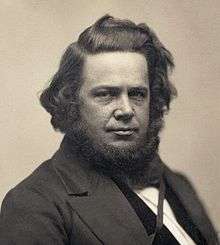

Elias Howe

Elias Howe Jr. (/haʊ/; July 9, 1819 – October 3, 1867) was an American inventor best known for his creation of the modern lockstitch sewing machine.

Elias Howe | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Elias Howe Jr. July 9, 1819 |

| Died | October 3, 1867 (aged 48) Brooklyn, New York |

| Nationality | American |

| Education | apprenticed as mechanic and machinist |

| Occupation | Engineer |

| Spouse(s) | Elizabeth Jennings Ames (m. 1841; d. 1850) Rose Halladay (d. 1890) |

| Children | Jane Robinson Howe, Simon Ames Howe, Julia Maria Howe |

| Parent(s) | Elias Howe and Polly (Bemis) Howe |

| Engineering career | |

| Discipline | Mechanical Engineering |

| Projects | sewing machine |

| Significant advance | lockstitch loop method |

| Awards | Gold Medal, Paris Exposition of 1867, Légion d'honneur (France) |

Early life and family

Elias Howe Jr. was born on July 9, 1819, to Dr. Elias Howe Sr. and Polly (Bemis) Howe in Spencer, Massachusetts. Howe spent his childhood and early adult years in Massachusetts, where he apprenticed in a textile factory in Lowell beginning in 1835. After mill closings due to the Panic of 1837, he moved to Cambridge, Massachusetts, to work as a mechanic with carding machinery, apprenticing along with his cousin Nathaniel P. Banks. Beginning in 1838, he apprenticed in the shop of Ari Davis, a master mechanic in Cambridge who specialized in the manufacture and repair of chronometers and other precision instruments.[1] It was in the employ of Davis that Howe seized upon the idea of the sewing machine.

He married Elizabeth Jennings Ames, daughter of Simon Ames and Jane B. Ames, on March 3, 1841, in Cambridge.[2] They had three children: Jane Robinson Howe (1842–1912), Simon Ames Howe (1844–1883), and Julia Maria Howe (1846–1869).

Invention of sewing machine and career

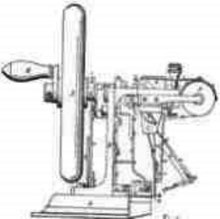

Howe was not the first to conceive of the idea of a sewing machine. Many other people had formulated the idea of such a machine before him, one as early as 1790, and some had even patented their designs and produced working machines, in one case at least 80 of them.[3] However, Howe originated significant refinements to the design concepts of his predecessors, and on September 10, 1846, he was awarded the first United States patent (U.S. Patent 4,750) for a sewing machine using a lockstitch design. His machine contained the three essential features common to most modern machines: a needle with the eye at the point, a shuttle operating beneath the cloth to form the lock stitch, and an automatic feed.

A possibly apocryphal account of how he came up with the idea for placing the eye of the needle at the point is recorded in a family history of his mother's family: "He almost beggared himself before he discovered where the eye of the needle of the sewing machine should be located. It is probable that there are very few people who know how it came about. His original idea was to follow the model of the ordinary needle, and have the eye at the heel. It never occurred to him that it should be placed near the point, and he might have failed altogether if he had not dreamed he was building a sewing machine for a savage king in a strange country. Just as in his actual working experience, he was perplexed about the needle's eye. He thought the king gave him twenty-four hours in which to complete the machine and make it sew. If not finished in that time death was to be the punishment. Howe worked and worked, and puzzled, and finally gave it up. Then he thought he was taken out to be executed. He noticed that the warriors carried spears that were pierced near the head. Instantly came the solution of the difficulty, and while the inventor was begging for time, he awoke. It was 4 o'clock in the morning. He jumped out of bed, ran to his workshop, and by 9, a needle with an eye at the point had been rudely modeled. After that it was easy. That is the true story of an important incident in the invention of the sewing machine."[4]

Despite securing his patent, Howe had considerable difficulty finding investors in the United States to finance production of his invention, so his elder brother Amasa Bemis Howe traveled to England in October 1846 to seek financing. Amasa was able to sell his first machine for £250 to William Thomas of Cheapside, London, who owned a factory for the manufacture of corsets, umbrellas and valises. Elias and his family joined Amasa in London in 1848, but after business disputes with Thomas and failing health of his wife, Howe returned nearly penniless to the United States. His wife Elizabeth, who preceded Elias back to the United States, died in Cambridge, Massachusetts shortly after his return in 1849.[5]

Despite his efforts to sell his machine, other entrepreneurs began manufacturing sewing machines. Howe was forced to defend his patent in a court case that lasted from 1849 to 1854 because he found that Isaac Singer with cooperation from Walter Hunt had perfected a facsimile of his machine and was selling it with the same lockstitch that Howe had invented and patented. He won the dispute and earned considerable royalties from Singer and others for sales of his invention.

