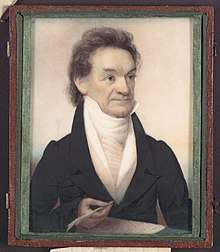

Edward Livingston

Edward Livingston (May 28, 1764 – May 23, 1836) was an American jurist and statesman. He was an influential figure in the drafting of the Louisiana Civil Code of 1825, a civil code based largely on the Napoleonic Code.[1] Livingston represented both New York and then Louisiana in Congress and served as the U.S. Secretary of State from 1831 to 1833.[2]

Edward Livingston | |

|---|---|

| |

| United States Minister to France | |

| In office September 30, 1833 – April 29, 1835 | |

| President | Andrew Jackson |

| Preceded by | Levett Harris (Acting) |

| Succeeded by | Lewis Cass |

| 11th United States Secretary of State | |

| In office May 24, 1831 – May 29, 1833 | |

| President | Andrew Jackson |

| Preceded by | Martin Van Buren |

| Succeeded by | Louis McLane |

| United States senator from Louisiana | |

| In office March 4, 1829 – May 24, 1831 | |

| Preceded by | Charles Dominique Joseph Bouligny |

| Succeeded by | George A. Waggaman |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Louisiana's 1st district | |

| In office March 4, 1823 – March 3, 1829 | |

| Preceded by | Josiah S. Johnston (At-large) |

| Succeeded by | Edward Douglass White Sr. |

| 46th Mayor of New York City | |

| In office 1801–1803 | |

| Preceded by | Richard Varick |

| Succeeded by | DeWitt Clinton |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from New York's 2nd district | |

| In office March 4, 1795 – March 3, 1801 | |

| Preceded by | John Watts |

| Succeeded by | Samuel L. Mitchill |

| Personal details | |

| Born | May 28, 1764 Clermont, New York, British America |

| Died | May 23, 1836 (aged 71) Rhinebeck, New York, U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic-Republican (Before 1825) Jacksonian (1825–1836) |

| Spouse(s) | Mary McEvers

( m. 1788; died 1801)Louise d'Avezac de Castera

( m. 1805; |

| Relations | See Livingston family |

| Education | Princeton University (BA) |

| Signature | |

Early life

Edward Livingston was born in Clermont, Columbia County, New York. He was the youngest son of Judge Robert Livingston and Margaret (née Beekman) Livingston, and was a member of the prestigious Livingston family. His father was a member of the New York Provincial Assembly and a Judge of the New York Supreme Court of Judicature and his mother was heir to immense tracts of land in Dutchess and Ulster counties. Among his many siblings were Chancellor of New York Robert R. Livingston;[3] Janet Livingston, who married Gen. Richard Montgomery;[4] Margaret Livingston, who married New York Secretary of State Thomas Tillotson;[5] Henry Beekman Livingston;[5] Catharine Livingston, who married Freeborn Garrettson;[5][6] merchant John R. Livingston;[7][8][9] Gertrude Livingston, who married Gov. Morgan Lewis; Joanna Livingston, who married Peter R. Livingston, acting Lieutenant Governor of New York; and Alida Livingston, who married John Armstrong, Jr., a U.S. Senator, U.S. Secretary of War, and U.S. Minister to France who was the son of Gen. John Armstrong, Sr.

His maternal grandparents were Henry Beekman, a descendant of Wilhelmus Beekman, and Janet (née Livingston) Beekman, a Livingston cousin. Their children included:[10] His father was the only child of Robert Livingston, known as "Robert of Clermont" (himself a son of Robert Livingston the Elder, the first Lord of Livingston Manor, and Alida (née Schuyler) Van Rensselaer Livingston) and Margaret (née Howarden) Livingston.[10]

He graduated from Princeton University in 1781.[10]

