Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (February 27, 1807 – March 24, 1882) was an American poet and educator whose works include "Paul Revere's Ride", The Song of Hiawatha, and Evangeline. He was also the first American to translate Dante Alighieri's Divine Comedy and was one of the Fireside Poets from New England.

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow | |

|---|---|

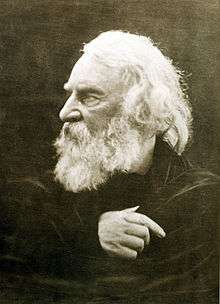

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow photographed by Julia Margaret Cameron in 1868 | |

| Born | February 27, 1807 Portland, Maine, U.S. |

| Died | March 24, 1882 (aged 75) Cambridge, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Occupation | Poet Professor |

| Alma mater | Bowdoin College |

| Spouses | Mary Storer Potter Frances Elizabeth Appleton |

| Children | Charles Appleton Longfellow Ernest Wadsworth Longfellow Fanny Longfellow Alice Mary Longfellow Edith Longfellow Anne Allegra Longfellow |

| Signature | |

Longfellow was born in Portland, Maine, which was then still part of Massachusetts. He studied at Bowdoin College and became a professor at Bowdoin and later at Harvard College after spending time in Europe. His first major poetry collections were Voices of the Night (1839) and Ballads and Other Poems (1841). He retired from teaching in 1854 to focus on his writing, and he lived the remainder of his life in the Revolutionary War headquarters of George Washington in Cambridge, Massachusetts. His first wife Mary Potter died in 1835 after a miscarriage. His second wife Frances Appleton died in 1861 after sustaining burns when her dress caught fire. After her death, Longfellow had difficulty writing poetry for a time and focused on translating works from foreign languages. He died in 1882.

Longfellow wrote many lyric poems known for their musicality and often presenting stories of mythology and legend. He became the most popular American poet of his day and also had success overseas. He has been criticized by some, however, for imitating European styles and writing specifically for the masses.

Life and work

Early life and education

Longfellow was born on February 27, 1807, to Stephen Longfellow and Zilpah (Wadsworth) Longfellow in Portland, Maine,[1] then a district of Massachusetts.[2] He grew up in what is now known as the Wadsworth–Longfellow House. His father was a lawyer, and his maternal grandfather was Peleg Wadsworth, a general in the American Revolutionary War and a Member of Congress.[3] His mother was descended from Richard Warren, a passenger on the Mayflower.[4] He was named after his mother's brother Henry Wadsworth, a Navy lieutenant who had died three years earlier at the Battle of Tripoli.[5] He was the second of eight children.[6]

Longfellow was descended from English colonists who settled in New England in the early 1600s.[7] They included Mayflower Pilgrims Richard Warren, William Brewster, and John and Priscilla Alden through their daughter Elizabeth Pabodie, the first child born in Plymouth Colony.[8]

Longfellow attended a dame school at the age of three and was enrolled by age six at the private Portland Academy. In his years there, he earned a reputation as being very studious and became fluent in Latin.[9] His mother encouraged his enthusiasm for reading and learning, introducing him to Robinson Crusoe and Don Quixote.[10] He published his first poem in the Portland Gazette on November 17, 1820, a patriotic and historical four-stanza poem called "The Battle of Lovell's Pond".[11] He studied at the Portland Academy until age 14. He spent much of his summers as a child at his grandfather Peleg's farm in Hiram, Maine.

In the fall of 1822, 15 year-old Longfellow enrolled at Bowdoin College in Brunswick, Maine, along with his brother Stephen.[9] His grandfather was a founder of the college[12] and his father was a trustee.[9] There Longfellow met Nathaniel Hawthorne who became his lifelong friend.[13] He boarded with a clergyman for a time before rooming on the third floor[14] in 1823 of what is now known as Winthrop Hall.[15] He joined the Peucinian Society, a group of students with Federalist leanings.[16] In his senior year, Longfellow wrote to his father about his aspirations:

I will not disguise it in the least…. the fact is, I most eagerly aspire after future eminence in literature, my whole soul burns most ardently after it, and every earthly thought centres in it…. I am almost confident in believing, that if I can ever rise in the world it must be by the exercise of my talents in the wide field of literature.[17]

He pursued his literary goals by submitting poetry and prose to various newspapers and magazines, partly due to encouragement from Professor Thomas Cogswell Upham.[18] He published nearly 40 minor poems between January 1824 and his graduation in 1825.[19] About 24 of them were published in the short-lived Boston periodical The United States Literary Gazette.[16] When Longfellow graduated from Bowdoin, he was ranked fourth in the class and had been elected to Phi Beta Kappa.[20] He gave the student commencement address.[18]

