Septimius Severus

Lucius Septimius Severus (/səˈvɪərəs/ sə-VEER-əs;[5] Latin: [seˈweːrus]; 11 April 145 – 4 February 211) was Roman emperor from 193 to 211. He was born in Leptis Magna in the Roman province of Africa. As a young man he advanced through the customary succession of offices under the reigns of Marcus Aurelius and Commodus. Severus seized power after the death of Emperor Pertinax in 193 during the Year of the Five Emperors.

| Septimius Severus | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| Roman emperor | |||||

| Reign | 14 April 193 – 4 February 211 | ||||

| Predecessor | Didius Julianus | ||||

| Successor | Caracalla and Geta | ||||

| Co-emperors | |||||

| Born | Lucius Septimius Severus[1] 11 April 145[2] Leptis Magna | ||||

| Died | 4 February 211 (aged 65)[3] Eboracum | ||||

| Spouse |

| ||||

| Issue | Caracalla and Geta | ||||

| |||||

| Dynasty | Severan | ||||

| Father | Publius Septimius Geta | ||||

| Mother | Fulvia Pia | ||||

| Roman imperial dynasties | ||

|---|---|---|

| Severan dynasty | ||

| Chronology | ||

| 193–211 | ||

|

—with Caracalla 198–211 |

||

|

—with Geta 209–211 |

||

| 211 | ||

| 211–217 | ||

|

Interlude: Macrinus 217–218 |

||

|

—with Diadumenian 217–218 |

||

| 218–222 | ||

| 222–235 | ||

| Dynasty | ||

| Severan dynasty family tree | ||

|

All biographies |

||

| Succession | ||

|

After deposing and killing the incumbent emperor Didius Julianus, Severus fought his rival claimants, the Roman generals Pescennius Niger and Clodius Albinus. Niger was defeated in 194 at the Battle of Issus in Cilicia. Later that year Severus waged a short punitive campaign beyond the eastern frontier, annexing the Kingdom of Osroene as a new province. Severus defeated Albinus three years later at the Battle of Lugdunum in Gaul.

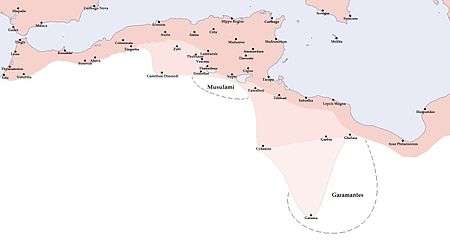

After consolidating his rule over the western provinces, Severus waged another brief, more successful war in the east against the Parthian Empire, sacking their capital Ctesiphon in 197 and expanding the eastern frontier to the Tigris. He then enlarged and fortified the Limes Arabicus in Arabia Petraea. In 202, he campaigned in Africa and Mauretania against the Garamantes, capturing their capital Garama and expanding the Limes Tripolitanus along the southern desert frontier of the empire. He proclaimed as Augusti (co-emperors) his elder son Caracalla in 198 and his younger son Geta in 209, both born of his second wife Julia Domna.

Severus travelled to Britain in 208, strengthening Hadrian's Wall and reoccupying the Antonine Wall. In AD 209 he invaded Caledonia (modern Scotland) with an army of 50,000 men[6] but his ambitions were cut short when he fell fatally ill of an infectious disease in late 210. He died in early 211 at Eboracum (today York, England), and was succeeded by his sons, thus founding the Severan dynasty. It was the last dynasty of the Roman Empire before the Crisis of the Third Century.

Early life

Family and education

Born on 11 April 145 at Leptis Magna (in present-day Libya) as the son of Publius Septimius Geta and Fulvia Pia,[2] Septimius Severus came from a wealthy and distinguished family of equestrian rank. He had Italian Roman ancestry on his mother's side, and was descended from Punic forebears on his father's side.[7]

Severus' father, an obscure provincial, held no major political status, but he had two cousins, Publius Septimius Aper and Gaius Septimius Severus, who served as consuls under the emperor Antoninus Pius r. 138–161. His mother's ancestors had moved from Italy to North Africa; they belonged to the gens Fulvia, an Italian patrician family that originated in Tusculum.[8] Septimius Severus had two siblings: an elder brother, Publius Septimius Geta; and a younger sister, Septimia Octavilla. Severus's maternal cousin was the praetorian prefect and consul Gaius Fulvius Plautianus.[9]

