe, who claimed ownership. He rushed the treaty process by offering large subsidies to the tribes and their leaders so that it would be in force before Jefferson left office and the administration changed.[54][56]

Harrison's pro-slavery position made him unpopular with the Indiana Territory's antislavery advocates, as he made several attempts to introduce slavery into the territory. He was unsuccessful due to the territory's growing anti-slavery movement. In 1803, he lobbied Congress to suspend Article VI of the Northwest Ordinance for 10 years, a move that would allow slavery in the Indiana Territory. At the end of the suspension period, citizens in the territories covered under the ordinance could decide for themselves whether to permit slavery. Harrison claimed that the suspension was necessary to encourage settlement and would make the territory economically viable, but Congress rejected the idea.[57] In 1803 and 1805, Harrison and the appointed territorial judges enacted laws that authorized indentured servitude and gave masters authority to determine the length of service.[58][59]

The Illinois Territory held elections to the legislature's upper and lower houses for the first time in 1809. Lower house members were elected previously, but the territorial governor appointed members to the upper house. Harrison found himself at odds with the legislature after the anti-slavery faction came to power, and the eastern portion of the Indiana Territory grew to include a large anti-slavery population.[60] The Territory's general assembly convened in 1810, and its anti-slavery faction immediately repealed the indenturing laws enacted in 1803 and in 1805.[53][61] After 1809, Harrison's political authority declined as the Indiana territorial legislature assumed more authority and the territory advanced toward statehood. By 1812, he had moved away and resumed his military career.[62]

Jefferson was the primary author of the Northwest Ordinance, and he had made a secret compact with James Lemen to defeat the pro-slavery movement led by Harrison, even though he was a slaveholder himself. Jefferson did not want slavery to expand into the Northwest Territory, as he believed that the institution should end. He donated money to Lemen to found churches in Illinois and Indiana to stop the pro-slavery movement. In Indiana, the founding of an anti-slavery church led to citizens signing a petition and organizing politically to defeat Harrison's efforts to legalize slavery in the territory. Jefferson and Lemen were instrumental in defeating Harrison's attempts in 1805 and 1807 to expand slavery in the territory.[63]

Army general

Tecumseh and Tippecanoe

An Indian resistance movement had been growing against American expansion through the leadership of Shawnee brothers Tecumseh and Tenskwatawa (The Prophet) in a conflict that became known as Tecumseh's War. Tenskwatawa convinced the tribes that they would be protected by the Great Spirit and no harm could befall them if they would rise up against the settlers. He encouraged resistance by telling the tribes to pay white traders only half of what they owed and to give up all the white man's ways, including their clothing, muskets, and especially whiskey.[64]

In August 1810, Tecumseh led 400 warriors down the Wabash River to meet with Harrison in Vincennes. They were dressed in war paint, and their sudden appearance at first frightened the soldiers at Vincennes. The leaders of the group were escorted to Grouseland, where they met Harrison. Tecumseh insisted that the Fort Wayne Treaty was illegitimate, arguing that one tribe could not sell land without the approval of the other tribes; he asked Harrison to nullify it and warned that Americans should not attempt to settle the lands sold in the treaty. Tecumseh informed Harrison that he had threatened to kill the chiefs who signed the treaty if they carried out its terms and that his confederation of tribes was growing rapidly.[65] Harrison said that the Miamis were the owners of the land and could sell it if they so chose. He rejected Tecumseh's claim that all the Indians formed one nation. He said that each tribe could have separate relations with the United States if they chose to. Harrison argued that the Great Spirit would have made all the tribes speak one language if they were to be one nation.[66]

Tecumseh launched an "impassioned rebuttal", in the words of one historian, but Harrison was unable to understand his language.[66] A Shawnee friendly to Harrison cocked his pistol from the sidelines to alert Harrison that Tecumseh's speech was leading to trouble, and some witnesses reported that Tecumseh was encouraging the warriors to kill Harrison. Many of them began to pull their weapons, representing a substantial threat to Harrison and the town, which held a population of only 1,000. Harrison drew his sword, and Tecumseh's warriors backed down when the officers presented their firearms in his defense.[66] Chief Winamac was friendly to Harrison, and he countered Tecumseh's arguments and told the warriors that they should return home in peace since they had come in peace. Before leaving, Tecumseh informed Harrison that he would seek an alliance with the British if the treaty was not nullified.[67] After the meeting, Tecumseh journeyed to meet with many of the tribes in the region, hoping to create a confederation to battle the United States.[68]

Tecumseh was traveling in 1811 when Harrison was authorized by Secretary of War William Eustis to march against the confederation as a show of force. He led an army north with more than 1,000 men to intimidate the Shawnee into making peace, but the tribes launched a surprise attack early on November 7 in the Battle of Tippecanoe. Harrison defeated the tribal forces at Prophetstown next to the Wabash and Tippecanoe Rivers, and he was hailed as a national hero and the battle became famous. However, his troops had greatly outnumbered the attackers, and suffered many more casualties during the battle.[69]

When reporting to Secretary Eustis, Harrison informed him that the battle occurred near the Tippecanoe River and that he feared an imminent reprisal attack. The first dispatch did not make clear which side had won the conflict, and the secretary at first interpreted it as a defeat; the follow-up dispatch clarified the situation. When no second attack came, the Shawnee defeat was more certain. Eustis demanded to know why Harrison had not taken adequate precautions in fortifying his camp against attacks, and Harrison said that he had considered the position strong enough. The dispute was the catalyst of a disagreement between Harrison and the Department of War which continued into the War of 1812.[70]

