Reykjavík

Reykjavík (/ˈreɪkjəvɪk, -viːk/ RAYK-yə-vik, -veek;[4] Icelandic: [ˈreiːcaˌviːk] (![]()

| Reykjavík | |

|---|---|

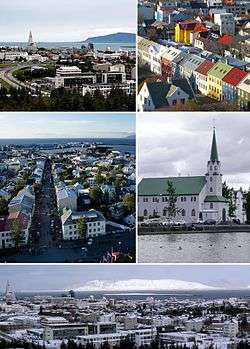

From upper left: View of old town and Hallgrímskirkja from Perlan, rooftops from Hallgrímskirkja, Reykjavík from Hallgrímskirkja, Fríkirkjan, panorama from Perlan | |

Coat of arms of Reykjavík | |

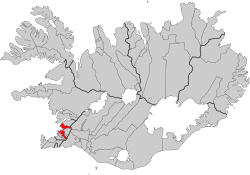

Location of Reykjavík | |

| Region | Capital Region |

| Constituency | Reykjavík Constituency North Reykjavík Constituency South |

| Market right | 18 August 1786[1] |

| Mayor | Dagur Bergþóruson Eggertsson (SDA) |

| Council | Reykjavík City Council |

| Area | 273 km2 (105 sq mi)[2] |

| Population | 131,136 (2020)[3] |

| Density | 471.77/km2 (1,221.9/sq mi) |

| Municipal number | 0000 |

| Postal code(s) | 101–155 |

| Website | reykjavik.is |

Reykjavík is believed to be the location of the first permanent settlement in Iceland, which, according to Landnámabók, was established by Ingólfr Arnarson in AD 874. Until the 19th century, there was no urban development in the city location. The city was founded in 1785 as an official trading town and grew steadily over the following decades, as it transformed into a regional and later national centre of commerce, population, and governmental activities. It is among the cleanest, greenest, and safest cities in the world.[6][7][8]

History

The first permanent settlement in Iceland by Norsemen is believed to have been established at Reykjavík by Ingólfr Arnarson around AD 870; this is described in Landnámabók, or the Book of Settlement. Ingólfur is said to have decided the location of his settlement using a traditional Norse method: he cast his high seat pillars (Öndvegissúlur) into the ocean when he saw the coastline, then settled where the pillars came to shore. This story is widely regarded as a legend; it appears likely that he settled near the hot springs to keep warm in the winter and would not have decided the location by happenstance. Furthermore, it seems unlikely that the pillars drifted to that location from where they were said to have been thrown from the boat. Nevertheless, that is what the Landnamabok says, and it says furthermore that Ingólfur's pillars are still to be found in a house in the town.

Steam from hot springs in the region is said to have inspired Reykjavík's name, which loosely translates to Smoke Cove (the city is sometimes referred to as Bay of Smoke or Smoky Bay in English language travel guides).[9][10] In the modern language, as in English, the word for 'smoke' and the word for fog or steamy vapour are not commonly confused, but this is believed to have been the case in the old language. The original name was Reykjarvík (with an additional "r" representing the usual genitive ending of strong nouns) but this had vanished around 1800.[11]

The Reykjavík area was farmland until the 18th century. In 1752, King Frederik V of Denmark donated the estate of Reykjavík to the Innréttingar Corporation; the name comes from the Danish-language word indretninger, meaning institution. The leader of this movement was Skúli Magnússon. In the 1750s, several houses were built to house the wool industry, which was Reykjavík's most important employer for a few decades and the original reason for its existence. Other industries were undertaken by the Innréttingar, such as fisheries, sulphur mining, agriculture, and shipbuilding.[12]

The Danish Crown abolished monopoly trading in 1786 and granted six communities around the country an exclusive trading charter. Reykjavík was one of them and the only one to hold on to the charter permanently. 1786 is thus regarded as the date of the city's founding. Trading rights were limited to subjects of the Danish Crown, and Danish traders continued to dominate trade in Iceland. Over the following decades, their business in Iceland expanded. After 1880, free trade was expanded to all nationalities, and the influence of Icelandic merchants started to grow.

Rise of nationalism

Icelandic nationalist sentiment gained influence in the 19th century, and the idea of Icelandic independence became widespread. Reykjavík, as Iceland's only city, was central to such ideas. Advocates of an independent Iceland realized that a strong Reykjavík was fundamental to that objective. All the important events in the history of the independence struggle were important to Reykjavík as well. In 1845 Alþingi, the general assembly formed in 930 AD, was re-established in Reykjavík; it had been suspended a few decades earlier when it was located at Þingvellir. At the time it functioned only as an advisory assembly, advising the king about Icelandic affairs. The location of Alþingi in Reykjavík effectively established the city as the capital of Iceland.

In 1874, Iceland was given a constitution; with it, Alþingi gained some limited legislative powers and in essence became the institution that it is today. The next step was to move most of the executive power to Iceland: Home Rule was granted in 1904 when the office of Minister For Iceland was established in Reykjavík. The biggest step towards an independent Iceland was taken on 1 December 1918 when Iceland became a sovereign country under the Crown of Denmark, the Kingdom of Iceland.

By the 1920s and 1930s most of the growing Icelandic fishing trawler fleet sailed from Reykjavík; cod production was its main industry, but the Great Depression hit Reykjavík hard with unemployment, and labour union struggles sometimes became violent.