Septimius Severus grew up in Leptis Magna. He spoke the local Punic language fluently, but he was also educated in Latin and Greek, which he spoke with a slight accent. Little else is known of the young Severus' education but, according to Cassius Dio, the boy had been eager for more education than he actually received. Presumably Severus received lessons in oratory: at the age of 17 he gave his first public speech.[10]

Public service

Severus sought a public career in Rome in around 162. At the recommendation of his relative Gaius Septimius Severus, Emperor Marcus Aurelius (r. 161–180) granted him entry into the senatorial ranks.[12] Membership in the senatorial order was a prerequisite to attain positions within the cursus honorum and to gain entry into the Roman Senate. Nevertheless, it appears that Severus' career during the 160s met with some difficulties.[13] It is likely that he served as a vigintivir in Rome, overseeing road maintenance in or near the city, and he may have appeared in court as an advocate.[13] At the time of Marcus Aurelius he was the State Attorney (Advocatus fisci).[14] However, he omitted the military tribunate from the cursus honorum and had to delay his quaestorship until he had reached the required minimum age of 25.[13] To make matters worse, the Antonine Plague swept through the capital in 166.[15]

With his career at a halt, Severus decided to temporarily return to Leptis, where the climate was healthier.[15] According to the Historia Augusta, a usually unreliable source, he was prosecuted for adultery during this time but the case was ultimately dismissed. At the end of 169 Severus was of the required age to become a quaestor and journeyed back to Rome. On 5 December, he took office and was officially enrolled in the Roman Senate.[16] Between 170 and 180 his activities went largely unrecorded, in spite of the fact that he occupied an impressive number of posts in quick succession. The Antonine Plague had thinned the senatorial ranks and, with capable men now in short supply, Severus' career advanced more steadily than it otherwise might have.[17]

The sudden death of his father necessitated another return to Leptis Magna to settle family affairs. Before he was able to leave Africa, Mauri tribesmen invaded southern Spain. Control of the province was handed over to the Emperor, while the Senate gained temporary control of Sardinia as compensation. Thus, Septimius Severus spent the remainder of his second term as quaestor on the island of Sardinia.[18]

In 173, Severus' kinsman Gaius Septimius Severus was appointed proconsul of the Province of Africa. The elder Severus chose his cousin as one of his two legati pro praetore, a senior military appointment.[19] Following the end of this term, Septimius Severus returned to Rome, taking up office as tribune of the plebs, a senior legislative position, with the distinction of being the candidatus of the emperor.[20]

Marriages

About 175, Septimius Severus, in his early thirties at the time, contracted his first marriage, to Paccia Marciana, a woman from Leptis Magna.[21] He probably met her during his tenure as legate under his uncle. Marciana's name suggests Punic or Libyan origin, but nothing else is known of her. Septimius Severus does not mention her in his autobiography, though he commemorated her with statues when he became Emperor. The unreliable Historia Augusta claims that Marciana and Severus had two daughters, but no other attestation of them has survived. It appears that the marriage produced no surviving children, despite lasting for more than ten years.[20]

Marciana died of natural causes around 186.[22] Septimius Severus, now in his forties, childless and eager to remarry, began enquiring into the horoscopes of prospective brides. The Historia Augusta relates that he heard of a woman in Syria of whom it had been foretold that she would marry a king, and so Severus sought her as his wife.[21] This woman was an Emesan Syrian named Julia Domna. Her father, Julius Bassianus, descended from the Arab Emesan dynasty and served as a high priest to the local cult of the sun god Elagabal.[23] Domna's older sister, Julia Maesa, would become the grandmother of the future emperors Elagabalus and Alexander Severus.[24]

Bassianus accepted Severus' marriage proposal in early 187, and in the summer the couple married in Lugdunum (modern-day Lyon, France), of which Severus was the governor.[25] The marriage proved happy, and Severus cherished Julia and her political opinions. Julia built "the most splendid reputation" by applying herself to letters and philosophy.[26] They had two sons, Lucius Septimius Bassianus (later nicknamed Caracalla, born 4 April 188 in Lugdunum) and Publius Septimius Geta (born 7 March 189 in Rome).[27]