The press did not cover the battle at first, and one Ohio paper misinterpreted Harrison's first dispatch to mean that he was defeated.[71] By December, however, most major American papers carried stories on the battle, and public outrage grew over the Shawnee. Americans blamed the British for inciting the tribes to violence and supplying them with firearms, and Congress passed resolutions condemning the British for interfering in American domestic affairs. Congress declared war on June 18, 1812,[72] and Harrison left Vincennes to seek a military appointment.[73]

War of 1812

The outbreak of war with the British in 1812 led to continued conflict with Indians in the Northwest. Harrison briefly served as a major general in the Kentucky militia until the government commissioned him on September 17 to command the Army of the Northwest. He received federal military pay for his service, and he also collected a territorial governor's salary from September until December 28, when he formally resigned as governor and continued his military service.[73]

The Americans suffered a defeat in the Siege of Detroit. General James Winchester offered Harrison the rank of brigadier general, but Harrison also wanted sole command of the army. President James Madison removed Winchester from command in September, and Harrison became commander of the fresh recruits. The British and their Indian allies greatly outnumbered Harrison's troops, so Harrison constructed a defensive position during the winter along the Maumee River in northwest Ohio. He named it Fort Meigs in honor of Ohio governor Return J. Meigs Jr.. He received reinforcements in 1813, then took the offensive and led the army north to battle. He won victories in the Indiana Territory and in Ohio and recaptured Detroit, before invading Upper Canada (Ontario). His army defeated the British on October 5, 1813 at the Battle of the Thames, in which Tecumseh was killed.[73][74] This pivotal battle is considered to be one of the great American victories in the war, second only to the Battle of New Orleans.[74][75]

In 1814, Secretary of War John Armstrong divided the command of the army, assigning Harrison to a "backwater" post and giving control of the front to one of Harrison's subordinates.[2] Armstrong and Harrison had disagreed over the lack of coordination and effectiveness in the invasion of Canada, and Harrison resigned from the army in May.[76][77] After the war ended, Congress investigated Harrison's resignation and determined that Armstrong had mistreated him during his military campaign and that his resignation was justified. Congress awarded Harrison a gold medal for his services during the War of 1812.[78]

Harrison and Michigan Territory's Governor Lewis Cass were responsible for negotiating the peace treaty with the Indians.[79] President Madison appointed Harrison in June 1815 to help in negotiating a second treaty with the Indians that became known as the Treaty of Springwells, in which the tribes ceded a large tract of land in the west, providing additional land for American purchase and settlement.[40][80]

Postwar life

Ohio politician

John Gibson replaced Harrison as Indiana territorial governor in 1812, and Harrison resigned from the army in 1814 and returned to his family in North Bend. He cultivated his land and enlarged the log cabin farmhouse, but he soon returned to public life.[81][82] He was elected in 1816 to complete John McLean's term in the House of Representatives, where he represented Ohio's 1st congressional district from October 8, 1816 to March 3, 1819. He declined to serve as Secretary of War under President Monroe in 1817. He was elected to the Ohio State Senate in 1819 and served until 1821, having lost the election for Ohio governor in 1820.[83] He ran for a seat in the House but in 1822 lost by 500 votes to James W. Gazlay. He was elected to the U.S. Senate in 1824, where he served until May 20, 1828. Fellow westerners in Congress called him a "Buckeye", a term of affection related to the native Ohio buckeye tree.[40] He was an Ohio presidential elector in 1820 for James Monroe[84] and for Henry Clay in 1824.[85]

Harrison was appointed in 1828 as minister plenipotentiary to Gran Colombia, so he resigned from Congress and served in his new post until March 8, 1829. He arrived in Bogotá on December 22, 1828 and found the condition of Colombia saddening. He reported to the Secretary of State that the country was on the edge of anarchy, including his opinion that Simón Bolívar was about to become a military dictator. He wrote a rebuke to Bolívar, stating that "the strongest of all governments is that which is most free" and calling on Bolívar to encourage the development of democracy. In response, Bolívar wrote that the United States "seem destined by Providence to plague America with torments in the name of freedom", a sentiment that achieved fame in Latin America.[86] Andrew Jackson took office in March 1829, and he recalled Harrison in order to make his own appointment to the position.[87]

Private citizen

Harrison returned to the United States from Colombia and settled on his farm in North Bend, Ohio, living in relative retirement after nearly four decades of government service. He had accumulated no substantial wealth during his lifetime, and he subsisted on his savings, a small pension, and the income produced by his farm. He cultivated corn and established a distillery to produce whiskey, but he became disturbed by the effects of alcohol on its consumers and closed the distillery. In an address to the Hamilton County Agricultural Board in 1831, he said that he had sinned in making whiskey and hoped that others would learn from his mistake and stop the production of liquors.[88]

In these early years, Harrison also earned money from his contributions to James Hall's A Memoir of the Public Services of William Henry Harrison, published in 1836. That year, he made an unsuccessful run for the presidency as a Whig candidate. Between 1836 and 1840, he served as Clerk of Courts for Hamilton County. This was his job when he was elected president in 1840.[89] About this time, he met abolitionist and Underground Railroad conductor George DeBaptiste who lived in nearby Madison. The two became friends, and DeBaptiste became his personal servant, staying with him until his death.[90] Harrison campaigned for president a second time in 1840; more than a dozen books had been published on his life by then, and he was hailed by many as a national hero.[91]