World War II

On the morning of 10 May 1940, following the German occupation of Denmark and Norway on 9 April 1940, four British warships approached Reykjavík and anchored in the harbour. In a few hours, the allied occupation of Reykjavík was complete. There was no armed resistance, and taxi and truck drivers even assisted the invasion force, which initially had no motor vehicles. The Icelandic government had received many requests from the British government to consent to the occupation, but it always declined on the basis of the Neutrality Policy. For the remaining years of World War II, British and later American soldiers occupied camps in Reykjavík, and the number of foreign soldiers in Reykjavík became about the same as the local population of the city. The Royal Regiment of Canada formed part of the garrison in Iceland during the early part of the war.

The economic effects of the occupation were positive for Reykjavík: the unemployment of the Depression years vanished, and construction work began. The British built Reykjavík Airport, which is still in service today, mostly for short haul flights (to domestic destinations and Greenland). The Americans, meanwhile, built Keflavík Airport, situated 50 km (31 mi) west of Reykjavík, which became Iceland's primary international airport. In 1944, the Republic of Iceland was founded and a president, elected by the people, replaced the king; the office of the president was placed in Reykjavík.

Post-war development

In the post-war years, the growth of Reykjavík accelerated. An exodus from the rural countryside began, largely because improved technology in agriculture reduced the need for manpower, and because of a population boom resulting from better living conditions in the country. A once-primitive village was rapidly transformed into a modern city. Private cars became common, and modern apartment complexes rose in the expanding suburbs.

In 1972, Reykjavík hosted the world chess championship between Bobby Fischer and Boris Spassky. The 1986 Reykjavík Summit between Ronald Reagan and Mikhail Gorbachev underlined Reykjavík's international status. Deregulation in the financial sector and the computer revolution of the 1990s again transformed Reykjavík. The financial and IT sectors are now significant employers in the city. The city has fostered some world-famous talents in recent decades, such as Björk, Ólafur Arnalds and bands Múm, Sigur Rós and Of Monsters and Men, poet Sjón and visual artist Ragnar Kjartansson.

Geography

Reykjavík is located in the southwest of Iceland. The Reykjavík area coastline is characterized by peninsulas, coves, straits, and islands.

During the Ice Age (up to 10,000 years ago) a large glacier covered parts of the city area, reaching as far out as Álftanes. Other parts of the city area were covered by sea water. In the warm periods and at the end of the Ice Age, some hills like Öskjuhlíð were islands. The former sea level is indicated by sediments (with clams) reaching (at Öskjuhlíð, for example) as far as 43 m (141 ft) above the current sea level. The hills of Öskjuhlíð and Skólavörðuholt appear to be the remains of former shield volcanoes which were active during the warm periods of the Ice Age. After the Ice Age, the land rose as the heavy load of the glaciers fell away, and began to look as it does today.

The capital city area continued to be shaped by earthquakes and volcanic eruptions, like the one 4,500 years ago in the mountain range Bláfjöll, when the lava coming down the Elliðaá valley reached the sea at the bay of Elliðavogur.

The largest river to run through Reykjavík is the Elliðaá River, which is non-navigable. It is one of the best salmon fishing rivers in the country. Mount Esja, at 914 m (2,999 ft), is the highest mountain in the vicinity of Reykjavík.

The city of Reykjavík is mostly located on the Seltjarnarnes peninsula, but the suburbs reach far out to the south and east. Reykjavík is a spread-out city: most of its urban area consists of low-density suburbs, and houses are usually widely spaced. The outer residential neighbourhoods are also widely spaced from each other; in between them are the main traffic arteries and a lot of empty space. The city's latitude is 64°08' N, making it the world's northernmost capital of a sovereign state (Nuuk, the capital of Greenland, is slightly further north at 64°10', but Greenland is a constituent country, not an independent state).

Climate

Reykjavík has a subpolar oceanic climate (Köppen: Cfc)[13] closely bordering on a continental subarctic climate (Köppen: Dfc) in the 0 °C isoterm. While not much different from a tundra climate (Köppen : ET), the city has had its present climate classification since the beginning of the twentieth century.[14][15]

At 64° north, Reykjavik is characterized by extremes of day and night length over the course of the year. From 20 May to 24 July, daylight is essentially permanent as the sun never gets more than 5° below the horizon. Day length drops to less than five hours between 2 December and 10 January. The sun climbs just 3° above the horizon during this time. However, day length begins increasing rapidly during January and by month's end there are seven hours of daylight.

Despite its northern latitude, temperatures very rarely drop below −15 °C (5 °F) in the winter. The proximity to the Arctic Circle and the strong moderation of the Atlantic Ocean in the Icelandic coast (influence of North Atlantic Current, an extension of the Gulf Stream) shape a relatively mild winter and cool summer. The city's coastal location does make it prone to wind, however, and gales are common in winter. Summers are cool, with temperatures fluctuating between 10 and 15 °C (50 and 59 °F), rarely exceeding 20 °C (68 °F). This is a result of exposure to the maritime winds in its exposed west coast location that causes it to be way cooler in summer than similar latitudes in mainland Scandinavia. Rain in Reykjavík averages 147 days[16] at the threshold of 1 mm per year. Droughts are uncommon, although they occur in some summers. July and August are the warmest months of the year on average and January and February the coldest.