European tours and professorships

After graduating in 1825, Longfellow was offered a job as professor of modern languages at his alma mater. An apocryphal story claims that college trustee Benjamin Orr had been impressed by Longfellow's translation of Horace and hired him under the condition that he travel to Europe to study French, Spanish, and Italian.[21]

Whatever the catalyst, Longfellow began his tour of Europe in May 1826 aboard the ship Cadmus.[22] His time abroad lasted three years and cost his father $2,604.24,[23] the equivalent of over $67,000 today.[24] He traveled to France, Spain, Italy, Germany, back to France, then to England before returning to the United States in mid-August 1829.[25] While overseas, he learned French, Italian, Spanish, Portuguese, and German, mostly without formal instruction.[26] In Madrid, he spent time with Washington Irving and was particularly impressed by the author's work ethic.[27] Irving encouraged the young Longfellow to pursue writing.[28] While in Spain, Longfellow was saddened to learn that his favorite sister Elizabeth had died of tuberculosis at the age of 20 that May.[29]

On August 27, 1829, he wrote to the president of Bowdoin that he was turning down the professorship because he considered the $600 salary "disproportionate to the duties required". The trustees raised his salary to $800 with an additional $100 to serve as the college's librarian, a post which required one hour of work per day.[30] During his years teaching at the college, he translated textbooks from French, Italian, and Spanish;[31] his first published book was a translation of the poetry of medieval Spanish poet Jorge Manrique in 1833.[32]

He published the travel book Outre-Mer: A Pilgrimage Beyond the Sea in serial form before a book edition was released in 1835.[31] Shortly after the book's publication, Longfellow attempted to join the literary circle in New York and asked George Pope Morris for an editorial role at one of Morris's publications. He considered moving to New York after New York University proposed offering him a newly created professorship of modern languages, though there would be no salary. The professorship was not created and Longfellow agreed to continue teaching at Bowdoin.[33] It may have been joyless work. He wrote, "I hate the sight of pen, ink, and paper ... I do not believe that I was born for such a lot. I have aimed higher than this".[34]

On September 14, 1831, Longfellow married Mary Storer Potter, a childhood friend from Portland.[35] The couple settled in Brunswick, though the two were not happy there.[36] Longfellow published several nonfiction and fiction prose pieces in 1833 inspired by Irving, including "The Indian Summer" and "The Bald Eagle".[37]

In December 1834, Longfellow received a letter from Josiah Quincy III, president of Harvard College, offering him the Smith Professorship of Modern Languages with the stipulation that he spend a year or so abroad.[38] There, he further studied German as well as Dutch, Danish, Swedish, Finnish, and Icelandic.[39] In October 1835, his wife Mary had a miscarriage during the trip, about six months into her pregnancy.[40] She did not recover and died after several weeks of illness at the age of 22 on November 29, 1835. Longfellow had her body embalmed immediately and placed in a lead coffin inside an oak coffin, which was shipped to Mount Auburn Cemetery near Boston.[41] He was deeply saddened by her death and wrote: "One thought occupies me night and day ... She is dead – She is dead! All day I am weary and sad".[42] Three years later, he was inspired to write the poem "Footsteps of Angels" about her. Several years later, he wrote the poem "Mezzo Cammin," which expressed his personal struggles in his middle years.[43]

Longfellow returned to the United States in 1836 and took up the professorship at Harvard. He was required to live in Cambridge to be close to the campus and, therefore, rented rooms at the Craigie House in the spring of 1837.[44] The home was built in 1759 and was the headquarters of George Washington during the Siege of Boston beginning in July 1775.[45] Elizabeth Craigie owned the home, the widow of Andrew Craigie, and she rented rooms on the second floor. Previous boarders included Jared Sparks, Edward Everett, and Joseph Emerson Worcester.[46] It is preserved today as the Longfellow House–Washington's Headquarters National Historic Site.

Longfellow began publishing his poetry in 1839, including the collection Voices of the Night, his debut book of poetry.[47] The bulk of Voices of the Night was translations, though he also included nine original poems and seven poems that he had written as a teenager.[48] Ballads and Other Poems was published in 1841[49] and included "The Village Blacksmith" and "The Wreck of the Hesperus", which were instantly popular.[50] He became part of the local social scene, creating a group of friends who called themselves the Five of Clubs. Members included Cornelius Conway Felton, George Stillman Hillard, and Charles Sumner; Sumner became Longfellow's closest friend over the next 30 years.[51] Longfellow was well liked as a professor, though he disliked being "constantly a playmate for boys" rather than "stretching out and grappling with men's minds."[52]

Courtship of Frances Appleton

Longfellow met Boston industrialist Nathan Appleton and his family in the town of Thun, Switzerland, including his son Thomas Gold Appleton. There he began courting Appleton's daughter Frances "Fanny" Appleton. The independent-minded Fanny was not interested in marriage, but Longfellow was determined.[53] In July 1839, he wrote to a friend: "Victory hangs doubtful. The lady says she will not! I say she shall! It is not pride, but the madness of passion".[54] His friend George Stillman Hillard encouraged him in the pursuit: "I delight to see you keeping up so stout a heart for the resolve to conquer is half the battle in love as well as war".[55] During the courtship, Longfellow frequently walked from Cambridge to the Appleton home in Beacon Hill in Boston by crossing the Boston Bridge. That bridge was replaced in 1906 by a new bridge which was later renamed the Longfellow Bridge.