1836 presidential campaign

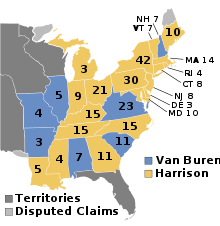

Harrison was the Northern Whig candidate for president in 1836, one of only two times in American history when a major political party intentionally ran more than one presidential candidate (the Democrats ran two candidates in 1860). Vice President Martin Van Buren was the Democratic candidate, and he was popular and deemed likely to win the election against a single Whig candidate. The Whig plan was to elect popular Whigs regionally, deny Van Buren the 148 electoral votes needed for election, and force the House of Representatives to decide the election. They hoped that the Whigs would control the House after the general elections. This strategy would have failed, nonetheless, as the Democrats retained a majority in the House following the election.[92][93]

Harrison ran in all the non-slave states except Massachusetts, and in the slave states of Delaware, Maryland, and Kentucky. Hugh L. White ran in the remaining slave states except for South Carolina. Daniel Webster ran in Massachusetts, and Willie P. Mangum in South Carolina.[94] The plan narrowly failed, as Van Buren won the election with 170 electoral votes. A swing of just over 4,000 votes in Pennsylvania would have given that state's 30 electoral votes to Harrison and the election would have been decided in the House of Representatives.[92][93][95]

1840 presidential campaign

Harrison was the Whig candidate and faced incumbent Van Buren in the 1840 election. He was chosen over more controversial members of the party, such as Clay and Webster, and based his campaign on his military record and on the weak U.S. economy caused by the Panic of 1837.

The Whigs nicknamed Van Buren "Van Ruin" in order to blame him for the economic problems.[96] The Democrats, in turn, ridiculed Harrison by calling him "Granny Harrison, the petticoat general" because he resigned from the army before the War of 1812 ended. They would ask voters what Harrison's name would be when spelled backwards: "No Sirrah". They also cast him as a provincial, out-of-touch old man who would rather "sit in his log cabin drinking hard cider" than attend to the administration of the country. This strategy backfired when Harrison and running mate John Tyler adopted the log cabin and hard cider as campaign symbols. Their campaign used the symbols on banners and posters and created bottles of hard cider shaped like log cabins, all to connect the candidates to the "common man".[97]

Harrison came from a wealthy, slaveholding Virginia family, yet his campaign promoted him as a humble frontiersman in the style popularized by Andrew Jackson, while presenting Van Buren as a wealthy elitist. A memorable example was the Gold Spoon Oration that Pennsylvania's Whig representative Charles Ogle delivered in the House, ridiculing Van Buren's elegant White House lifestyle and lavish spending.[97][98][99] The Whigs invented a chant in which people would spit tobacco juice as they chanted "wirt-wirt," and this also exhibited the difference between candidates from the time of the election:[100]

Old Tip he wore a homespun coat, he had no ruffled shirt: wirt-wirt,

But Matt he has the golden plate, and he's a little squirt: wirt-wirt!

The Whigs boasted of Harrison's military record and his reputation as the hero of the Battle of Tippecanoe. The campaign slogan "Tippecanoe and Tyler, Too" became one of the most famous in American politics.[100] Harrison won a landslide victory in the Electoral College, 234 electoral votes to Van Buren's 60, although the popular vote was much closer. He received 53 percent of the popular vote to Van Buren's 47 percent, with a margin of less than 150,000 votes.[100][101]

Presidency (1841)

_-_Portrait_of_William_Henry_Harrison.jpg) | |

| Presidency of William Henry Harrison | |

|---|---|

| March 4, 1841 – April 4, 1841 | |

| Cabinet | See list |

| Election | 1840 |

| Seat | White House |

| |

| Seal of the President (1840–1850) | |

Shortest presidency

Harrison's wife Anna was too ill to travel when he left Ohio for his inauguration, and she decided not to accompany him to Washington. He asked his late son's widow Jane to accompany him and act as hostess until Anna's proposed arrival in May.

When Harrison came to Washington, he wanted to show that he was still the steadfast hero of Tippecanoe and that he was a better educated and more thoughtful man than the backwoods caricature portrayed in the campaign. He took the oath of office on Thursday, March 4, 1841, a cold and wet day.[102] He braved the cold weather and chose not to wear an overcoat or a hat, rode on horseback to the ceremony rather than in the closed carriage that had been offered him, and delivered the longest inaugural address in American history[102] at 8,445 words. It took him nearly two hours to read, although his friend and fellow Whig Daniel Webster had edited it for length. He became the first head of state to have his photograph taken, then rode through the streets in the inaugural parade[103] and attended three inaugural balls that evening,[104] including one at Carusi's Saloon entitled the "Tippecanoe" ball with 1,000 guests who had paid $10 per person (equal to $297 in 2020).[105]

The inaugural address was a detailed statement of the Whig agenda, essentially a repudiation of Jackson's and Van Buren's policies. Harrison promised to re-establish the Bank of the United States and extend its capacity for credit by issuing paper currency in Henry Clay's American system. He intended to defer to the judgment of Congress on legislative matters, with sparing use of his veto power, and to reverse Jackson's spoils system of executive patronage. He promised to use patronage to create a qualified staff, not to enhance his own standing in government.[106][107]

Clay was a leader of the Whigs and a powerful legislator, as well as a frustrated presidential candidate in his own right, and he expected to have substantial influence in the Harrison administration. He ignored his own platform plank of overturning the "spoils" system and attempted to influence Harrison's actions before and during his brief presidency, especially in putting forth his own preferences for Cabinet offices and other presidential appointments. Harrison rebuffed his aggression: "Mr. Clay, you forget that I am the President."[108] The dispute intensified when Harrison named Daniel Webster as Secretary of State, who was Clay's arch-rival for control of the Whig Party. Harrison also appeared to give Webster's supporters some highly coveted patronage positions. His sole concession to Clay was to name his protégé John J. Crittenden to the post of Attorney General. Despite this, the dispute continued until the president's death.

