Tunceli Province

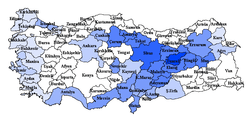

Tunceli Province (Kurdish: Parêzgeha Dêrsimê,[3] Turkish: Tunceli ili[4]Zazaki: Sûke Desim/Mamekiye,[5]), formerly Dersim Province, is located in the Eastern Anatolia region of Turkey. The least densely-populated province in Turkey (see Armenian Genocide), it was originally named Dersim Province (Dersim vilayeti), then demoted to a district (Dersim kazası) and incorporated into Elâzığ Province in 1926.[6] Many still call the region by its original name. The name of the provincial capital, Kalan, was changed to Tunceli to match the province's name. Tunceli is the only province in Turkey wih an Alevi majority, and Zazas are the largest ethnic group.

Tunceli Province | |

|---|---|

Location of Tunceli Province in Turkey | |

| Country | Turkey |

| Region | Central East Anatolia |

| Subregion | Malatya |

| Foundation | 25 December 1935 |

| Government | |

| • Electoral district | Tunceli |

| • Governor | Mehmet Ali Özkan |

| Area | |

| • Total | 7,774 km2 (3,002 sq mi) |

| Population (2018)[1] | |

| • Total | 88,198 |

| • Density | 11/km2 (29/sq mi) |

| Area code(s) | 0428[2] |

| Vehicle registration | 62 |

Geography

The adjacent provinces are Erzincan to the north and west, Elazığ to the south, and Bingöl to the east. The province covers an area of 7,774 km2 (3,002 sq mi) and has a population of 76,699. Tunceli is traversed by the northeasterly line of equal latitude and longitude.The Munzur Valley National Park is also situated in the province.[7]

History

The history of the province stretches back to antiquity. It was mentioned as Daranalis by Ptolemy, and seemingly, it was referred to as Daranis before him. One theory as to the origin of the name associates with Darius the Great. Another, more likely hypothesis, considering the region's Armenian background, says the name Daranalis or Daranaghis comes from the historical Armenian province of Daron, of which Dersim belonged.

The area that would become Dersim province formed part of Urartu, Media, the Achaemenid Empire, and the Greater Armenian region of Sophene. Sophene was later contested by the Roman and Parthian Empires and by their respective successors, the Byzantine and Sasanian Empires. Arabs invaded in the 7th century, and Seljuq Turks in the 11th.[8]

As of the end of the 19th century, the region, called Dersim, was included in the Ottoman sancak (sub-province) of Hozat, including the city and the Mamuret-ul-Aziz Vilayet (now Elazığ), with the exception of the actual district of Pülümür, which was in the neighboring sancak of Erzincan, then a part of the Erzurum Vilayet. This status continued through the first years of the Republic of Turkey, until 1936 when the name of the province ("Dersim") was changed to Tunceli, literally 'the land of bronze' in Turkish (tunç meaning 'bronze' and el (in this context) meaning 'land') after the brutal events of the Dersim rebellion. The town of Kalan was made the capital and the district of Pülümür was included in the new province.

Inspectorate General

Following the Tunceli Law 1935, which demanded a more powerful Government in the region, the Fourth Inspectorate-General (Umumi Müfettişlik, UM) was created in January 1936.[9] The fourth UM span over the provinces of Elaziğ, Erzincan, Bingöl and Tunceli,[10] and was governed by a Governor Commander. Most of the employees in the municipality were to be filled with military personnel and the Governor-Commander had the authority to evacuate whole villages and resettle them in other parts.[10] Also the juridical guarantees did not comply with the law in the other parts in Turkey. The trials were at most 15 days long and sentences could not be appealed. For a release, the Governor Commander had to give his consent. The application of the death penalty was under the authority of the Governor-Commander, while normally it would be the authority of the Grand National Assembly of Turkey to approve such a punishment.[10] In 1946 the Tunceli Law was abolished and the state of emergency removed but the authority of the fourth UM was transferred to the military.[10] The Inspectorates-General was dissolved in 1952 during the Government of the Democrat Party.[11]

Demographics

It has the lowest population density of any province in Turkey, just 9.8 inhabitants/km2. The majority of the population is Kurdish (Zaza and Kurmanji respectfully).[12] Tunceli is the only province of Turkey with an Alevi majority.