Rise to power

.jpg)

In 191, on the advice of Quintus Aemilius Laetus, prefect of the Praetorian Guard, Commodus appointed Severus as governor of Pannonia Superior.[28] Commodus was assassinated the following year. Pertinax was acclaimed emperor, but he was then killed by the Praetorian Guard in early 193. In response to the murder of Pertinax, Severus's legion XIV Gemina proclaimed him Emperor at Carnuntum. Nearby legions, such as X Gemina at Vindobona, soon followed suit. Having assembled an army, Severus hurried to Italy.[29]

Pertinax's successor in Rome, Didius Julianus, had bought the emperorship in an auction. Julianus was condemned to death by the Senate and killed.[30] Severus took possession of Rome without opposition. He executed Pertinax's murderers and dismissed the rest of the Praetorian Guard, filling its ranks with loyal troops from his own legions.[31][32]

The legions of Syria had proclaimed Pescennius Niger emperor. At the same time Severus felt it reasonable to offer Clodius Albinus, the powerful governor of Britannia, who had probably supported Didius against him, the rank of Caesar, which implied some claim to succession. With his rear safe, he moved to the East and crushed Niger's forces at the Battle of Issus (194).[32] While campaigning against Byzantium, he ordered that the tomb of his fellow-Carthaginian Hannibal be covered with fine marble.[33]

He devoted the following year to suppressing Mesopotamia and other Parthian vassals who had backed Niger. Afterwards Severus declared his son Caracalla as his successor, which caused Albinus to be hailed emperor by his troops and to invade Gallia. After a short stay in Rome, Severus moved north to meet him. On 19 February 197 at the Battle of Lugdunum, with an army of about 75,000 men, mostly composed of Pannonian, Moesian and Dacian legions and a large number of auxiliaries, Severus defeated and killed Clodius Albinus, securing his full control over the empire.[34][35][36]

Emperor

War against Parthia

In early 197 Severus departed Rome and travelled to the east by sea. He embarked at Brundisium and probably landed at the port of Aegeae in Cilicia,[37] travelling to Syria by land. He immediately gathered his army and crossed the Euphrates.[38] Abgar IX, titular King of Osroene but essentially only the ruler of Edessa since the annexation of his kingdom as a Roman province,[39] handed over his children as hostages and assisted Severus' expedition by providing archers.[40] King Khosrov I of Armenia also sent hostages, money and gifts.[41]

Severus traveled on to Nisibis, which his general Julius Laetus had prevented from falling into enemy hands. Afterwards Severus returned to Syria to plan a more ambitious campaign.[42] The following year he led another, more successful campaign against the Parthian Empire, reportedly in retaliation for the support it had given to Pescennius Niger. His legions sacked the Parthian royal city of Ctesiphon and he annexed the northern half of Mesopotamia to the empire,[43][44] taking the title Parthicus Maximus, following the example of Trajan.[45] However, he was unable to capture the fortress of Hatra even after two lengthy sieges, just like Trajan who had tried nearly a century before. During his time in the east, though, he also expanded the Limes Arabicus, building new fortifications in the Arabian Desert from Basie to Dumatha.[46]

Relations with the Senate and People

Severus' relations with the Senate were never good. He was unpopular with them from the outset, having seized power with the help of the military, and he returned the sentiment. Severus ordered the execution of a large number of Senators on charges of corruption or conspiracy against him and replaced them with his favourites. Although his actions turned Rome more into a military dictatorship, he was popular with the citizens of Rome, having stamped out the rampant corruption of Commodus's reign. When he returned from his victory over the Parthians, he erected the Arch of Septimius Severus in Rome.[47][48]

According to Cassius Dio,[49] however, after 197 Severus fell heavily under the influence of his Praetorian Prefect, Gaius Fulvius Plautianus, who came to have almost total control of the imperial administration. Plautianus's daughter, Fulvia Plautilla, was married to Severus's son, Caracalla. Plautianus's excessive power came to an end in 204, when he was denounced by the Emperor's dying brother. In January 205 Caracalla accused Plautianus of plotting to kill him and Severus. The powerful prefect was executed while he was trying to defend his case in front of the two emperors.[50] One of the two following praefecti was the famous jurist Papinian. Executions of senators did not stop: Cassius Dio records that many of them were put to death, some after being formally tried.[51]