Clay was not the only one who hoped to benefit from Harrison's election. Hordes of office applicants came to the White House, which (at the time) was open to all who wanted a meeting with the president. Most of Harrison's business during his month-long presidency involved extensive social obligations and receiving visitors at the White House. They awaited him at all hours and filled the Executive Mansion.[103] Harrison wrote in a letter dated March 10, "I am so much harassed by the multitude that calls upon me that I can give no proper attention to any business of my own."[109] Nevertheless, he sent a number of nominations for office to the Senate for confirmation during. The new 27th Congress had convened an extraordinary session for the purpose of confirming his cabinet and other important nominees, since a number of them arrived after Congress' March 15 adjournment; however, Tyler was later forced to renominate many of Harrison's selections.[110]

Harrison took his pledge seriously to reform executive appointments, visiting each of the six executive departments to observe its operations and issuing through Webster an order to all departments that electioneering by employees would be considered grounds for dismissal. He resisted pressure from other Whigs over partisan patronage. A group arrived in his office on March 16 to demand the removal of all Democrats from any appointed office, and Harrison proclaimed, "So help me God, I will resign my office before I can be guilty of such an iniquity!"[111] His own cabinet attempted to countermand his appointment of John Chambers as Governor of Iowa in favor of Webster's friend James Wilson. Webster attempted to press this decision at a March 25 cabinet meeting, and Harrison asked him to read aloud a handwritten note which said simply "William Henry Harrison, President of the United States". He then announced: "William Henry Harrison, President of the United States, tells you, gentlemen, that, by God, John Chambers shall be governor of Iowa!"[112]

Harrison's only official act of consequence was to call Congress into a special session. He and Clay had disagreed over the necessity of such a session, and Harrison's cabinet proved evenly divided so the president vetoed the idea. Clay pressed him on the special session on March 13, but Harrison rebuffed him and told him not to visit the White House again, but to address him only in writing.[114] A few days later, however, Treasury Secretary Thomas Ewing reported to Harrison that federal funds were in such trouble that the government could not continue to operate until Congress' regularly scheduled session in December; Harrison thus relented, and proclaimed the special session on March 17 in the interests of "the condition of the revenue and finance of the country". The session would have begun on May 31 as scheduled if Harrison had lived.[115][116]

Administration and cabinet

| The Harrison Cabinet | ||

|---|---|---|

| Office | Name | Term |

| President | William Henry Harrison | 1841 |

| Vice President | John Tyler | 1841 |

| Secretary of State | Daniel Webster | 1841 |

| Secretary of the Treasury | Thomas Ewing | 1841 |

| Secretary of War | John Bell | 1841 |

| Attorney General | John J. Crittenden | 1841 |

| Postmaster General | Francis Granger | 1841 |

| Secretary of the Navy | George Edmund Badger | 1841 |

Death and funeral

On March 26, 1841, Harrison became ill with cold-like symptoms. His symptoms grew progressively worse over the next two days, at which time a team of doctors was called in to treat him.[117] The prevailing misconception at the time was that his illness had been caused by the bad weather at his inauguration three weeks earlier.[118] The doctors diagnosed him with right lower lobe pneumonia, then placed heated suction cups on his bare torso and administered a series of bloodlettings to draw out the disease.[119] Those procedures failed to bring about improvement, so the doctors treated him with ipecac, castor oil, calomel, and finally with a boiled mixture of crude petroleum and Virginia snakeroot. All this only weakened Harrison further.[117]

Initially, no official announcement was made concerning Harrison's illness, which fueled public speculation and concern the longer he remained out of public view. By the end of the month, large crowds were gathering outside the White House, holding vigil while awaiting any news about the president's condition.[117] Harrison died on April 4, 1841, nine days after becoming ill[120] and exactly one month after taking the oath of office; he was the first president to die in office.[119] Jane McHugh and Philip A. Mackowiak did an analysis in Clinical Infectious Diseases (2014), examining Dr. Miller's notes and records of the White House water supply being downstream of public sewage, and they concluded that he likely died of septic shock due to "enteric fever" (typhoid or paratyphoid fever).[121][122] His last words were to his attending doctor, though assumed to be directed at Vice President John Tyler:

Sir, I wish you to understand the true principles of the government. I wish them carried out. I ask nothing more.[123]

A 30-day period of mourning commenced following the president's death. The White House hosted various public ceremonies, modeled after European royal funeral practices. An invitation only funeral service was also held on April 7 in the East Room of the White House, after which Harrison's coffin was brought to Congressional Cemetery in Washington, D.C. where it was placed in the Public Vault.[124] Solomon Northup gave an account of the procession in Twelve Years a Slave:

The next day there was a great pageant in Washington. The roar of cannon and the tolling of bells filled the air, while many houses were shrouded with crape, and the streets were black with people. As the day advanced, the procession made its appearance, coming slowly through the Avenue, carriage after carriage, in long succession, while thousands upon thousands followed on foot—all moving to the sound of melancholy music. They were bearing the dead body of Harrison to the grave…. I remember distinctly how the window glass would break and rattle to the ground, after each report of the cannon they were firing in the burial ground.[125]

That June, Harrison's body was transported by train and river barge to North Bend, Ohio, and he was buried on July 7 in a family tomb at the summit of Mt. Nebo overlooking the Ohio River which is now the William Henry Harrison Tomb State Memorial.[126]