Armenians of Tunceli

The Armenians of Dersim lived peacefully alongside the Alevi Zazas, who partially assimilated into and had various Armenian beliefs.[13] Many of the region's Armenians were living among the Alevi Zazas of the region, with whom they had good relations.[14] This allowed the Armenians to avoid deportation because their Alevi neighbors didn't have any negative affinity towards Armenians, and as explained before were somewhat Armenian themselves. The Armenians lived quietly in their mountain villages until 1938, when Turkish Armed Forces soldiers invaded the region to put down a Dersim rebellion, and in the process blew up St Karapet's Monastery and killed around 60,000-70,000[15][16] Alevis and Armenians alike, causing an abrupt end to any open Armenian life in the province. Armenians now were forced to assimilate fully into the Alevi population, moving from their majority Armenian villages to blend in better with the population, and therefore becoming Hidden Armenians.[17]

Tunceli Alevis

They have been practicing Alevism before the Ottoman Empire came to the Middle East and many believe Munzur, Dersim to be the heartland of the Alevi. Where holy places, all of which are natural features of the landscape, are found in abundance, and where the region's isolation has insulated it from the influence of Turkeys' dominant Sunni sect of Islam, helping to keep its unique Alevi character relatively pure.[18] An example of this would be Newroz, the Kurdish New Year and a key date in Zoroastrian. The Alevi Kurds come out to sing and dance around the fire, they dress in traditional clothing, wear a red band over their heads and play soft music to their land.

The Alevi Kurds have a history of being attacked and discriminated against by Sunni Muslims in the past, both by the Ottoman Empire and Kurdish Sunni Muslims from other provinces due to their beliefs. "If you really call yourself Alevi, there is not really room for it in Islam," says Kadir Bulut, who is one of the few remaining "dedes" in Tunceli.[19] "Davutoglu's visit was an attempt at assimilation, he tried to define a Muslim, and we do not want this," says Engin Dogru, head of the Kurdish Democratic Regions Party in Tunceli.[19]

Name changes

It is said that ancient Greek historians and geographers named the Dersim region Daranis and Derksene. Baytar Nuri includes this information at the entrance of his book Dersim in Kurdistan history.[20] After the Dersim rebellion, any villages and towns deemed to have non-Turkish names were renamed and given Turkish names in order to suppress any non-Turkish heritage.[21][22][23][24][25][26][27][28][23][29] During the Turkish Republican era, the words Kurdistan and Kurds were banned. The Turkish government had disguised the presence of the Kurds statistically by categorizing them as Mountain Turks.[30][31]

Nişanyan estimates that 4,000 Kurdish geographical locations have been changed (both Zazaki and Kurmanji).[32] The people of Tunceli have been actively fighting to get their province reverted to its old Kurdish name "Dersim". Turkey's ruling Justice and Development Party (AK Party) claimed they are working on what it called a “democratization package” that includes the restoration of the Kurdish name of the eastern province of Tunceli back to Dersim in early 2013, but there has been no updates or news of it since then.[33]

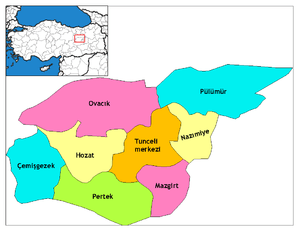

Districts

Tunceli Province is divided into eight districts:

Although a distinct province, Tunceli was administered from Elazığ until 1947.

Cities and towns

Education

98% of Tunceli's population has at least a primary school education, leading to one of the highest rates of literacy for a district within Turkey. In 1979/1980 Tunceli had the highest number of students attending universities as well as the top entry points, until the only higher education school shut down and was converted to a military base.

Tunceli University was established on May 22, 2008.[34] It has departments in international relations, economics, environmental protection engineering, industrial engineering, electronic engineering, computer engineering and mechanical engineering.

