History of Wales

The history of Wales begins with the arrival of human beings in the region thousands of years ago. Neanderthals lived in what is now Wales, or Cymru to the Welsh people, at least 230,000 years ago,[1] while Homo sapiens arrived by about 31,000 BC.[2] However, continuous habitation by modern humans dates from the period after the end of the last ice age around 9000 BC, and Wales has many remains from the Mesolithic, Neolithic, and Bronze Age. During the Iron Age the region, like all of Britain south of the Firth of Forth, was dominated by the Celtic Britons and the Brittonic language.[3] The Romans, who began their conquest of Britain in AD 43, first campaigned in what is now northeast Wales in 48 against the Deceangli, and gained total control of the region with their defeat of the Ordovices in 79. The Romans departed from Britain in the 5th century, opening the door for the Anglo-Saxon invasion. Thereafter Brittonic language and culture began to splinter, and several distinct groups formed. The Welsh people were the largest of these groups, and are generally discussed independently of the other surviving Brittonic-speaking peoples after the 11th century.[3]

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Wales |

|

|

Chronology |

|

|

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Wales |

|---|

.svg.png) |

| History |

| People |

|

|

Traditions

|

|

Mythology and folklore |

|

Festivals |

| Religion |

| Art |

|

Literature

|

|

Music and performing arts |

|

Monuments

|

|

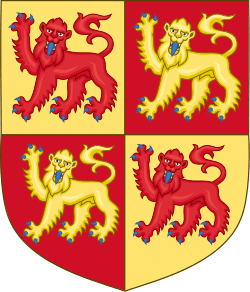

A number of kingdoms formed in present-day Wales in the post-Roman period. While the most powerful ruler was acknowledged as King of the Britons (later Tywysog Cymru: Leader or Prince of Wales), and some rulers extended their control over other Welsh territories and into western England, none were able to unite Wales for long. Internecine struggles and external pressure from the English and later, the Norman conquerors of England, led to the Welsh kingdoms coming gradually under the sway of the English crown. In 1282, the death of Llywelyn ap Gruffudd led to the conquest of the Principality of Wales by King Edward I of England; afterwards, the heir apparent to the English monarch has borne the title "Prince of Wales". The Welsh launched several revolts against English rule, the last significant one being that led by Owain Glyndŵr in the early 15th century. In the 16th century Henry VIII, himself of Welsh extraction as a great grandson of Owen Tudor, passed the Laws in Wales Acts aiming to fully incorporate Wales into the Kingdom of England. Under England's authority, Wales became part of the Kingdom of Great Britain in 1707 and then the United Kingdom in 1801. Yet, the Welsh retained their language and culture despite heavy English dominance. The publication of the extremely significant first complete Welsh translation of the Bible by William Morgan in 1588 greatly advanced the position of Welsh as a literary language.[4]

The 18th century saw the beginnings of two changes that would greatly affect Wales, the Welsh Methodist revival, which led the country to turn increasingly nonconformist in religion, and the Industrial Revolution. During the rise of the British Empire, 19th century Southeast Wales in particular experienced rapid industrialisation and a dramatic rise in population as a result of the explosion of the coal and iron industries.[5] Wales played a full and willing role in World War One. The industries of Empire in Wales declined in the 20th century with the end of the British Empire following the Second World War, while nationalist sentiment and interest in self-determination rose. The Labour Party replaced the Liberal Party as the dominant political force in the 1920s. Wales played a considerable role during World War Two along with the rest of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland and the Allies, and its cities were bombed extensively during the Nazi Blitz. The nationalist party Plaid Cymru gained momentum from the 1960s. In a 1997 referendum Welsh voters approved the devolution of governmental responsibility to a National Assembly for Wales (now known as the Senedd or Welsh Parliament), which first met in 1999.

Prehistoric Wales

The earliest known human remain discovered in modern-day Wales is a Neanderthal jawbone, found at the Bontnewydd Palaeolithic site in the valley of the River Elwy in North Wales, whose owner lived about 230,000 years ago in the Lower Palaeolithic period.[6][7] The Red Lady of Paviland, a human skeleton dyed in red ochre, was discovered in 1823 in one of the Paviland limestone caves of the Gower Peninsula in Swansea, South Wales. Despite the name, the skeleton is that of a young man who lived about 33,000 years ago at the end of the Upper Paleolithic Period (old Stone Age).[2] It is considered to be the oldest known ceremonial burial in Western Europe. The skeleton was found along with jewellery made from ivory and seashells and a mammoth's skull.

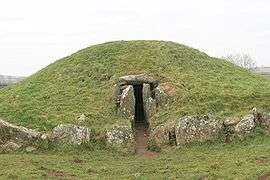

Following the last ice age, Wales became roughly the shape it is today by about 8000 BC and was inhabited by Mesolithic hunter-gatherers. The earliest farming communities are now believed to date from about 4000 BC, marking the beginning of the Neolithic period. This period saw the construction of many chambered tombs particularly dolmens or cromlechs. The most notable examples of megalithic tombs include Bryn Celli Ddu and Barclodiad y Gawres on Anglesey,[8] Pentre Ifan in Pembrokeshire, and Tinkinswood Burial Chamber in the Vale of Glamorgan.[9]

Metal tools first appeared in Wales about 2500 BC, initially copper followed by bronze. The climate during the Early Bronze Age (c. 2500–1400 BC) is thought to have been warmer than at present, as there are many remains from this period in what are now bleak uplands. The Late Bronze Age (c. 1400–750 BC) saw the development of more advanced bronze implements. Much of the copper for the production of bronze probably came from the copper mine on the Great Orme, where prehistoric mining on a very large scale dates largely from the middle Bronze Age.[10] Radiocarbon dating has shown the earliest hillforts in what would become Wales, to have been constructed during this period. Historian John Davies, theorises that a worsening climate after around 1250 BC (lower temperatures and heavier rainfall) required more productive land to be defended.[11]