In the summer of 2007, no rain was measured for one month. Summer tends to be the sunniest season, although May receives the most sunshine of any individual month. Overall, the city receives around 1,300 annual hours of sunshine,[17] which is comparable with other places in northern and north-western Europe such as Ireland and Scotland, but substantially less than equally northern regions with a more continental climate, including the Bothnian Bay basin in Scandinavia. Nonetheless, Reykjavík is one of the cloudiest and coolest capitals of any nation in the world. The highest temperature recorded in Reykjavík was 25.7 °C (78 °F), reported on 30 July 2008,[18] while the lowest-ever recorded temperature was −19.7 °C (−3 °F), recorded on 30 January 1971.[19] The coldest month on record is January 1918, with a mean temperature of −7.2 °C (19 °F). The warmest is July 1917, with a mean temperature of 13.3 °C (56 °F). [20]

| Climate data for Reykjavík, 1981–2010 normals, extremes 1949–present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 10.7 (51.3) |

10.2 (50.4) |

13.0 (55.4) |

17.1 (62.8) |

20.6 (69.1) |

22.4 (72.3) |

25.7 (78.3) |

24.8 (76.6) |

18.5 (65.3) |

15.7 (60.3) |

12.6 (54.7) |

12.0 (53.6) |

25.7 (78.3) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 2.5 (36.5) |

2.8 (37.0) |

3.4 (38.1) |

6.1 (43.0) |

9.7 (49.5) |

12.4 (54.3) |

14.2 (57.6) |

13.6 (56.5) |

10.9 (51.6) |

7.0 (44.6) |

4.2 (39.6) |

3.1 (37.6) |

7.5 (45.5) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 0.1 (32.2) |

0.1 (32.2) |

0.6 (33.1) |

3.0 (37.4) |

6.6 (43.9) |

9.5 (49.1) |

11.2 (52.2) |

10.7 (51.3) |

8.0 (46.4) |

4.4 (39.9) |

1.9 (35.4) |

0.6 (33.1) |

4.7 (40.5) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −2.4 (27.7) |

−2.4 (27.7) |

−1.9 (28.6) |

0.5 (32.9) |

3.8 (38.8) |

7.0 (44.6) |

8.8 (47.8) |

8.4 (47.1) |

5.7 (42.3) |

2.2 (36.0) |

−0.5 (31.1) |

−1.8 (28.8) |

2.3 (36.1) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −19.7 (−3.5) |

−17.6 (0.3) |

−16.4 (2.5) |

−16.4 (2.5) |

−7.7 (18.1) |

−0.7 (30.7) |

1.4 (34.5) |

−0.4 (31.3) |

−4.4 (24.1) |

−10.6 (12.9) |

−15.1 (4.8) |

−16.8 (1.8) |

−19.7 (−3.5) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 83.0 (3.27) |

85.9 (3.38) |

81.4 (3.20) |

56.0 (2.20) |

52.8 (2.08) |

43.8 (1.72) |

52.3 (2.06) |

67.3 (2.65) |

73.5 (2.89) |

74.4 (2.93) |

78.8 (3.10) |

94.1 (3.70) |

843.3 (33.20) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 13.3 | 12.5 | 14.4 | 12.2 | 9.8 | 10.7 | 10.0 | 11.7 | 12.4 | 14.5 | 12.5 | 13.9 | 148.3 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 78.1 | 77.1 | 76.2 | 74.4 | 74.9 | 77.9 | 80.3 | 81.6 | 79.0 | 78.0 | 77.7 | 77.7 | 77.8 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 20 | 60 | 109 | 164 | 201 | 174 | 168 | 155 | 120 | 93 | 41 | 22 | 1,326 |

| Source: Icelandic Met Office (precipitation days 1961–1990)[21][22][23] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Reykjavík (sunshine data) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 20 | 60 | 109 | 164 | 201 | 174 | 168 | 155 | 120 | 93 | 41 | 22 | 1,327 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 11.7 | 24.9 | 29.0 | 36.0 | 35.0 | 27.8 | 27.8 | 30.8 | 30.9 | 31.0 | 21.2 | 16.3 | 26.9 |

| Average ultraviolet index | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Source 1: Icelandic Met Office (sunshine hours)[24] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: timeanddate.com (sunshine percent)[27]

and Weather Atlas (uv)[28] | |||||||||||||

Cityscape

Colourful rooftops line Reykjavík

Colourful rooftops line Reykjavík- Central Reykjavík seen from Hallgrímskirkja

- Looking southeast from Hallgrímskirkja

- Another view of Reykjavík from Hallgrímskirkja

- View from Skólavörðustígur

Tjörnin (The Pond) in Central Reykjavík

Tjörnin (The Pond) in Central Reykjavík Austurvöllur on a sunny day

Austurvöllur on a sunny day- View from Perlan

City administration

The Reykjavík City Council governs the city of Reykjavík[29] and is directly elected by those aged over 18 domiciled in the city. The council has 23 members who are elected using the open list method for four-year terms.

The council selects members of boards, and each board controls a different field under the city council's authority. The most important board is the City Board that wields the executive rights along with the City Mayor. The City Mayor is the senior public official and also the director of city operations. Other public officials control city institutions under the mayor's authority. Thus, the administration consists of two different parts:

- The political power of City Council cascading down to other boards

- Public officials under the authority of the city mayor who administer and manage implementation of policy.

Political control

The Independence Party was historically the city's ruling party; it had an overall majority from its establishment in 1929 until 1978, when it narrowly lost. From 1978 until 1982, there was a three-party coalition composed of the People's Alliance, the Social Democratic Party, and the Progressive Party. In 1982, the Independence Party regained an overall majority, which it held for three consecutive terms. The 1994 election was won by Reykjavíkurlistinn (the R-list), an alliance of Icelandic socialist parties, led by Ingibjörg Sólrún Gísladóttir. This alliance won a majority in three consecutive elections, but was dissolved for the 2006 election when five different parties were on the ballot. The Independence Party won seven seats, and together with the one Progressive Party they were able to form a new majority in the council which took over in June 2006.

