Millard Fillmore

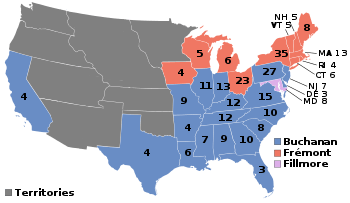

Millard Fillmore (January 7, 1800 – March 8, 1874) was the 13th president of the United States (1850–1853), the last to be a member of the Whig Party while in the White House. A former U.S. representative from New York, Fillmore was elected the nation's 12th vice president in 1848, and succeeded to the presidency in July 1850 upon the death of President Zachary Taylor. He was instrumental in the passing of the Compromise of 1850, a bargain that led to a brief truce in the battle over slavery. He failed to win the Whig nomination for president in 1852, but he gained the endorsement of the nativist Know Nothing Party four years later, finishing third in the 1856 presidential election.

Millard Fillmore | |

|---|---|

Photo by Mathew Brady, c. 1855–1865 | |

| 13th President of the United States | |

| In office July 9, 1850 – March 4, 1853 | |

| Vice President | None[lower-alpha 1] |

| Preceded by | Zachary Taylor |

| Succeeded by | Franklin Pierce |

| 12th Vice President of the United States | |

| In office March 4, 1849 – July 9, 1850 | |

| President | Zachary Taylor |

| Preceded by | George M. Dallas |

| Succeeded by | William R. King |

| Chairman of the House Ways and Means Committee | |

| In office March 4, 1841 – March 3, 1843 | |

| Preceded by | John Winston Jones |

| Succeeded by | James I. McKay |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from New York's 32nd district | |

| In office March 4, 1837 – March 3, 1843 | |

| Preceded by | Thomas C. Love |

| Succeeded by | William A. Moseley |

| In office March 4, 1833 – March 3, 1835 | |

| Preceded by | Constituency established |

| Succeeded by | Thomas C. Love |

| 14th Comptroller of New York | |

| In office January 1, 1848 – February 20, 1849 | |

| Governor | |

| Preceded by | Azariah Cutting Flagg |

| Succeeded by | Washington Hunt |

| Personal details | |

| Born | January 7, 1800 Moravia, New York, U.S. |

| Died | March 8, 1874 (aged 74) Buffalo, New York, U.S. |

| Resting place | Forest Lawn Cemetery Buffalo, New York |

| Political party |

|

| Spouse(s) | |

| Children | Millard and Mary |

| Parents |

|

| Profession | Lawyer |

| Signature | |

| Military service | |

| Branch/service | |

| Years of service |

|

| Rank | |

| Commands | Union Continentals (New York Guard) |

| Battles/wars | American Civil War |

Fillmore was born into poverty in the Finger Lakes area of New York state—his parents were tenant farmers during his formative years. Though he had little formal schooling, he rose from poverty through diligent study and became a successful attorney. He became prominent in the Buffalo area as an attorney and politician, and was elected to the New York Assembly in 1828, and to the U.S. House of Representatives in 1832. Initially, he belonged to the Anti-Masonic Party, but became a Whig as the party formed in the mid-1830s; he was a rival for state party leadership with editor Thurlow Weed and Weed's protégé, William H. Seward. Throughout his career, Fillmore declared slavery an evil, but one beyond the powers of the federal government, whereas Seward was not only openly hostile to slavery, he argued that the federal government had a role to play in ending it. Fillmore was an unsuccessful candidate for Speaker of the House when the Whigs took control of the chamber in 1841 but was made Ways and Means Committee chairman. Defeated in bids for the Whig nomination for vice president in 1844, and for New York governor the same year, Fillmore was elected Comptroller of New York in 1847, the first to hold that post by direct election.

As vice president, Fillmore was largely ignored by Taylor, even in the dispensing of patronage in New York, on which Taylor consulted Weed and Seward. In his capacity as President of the Senate, however, he presided over angry debates there as Congress decided whether to allow slavery in the Mexican Cession. Fillmore supported Henry Clay's Omnibus Bill (the basis of the 1850 Compromise) though Taylor did not. Upon becoming president in July 1850, Fillmore dismissed Taylor's cabinet and pushed Congress to pass the Compromise. The Fugitive Slave Act, expediting the return of escaped slaves to those who claimed ownership, was a controversial part of the Compromise. Fillmore felt himself duty-bound to enforce it, though it damaged his popularity and also the Whig Party, which was torn North from South. In foreign policy Fillmore supported U.S. Navy expeditions to open trade in Japan, opposed French designs on Hawaii, and was embarrassed by Narciso López's filibuster expeditions to Cuba. He sought election to a full term in 1852 but was passed over by the Whigs in favor of Winfield Scott.

As the Whig Party broke up after Fillmore's presidency, many in Fillmore's conservative wing joined the Know Nothings, forming the American Party. In his 1856 candidacy as that party's nominee Fillmore had little to say about immigration, focusing instead on the preservation of the Union, and won only Maryland. During the American Civil War, Fillmore denounced secession and agreed that the Union must be maintained by force if necessary, but was critical of the war policies of Abraham Lincoln. After peace was restored, he supported the Reconstruction policies of President Andrew Johnson. In retirement, Fillmore remained involved in civic interests, including as chancellor of the University of Buffalo, which he had helped found in 1846; he is largely obscure today.

Early life and career

Millard Fillmore was born on January 7, 1800, in a log cabin,[lower-alpha 2] on a farm in what is now Moravia, Cayuga County, in the Finger Lakes region of New York. His parents were Phoebe Millard and Nathaniel Fillmore[2]—he was the second of eight children and the oldest son.[3] Nathaniel Fillmore was the son of Nathaniel Fillmore Sr. (1739–1814), a native of Franklin, Connecticut, who became one of the earliest settlers of Bennington, Vermont, when it was founded in the territory then called the New Hampshire Grants.[4]

Nathaniel Fillmore and Phoebe Millard moved from Vermont in 1799, seeking better opportunities than were available on Nathaniel's stony farm, but the title to their Cayuga County land proved defective, and the Fillmore family moved to nearby Sempronius, where they leased land as tenant farmers, and Nathaniel occasionally taught school.[5][6] Historian Tyler Anbinder described Fillmore's childhood as "... one of hard work, frequent privation, and virtually no formal schooling".[2]

Over time, Nathaniel became more successful in Sempronius, though during Millard's formative years the family endured severe poverty.[lower-alpha 3] Nathaniel became sufficiently regarded that he was chosen to serve in local offices including justice of the peace.[9] In hopes his oldest son would learn a trade, he convinced Millard at age fourteen not to enlist for the War of 1812[10] and apprenticed him to cloth maker Benjamin Hungerford in Sparta.[11] Fillmore was relegated to menial labor; unhappy at not learning any skills, he left Hungerford's employ.[12] His father then placed him in the same trade at a mill in New Hope.[13] Seeking to better himself, Millard bought a share in a circulating library and read all the books he could.[13] In 1819, he took advantage of idle time at the mill to enroll at a new academy in the town, where he met a classmate, Abigail Powers, and fell in love with her.[14]

Later in 1819, Nathaniel moved the family to Montville, a hamlet of Moravia.[15] Appreciating his son's talents, Nathaniel followed his wife's advice and persuaded Judge Walter Wood, the Fillmores' landlord and the wealthiest person in the area, to allow Millard to be his law clerk for a trial period.[16] Wood agreed to employ young Fillmore and to supervise him as he read law.[16] Fillmore earned money teaching school for three months and bought out his mill apprenticeship.[17] He left Wood after 18 months—the judge paid him almost nothing—and the two quarreled after Fillmore, unaided, earned a small sum advising a farmer in a minor lawsuit.[18] Refusing to pledge not to do it again, Fillmore gave up his clerkship.[19] Nathaniel again moved the family, and Millard accompanied them west to East Aurora, in Erie County, near Buffalo.[20] There Nathaniel purchased a farm which became prosperous.[21]

In 1821, Fillmore turned 21 and reached adulthood.[22] He taught school in East Aurora and accepted a few cases in justice of the peace courts, which did not require the practitioner to be a licensed attorney.[22] He moved to Buffalo the following year and continued his study of law—first while teaching school, and then in the law office of Asa Rice and Joseph Clary. At that time he also became engaged to Abigail Powers.[22] In 1823, he was admitted to the New York bar, declined offers from Buffalo law firms, and returned to East Aurora to establish a practice as the town's only resident lawyer.[20][23] Later in life, Fillmore said that initially he lacked the self-confidence to practice in the larger city of Buffalo; his biographer, Paul Finkelman, suggested that after being under others' thumbs all his life, Fillmore enjoyed the independence of his East Aurora practice.[24] Millard and Abigail wed on February 5, 1826. They would have two children, Millard Powers Fillmore (1828–1889) and Mary Abigail Fillmore (1832–1854).[25]