The earliest iron implement found in Wales is a sword from Llyn Fawr which overlooks the head of the Vale of Neath, which is thought to date to about 600 BC.[12] Hillforts continued to be built during the British Iron Age. Nearly 600 hillforts are in Wales, over 20% of those found in Britain, examples being Pen Dinas near Aberystwyth and Tre'r Ceiri on the Llŷn peninsula.[11] A particularly significant find from this period was made in 1943 at Llyn Cerrig Bach on Anglesey, when the ground was being prepared for the construction of a Royal Air Force base. The cache included weapons, shields, chariots along with their fittings and harnesses, and slave chains and tools. Many had been deliberately broken and seem to have been votive offerings.[13]

Until recently, the prehistory of Wales was portrayed as a series of successive migrations.[4] The present tendency is to stress population continuity; the Encyclopedia of Wales suggests that Wales had received the greater part of its original stock of peoples by c.2000 BC.[4] Recent studies in population genetics have argued for genetic continuity from the Upper Paleolithic, Mesolithic or Neolithic eras.[14][15] According to historian John Davies, the Brythonic languages spoken throughout Britain resulted from an indigenous "cumulative Celticity", rather than from migration.[11]

Wales in the Roman era

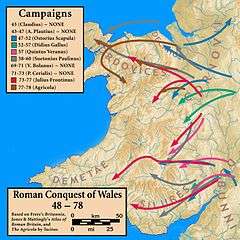

The Roman conquest of Wales began in AD 48 and was completed in 78, with Roman rule lasting until 383. Roman rule in Wales was a military occupation, save for the southern coastal region of South Wales east of the Gower Peninsula, where there is a legacy of Romanisation.[16] The only town in Wales founded by the Romans, Caerwent, is located in South Wales. Both Caerwent and Carmarthen, also in southern Wales, would become Roman civitates.[17] During the occupation both the region that would become Wales and its people were a mostly autonomous part of Roman Britain.

By AD 47 Rome had invaded and conquered all of southernmost and southeastern Britain under the first Roman governor of Britain. As part of the Roman conquest of Britain, a series of campaigns to conquer Wales was launched by his successor in 48 and would continue intermittently under successive governors until the conquest was completed in 78. It is these campaigns of conquest that are the most widely known feature of Wales during the Roman era due to the spirited but unsuccessful defence of their homelands by two native tribes, the Silures and the Ordovices.

The Demetae of southwestern Wales seem to have quickly made their peace with the Romans, as there is no indication of war with Rome, and their homeland was not heavily planted with forts nor overlaid with roads. The Demetae would be the only Welsh tribe to emerge from Roman rule with their homeland and tribal name intact.[18]

Wales was a rich source of mineral wealth and the Romans used their engineering technology to extract large amounts of gold, copper, and lead, as well as modest amounts of some other metals such as zinc and silver.[19] When the mines were no longer practical or profitable, they were abandoned. Roman economic development was concentrated in southeastern Britain, with no significant industries located in Wales.[19] This was largely a matter of circumstance, as Wales had none of the needed materials in suitable combination, and the forested, mountainous countryside was not amenable to development.

The year 383 denotes a significant point in Welsh history, remembered in literature and considered to be the foundation point of several medieval royal dynasties. In that year the Roman general Magnus Maximus would strip all of western and northern Britain of troops and senior administrators and launch a partly successful bid for imperial power, continuing to rule Britain from Gaul as emperor.[20][21] Having left with the troops and Roman administrators, and planning to continue as the ruler of Britain in the future, his practical course was to transfer local authority to local rulers. Welsh legend provides a mythic background to this process.

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

In the story of Breuddwyd Macsen Wledig (English: The Dream of Emperor Maximus), he is Emperor of Rome and marries a wondrous British woman, telling her that she may name her desires, to be received as a wedding portion. She asks that her father be given sovereignty over Britain, thus formalising the transfer of authority from Rome back to the Britons themselves. The marriage also makes possible British descendants, a point not lost on medieval kings. The earliest Welsh genealogies give Maximus the role of founding father for several royal dynasties, including those of Powys and Gwent,[22][23] a role he also played for the rulers of medieval Galloway in Scotland, home to the Roman-era Novantae whose territory was also made independent of Roman rule by Maximus.[20] He is given as the ancestor of a Welsh king on the Pillar of Eliseg, erected nearly 500 years after he left Britain, and he figures in lists of the Fifteen Tribes of Wales.[24]

Tradition holds that following the Roman departure, Roman customs held on into the 5th century in southern Wales, and that is true in part. Caerwent continued to be occupied, while Carmarthen was probably abandoned in the late 4th century.[25] In addition, southwestern Wales was the tribal territory of the Demetae, who had never become thoroughly Romanised.[16] An influx of settlers from southeastern Ireland had taken place in the late 4th century,[26] both in northern Wales and in the entire region of southern and southwestern Wales[27][28][29] under circumstances that are still poorly understood, and it seems far-fetched to suggest that they were ever Romanised.

Indeed, aside from the many Roman-related finds along the southern coast and the fully romanised area around Caerwent, Roman archaeological remains in Wales consist almost entirely of military roads and fortifications.[30]

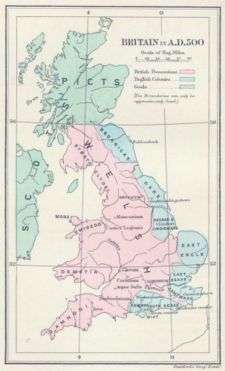

Post-Roman Wales and the Age of the Saints: 411–700

When the Roman garrison of Britain was withdrawn in 410, the various British states were left self-governing. Evidence for a continuing Roman influence after the departure of the Roman legions is provided by an inscribed stone from Gwynedd dated between the late 5th century and mid 6th century commemorating a certain Cantiorix who was described as a citizen (cives) of Gwynedd and a cousin of Maglos the magistrate (magistratus).[31] There was considerable Irish colonisation in Dyfed in south-west Wales, where there are many stones with Ogham inscriptions.[32] Wales had become Christian, and the "age of the saints" (approximately 500–700) was marked by the establishment of monastic settlements throughout the country, by religious leaders such as Saint David, Illtud and Teilo.[33]

One of the reasons for the Roman withdrawal was the pressure put upon the empire's military resources by the incursion of barbarian tribes from the east. These tribes, including the Angles and Saxons, who later became the English, were unable to make inroads into Wales except possibly along the Severn Valley as far as Llanidloes.[34] However, they gradually conquered eastern and southern Britain. At the Battle of Chester in 616, the forces of Powys and other British kingdoms were defeated by the Northumbrians under Æthelfrith, with king Selyf ap Cynan among the dead. It has been suggested that this battle finally severed the land connection between Wales and the kingdoms of the Hen Ogledd ("Old North"), the Brythonic-speaking regions of what is now southern Scotland and northern England, including Rheged, Strathclyde, Elmet and Gododdin, where Old Welsh was also spoken.[35] From the 8th century on, Wales was by far the largest of the three remnant Brythonic areas in Britain, the other two being the Hen Ogledd and Cornwall.

