Politics in the British Isles

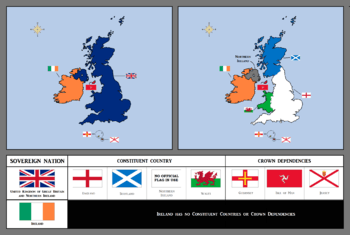

The British Isles comprise two sovereign states, Republic of Ireland and the United Kingdom, and three dependencies of the British Crown,[1][2] Guernsey, Jersey and the Isle of Man.

Ireland is a unitary state and a republic. Since 1998, it shares certain common institutions with Northern Ireland, in the United Kingdom, from which it was partitioned in 1921. The United Kingdom is a constitutional monarchy and also a unitary state[3] comprising England, Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland. Also since 1998, the United Kingdom has devolved significant domestic powers (though differing in extent) to administrations in Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales. Jersey, the Isle of Man, and Guernsey (including its two semi-autonomous territories of Alderney and Sark), are collectively known as the Crown Dependencies; although not part of the United Kingdom, the UK is responsible for their defence and international relations on behalf of the British Crown.[4][5]

In 1998, as part of the Good Friday Agreement, Ireland and the United Kingdom established a number of organisations, including the British-Irish Intergovernmental Conference and the British-Irish Council, the latter being a multilateral body in which both sovereign states, the three devolved administrations of the UK and the three Crown dependencies participate. Additionally, there are numerous relations between the countries in the British Isles, including formal and informal bilateral and multilateral relations between Ireland, the devolved administrations of the UK, and the crown dependencies, as well as shared cultural and economic links.

History

Governments

The British Isles contain two sovereign states:

- Ireland, also known as the Republic of Ireland

- the United Kingdom, within which certain powers are devolved:

- to the Scottish Government, Welsh Government, and the Northern Ireland Executive

The archipelago also contains three Crown dependencies:

- Jersey, Isle of Man, and Guernsey, which contains the somewhat autonomous Alderney and Sark.

The Crown dependencies are constitutionally linked to the United Kingdom but independent of it.

Ireland

Ireland is a parliamentary republic[6] comprising approximately five sixths of the island of Ireland in the west of the archipelago.

The island of Ireland was partitioned in 1920 with the Government of Ireland Act into the 26 counties of Southern Ireland and the six counties of Northern Ireland. In 1921 Southern Ireland was renamed the Irish Free State when it gained independence from the United Kingdom following the Irish War of Independence. Since the passage in 1949 of the Republic of Ireland Act, the Republic of Ireland is no longer part of the commonwealth.

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom is a constitutional monarchy that covers the whole of the island of Great Britain in the east of the archipelago, a north-eastern part of the island of Ireland, and many smaller surrounding islands including Orkney and Shetland.

The United Kingdom comprises four parts: the countries of England, Scotland and Wales and the province of Northern Ireland.[7] All but Northern Ireland have been independent states at one point and each have their own history and sense of identity.

Devolution

Northern Ireland has had a degree of self-government for most of the time since 1921. In 1998, following referendums in Scotland, Wales, and both parts of Ireland, a range of powers were transferred to Scotland and Wales as well as restoring self-government in Northern Ireland Executive. England does not have self-government.

Crown dependencies

The Crown dependencies of Guernsey and Jersey, in the south of the archipelago (and geographically closer to France), and the Isle of Man, in the Irish Sea between Great Britain and Ireland, are self-governing states but independent. The Bailiwick of Guernsey furthermore contains two smaller islands, which also have a certain degree of autonomy: Sark and Alderney.