Impact of death

Harrison's death called attention to an ambiguity in Article II, Section 1, Clause 6 of the Constitution regarding succession to the presidency. The Constitution clearly provided for the vice president to take over the "powers and duties" of the presidency in the event of a president's removal, death, resignation, or inability, but it was unclear whether the vice president formally became president of the United States, or simply temporarily assumed the powers and duties of that office, in a case of succession.[127]

Harrison's cabinet insisted that Tyler was "Vice President acting as President". Tyler was resolute in his claim to the title of President and in his determination to exercise the full powers of the presidency.[128] The cabinet consulted with Chief Justice Roger Taney and decided that, if Tyler took the presidential oath of office, he would assume the office of president. Tyler obliged and was sworn into office on April 6, 1841. Congress convened in May and, after a short period of debate in both houses, passed a resolution which confirmed Tyler as president for the remainder of Harrison's term.[129][130] The precedent that he set in 1841 was followed on seven occasions when an incumbent president died, and it was written into the Constitution in 1967 through Section One of the Twenty-fifth Amendment.[128]

More generally, Harrison's death was a disappointment to Whigs, who hoped to pass a revenue tariff and enact measures to support Henry Clay's American system. Tyler abandoned the Whig agenda, effectively cutting himself off from the party.[131] Three people served as president within a single calendar year: Martin Van Buren, Harrison, and Tyler. This has only happened on one other occasion, when Rutherford B. Hayes, James A. Garfield, and Chester A. Arthur each served in 1881.[132]

Legacy

Historical reputation

Among Harrison's most enduring legacies is the series of treaties that he either negotiated or signed with Indian leaders during his tenure as the Indiana territorial governor.[15] As part of the treaty negotiations, the tribes ceded large tracts of land in the west which provided additional acreage for purchase and settlement.[40][133][80]

Harrison's long-term impact on American politics includes his campaigning methods, which laid the foundation for modern presidential campaign tactics.[134] He was also the first president to have his photograph taken while having incumbency. The image was made in Washington, D.C. on his inauguration day in 1841. Photographs exist of John Quincy Adams, Andrew Jackson, and Martin Van Buren, but these images were taken long after the men's presidential terms had ended. The original daguerreotype of Harrison on his inauguration day has become lost to history, although at least one early photographic copy exists in the archives of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.[135]

Harrison died nearly penniless. Congress voted his wife Anna a presidential widow's pension of $25,000,[136] one year of Harrison's salary (equivalent to about $620,000 in 2019).[137] She also received the right to mail letters free of charge.[138]

Harrison's son John Scott Harrison represented Ohio in the House of Representatives between 1853 and 1857.[139] Harrison's grandson Benjamin Harrison of Indiana served as the 23rd president from 1889 to 1893, making William and Benjamin Harrison the only grandparent-grandchild pair of presidents.[140]

Honors and tributes

On February 19, 2009, the U.S. Mint released the ninth coin in the Presidential $1 Coin Program, bearing Harrison's likeness. A total of 98,420,000 coins were minted.[141][142]

Several monuments and memorial statues have been erected in tribute to Harrison. There are public statues of him in downtown Indianapolis,[143] Cincinnati's Piatt Park,[144] the Tippecanoe County Courthouse,[145] Harrison County, Indiana,[146] and Owen County, Indiana.[147] Numerous counties and towns also bear his name.

To this day the Village of North Bend, Ohio, still honors Harrison every year with a parade sometime around his February 9 birthday.[148]

The Gen. William Henry Harrison Headquarters in Franklinton (now part of Columbus, Ohio) commemorates Harrison. The house was his military headquarters from 1813 to 1814, and is the only remaining building in Ohio associated with him.[149]

2009 Presidential Dollar of William Henry Harrison

2009 Presidential Dollar of William Henry Harrison Equestrian statue of Harrison in Cincinnati, by Louis Rebisso

Equestrian statue of Harrison in Cincinnati, by Louis Rebisso

See also

- Second Party System

- Curse of Tippecanoe

- List of Governors of Indiana

- List of Presidents of the United States

- List of Presidents of the United States by previous experience

- List of Presidents of the United States who died in office

- Presidents of the United States on U.S. postage stamps

References

Citations

- "Harrison dies of pneumonia".

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 13 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 25–26.

- Freehling, William (October 4, 2016). "John Tyler: Domestic Affairs". Charllotesville, Virginia: Miller Center of Public Affairs, University of Virginia. Retrieved March 9, 2019.

- Buescher, John. "Tippecanoe and Walking Canes Too". TeachingHistory.org. Retrieved October 8, 2011.

- Langguth, A. J. (2006). Union 1812: The Americans Who Fought the Second War of Independence, New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-7432-2618-6. p. 206

- Freehling, William (October 4, 2016). "William Henry Harrison: Life In Brief". Charlottesville, Virginia: Miller Center of Public Affairs, University of Virginia. Retrieved March 8, 2019.

- Freehling, William (October 4, 2016). "William Henry Harrison: Impact and Legacy". Charlottesville, Virginia: Miller Center of Public Affairs, University of Virginia. Retrieved March 9, 2019.

- Nelson, Lyle Emerson. American Presidents Year by Year. I. p. 30.

- "William Henry Harrison Biography". About The White House: Presidents. whitehouse.gov. Archived from the original on January 22, 2009. Retrieved June 19, 2008.

- Owens 2007, p. 3.

- Smith, Howard; Riley, Edward M., eds. (1978). Benjamin Harrison and the American Revolution. Virginia in the Revolution. Williamsburg, VA: Virginia Independence Bicentennial Commission. pp. 59–65. OCLC 4781472.

- Barnhart & Riker 1971, p. 315.