Military reforms

.jpg)

Upon his arrival at Rome in 193, Severus discharged the Praetorian Guard,[31] which had murdered Pertinax and had then auctioned the Roman Empire to Didius Julianus. Its members were stripped of their ceremonial armour and forbidden to come within 160 kilometres (99 mi) miles of the city on pain of death.[52] Severus replaced the old guard with 10 new cohorts recruited from veterans of his Danubian legions.[53]

Around 197 he increased the number of legions from 30 to 33, with the introduction of the three new legions: I, II, and III Parthica.[54] He garrisoned Legio II Parthica at Albanum, only 20 kilometres (12 mi) from Rome.[53] He gave his soldiers a donative of a thousand sesterces (250 denarii) each,[55] and raised the annual wage for a soldier in the legions from 300 to 400 denarii.[56]

Severus was the first Roman emperor to station some of the imperial army in Italy. He realized that Rome needed a military central reserve with the capability to be sent anywhere.[57]

Reputed persecution of Christians

At the beginning of Severus' reign, Trajan's policy toward the Christians was still in force. That is, Christians were only to be punished if they refused to worship the emperor and the gods, but they were not to be sought out.[58] Therefore, persecution was inconsistent, local, and sporadic. Faced with internal dissidence and external threats, Severus felt the need to promote religious harmony by promoting syncretism.[59] He, possibly, issued an edict[60] that punished conversion to Judaism and Christianity.[61]

A number of persecutions of Christians occurred in the Roman Empire during his reign and are traditionally attributed to Severus by the early Christian community.[62] This is based on the decree mentioned in the Historia Augusta,[60] an unreliable mix of fact and fiction.[63] Early church historian Eusebius described Severus as a persecutor.[64] The Christian apologist Tertullian stated that Severus was well disposed towards Christians,[65] employed a Christian as his personal physician and had personally intervened to save several high-born Christians known to him from the mob.[63] Eusebius' description of Severus as a persecutor likely derives merely from the fact that numerous persecutions occurred during his reign, including those known in the Roman Martyrology as the martyrs of Madauros, Charalambos and Perpetua and Felicity in Roman-ruled Africa. These were probably the result of local persecutions rather than empire-wide actions or decrees by Severus.[66]

Military activity

Africa (202)

In late 202 Severus launched a campaign in the province of Africa. The legate of Legio III Augusta, Quintus Anicius Faustus, had been fighting against the Garamantes along the Limes Tripolitanus for five years. He captured several settlements such as Cydamus, Gholaia, Garbia, and their capital Garama – over 600 kilometres (370 mi) south of Leptis Magna.[67] The province of Numidia was also enlarged: the empire annexed the settlements of Vescera, Castellum Dimmidi, Gemellae, Thabudeos and Thubunae.[68] By 203 the entire southern frontier of Roman Africa had been dramatically expanded and re-fortified. Desert nomads could no longer safely raid the region's interior and escape back into the Sahara.[43]

Britain (208)

In 208 Severus travelled to Britain with the intention of conquering Caledonia. Modern archaeological discoveries illuminate the scope and direction of his northern campaign.[69] Severus probably arrived in Britain with an army over 40,000, considering some of the camps constructed during his campaign could house this number.[70]

He strengthened Hadrian's Wall and reconquered the Southern Uplands up to the Antonine Wall, which was also enhanced. Severus built a 165-acre (67 ha) camp south of the Antonine Wall at Trimontium, probably assembling his forces there.[71] Supported and supplied by a strong naval force,[72] Severus then thrust north with his army across the wall into Caledonian territory. Retracing the steps of Agricola of over a century before, Severus rebuilt and garrisoned many abandoned Roman forts along the east coast, such as Carpow.[73]

Around this time Severus' wife, Julia Domna, reportedly criticised the sexual morals of the Caledonian women. The wife of Caledonian chief Argentocoxos replied: "We fulfill the demands of nature in a much better way than do you Roman women; for we consort openly with the best men, whereas you let yourselves be debauched in secret by the vilest".[74]