Wales was divided into a number of separate kingdoms, the largest of these being Gwynedd in northwest Wales and Powys in east Wales. Gwynedd was the most powerful of these kingdoms in the 6th century and 7th century, under rulers such as Maelgwn Gwynedd (died 547)[36] and Cadwallon ap Cadfan (died 634/5),[37] who in alliance with Penda of Mercia was able to lead his armies as far as Northumbria in 633,[38] defeat the local ruler Edwin and control it for approximately one year. When Cadwallon was killed in battle by Oswald of Northumbria, his successor Cadafael ap Cynfeddw also allied himself with Penda against Northumbria, but thereafter Gwynedd, like the other Welsh kingdoms, was mainly engaged in defensive warfare against the growing power of Mercia.

Early Medieval Wales: 700–1066

Powys as the easternmost of the major kingdoms of Wales came under the most pressure from the English in Cheshire, Shropshire and Herefordshire. This kingdom originally extended east into areas now in England, and its ancient capital, Pengwern, has been variously identified as modern Shrewsbury or a site north of Baschurch.[39] These areas were lost to the kingdom of Mercia. The construction of the earthwork known as Offa's Dyke (usually attributed to Offa, King of Mercia in the 8th century) may have marked an agreed border.[40]

For a single man to rule the whole country during this period was rare. This is often ascribed to the inheritance system practised in Wales. All sons received an equal share of their father's property (including illegitimate sons), resulting in the division of territories. However, the Welsh laws prescribe this system of division for land in general, not for kingdoms, where there is provision for an edling (or heir) to the kingdom to be chosen, usually by the king. Any son, legitimate or illegitimate, could be chosen as edling and there were frequently disappointed candidates prepared to challenge the chosen heir.[41]

_King_Hywel_cropped.jpg)

The first to rule a considerable part of Wales was Rhodri Mawr (Rhodri The Great), originally king of Gwynedd during the 9th century, who was able to extend his rule to Powys and Ceredigion.[42] On his death his realms were divided between his sons. Rhodri's grandson, Hywel Dda (Hywel the Good), formed the kingdom of Deheubarth by joining smaller kingdoms in the southwest and had extended his rule to most of Wales by 942.[43] He is traditionally associated with the codification of Welsh law at a council which he called at Whitland, the laws from then on usually being called the "Laws of Hywel". Hywel followed a policy of peace with the English. On his death in 949 his sons were able to keep control of Deheubarth but lost Gwynedd to the traditional dynasty of this kingdom.[44]

Wales was now coming under increasing attack by Viking raiders, particularly Danish raids in the period between 950 and 1000. According to the chronicle Brut y Tywysogion, Godfrey Haroldson carried off two thousand captives from Anglesey in 987, and the king of Gwynedd, Maredudd ab Owain is reported to have redeemed many of his subjects from slavery by paying the Danes a large ransom.[45]

Gruffydd ap Llywelyn was the only ruler to be able to unite Wales under his rule. Originally king of Gwynedd, by 1057 he was ruler of Wales and had annexed parts of England around the border. He ruled Wales with no internal battles[46] until he was defeated by Harold Godwinson in 1063 and killed by his own men. His territories were again divided into the traditional kingdoms.[47]

Wales and the Normans: 1067–1283

At the time of the Norman conquest of England in 1066, the dominant ruler in Wales was Bleddyn ap Cynfyn, who was king of Gwynedd and Powys. The initial Norman successes were in the south, where William Fitz Osbern overran Gwent before 1070. By 1074 the forces of the Earl of Shrewsbury were ravaging Deheubarth.[48]

The killing of Bleddyn ap Cynfyn in 1075 led to civil war and gave the Normans an opportunity to seize lands in North Wales. In 1081 Gruffudd ap Cynan, who had just won the throne of Gwynedd from Trahaearn ap Caradog at the Battle of Mynydd Carn was enticed to a meeting with the Earl of Chester and Earl of Shrewsbury and promptly seized and imprisoned, leading to the seizure of much of Gwynedd by the Normans.[49] In the south William the Conqueror advanced into Dyfed founding castles and mints at St David's and Cardiff.[50] Rhys ap Tewdwr of Deheubarth was killed in 1093 in Brycheiniog, and his kingdom was seized and divided between various Norman lordships.[51] The Norman conquest of Wales appeared virtually complete.

In 1094, however, there was a general Welsh revolt against Norman rule, and gradually territories were won back. Gruffudd ap Cynan was eventually able to build a strong kingdom in Gwynedd. His son, Owain Gwynedd, allied with Gruffydd ap Rhys of Deheubarth won a crushing victory over the Normans at the Battle of Crug Mawr in 1136 and annexed Ceredigion. Owain followed his father on the throne of Gwynedd the following year and ruled until his death in 1170.[52] He was able to profit from disunity in England, where King Stephen and the Empress Matilda were engaged in a struggle for the throne, to extend the borders of Gwynedd further east than ever before.