- "Carter Bassett Harrison". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. U.S. Congress. Retrieved September 14, 2016.

- Freehling, William (October 4, 2016). "William Henry Harrison: Life Before the Presidency". Charlottesville, Virginia: Miller Center of Public Affairs, University of Virginia. Retrieved March 8, 2019.

- Gugin & St. Clair 2006, p. 18.

- Madison & Sandweiss 2014, p. 45.

- Owens 2007, p. 14.

- Rabin, Alex (January 25, 2017). "With a Penn graduate in the Oval Office for the first time, here's a look at former President William Henry Harrison's time at the University". The Daily Pennsylvanian. Retrieved April 3, 2019.

- Langguth 2007, p. 16.

- Gugin & St. Clair 2006, p. 19.

- Owens 2007, pp. 14, 22.

- Owens 2007, p. 27.

- Langguth 2007, p. 160.

- Owens 2007, pp. 21, 27–29.

- Owens 2007, p. 39.

- Madison & Sandweiss 2014, p. 46.

- Owens 2007, pp. 38–39.

- Dole, Bob; Dole, Robert J. (2001). Great Presidential Wit: -- I Wish I was in this Book. Simon and Schuster. p. 222. ISBN 9780743203920.

- Owens 2007, p. 40.

- "William Henry Harrison: Fast Facts". Charlottesville, Virginia: Miller Center of Public Affairs, University of Virginia. September 26, 2016. Retrieved March 9, 2019.

- Owens 2007, p. 56.

- Kenneth Robert Janken. White: The Biography of Walter White: Mr. NAACP New York: The New York Press, 2003, p.3

- Gail Collins. William Henry Harrison: The American Presidents Series: The 9th President, 1841 Times Books, Henry Holt and Company, 2012, p.103

- "Historical register and dictionary of the United States Army: from its organization, September 29, 1789, to March 2, 1903". archive.org. Washington : Govt. Print. Off. 1903.

- Green 2007, p. 9.

- Gugin & St. Clair 2006, pp. 19–20.

- Owens 2007, pp. 41–45.

- de, Saint-mémin, Charles balthazar julien fevret. "[William Henry Harrison, 9th Pres. of United States, head-and-shoulders portrait, right profile]". Retrieved August 5, 2016.

- "National Park Service – The Presidents (William Henry Harrison)". www.nps.gov. Retrieved August 5, 2016.

- "Harrison, William Henry, (1773–1841)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Retrieved February 4, 2009.

- Owens 2007, pp. 45–46.

- Gugin & St. Clair 2006, p. 20.

- Langguth 2007, p. 161.

- Owens 2007, pp. 49, 50, 54.

- Owens 2007, pp. 47–48.

- Owens 2007, p. 51.

- Barnhart & Riker 1971, p. 314.

- Owens 2007, p. 50–53.

- Owens 2007, p. 53.

- Barnhart & Riker 1971, p. 323.

- Gugin & St. Clair 2006, pp. 20, 23.

- Barnhart & Riker 1971, p. 343.

- Gugin & St. Clair 2006, p. 21.

- Funk 1969, p. 167.

- "History – Vincennes University". www.vinu.edu. Archived from the original on August 16, 2016. Retrieved July 29, 2016.

- Owens 2007, pp. 65–66, 79, 80, 92.

- Owens 2007, pp. 68–69.

- Owens 2007, pp. 69–72.

- Barnhart & Riker 1971, p. 347.

- Barnhart & Riker 1971, p. 355.

- Owens 2007, pp. 179–180.

- Gugin & St. Clair 2006, pp. 22–23.

- Peck, J. M. (June 4, 1851). The Jefferson-Lemen Compact. Retrieved March 28, 2010.

- Langguth 2007, pp. 158–160.

- Langguth 2007, p. 164.

- Langguth 2007, p. 165.

- Langguth 2007, p. 166.

- Langguth 2007, pp. 164–169.

- Langguth 2007, pp. 167–169.

- Owens 2007, pp. 219–220.

- Owens 2007, p. 220.

- Owens 2007, pp. 221, 223.

- Gugin & St. Clair 2006, p. 23.

- Langguth 2007, pp. 268–70.

- Langguth 2007, pp. 291–92.

- Langguth 2007, pp. 291–292.

- Gugin & St. Clair 2006, p. 24.

- "Presidential Series - William H. Harrison". www.nationalguard.mil. Retrieved June 18, 2020.

- Barnhart & Riker 1971, pp. 407–08.

- Barnhart & Riker 1971, pp. 409–10.

- Milligan, Fred (2003). Ohio's Founding Fathers. iUniverse, Inc. pp. 107–108. ISBN 9780595293223.

- Gugin & St. Clair 2006, p. 30.

- https://bioguideretro.congress.gov/Home/MemberDetails?memIndex=h000279

- Taylor & Taylor 1899, p. 102.

- Taylor & Taylor 1899, p. 145.

- Bolívar 1951, p. 732.

- Hall 1836, pp. 301–309.

- Burr 1840, p. 258.

- "Patricia M. Clancy – Clerk of Courts: History of the Clerk of Courts Office". Courtclerk.org. Archived from the original on June 14, 2007. Retrieved December 6, 2011.

- Tobin, Jacqueline L. From Midnight to Dawn: The Last Tracks of the Underground Railroad. Anchor, 2008. pp. 200–209

- Burr 1840, pp. 257–58.

- United States Congress (1837). Senate Journal. 24th Congress, 2nd Session, February 4. pp. 203–204. Retrieved August 20, 2006.

- Shepperd, Michael. "How Close Were The Presidential Elections? 1836". Michigan State University. Retrieved February 11, 2009.