Buffalo politician

Other members of the Fillmore family were active in politics and government in addition to Nathaniel's service as a justice of the peace. Millard's grandfather, Nathaniel Sr., served in local offices in Bennington—as hayward ("hedge warden"), highway surveyor and tax collector.[26][lower-alpha 4] Millard then also became interested in politics—the rise of the Anti-Masonic Party in the late 1820s provided his initial attraction and entry.[29]

| External video | |

|---|---|

Many Anti-Masons were opposed to the presidential candidacy of General Andrew Jackson, a Mason. Fillmore was a delegate to the New York convention that endorsed President John Quincy Adams for re-election and also served at two Anti-Masonic conventions in the summer of 1828.[2] At the conventions, Fillmore and one of the early political bosses, newspaper editor Thurlow Weed, met and impressed each other.[29] By then, Fillmore was the leading citizen in East Aurora. He successfully sought election to the New York State Assembly and served in Albany for three one-year terms (1829 to 1831).[2] Fillmore's 1828 election was in contrast to the victories of the Jacksonian Democrats (soon the Democrats), who swept the general into the White House and their party to a majority in Albany—thus Fillmore was in the minority in the Assembly.[30] He proved effective anyway, promoting legislation to provide court witnesses the option of taking a non-religious oath, and in 1830 abolishing imprisonment for debt.[10] By then, much of Fillmore's legal practice was in Buffalo and later that year he moved there with his family; he did not seek re-election in 1831.[29][31]

Fillmore was also successful as a lawyer. Buffalo was then in a period of rapid expansion, recovering from British conflagration during the War of 1812 and becoming the western terminus of the Erie Canal. Court cases from outside Erie County began falling to Fillmore's lot, and he reached prominence as a lawyer in Buffalo before he moved there. He took his lifelong friend Nathan K. Hall as a law clerk in East Aurora—Hall became Fillmore's partner in Buffalo and his postmaster general as president. Buffalo was legally a village when Fillmore arrived, and although the bill to incorporate it as a city passed the legislature after Fillmore had left the Assembly, he helped draft the city charter. In addition to his legal practice, Fillmore helped found the Buffalo High School Association, joined the lyceum and attended the local Unitarian church; he became a leading citizen of Buffalo.[32] He was also active in the New York Militia and attained the rank of major as inspector of the 47th Brigade.[33][34]

Congressman

First term; return to Buffalo

In 1832, Fillmore ran successfully for the House of Representatives. The Anti-Masonic presidential candidate, William Wirt, former attorney general, won only Vermont, as President Jackson easily gained re-election. At the time, Congress convened its annual session in December, and so Fillmore had to wait more than a year after his election to take his seat. Fillmore, Weed, and others realized that opposition to Masonry was too narrow a foundation on which to build a national party. They formed the broad-based Whig Party from National Republicans, Anti-Masons, and disaffected Democrats. The Whigs were initially united by their opposition to Jackson, but became a major party by expanding their platform to include support for economic growth through rechartering the Second Bank of the United States and federally funded internal improvements including roads, bridges, and canals.[35] Weed joined the Whigs before Fillmore and became a power within the party; his anti-slavery views were stronger than Fillmore's (who disliked slavery but considered the federal government powerless over it), and closer to those of another prominent New York Whig, William H. Seward of Auburn, who was also seen as a Weed protégé.[3]

In Washington, Fillmore urged the expansion of Buffalo harbor, a decision under federal jurisdiction, and privately lobbied Albany for the expansion of the state-owned Erie Canal.[36] Even during the 1832 campaign, Fillmore's affiliation as an Anti-Mason had been uncertain, and he rapidly shed the label once sworn in. Fillmore came to the notice of the influential Massachusetts senator Daniel Webster, who took the new congressman under his wing. Fillmore became a firm supporter, and the close relationship between the two would continue until Webster's death late in Fillmore's presidency.[37] Despite Fillmore's support of the Second Bank as a means for national development, he did not speak in the congressional debates in which some advocated renewing its charter, although Jackson had previously vetoed legislation for a charter renewal.[38] Fillmore supported building infrastructure, voting in favor of navigation improvements on the Hudson River and constructing a bridge across the Potomac River.[39]

Anti-Masonry was still strong in Western New York, though it was petering out nationally. When the Anti-Masons did not nominate him for a second term in 1834, Fillmore declined the Whig nomination, seeing that the two parties would split the anti-Jackson vote and elect the Democrat. Despite Fillmore's departure from office, he was a rival for state party leadership with Seward, the unsuccessful 1834 Whig gubernatorial candidate.[40] Fillmore spent his time out of office building his law practice and boosting the Whig Party, which gradually absorbed most of the Anti-Masons.[41] By 1836 Fillmore was confident enough of anti-Jackson unity that he accepted the Whig nomination for Congress. Democrats, led by their presidential candidate, Vice President Martin Van Buren, were victorious nationwide and in Van Buren's home state of New York, but Western New York voted Whig and sent Fillmore back to Washington.[42]

Second through fourth terms

Van Buren, faced with the economic Panic of 1837, caused in part by lack of confidence in private banknote issues after Jackson had instructed the government to accept only gold or silver, called a special session of Congress. Government money had been held in so-called "pet banks" since Jackson had withdrawn it from the Second Bank; Van Buren proposed to place funds in sub-treasuries, government depositories that would not lend money. Believing that government funds should be lent to develop the country, Fillmore felt this would lock the nation's limited supply of gold money away from commerce. Van Buren's sub-treasury and other economic proposals passed, but as hard times continued, the Whigs saw an increased vote in the 1837 elections and captured the New York Assembly. This set up a fight for the 1838 gubernatorial nomination. Fillmore supported the leading Whig vice-presidential candidate from 1836, Francis Granger; Weed preferred Seward. Fillmore was embittered when Weed got the nomination for Seward but campaigned loyally; Seward was elected, while Fillmore won another term in the House.[43]

The rivalry between Fillmore and Seward was affected by the growing anti-slavery movement. Although Fillmore disliked slavery, he saw no reason it should be a political issue. Seward, however, was hostile to slavery and made that clear in his actions as governor, refusing to return slaves claimed by Southerners.[43] When the Buffalo bar proposed Fillmore for the position of vice-chancellor of the eighth judicial district in 1839, Seward refused and nominated Frederick Whittlesey—indicating that if the state senate rejected Whittlesey, he still would not appoint Fillmore.[44]

Fillmore was active in the discussions of presidential candidates that preceded the Whig National Convention for the 1840 race. He initially supported General Winfield Scott, but really wanted to defeat Kentucky Senator Henry Clay, a slaveholder he felt could not carry New York state. Fillmore did not attend the convention, but was gratified when it nominated General William Henry Harrison for president, with former Virginia senator John Tyler his running mate.[45] Fillmore organized Western New York for the Harrison campaign, and the national ticket was elected, while Fillmore easily gained a fourth term in the House.[46]

At the urging of Senator Clay, Harrison quickly called a special session of Congress. With the Whigs able to organize the House for the first time, Fillmore sought the Speakership, but it went to a Clay acolyte, John White of Kentucky.[47] Nevertheless, Fillmore was made chairman of the House Ways and Means Committee.[2] Harrison was expected to go along with anything Clay and other congressional Whig leaders proposed, but died on April 4, 1841, elevating Vice President Tyler to the presidency. Tyler, a onetime maverick Democrat, soon broke with Clay over congressional proposals for a national bank to stabilize the currency, which he vetoed twice, leading to his expulsion from the Whig Party. Fillmore remained on the fringes of that conflict, generally supporting the congressional Whig position, but his chief achievement as Ways and Means chairman was the Tariff of 1842. The existing tariff did not protect manufacturing, and part of the revenue was distributed to the states, a decision made in better times that was by then depleting the Treasury. Fillmore prepared a bill raising tariff rates that was popular in the country, but the continuation of distribution assured a Tyler veto and much political advantage for the Whigs. Once Tyler vetoed it, a House committee headed by Massachusetts' John Quincy Adams condemned his actions. Fillmore prepared a second bill, this time omitting distribution, and when it reached his desk, Tyler signed it, but in the process offended his erstwhile Democratic allies. Thus, Fillmore not only achieved his legislative goal but managed to isolate Tyler politically.[48]

Fillmore received praise for the tariff, but in July 1842 he announced he would not seek re-election. The Whigs nominated him anyway, but he refused it. Tired of Washington life and the conflict that had revolved around President Tyler, Fillmore sought to return to his life and law practice in Buffalo. He continued to be active in the lame duck session of Congress that followed the 1842 elections and returned to Buffalo in April 1843. According to his biographer, Scarry: "Fillmore concluded his Congressional career at a point when he had become a powerful figure, an able statesman at the height of his popularity".[49] Thurlow Weed deemed Congressman Fillmore "able in debate, wise in council, and inflexible in his political sentiments".[50]

