Thrace

Thrace (/θreɪs/; Greek: Θράκη, Thráki; Bulgarian: Тракия, Trakiya; Turkish: Trakya) is a geographical and historical region in Southeast Europe, now split among Bulgaria, Greece, and Turkey, which is bounded by the Balkan Mountains to the north, the Aegean Sea to the south, and the Black Sea to the east. It comprises southeastern Bulgaria (Northern Thrace), northeastern Greece (Western Thrace), and the European part of Turkey (East Thrace). The region's boundaries are based on that of the Roman Province of Thrace; the lands inhabited by the ancient Thracians extended in the north to modern-day Northern Bulgaria and Romania and to the west into the region of Macedonia.

Etymology

The word Thrace was first used by the Greeks when referring to the Thracian tribes, from ancient Greek Thrake (Θρᾴκη),[1] descending from Thrāix (Θρᾷξ).[2] It referred originally to the Thracians, an ancient people inhabiting Southeast Europe. The name Europe first referred to Thrace proper, prior to the term vastly extending to refer to its modern concept.[3][4] The region could have been named after the principal river there, Hebros, possibly from the Indo-European arg "white river" (the opposite of Vardar, meaning "black river"),[5] According to an alternative theory, Hebros means "goat" in Thracian.[6]

In Turkey, it is commonly referred to as Rumeli, Land of the Romans, owing to this region being the last part of the Eastern Roman Empire that was conquered by the Ottoman Empire.

Geography

Borders

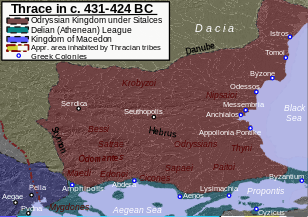

The historical boundaries of Thrace have varied. The ancient Greeks employed the term "Thrace" to refer to all of the territory which lay north of Thessaly inhabited by the Thracians,[7] a region which "had no definite boundaries" and to which other regions (like Macedonia and even Scythia) were added.[8] In one ancient Greek source, the very Earth is divided into "Asia, Libya, Europa and Thracia".[8] As the Greeks gained knowledge of world geography, "Thrace" came to designate the area bordered by the Danube on the north, by the Euxine Sea (Black Sea) on the east, by northern Macedonia in the south and by Illyria to the west.[8] This largely coincided with the Thracian Odrysian kingdom, whose borders varied over time. After the Macedonian conquest, this region's former border with Macedonia was shifted from the Struma River to the Mesta River.[9][10] This usage lasted until the Roman conquest. Henceforth, (classical) Thrace referred only to the tract of land largely covering the same extent of space as the modern geographical region. In its early period, the Roman province of Thrace was of this extent, but after the administrative reforms of the late 3rd century, Thracia's much reduced territory became the six small provinces which constituted the Diocese of Thrace. The medieval Byzantine theme of Thrace contained only what today is East Thrace.

Cities

The largest cities of Thrace are: Istanbul, Çorlu, Tekirdağ, Plovdiv, Burgas, Edirne, Stara Zagora, Sliven, Yambol, Haskovo, Komotini, Alexandroupoli, Xanthi, and Kırklareli.

Demographics and religion

Most of the Bulgarian and Greek population are Orthodox Christians, while most of the Turkish inhabitants of Thrace are Sunni Muslims.

Ancient Greek mythology

Ancient Greek mythology provides the Thracians with a mythical ancestor Thrax, the son of the war-god Ares, who was said to reside in Thrace. The Thracians appear in Homer's Iliad as Trojan allies, led by Acamas and Peiros. Later in the Iliad, Rhesus, another Thracian king, makes an appearance. Cisseus, father-in-law to the Trojan elder Antenor, is also given as a Thracian king.

Homeric Thrace was vaguely defined, and stretched from the River Axios in the west to the Hellespont and Black Sea in the east. The Catalogue of Ships mentions three separate contingents from Thrace: Thracians led by Acamas and Peiros, from Aenus; Cicones led by Euphemus, from southern Thrace, near Ismaros; and from the city of Sestus, on the Thracian (northern) side of the Hellespont, which formed part of the contingent led by Asius. Ancient Thrace was home to numerous other tribes, such as the Edones, Bisaltae, Cicones, and Bistones in addition to the tribe that Homer specifically calls the “Thracians”.