- Lorant, Stefan (1953). The Presidency. New York: The Macmillan Company.

- "Historical Election Results". National Archives. Retrieved June 20, 2008.

- Carnes & Mieczkowski 2001, p. 39.

- Carnes & Mieczkowski 2001, pp. 39–40.

- "The Time Machine: 1840, One Hundred And Fifty Years Ago". American Heritage. April 1990. Archived from the original on February 8, 2006. Retrieved September 21, 2016.

- Bradley, Elizabeth L. (May 27, 2009). Knickerbocker: The Myth behind New York. New Brusnwick, NJ: Rivergate Books. pp. 70–71. ISBN 978-0-8135-4516-5.

- Carnes & Mieczkowski 2001, p. 41.

- Gugin & St. Clair 2006, p. 25.

- "Harrison's Inauguration". American Treasures of the Library of Congress. August 2007. Retrieved September 21, 2009.

- "Harrison's Inauguration (Reason): American Treasures of the Library of Congress". Library of Congress. August 2007. Retrieved June 9, 2008.

- United States Senate (June 10, 2013). "Inaugural Ball". inaugural.senate.gov. Archived from the original on February 25, 2016.

- "Inflation Calculator". Inflation Calculator. Inflation Calculator. Retrieved April 7, 2019.

- "William Henry Harrison Inaugural Address". Inaugural Addresses of the Presidents of the United States. Bartleby.com. 1989. Retrieved February 11, 2009.

- ""I Do Solemnly Swear ...": Presidential Inaugurations". Library of Congress. Retrieved February 11, 2009.

- Borneman 2005, p. 56.

- Letter from Harrison to R. Buchanan, Esq., March 10, 184 1

- http://aprg.web.unc.edu/files/2011/10/Michael-Gerhardt-APRG.pdf

- Woollen, William Wesley (1975). Biographical and historical sketches of early Indiana. Ayer Publishing. p. 51. ISBN 978-0-405-06896-6.

- Remini, Robert (1997). Daniel Webster: The Man and His Time. W.W. Norton & Co. pp. 520–521.

- "Official Portraits of the U.S. Presidents". The White House. Archived from the original on August 15, 2016. Retrieved July 29, 2016.

- "American History Series: The Brief Presidency of William Henry Harrison". Voice of America News. Retrieved June 21, 2009.

- Brinkley, Alan; Dyer, Davis (2004). The American Presidency. Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-618-38273-6. Retrieved June 21, 2009.

- "Harrison's Proclamation for Special Session of Congress" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on July 24, 2011. Retrieved June 21, 2009.

- Jones, Marty (April 6, 2016). "The Thirty-One Day Presidency of William Henry Harrison". historynet.com. Retrieved March 9, 2019.

- Cleaves 1939, p. 152.

- Freehling, William (October 4, 2016). "William Henry Harrison: Death of the President". Charlottesville, Virginia: Miller Center of Public Affairs, University of Virginia. Retrieved March 9, 2019.

- Cleaves 160

- McHugh, Jane; Mackowiak, Philip A. (March 31, 2014). "What Really Killed William Henry Harrison?". The New York Times. Retrieved August 27, 2014.

- McHugh, Jane; Mackowiak, Philip A. (June 23, 2014). "Death in the White House: President William Henry Harrison's Atypical Pneumonia". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 59 (7): 990–995. doi:10.1093/cid/ciu470. PMID 24962997.

- "William Henry Harrison: Key Events". Charlottesville, Virginia: Miller Center of Public Affairs, University of Virginia. October 7, 2016. Retrieved March 9, 2019.

- "William Henry Harrison Funeral: April 7, 1841". whitehousehistory.org. Washington, D.C.: White House Historical Association. Retrieved March 9, 2019.

- Twelve Years a Slave: Narrative of Solomon Northup, a Citizen of New-York, Kidnapped in Washington City in 1841, and Rescued in 1853

- "William Henry Harrison Tomb". ohiohistory.org. Columbus Ohio: Ohio History Connection (formerly the Ohio Historical Society). Retrieved March 9, 2019.

- Feerick, John. "Essays on Article II: Presidential Succession". The Heritage Guide to the Constitution. The Heritage Foundation. Retrieved June 12, 2018.

- "A controversial President who established presidential succession". Constitution Daily. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: National Constitution Center. March 29, 2017. Retrieved March 11, 2019.

- Rankin, Robert S. (February 1946). "Presidential Succession in the United States". The Journal of Politics. 8 (1): 44–56. doi:10.2307/2125607. JSTOR 2125607.

- Abbott, Philip (December 2005). "Accidental Presidents: Death, Assassination, Resignation, and Democratic Succession". Presidential Studies Quarterly. 35 (4): 627–645. doi:10.1111/j.1741-5705.2005.00269.x. JSTOR 27552721.

- "John Tyler, Tenth Vice President (1841)". senate.gov. Retrieved June 18, 2008.

- Kelly, Martin. "Tecumseh's Curse and the US Presidents: Coincidence or Something More?". About.com. Retrieved June 9, 2008.

- Madison & Sandweiss 2014, p. 47.

- Green 2007, p. 100.

- "The Met Collection Database". Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved December 12, 2008.

- Damon, Allan L. (June 1974). "Presidential Expenses". American Heritage. 25 (4). Archived from the original on January 7, 2009. Retrieved February 10, 2009.

- Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved January 1, 2020.

- "First Lady Biography: Anna Harrison". First Ladies. 2009. Retrieved February 11, 2009.

- "Harrison, John Scott, (1804–1878)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Retrieved June 18, 2008.