Powys also had a strong ruler at this time in Madog ap Maredudd, but when his death in 1160 was quickly followed by the death of his heir, Llywelyn ap Madog, Powys was split into two parts and never subsequently reunited.[53] In the south, Gruffydd ap Rhys was killed in 1137, but his four sons, who all ruled Deheubarth in turn, were eventually able to win back most of their grandfather's kingdom from the Normans. The youngest of the four, Rhys ap Gruffydd (The Lord Rhys) ruled from 1155 to 1197. In 1171 Rhys met King Henry II and came to an agreement with him whereby Rhys had to pay a tribute but was confirmed in all his conquests and was later named Justiciar of South Wales. Rhys held a festival of poetry and song at his court at Cardigan over Christmas 1176 which is generally regarded as the first recorded Eisteddfod. Owain Gwynedd's death led to the splitting of Gwynedd between his sons, while Rhys made Deheubarth dominant in Wales for a time.[54]

Out of the power struggle in Gwynedd eventually arose one of the greatest of Welsh leaders, Llywelyn ab Iorwerth, also known as Llywelyn Fawr (the Great), who was sole ruler of Gwynedd by 1200[55] and by his death in 1240 was effectively ruler of much of Wales.[56] Llywelyn made his 'capital' and headquarters at Abergwyngregyn on the north coast, overlooking the Menai Strait. His son Dafydd ap Llywelyn followed him as ruler of Gwynedd, but king Henry III of England would not allow him to inherit his father's position elsewhere in Wales.[57] War broke out in 1241 and then again in 1245, and the issue was still in the balance when Dafydd died suddenly at Abergwyngregyn, without leaving an heir in early 1246. Llywelyn the Great's other son, Gruffudd had been killed trying to escape from the Tower of London in 1244. Gruffudd had left four sons, and a period of internal conflict between three of these ended in the rise to power of Llywelyn ap Gruffudd (also known as Llywelyn Ein Llyw Olaf; Llywelyn, Our Last Leader). The Treaty of Montgomery in 1267 confirmed Llywelyn in control, directly or indirectly, over a large part of Wales. However, Llywelyn's claims in Wales conflicted with Edward I of England, and war followed in 1277. Llywelyn was obliged to seek terms, and the Treaty of Aberconwy greatly restricted his authority. War broke out again when Llywelyn's brother Dafydd ap Gruffudd attacked Hawarden Castle on Palm Sunday 1282. On 11 December 1282, Llywelyn was lured into a meeting in Builth Wells castle with unknown Marchers, where he was killed and his army subsequently destroyed. His brother Dafydd ap Gruffudd continued an increasingly forlorn resistance. He was captured in June 1283 and was hanged, drawn and quartered at Shrewsbury. In effect Wales became England's first colony until it was finally annexed through the Laws in Wales Acts 1535-1542.

Conquest: from the Statute of Rhuddlan to the Laws in Wales Acts 1283–1542

After the passing the Statute of Rhuddlan (1284), which restricted Welsh laws, King Edward I's ring of impressive stone castles assisted in the domination of Wales, and he crowned his conquest by giving the title Prince of Wales to his son and heir in 1301.[58] Wales became, effectively, part of England, even though its people spoke a different language and had a different culture. English kings appointed a Council of Wales, sometimes presided over by the heir to the throne. This Council normally sat in Ludlow, now in England but at that time still part of the disputed border area in the Welsh Marches. Welsh literature, particularly poetry, continued to flourish, however, with the lesser nobility now taking over from the princes as the patrons of the poets. Many consider Dafydd ap Gwilym, who flourished in the middle of the 14th century, the greatest of the Welsh poets.

There were a number of rebellions including ones led by Madog ap Llywelyn in 1294–1295[59] and by Llywelyn Bren, Lord of Senghenydd, in 1316–1318. In the 1370s the last representative in the male line of the ruling house of Gwynedd, Owain Lawgoch, twice planned an invasion of Wales with French support. The English government responded to the threat by sending an agent to assassinate Owain in Poitou in 1378.[60]

In 1400, a Welsh nobleman, Owain Glyndŵr (or Owen Glendower), revolted against King Henry IV of England. Owain inflicted a number of defeats on the English forces and for a few years controlled most of Wales. Some of his achievements included holding the first Welsh Parliament at Machynlleth and plans for two universities. Eventually the king's forces were able to regain control of Wales and the rebellion died out, but Owain himself was never captured. His rebellion caused a great upsurge in Welsh identity and he was widely supported by Welsh people throughout the country.[61]

As a response to Glyndŵr's rebellion, the English parliament passed the Penal Laws against Wales. These prohibited the Welsh from carrying arms, from holding office and from dwelling in fortified towns. These prohibitions also applied to Englishmen who married Welsh women. These laws remained in force after the rebellion, although in practice they were gradually relaxed.[62]

In the Wars of the Roses which began in 1455 both sides made considerable use of Welsh troops. The main figures in Wales were the two Earls of Pembroke, the Yorkist Earl William Herbert and the Lancastrian Jasper Tudor. In 1485 Jasper's nephew, Henry Tudor, landed in Wales with a small force to launch his bid for the throne of England. Henry was of Welsh descent, counting princes such as Rhys ap Gruffydd (The Lord Rhys) among his ancestors, and his cause gained much support in Wales. Henry defeated King Richard III of England at the Battle of Bosworth with an army containing many Welsh soldiers and gained the throne as King Henry VII of England.[63]

Under his son, Henry VIII of England, the Laws in Wales Acts 1535-1542 were passed, integrating Wales with England in legal terms, abolishing the Welsh legal system, and banning the Welsh language from any official role or status, but it did for the first time define the England-Wales border and allowed members representing constituencies in Wales to be elected to the English Parliament.[64] They also abolished any legal distinction between the Welsh and the English, thereby effectively ending the Penal Code although this was not formally repealed.[65]

Early modern period

Following Henry VIII's break with Rome and the Pope, Wales for the most part followed England in accepting Anglicanism, although a number of Catholics were active in attempting to counteract this and produced some of the earliest books printed in Welsh. In 1588 William Morgan produced the first complete translation of the Welsh Bible.[4][66] Morgan's Bible is one of the most significant books in the Welsh language, and its publication greatly increased the stature and scope of the Welsh language and literature.[4]

Wales was overwhelmingly Royalist in the Wars of the Three Kingdoms in the early 17th century though there were some notable exceptions such as John Jones Maesygarnedd and the Puritan writer Morgan Llwyd.[67] Wales was an important source of men for the armies of King Charles I of England,[68] though no major battles took place in Wales. The Second English Civil War began when unpaid Parliamentarian troops in Pembrokeshire changed sides in early 1648.[69] Colonel Thomas Horton defeated the Royalist rebels at the battle of St. Fagans in May and the rebel leaders surrendered to Cromwell on 11 July after the protracted two-month siege of Pembroke.