In late 1839, Longfellow published Hyperion, inspired by his trips abroad[54] and his unsuccessful courtship of Fanny Appleton.[56] Amidst this, he fell into "periods of neurotic depression with moments of panic" and took a six-month leave of absence from Harvard to attend a health spa in the former Marienberg Benedictine Convent at Boppard in Germany.[56] After returning, he published the play The Spanish Student in 1842, reflecting his memories from his time in Spain in the 1820s.[57]

The small collection Poems on Slavery was published in 1842 as Longfellow's first public support of abolitionism. However, as Longfellow himself wrote, the poems were "so mild that even a Slaveholder might read them without losing his appetite for breakfast".[58] A critic for The Dial agreed, calling it "the thinnest of all Mr. Longfellow's thin books; spirited and polished like its forerunners; but the topic would warrant a deeper tone".[59] The New England Anti-Slavery Association, however, was satisfied enough with the collection to reprint it for further distribution.[60]

On May 10, 1843, after seven years, Longfellow received a letter from Fanny Appleton agreeing to marry him. He was too restless to take a carriage and walked 90 minutes to meet her at her house.[61] They were soon married; Nathan Appleton bought the Craigie House as a wedding present, and Longfellow lived there for the rest of his life.[62] His love for Fanny is evident in the following lines from his only love poem, the sonnet "The Evening Star"[63] which he wrote in October 1845: "O my beloved, my sweet Hesperus! My morning and my evening star of love!" He once attended a ball without her and noted, "The lights seemed dimmer, the music sadder, the flowers fewer, and the women less fair."[64]

He and Fanny had six children: Charles Appleton (1844–1893), Ernest Wadsworth (1845–1921), Fanny (1847–1848), Alice Mary (1850–1928), Edith (1853–1915), and Anne Allegra (1855–1934). Their second-youngest daughter was Edith who married Richard Henry Dana III, son of Richard Henry Dana, Jr. who wrote Two Years Before the Mast.[65] Their daughter Fanny was born on April 7, 1847, and Dr. Nathan Cooley Keep administered ether to the mother as the first obstetric anesthetic in the United States.[66] Longfellow published his epic poem Evangeline for the first time a few months later on November 1, 1847.[66] His literary income was increasing considerably; in 1840, he had made $219 from his work, but 1850 brought him $1,900.[67]

On June 14, 1853, Longfellow held a farewell dinner party at his Cambridge home for his friend Nathaniel Hawthorne, who was preparing to move overseas.[68] In 1854, he retired from Harvard,[69] devoting himself entirely to writing. He was awarded an honorary doctorate of laws from Harvard in 1859.[70]

Death of Frances

Frances was putting locks of her children's hair into an envelope on July 9, 1861[71] and attempting to seal it with hot sealing wax while Longfellow took a nap.[72] Her dress suddenly caught fire, though it is unclear exactly how;[73] burning wax or a lighted candle may have fallen onto it.[74] Longfellow was awakened from his nap and rushed to help her, throwing a rug over her, though it was too small. He stifled the flames with his body, but she was already badly burned.[73] Longfellow's youngest daughter Annie explained the story differently some 50 years later, claiming that there had been no candle or wax but that the fire had started from a self-lighting match that had fallen on the floor.[65] Both accounts state that Frances was taken to her room to recover and a doctor was called. She was in and out of consciousness throughout the night and was administered ether. She died shortly after 10 the next morning, July 10, after requesting a cup of coffee.[75] Longfellow had burned himself while trying to save her, badly enough that he was unable to attend her funeral.[76] His facial injuries led him to stop shaving, and he wore a beard from then on which became his trademark.[75]

Longfellow was devastated by Frances’ death and never fully recovered; he occasionally resorted to laudanum and ether to deal with his grief.[77] He worried that he would go insane, begging "not to be sent to an asylum" and noting that he was "inwardly bleeding to death".[78] He expressed his grief in the sonnet "The Cross of Snow" (1879) which he wrote 18 years later to commemorate her death:[43]

- Such is the cross I wear upon my breast

- These eighteen years, through all the changing scenes

- And seasons, changeless since the day she died.[78]