- Calhoun 2005, pp. 43–49.

- "The United States Mint Coins and Medals Program". www.usmint.gov. Retrieved July 28, 2016.

- "Circulating Coins Production Figures: usmint.gov". www.usmint.gov. Retrieved July 28, 2016.

- Greiff 2005, pp. 12, 164.

- "Statue of William Henry Harrison - Cincinnati, Ohio - American Guide Series on Waymarking.com". www.waymarking.com. Retrieved July 28, 2016.

- Greiff 2005, p. 243.

- Greiff 2005, p. 131.

- Greiff 2005, p. 206.

- Carl Weiser, Jeff Suess, and Sharon Coolidge (February 17, 2020). "In Greater Cincinnati, one of America's most obscure presidents gets a parade". Cincinnati Enquirer.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- "National Register of Historic Places Registration Form". National Park Service. Retrieved May 17, 2020.

Bibliography

- Barnhart, John D.; Riker, Dorothy L., eds. (1971). Indiana to 1816: The Colonial Period. The History of Indiana. I. Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Bureau and the Indiana Historical Society.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bolívar, Simón (1951). Bierck, Harold A. Jr. (ed.). Selected Writings of Bolívar. II. New York: Colonial Press. ISBN 978-1-60635-115-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) compiled by Lecuna, Vicente, translated by Bertrand, Lewis

- Borneman, Walter R. (2005). 1812: The War That Forged a Nation. New York: HarperCollins (Harper Perennial). ISBN 978-0-06-053113-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Burr, Samuel Jones (1840). The Life and Times of William Henry Harrison. New York: R. W.Pomeroy. Retrieved September 14, 2016.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Calhoun, Charles William (2005). Benjamin Harrison: The 23rd President 1889–1893. The American Presidents. 23. New York: Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-8050-6952-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Carnes, Mark C.; Mieczkowski, Yanek (2001). The Routledge Historical Atlas of Presidential Campaigns. Routledge Atlases of American History. New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-92139-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cleaves, Freeman (1939). Old Tippecanoe: William Henry Harrison and His Time. New York: C. Scribner's Sons.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Funk, Arville (1969). A Sketchbook of Indiana History. Rochester, IN: Christian Book Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Green, Meg (2007). William H. Harrison. Breckenridge, CO: Twenty-First Century Books. ISBN 978-0-8225-1511-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link); for children

- Greiff, Glory-June (2005). Remembrance, Faith and Fancy: Outdoor Public Sculpture in Indiana. Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society Press. ISBN 0-87195-180-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gugin, Linda C.; St. Clair, James E., eds. (2006). The Governors of Indiana. Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society Press and the Indiana Historical Bureau. ISBN 0-87195-196-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hall, James (1836). A Memoir of the Public Services of William Henry Harrison, of Ohio. Philadelphia, PA: Key & Biddle. Retrieved September 14, 2016.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Langguth, A. J. (2007). Union 1812: The Americans Who Fought the Second War of Independence. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-1-4165-3278-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Madison, James H.; Sandweiss, Lee Ann (2014). Hoosiers and the American Story. Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society Press. ISBN 978-0-87195-363-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Owens, Robert M. (2007). Mr. Jefferson's Hammer: William Henry Harrison and the Origins of American Indian Policy. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-3842-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Taylor, William Alexander; Taylor, Aubrey Clarence (1899). Ohio statesmen and annals of progress: from the year 1788 to the year 1900 ... 1. State of Ohio.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Booraem, Hendrik (2012). A Child of the Revolution: William Henry Harrison and His World, 1773–1798. Kent State University Press.

- Ellis, Richard J. Old Tip vs. the Sly Fox: The 1840 Election and the Making of a Partisan Nation (U of Kansas Press, 2020) online review

- Graff, Henry F., ed. The Presidents: A Reference History (3rd ed. 2002) online

- Jortner, Adam (2012). The Gods of Prophetstown: The Battle of Tippecanoe and the Holy War for the American Frontier. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-976529-4.

- Peterson, Norma Lois. The Presidencies of William Henry Harrison and John Tyler (U of Kansas Press, 1989).

- Pirtle, Alfred (1900). The Battle of Tippecanoe. Louisville: John P. Morton & Co./ Library Reprints. p. 158. ISBN 978-0-7222-6509-3. as read to the Filson Club.

- Shade, William G. "'Tippecanoe and Tyler too': William Henry Harrison and the rise of popular politics." In Joel H. Silbey, ed., A Companion to the Antebellum Presidents 1837–1861 (2013), pp. 155–72.

- Skaggs, David Curtis. William Henry Harrison and the Conquest of the Ohio Country: Frontier Fighting in the War of 1812 (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2014) xxii.

External links

- White House biography

- United States Congress. "William Henry Harrison (id: H000279)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.

- William Henry Harrison Papers – Library of Congress

- William H. Harrison at Ohio History Central

- Papers of William Henry Harrison, 1800–1815, Collection Guide, Indiana Historical Society

- Announcement of William Henry Harrison Impending Death

- William Henry Harrison ALS, March 10, 1841: Harassed by the Multitudes

- William Henry Harrison's Personal Correspondence While in Office Shapell Manuscript Foundation

- Essays on Harrison, each member of his cabinet and First Lady

- William Henry Harrison Biography and Fact File

- Biography by Appleton's and Stanley L. Klos

- Peckham, Howard Henry (2000). William Henry Harrison: Young Tippecanoe. ISBN 9781882859030.

- "Life Portrait of William Henry Harrison", from C-SPAN's American Presidents: Life Portraits, May 10, 1999

- William Henry Harrison at FindAGrave