Career

Livingston was admitted to the bar in 1785, and began to practice law in New York City along with James Kent, Aaron Burr and Alexander Hamilton, rapidly rising to distinction.[11] From 1795 to 1801, Livingston was a Democratic-Republican U.S. Representative in the United States Congress from the state of New York, where he was one of the leaders of the opposition to Jay's Treaty, and introduced the resolution calling upon President George Washington to furnish Congress with the details of the negotiations of the peace treaty with the Kingdom of Great Britain, which the President refused to share. At the close of Washington's administration, he voted with Andrew Jackson and other radicals against the address to the president.[12]

Livingston was a prominent opponent of the Alien and Sedition Laws, introduced legislation on behalf of American seamen, and in 1800 attacked the president for permitting the extradition to the British government of Jonathan Robbins, who had committed murder on an English frigate and then escaped to South Carolina and falsely claimed to be an American citizen. In the debate on this question Livingston was opposed by John Marshall, the Chief Justice of the United States.[12]

In 1801, Livingston was appointed United States Attorney for the district of New York, and while retaining that position was in the same year appointed Mayor of New York City. When, in the summer of 1803, the city was visited with yellow fever, Livingston displayed courage and energy in his endeavors to prevent the spread of the disease and relieve distress. He suffered a violent attack of fever, during which the people gave many proofs of their attachment to him.[13]

Upon his recovery he found his private affairs in some confusion, and he was at the same time deeply indebted to the government for public funds which had been lost through the mismanagement or dishonesty of a confidential clerk, and for which he was responsible as US attorney. He at once surrendered all his property, resigned his two offices in 1803, and moved early in 1804 to New Orleans in what would shortly become the Territory of Orleans (1804–1812).[14] His older brother, Robert R. Livingston, had negotiated the Louisiana Purchase, in 1803. Edward Livingston soon built a large law practice in New Orleans, and in 1826 he repaid the Federal government in full, including the interest, which by that time amounted to more than the original principal.[14]

Louisiana

Almost immediately upon his arrival in Louisiana, where the legal system had previously been based on Roman, French, and Spanish law, and where trial by jury and other particularities of English common law were now first introduced, he was appointed by the legislature to prepare a provisional code of judicial procedure, which (in the form of an act passed in April 1805) was continued in force from 1805 to 1825.[14]

In 1807, after conducting a successful suit on behalf of a client's title to a part of the batture or alluvial land near New Orleans, Livingston attempted to improve part of this land (which he had received as his fee) in the Batture Ste. Marie. Great popular excitement was aroused against him; his workmen were mobbed; and territorial Governor William C. C. Claiborne, when appealed to for protection, referred the question to the Federal government.[14]

It has been alleged that Livingston's case was damaged by then-President Thomas Jefferson, who believed that Livingston had favored Aaron Burr in the Presidential election of 1800, and that he had afterwards been a party to Burr's schemes. Jefferson made it impossible for Livingston to secure his property title,[14] since by asserting the claim that such battures were the property of the Federal government, Livingston's title obtained from the Territorial Court was invalid. In response, Livingston filed a civil lawsuit against Jefferson in 1810. After the case was dismissed on December 5, 1811 by Chief Justice John Marshall due to lack of jurisdiction,[15] Jefferson, nonetheless, in 1812 published a pamphlet originally intended "for the use of counsel" in the case against Livingston, to which Livingston published a reply.

Louisiana became a U.S. state just one and a half months before the U.S. Congress declared war upon Great Britain. During the War of 1812, Edward Livingston was active in rousing the ethnically-mixed population of New Orleans to resistance against the threat of British invasion. He used his influence to secure amnesty for Jean Lafitte and his followers when they offered to help defend the city, and in 1814–15 acted as adviser and one of several aides-de-camp to Major General Andrew Jackson, who was his personal friend.[14]

Livingston Code

In 1821, by appointment of the Louisiana State Legislature, of which he had become a member of the Louisiana House of Representatives in the preceding year, Livingston began the preparation of a new code of criminal law and procedure, afterwards known in Europe and America as the "Livingston Code." It was prepared in both French and English, as was required by the necessities of practice in Louisiana, and actually consisted of four sections: crimes and punishments, procedure, evidence in criminal cases, and reform and prison discipline. Though substantially completed in 1824, when it was accidentally burned, and again in 1826, the criminal code was not printed in its entirety until 1833. It was never adopted by the state.[14]