Greek mythology is replete with Thracian kings, including Diomedes, Tereus, Lycurgus, Phineus, Tegyrius, Eumolpus, Polymnestor, Poltys, and Oeagrus (father of Orpheus).

Thrace is mentioned in Ovid's Metamorphoses, in the episode of Philomela, Procne, and Tereus: Tereus, the King of Thrace, lusts after his sister-in-law, Philomela. He kidnaps her, holds her captive, rapes her, and cuts out her tongue. Philomela manages to get free, however. She and her sister, Procne, plot to get revenge, by killing her son Itys (by Tereus) and serving him to his father for dinner. At the end of the myth, all three turn into birds – Procne into a swallow, Philomela into a nightingale, and Tereus into a hoopoe.

The Dicaea city in Thrace was named after, the son of Poseidon, Dicaeus.[11]

History

Ancient and Roman history

The indigenous population of Thrace was a people called the Thracians, divided into numerous tribal groups. The region was controlled by the Persian Empire at its greatest extent,[12] and Thracian soldiers were known to be used in the Persian armies. Later on, Thracian troops were known to accompany neighboring ruler Alexander the Great when he crossed the Hellespont which abuts Thrace, during the invasion of the Persian Empire itself.

The Thracians did not describe themselves by name; terms such as Thrace and Thracians are simply the names given them by the Greeks.[13]

Divided into separate tribes, the Thracians did not form any lasting political organizations until the founding of the Odrysian state in the 4th century BC. Like Illyrians, the locally ruled Thracian tribes of the mountainous regions maintained a warrior tradition, while the tribes based in the plains were purportedly more peaceable. Recently discovered funeral mounds in Bulgaria suggest that Thracian kings did rule regions of Thrace with distinct Thracian national identity.

During this period, a subculture of celibate ascetics called the Ctistae lived in Thrace, where they served as philosophers, priests, and prophets.

Sections of Thrace particularly in the south started to become hellenized before the Peloponnesian War as Athenian and Ionian colonies were set up in Thrace before the war. Spartan and other Doric colonists followed them after the war. The special interest of Athens to Thrace is underlined by the numerous finds of Athenian silverware in Thracian tombs.[14] In 168 BC, after the Third Macedonian war and the subjugation of Macedonia to the Romans, Thrace also lost its independence and became tributary to Rome. Towards the end of the 1st century BC Thrace lost its status as a client kingdom as the Romans began to directly appoint their kings.[15] This situation lasted until 46 AD, when the Romans finally turned Thrace into a Roman province (Romana provincia Thracia)[16]

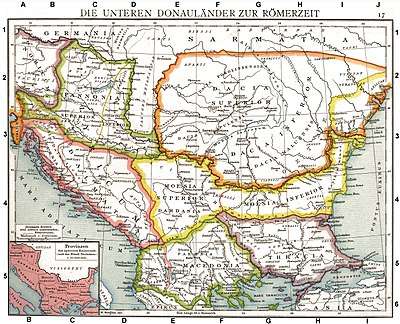

During the Roman domination, within the geographical borders of ancient Thrace, there were two separate Roman provinces, namely Thrace ("provincia Thracia") and Lower Moesia ("Moesia inferior"). Later, in the times of Diocletian, the two provinces were joined and formed the so-called "Dioecesis Thracia".[17] The establishment of Roman colonies and mostly several Greek cities, as was Nicopolis, Topeiros, Traianoupolis, Plotinoupolis, and Hadrianoupolis resulted from the Roman Empire's urbanization. That the Roman provincial policy in Thrace favored mainly not the Romanization but the Hellenization of the country, which had started as early as the Archaic period through the Greek colonisation and was completed by the end of Roman antiquity.[18] As regards the competition between the Greek and Latin language, the very high rate of Greek inscriptions in Thrace extending south of Haemus Mountains proves the complete language Hellenization of this region. The boundaries between the Greek and Latin speaking Thrace are placed just above the northern foothills of Haemus Mountains.[19]