National figure

Out of office, Fillmore continued his law practice and made long-neglected repairs to his Buffalo home. He remained a major political figure, leading the committee of notables that welcomed John Quincy Adams to Buffalo. The former president expressed his regret at Fillmore's absence from the halls of Congress. Some urged Fillmore to run for vice president with Clay, the consensus Whig choice for president in 1844. Horace Greeley wrote privately that "my own first choice has long been Millard Fillmore"; others thought Fillmore should try to win back the governor's mansion for the Whigs.[51] Seeking to return to Washington, Fillmore wanted the vice presidency.[52]

Fillmore hoped to gain the endorsement of the New York delegation to the national convention, but Weed wanted the vice presidency for Seward, with Fillmore as governor. Seward, however, withdrew before the 1844 Whig National Convention. When Weed's replacement vice presidential hopeful, Willis Hall, fell ill, Weed sought to defeat Fillmore's candidacy to force him to run for governor. Weed's attempts to boost Fillmore as a gubernatorial candidate caused the former congressman to write, "I am not willing to be treacherously killed by this pretended kindness ... do not suppose for a minute that I think they desire my nomination for governor."[53] New York sent a delegation to the convention in Baltimore pledged to support Clay, but with no instructions as to how to vote for vice president. Weed told out-of-state delegates that the New York party preferred to have Fillmore as its gubernatorial candidate, and after Clay was nominated for president, the second place on the ticket fell to former New Jersey senator Theodore Frelinghuysen.[54]

Putting a good face on his defeat, Fillmore met and publicly appeared with Frelinghuysen, quietly spurning Weed's offer to get him nominated as governor at the state convention. Fillmore's position in opposing slavery, but only at the state level, made him acceptable as a statewide Whig candidate, and Weed saw to it the pressure on Fillmore increased. Fillmore had stated previously that a convention had the right to draft anyone for political service, and Weed got the convention to choose Fillmore, who had broad support, despite his reluctance.[55]

The Democrats nominated Senator Silas Wright as their gubernatorial candidate and former Tennessee governor James K. Polk for president. Although Fillmore worked to gain support among German-Americans, a major constituency, he was hurt among immigrants by the fact that New York City Whigs had supported a nativist candidate in the mayoral election earlier in 1844—Fillmore and his party were tarred with that brush.[56] He was not friendly to immigrants and blamed his defeat on "foreign Catholics".[57] Clay was beaten as well.[55] Fillmore's biographer Paul Finkelman suggested that Fillmore's hostility to immigrants and his weak position on slavery defeated him for governor.[58]

In 1846, Fillmore was involved in the founding of what is now the University at Buffalo (earlier the University of Buffalo) and became its first chancellor; he served until his death in 1874. He had opposed the annexation of Texas, and spoke against the subsequent Mexican–American War, seeing it as a contrivance to extend slavery's realm. Fillmore was angered when President Polk vetoed a river and harbors bill that would have benefited Buffalo,[59] and wrote, "May God save the country for it is evident the people will not."[60] At the time, New York governors served a two-year term, and Fillmore could have had the Whig nomination in 1846, had he wanted it. He actually came within one vote of it while maneuvering to get the nomination for his supporter, John Young, who was elected. A new constitution for New York state provided that the office of comptroller was made elective, as were the attorney general and some other positions that were formerly chosen by the state legislature. Fillmore's work in finance while Ways and Means chairman made him an obvious candidate for comptroller, and he was successful in getting the Whig nomination for the 1847 election.[61] With a united party at his back, Fillmore won by 38,000 votes, the largest margin a Whig candidate for statewide office would ever achieve in New York.[62]

Before moving to Albany to take office on January 1, 1848, he left his law firm and rented out his house. Fillmore received positive reviews for his service as comptroller. In that office, he was a member of the state canal board, supported its expansion and saw that it was managed competently. He secured an enlargement of Buffalo's canal facilities. The comptroller regulated the banks, and Fillmore stabilized the currency by requiring that state-chartered banks keep New York and federal bonds to the value of the banknotes they issued—a similar plan was adopted by Congress in 1864.[63]

Election of 1848

Nomination

President Polk had pledged not to seek a second term, and with gains in Congress during the 1846 election cycle, the Whigs were hopeful of taking the White House in 1848. The party's perennial candidates, Henry Clay and Daniel Webster, each wanted the nomination and amassed support from congressional colleagues. Many rank and file Whigs backed the Mexican War hero, General Zachary Taylor, for president. Although Taylor was extremely popular, many northerners had qualms about electing a Louisiana slaveholder at a time of sectional tension over whether slavery should be allowed in the territories ceded by Mexico. Taylor's uncertain political views gave others pause—career Army, he had never cast a ballot for president, though he stated that he was a Whig supporter, and some feared they might elect another Tyler, or another Harrison.[64]

With the nomination undecided, Weed maneuvered for New York to send an uncommitted delegation to the 1848 Whig National Convention in Philadelphia, hoping to be a kingmaker in position to place former governor Seward on the ticket or to get him high national office. He persuaded Fillmore to support an uncommitted ticket, though he did not tell the Buffaloan of his hopes for Seward. Weed was an influential editor, and Fillmore tended to cooperate with him for the greater good of the Whig Party. But Weed had sterner opponents, including Governor Young, who disliked Seward and did not want to see him gain high office.[65]

Despite Weed's efforts, Taylor was nominated on the fourth ballot, to the anger of Clay's supporters and of Conscience Whigs from the Northeast. When order was restored, John A. Collier, a New Yorker and a Weed opponent, addressed the convention. Delegates hung on his every word as he described himself as a Clay partisan; he had voted for Clay on each ballot. He eloquently described the grief of the Clay supporters, frustrated again in their battle to make Clay president. Collier warned of a fatal breach in the party and stated that only one thing could prevent it: the nomination of Fillmore for vice president, whom he depicted incorrectly as a strong Clay supporter. Fillmore in fact agreed with many of Clay's positions, but did not back him for president, and was not in Philadelphia. Delegates did not know this was false, or at least greatly exaggerated, and there was a large reaction in Fillmore's favor. At the time, the presidential candidate did not automatically pick his running mate, and despite the efforts of Taylor's managers to get the nomination for their choice, Abbott Lawrence of Massachusetts, Fillmore became the Whig nominee for vice president on the second ballot.[66]

Weed had wanted the vice-presidential nomination for Seward (who attracted few delegate votes), and Collier had acted to frustrate them in more ways than one, for with the New Yorker Fillmore as vice president, under the political customs of the time, no one from that state could be named to the cabinet. Fillmore was accused of complicity in Collier's actions, but this was never substantiated.[67] Nevertheless, there were sound reasons for Fillmore's selection, as he was a proven vote-getter from electorally crucial New York, and his track record in Congress and as a candidate showed his devotion to Whig doctrine, allaying fears he might be another Tyler were something to happen to General Taylor. Delegates remembered him for his role in the Tariff of 1842, and he had been mentioned as a vice-presidential possibility along with Lawrence and Ohio's Thomas Ewing. His rivalry with Seward (already known for anti-slavery views and statements) made him more acceptable in the South.[68][69]

General election campaign

It was customary in mid-19th century America for a candidate for high office not to appear to seek it. Thus, Fillmore remained at the comptroller's office in Albany and made no speeches; the 1848 campaign was conducted in the newspapers and with addresses made by surrogates at rallies. The Democrats nominated Senator Lewis Cass of Michigan for president, with General William O. Butler as his running mate, but it became a three-way fight as the Free Soil Party, opposed to the spread of slavery, chose former president Van Buren.[70] There was a crisis among the Whigs when Taylor also accepted the presidential nomination of a group of dissident South Carolina Democrats. Fearing that Taylor would be a party apostate like Tyler, Weed in late August scheduled a rally in Albany aimed at electing an uncommitted slate of presidential electors. Fillmore interceded with the editor, assuring him that Taylor was loyal to the party.[71][72]

Northerners assumed that Fillmore, hailing from a free state, was an opponent of the spread of slavery. Southerners accused him of being an abolitionist, which he hotly denied.[73] Fillmore responded to one Alabamian in a widely published letter that slavery was an evil, but one that the federal government had no authority over.[71] Taylor and Fillmore corresponded twice in September, with the general happy that the crisis over the South Carolinians was resolved. Fillmore, for his part, assured his running mate that the electoral prospects for the ticket looked good, especially in the Northeast.[74]