The Livingston Code was at once reprinted in England, France, and Germany, attracting wide praise by its remarkable simplicity and vigor, and especially by reason of its philanthropic provisions in the code of reform and prison discipline, which noticeably influenced the penal legislation of various countries. In referring to this code, Sir Henry Maine spoke of Livingston as "the first legal genius of modern times."[16] The spirit of Livingston's code was remedial rather than vindictive; it provided for the abolition of capital punishment and the making of penitentiary labor not a punishment forced on the prisoner, but a matter of his choice and a reward for good behavior, bringing with it better accommodations. His Code of Reform and Prison Discipline was adopted by the government of the short-lived Federal Republic of Central America under liberal president Francisco Morazán.[14]

Livingston was the leading member of a commission appointed to prepare a new civil code for Louisiana, which for the most part the legislature adopted in 1825; and the most important chapters of which, including all those on contracts, were prepared by Edward Livingston alone. Livingston became again a U.S. Representative, this time as the first person to serve Louisiana's 1st congressional district. The preliminary work for the preparation of a new civil code was completed by James Brown and Louis Moreau-Lislet, who in 1808 reported a Digest of the Civil Laws now in force in the Territory of Orleans with Alterations and Amendments adapted to the present Form of Government.[14]

Later career

Livingston served as a U.S. Representative from Louisiana from 1823 to 1829, a U.S. Senator from 1829 to 1831, and for two years (1831–1833) United States Secretary of State under President Jackson. In this last position he was one of Jackson's most trusted advisers. Livingston prepared a number of state papers for President Jackson, the most important being the famous anti-nullification proclamation of December 10, 1832.[14]

From 1833 to 1835, Livingston was minister plenipotentiary to France, charged with procuring the fulfillment by the French government of the treaty negotiated by W. C. Rives in 1831, by which France had bound herself to pay an indemnity of twenty-five millions of francs for French spoliations of American shipping chiefly under the Berlin and Milan decrees, and the United States in turn agreed to pay to France 1,500,000 francs in satisfaction of French claims. Livingston's negotiations were conducted with excellent judgment, but the French Chamber of Deputies refused to make an appropriation to pay the first installment due under the treaty in 1833, relations between the two governments became strained, and Livingston was finally instructed to close the legation and return to America.[14]

Personal life

Livingston was married twice. His first wife, Mary McEvers, whom he wed on April 10, 1788, later died of scarlet fever.[10] She was the daughter of Charles McEvers and Mary (née Bache) McEvers and her sister, Eliza McEvers, was the second wife of Edwards older brother, the merchant John R. Livingston.[10] Before her death on March 13, 1801, they were the parents of three children:[11]

- Charles Edward Livingston (born 1790)

- Julia Livingston (born 1794)

- Lewis Livingston (1798–1822)

In June 1805, he married Madame Marie Louise Magdaleine Valentine "Louise" (née d'Avezac) de Castera Moreau de Lassy (1785–1860), a widow who was then only 19 years of age, and a refugee in New Orleans from the Haitian Revolution.[17] She was the daughter of a wealthy landowner and the sister of Auguste Davezac, a politician and diplomat who served twice as U.S. Minister to the Netherlands. She was a woman of extraordinary beauty and intellect: "the lady name is short, but she is said to be majestic in her person and elegant in manners with a long purse".[18] She is said to have greatly influenced her husband's public career.[14] Together, Louise and Edward were the parents of two children, only one of whom lived to adulthood:[10]

- Coralie Livingston (1806–1873), who married Thomas Pennant Barton (1803–1869), the son of noted physician Benjamin Smith Barton, in April 1833.[10]

Livingston died on May 23, 1836 at Montgomery Place in Rhinebeck, New York, an estate left him by his sister, to which he had removed in 1831.[10]

Legacy and honors

The town of Livingston, Guatemala, is named after Edward Livingston, in commemoration of the Livingston Code.