Places of interest

Tunceli is known for its old buildings such as the Çelebi Ağa Mosque,[35] Elti Hatun Mosque,[36] Mazgirt Castle,[37] Pertek Castle,[38] and the Derun-i Hisar Castle.[39][40]

References

- "Population of provinces by years - 2000-2018". Turkish Statistical Institute. Retrieved 9 March 2019.

- Area codes page of Turkish Telecom website Archived 2011-08-22 at the Wayback Machine (in Turkish)

- "Li Dêrsimê şer". Rûpela nû (in Kurdish). 27 August 2019. Retrieved 17 December 2019.

- "Mevcut İller Listesi" (PDF) (in Turkish). İller idaresi. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 April 2015. Retrieved 15 January 2015.

- Zazaca -Türkçe Sözlük, R. Hayıg-B. Werner

- Album of the Grand National Assembly of Turkey Archived 2013-08-01 at the Wayback Machine, Vol. 1, p. XXII, Dersim İli, 26.06.1926 tarih ve 404 sayılı Resmi Ceride'de yayımlanan 30.5.1926 tarih ve 877 sayılı Kanunla ilçeye dönüstürülerek Elazıg'a bağlanmıştır.

- "Munzur Valley National Park | National Parks Of Turkey". www.nationalparksofturkey.org. Retrieved 2020-04-11.

- Seyfi Cengiz Tarih (2005). History.

- Cagaptay, Soner (2 May 2006). Islam, Secularism and Nationalism in Modern Turkey: Who is a Turk?. Routledge. pp. 108–110. ISBN 978-1-134-17448-5.

- Bayir, Derya (2016-04-22). Minorities and Nationalism in Turkish Law. Routledge. pp. 139–141. ISBN 978-1-317-09579-8.

- Fleet, Kate; Kunt, I. Metin; Kasaba, Reşat; Faroqhi, Suraiya (2008-04-17). The Cambridge History of Turkey. Cambridge University Press. p. 343. ISBN 978-0-521-62096-3.

- Watts, Nicole F. (2010). Activists in Office: Kurdish Politics and Protest in Turkey (Studies in Modernity and National Identity). Seattle: University of Washington Press. p. 167. ISBN 978-0-295-99050-7.

- http://www.kirdki.com/images/kitaphane/Meqale%202.pdf

- Arakelova, Victoria; Grigorian, Christine. "The Halvori Vank': An Armenian Monastery and a Zaza Sanctuary". academia.edu. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- van Bruinessen, Martin (June 1994). "Genocide of the Kurds". In Charny, Israel W. (ed.). The Widening Circle of Genocide. New Brunswick, New York: Routledge. pp. 165–191. ISBN 9781351294072. Archived from the original on 1 November 2015. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- "The Dersim Massacre: Turkish Destruction of the Kurdish People in the Dersim Region". kurdistantribune.com. 10 May 2015. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- Kharatyan, Hranush. "The search for identity in Dersim Part 2: the Alevized Armenians in Dersim". repairfuture.net. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- Benanav, Michael (26 June 2015). "Finding Paradise in Turkey's Munzur Valley". Archived from the original on 17 October 2017. Retrieved 1 May 2018 – via NYTimes.com.

- Farooq, Umar. "Turkey's Alevis beholden to politics". www.aljazeera.com. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- Baytar Nuri Dersim, Dersim in the History of Kurdistan

- (Turkish) Tunçel H., "Türkiye'de İsmi Değiştirilen Köyler," Sosyal Bilimler Dergisi, Firat Universitesi, 2000, volume 10, number 2.

- Eren, editor, Ali Çaksu ; preface, Halit (2006). Proceedings of the second International Symposium on Islamic Civilization in the Balkans, Tirana, Albania, 4–7 December 2003 (in Turkish). Istanbul: Research Center for Islamic History, Art and Culture. ISBN 978-92-9063-152-1. Retrieved 12 January 2013.

- Boran, Sidar (12 August 2009). "Norşin ve Kürtçe isimler 99 yıldır yasak". Firatnews (in Turkish). Retrieved 13 January 2013.