Cassius Dio's account of the invasion reads:

Severus, accordingly, desiring to subjugate the whole of it, invaded Caledonia. But as he advanced through the country he experienced countless hardships in cutting down the forests, levelling the heights, filling up the swamps, and bridging the rivers; but he fought no battle and beheld no enemy in battle array. The enemy purposely put sheep and cattle in front of the soldiers for them to seize, in order that they might be lured on still further until they were worn out; for in fact the water caused great suffering to the Romans, and when they became scattered, they would be attacked. Then, unable to walk, they would be slain by their own men, in order to avoid capture, so that a full fifty thousand died. But Severus did not desist until he approached the extremity of the island. Here he observed most accurately the variation of the sun's motion and the length of the days and the nights in summer and winter respectively. Having thus been conveyed through practically the whole of the hostile country (for he actually was conveyed in a covered litter most of the way, on account of his infirmity), he returned to the friendly portion, after he had forced the Britons to come to terms, on the condition that they should abandon a large part of their territory.[75]

By 210 Severus' campaigning had made significant gains, despite Caledonian guerrilla tactics and purportedly heavy Roman casualties.[76] The Caledonians sued for peace, which Severus granted on condition they relinquish control of the Central Lowlands.[69][77] This is evidenced by extensive Severan-era fortifications in the Central Lowlands.[78] The Caledonians, short on supplies and feeling that their position was desperate, revolted later that year with the Maeatae.[79] Severus prepared for another protracted campaign within Caledonia. He was now intent on exterminating the Caledonians, telling his soldiers: "Let no-one escape sheer destruction, no-one our hands, not even the babe in the womb of the mother, if it be male; let it nevertheless not escape sheer destruction."[80][72]

Death (211)

Severus' campaign was cut short when he fell ill.[81][82] He withdrew to Eboracum (York) and died there in 211.[3] Although his son Caracalla continued campaigning the following year, he soon settled for peace. The Romans never campaigned deep into Caledonia again. Shortly after this the frontier was permanently withdrawn south to Hadrian's Wall.[83]

Severus is famously said to have given the advice to his sons: "Be harmonious, enrich the soldiers, scorn all others" before he died on 4 February 211.[84] On his death, Severus was deified by the Senate and succeeded by his sons, Caracalla and Geta, who were advised by his wife Julia Domna.[85] Severus was buried in the Mausoleum of Hadrian in Rome. His remains are now lost.[86]

Assessment and legacy

Though his military expenditure was costly to the empire, Severus was a strong and able ruler. The Roman Empire reached its greatest extent under his reign – over 5 million square kilometres.[87][88]

According to Gibbon, "his daring ambition was never diverted from its steady course by the allurements of pleasure, the apprehension of danger, or the feelings of humanity."[89] His enlargement of the Limes Tripolitanus secured Africa, the agricultural base of the empire where he was born.[90] His victory over the Parthian Empire was for a time decisive, securing Nisibis and Singara for the empire and establishing a status quo of Roman dominance in the region until 251.[91] His policy of an expanded and better-rewarded army was criticised by his contemporaries Cassius Dio and Herodianus: in particular, they pointed out the increasing burden, in the form of taxes and services, the civilian population had to bear to maintain the new and better paid army.[92][93] The large and ongoing increase in military expenditure caused problems for all of his successors.[88]

To maintain his enlarged military, he debased the Roman currency. Upon his accession he decreased the silver purity of the denarius from 81.5% to 78.5%, although the silver weight actually increased, rising from 2.40 grams to 2.46 grams. Nevertheless, the following year he debased the denarius again because of rising military expenditures. The silver purity decreased from 78.5% to 64.5% – the silver weight dropping from 2.46 grams to 1.98 grams. In 196 he reduced the purity and silver weight of the denarius again, to 54% and 1.82 grams respectively.[94] Severus' currency debasement was the largest since the reign of Nero, compromising the long-term strength of the economy.[95]

Severus was also distinguished for his buildings. Apart from the triumphal arch in the Roman Forum carrying his full name, he also built the Septizodium in Rome. He enriched his native city of Leptis Magna, including commissioning a triumphal arch on the occasion of his visit of 203. The greater part of the Flavian Palace overlooking the Circus Maximus was undertaken in his reign.[96][48]

See also

- Bulla Felix

- Septimia (gens)

- Arcus Argentariorum dedicated by the money changers of Rome to the Severan family.