In October 2007 a new majority was formed on the council, consisting of members of the Progressive Party, the Social Democratic Alliance, the Left-Greens and the F-list (liberals and independents), after controversy regarding REI, a subsidiary of OR, the city's energy company. However, three months later the F-list formed a new majority together with the Independence Party. Ólafur F. Magnússon, the leader of the F-list, was elected mayor on 24 January 2008, and in March 2009 the Independence Party was due to appoint a new mayor. This changed once again on 14 August 2008 when the fourth coalition of the term was formed, by the Independence Party and the Social Democratic Alliance, with Hanna Birna Kristjánsdóttir becoming mayor.

The City Council election in May 2010 saw a new political party, The Best Party, win six of 15 seats, and they formed a coalition with the Social Democratic Alliance; comedian Jón Gnarr became mayor.[30] At the 2014 election, the Social Democratic Alliance had its best showing yet, gaining five seats in the council, while Bright Future (successor to the Best Party) received two seats and the two parties formed a coalition with the Left-Green movement and the Pirate Party, which won one seat each. The Independence Party had its worst election ever, with only four seats.

Mayor

The mayor is appointed by the city council; usually one of the council members is chosen, but they may also appoint a mayor who is not a member of the council.

The post was created in 1907 and advertised in 1908. Two applications were received, from Páll Einarsson, sheriff and town mayor of Hafnarfjörður and from Knud Zimsen, town councillor in Reykjavík. Páll was appointed on 7 May and was mayor for six years. At that time the city mayor received a salary of 4,500 ISK per year and 1,500 ISK for office expenses. The current mayor is Dagur B. Eggertsson.[31]

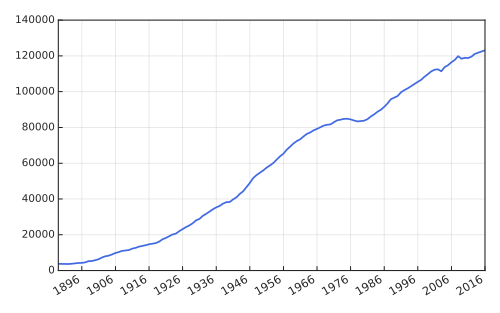

Demographics

Reykjavík is by far the largest and most populous settlement in Iceland. The municipality of Reykjavík had a population of 131,136 on 1 January 2020; that is 36% of the country's population. The Capital Region, which includes the capital and six municipalities around it, was home to 233,034 people; that is about 64% of the country's population.[32]

On 1 January 2019, of the city's population of 128,793, immigrants of the first and second generation numbered 23,995 (18.6%), increasing from 12,352 (10.4%) in 2008 and 3,106 (2.9%) in 1998.[33] The most common foreign citizens are Poles, Lithuanians, and Latvians. About 80% of the city's foreign residents originate in European Union and EFTA member states, and over 58% are from the new member states of the EU, mainly former Eastern Bloc countries, which joined in 2004, 2007 and 2013.[34]

Children of foreign origin form a more considerable minority in the city's schools: as many as a third in places.[35] The city is also visited by thousands of tourists, students, and other temporary residents, at times outnumbering natives in the city centre.[36]

| Citizenship[a] | 2018 | 2008 | 1998 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | % of total population |