Education in Wales was at a very low ebb in this period, with the only education available being in English while the majority of the population spoke only Welsh. In 1731 Griffith Jones started circulating schools in Carmarthenshire, held in one location for about three months before moving (or "circulating") to another location. The language of instruction in these schools was Welsh. By Griffith Jones' death, in 1761, it is estimated that up to 250,000 people had learnt to read in schools throughout Wales.[70]

The 18th century also saw the Welsh Methodist revival, led by Daniel Rowland, Howell Harris and William Williams Pantycelyn.[71] In the early 19th century the Welsh Methodists broke away from the Anglican church and established their own denomination, now the Presbyterian Church of Wales. This also led to the strengthening of other nonconformist denominations, and by the middle of the 19th century Wales was largely Nonconformist in religion. This had considerable implications for the Welsh language as it was the main language of the nonconformist churches in Wales. The Sunday schools which became an important feature of Welsh life made a large part of the population literate in Welsh, which was important for the survival of the language as it was not taught in the schools.

The end of the 18th century saw the beginnings of the Industrial Revolution, and the presence of iron ore, limestone and large coal deposits in south-east Wales meant that this area soon saw the establishment of ironworks and coal mines, notably the Cyfarthfa Ironworks and the Dowlais Ironworks at Merthyr Tydfil.

Modern history

Population

| Year | Population[72] |

| 1536 | 278,000 |

| 1620 | 360,000 |

| 1770 | 500,000 |

| 1801 | 587,000 |

| 1851 | 1,163,000 |

| 1911 | 2,421,000 |

| 1921 | 2,656,000 |

| 1939 | 2,487,000 |

| 1961 | 2,644,000 |

| 1991 | 2,812,000 |

| 2011 | 3,064,000 |

The population of Wales doubled from 587,000 in 1801 to 1,163,000 in 1851 and had reached 2,421,000 by 1911. Most of the increase came in the coal mining districts especially Glamorganshire, which grew from 71,000 in 1801 to 232,000 in 1851 and 1,122,000 in 1911.[73] Part of this increase can be attributed to the demographic transition seen in most industrialising countries during the Industrial Revolution, as death-rates dropped and birth-rates remained steady. However, there was also a large-scale migration of people into Wales during the industrial revolution. The English were the most numerous group, but there were also considerable numbers of Irish and smaller numbers of other ethnic groups,[74][75] including Italians, migrated to South Wales.[76] Wales received other immigration from various parts of the British Commonwealth of Nations in the 20th century, and African-Caribbean and Asian communities add to the ethno-cultural mix, particularly in urban Wales.[77]

1900–1914

The modern history of Wales starts in the 19th century when South Wales became heavily industrialised with ironworks; this, along with the spread of coal mining to the Cynon and Rhondda valleys from the 1840s, led to an increase in population.[78] The social effects of industrialisation resulted in armed uprisings against the mainly English owners.[79] Socialism developed in South Wales in the latter part of the century, accompanied by the increasing politicisation of religious Nonconformism. The first Labour MP, Keir Hardie, was elected as junior member for the Welsh constituency of Merthyr Tydfil and Aberdare in 1900.[80]

The first decade of the 20th century was the period of the coal boom in South Wales, when population growth exceeded 20 per cent.[81] Demographic changes affected the language frontier; the proportion of Welsh speakers in the Rhondda valley fell from 64 per cent in 1901 to 55 per cent ten years later, and similar trends were evident elsewhere in South Wales.[82]

Kenneth O. Morgan argues that the 1850–1914 era:

- was a story of growing political democracy with the hegemony of the Liberals in national and local government, of an increasingly thriving economy in the valleys of south Wales, the world’s dominant coal-exporting area with massive ports at Cardiff and Barry, an increasingly buoyant literature and a revival in the eisteddfod, and of much vitality in the nonconformist chapels especially after the short-lived impetus from the ‘great revival’, Y Diwygiad Mawr, of 1904–5. Overall, there was a pervasive sense of strong national identity, with a national museum, a national library and a national university as its vanguard.[83]

1914–1945

The world wars and interwar period were hard times for Wales, in terms of the faltering economy of antiwar losses, and a deep sense of insecurity. Men eagerly volunteered for war service.[84] Morgan argues:

- 1914–45, there was an abrupt and corrosive change. First World War was an ordeal not only for the loss of life, but for the startling collapse of economic life in south Wales and much resultant social deprivation. The war also saw the downfall of Lloyd George’s Liberal Party and the concordant national revival of pre-1914. The Welsh-speaking world went into retreat, though there was powerful compensation in the proliferating Anglo-Welsh poetry and prose of Dylan Thomas and many others. The Second World War brought more upheaval, though also the birth of a revival of the south Wales economy through the stimulus provided by the Board of Trade.[85]

The Labour Party replaced the Liberals as the dominant party in Wales after the First World War, particularly in the industrial valleys of South Wales. Plaid Cymru was formed in 1925 but initially its growth was slow and it gained few votes at parliamentary elections.[86]

Since 1945

Morgan characterizes the recent period as:

- one of broad renewal, political resurgence under the Labour Party and unions, a marked revival of economic growth, with much great material affluence and social welfare. The final period saw a phenomenon little in evidence before 1939, a strong movement towards political nationalism, some success for Plaid Cymru and, after the Kilbrandon Commission, a major attempt to pass Welsh devolution.[85]

The coal industry steadily declined after 1945.[87] By the early 1990s there was only one deep pit still working in Wales. There was a similar catastrophic decline in the steel industry (the steel crisis), and the Welsh economy, like that of other developed societies, became increasingly based on the expanding service sector.

In May 1997, a Labour government was elected with a promise of creating devolved institutions in Scotland and Wales. In late 1997 a referendum was held on the issue which resulted a "yes" vote. The Welsh Assembly was set up in 1999 (as a consequence of the Government of Wales Act 1998) and possesses the power to determine how the government budget for Wales is spent and administered.