Later life and death

Longfellow spent several years translating Dante Alighieri's Divine Comedy. To aid him in perfecting the translation and reviewing proofs, he invited friends to meetings every Wednesday starting in 1864.[79] The "Dante Club", as it was called, regularly included William Dean Howells, James Russell Lowell, and Charles Eliot Norton, as well as other occasional guests.[80] The full three-volume translation was published in the spring of 1867, though Longfellow continued to revise it.[81] It went through four printings in its first year.[82] By 1868, Longfellow's annual income was over $48,000.[83] In 1874, Samuel Cutler Ward helped him sell the poem "The Hanging of the Crane" to the New York Ledger for $3,000; it was the highest price ever paid for a poem.[84]

During the 1860s, Longfellow supported abolitionism and especially hoped for reconciliation between the northern and southern states after the American Civil War. His son was injured during the war, and he wrote the poem "Christmas Bells", later the basis of the carol I Heard the Bells on Christmas Day. He wrote in his journal in 1878: "I have only one desire; and that is for harmony, and a frank and honest understanding between North and South".[85] Longfellow accepted an offer from Joshua Chamberlain to speak at his fiftieth reunion at Bowdoin College, despite his aversion to public speaking; he read the poem "Morituri Salutamus" so quietly that few could hear him.[86] The next year, he declined an offer to be nominated for the Board of Overseers at Harvard "for reasons very conclusive to my own mind".[87]

On August 22, 1879, a female admirer traveled to Longfellow's house in Cambridge and, unaware to whom she was speaking, asked him: "Is this the house where Longfellow was born?" He told her that it was not. The visitor then asked if he had died here. "Not yet", he replied.[88] In March 1882, Longfellow went to bed with severe stomach pain. He endured the pain for several days with the help of opium before he died surrounded by family on Friday, March 24.[89] He had been suffering from peritonitis.[90] At the time of his death, his estate was worth an estimated $356,320.[83] He is buried with both of his wives at Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, Massachusetts. His last few years were spent translating the poetry of Michelangelo. Longfellow never considered it complete enough to be published during his lifetime, but a posthumous edition was collected in 1883. Scholars generally regard the work as autobiographical, reflecting the translator as an aging artist facing his impending death.[91]

Writing

Style

Much of Longfellow's work is categorized as lyric poetry, but he experimented with many forms, including hexameter and free verse.[92] His published poetry shows great versatility, using anapestic and trochaic forms, blank verse, heroic couplets, ballads, and sonnets.[93] Typically, he would carefully consider the subject of his poetic ideas for a long time before deciding on the right metrical form for it.[94] Much of his work is recognized for its melodious musicality.[95] As he says, "what a writer asks of his reader is not so much to like as to listen".[96]

As a very private man, Longfellow did not often add autobiographical elements to his poetry. Two notable exceptions are dedicated to the death of members of his family. "Resignation" was written as a response to the death of his daughter Fanny in 1848; it does not use first-person pronouns and is instead a generalized poem of mourning.[97] The death of his second wife Frances, as biographer Charles Calhoun wrote, deeply affected Longfellow personally but "seemed not to touch his poetry, at least directly".[98] His memorial poem to her was the sonnet "The Cross of Snow" and was not published in his lifetime.[97]

Longfellow often used didacticism in his poetry, though he focused on it less in his later years.[99] Much of his poetry imparts cultural and moral values, particularly focused on life being more than material pursuits.[100] He also often used allegory in his work. In "Nature", for example, death is depicted as bedtime for a cranky child.[101] Many of the metaphors that he used in his poetry came from legends, mythology, and literature.[102] He was inspired, for example, by Norse mythology for "The Skeleton in Armor" and by Finnish legends for The Song of Hiawatha.[103]

Longfellow rarely wrote on current subjects and seemed detached from contemporary American concerns.[104] Even so, he called for the development of high quality American literature, as did many others during this period. In Kavanagh, a character says:

We want a national literature commensurate with our mountains and rivers ... We want a national epic that shall correspond to the size of the country ... We want a national drama in which scope shall be given to our gigantic ideas and to the unparalleled activity of our people ... In a word, we want a national literature altogether shaggy and unshorn, that shall shake the earth, like a herd of buffaloes thundering over the prairies.[105]

He was also important as a translator; his translation of Dante became a required possession for those who wanted to be a part of high culture.[106] He encouraged and supported other translators, as well. In 1845, he published The Poets and Poetry of Europe, an 800-page compilation of translations made by other writers, including many by his friend and colleague Cornelius Conway Felton. Longfellow intended the anthology "to bring together, into a compact and convenient form, as large an amount as possible of those English translations which are scattered through many volumes, and are not accessible to the general reader".[107] In honor of his role with translations, Harvard established the Longfellow Institute in 1994, dedicated to literature written in the United States in languages other than English.[108]