In the end, the Taylor/Fillmore ticket won narrowly, with New York's electoral votes again key to the election.[75] The Whig ticket won the popular vote by 1,361,393 (47.3 percent) to 1,223,460 (42.5 percent) and triumphed 163 to 127 in the Electoral College.[lower-alpha 5] Minor party candidates took no electoral votes,[76] but the strength of the burgeoning anti-slavery movement was shown by the vote for Van Buren, who, though he won no states, earned 291,501 votes (10.1 percent), and finished second in New York, Vermont and Massachusetts.[77]

Vice president (1849–1850)

Millard Fillmore was sworn in as vice president on March 5, 1849, in the Senate Chamber. March 4 (then Inauguration Day) fell on a Sunday, so the swearing-in was postponed until the following day. Fillmore took the oath from Chief Justice Roger B. Taney and in turn swore in the senators beginning their terms, including Seward, who in February had been elected by the New York legislature.[lower-alpha 6]

Fillmore had spent the four months between the election and swearing-in being feted by the New York Whigs and winding up affairs in the comptroller's office. Taylor had written to him, promising influence in the new administration; the president-elect mistakenly thought that the vice president was a cabinet member, which was not true in the 19th century. Fillmore, Seward and Weed had met and come to general agreement on how to divide federal jobs in New York. Once he went to Washington, Seward made friendly contact with Taylor's cabinet nominees, advisers, and the general's brother. An alliance between the incoming administration and the Weed machine was soon under way behind Fillmore's back. In exchange for support, Seward and Weed were allowed to designate who was to fill federal jobs in New York, with Fillmore given far less influence than had been agreed. When Fillmore discovered this after the election, he went to Taylor, which only made the warfare against Fillmore's influence more open. Fillmore supporters like Collier, who had nominated him at the convention, were passed over for candidates backed by Weed, who was triumphant even in Buffalo. This greatly increased Weed's influence in New York politics and diminished Fillmore's. According to Rayback, "by mid-1849, Fillmore's situation had become desperate."[78] Despite his lack of influence, office seekers pestered him, as did those with a house to lease or sell, for there was then no official vice-presidential residence. He enjoyed one aspect of his office, due to his lifelong love of learning: he became deeply involved in the administration of the Smithsonian Institution as a member ex officio of its Board of Regents.[79]

Through 1849, the slavery issue was unresolved in the territories. Taylor advocated the admission of California and New Mexico,[lower-alpha 7] both likely to outlaw slavery. Southerners were surprised to learn the president, despite being a Southern slaveholder, did not support the introduction of slavery into the new territories, as he believed the institution could not flourish in the arid Southwest. There was anger across party lines in the South, where making the territories free of slavery was considered excluding Southerners from part of the national heritage. When Congress met in December 1849, this discord was manifested in the election for Speaker, which took weeks and dozens of ballots to resolve as the House divided along sectional lines.[80][81]

Fillmore countered the Weed machine by building a network of like-minded Whigs in New York state; with backing from wealthy New Yorkers, their positions were publicized by the establishment of a rival newspaper to Weed's Albany Evening Journal. All pretense at friendship between Fillmore and Weed vanished in November 1849 when the two happened to meet in New York City, and they exchanged accusations.[82]

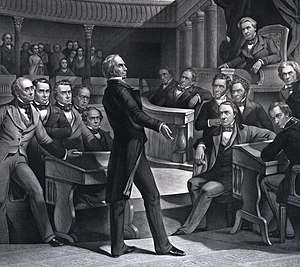

Fillmore presided[lower-alpha 8] over some of the most momentous and passionate debates in American history as the Senate debated whether to allow slavery in the territories. The ongoing sectional conflict had already excited much discussion when on January 21, 1850, President Taylor sent a special message to Congress urging the admission of California immediately and New Mexico later, and that the Supreme Court settle the boundary dispute whereby the state of Texas claimed much of what is now the state of New Mexico.[83] On January 29, Henry Clay introduced what was called the "Omnibus Bill".[lower-alpha 9] The bill would give victories to both North and South: it would admit California as a free state, organize territorial governments in New Mexico and Utah, and ban the importation of slaves into the District of Columbia for sale and export out of it. It would also toughen the Fugitive Slave Act, as resistance to enforcement in parts of the North was a longtime Southern grievance. Clay's bill provided for the settlement of the Texas-New Mexico boundary dispute; the status of slavery in the territories would be decided by those living there (known as popular sovereignty). Taylor was unenthusiastic about the bill, and it languished in Congress. After hearing weeks of debate, however, Fillmore informed him in May 1850 that if senators divided equally on the bill, he would cast his tie-breaking vote in favor.[2] Fillmore did his best to keep the peace among the senators, reminding them of the vice president's power to rule them out of order, but was blamed for failing to maintain it when a physical confrontation between Mississippi's Henry S. Foote and Missouri's Thomas Hart Benton broke out on April 17. Before other senators intervened to separate them, Foote pointed a gun at his colleague as Benton advanced on him.[84]

Presidency (1850–1853)

Succession amid crisis

July 4, 1850 was a very hot day in Washington, and President Taylor, who attended Fourth of July ceremonies to lay the cornerstone of the Washington Monument, refreshed himself, likely with cold milk and cherries. What he consumed probably gave him gastroenteritis, and he died on July 9. Taylor, nicknamed "Old Rough and Ready", had gained a reputation for toughness through his military campaigning in the heat, and his sudden death came as a shock to the nation.[85]

Fillmore had been called from his chair presiding over the Senate on July 8 and had sat with members of the cabinet in a vigil outside Taylor's bedroom at the White House. He received the formal notification of the president's death, signed by the cabinet, on the evening of July 9 in his residence at the Willard Hotel. After acknowledging the letter, and spending a sleepless night,[86] Fillmore went to the House of Representatives, where, at a joint session of Congress, he took the oath as president from William Cranch, chief judge of the federal court for the District of Columbia, and the man who had sworn in President Tyler. The cabinet officers, as was customary when a new president took over, submitted their resignations, expecting Fillmore to refuse, allowing them to continue in office. Fillmore had been marginalized by the cabinet members, and he accepted the resignations, though he asked them to stay on for a month, which most refused to do. Fillmore is the only president who succeeded by death or resignation not to retain, at least initially, his predecessor's cabinet. He was already in discussions with Whig leaders, and on July 20 began to send new nominations to the Senate, with the Fillmore Cabinet to be led by Webster as Secretary of State. Webster had outraged his Massachusetts constituents by supporting Clay's bill, and with his Senate term to expire in 1851, had no political future in his home state. Fillmore appointed his old law partner, Nathan Hall, as Postmaster General, a cabinet position that controlled many patronage appointments.[87] The new department heads were mostly supporters of the Compromise, as was Fillmore.[88]

The brief pause from politics out of national grief at Taylor's death did not abate the crisis. Texas had attempted to assert its authority in New Mexico territory, and the state's governor, Peter H. Bell, had sent belligerent letters to President Taylor.[89] Fillmore received another one after becoming president. He reinforced federal troops in the area and warned Bell to keep the peace.[88]

By July 31, Clay's bill was effectively dead, as all the significant provisions other than the organization of Utah Territory had been deleted by amendment. As one wag put it, the "Mormons" were the only remaining passengers on the Omnibus.[90] Illinois senator Stephen A. Douglas then stepped to the fore, with Clay's agreement, proposing to break the Omnibus into individual bills that could be passed piecemeal.[90] Fillmore endorsed this strategy, with the Omnibus to become (as it proved) five bills.[2]

Fillmore sent a special message to Congress on August 6, 1850, disclosing the letter from Governor Bell and his reply, warning that armed Texans would be viewed as intruders, and urging Congress to defuse sectional tensions by passing the Compromise. Without the presence of the Great Triumvirate of John C. Calhoun, Webster, and Clay, who had long dominated the Senate;[lower-alpha 10] Douglas and others were able to lead that body towards the administration-backed package of bills. Each bill passed the Senate with the support of the section that wanted it, plus a few members who were determined to see all the bills passed. The battle then moved to the House, which had a Northern majority because of population. Most contentious was the Fugitive Slave Bill, whose provisions were anathema to abolitionists. Fillmore applied pressure to get Northern Whigs, including New Yorkers, to abstain rather than oppose the bill. Through the legislative process, various changes were made, including the setting of a boundary between New Mexico Territory and Texas—the state would be given a payment to settle any claims. California was admitted as a free state, the District slave trade was ended, and the final status of slavery in New Mexico and Utah would be settled later. Fillmore signed the bills as they reached his desk, holding the Fugitive Slave Bill for two days until he received a favorable opinion as to its constitutionality from the new Attorney General, John J. Crittenden. Although some Northerners were unhappy at the Fugitive Slave Act, relief was widespread, as it was hoped this would settle the slavery question.[91][92]