Howe contributed much of the money he earned to providing equipment for the 17th Connecticut Volunteer Infantry of the Union Army during the Civil War, in which Howe served as a private in Company D. Due to his faltering health he performed light duty, often seen walking with the aid of his shillelagh, and took on the position of Regimental Postmaster, serving out his time riding to and from Baltimore with war news. He'd enlisted August 14, 1862, and then mustered out July 19, 1865.[6][7]

Involvement in inventing the zipper

Howe received a patent in 1851 for an "Automatic, Continuous Clothing Closure". Perhaps because of the success of his sewing machine, he did not try to seriously market it, missing recognition he might otherwise have received.[8]

Later life and legacy

Between 1865 and 1867, Elias established The Howe Machine Co. in Bridgeport, Connecticut, that was operated by Elias's sons-in-law, the Stockwell Brothers, until about 1886. Between 1854 and 1871/2, Elias's older brother, Amasa Bemis Howe, and later his son Benjamin Porter Howe, as Amasa died in 1868, owned and operated a factory in New York City, manufacturing sewing machines under the name of the Howe Sewing Machine Co., which won a gold medal at the London Exhibition of 1862. Then in 1873, B. P. Howe sold the Howe Sewing Machine Co. factory and name to the Howe Machine Co. which merged the two companies. Elias's sewing machine won a gold medal at the Paris Exhibition of 1867,[1] and that same year he was awarded the Légion d'honneur by Napoleon III for his invention.[9]

Howe died at age 48, on October 3, 1867, of gout and a massive blood clot. He was buried in Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn, New York. His second wife, Rose Halladay, who died on October 10, 1890, is buried with him. Both Singer and Howe were multi-millionaires.[10]

Howe was commemorated with a 5-cent stamp in the Famous American Inventors series issued October 14, 1940.[11] The 1965 Beatles movie Help! is dedicated to his memory.[12] In 2004 he was inducted into the United States National Inventors Hall of Fame.[1]

Genealogy

Howe was a descendant of John Howe (1602–1680) who arrived in Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1630 from Brinklow, Warwickshire, England, and settled in Sudbury, Massachusetts. Howe was also a descendant of Edmund Rice, another early immigrant to Massachusetts Bay Colony.[2][13]

References

- "Elias Howe". National Inventors Hall of Fame. Retrieved July 7, 2020.

- Edmund Rice (1638) Association, 2009. Descendants of Edmund Rice: The First Nine Generations. (CD-ROM)

- "A Brief History of the Sewing Machine". ISMACS International. Retrieved May 22, 2010.

- Waln-Morgan Draper, Thomas, The Bemis History and Genealogy: Being an Account, in Greater Part, of the Descendants of Joseph Bemis of Watertown, Massachusetts, The Bemis History and Genealogy (Washington [District of Columbia]: Library of Congress, [19--]), pp 159–162, 1357 Joshua Bemis, FHL Microfilm 1011936 Item 2.

- "Elias Howe Obituary". New York Times, October 5, 1867. October 5, 1867. Retrieved November 8, 2009.

- "Muster roll, Company D, 17th Connecticut Volunteer Infantry Regiment". Seventeenth Connecticut Volunteer Infantry homepage. Archived from the original on July 20, 2008. Retrieved November 9, 2009.

- Pro Patria: Civil War monument of Connecticut Archived October 16, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- "Zipper History". AnsunMultitech. Archived from the original on July 8, 2012. Retrieved June 22, 2012.

- "French Legion of Honor Recipients". NNDB-Biographic Data Base. Retrieved November 9, 2009.

- Elias Howe, 19th Century Scientific American Online Archived March 20, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- "5-cent Howe", Arago: people, postage & the post, Smithsonian National Postal Museum, viewed September 28, 2014.

- https://www.newenglandhistoricalsociety.com/elias-howe-sewing-machine-inventor-gets-little-help-beatles/

- "Who was Edmund Rice?". The Edmund Rice (1638) Association, Inc. Retrieved November 8, 2009.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Elias Howe. |

- Elias Howe at Find a Grave

- Iles, George (1912), Leading American Inventors, New York: Henry Holt and Company, pp. 338–369

- Elias Howe Biography by Alex I. Askaroff

- . Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography. 1892.

- . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.