In 1874, Longfellow oversaw a 31-volume anthology called Poems of Places which collected poems representing several geographical locations, including European, Asian, and Arabian countries.[109] Emerson was disappointed and reportedly told Longfellow: "The world is expecting better things of you than this ... You are wasting time that should be bestowed upon original production".[110] In preparing the volume, Longfellow hired Katherine Sherwood Bonner as an amanuensis.[111]

Critical response

Fellow Portland, Maine native John Neal published the first substantial praise of Longfellow's work.[112] In the January 1828 issue of his magazine The Yankee, he wrote, "As for Mr. Longfellow, he has a fine genius and a pure and safe taste, and all that he wants, we believe, is a little more energy, and a little more stoutness."[113]

Longfellow's early collections Voices of the Night and Ballads and Other Poems made him instantly popular. The New-Yorker called him "one of the very few in our time who has successfully aimed in putting poetry to its best and sweetest uses".[50] The Southern Literary Messenger immediately put Longfellow "among the first of our American poets".[50] Poet John Greenleaf Whittier said that Longfellow's poetry illustrated "the careful moulding by which art attains the graceful ease and chaste simplicity of nature".[114] Longfellow's friend Oliver Wendell Holmes, Sr. wrote of him as "our chief singer" and one who "wins and warms ... kindles, softens, cheers [and] calms the wildest woe and stays the bitterest tears!"[115]

The rapidity with which American readers embraced Longfellow was unparalleled in publishing history in the United States;[116] by 1874, he was earning $3,000 per poem.[117] His popularity spread throughout Europe, as well, and his poetry was translated during his lifetime into Italian, French, German, and other languages.[118] Scholar Bliss Perry suggests that criticizing Longfellow at that time was almost a criminal act equal to "carrying a rifle into a national park".[119] In the last two decades of his life, he often received requests for autographs from strangers, which he always sent.[120] John Greenleaf Whittier suggested that it was this massive correspondence which led to Longfellow's death: "My friend Longfellow was driven to death by these incessant demands".[121]

Contemporaneous writer Edgar Allan Poe wrote to Longfellow in May 1841 of his "fervent admiration which [your] genius has inspired in me" and later called him "unquestionably the best poet in America".[122] Poe's reputation increased as a critic, however, and he later publicly accused Longfellow of plagiarism in what Poe biographers call "The Longfellow War".[123] He wrote that Longfellow was "a determined imitator and a dextrous adapter of the ideas of other people",[122] specifically Alfred, Lord Tennyson.[124] His accusations may have been a publicity stunt to boost readership of the Broadway Journal, for which he was the editor at the time.[125] Longfellow did not respond publicly but, after Poe's death, he wrote: "The harshness of his criticisms I have never attributed to anything but the irritation of a sensitive nature chafed by some indefinite sense of wrong".[126]

Margaret Fuller judged Longfellow "artificial and imitative" and lacking force.[127] Poet Walt Whitman also considered him an imitator of European forms, though he praised his ability to reach a popular audience as "the expressor of common themes—of the little songs of the masses".[128] He added, "Longfellow was no revolutionarie: never traveled new paths: of course never broke new paths."[129] Lewis Mumford said that Longfellow could be completely removed from the history of literature without much effect.[104]

Toward the end of his life, contemporaries considered him as more of a children's poet,[130] as many of his readers were children.[131] A reviewer in 1848 accused Longfellow of creating a "goody two-shoes kind of literature ... slipshod, sentimental stories told in the style of the nursery, beginning in nothing and ending in nothing".[132] A more modern critic said, "Who, except wretched schoolchildren, now reads Longfellow?"[104] A London critic in the London Quarterly Review, however, condemned all American poetry—"with two or three exceptions, there is not a poet of mark in the whole union"—but he singled out Longfellow as one of those exceptions.[133] An editor of the Boston Evening Transcript wrote in 1846, "Whatever the miserable envy of trashy criticism may write against Longfellow, one thing is most certain, no American poet is more read".[134]

Legacy

Longfellow was the most popular poet of his day.[135] As a friend once wrote, "no other poet was so fully recognized in his lifetime".[136] Many of his works helped shape the American character and its legacy, particularly with the poem "Paul Revere's Ride".[119] He was such an admired figure in the United States during his life that his 70th birthday in 1877 took on the air of a national holiday, with parades, speeches, and the reading of his poetry.