- Nisanyan, Sevan (2011). Hayali Coğrafyalar: Cumhuriyet Döneminde Türkiye'de Değiştirilen Yeradları (PDF) (in Turkish). Istanbul: TESEV Demokratikleşme Programı. Retrieved 12 January 2013. Turkish: Memalik-i Osmaniyyede Ermenice, Rumca ve Bulgarca, hasılı İslam olmayan milletler lisanıyla yadedilen vilayet, sancak, kasaba, köy, dağ, nehir, ilah. bilcümle isimlerin Türkçeye tahvili mukarrerdir. Şu müsaid zamanımızdan süratle istifade edilerek bu maksadın fiile konması hususunda himmetinizi rica ederim."

- Nişanyan, Sevan (2010). Adını unutan ülke: Türkiye'de adı değiştirilen yerler sözlüğü (in Turkish) (1. ed.). İstanbul: Everest Yayınları. ISBN 978-975-289-730-4.

- Jongerden, edited by Joost; Verheij, Jelle. Social relations in Ottoman Diyarbekir, 1870–1915. Leiden: Brill. p. 300. ISBN 978-90-04-22518-3.

- Simonian, edited by Hovann H. (2007). The Hemshin: history, society and identity in the highlands of northeast Turkey (Repr. ed.). London: Routledge. p. 161. ISBN 978-0-7007-0656-3.

- Jongerden, Joost (2007). The settlement issue in Turkey and the Kurds : an analysis of spatial policies, modernity and war ([Online-Ausg.]. ed.). Leiden, the Netherlands: Brill. p. 354. ISBN 978-90-04-15557-2. Retrieved 12 January 2013.

- Tuncel, Harun (2000). "Türkiye'de İsmi Değiştirilen Köyler English: Renamed Villages in Turkey" (PDF). Fırat University Journal of Social Science (in Turkish). 10 (2). Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 November 2013. Retrieved 13 January 2013.

- Metz, Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. Ed. by Helen Chapin (1996). Turkey: a country study (5. ed., 1. print. ed.). Washington, DC: U.S. Government Print. Off. p. 139. ISBN 978-0-8444-0864-4. Retrieved 8 March 2013.

During the 1930s and 1940s, the government had disguised the presence of the Kurds statistically by categorizing them as "Mountain Turks."

- Bartkus, Viva Ona (1999). The dynamic of secession ([Online-Ausg.]. ed.). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. pp. 90–91. ISBN 978-0-521-65970-3. Retrieved 8 March 2013.

- Nisanyan, Sevan (2011). Hayali Coğrafyalar: Cumhuriyet Döneminde Türkiye'de Değiştirilen Yeradları (PDF) (in Turkish). Istanbul: TESEV Demokratikleşme Programı. Retrieved 12 January 2013. Turkish: Memalik-i Osmaniyyede Ermenice, Rumca ve Bulgarca, hasılı İslam olmayan milletler lisanıyla yadedilen vilayet, sancak, kasaba, köy, dağ, nehir, ilah. bilcümle isimlerin Türkçeye tahvili mukarrerdir. Şu müsaid zamanımızdan süratle istifade edilerek bu maksadın fiile konması hususunda himmetinizi rica ederim.

- "After 78 years, Turkey to restore Tunceli's original name". TodaysZaman. Archived from the original on 2016-02-24. Retrieved 2016-02-16.

- "Tunceli University Signs Protocol with 4 American Universities". turkishdailymail.com. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- "ÇELEBİ AĞA CAMİİ". Kültür Portalı. Retrieved 2020-04-11.

- "Pushover Analysis of Historical Elti Hatun Mosque" (PDF). Semantic Scholar. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- Sinclair, T. A. (31 December 1989). Eastern Turkey: An Architectural & Archaeological Survey, Volume III. Pindar Press. p. 148. ISBN 978-1-904597-78-0.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2016-10-20. Retrieved 2016-10-19.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2017-12-01. Retrieved 2017-11-18.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "DERUN-İ HİSAR (SAĞMAN) KALESİ". Kültür Portalı. Retrieved 2020-04-11.

External links

- Official Homepage of the Province Governor

- Official Homepage of the Culture and Tourism head office

- Official Homepage of the police head office

- Official Homepage of the Education head office

- Official Homepage of the health head office

- Tunceli University. Archived 7 August 2014.

- Captain L. Molyneux-Seel, A Journey in Dersim