Fault (geology)

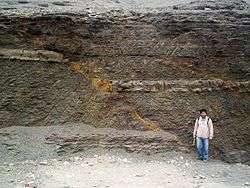

In geology, a fault is a planar fracture or discontinuity in a volume of rock across which there has been significant displacement as a result of rock-mass movement. Large faults within the Earth's crust result from the action of plate tectonic forces, with the largest forming the boundaries between the plates, such as subduction zones or transform faults.[1] Energy release associated with rapid movement on active faults is the cause of most earthquakes. Faults may also displace slowly, by aseismic creep.

| Part of a series on |

| Earthquakes |

|---|

|

Characteristics |

|

A fault plane is the plane that represents the fracture surface of a fault. A fault trace or fault line is a place where the fault can be seen or mapped on the surface. A fault trace is also the line commonly plotted on geologic maps to represent a fault.[2][3]

Since faults do not usually consist of a single, clean fracture, geologists use the term fault zone when referring to the zone of complex deformation associated with the fault plane.

Mechanisms of faulting

Owing to friction and the rigidity of the constituent rocks, the two sides of a fault cannot always glide or flow past each other easily, and so occasionally all movement stops. The regions of higher friction along a fault plane, where it becomes locked, are called asperities. Stress builds up when a fault is locked, and when it reaches a level that exceeds the strength threshold, the fault ruptures and the accumulated strain energy is released in part as seismic waves, forming an earthquake.

Strain occurs accumulatively or instantaneously, depending on the liquid state of the rock; the ductile lower crust and mantle accumulate deformation gradually via shearing, whereas the brittle upper crust reacts by fracture – instantaneous stress release – resulting in motion along the fault. A fault in ductile rocks can also release instantaneously when the strain rate is too great.

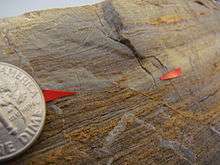

Slip, heave, throw

Slip is defined as the relative movement of geological features present on either side of a fault plane. A fault's sense of slip is defined as the relative motion of the rock on each side of the fault with respect to the other side.[4] In measuring the horizontal or vertical separation, the throw of the fault is the vertical component of the separation and the heave of the fault is the horizontal component, as in "Throw up and heave out".[5]

The vector of slip can be qualitatively assessed by studying any drag folding of strata, which may be visible on either side of the fault; the direction and magnitude of heave and throw can be measured only by finding common intersection points on either side of the fault (called a piercing point). In practice, it is usually only possible to find the slip direction of faults, and an approximation of the heave and throw vector.

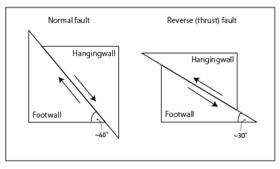

Hanging wall and footwall

The two sides of a non-vertical fault are known as the hanging wall and footwall. The hanging wall occurs above the fault plane and the footwall occurs below it.[6] This terminology comes from mining: when working a tabular ore body, the miner stood with the footwall under his feet and with the hanging wall above him.[7] These terms are important for distinguishing different dip-slip fault types: reverse faults and normal faults. In a reverse fault, the hanging wall displaces upward, while in a normal fault the hanging wall displaces downward. Distinguishing between these two fault types is important for determining the stress regime of the fault movement.

Fault types

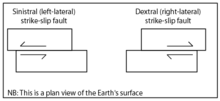

Based on the direction of slip, faults can be categorized as:

- strike-slip, where the offset is predominantly horizontal, parallel to the fault trace;

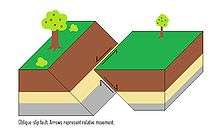

- dip-slip, offset is predominantly vertical and/or perpendicular to the fault trace; or

- oblique-slip, combining strike and dip slip.

Strike-slip faults

In a strike-slip fault (also known as a wrench fault, tear fault or transcurrent fault),[8] the fault surface (plane) is usually near vertical, and the footwall moves laterally either left or right with very little vertical motion. Strike-slip faults with left-lateral motion are also known as sinistral faults, and those with right-lateral motion as dextral faults.[9] Each is defined by the direction of movement of the ground as would be seen by an observer on the opposite side of the fault.