Over the years, Longfellow's personality has become part of his reputation. He has been presented as a gentle, placid, poetic soul, an image perpetuated by his brother Samuel Longfellow who wrote an early biography which specifically emphasized these points.[137] As James Russell Lowell said, Longfellow had an "absolute sweetness, simplicity, and modesty".[126] At Longfellow's funeral, his friend Ralph Waldo Emerson called him "a sweet and beautiful soul".[138] In reality, his life was much more difficult than was assumed. He suffered from neuralgia, which caused him constant pain, and he also had poor eyesight. He wrote to friend Charles Sumner: "I do not believe anyone can be perfectly well, who has a brain and a heart".[139] He had difficulty coping with the death of his second wife.[77] Longfellow was very quiet, reserved, and private; in later years, he was known for being unsocial and avoided leaving home.[140]

Longfellow had become one of the first American celebrities and was also popular in Europe. It was reported that 10,000 copies of The Courtship of Miles Standish sold in London in a single day.[141] Children adored him; "The Village Blacksmith"'s "spreading chestnut-tree" was cut down and the children of Cambridge had it converted into an armchair which they presented to him.[142] In 1884, Longfellow became the first non-British writer for whom a commemorative bust was placed in Poet's Corner of Westminster Abbey in London; he remains the only American poet represented with a bust.[143] In 1909, a statue of Longfellow was unveiled in Washington, DC, sculpted by William Couper. He was honored in March 2007 when the United States Postal Service issued a stamp commemorating him.

Longfellow's popularity rapidly declined, beginning shortly after his death and into the twentieth century, as academics focused attention on other poets such as Walt Whitman, Edwin Arlington Robinson, and Robert Frost.[144] In the twentieth century, literary scholar Kermit Vanderbilt noted, "Increasingly rare is the scholar who braves ridicule to justify the art of Longfellow's popular rhymings."[145] Twentieth-century poet Lewis Putnam Turco concluded that "Longfellow was minor and derivative in every way throughout his career ... nothing more than a hack imitator of the English Romantics."[146]

List of works

.jpg)

- Outre-Mer: A Pilgrimage Beyond the Sea (Travelogue) (1835)

- Hyperion, a Romance (1839)

- The Spanish Student. A Play in Three Acts (1843)[57]

- Evangeline: A Tale of Acadie (epic poem) (1847)

- Kavanagh (1849)

- The Golden Legend (poem) (1851)

- The Song of Hiawatha (epic poem) (1855)

- The New England Tragedies (1868)

- The Divine Tragedy (1871)

- Christus: A Mystery (1872)

- Aftermath (poem) (1873)

- The Arrow and the Song (poem)

- Poetry collections

- Voices of the Night (1839)

- Ballads and Other Poems (1841)

- Poems on Slavery (1842)

- The Belfry of Bruges and Other Poems (1845)

- The Seaside and the Fireside (1850)

- The Poetical Works of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (London, 1852), with illustrations by John Gilbert

- The Courtship of Miles Standish and Other Poems (1858)

- Tales of a Wayside Inn (1863)

- Also included Birds of Passage (1863)

- Household Poems (1865)

- Flower-de-Luce (1867)

- Three Books of Song (1872)[109]

- The Masque of Pandora and Other Poems (1875)[109]

- Kéramos and Other Poems (1878)[109]

- Ultima Thule (1880)[109]

- In the Harbor (1882)[109]

- Michel Angelo: A Fragment (incomplete; published posthumously)[109]

- Translations

- Coplas de Don Jorge Manrique (Translation from Spanish) (1833)

- Dante's Divine Comedy (Translation) (1867)

- Anthologies

- Poets and Poetry of Europe (Translations) (1844)[57]

- The Waif (1845)[57]

- Poems of Places (1874)[109]

See also

- Whom the gods would destroy

- Alexander Wadsworth Longfellow Jr., his nephew

- The Golden Legend (cantata), a musical adaptation by Sullivan and Bennett, of his poem The Golden Legend

References

Citations

- Calhoun (2004), p. 5.

- Sullivan (1972), p. 180.

- Wadsworth–Longfellow Genealogy at Henry Wadsworth Longfellow – A Maine Historical Society Web Site

- https://famouskin.com/famous-kin-chart.php?name=9317+richard+warren&kin=8053+henry+wadsworth+longfellow

- Arvin (1963), p. 7.

- Thompson (1938), p. 16.

- Farnham, Russell Clare and Dorthy Evelyn Crawford. A Longfellow Genealogy: Comprising the English Ancestry and Descendants of the Immigrant William Longfellow of Newbury, Massachusetts, and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. Walrus Publishers, 2002.

- "Direct Ancestors of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow" (PDF).

- Arvin (1963), p. 11.

- Sullivan (1972), p. 181.

- Calhoun (2004), p. 24.

- Calhoun (2004), p. 16.

- McFarland (2004), pp. 58–59.

- Calhoun (2004), p. 33.

- "Winthrop Hall". bowdoin.edu. Retrieved July 31, 2016.

- Calhoun (2004), p. 37.