% of foreign citizens |

Number | % of total population |

% of foreign citizens |

Number | % of total population |

% of foreign citizens | |

| 110,445 | 87.63% | 109,111 | 91.82% | 104,920 | 97.74% | ||||

| 5,526 | 4.38% | 35.43% | 3,146 | 2.65% | 32.38% | 95 | 0.09% | 3.92% | |

| 1,733 | 1.37% | 11.11% | 811 | 0.68% | 8.35% | 8 | 0.01% | 0.33% | |

| 595 | 0.47% | 3.82% | 217 | 0.18% | 2.23% | 1 | 0.00% | 0.04% | |

| 487 | 0.39% | 3.12% | 222 | 0.19% | 2.28% | 153 | 0.14% | 6.32% | |

| 482 | 0.38% | 3.09% | 87 | 0.07% | 0.90% | 41 | 0.04% | 1.69% | |

| 481 | 0.38% | 3.08% | 450 | 0.38% | 4.63% | 148 | 0.14% | 6.11% | |

| 420 | 0.33% | 2.69% | 331 | 0.28% | 3.41% | 313 | 0.29% | 12.93% | |

| 419 | 0.33% | 2.69% | 50 | 0.04% | 0.51% | 4 | 0.00% | 0.17% | |

| 409 | 0.32% | 2.62% | 453 | 0.38% | 4.66% | 110 | 0.10% | 4.54% | |

| 393 | 0.31% | 2.52% | 278 | 0.23% | 2.86% | 31 | 0.03% | 1.28% | |

| 371 | 0.29% | 2.38% | 145 | 0.12% | 1.49% | 71 | 0.07% | 2.93% | |

| 354 | 0.28% | 2.27% | 419 | 0.35% | 4.31% | 358 | 0.33% | 14.79% | |

| 243 | 0.19% | 1.56% | 207 | 0.17% | 2.13% | 43 | 0.04% | 1.78% | |

| 242 | 0.19% | 1.55% | 80 | 0.07% | 0.82% | 17 | 0.02% | 0.70% | |

| 216 | 0.17% | 1.38% | 286 | 0.24% | 2.94% | 155 | 0.14% | 6.40% | |

| 176 | 0.14% | 1.13% | 72 | 0.06% | 0.74% | 8 | 0.01% | 0.33% | |

| 172 | 0.14% | 1.10% | 48 | 0.04% | 0.49% | 3 | 0.00% | 0.12% | |

| 164 | 0.13% | 1.05% | 144 | 0.12% | 1.48% | 40 | 0.04% | 1.65% | |

| 156 | 0.12% | 1.00% | 201 | 0.17% | 2.07% | 117 | 0.11% | 4.83% | |

| 153 | 0.12% | 0.98% | 18 | 0.02% | 0.19% | 8 | 0.01% | 0.33% | |

| 127 | 0.10% | 0.81% | 91 | 0.08% | 0.94% | 3 | 0.00% | 0.12% | |

| 120 | 0.10% | 0.77% | 141 | 0.12% | 1.45% | 154 | 0.14% | 6.36% | |

| 115 | 0.09% | 0.74% | 57 | 0.05% | 0.59% | 17 | 0.02% | 0.70% | |

| 110 | 0.09% | 0.71% | 109 | 0.09% | 1.12% | 32 | 0.03% | 1.32% | |

| 109 | 0.09% | 0.70% | 7 | 0.01% | 0.07% | 3 | 0.00% | 0.12% | |

| 100 | 0.08% | 0.64% | 75 | 0.06% | 0.77% | 28 | 0.03% | 1.16% | |

| 81 | 0.06% | 0.52% | 89 | 0.07% | 0.92% | 9 | 0.01% | 0.37% | |

| 80 | 0.06% | 0.51% | 63 | 0.05% | 0.65% | 35 | 0.03% | 1.45% | |

| 73 | 0.06% | 0.47% | 86 | 0.07% | 0.89% | 10 | 0.01% | 0.41% | |

| 60 | 0.05% | 0.38% | 4 | 0.00% | 0.04% | 3 | 0.00% | 0.12% | |

| 60 | 0.05% | 0.38% | 25 | 0.02% | 0.26% | 13 | 0.01% | 0.54% | |

| 59 | 0.05% | 0.38% | 62 | 0.05% | 0.64% | 51 | 0.05% | 2.11% | |

| 56 | 0.04% | 0.36% | 16 | 0.01% | 0.16% | 5 | 0.00% | 0.21% | |

| 53 | 0.04% | 0.34% | 54 | 0.05% | 0.56% | 22 | 0.02% | 0.91% | |

| 50 | 0.04% | 0.32% | 1 | 0.00% | 0.01% | 0 | 0.00% | 0.00% | |

| 49 | 0.04% | 0.31% | 45 | 0.04% | 0.46% | 17 | 0.02% | 0.70% | |

| 48 | 0.04% | 0.31% | 32 | 0.03% | 0.33% | 11 | 0.01% | 0.45% | |

| 45 | 0.04% | 0.29% | 34 | 0.03% | 0.35% | 14 | 0.01% | 0.58% | |

| 43 | 0.03% | 0.28% | 69 | 0.06% | 0.71% | ||||

| 42 | 0.03% | 0.27% | 2 | 0.00% | 0.02% | 4 | 0.00% | 0.17% | |

| 40 | 0.03% | 0.26% | 15 | 0.01% | 0.15% | 12 | 0.01% | 0.50% | |

| 40 | 0.03% | 0.26% | 25 | 0.02% | 0.26% | 3 | 0.00% | 0.12% | |

| 39 | 0.03% | 0.25% | 15 | 0.01% | 0.15% | 1 | 0.00% | 0.04% | |

| 38 | 0.03% | 0.24% | 26 | 0.02% | 0.27% | 8 | 0.01% | 0.33% | |

| 37 | 0.03% | 0.24% | 28 | 0.02% | 0.29% | 9 | 0.01% | 0.37% | |

| 37 | 0.03% | 0.24% | 26 | 0.02% | 0.27% | 8 | 0.01% | 0.33% | |

| 34 | 0.03% | 0.22% | 40 | 0.03% | 0.41% | 5 | 0.00% | 0.21% | |

| 32 | 0.03% | 0.21% | 72 | 0.06% | 0.74% | 10 | 0.01% | 0.41% | |

| 30 | 0.02% | 0.19% | 6 | 0.01% | 0.06% | 4 | 0.00% | 0.17% | |

| 25 | 0.02% | 0.16% | 6 | 0.01% | 0.06% | 3 | 0.00% | 0.12% | |

| 24 | 0.02% | 0.15% | |||||||

| 23 | 0.02% | 0.15% | 23 | 0.02% | 0.24% | 2 | 0.00% | 0.08% | |

| 22 | 0.02% | 0.14% | 35 | 0.03% | 0.36% | 1 | 0.00% | 0.04% | |

| 20 | 0.02% | 0.13% | 40 | 0.03% | 0.41% | 2 | 0.00% | 0.08% | |

| 65 | 0.06% | 2.68% | |||||||

| Other Asia | 143 | 0.11% | 0.92% | 165 | 0.14% | 1.70% | 33 | 0.03% | 1.36% |

| Other Africa | 129 | 0.10% | 0.73% | 88 | 0.07% | 0.91% | 40 | 0.04% | 1.65% |

| Other Americas | 104 | 0.08% | 0.67% | 111 | 0.09% | 1.14% | 39 | 0.04% | 1.61% |

| Other Europe[f] | 41 | 0.03% | 0.26% | 223 | 0.19% | 2.29% | 81 | 0.08% | 3.35% |

| Stateless | 38 | 0.03% | 0.27% | 58 | 0.05% | 0.60% | 2 | 0.00% | 0.08% |

| Other Oceania | 11 | 0.01% | 0.07% | 10 | 0.01% | 0.10% | 0 | 0.00% | 0.00% |

| Other EU and EFTA | 8 | 0.01% | 0.08% | 5 | 0.00% | 0.05% | 0 | 0.00% | 0.00% |

| Total: | 12,583 | 9.98% | 80.68% | 6,835[h] | 5.75% | 70.35% | 1,258[i] | 1.17% | 51.96% |

| Total: Asia | 1,580 | 1.25% | 10.13% | 1,407 | 1.18% | 14.48% | 421 | 0.39% | 17.39% |

| Total: Nordic countries[j] | 689 | 0.55% | 4.42% | 823 | 0.69% | 8.47% | 680 | 0.63% | 28.09% |

| Total: Northern America | 500 | 0.40% | 3.21% | 394 | 0.33% | 4.06% | 348 | 0.32% | 14.37% |

| Total: Europe outside of EU and EFTA | 338 | 0.27% | 2.17% | 523 | 0.44% | 5.38% | 278 | 0.26% | 11.48% |

| Total: Africa | 296 | 0.23% | 1.90% | 237 | 0.20% | 2.44% | 73 | 0.07% | 3.02% |

| Total: Latin America and the Caribbean | 213 | 0.17% | 1.37% | 224 | 0.19% | 2.31% | 69 | 0.06% | 2.85% |

| Total: Oceania | 48 | 0.04% | 0.33% | 38 | 0.03% | 0.39% | 9 | 0.01% | 0.37% |

| Total foreign citizens | 15,596 | 12.37% | 100% | 9,716 | 8.18% | 100% | 2,421 | 2.26% | 100% |

| Total population | 126,041 | 100% | 118,827 | 100% | 107,341 | 100% | |||

| a Showing only countries with 20 or more citizens in the 2018 census. |

| b Including citizens of the Faroe Islands and Greenland. |

| c Not included in the 1998 census. See Yugoslavia. |

| d Included as part of Serbia in the 2008 census, and as part of Yugoslavia in the 1998 census. |

| e Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (1992–2006). Some persons who were registered as Yugoslavians after 1992 may in fact have origins in any of the six original republics of the union. |

| f Including citizens of unspecified countries of former Yugoslavia and the former Soviet Union. |

| g Including the Nordic countries except Iceland. |

| h Not including the 2013 enlargement of the European Union. |

| i Not including the 2004 and 2007 enlargement of the European Union. |

| j Excluding Iceland. |

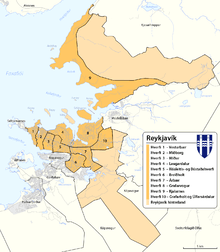

Districts

Reykjavík is divided into 10 districts:

- Vesturbær (District 1)

- Miðborg (District 2, city centre)

- Hlíðar (District 3)

- Laugardalur (District 4)

- Háaleiti og Bústaðir (District 5)

- Breiðholt (District 6)

- Árbær (District 7)

- Grafarvogur (District 8)

- Kjalarnes (District 9) (in the north)

- Grafarholt og Úlfarsárdalur (District 10)

In addition there are hinterland areas (lightly shaded on the map) which are not assigned to any district.

Economy

Borgartún is the financial centre of Reykjavík, hosting a large number of companies and three investment banks.

Reykjavík has been at the centre of Iceland's economic growth and subsequent economic contraction over the 2000s, a period referred to in foreign media as the "Nordic Tiger" years,[38][39] or "Iceland's Boom Years".[40] The economic boom led to a sharp increase in construction, with large redevelopment projects such as Harpa concert hall and conference centre and others. Many of these projects came to a screeching halt in the following economic crash of 2008.

Infrastructure

Roads

Per capita car ownership in Iceland is among the highest in the world at roughly 522 vehicles per 1,000 residents,[41] though Reykjavík is not severely affected by congestion. Several multi-lane highways (mainly dual carriageways) run between the most heavily populated areas and most frequently driven routes. Parking spaces are also plentiful in most areas. Public transportation consists of a bus system called Strætó bs. Route 1 (the Ring Road) runs through the city outskirts and connects the city to the rest of Iceland.

Airports and seaports

Reykjavík Airport, the second largest airport in the country (after Keflavík International Airport), is positioned inside the city, just south of the city centre. It is mainly used for domestic flights, as well as flights to Greenland and the Faroe Islands. Since 1962, there has been some controversy regarding the location of the airport, since it takes up a lot of valuable space in central Reykjavík.

Reykjavík has two seaports, the old harbour near the city centre which is mainly used by fishermen and cruise ships, and Sundahöfn in the east city which is the largest cargo port in the country.

Railways

There are no public railways in Iceland, because of its sparse population, but the locomotives used to build the docks are on display. Proposals have been made for a high-speed rail link between the city and Keflavík.

District heating

Volcanic activity provides Reykjavík with geothermal heating systems for both residential and industrial districts. In 2008, natural hot water was used to heat roughly 90% of all buildings in Iceland.[42] Of total annual use of geothermal energy of 39 PJ, space heating accounted for 48%.

Most of the district heating in Iceland comes from three main geothermal power plants:[43]

- Svartsengi combined heat and power plant (CHP)

- Nesjavellir CHP plant

- Hellisheiði CHP plant

Cultural heritage

Safnahúsið (the Culture House) was opened in 1909 and has a number of important exhibits. Originally built to house the National Library and National Archives and also previously the location of the National Museum and Natural History Museum, in 2000 it was re-modeled to promote the Icelandic national heritage. Many of Iceland's national treasures are on display, such as the Poetic Edda, and the Sagas in their original manuscripts. There are also changing exhibitions of various topics.[44]

Lifestyle

Nightlife

Alcohol is expensive at bars. People tend to drink at home before going out. Beer was banned in Iceland until 1 March 1989 but has since become popular among many Icelanders as their alcoholic drink of choice.[45]

Live music

The Iceland Airwaves music festival is staged annually in November. This festival takes place all over the city, and the concert venue Harpa is one of the main locations. Other venues that frequently organise live music events are Kex, Húrra, Gaukurinn (grunge, metal, punk), Mengi (centre for contemporary music, avant-garde music and experimental music), the Icelandic Opera and the National Theatre of Iceland for classical music.