References

- Cooley, Alison E. (2012). The Cambridge Manual of Latin Epigraphy. Cambridge University Press. p. 495. ISBN 978-0-521-84026-2.

- Birley (1999), p. 1.

- Birley (1999), p. 187.

- Cooley, Alison E. (2012). The Cambridge Manual of Latin Epigraphy. Cambridge University Press. p. 495. ISBN 978-0-521-84026-2.

- "Severus". The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (5th ed.). Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Retrieved 6 November 2019.

- Elliott, Simon (2018). Septimius Severus in Scotland: The Northern Campaigns of the First Hammer of the Scots. Greenhill Books. p. 147. ISBN 978-1-78438-204-9.

- Birley (1999), pp. 212–213.

- Adam, Alexander, Classical biography,Google eBook Archived 10 June 2016 at the Wayback Machine, p.182: FULVIUS, the name of a "gens" which originally came from Tusculum (Cic. Planc. 8).

- Birley (1999), pp. 216–217.

- Birley (1999), pp. 34–35.

- Mattingly & Sydenham, Roman Imperial Coinage, vol. IV, part I, p. 115.

- Birley (1999), p. 39.

- Birley (1999), p. 40.

- Smith, Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology, London 1870, v. 3, pg. 117.

- Birley (1999), p. 45.

- Birley (1999), p. 46.

- Birley (1999), p. 49.

- Birley (1999), p. 50.

- Birley (1999), p. 51.

- Birley (1999), p. 52.

- Birley (1999), p. 71.

- Birley (1999), p. 75.

- Birley (1999), p. 72.

- Cassius Dio, Roman History LXXIX.30 Archived 26 May 2012 at Archive.today

- Birley (1999), pp. 76–77; Fishwick (2005), p. 347.

- Gibbon (1831), p. 74.

- Birley (1999), pp. 76–77.

- Bunson, Matthew (2002). Encyclopedia of the Roman Empire. Roma: Newton & Compton. p. 300. ISBN 9788882896270.

- Campbell 1994, pp. 40–41.

- Cassius Dio, Roman History, LXXIV.17.4

- Cassius Dio, Roman History, LXXV.1.1–2

- Birley (1999), p. 113.

- Gabriel, Richard A. Hannibal: The Military Biography of Rome's Greatest Enemy, Potomac Books, Inc., 2011 ISBN 1-59797-766-7, Google books

- Spartianus, Severus 11

- 1889–1943., Collingwood, R. G. (Robin George) (1998) [1936]. Roman Britain and the English settlements. Myres, J. N. L. (John Nowell Linton). [New York, N.Y.]: Biblo and Tannen. ISBN 978-0819611604. OCLC 36750306.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- Birley (1999), p. 125.

- Hasebroek (1921), p. 111.

- "Life of Septimius Severus" in Historia Augusta, 16.1.

- Birley (1999), p. 115.

- Birley (1999), p. 129.

- Hovannisian, The Armenian People From Ancient to Modern Times, Volume I: The Dynastic Periods: From Antiquity to the Fourteenth Century, p.71

- Prosopographia Imperii Romani L 69.

- Birley (1999), p. 153.

- Birley (1999), p. 130.

-

- Kröger, Jens (1993). "Ctesiphon". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. IV, Fasc. 4. pp. 446–448.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Birley (1999), p. 134.

- Asante, Molefi Kete and Shanza Ismail, “Rediscovering the ‘Lost’Roman Caesar: Septimius Severus the African and Eurocentric Historiography.” Journal of Black Studies 40, no. 4 (March 2010): 606–618

- Perkins, J. B. Ward (December 1951). "The Arch of Septimius Severus at Lepcis Magna". Archaeology. 4 (4): 226–231.

- Cassius Dio, Roman History, Book 76, Sections 14 and 15.

- Birley (1999), pp. 161–162.

- Birley (1999), p.165.

- Birley (1999), p. 103.