- Arvin (1963), p. 13.

- Sullivan (1972), p. 184.

- Arvin (1963), p. 14.

- Who Belongs To Phi Beta Kappa Archived January 3, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, Phi Beta Kappa website, accessed October 4, 2009

- Calhoun (2004), p. 40.

- Arvin (1963), p. 22.

- Calhoun (2004), p. 42.

- Inflation calculator for 1826

- Arvin (1963), p. 26.

- Sullivan (1972), p. 186.

- Jones, Brian Jay (2008). Washington Irving: An American Original. New York: Arcade Publishing. p. 242. ISBN 978-1559708364.

- Bursting, Andrew (2007). The Original Knickerbocker: The Life of Washington Irving. New York: Basic Books. p. 195. ISBN 978-0465008537.

- Calhoun (2004), p. 67.

- Calhoun (2004), p. 69.

- Williams (1964), p. 66.

- Irmscher (2006), p. 225.

- Thompson (1938), p. 199.

- Sullivan (1972), p. 187.

- Calhoun (2004), p. 90.

- Arvin (1963), p. 28.

- Williams (1964), p. 108.

- Arvin (1963), p. 30.

- Sullivan (1972), p. 189.

- Calhoun (2004), pp. 114–115.

- Calhoun (2004), p. 118.

- Sullivan (1972), p. 190.

- Arvin (1963), p. 305.

- Calhoun (2004), p. 124.

- Calhoun (2004), pp. 124–125.

- Brooks (1952), p. 153.

- Calhoun (2004), p. 137.

- Gioia (1993), p. 75.

- Williams (1964), p. 75.

- Calhoun (2004), p. 138.

- Calhoun (2004), p. 135.

- Sullivan (1972), p. 191.

- Rosenberg, Chaim M. (2010). The Life and Times of Francis Cabot Lowell, 1775–1817. Plymouth: Lexington Books. ISBN 978-0739146859.

- McFarland (2004), p. 59.

- Thompson (1938), p. 258.

- Sullivan (1972), p. 192.

- Calhoun (2004), p. 179.

- Irmscher (2006), p. 60.

- Thompson (1938), p. 332.

- Wagenknecht (1966), p. 56.

- Calhoun (2004), pp. 164–165.

- Arvin (1963), p. 51.

- Arvin (1963), p. 304.

- Sullivan (1972), p. 193.

- Calhoun (2004), p. 217.

- Calhoun (2004), p. 189.

- Williams (1964), p. 19.

- McFarland (2004), p. 198.

- Brooks (1952), p. 453.

- Calhoun (2004), p. 198.

- Robert L. Gale (2003). A Henry Wadsworth Longfellow Companion. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 143. ISBN 978-0-313-32350-8.

- McFarland (2004), p. 243.

- Calhoun (2004), p. 215.

- Arvin (1963), p. 138.

- McFarland (2004), p. 244.

- Arvin (1963), p. 139.

- Calhoun (2004), p. 218.

- Sullivan (1972), p. 197.

- Arvin (1963), p. 140.

- Calhoun (2004), p. 236.

- Irmscher (2006), p. 263.

- Irmscher (2006), p. 268.

- Williams (1964), p. 100.

- Jacob, Kathryn Allaying (2010). King of the Lobby: The Life and Times of Sam Ward, Man-About-Washington in the Gilded Age. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 98. ISBN 978-0801893971.

- Irmscher (2006), p. 205.

- Calhoun (2004), pp. 240–241.

- Wagenknecht (1966), p. 40.

- Irmscher (2006), p. 7.

- Calhoun (2004), p. 248.

- Wagenknecht (1966), p. 11.

- Irmscher (2006), pp. 137–139.

- Arvin (1963), p. 182.

- Williams (1964), p. 130.

- Williams (1964), p. 156.

- Brooks (1952), p. 174.

- Wagenknecht (1966), p. 145.

- Irmscher (2006), p. 46.

- Calhoun (2004), p. 229.

- Arvin (1963), p. 183.

- Howe, Daniel Walker (2007). What Hath God Wrought: The Transformation of America, 1815–1848. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 630–631. ISBN 978-0195078947.

- Loving, Jerome (1999). Walt Whitman: The Song of Himself. University of California Press. p. 52. ISBN 978-0520226876.

- Arvin (1963), p. 186.

- Brooks (1952), pp. 175–176.

- Arvin (1963), p. 321.

- Lewis, R. W. B. (1955). The American Adam: Innocence, Tragedy, and Tradition in the Nineteenth Century. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. p. 79.

- Calhoun (2004), p. 237.

- Irmscher (2006), p. 231.

- Irmscher (2006), p. 21.

- Calhoun (2004), p. 242.

- Irmscher (2006), p. 200.