Domestic affairs

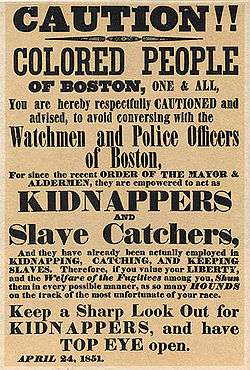

The Fugitive Slave Act remained contentious after its enactment: Southerners complained bitterly about any leniency in its application, but its enforcement was highly offensive to many Northerners. Abolitionists recited the inequities of the law: anyone aiding an escaped slave was punished severely, and it granted no due process to the escapee who could not testify before a magistrate. The law also permitted higher payment to the hearing magistrate for deciding the escapee was a slave rather than free. Nevertheless, Fillmore believed himself bound by his oath as president and by the bargain made in the Compromise to enforce the Fugitive Slave Act. He did so even though some prosecutions or attempts to return slaves ended badly for the government, with acquittals or the slave taken from federal custody and freed by a Boston mob. Such cases were widely publicized North and South, and inflamed passions in both places, undermining the good feeling that had followed the Compromise.[93]

In August 1850, the social reformer Dorothea Dix wrote to Fillmore, urging support of her proposal in Congress for land grants to finance asylums for the impoverished mentally ill. Though her proposal did not pass, they became friends, met in person and corresponded, which continued well after Fillmore's presidency.[94] In September of that year, Fillmore appointed The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints leader Brigham Young as the first governor of Utah Territory.[95] In gratitude, Young named the first territorial capital "Fillmore" and the surrounding county "Millard".[96]

A longtime supporter of national infrastructure development, Fillmore signed bills to subsidize the Illinois Central railroad from Chicago to Mobile, and for a canal at Sault Ste. Marie. The 1851 completion of the Erie Railroad in New York prompted Fillmore and his cabinet to ride the first train from New York City to the shores of Lake Erie, in company with many other politicians and dignitaries. Fillmore made many speeches along the way from the train's rear platform, urging acceptance of the Compromise, and afterwards went on a tour of New England with his Southern cabinet members. Although Fillmore urged Congress to authorize a transcontinental railroad, it did not do so until a decade later.[97]

Fillmore appointed one justice to the Supreme Court of the United States and made four appointments to United States District Courts, including that of his law partner and cabinet officer, Nathan Hall, to the federal district court in Buffalo.[98] When Supreme Court Justice Levi Woodbury died in September 1851 with the Senate not in session, Fillmore made a recess appointment of Benjamin Robbins Curtis to the high court. In December, with Congress convened, Fillmore formally nominated Curtis, who was confirmed. In 1857, Justice Curtis dissented from the Court's decision in the slavery case of Dred Scott v. Sandford, and resigned as a matter of principle.[99]

Justice John McKinley's death in 1852 led to repeated, fruitless attempts by the president to fill the vacancy. The Senate took no action on the nomination of New Orleans attorney Edward A. Bradford. Fillmore's second choice, George Edmund Badger, asked that his name be withdrawn. Senator-elect Judah P. Benjamin declined to serve. The nomination of William C. Micou, a New Orleans lawyer recommended by Benjamin, was not acted on by the Senate. The vacancy was finally filled after Fillmore's term, when President Franklin Pierce nominated John Archibald Campbell, who was confirmed by the Senate.[100]

Foreign relations

Fillmore oversaw two highly competent Secretaries of State, Daniel Webster, and after the New Englander's 1852 death, Edward Everett, looking over their shoulders and making all major decisions.[101] The president was particularly active in Asia and the Pacific, especially with regard to Japan, which at the time still prohibited nearly all foreign contact. American merchants and shipowners wanted Japan "opened up" for trade. This would not only allow commerce, but would also permit American ships to call there for food and water, and in emergencies without being punished. They were concerned that American sailors cast away on the Japanese coast were imprisoned as criminals.[102] Fillmore and Webster dispatched Commodore Matthew C. Perry on an expedition to open Japan to relations with the outside world. Perry and his ships reached Japan in July 1853, four months after the end of Fillmore's term.[102]

Fillmore was a staunch opponent of European influence in Hawaii. France, under Napoleon III, sought to annex Hawaii, but backed down after Fillmore issued a strongly worded message warning that "the United States would not stand for any such action."[102] Taylor had pressed Portugal for payment of American claims dating as far back as the War of 1812, and had refused offers of arbitration; Fillmore gained a favorable settlement.[103]

Fillmore had difficulties regarding Cuba; many Southerners hoped to see the island part of the U.S. as slave territory: Cuba was a colony of Spain where slavery was practiced.[102] Venezuelan adventurer Narciso López recruited Americans for three filibustering expeditions to Cuba, in the hope of overthrowing Spanish rule there. After the second attempt in 1850, López and some of his followers were indicted for breach of the Neutrality Act but were quickly acquitted by friendly Southern juries.[102] The final López expedition ended with his execution by the Spanish, who put several Americans before the firing squad, including the nephew of Attorney General Crittenden. This resulted in riots against the Spanish in New Orleans, causing their consul to flee. The historian Elbert B. Smith, who wrote of the Taylor and Fillmore presidencies, suggested that Fillmore could have had war against Spain had he wanted it. Instead, Fillmore, Webster and the Spanish worked out a series of face-saving measures that settled the crisis without armed conflict. Many Southerners, including Whigs, supported the filibusters, and Fillmore's response helped divide his party as the 1852 election approached.[104]

A much-publicized event of Fillmore's presidency was the arrival in late 1851 of Lajos Kossuth, the exiled leader of a failed Hungarian revolution against Austria. Kossuth wanted the U.S. to recognize Hungary's independence. Many Americans were sympathetic to the Hungarian rebels, especially recent German immigrants, who were now coming to the U.S. in large numbers and had become a major political force. Kossuth was feted by Congress, and Fillmore allowed a White House meeting after receiving word that Kossuth would not try to politicize it. In spite of his promise, Kossuth made a speech promoting his cause. The American enthusiasm for Kossuth petered out, and he departed for Europe; Fillmore refused to change American policy, remaining neutral.[105]

| The Fillmore Cabinet | ||

|---|---|---|

| Office | Name | Term |

| President | Millard Fillmore | 1850–1853 |

| Vice President | None | 1850–1853 |

| Secretary of State | Daniel Webster | 1850–1852 |

| Edward Everett | 1852–1853 | |

| Secretary of the Treasury | Thomas Corwin | 1850–1853 |

| Secretary of War | Charles Magill Conrad | 1850–1853 |

| Attorney General | Reverdy Johnson | 1850 |

| John J. Crittenden | 1850–1853 | |

| Postmaster General | Nathan K. Hall | 1850–1852 |

| Samuel Dickinson Hubbard | 1852–1853 | |

| Secretary of the Navy | William Alexander Graham | 1850–1852 |

| John P. Kennedy | 1852–1853 | |

| Secretary of the Interior | Thomas McKean Thompson McKennan | 1850 |

| Alexander Hugh Holmes Stuart | 1850–1853 | |

Election of 1852 and completion of term

As the election of 1852 approached, Fillmore remained undecided whether to run for a full term as president. Secretary Webster had long coveted the presidency and, though past seventy, planned a final attempt to gain the White House. Fillmore, sympathetic to the ambitions of his longtime friend, issued a letter in late 1851 stating that he did not seek a full term, but he was reluctant to rule it out, fearing the party would be captured by the Sewardites. Thus, approaching the national convention in Baltimore, to be held in June 1852, the major candidates were Fillmore, Webster and General Scott. Weed and Seward backed Scott; in late May, the Democrats nominated former New Hampshire senator Franklin Pierce, who had been out of national politics for nearly a decade before 1852 but whose profile had risen as a result of his military service in the Mexican War. His nomination as a northerner sympathetic to the southern view on slavery united the Democrats and meant the Whig candidate would face an uphill battle to gain the presidency.[106]

By then, Fillmore was unpopular with northern Whigs for signing and enforcing the Fugitive Slave Act but had considerable support from the South, where he was seen as the only candidate capable of uniting the party. Once the convention passed a party platform endorsing the Compromise as a final settlement of the slavery question, Fillmore was willing to withdraw. He found that many of his supporters could not accept Webster and his action would nominate Scott. The convention deadlocked, and this persisted through Saturday, June 19, when a total of 46 ballots had been taken; delegates adjourned until Monday. Party leaders proposed a deal to both Fillmore and Webster: if the secretary could increase his vote total over the next several ballots, enough Fillmore supporters would go along to put him over the top; if he could not, Webster would withdraw in favor of Fillmore. The president quickly agreed, but Webster did not do so until Monday morning. On the 48th ballot, Webster delegates began to defect to Scott, and the general gained the nomination on the 53rd ballot. Webster was far more unhappy at the outcome than was Fillmore, who refused the secretary's resignation. Bereft of the votes of much of the South, and also of Northerners who depended on peaceful intersectional trade, Scott was easily beaten by Pierce in November. Smith suggested that the Whigs might have done much better with Fillmore.[107]