- Lesley Adkins and Roy A. Adkins, Both Professional Handbook to Life in Ancient Rome, p. 68

- George Ronald Watson, The Roman Soldier, p.23

- "Septimius Severus: Legionary Denarius". penelope.uchicago.edu.

- Kenneth W. Harl, Coinage in the Roman Economy, 300 B.C. to A.D. 700, Part 700, p.216

- Michael Grant(1978); History of Rome; p.358;Charles Scribner's Sons; NY

- González 2010, p. 97.

- González 2010, pp. 97–98.

- Historia Augusta, Septimius Severus, 17.1

- Tabbernee 2007, pp. 182–183.

- Tabbernee 2007, p. 182.

- Tabbernee 2007, p. 184.

- Eusebius, Historia Ecclesiastica, VI.1.1

- (in Latin) Tertullian, Ad Scapulam Archived 25 October 2015 at the Wayback Machine, IV.5–6

- Tabbernee 2007, p. 185.

- Birley (1999), p. 153.

- Birley (1999), p. 147.

- Birley, (1999) p. 180.

- W.S. Hanson "Roman campaigns north of the Forth-Clyde isthmus: the evidence of the temporary camps" Archived 7 November 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- Birley (1999), pp. 180–181.

- Smith, Laura (16 May 2018). "The Honest Truth: How the Romans came close but ultimately failed to conquer Scotland under Septimius Severus". The Sunday Post. Archived from the original on 21 May 2018. Retrieved 21 May 2018.

- "Carpow | Canmore". canmore.org.uk. Archived from the original on 16 May 2018. Retrieved 15 May 2018.

- Cassius Dio "Roman History: Epitome of Book LXXVII" University of Chicago. Retrieved 24 July 2008.

- "Cassius Dio — Epitome of Book 77". Penelope.uchicago.edu. Retrieved 7 November 2012.

- Keys, David (27 June 2018). "Ancient Roman 'hand of god' discovered near Hadrian's Wall sheds light on biggest combat operation ever in UK". Independent. Archived from the original on 7 July 2018. Retrieved 6 July 2018.

- Cassius Dio, Roman History: Epitome of Book LXXVII.13.

- Birley (1999) pp. 180–82.

- Birley (1999) p. 186.

- Dio Cassius (Xiphilinus) 'Romaika' Epitome of Book LXXVI Chapter 15.

- Cassius Dio, Roman History, Book 77, Sections 11–15.

- Birley (1999), pp. 170–187.

- Birley (1999), pp. 170–187.

- Cassius Dio, Roman History, Book 77, Section 15.

- "Life of Septimius Severus" in Historia Augusta, Section 19.

- "Preface, "Lives of the Artists"". Archived from the original on 10 December 2010. Retrieved 13 May 2018.

- David L. Kennedy, Derrick Riley (2012), Rome's Desert Frontiers, page 13 Archived 30 July 2017 at the Wayback Machine, Routledge

- R.J. van der Spek, Lukas De Blois (2008), An Introduction to the Ancient World, page 272 Archived 30 July 2017 at the Wayback Machine, Routledge

- Gibbon, Edward (1776). The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. London: Cadell. p. 96. OCLC 840075577. Archived from the original on 19 February 2016. Retrieved 25 December 2015.

- Kenneth D. Matthews, Jr., Cities in the Sand. The Roman Background of Tripolitania, 1957

- Erdkamp, Paul (2011). A Companion to the Roman Army. Malden (Massachusetts): Blackwell. p. 251. ISBN 9781444339215.

- Cassius Dio, Roman History LXXV.2.3

- Herodianus, History of the Roman Empire Archived 24 November 2009 at the Wayback Machine III.9.2–3

- "Tulane University "Roman Currency of the Principate"". Archived from the original on 10 February 2001. Retrieved 3 March 2011.

- Kenneth W. Harl, Coinage in the Roman Economy, 300 B.C. to A.D. 700, Part 700, p.126

- Gregorovius, Ferdinand (1895). History of the city of Rome in the Middle Ages. 3. Cambridge University Press. p. 541. OCLC 57224029.

References

- Birley, Anthony R. (1999) [1971]. Septimius Severus: The African Emperor. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0415165914.