- Wagenknecht (1966), p. 185.

- Lease, Benjamin (1972). That Wild Fellow John Neal and the American Literary Revolution. Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press. p. 129. ISBN 0-226-46969-7.

- Sears, Donald A. (1978). John Neal. Boston, Massachusetts: Twayne Publishers. p. 113, quoting Neal. ISBN 080-5-7723-08.

- Wagenknecht, Edward (1967). John Greenleaf Whittier: A Portrait in Paradox. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 113.

- Sullivan (1972), p. 177.

- Calhoun (2004), p. 139.

- Levine, Miriam (1984). A Guide to Writers' Homes in New England. Cambridge, MA: Apple-wood Books. p. 127. ISBN 978-0918222510.

- Irmscher (2006), p. 218.

- Sullivan (1972), p. 178.

- Calhoun (2004), p. 245.

- Irmscher (2006), p. 36.

- Meyers, Jeffrey (1992). Edgar Allan Poe: His Life and Legacy. New York: Cooper Square Press. p. 171. ISBN 978-0815410386.

- Silverman (1991), p. 250.

- Silverman (1991), p. 251.

- Calhoun (2004), p. 160.

- Wagenknecht (1966), p. 144.

- McFarland (2004), p. 170.

- Reynolds, David S. (1995). Walt Whitman's America: A Cultural Biography. New York: Vintage Books. p. 353. ISBN 978-0679767091.

- Blake, David Haven (2006). Walt Whitman and the Culture of American Celebrity. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. p. 74. ISBN 978-0300110173.

- Calhoun (2004), p. 246.

- Brooks (1952), p. 455.

- Douglas, Ann (1977). The Feminization of American Culture. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. p. 235. ISBN 978-0394405322.

- Silverman (1991), p. 199.

- Irmscher (2006), p. 20.

- Bayless (1943), p. 40.

- Gioia (1993), p. 65.

- Williams (1964), p. 18.

- Williams (1964), p. 197.

- Wagenknecht (1966), pp. 16–17.

- Wagenknecht (1966), p. 34.

- Brooks (1952), p. 523.

- Sullivan (1972), p. 198.

- Williams (1964), p. 21.

- Williams (1964), p. 23.

- Gioia (1993), p. 68.

- Turco, Lewis Putnam (1986). Visions and Revisions of American Poetry. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press. p. 33. ISBN 978-0938626497.

Sources

- Arvin, Newton (1963). Longfellow: His Life and Work. Boston: Little, Brown and Company.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bayless, Joy (1943). Rufus Wilmot Griswold: Poe's Literary Executor. Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Brooks, Van Wyck (1952). The Flowering of New England. New York: E. P. Dutton and Company.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Calhoun, Charles C (2004). Longfellow: A Rediscovered Life. Boston: Beacon Press. ISBN 978-0807070260.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gioia, Dana (1993). "Longfellow in the Aftermath of Modernism". In Parini, Jay (ed.). The Columbia History of American Poetry. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0231078368.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Irmscher, Christoph (2006). Longfellow Redux. University of Illinois. ISBN 978-0252030635.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- McFarland, Philip (2004). Hawthorne in Concord. New York: Grove Press. ISBN 978-0802117762.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Silverman, Kenneth (1991). Edgar A. Poe: Mournful and Never-ending Remembrance. New York: Harper Perennial. ISBN 978-0060923310.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sullivan, Wilson (1972). New England Men of Letters. New York: The Macmillan Company. ISBN 978-0027886801.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Thompson, Lawrance (1938). Young Longfellow (1807–1843). New York: The Macmillan Company.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wagenknecht, Edward (1966). Henry Wadsworth Longfellow: Portrait of an American Humanist. New York: Oxford University Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Williams, Cecil B (1964). Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. New York: Twayne Publishers, Inc.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: Henry Wadsworth Longfellow |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Henry Wadsworth Longfellow |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. |

Sources

- Poems by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow and biography at PoetryFoundation.org

- Works by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Henry Wadsworth Longfellow at Internet Archive

- Works by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Henry Wadsworth Longfellow: Profile and Poems at Poets.org

- Audio, hear "The Village Blacksmith"

- Maine Historical Society Searchable poem text database, biographical data, lesson plans.

Other

- Longfellow House–Washington's Headquarters National Historic Site in Cambridge, Massachusetts

- Wadsworth–Longfellow House in Portland, Maine

- Public Poet, Private Man: Henry Wadsworth Longfellow at 200 Online exhibition featuring material from the collection of Longfellow's papers at the Houghton Library, Harvard University.

- Longfellow's Translation of Dante rendered side by side with that of Cary and Norton

- Famous Quotations by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

- The Oliver Wendell Holmes Library at the Library of Congress has noteworthy representation volumes inscribed by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow.