Mongol invasions of Anatolia

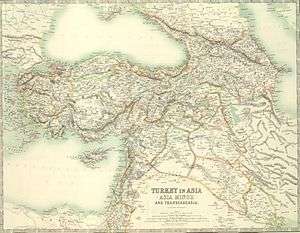

Mongol invasions of Anatolia occurred at various times, starting with the campaign of 1241–1243 that culminated in the Battle of Köse Dağ. Real power over Anatolia was exercised by the Mongols after the Seljuks surrendered in 1243 until the fall of the Ilkhanate in 1335.[1] Because the Seljuk Sultan rebelled several times, in 1255, the Mongols swept through central and eastern Anatolia. The Ilkhanate garrison was stationed near Ankara.[2][3] Timur's invasion is sometimes considered the last invasion of Anatolia by the Mongols.[4] Remains of the Mongol cultural heritage still can be seen in Turkey, including tombs of a Mongol governor and a son of Hulagu.

| Mongol invasions of Anatolia | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Mongol invasion of West Asia and Kublai Khan's Campaigns | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Anatolian Beyliks |

| ||||||

By the end of the 14th century, most of Anatolia was controlled by various Anatolian beyliks due to the collapse of the Seljuk dynasty in Rum. The Turkmen Beyliks were under the control of the Mongols through declining Seljuk Sultans.[5][6] The Beyliks did not mint coins in the names of their own leaders while they remained under the suzerainty of the Ilkhanids.[7] The Ottoman ruler Osman I was the first Turkish ruler who minted coins in his own name in the 1320s, for it bears the legend "Minted by Osman son of Ertuğrul".[8] Since the minting of coins was a prerogative accorded in Islamic practice only to be a sovereign, it can be considered that the Ottomans became independent of the Mongol Khans.[9]

Early relations

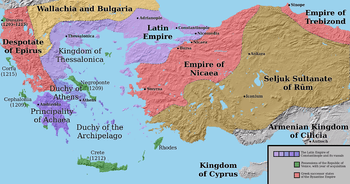

In the 12th century, the Byzantine Empire reasserted control in Western and Northern Anatolia. After the sack of Constantinople in 1204 by Latin Crusaders, two Byzantine successor states were established: the Empire of Nicaea, and the Despotate of Epirus. A third one, the Empire of Trebizond was created a few weeks before the sack of Constantinople by Alexios I of Trebizond. Of these three successor states, Trebizond and Nicaea stood near the Mongolian Empire. Control of Anatolia was then split between the Greek states and the Seljuk Sultanate of Rum, with the Byzantine holdings gradually being reduced.

The Mongol Empire conquered Persia in 1230; Chormaqan became military governor. There were then no hostilities with the Seljuk Turks. Kayqubad I and his immediate successor Kaykhusraw II swore an oath of vassalage with the payment of at least token tribute to the Great Khan Ögedei.[10][11] Ögedei died in 1241, and Kaykhusraw took the opportunity to repudiate his vassalage, believing he was strong enough to resist the Mongols. Chormaqan's successor Baiju summoned him to renew his submission: go to Mongolia in person, give hostages, and accept a Mongol darughachi. When the Sultan refused, Baiju declared war. The Seljuks invaded the Kingdom of Georgia, vassal of the Mongol Empire.

Fall of Erzurum

Part of a series on the |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| History of Turkey | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Baiju's army attacked Erzurum in relation to Kaykhusraw's disobedience in 1241. Before attacking, Baiju demanded submission. The inhabitants of the city insulted the Mhfghongol envoy sent by him. Since the city decided to resist and defied Mongol diplomacy, the Mongols besieged it. In two months, the Mongols took Karin and punished its residents. Aware of the Seljuk power in Anatolia, Baiju returned to the Mugan plain without advancing further.