Edward Livingston is the namesake of counties in Illinois, Michigan, and Missouri,[19] and a parish in Louisiana with its seat of Livingston. Also named for him is a town in Tennessee, a town in Livingston, Alabama, a Sumter County, Alabama, and by extension, the town of Livingston, Texas, Lake Livingston in Texas, and the Livingston Dam.

Edward Livingston High School[20] (formerly a middle school) in New Orleans was named for him. Fort Livingston, a 19th-century coastal fortification, was named after Edward Livingston, along with today's Fort Livingston State Commemorative Area in south Louisiana.

In 1833, Livingston was elected a member of the American Antiquarian Society.[21]

References

- Lawrence Friedman, A History of American Law (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2005), p. 118. Louisiana, along with Scotland and Quebec, is one of a few "mixed" jurisdictions whose law derives from both the civil and the common law traditions.

- U.S. Department of State, "Secretary of State Edward Livingston" (July 15, 2003), http://history.state.gov/departmenthistory/people/livingston-edward.

- "Livingston, Robert (1746-1813) to John R. Livingston". www.gilderlehrman.org. Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History. Retrieved January 17, 2018.

- Shelton, Hal T. (1996). General Richard Montgomery and the American Revolution: From Redcoat to Rebel. NYU Press. p. 38. ISBN 9780814780398. Retrieved January 17, 2018.

- "Friends of Clermont Historic Site". friendsofclermont.org. Friends of Clermont Historic Site. Retrieved January 17, 2018.

- Andrews, Dee E. (2010). The Methodists and Revolutionary America, 1760-1800: The Shaping of an Evangelical Culture. Princeton University Press. p. 302. ISBN 1400823595. Retrieved January 17, 2018.

- Clermont State Historic Site (May 16, 2016). "Clermont State Historic Site: Was John R. Livingston a Murderer?". Clermont State Historic Site. Retrieved January 17, 2018.

- "John R. Livingston (1755-1851)". www.nyhistory.org. New-York Historical Society. Retrieved January 17, 2018.

- Hess, Stephen (2017). America's Political Dynasties. Routledge. p. 552. ISBN 9781351532150. Retrieved January 17, 2018.

- Livingston, Edwin Brockholst (1910). The Livingstons of Livingston Manor: Being the History of that Branch of the Scottish House of Callendar which Settled in the English Province of New York During the Reign of Charles the Second; and Also Including an Account of Robert Livingston of Albany, "The Nephew," a Settler in the Same Province and His Principal Descendants. Knickerbocker Press. Retrieved August 10, 2017.

- Aitken, William Benford (1912). Distinguished Families in America, Descended from Wilhelmus Beekman and Jan Thomasse Van Dyke. Knickerbocker Press. pp. 51–52. Retrieved January 16, 2019.

- Chisholm 1911, p. 811.

- Chisholm 1911, pp. 811–812.

- Chisholm 1911, p. 812.

- See Dumas Malone's biography, Jefferson and His Time - Volume 6, The Sage of Monticello, ch. 5, "The Batture Controversy".

- Cambridge Essays, 1856, p. 17.

- Browning, Charles Henry (1891). Americans of Royal Descent: A Collection of Genealogies of American Families Whose Lineage is Traced to the Legitimate Issue of Kings. Porter & Costes. p. 167. Retrieved January 16, 2019.

- July 1805 Matrimony notice of Moreau de Lassy.

- Eaton, David Wolfe (1916). How Missouri Counties, Towns and Streams Were Named. The State Historical Society of Missouri. pp. 188.

- New Orleans Public Schools Superintendent's report of February 2013 page 13, accessed April 6, 2015.

- American Antiquarian Society Members Directory

Further reading

Hatcher, William B., Edward Livingston: Jeffersonian Republican and Jacksonian Democrat, Louisiana State University Press (1940).

External links

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: Edward Livingston |

- United States Congress. "Edward Livingston (id: L000366)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.

- Office of the Historian profile at U.S. Department of State

- Edward Livingston at Find a Grave

- Edward Livingston Letters at The Historic New Orleans Collection