The results of the 2001 Census showed an increase in the number of Welsh speakers to 21% of the population aged 3 and older, compared with 18.7% in 1991 and 19.0% in 1981. This compares with a pattern of steady decline indicated by census results during the 20th century.[88] The 2011 census showed that decline to have resumed. Though still higher than in 1991, the number of people aged 3 and over able to speak Welsh in Wales decreased from 582,000 (20.8 per cent) in 2001, to 562,000 (19.0 per cent) in 2011.[89]

The Government of Wales Act 2006 (c 32) is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom that reformed the National Assembly for Wales and allows further powers to be granted to it more easily. The Act creates a system of government with a separate executive drawn from and accountable to the legislature. Following a successful referendum in 2011 on extending the law making powers of the National Assembly it is now able to make laws, known as Acts of the Assembly, on all matters in devolved subject areas, without needing the UK Parliament's agreement. In the 2016 referendum, Wales joined England in endorsing Brexit and rejecting membership of the European Union.

In May 2020, the National Assembly for Wales was renamed "Senedd Cymru" or "the Welsh Parliament", commonly known as the "Senedd" in both English and Welsh.

Religion

Reformation

Bishop Richard Davies and dissident Protestant cleric John Penry introduced Calvinist theology to Wales. They used the model of the Synod of Dort of 1618–1619. Calvinism developed through the Puritan period, following the restoration of the monarchy under Charles II, and within Wales' Methodist movement. However few copies of Calvin's works were available before the mid-19th century.[90] In 1567 Davies, William Salesbury, and Thomas Huet completed the first modern translation of the New Testament and the first translation of the Book of Common Prayer (Welsh: Y Llyfr Gweddi Gyffredin). In 1588 William Morgan completed a translation of the whole Bible. These translations were as important to the survival of the Welsh language and had the effect of conferring status on Welsh as a liturgical language and vehicle for worship. This had a significant role in its continued use as a means of everyday communication and as a literary language down to the present day despite the pressure of English.

Nonconformity

Nonconformity was a significant influence in Wales from the eighteenth to the twentieth centuries. The Welsh Methodist revival of the 18th century was one of the most significant religious and social movements in the history of Wales. The revival began within the Church of England in Wales and at the beginning remained as a group within it, but the Welsh revival differed from the Methodist revival in England in that its theology was Calvinist rather than Arminian. Welsh Methodists gradually built up their own networks, structures, and even meeting houses (or chapels), which led eventually to the secession of 1811 and the formal establishment of the Calvinistic Methodist Presbyterian church of Wales in 1823.[91]

The Welsh Methodist revival also had an influence on the older nonconformist churches, or dissenters the Baptists and the Congregationalists who in turn also experienced growth and renewal. As a result, by the middle of the nineteenth century, Wales was predominantly a nonconformist country.

The 1904–1905 Welsh Revival was the largest full scale Christian revival of Wales of the 20th century. It is believed that at least 100,000 people became Christians during the 1904–1905 revival, but despite this it did not put a stop to the gradual decline of Christianity in Wales, only holding it back slightly.[92]

Historiography

Until recently, says Martin Johnes:

- the historiography of modern Wales was rather narrow. Its domain was the fortunes of the Liberals and Labour, the impact of trade unions and protest, and the cultural realms of nonconformity and the Welsh language. This was not surprising—all emergent fields start with the big topics and the big questions—but it did give much of Welsh academic history a rather particular flavour. It was institutional and male, and yet still concerned with fields of enquiry that lay outside the confines of the British establishment.[93]

See also

- History of the United Kingdom

- Archaeology of Wales

- History of women in the United Kingdom

- Economic history of the United Kingdom

- List of Anglo-Welsh Wars

- The Red Dragon

- The Cambrian Quarterly Magazine and Celtic Repertory

- British military history

Notes

- Davies, J A History of Wales, pp. 3–4.

- Richards, MP; Trinkaus, E (September 2009). "Out of Africa: modern human origins special feature: isotopic evidence for the diets of European Neanderthals and early modern humans". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106 (38): 16034–9. doi:10.1073/pnas.0903821106. PMC 2752538. PMID 19706482.

- Koch, pp. 291–292.

- Davies, John (Ed) (2008). The Welsh Academy Encyclopaedia of Wales. Cardiff: University of Wales Press. p. 572. ISBN 978-0-7083-1953-6.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Williams G.A.When was Wales? p. 174

- "Gathering the Jewels". Early Neanderthal jaw fragment, c. 230,000 years old. Culturenet Cymru. 2008. Archived from the original on 29 February 2012. Retrieved 25 September 2008.

- Davies, J A History of Wales, p. 3.

- Lynch, F. Prehistoric Anglesey pp.34–42, 58

- "Tinkinswood". www.valeofglamorgan.gov.uk. Accessed 3 August 2008

- Lynch, F. Gwynedd pp. 39–40

- Davies, J The Making of Wales p. 23

- Davies, J A history of Wales p. 19

- Lynch, F. Prehistoric Anglesey pp.249–77

- Special report: 'Myths of British ancestry' by Stephen Oppenheimer | Prospect Magazine October 2006 issue 127

- Capelli; et al. (2003). "A Y Chromosome Census of the British Isles". Current Biology. 13 (11): 979–984. doi:10.1016/s0960-9822(03)00373-7. PMID 12781138.

- Jones 1990:151, An Atlas of Roman Britain, The Development of the Provinces.

- Jones 1990:154, An Atlas of Roman Britain, The Development of the Provinces.

- Giles 1841:27, The Works of Gildas, De Excidio, ch. 31: Gildas, writing c. 540, condemns the "tyrant of the Demetians".

- Jones 1990:179–196, An Atlas of Roman Britain, The Economy

- Frere 1987:354, Britannia, The End of Roman Britain.

- Giles 1841:13, The Works of Gildas, The History, ch. 14. Gildas, writing c. 540, says that Maximus left Britain not only with all of its Roman troops, but also with all of its armed bands, governors, and the flower of its youth, never to return.