During the imperial period many Thracians – particularly members of the local aristocracy of the cities – had been granted the right of the Roman citizenship (civitas Romana) with all its privileges. Epigraphic evidence show a large increase in such naturalizations in the times of Trajan and Hadrian, while in 212 AD the emperor Caracalla granted, with his well-known decree (constitutio Antoniniana), the Roman citizenship to all the free inhabitants of the Roman Empire.[20] During the same period (in the 1st-2nd century AD), a remarkable presence of Thracians is testified by the inscriptions outside the borders (extra fines) both in the Greek territory[21] and in all the Roman provinces, especially in the provinces of Eastern Roman Empire.[22]

Medieval history

By the mid 5th century, as the Western Roman Empire began to crumble, Thracia fell from the authority of Rome and into the hands of Germanic tribal rulers. With the fall of the Western Roman Empire, Thracia turned into a battleground territory for the better part of the next 1,000 years. The surviving eastern portion of the Roman Empire in the Balkans, later known as the Byzantine Empire, retained control over Thrace until the 7th century when the northern half of the entire region was incorporated into the First Bulgarian Empire and the remainder was reorganized in the Thracian theme. The Empire regained the lost regions in the late 10th century until the Bulgarians regained control of the northern half at the end of the 12th century. Throughout the 13th century and the first half of the 14th century, the region was changing in the hands of the Bulgarian and the Byzantine Empire (excluding Constantinople). In 1265 the area suffered a Mongol raid from the Golden Horde, led by Nogai Khan, and between 1305 and 1307 was raided by the Catalan company.[23]

Ottoman period

.svg.png)

In 1352, the Ottoman Turks conducted their first incursion into the region subduing it completely within a matter of two decades and occupying it for five centuries. In 1821, several parts of Thrace, such as Lavara, Maroneia, Sozopolis, Aenos, Callipolis, and Samothraki rebelled during the Greek War of Independence.

Modern history

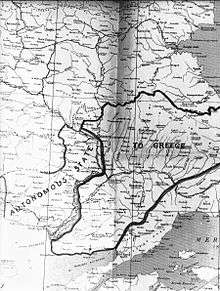

With the Congress of Berlin in 1878, Northern Thrace was incorporated into the semi-autonomous Ottoman province of Eastern Rumelia, which united with Bulgaria in 1885. The rest of Thrace was divided among Bulgaria, Greece and Turkey at the beginning of the 20th century, following the Balkan Wars, World War I and the Greco-Turkish War. In Summer 1934, up to 10,000 Jews[24] were maltreated, bereaved, and then forced to quit the region (see 1934 Thrace pogroms).

Today, Thracian is a geographical term used in Greece, Turkey, and Bulgaria.

Notable Thracians

- Orpheus was, in Ancient Greek mythology, the chief representative of the art of song and playing the lyre.

- Protagoras was a Greek philosopher from Abdera, Thrace (c. 490–420 BC.) An expert in rhetorics and subjects connected to virtue and political life, often regarded as the first sophist. He is known primarily for three claims: (1) that man is the measure of all things, often interpreted as a sort of moral relativism, (2) that he could make the "worse (or weaker) argument appear the better (or stronger)" (see Sophism), and (3) that one could not tell if the gods existed or not (see Agnosticism).

- Herodicus was a Greek physician of the fifth century BC who is considered the founder of sports medicine. He is believed to have been one of Hippocrates' tutors.

- Democritus was a Greek philosopher and mathematician from Abdera, Thrace (c. 460–370 BC.) His main contribution is the atomic theory, the belief that all matter is made up of various imperishable indivisible elements which he called atoms.

- Spartacus was a Thracian who led a large slave uprising in what is now Italy in 73–71 BC. His army of escaped gladiators and slaves defeated several Roman legions in what is known as the Third Servile War.

- A number of Roman emperors of the 3rd–5th century were of Thraco-Roman backgrounds (Maximinus Thrax, Licinius, Galerius, Aureolus, Leo the Thracian, etc.). These emperors were elevated via a military career, from the condition of common soldiers in one of the Roman legions to the foremost positions of political power.