Campaign in Erzurum

Baiju advanced to Erzurum with a contingent of Georgian and Armenian warriors under Avag and Shanshe in 1243. They besieged the city of Erzurum when its governor Yakut refused to surrender it. With the power of twelve catapults, Baiju stormed Erzurum. When the reports of the attack on Erzurum reported to him, Kaykhusraw summoned his armed forces at Konya. He accepted the challenge by sending a war message, defying Baiju that his army took only one of his many cities.

Köse Dağ

.jpeg)

The Seljuk Sultan made an alliance with all nations surrounding him. The King of Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia promised him to send a contingent; however, it is not certain they really engaged in his struggle with the Mongols. Kaykhusraw received the military support from the Empire of Trebizond and the Ayyubid Sultan at Aleppo, and the Frankish mercenaries participated in the campaign.[12] Because of little reliable information, it is difficult to measure the opposing troops. But the Seljuk force was larger than the Mongols.

Kaykhusraw advanced from Konya some 200 miles up to Köse Dağ. The Mongolian army entered the area in June 1243 and awaited the march of the Seljuks and their allies. The early stage of the battle was indecisive. The Sultan's forces suffered the greater casualties and he decided to withdraw at night. Pursuing him, Baiju received the submission of Erzinjan, Divrigi and Sivas en route.

The Mongols set up their camp near Sivas. When the Mongols penetrated into Kayseri, it chose to resist them. After a short resistance, it fell to the invaders. Hearing of the disaster at Köse Dağ, Hethum I of Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia quickly made his peace with the Mongols in 1243 and sent his brother Sembat to the Mongol court of Karakorum in 1247 to negotiate an alliance with the Mongolian Emperor Güyük.

Peace of Sivas

Kaykhusraw sent a delegation headed by his vizier to Baiju, realizing the further resistance would only produce a great disaster. Baiju offered terms based on resubmission and the Sultan was undertaken to pay a tribute tax every year in gold, silk, camel and sheep of uncertain quantities. However, the Turkish realm that had been taken by the military force remained occupied by the Mongols. Almost half of the Sultanate of Rum became an occupied country. The Empire of Trebizond became subject to the Mongolian Qaghan, fearing of the potential punitive expedition because they involved in the battle of Köse Dağ.[14]

In the Empire of Nicaea John III Doukas Vatatzes prepared for the coming Mongol threat. However, Vatatzes had sent envoys to the Qaghans Güyük and Möngke but was playing for time. The Mongol Empire did not cause any harm to his plan to recapture Constantinople from the hands of the Latins who also sent their envoy to the Mongols. Vatatzes' successors, the Palaiologan emperors of the restored Byzantine Empire, made an alliance with the Mongols, giving their princesses in marriage to the Mongol khans.

References

- Josef W. Meri, Jere L. Bacharach Medieval Islamic Civilization: A–K, index, p. 442

- H. M. Balyuzi Muḥammad and the course of Islám, p. 342

- John Freely Storm on Horseback: The Seljuk Warriors of Turkey, p. 83

- "A coalition of the willing, the friends of freedom?". Hürriyet Daily News. 27 January 2003. Retrieved 29 January 2015.

- Mehmet Fuat Köprülü, Gary Leiser The origins of the Ottoman empire, p. 33

- Peter Partner God of battles: holy wars of Christianity and Islam, p. 122

- Osman's Dream: The History of the Ottoman Empire, p. 13

- Artuk-Osmanli Beyliginin Kurucusu, 27f

- Pamuk A Monetary history, pp. 30–31

- D. S. Benson, The Mongol Campaigns in Asia, p. 177

- C. P. Atwood, Encyclopedia of Mongolia and the Mongol Empire, p. 555

- Claude Cahen, Pre-Ottoman Turkey: a general survey of the material and spiritual culture and history, trans. J. Jones-Williams, (New York: Taplinger, 1968) p. 137.

- Shepherd, William R. Historical Atlas, 1911.

- Peter Jackson, The Mongols and the West, p. 103