A special class of strike-slip fault is the transform fault, when it forms a plate boundary. This class is related to an offset in a spreading center, such as a mid-ocean ridge, or, less common, within continental lithosphere, such as the Dead Sea Transform in the Middle East or the Alpine Fault in New Zealand. Transform faults are also referred to as "conservative" plate boundaries, inasmuch as lithosphere is neither created nor destroyed.

Dip-slip faults

Dip-slip faults can be either normal ("extensional") or reverse.

In a normal fault, the hanging wall moves downward, relative to the footwall. A downthrown block between two normal faults dipping towards each other is a graben. An upthrown block between two normal faults dipping away from each other is a horst. Low-angle normal faults with regional tectonic significance may be designated detachment faults.

A reverse fault is the opposite of a normal fault—the hanging wall moves up relative to the footwall. Reverse faults indicate compressive shortening of the crust. The dip of a reverse fault is relatively steep, greater than 45°. The terminology of "normal" and "reverse" comes from coal-mining in England, where normal faults are the most common.[10]

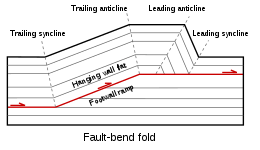

A thrust fault has the same sense of motion as a reverse fault, but with the dip of the fault plane at less than 45°.[11][12] Thrust faults typically form ramps, flats and fault-bend (hanging wall and footwall) folds.

Flat segments of thrust fault planes are known as flats, and inclined sections of the thrust are known as ramps. Typically, thrust faults move within formations by forming flats and climb up sections with ramps.

Fault-bend folds are formed by movement of the hanging wall over a non-planar fault surface and are found associated with both extensional and thrust faults.

Faults may be reactivated at a later time with the movement in the opposite direction to the original movement (fault inversion). A normal fault may therefore become a reverse fault and vice versa.

Thrust faults form nappes and klippen in the large thrust belts. Subduction zones are a special class of thrusts that form the largest faults on Earth and give rise to the largest earthquakes.

Oblique-slip faults

A fault which has a component of dip-slip and a component of strike-slip is termed an oblique-slip fault. Nearly all faults have some component of both dip-slip and strike-slip; hence, defining a fault as oblique requires both dip and strike components to be measurable and significant. Some oblique faults occur within transtensional and transpressional regimes, and others occur where the direction of extension or shortening changes during the deformation but the earlier formed faults remain active.

The hade angle is defined as the complement of the dip angle; it is the angle between the fault plane and a vertical plane that strikes parallel to the fault.

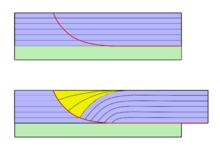

Listric fault

Listric faults are similar to normal faults but the fault plane curves, the dip being steeper near the surface, then shallower with increased depth. The dip may flatten into a sub-horizontal décollement, resulting in horizontal slip on a horizontal plane. The illustration shows slumping of the hanging wall along a listric fault. Where the hanging wall is absent (such as on a cliff) the footwall may slump in a manner that creates multiple listric faults.

Ring fault

Ring faults, also known as caldera faults, are faults that occur within collapsed volcanic calderas[13] and the sites of bolide strikes, such as the Chesapeake Bay impact crater. Ring faults are result of a series of overlapping normal faults, forming a circular outline. Fractures created by ring faults may be filled by ring dikes.[13]

Synthetic and antithetic faults

Synthetic and antithetic faults are terms used to describe minor faults associated with a major fault. Synthetic faults dip in the same direction as the major fault while the antithetic faults dip in the opposite direction. These faults may be accompanied by rollover anticlines (e.g. the Niger Delta Structural Style).