New Year's Eve

The arrival of the new year is a particular cause for celebration to the people of Reykjavík. Icelandic law states that anyone may purchase and use fireworks during a certain period around New Year's Eve. As a result, every New Year's Eve the city is lit up with fireworks displays.

Main sights

- Alþingishúsið – the Icelandic parliament building

- Austurvöllur – a park in central Reykjavík surrounded by restaurants and bars

- Árbæjarsafn (Reykjavík Open Air Museum) – Reykjavík's Municipal Museum

- CIA.IS – Center for Icelandic Art – general information on Icelandic visual art

- Hallgrímskirkja – the largest church in Iceland

- Harpa Reykjavík – Reykjavík Concert & Conference Center

- Heiðmörk – the largest forest and nature reserve in the area

- Höfði – the house in which Gorbachev and Reagan met in 1986 for the Iceland Summit

- Kringlan – the second-largest shopping mall in Iceland

- Laugardalslaug – swimming pool

- Laugavegur – main shopping street

- National and University Library of Iceland (Þjóðarbókhlaðan)

- National Museum of Iceland (Þjóðminjasafnið)

- Nauthólsvík – a geothermally-heated beach

- Perlan – a glass dome resting on five water tanks

- Ráðhús Reykjavíkur – city hall

- Rauðhólar – a cluster of red pseudo- craters

- Reykjavík 871±2 – exhibition of an archaeological excavation of a Viking-age longhouse, from about AD 930

- Reykjavík Art Museum – the largest visual art institution in Iceland

- Safnahúsið, culture house, National Centre for Cultural Heritage (Þjóðmenningarhúsið)

- Tjörnin – the pond

- University of Iceland

- Vikin Maritime Museum – a maritime museum located by the old harbour

- Reykjavík Botanic Garden

Recreation

Reykjavik Golf Club was established in 1934. It is the oldest and largest golf club in Iceland. It consists of two 18-hole courses—one at Grafarholt and the other at Korpa. The Grafarholt golf course opened in 1963, which makes it the oldest 18-hole golf course in Iceland. The Korpa golf course opened in 1997.[46]

Education

Secondary schools

- Borgarholtsskóli (Borgó)

- Fjölbrautaskólinn í Breiðholti (FB)

- Fjölbrautaskólinn við Ármúla (FÁ)

- Kvennaskólinn í Reykjavík (Kvennó)

- Menntaskólinn Hraðbraut

- Menntaskólinn í Reykjavík (MR)

- Menntaskólinn við Hamrahlíð (MH)

- Menntaskólinn við Sund (MS)

- Tækniskólinn

- Verzlunarskóli Íslands (Verzló)

Universities

- Iceland Academy of the Arts

- Reykjavík University

- University of Iceland

International schools

Sports teams

Football

Other

|

|

Twin towns and sister cities

Reykjavík is twinned with:

|

In July 2013, mayor Jón Gnarr filed a motion before the city council to terminate the city's relationship with Moscow, in response to a trend of anti-gay legislation in Russia.[53]

Notable people

See also

References

- "Vísindavefurinn: Af hverju varð Reykjavík höfuðstaður Íslands?". Vísindavefurinn. Archived from the original on 13 August 2015. Retrieved 1 August 2015.

- "Vísindavefurinn: Hvað er Reykjavík margir metrar?". Vísindavefurinn. Archived from the original on 5 October 2015. Retrieved 1 August 2015.

- "Mannfjöldi eftir sveitarfélögum, kyni, ríkisfangi og ársfjórðungum 2010-2016". Hagstofa Íslands. Hagstofa Íslands. Retrieved 30 March 2017.

- "Reykjavik - definition of Reykjavik in English from the Oxford dictionary". www.oxforddictionaries.com. Archived from the original on 31 March 2016. Retrieved 29 March 2016.

- "Iceland: Major Urban Settlements - Population Statistics, Maps, Charts, Weather and Web Information". citypopulation.de. Archived from the original on 25 March 2019. Retrieved 25 March 2019.

- Yunlong, Sun (23 December 2007). "Reykjavík rated cleanest city in Nordic and Baltic countries". Xinhua News Agency. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 29 September 2013.

- "15 Green Cities". Grist. 20 July 2007. Archived from the original on 23 September 2013. Retrieved 29 September 2013.

- "Iceland among Top 10 safest countries and Reykjavík is the winner of Tripadvisor Awards". TRAVELIO.net. 20 May 2010. Archived from the original on 21 February 2014. Retrieved 29 September 2013.

- "Google.com". Archived from the original on 4 September 2015. Retrieved 25 July 2012.

- "Google.com". Retrieved 25 July 2012.

- Er eitthvert örnefni á höfuðborgarsvæðinu eða vík eða vogur, sem heitir Reykjavík? Archived 2017-11-07 at the Wayback Machine. Vísindavefur. (in Icelandic)

- Hvaðan kemur nafnið "Innréttingarnar" á fyrirtækinu sem starfaði hér á á 18. öld? Archived 2016-09-10 at the Wayback Machine. Vísindavefur. (in Icelandic)

- "Reykjavik, Iceland Köppen Climate Classification (Weatherbase)". Weatherbase. Retrieved 8 November 2018.

- "Köppen Climate Classification of 1900-2100". Archived from the original on 8 November 2018.

- "Shifts climate". Archived from the original on 30 November 2018.

- "Weather statistics for Reykjavik". yr.no. Archived from the original on 7 November 2015. Retrieved 26 October 2015.

- The weather of 2010 in Iceland Archived 2012-01-30 at the Wayback Machine Icelandic Met Office

- "Reykjavik sees record summer temperature". Agence France-Presse. July 31, 2008.

- "Nokkur íslensk veðurmet". Archived from the original on 18 November 2008. Retrieved 17 July 2008.

- "Temperaturmonatsmittel REYKJAVIK 1901- 1993". Retrieved 2020-27-03. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - "Monthly Averages for Reykjavík". Icelandic Meteorological Office. Retrieved 31 March 2020.

- "Annual Averages for Reykjavík". Icelandic Met Office. Retrieved 14 February 2016.

- "Reykjavík 1961-1990 Averages". Icelandic Meteorological Office. Retrieved 14 February 2016.

- "Monthly Averages for Reykjavík". Icelandic Met Office. Retrieved 22 June 2020.

- "Annual Averages for Reykjavík". Icelandic Met Office. Retrieved 22 June 2020.

- "Reykjavík 1961-1990 Averages". Icelandic Met Office. Retrieved 22 June 2020.

- "Reykjavík, Iceland - Sunrise, Sunset, and Daylength". timeanddate.com. Retrieved 22 June 2020.

- "Monthly weather forecast and climate - Reykjavík, Iceland". Weather Atlas. Retrieved 22 June 2020.

- "1998 nr. 45 3. júní/ Sveitarstjórnarlög". Althingi.is. Archived from the original on 21 October 2009. Retrieved 8 July 2009.

- "Best Party wins polls in Iceland's Reykjavík". BBC News Online. 30 May 2010. Retrieved 30 May 2010.

- Jón Glarr is no longer mayor of Reykjavík Archived 2016-03-23 at the Wayback Machine. Reykjavík Grapevine.

- "Population by municipality, age and sex 1998-2020 - Division into municipalites as of 1 January 2020". www.hagstofa.is. Statistics Iceland. 1 January 2020. Retrieved 12 May 2019.

- "Immigrants in Reykjavík by districts 1998-2019". www.hagstofa.is. Statistics Iceland. 1 January 2019. Retrieved 16 June 2019.

- "Population by municipality, age and sex 1998-2019 - Division into municipalites as of 1 January 2019". www.hagstofa.is. Statistics Iceland. 1 January 2019. Retrieved 12 May 2019.

- "Reykjavík – fjölmenningarborg barna" (PDF). 18 January 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 September 2013. Retrieved 7 July 2014.

- "Vísir - Breskir ferðamenn fjölmennastir sem fyrr". Visir.is. Archived from the original on 17 January 2012. Retrieved 15 September 2011.

- "Population by sex, municipality and citizenship 1 January 1998–2018". www.hagstofa.is. Statistics Iceland. 1 January 2018. Retrieved 13 June 2019.

- Surowiecki, James (21 April 2008). "Iceland's Deep Freeze". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on 2 March 2012. Retrieved 17 February 2012.

- Kvam, Berit (19 June 2009). "Iceland: light at the end of the tunnel?". Nordic Labour Journal. Archived from the original on 3 January 2012. Retrieved 17 February 2012.

- "Iceland: the boom years". The Telegraph. 18 August 2009. Archived from the original on 15 May 2018. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

- "Motor vehicles (most recent) by country". United Nations World Statistics Pocketbook. nationmaster.com. Archived from the original on 27 March 2010. Retrieved 29 March 2010.

- "NEA.is". NEA.is. Archived from the original on 24 July 2012. Retrieved 25 July 2012.

- "Mannvit". Mannvit. Archived from the original on 7 October 2011. Retrieved 25 July 2012.

- Guide leaflet to the Culture House 2008, published by the National Centre for Cultural Heritage.

- "The Dynamics of Shifts in Alcoholic Beverage Preference: Effects of the Legalization of Beer in Iceland". Questia.com. Archived from the original on 1 September 2008. Retrieved 8 July 2009.

- "Reykjavik Golf Club". Archived from the original on 5 May 2016. Retrieved 1 May 2016.

- "Christmas around the world". Hull in Print. Hull City Council. December 2006. Archived from the original on 30 May 2013. Retrieved 30 April 2014.

- "Convenio de amistad entre Ciudad de México y Reykjavík" (in Spanish). SEGOB. Archived from the original on 4 August 2014.

- Irvine, Chris (15 July 2013). "Reykjavik mayor proposes cutting ties with Moscow over gay law". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 25 July 2013. Retrieved 24 July 2013.

- "Reykjavík, Iceland - Sister Cities". Archived from the original on 4 September 2015. Retrieved 4 March 2015.

- "Vinarbýir - Tórshavnar kommuna". torshavn.fo. Archived from the original on 6 October 2016. Retrieved 30 April 2014.

- "Wrocław będzie miał nowe miasto partnerskie". tuwroclaw.com. Archived from the original on 23 March 2017. Retrieved 23 March 2017.

- "Sister Cities Ramp Up Russia Boycott Over Antigay Law". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. Archived from the original on 29 April 2014. Retrieved 30 April 2014.

Sources

- Hermannsdóttir, Edda (3 July 2006). "Consumption of alcoholic beverages 2005". Prices and consumption. Reykjavík: Hagstofa Íslands. Archived from the original on 14 December 2006. Retrieved 1 February 2007.

External links

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Reykjavík. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Reykjavík. |

- Official website (in Icelandic)