- Phillimore, Egerton, ed. (1887), "Pedigrees from Jesus College MS. 20", Y Cymmrodor, VIII, Honourable Society of Cymmrodorion, pp. 83–92

- Phillimore, Egerton (1888), "The Annales Cambriae and Old Welsh Genealogies, from Harleian MS. 3859", in Phillimore, Egerton (ed.), Y Cymmrodor, IX, Honourable Society of Cymmrodorion, pp. 141–183

- Rachel Bromwich, editor and translator. Trioedd Ynys Prydein: The Welsh Triads. Cardiff: University of Wales Press, Third Edition, 2006. 441–444

- Laing 1990:108, Celtic Britain and Ireland, c. 200–800, The non-Romanized zone of Britannia.

- Laing 1975:93, Early Celtic Britain and Ireland, Wales and the Isle of Man.

- Miller, Mollie (1977), "Date-Guessing and Dyfed", Studia Celtica, 12, Cardiff: University of Wales, pp. 33–61

- Coplestone-Crow, Bruce (1981), "The Dual Nature of Irish Colonization of Dyfed in the Dark Ages", Studia Celtica, 16, Cardiff: University of Wales, pp. 1–24

- Meyer, Kuno (1896), "Early Relations Between Gael and Brython", in Evans, E. Vincent (ed.), Transactions of the Honourable Society of Cymmrodorion, Session 1895–1896, I, London: Honourable Society of Cymmrodorion, pp. 55–86

- "A History of Wales", by Sir John Edward LLoyd

- Lynch, F. Gwynedd p. 126.

- Davies, J. A History of Wales p. 52.

- Lloyd, J.E. A History of Wales pp. 143–159

- Chromosome survey

- Rickard, J (9 September 2000), Battle of Chester, c.613–616

- Lloyd, J.E. A History of Wales p. 131.

- Maund, Kari The Welsh kings p. 36.

- There is a divergence between interpretations of Bede's dates which has led to confusion about whether Cadwallon was killed in 634 or the year earlier, 633. Cadwallon died in the year after the Battle of Hatfield Chase, which Bede reports as occurring in October 633; but if Bede's years started in September, as several historians have argued, then Hatfield Chase would have occurred in 632, and therefore Cadwallon would have died in 633. Other historians have argued against this view of Bede's chronology, however, favouring the dates as he gives them.

- Davies, J. A history of Wales p. 64.

- Davies, J. A history of Wales pp. 65–6.

- For a discussion of this see Stephenson Governance of Gwynedd pp. 138–141

- Maund, Kari The Welsh kings p. 50–54

- Lloyd, J.E. A History of Wales p. 337.

- Lloyd, J.E. A History of Wales pp. 343–4.

- Lloyd, J.E. A History of Wales pp. 351–2.

- K. L. Maund (1991). Ireland, Wales, and England in the Eleventh Century. Boydell & Brewer Ltd. pp. 216–. ISBN 978-0-85115-533-3.

- Maund, Kari The Welsh kings p.87-97

- Davies, R.R. Conquest, coexistence and change pp. 28–30.

- Maund, Kari The Welsh kings p. 110.

- Political Chronology of Wales, 4–5.

- Lloyd, J.E. A History of Wales p. 398.

- Maund, Kari The Welsh kings pp. 162–171.

- Lloyd, J.E. A History of Wales pp. 508–9.

- Lloyd, J.E. A History of Wales p. 536

- Moore, D. The Welsh wars of independence p.108-9

- Moore, D. The Welsh wars of independence p.124

- Lloyd, J.E. A History of Wales p.693

- Davies, R.R. Conquest, coexistence and change p. 386.

- Moore, D. The Welsh wars of independence p. 159.

- Moore, D. The Welsh wars of independence p.164-6

- Moore, D. The Welsh Wars of Independence pp. 169–85.

- Davies, J. A History of Wales p. 199.

- Williams, G. Recovery, reorientation and reformation pp. 217–26

- Williams, G. Recovery, reorientation and reformation pp. 268–73

- Davies, J. A History of Wales p.233

- Williams, G. Recovery, reorientation and reformation pp. 322–3

- Jenkins, G. H. The foundations of modern Wales p. 7

- Jenkins, G. H. The foundations of modern Wales p. 5-6

- Davies, J. A History of Wales p. 280

- Jenkins, G. H. The foundations of modern Wales pp. 370–377

- Jenkins, G.H. The foundations of modern Wales pp. 347–50

- John Davies (1993). A History of Wales. pp. 258–59, 319. ISBN 9780141926339.; Census 2001, 200 Years of the Census in ... Wales (2001)

- Brian R. Mitchell and Phyllis Deane, Abstract of British Historical Statistics (Cambridge, 1962) pp 20, 22

- "Industrial Revolution". BBC. Retrieved 17 October 2009.

- LSJ Services [Wales] Ltd. "Population therhondda.co.uk. Retrieved 9 May 2006". Therhondda.co.uk. Archived from the original on 20 May 2008. Retrieved 17 October 2009.

- "BBC Wales — History — Themes — Italian immigration". BBC. Retrieved 17 October 2009.

- Interview with Mohammed Asghar AM

- Williams G.A.When was Wales? p. 183

- Davies, J A history of Wales p. 366-7

- Morgan, K.O. Rebirth of a nation pp. 46–7

- Jenkins, P. (1992) A History of Modern Wales. Harlow: Longman.

- Evans, D. Gareth (1989) A History of Wales 1815–1906. Cardiff: University of Wales Press.

- Kenneth O. Kenneth, Kenneth O. Morgan: My Histories (University of Wales Press, 2015) p 95.

- Gervase Phillips, "Dai bach y soldiwr: Welsh soldiers in the British Army, 1914–1918." Llafur 6 (1993): 94-105.

- Morgan, My Histories (2015) p 95.

- Morgan, K.O. Rebirth of a nation p.206-8, 272

- Davies, A history of Wales p. 533

- Results of the 2001 Census from www.statistics.gov.uk

- http://wales.gov.uk/topics/statistics/headlines/population2012/121211/?lang=en

- D. Densil Morgan, "Calvinism in Wales: c.1590–1909," Welsh Journal of Religious History (2009), Vol. 4, p22-36

- Peter Yalden, "Association, Community and the Origins of Secularisation: English and Welsh Nonconformity, c. 1850–1930." Journal of Ecclesiastical History 55#2 (2004): 293-324.

- Edward J. Gitre, "The 1904–05 Welsh Revival: Modernization, Technologies, and Techniques of the Self." Church history 73#4 (2004): 792-827.

- Martin Johnes, Review, 20 Century British History (2016) 27#3 p 492

Further reading and references

- Beddoe, Deirdre. Out of the shadows: A history of women in twentieth-century Wales (University of Wales Press, 2000).

- Cunliffe, Barry (1987) Iron Age communities in Britain' (Routledge & Kegan Paul, 2nd ed) ISBN 0-7100-8725-X

- Davies, John. (1994) A History of Wales (Penguin Books) ISBN 0-14-014581-8

- Davies, John. (2009) The Making of Wales (The History Press) 2nd edition ISBN 978-0-7524-5241-8

- Davies, R.R. (1987) Conquest, coexistence and change: Wales 1063–1415 (Clarendon Press, University of Wales Press) ISBN 0-19-821732-3 Online from Oxford University Press: DOI:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198208785.001.0001

- Davies, Russell. People, Places and Passions:" Pain and Pleasure": A Social History of Wales and the Welsh, 1870–1945 (University of Wales Press, 2015).

- Frere, Sheppard Sunderland (1987), Britannia: A History of Roman Britain (3rd, revised ed.), London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, ISBN 0-7102-1215-1

- Giles, John Allen, ed. (1841), "The Works of Gildas", The Works of Gildas and Nennius, London: James Bohn

- Jenkins, Geraint H. (1987) The foundations of modern Wales, 1642–1780 (Clarendon Press, University of Wales Press) ISBN 0-19-821734-X

- Jones, Barri; Mattingly, David (1990), An Atlas of Roman Britain, Cambridge: Blackwell Publishers (published 2007), ISBN 978-1-84217-067-0

- Johnes, Martin. "For Class and Nation: Dominant Trends in the Historiography of Twentieth‐Century Wales." History Compass 8#11 (2010): 1257–1274.

- Koch, John T. (2006). Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO.

- Laing, Lloyd (1975), "Wales and the Isle of Man", The Archaeology of Late Celtic Britain and Ireland, c. 400–1200 AD, Frome: Book Club Associates (published 1977), pp. 89–119

- Laing, Lloyd; Laing, Jennifer (1990), "The non-Romanized zone of Britannia", Celtic Britain and Ireland, c. 200–800, New York: St. Martin's Press, pp. 96–123, ISBN 0-312-04767-3

- John Edward Lloyd (1911) A history of Wales: from the earliest times to the Edwardian conquest (Longmans, Green & Co.)

- Frances Lynch (1995) Gwynedd (A guide to ancient and historic Wales series) (HMSO) ISBN 0-11-701574-1

- Frances Lynch (1970) Prehistoric Anglesey: the archaeology of the island to the Roman conquest (Anglesey Antiquarian Society)

- Maund, Kari. (2006) The Welsh kings: warriors, warlords and princes (Tempus) ISBN 0-7524-2973-6

- Moore, David. (2005) The Welsh wars of independence: c.410-c.1415 (Tempus) ISBN 0-7524-3321-0

- Morgan, Kenneth O. (1981) Rebirth of a nation: Wales 1880–1980 (Oxford University Press, University of Wales Press) ISBN 0-19-821736-6

- Remfry, P.M. (2003) A Political Chronology of Wales, 1066 to 1282 (ISBN 1-899376-75-5)

- Ross, David. Wales History of a Nation (2nd ed. 2014)

- Stephenson, David. (1984) The governance of Gwynedd (University of Wales Press) ISBN 0-7083-0850-3

- Williams, Glanmor (1987) Recovery, reorientation and reformation: Wales c.1415–1642 (Clarendon Press, University of Wales Press) ISBN 0-19-821733-1

- Williams, Gwyn A. (1985) When was Wales?: a history of the Welsh (Black Raven Press) ISBN 0-85159-003-9

- Withey, Alun. "Unhealthy Neglect? The Medicine and Medical Historiography of Early Modern Wales." Social history of medicine 21.1 (2008): 163–174. online

- Withey, Alun. "Health, Medicine and the Family in Wales, c. 1600-1750." (2009). online

Religion

- Chambers, Paul, and Andrew Thompson. "Coming to terms with the past: religion and identity in Wales." Social compass 52.3 (2005): 337–352.

- Davies, Ebnezer Thomas. Religion in the Industrial Revolution of South Wales (U. of Wales Press, 1965)

- Jenkins, Geraint H. Literature, religion and society in Wales, 1660-1730 (University of Wales Press, 1978)

- Horace Mann (1854). Census of Great Britain, 1851: Religious Worship in England and Wales. Ge. Routledge.

- Morgan, Derec Llwyd. The Great Awakening in Wales (Epworth Press, 1988)

- Walker, R. B. "The Growth of Wesleyan Methodism in Victorian England and Wales." The Journal of Ecclesiastical History 24.03 (1973): 267–284.

- Williams, Glanmor. The Welsh Church from Conquest to Reformation (University of Wales Press, 1976)

- Williams, Glanmor. The Welsh Church from Reformation to Disestablishment: 1603–1920 (University of Wales Press, 2007)

- Williams, Glanmor, ed. Welsh reformation essays (University of Wales Press, 1967)

- Yalden, Peter. "Association, Community and the Origins of Secularisation: English and Welsh Nonconformity, c. 1850–1930." The Journal of Ecclesiastical History 55.02 (2004): 293–324.

Primary sources

- Brut y Tywysogyon or The Chronicle of the Princes. Peniarth Ms. 20 version, ed. and trans. T. Jones [Cardiff, 1952]

- Annales Cambriae. A Translation of Harleian 3859; PRO E.164/1; Cottonian Domitian, A 1; Exeter Cathedral Library MS. 3514 and MS Exchequer DB Neath, PRO E (ISBN 1-899376-81-X)

External links

- Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales

- National Library of Wales official website - includes historical information and resources

- BBC History – Wales

- History and Ancestry webpage from the Welsh Government