The final months of Fillmore's term were uneventful. Webster died in October 1852, but during his final illness, Fillmore effectively acted as his own Secretary of State without incident, and Everett stepped competently into Webster's shoes. Fillmore intended to lecture Congress on the slavery question in his final annual message in December, but was talked out of it by his cabinet, and he contented himself with pointing out the prosperity of the nation and expressing gratitude for the opportunity to serve it. There was little discussion of slavery during the lame duck session of Congress, and Fillmore left office on March 4, 1853, succeeded by Pierce.[108]

Post-presidency

Tragedy and political turmoil (1853–1855)

Fillmore was the first president to return to private life without independent wealth or possession of a landed estate. With no pension to anticipate, he needed to earn a living and felt it should be in a way that would uphold the dignity of his former office. His friend Judge Hall assured him it would be proper for him to practice law in the higher courts of New York, and Fillmore so intended.[109] The Fillmores had planned a tour of the South after leaving the White House, but Abigail caught a cold at President Pierce's inauguration, developed pneumonia, and died in Washington on March 30, 1853. A saddened Fillmore returned to Buffalo for the burial.[110] The fact that he was in mourning limited his social activities, and he made ends meet on the income from his investments.[111] He was bereaved again on July 26, 1854, when his only daughter, Mary, died of cholera.[112]

The former president ended his seclusion in early 1854, as debate over Senator Douglas's Kansas–Nebraska Bill embroiled the nation. This would open the northern portion of the Louisiana Purchase to settlement, including slavery, and would end the northern limit on slavery under the Missouri Compromise of 1820. Fillmore retained many supporters and planned an ostensibly non-political national tour, while privately rallying disaffected Whig politicians to preserve the Union, and back him in a run for president. Fillmore made public appearances opening railroads and visiting the grave of Senator Clay but met with politicians out of the public eye during the late winter and spring of 1854.[113]

Such a comeback could not be under the auspices of the Whig Party, with its remnants divided by the Kansas–Nebraska legislation (which passed with the support of Pierce). Many northern foes of slavery, such as Seward, gravitated towards a new party, the Republicans, but Fillmore saw no home for himself there. In the early 1850s there was considerable hostility towards immigrants, especially Catholics, who had recently arrived in the United States in large numbers; several nativist organizations, including the Order of the Star Spangled Banner, sprang up in reaction. By 1854, the Order had morphed into the American Party, which became known as the Know Nothings. (In its early days, members were sworn to keep its internal deliberations private, and if asked, were to say they knew nothing about them.)[114] Many from Fillmore's "National Whig" faction had joined the Know Nothings by 1854 and influenced the organization to take up causes besides nativism.[115] Fillmore was encouraged by the success of the Know Nothings in the 1854 midterm elections, in which they won in several Northeastern states and showed strength in the South. On January 1, 1855, he sent a letter for publication, warning against immigrant influence in American elections, and soon thereafter joined the Order of the Star Spangled Banner.[116]

Later that year, Fillmore went abroad, stating publicly that as he lacked office, he might as well travel. The trip was at the advice of political friends, who felt that by touring, he would avoid involvement in the contentious issues of the day. He spent over a year, from March 1855 to June 1856, in Europe and the Middle East. Queen Victoria is said to have pronounced the ex-president the handsomest man she had ever seen, and his coincidental appearance with Van Buren in the gallery of the House of Commons triggered a comment from MP John Bright.[117] Fillmore was offered an honorary Doctor of Civil Law (D.C.L.) degree by the University of Oxford; he declined, explaining that he had neither the "literary nor scientific attainment" to justify the degree.[118] He is also quoted as saying that he "lacked the benefit of a classical education" and could not, therefore, understand the Latin text of the diploma, adding that he believed "no man should accept a degree he cannot read."[119] Alternatively, Fillmore may have refused the degree to escape the heckling and taunting which Oxford students typically imposed upon the recipients of such honors.[120][lower-alpha 11]

Dorothea Dix had preceded him to Europe and was lobbying to improve conditions for the mentally ill. They continued to correspond and met several times.[122] In Rome, Fillmore had an audience with Pope Pius IX. He carefully weighed the political pros and cons of meeting with Pius; he nearly withdrew from the meeting when told he would have to kneel and kiss the pope's hand. To avoid this, Pius remained seated throughout the meeting.[123][124]

1856 campaign

Fillmore's allies were in full control of the American Party, and they arranged for him to get its presidential nomination while he was in Europe. The Know Nothing convention chose Andrew Jackson Donelson of Kentucky to be Fillmore's running mate; he was the nephew by marriage and onetime ward of President Jackson. Fillmore made a celebrated return in June 1856, speaking at a series of welcomes, which began with his arrival at a huge reception in New York City and continued across the state to Buffalo. These addresses were portrayed as expressions of thanks for his reception, rather than as campaign speeches, which might be considered illicit office-seeking if made by a presidential hopeful. Fillmore warned that electing the Republican candidate, former California senator John C. Frémont, who had no support in the South, would divide the Union and lead to civil war. Both Fillmore and the Democratic candidate, former Pennsylvania senator James Buchanan, agreed that slavery was principally a matter for state and not federal government. Fillmore rarely spoke about the immigration question, and focused on the sectional divide, urging preservation of the Union.[125][126]

Once Fillmore was back home in Buffalo, he had no excuse to make speeches, and his campaign stagnated through the summer and fall of 1856. Political fixers who had been Whigs, such as Weed, tended to join the Republican Party, and the Know Nothings lacked experience at selling anything but nativism. Accordingly, Fillmore's pro-Union stance mostly went unheard. Although the South was friendly towards Fillmore, many there feared a Frémont victory would lead to secession, and some sympathetic to Fillmore moved into the Buchanan camp lest the anti-Frémont vote be split, which might elect the Republican.[127] Scarry suggested that the events of 1856, including the conflict in Kansas Territory and the caning of Charles Sumner on the floor of the Senate, polarized the nation, making Fillmore's moderate stance obsolete.[128]

On Election Day, Buchanan won with 1,836,072 votes (45.3%) and 174 electoral votes to Frémont's 1,342,345 votes (33.1%) and 114 electoral votes. Fillmore and Donelson finished third, winning 873,053 votes (21.6%) and carrying the state of Maryland and its 8 electoral votes.[lower-alpha 12] The American Party ticket narrowly lost in several southern states, and a change of fewer than 8,000 votes in Louisiana, Kentucky, and Tennessee would have thrown the election to the House of Representatives, where the sectional divide would have made the outcome uncertain.[130]

Historian Allan Nevins wrote that Fillmore was not a Know Nothing or a nativist. He was out of the country when the nomination came and had not been consulted about running. Furthermore, "By no spoken or written word had he indicated a subscription to American tenets."[131][132] He sought national unity and felt the American Party was the "only hope of forming a truly national party, which shall ignore this constant and distracting agitation of slavery."[133]

Remarriage, later life, and death

.jpg)

Fillmore considered his political career to be at an end with his defeat in 1856. He again felt inhibited from returning to the practice of law. However, his financial worries were removed on February 10, 1858, when he married Caroline McIntosh, a well-to-do widow. Their combined wealth allowed them to purchase a large house on Niagara Square in Buffalo, where they lived for the remainder of his life.[134] There, the Fillmores devoted themselves to entertaining and philanthropy; according to historian Smith, "they generously supported almost every conceivable cause".[135] Among these were the Buffalo Historical Society and the Buffalo General Hospital, which he helped found.[136]

In the election of 1860, Fillmore voted for Senator Douglas, the nominee of the northern Democrats. After the vote, in which the Republican candidate, former Illinois representative Abraham Lincoln, was elected, many sought out Fillmore's views, but he refused to take any part in the secession crisis that followed, feeling that he lacked influence.[137] He decried Buchanan's inaction as states left the Union, writing that while the federal government could not coerce a state, those advocating secession should simply be regarded as traitors. When Lincoln came to Buffalo en route to his inauguration, Fillmore led the committee selected to receive the president-elect, hosted him at his mansion, and took him to church. Once war came, Fillmore supported Lincoln in his efforts to preserve the Union.[138] He commanded the Union Continentals, a corps of home guards of males over the age of 45 from the upstate New York area. The Continentals trained to defend the Buffalo area in the event of a Confederate attack. They performed military drill and ceremonial functions at parades, funerals, and other events. The Union Continentals guarded Lincoln's funeral train in Buffalo. They continued operations after the war, and Fillmore remained active with them almost until his death.[139][140]

Despite Fillmore's zeal in the war effort, he gave a speech in early 1864 calling for magnanimity towards the South at war's end and counting its heavy cost, both financial and in blood. The Lincoln administration saw this as an attack on it that could not be tolerated in an election year, and Fillmore was criticized in many newspapers, called a Copperhead and even a traitor. This led to lasting ill-feeling against Fillmore in many circles.[141] In the 1864 presidential election Fillmore supported Democratic candidate George B. McClellan for the presidency, believing that the Democratic Party's plan for immediate cessation of fighting and allowing the seceded states to return with slavery intact was the best possibility for restoring the Union.[142]

After Lincoln's assassination in April 1865, black ink was thrown on Fillmore's house because it was not draped in mourning like others; he was apparently out of town at the time and put black drapes in the windows once he returned. Although he retained his position as Buffalo's leading citizen, and was among those selected to escort the body when Lincoln's funeral train passed through Buffalo, there was still anger towards him for his wartime positions.[143] Fillmore supported President Andrew Johnson's Reconstruction policies, feeling that the nation needed to be reconciled as quickly as possible.[144] He devoted most of his time to civic activities. He aided Buffalo in becoming the third American city to have a permanent art gallery, with the Buffalo Fine Arts Academy.[145]

Fillmore stayed in good health almost to the end, but suffered a stroke in February 1874, and died after a second one on March 8 at the age of 74. Two days later, he was buried at Forest Lawn Cemetery in Buffalo after a funeral procession including hundreds of notables;[146] the U.S. Senate sent three of its members to honor its former president, including Lincoln's first vice president, Maine's Hannibal Hamlin.[147]

Legacy and historical view

According to biographer Scarry: "No president of the United States ... has suffered as much ridicule as Millard Fillmore".[148] He ascribed much of the abuse to a tendency to denigrate the presidents who served in the years just prior to the Civil War as lacking in leadership. For example, later president Harry S. Truman "characterized Fillmore as a weak, trivial thumb-twaddler who would do nothing to offend anyone", and as responsible in part for the war.[149] Anna Prior, writing in The Wall Street Journal in 2010, said that Fillmore's very name connotes mediocrity.[150] Another Fillmore biographer, Finkelman, commented, "on the central issues of the age his vision was myopic and his legacy is worse ... in the end, Fillmore was always on the wrong side of the great moral and political issues".[151] Rayback, however, applauded "the warmth and wisdom with which he had defended the Union".[152]

Although Fillmore has become something of a cult figure as America's most forgettable chief executive, Smith found him to be "a conscientious president" who chose to honor his oath of office and enforce the Fugitive Slave Act, rather than govern based on his personal preferences.[153] Steven G. Calabresi and Christopher S. Yoo, in their study of presidential power, deemed Fillmore "a faithful executor of the laws of the United States—for good and for ill".[154] But, according to Smith, the enforcement of the act has given Fillmore an undeserved pro-southern reputation. Fillmore's place in history has also suffered because "even those who give him high marks for his support of the compromise have done so almost grudgingly, probably because of his Know-Nothing candidacy in 1856".[155] Smith argued that Fillmore's association with the Know Nothings looks far worse in retrospect than it did at the time and that the former president was not motivated by nativism in his candidacy.[156]

Benson Lee Grayson suggested that the Fillmore administration's ability to avoid potential problems is too often overlooked. Fillmore's constant attention to Mexico avoided a resumption of the Mexican–American War and laid the groundwork for the Gadsden Treaty during Pierce's presidency.[157] Meanwhile, the Fillmore administration resolved a controversy with Portugal left over from the Taylor administration,[158] smoothed over a disagreement with Peru over guano islands, and peacefully resolved disputes with Britain, France, and Spain over Cuba. All of these crises were resolved without the United States going to war or losing face.[159] Grayson also applauded Fillmore's firm stand against Texas' ambitions in New Mexico during the 1850 crisis.[160] Fred I. Greenstein and Dale Anderson praised Fillmore for his resoluteness in his early months in office, noting that Fillmore "is typically described as stolid, bland, and conventional, but such terms underestimate the forcefulness evinced by his handling of the Texas–New Mexico border crisis, his decision to replace Taylor's entire cabinet, and his effectiveness in advancing the Compromise of 1850".[161]

Millard Fillmore, with his wife Abigail, established the first White House library.[162] There are a number of remembrances of Millard Fillmore; his East Aurora house still stands, and sites honor him at his birthplace and boyhood home, where a replica log cabin was dedicated in 1963 by the Millard Fillmore Memorial Association.[163] A statue of Fillmore stands outside Buffalo City Hall.[164] At the university he helped found, now University at Buffalo, Millard Fillmore Academic Center and Millard Fillmore College bear his name.[165][166] On February 18, 2010, the United States Mint released the thirteenth coin in the Presidential $1 Coin Program, bearing Fillmore's likeness.[150][167]

According to the assessment of Fillmore by the Miller Center of Public Affairs at the University of Virginia:

Any assessment of a President who served a century and a half ago must be refracted through a consideration of the interesting times in which he lived. Fillmore's political career encompassed the tortuous course toward the two-party system that we know today. The Whigs were not cohesive enough to survive the slavery imbroglio, while parties like the Anti-Masonics and Know-Nothings were too extremist. When, as President, Fillmore sided with proslavery elements in ordering enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Law, he all but guaranteed that he would be the last Whig President. The first modern two-party system of Whigs and Democrats had succeeded only in dividing the nation in two by the 1850s, and seven years later, the election of the first Republican President, Abraham Lincoln, would guarantee civil war.[168]

Statue by Bryant Baker at Buffalo City Hall, Buffalo, New York, 1930

Statue by Bryant Baker at Buffalo City Hall, Buffalo, New York, 1930 Fillmore's East Aurora house was moved off Main Street.

Fillmore's East Aurora house was moved off Main Street. The house is designated a National Historic Landmark.

The house is designated a National Historic Landmark. The DAR placed this plaque on the house in 1931.

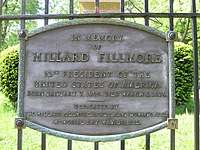

The DAR placed this plaque on the house in 1931. A memorial to Fillmore on the gate surrounding his plot in Buffalo

A memorial to Fillmore on the gate surrounding his plot in Buffalo Detail of the Fillmore obelisk in Buffalo

Detail of the Fillmore obelisk in Buffalo

See also

- List of Presidents of the United States, sortable by previous experience

- U.S. Presidents on U.S. postage stamps

Notes

- Fillmore was Vice President under President Zachary Taylor and became President upon Taylor's death on July 9, 1850. Prior to the adoption of the Twenty-Fifth Amendment in 1967, a vacancy in the office of Vice President was not filled until the next ensuing election and inauguration.

- The original log cabin was demolished in 1852, but in 1965 the Millard Fillmore Memorial Association, using materials from a similar cabin, constructed a replica, which is located in Fillmore Glen State Park in Moravia.[1]

- Later, Nathaniel, the first father of a president to visit his son at the White House, alluded to his family's onetime poverty when he told a questioner how to raise a son to be president: "Cradle him in a sap trough".[7][8]

- Fillmore's uncle Calvin Fillmore served in the New York State Assembly;[27] another uncle, Simeon Fillmore, served as town supervisor of Clarence, New York.[28]

- South Carolina did not yet use the popular vote for choosing electors, with the legislature electing them instead.

- Until 1913, senators were elected by state legislatures, not by the people.

- The modern-day states of New Mexico and Arizona, less the Gadsden Purchase

- The constitution designates the vice president as the Senate's presiding officer.

- The term derives from the transportation vehicle, as the bill carries all the related proposals as 'passengers'.

- Calhoun was dead, Webster was Secretary of State, and Clay was absent, recovering from his exertions on behalf of the bill at Newport, Rhode Island.

- In fact, Fillmore had been awarded an honorary LL.D. from Geneva College in 1850; he accepted, even though its text was in Latin.[121]

- Fillmore thus became the first former president to receive electoral votes, a distinction which later also included Grover Cleveland (1892) and Theodore Roosevelt (1912).[129]

References

- "Presidential Places: Millard Fillmore". American Presidents: Life Portraits. C-SPAN. Archived from the original on February 24, 2015. Retrieved December 20, 2016.

- American National Biography.

- Bahles, Gerald (2010). "Millard Fillmore: Life Before the Presidency". American President: Miller Center of Public Affairs. Archived from the original on October 18, 2016. Retrieved October 19, 2016.

- Bassett, Mary Cooley; Johnston, Sarah Hall (1914). Lineage Book, National Society of the Daughters of the American Revolution. 39. Harrisburg, PA: Telegraph Printing Company. p. 111. Archived from the original on February 19, 2017. Retrieved February 18, 2017.