- Elliott, Simon (2018). Septimius Severus in Scotland: The Northern Campaigns of the First Hammer of the Scots. London: Greenhill Books. ISBN 978-1784382049.[1]

- Grant, Michael (1985). The Roman Emperors. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 978-0760700914.

- Grant, Michael (1996). The Severans: The Changed Roman Empire. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0415127721.

- Settipani, Christian (2000). Continuité Gentilice et Continuité Familiale dans les Familles Sénatoriales Romaines à l'Époque Impériale: Mythe et Réalité. Oxford: Unit for Prosographical Research, Linacre College, University of Oxford. ISBN 9781900934022.

- Daguet-Gagey, Anne (2000). Septime Sévère: Rome, l'Afrique et l'Orient. Biographie Payot (in French). Paris: Payot. ISBN 9782228893367.

- Cooley, Alison (2007). "Septimius Severus: The Augustan Emperor". In Swain, Simon; Harrison, Stephen; Elsner, Jas (eds.). Severan Culture. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521859820.

- Fishwick, Duncan (2005). The Imperial Cult in the Latin West: Studies in the Ruler Cult of the Western Provinces of the Roman Empire. E.J. Brill.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gibbon, Edward (1831). The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. New York.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hasebroek, Johannes (1921). Untersuchungen zur Geschichte des Kaisers Septimius Severus. Heidelberg: C Winter. OCLC 4153259.

- Hovannisian, R.G. (2004) [1997]. The Armenian People From Ancient to Modern Times. 1: The Dynastic Periods: From Antiquity to the Fourteenth Century. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 9781403964212.

- Lichtenberger, Achim (2011). Severus Pius Augustus: Studien zur sakralen Repräsentation und Rezeption der Herrschaft des Septimius Severus und seiner Familie (193–211 n. chr.). Impact of Empire. 14. Leiden; Boston: Brill. ISBN 9789004201927.

- González, Justo L. (2010). The Story of Christianity: The Early Church to the Dawn of the Reformation. 1. New York: HarperCollins. ISBN 9780061855887. OCLC 905489146.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mattingly, Harold & Edward A. Sydenham (1936) The Roman Imperial Coinage, vol. IV, part I, Pertinax to Geta, London, Spink & Son.

- Tabbernee, William (2007). Fake Prophecy and Polluted Sacraments: Ecclesiastical and Imperial Reactions to Montanism (Supplements to Vigiliae Christianae). Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-9004158191.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Campbell, Brian (1994). The Roman Army, 31 BC - AD 337: A Sourcebook. London: Routledge. ISBN 9780415071727.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Septimius Severus |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Septimius Severus. |

- Life of Septimius Severus (Historia Augusta at LacusCurtius: Latin text and English translation)

- Books 74, 75, 76, and 77 of Dio Cassius, covering the rise to power and reign of Septimius Severus

- Septimius Severus on Ancient History Encyclopedia

- Book 3 of Herodian

- De Imperatoribus Romanis Online encyclopaedia of Roman Emperors

- Arch of Septimius Severus in Rome

- Septimius Severus in Scotland

- Arch of Septimius Severus in Lepcis Magna

- Coins issued by Septimius Severus

- Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- THE LIFE AND REIGN OF THE EMPEROR LUCIUS SEPTIMIUS SEVERUS, in BTM Format

Septimius Severus Born: 11 April 146 Died: 4 February 211 | ||

| Regnal titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Didius Julianus |

Roman Emperor 193–211 with Pescennius Niger (rival 193–194), Clodius Albinus (rival 193–197), Caracalla (198–211), Publius Septimius Geta (209–211) |

Succeeded by Caracalla, Publius Septimius Geta |

| Political offices | ||

| Preceded by Lucius Fabius Cilo, and Marcus Silius Messala |

Consul of the Roman Empire 194 with Clodius Albinus |

Succeeded by Publius Julius Scapula Tertullus Priscus, and Quintus Tineius Clemens |

| Preceded by Annius Fabianus, and Marcus Nonius Arrius Mucianus |

Consul of the Roman Empire 202 with Caracalla |

Succeeded by Titus Murrenius Severus, and Gaius Cassius Regallianus as Suffect consuls |