Legacy

The Trakiya Heights in Antarctica "are named after the historical region."[25]

See also

- 1989 expulsion of Turks from Bulgaria

- Celtic settlement of Eastern Europe

- Dacia

- Dardania

- Destruction of Thracian Bulgarians in 1913

- Hawks of Thrace

- Macedon

- Moesia

- Moesogoths

- Music of Thrace

- Paionia

- Thracian treasure

- Turkish Republic of Thrace

Notes

- Θρᾴκη. Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; A Greek–English Lexicon at the Perseus Project

- Θρᾷξ. Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; A Greek–English Lexicon at the Perseus Project

- Greek goddess Europa adorns new five-euro note

- Pagden, Anthony (2002). "Europe: Conceptualizing a Continent" (PDF). The idea of Europe: from antiquity to the European Union. Washington, DC; Cambridge; New York: Woodrow Wilson Center Press ; Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511496813. ISBN 9780511496813.

- Pieter, Jan (1989). Thracians and Mycenaeans: Proceedings of the Fourth International Congress. ISBN 978-9004088641.

- "The Plovdiv Project".

- Swinburne Carr, Thomas (1838). The history and geography of Greece. Simpkin, Marshall & Company. p. 56.

- Smith, Sir William (1857). Dictionary of Greek and Roman geography. London. p. 1176.

- Johann Joachim Eschenburg, Nathan Welby Fiske (1855). Manual of classical literature. E.C. Biddle. p. 20 n.

- Adam, Alexander (1802). A summary of geography and history, both ancient and modern. A. Strahan. p. 344.

- Stephanus of Byzantium, Ethnica, §D230.14

- Joseph Roisman,Ian Worthington. "A companion to Ancient Macedonia" John Wiley & Sons, 2011. ISBN 144435163X p 343

- The Cambridge Ancient History, Volume 3, Part 2: The Assyrian and Babylonian Empires and Other States of the Near East, from the Eighth to the Sixth Centuries BC by John Boardman, I. E. S. Edwards, E. Sollberger, and N. G. L. Hammond ,ISBN 0-521-22717-8,1992,page 597: "We have no way of knowing what the Thracians called themselves and if indeed they had a common name...Thus the name of Thracians and that of their country were given by the Greeks to a group of tribes occupying the territory..."

- A. Sideris, Theseus in Thrace. The Silver Lining on the Clouds of the Athenian-Thracian Relations in the 5th Century BC (Sofia 2015), pp. 13-14, 79-82.

- D. C. Samsaris, Le royaume client thrace aux temps de Tibere et la tutelle romaine de Trebellenus Rufus (Le stade transitif de la clientele a la provincialisation de la Thrace), Dodona 17 (1), 1988, p. 159-168

- D. C. Samsaris, The Hellenization of Thrace during the Greek and Roman Antiquity (Diss. in Greek), Thessaloniki 1980, p. 26-36

- D. C. Samsaris, Historical Geography of Western Thrace during the Roman Antiquity (in Greek), Thessaloniki 2005, p. 7-14

- D. C. Samsaris, The Hellenization of Thrace, passim

- D. C. Samsaris, The Hellenization of Thrace, p. 320-330

- D. C. Samsaris, Surveys in the history, topography and cults of the Roman provinces of Macedonia and Thrace (in Greek), Thessaloniki 1984, p. 131-302

- D. C. Samsaris, Les Thraces dans l’ Empire romain d’ Orient (Le territoire de la Grèce actuelle). Etude ethno-démographique, sociale, prosopographique et anthroponymique, Jannina (Université) 1993, pp. 372

- D. C. Samsaris, Les Thraces dans l’ Empire romain d’ Orient (Asie Mineure, Syrie, Palestine et Arabie). Etude ethno-démographique et sociale, VIe Symposium Internazionale di Tracologia (Firenze 11-13 maggio 1989), Roma 1992, p. 184-204 [= Dodona 19(1990), fasc. 1, p. 5-30]

- La Venjança catalana. Gran Enciclopèdia Catalana.

- see footnote 4

- Trakiya Heights. SCAR Composite Antarctic Gazetteer.

References

- Hoddinott, R. F., The Thracians, 1981.

- Ilieva, Sonya, Thracology, 2001

External links

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Thrace. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ancient Thrace and Ancient Thracians. |

- Ethnological Museum of Thrace, comprehensive website on Thracian history and culture.

- Bulgaria's Thracian Heritage. including images of the comprehensive art collection of Thracian gold found on the territory of contemporary Bulgaria.

- Information on Ancient Thrace

- The People of the God-Sun Ar and Areia (modern Thrace)