- Rayback, 191–197.

- Storke, Elliot G. (1879). History of Cayuga County. Syracuse, NY: D. Mason & Co. p. 513. ISBN 9785878134804. Archived from the original on February 19, 2017. Retrieved February 18, 2017.

- Snyder, p. 50.

- Fillmore, Millard; Severance, Frank H. (1907). Millard Fillmore Papers. 2. Buffalo, NY: Buffalo Historical Society. pp. 151, 510. ISBN 9781623765767. Archived from the original on November 17, 2016. Retrieved October 4, 2016.

- Smith, Henry Perry (1884). History of the City of Buffalo and Erie County. I. Syracuse, NY: D. Mason & Co. p. 197.

- Scarry, 18.

- Doty, Lockwood Lyon (1876). A History of Livingston County, New York. Geneseo, New York: Edward L. Doty. pp. 673–676. OCLC 14246825. Archived from the original on August 21, 2008. Retrieved November 16, 2019.

- Scarry, 19.

- Scarry, 20.

- Rayback, 224–258.

- Scarry, 22.

- Scarry, 23.

- Scarry, 24.

- Scarry, 25.

- Rayback, 258–308.

- Finkelman, p. 5.

- Dayer, Donald H.; Utts, Harold L.; Utts, Janet R. (2000). Town of Aurora: 1818–1930. Mount Pleasant, SC: Arcadia Publishing. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-7385-0445-2.

- Scarry, 26.

- Scarry, 528–34.

- Finkelman, pp. 5–6.

- Scarry, 128–134.

- TownRecords. A-1. Bennington, VT: Bennington Town Clerk. 1767. pp. 39, 50, 73. Archived from the original on February 19, 2017. Retrieved February 18, 2017.

- Johnson, Crisfield (1876). Centennial History of Erie County, New York. Buffalo, NY: Matthews & Warren. pp. 355–356. Archived from the original on February 18, 2017. Retrieved February 18, 2017.

- Centennial History of Erie County, New York.

- Finkelman, pp. 12–13.

- Scarry, 42.

- Smith, p. 45.

- Rayback, 314, 750–810.

- Skinner, Roger Sherman (1830). The New-York State Register for 1830. New York: Clayton & Van Norden. p. 361. Archived from the original on November 17, 2016. Retrieved June 27, 2015.

- Millard Fillmore Papers.

- Scarry, 936–940, 993–999.

- Rayback, 878–905.

- Finkelman, p. 13.

- Rayback, 1261.

- Scarry, 999.

- Finkelman, p. 14.

- Scarry, 1079.

- Rayback, 1495–1508.

- Rayback, 1556–1679.

- Scarry, 1326–1331.

- Scarry, 1356–1361.

- Scarry, 1891.

- Rayback, 1950–1957.

- Rayback, 1957–2186.

- Scarry, 1729–1776.

- Scarry, 1766.

- Scarry, 1776–1820.

- Rayback, 2417.

- Rayback, 2425–2471.

- Rayback, 2471–2486.

- Rayback, 2486–2536.

- Rayback, 2536–2562.

- Finkelman, p. 24.

- Finkelman, pp. 23–24.

- Finkelman, pp. 35, 152.

- Rayback, 2620.

- Rayback, 2735–2763.

- Finkelman, p. 25.

- Rayback, 2769–2799.

- Finkelman, pp. 43–45.

- Rayback, 2902–2955.

- Rayback, 2981–2994.

- Rayback, 3001–3008.

- Finkelman, pp. 47–49.

- Snyder, p. 37.

- Scarry, 3138–3150.

- Finkelman, p. 53.

- Scarry, 3188–3245.

- Finkelman, p. 51.

- Scarry, 3245–3258.

- Rayback, 3090.

- Scarry, 3283.

- Finkelman, pp. 51–52.

- Rayback, 3101–3307.

- Smith, pp. 160–162.

- Rayback, 3307–3367.

- Smith, pp. 93–94.

- Rayback, 3367–3399.

- Scarry, 3445–3467.

- Smith, pp. 138–139, 163–165.

- Finkelman, p. 1.

- Snyder, p. 43.

- Finkelman, pp. 72–77.

- Greenstein & Anderson, p. 48.

- Smith, pp. 152–157.

- Smith, pp. 158–160.

- Scarry, 4025–4102.

- Finkelman, pp. 82–85.

- Smith, pp. 208–13.

- Snyder, pp. 80–82.

- "The American Franchise". American President, An Online Reference Resource. Miller Center of Public Affairs, University of Virginia. Archived from the original on April 21, 2008. Retrieved March 13, 2008.

- Winder, Michael Kent (2007). Presidents and Prophets: The Story of America's Presidents and the LDS Church. American Fork, UT: Covenant Communications. ISBN 978-1-59811-452-2.

- Smith, pp. 199–200.

- "Biographical Dictionary of the Federal Judiciary". Washington, DC: Federal Judicial Center. Archived from the original on July 30, 2016. Retrieved March 4, 2012. searches run from page, "select research categories" then check "court type" and "nominating president", then select U.S. District Courts (or U.S. Circuit Courts) and also Millard Fillmore.

- Smith, pp. 218, 247.

- "Supreme Court Nominations, 1789–Present". Senate.gov. U.S. Senate. Archived from the original on December 26, 2017. Retrieved September 8, 2014.

- Smith, p. 233.

- Bahles, Gerald (2010). "Millard Fillmore: Foreign Affairs". American President: Miller Center of Public Affairs. Archived from the original on November 5, 2013. Retrieved October 19, 2016.

- Smith, pp. 72–73.

- Smith, p. 228.

- Smith, pp. 230–232.

- Smith, pp. 238–244.

- Smith, pp. 244–247.

- Smith, pp. 247–249.

- Rayback, 5726–5745.

- Rayback, 5858–5865.

- Rayback, 6025–6031.

- Millard Fillmore, author, Frank H. Severance, editor, Millard Fillmore Papers Archived November 17, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, Volume X, 1907, p. 25.

- Rayback, 6038–6057.

- Rayback, 5900–5966.

- Rayback, 5952–5959.

- Smith, pp. 252–253.

- Rayback, 6191–6234.

- "Millard Fillmore". Internet Public Library. Archived from the original on May 28, 2007. Retrieved December 20, 2013.

- "Millard Fillmore". EBSCO Industries, Inc. Archived from the original on January 25, 2016. Retrieved December 21, 2013.

- Scarry, Robert J. (2001). Millard Fillmore. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, Inc. p. 270. ISBN 978-0-7864-0869-6. Archived from the original on November 17, 2016. Retrieved April 28, 2016.

- "Honorary Degree Recipients, 1827–1913" (PDF). Hobart and William Smith Colleges Library. Geneva, NY: Hobart and William Smith Colleges. 2013. p. 39. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 5, 2016.

- Snyder, pp. 217–218.

- Rayback, 6248.

- Finkelman, p. 132.

- Scarry, 6650–6699.

- Rayback, 6326–6411.

- Rayback, 6398–6458.

- Scarry, 6918.

- "Presidential Elections, 1789–2016". infoplease.com. Archived from the original on February 8, 2017. Retrieved January 11, 2017.

- Rayback, 6458–6473.

- Nevins, Allan (1947). Ordeal of the Union: A House Dividing 1852–1857. New York City: Charles Scribner’s Sons. p. 467.

- Gienapp, William E. (1987). The Origins of the Republican Party, 1852–1856. p. 260n.

- Tyler Anbinder. "Fillmore, Millard" American National Biography Online (2000)

- Rayback, 6476–6518.

- Smith, pp. 254–255.

- "Hospital History". Kaleida Health. Kaleida Health. Archived from the original on December 2, 2016. Retrieved December 31, 2016.

- Scarry, 7285–7297.

- Rayback, 6578–6600.

- Proceedings, Volumes 23–37. Buffalo Historical Society. 1885. p. 72. Archived from the original on April 7, 2015. Retrieved June 27, 2015.

- Smith, pp. 264–265.

- Rayback, 6667–6706.

- Neil A. Hamilton, Presidents: A Biographical Dictionary Archived November 17, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, 2010, p. 111.

- Rayback, 6706.

- Finkelman, p. 154.

- Rayback, 6783–6790.

- Rayback, 6930–6946.

- Scarry, 8118.

- Scarry, 8151.

- Scarry, 8157–8161.

- Anna Prior (February 18, 2010). "No Joke: Buffalo and Moravia Duke It Out Over Millard Fillmore". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on December 24, 2013. Retrieved December 1, 2016.

- Finkelman, p. 137.

- Rayback, 6953.

- Smith, pp. 257, 260.

- Calabresi & Yoo, p. 151.