Fault rock

All faults have a measurable thickness, made up of deformed rock characteristic of the level in the crust where the faulting happened, of the rock types affected by the fault and of the presence and nature of any mineralising fluids. Fault rocks are classified by their textures and the implied mechanism of deformation. A fault that passes through different levels of the lithosphere will have many different types of fault rock developed along its surface. Continued dip-slip displacement tends to juxtapose fault rocks characteristic of different crustal levels, with varying degrees of overprinting. This effect is particularly clear in the case of detachment faults and major thrust faults.

The main types of fault rock include:

- Cataclasite – a fault rock which is cohesive with a poorly developed or absent planar fabric, or which is incohesive, characterised by generally angular clasts and rock fragments in a finer-grained matrix of similar composition.

- Tectonic or Fault breccia – a medium- to coarse-grained cataclasite containing >30% visible fragments.

- Fault gouge – an incohesive, clay-rich fine- to ultrafine-grained cataclasite, which may possess a planar fabric and containing <30% visible fragments. Rock clasts may be present

- Clay smear - clay-rich fault gouge formed in sedimentary sequences containing clay-rich layers which are strongly deformed and sheared into the fault gouge.

- Mylonite – a fault rock which is cohesive and characterized by a well-developed planar fabric resulting from tectonic reduction of grain size, and commonly containing rounded porphyroclasts and rock fragments of similar composition to minerals in the matrix

- Pseudotachylyte – ultrafine-grained glassy-looking material, usually black and flinty in appearance, occurring as thin planar veins, injection veins or as a matrix to pseudoconglomerates or breccias, which infills dilation fractures in the host rock. Pseudotachylyte likey only forms as the result of seismic slip rates, and can act as a fault rate indicator on inactive faults. [14]

Impacts on structures and people

In geotechnical engineering a fault often forms a discontinuity that may have a large influence on the mechanical behavior (strength, deformation, etc.) of soil and rock masses in, for example, tunnel, foundation, or slope construction.

The level of a fault's activity can be critical for (1) locating buildings, tanks, and pipelines and (2) assessing the seismic shaking and tsunami hazard to infrastructure and people in the vicinity. In California, for example, new building construction has been prohibited directly on or near faults that have moved within the Holocene Epoch (the last 11,700 years) of the Earth's geological history.[15] Also, faults that have shown movement during the Holocene plus Pleistocene Epochs (the last 2.6 million years) may receive consideration, especially for critical structures such as power plants, dams, hospitals, and schools. Geologists assess a fault's age by studying soil features seen in shallow excavations and geomorphology seen in aerial photographs. Subsurface clues include shears and their relationships to carbonate nodules, eroded clay, and iron oxide mineralization, in the case of older soil, and lack of such signs in the case of younger soil. Radiocarbon dating of organic material buried next to or over a fault shear is often critical in distinguishing active from inactive faults. From such relationships, paleoseismologists can estimate the sizes of past earthquakes over the past several hundred years, and develop rough projections of future fault activity.

Faults and ore deposits

Many ore deposits lie on faults. This is due to the fact that damaged fault zones allow for the circulation of mineral-bearing fluids. Intersections of near-vertical faults are often locations of significant ore deposits.[16]

An example of a fault hosting valuable porphyry copper deposits is northern Chile's Domeyko Fault with deposits at Chuquicamata, Collahuasi, El Abra, El Salvador, La Escondida and Potrerillos.[17] Further south in Chile Los Bronces and El Teniente porphyry copper deposit lie each at the intersection of two fault systems.[16]

See also

- Fault scarp – A small step or offset on the ground surface where one side of a fault has moved vertically with respect to the other

- Fault block

- Mitigation of seismic motion

- Mountain formation – The geological processes that underlie the formation of mountains

- Orogeny – The formation of mountain ranges

- Seismic hazard

- Striation – A groove, created by a geological process, on the surface of a rock or a mineral

- Vertical displacement - Vertical movement of Earth's crust

Notes

- Lutgens, Tarbuck, Tasa. Essentials of Geology (11th ed.). p. 32.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- USGS & Fault Traces

- USGS & Fault Lines.

- SCEC & Education Module, p. 14.

- "Faults: Introduction". University of California, Santa Cruz. Archived from the original on 2011-09-27. Retrieved 19 March 2010.

- USGS & Hanging Wall.

- Tingley & Pizarro 2000, p. 132

- Allaby 2015.

- Park 2004

- Peacock D.C.P.; Knipe R.J.; Sanderson D.J. (2000). "Glossary of normal faults". Journal of Structural Geology. 22 (3): 298. Bibcode:2000JSG....22..291P. doi:10.1016/S0191-8141(00)80102-9.

- "dip slip". Earthquake Glossary. USGS. Archived from the original on 23 November 2017. Retrieved 13 December 2017.

- "How are reverse faults different than thrust faults? In what way are they similar?". UCSB Science Line. University of California, Santa Barbara. 13 February 2012. Archived from the original on 27 October 2017. Retrieved 13 December 2017.

- "Structural Geology Notebook – Caldera Faults". maps.unomaha.edu. Archived from the original on 2018-11-19. Retrieved 2018-04-06.

- Rowe, Christie; Griffith, Ashley (2015). "Do faults preserve a record of seismic slip: A second opinion". Journal of Structural Geology. doi:10.1016/j.jsg.2015.06.006.

- Brodie et al. 2007

- Piquer Romo, José Meulen; Yáñez, Gonzálo; Rivera, Orlando; Cooke, David (2019). "Long-lived crustal damage zones associated with fault intersections in the high Andes of Central Chile". Andean Geology. 46 (2): 223–239. doi:10.5027/andgeoV46n2-3108 (inactive 2020-05-21). Archived from the original on August 8, 2019. Retrieved June 9, 2019.

- Robb, Laurence (2007). Introduction to Ore-Forming Processes (4th ed.). Malden, MA, United States: Blackwell Science Ltd. p. 104. ISBN 978-0-632-06378-9.

References

- Allaby, Michael, ed. (2015). "Strike-Slip Fault". A Dictionary of Geology and Earth Sciences (4th ed.). Oxford University Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Brodie, Kate; Fettes, Douglas; Harte, Ben; Schmid, Rolf (29 January 2007), Structural terms including fault rock terms, International Union of Geological Sciences

- Davis, George H.; Reynolds, Stephen J. (1996). "Folds". Structural Geology of Rocks and Regions (2nd ed.). John Wiley & Sons. pp. 372–424. ISBN 0-471-52621-5.

- Fichter, Lynn S.; Baedke, Steve J. (13 September 2000). "A Primer on Appalachian Structural Geology". James Madison University. Retrieved 19 March 2010.

- Hart, E.W.; Bryant, W.A. (1997). Fault rupture hazard in California: Alquist-Priolo earthquake fault zoning act with index to earthquake fault zone maps (Report). Special Publication 42. California Division of Mines and Geology.

- Marquis, John; Hafner, Katrin; Hauksson, Egill, "The Properties of Fault Slip", Investigating Earthquakes through Regional Seismicity, Southern California Earthquake Center, archived from the original on 25 June 2010, retrieved 19 March 2010

- McKnight, Tom L.; Hess, Darrel (2000). "The Internal Processes: Types of Faults". Physical Geography: A Landscape Appreciation. Prentice Hall. pp. 416–7. ISBN 0-13-020263-0.

- Park, R.G. (2004), Foundation of Structural Geology (3 ed.), Routledge, p. 11, ISBN 978-0-7487-5802-9

- Tingley, J.V.; Pizarro, K.A. (2000), Traveling America's loneliest road: a geologic and natural history tour, Nevada Bureau of Mines and Geology Special Publication, 26, Nevada Bureau of Mines and Geology, p. 132, ISBN 978-1-888035-05-6, retrieved 2010-04-02

- USGS, Hanging wall Foot wall, retrieved 2 April 2010

- USGS, Earthquake Glossary – fault trace, retrieved 10 April 2015

- USGS (30 April 2003), Where are the Fault Lines in the United States East of the Rocky Mountains?, archived from the original on 18 November 2009, retrieved 6 March 2010

External links

| The Wikibook Historical Geology has a page on the topic of: Faults |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Faults. |