The Crown dependencies are not part of the United Kingdom. They are administered independently by their own governments, legislatures and judiciaries, but are not sovereign. The United Kingdom, on behalf of the British Crown, is responsible for their international relations and defence, and the Crown is ultimately responsible for their good governance.[8] They can be legislated for from the Parliament of the United Kingdom, although in practice the UK rarely exercises this power.[9]

While the Crown dependencies are not part of the United Kingdom, residents of the Isle of Man, Jersey and Guernsey are nonetheless considered British citizens, and European Union citizens by extension (with some exceptions), and are given British passports (albeit with a special cover for each Crown dependency). Nevertheless, British citizens from outside of each Crown dependency and Irish citizens may require work permits in order to work on the islands[10] although usually this is merely a formality. There have been discussions within some of the Crown dependencies about greater independence from the Crown, but they have not yet gained strong popular or governmental support.[11]

Relations

Intergovernmental bodies

The following is a summary of the intergovernmental bodies and collaboration platforms in the British Isles (note: this list does not include bodies that exist solely in the United Kingdom such as the Joint Ministerial Committee)

| Organization/Platform | Purpose | Members |

|---|---|---|

| British-Irish Council | multilateral cooperation on areas of joint interest | Ireland, United Kingdom, Scotland, Isle of Man, Jersey, Guernsey, Wales, Northern Ireland |

| British-Irish Parliamentary Assembly | Foster understanding between parliamentarians | Ireland, United Kingdom, Scotland, Isle of Man, Jersey, Guernsey, Wales, Northern Ireland |

| North-South Ministerial Council | All-island cooperation for Ireland | Ireland, Northern Ireland |

| British–Irish Intergovernmental Conference | bilateral cooperation | Ireland, United Kingdom |

| Irish Sea Region | Joint planning for use of the Irish sea | Ireland, Northern Ireland, Scotland, Isle of Man, various regional/local governments, NGOs, and universities |

| Ireland Wales Programme | body that implements EU regional development projects | Ireland, Wales |

| Cities of the Isles | Collaboration platform amongst several large cities in Ireland and the UK | Dublin, Liverpool, Belfast, Glasgow, Edinburgh, Cardiff[12] |

| Columba Project | Partnership to promote use of Gaelic | Ireland, Northern Ireland, Scotland (Isle of Man also participates to some extent) |

| Various municipal/local government linkages | Commerce, cultural exchange, tourism, environmental development, etc. | Several municipal/local government collaborations between Ireland/Scotland/Northern Ireland are outlined in An Inquiry into the Possibility of a Programme of Co-operation between Scotland and Ireland |

Multilateral relations

The main body for multilateral international relations in the islands, since 1998, is the British–Irish Council. The British-Irish Council (BIC) is an international organisation[13] established under the Belfast Agreement in 1998. Its membership comprises representatives from:

- The two sovereign governments of Ireland and the United Kingdom

- The three devolved administrations of Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales

- The crown dependencies of Guernsey, the Isle of Man and Jersey.

The Council formally came into being on 2 December 1999. Its stated aim is to "promote the harmonious and mutually beneficial development of the totality of relationships among the peoples of these islands". The BIC has a standing secretariat, located in Edinburgh, Scotland, and meets in bi-annual summit session and regular ministerial meetings.[14] It has been suggested that the BIC provides a more equitable forum for participation of the devolved administrations than the UK-only Joint Ministerial Council, and that it has created a "novel political and administrative space for intergovernmental co-operation."[15]

Some researchers have compared the British-Irish council to similar multilateral bodies amongst the Nordic countries: the Nordic Council and the Nordic Council of Ministers.[16]

- British-Irish Parliamentary Assembly

In addition to the council, there is also the British–Irish Parliamentary Assembly (BIPA), a deliberative body consisting of members of legislative bodies in the United Kingdom, Ireland, and the British crown dependencies. Its purpose is to foster common understanding between elected representatives from these jurisdictions.

The assembly consists of 25 members of each of the two sovereign parliaments: the Parliament of the United Kingdom and the Oireachtas (the Irish parliament). It also includes as five representatives from the Scottish Parliament, five from the National Assembly for Wales, five from the Northern Ireland Assembly, and one each from the States of Jersey, the States of Guernsey and the Tynwald of the Isle of Man.[17]

- Common travel area

Various arrangements over the years have led to the development of the Common Travel Area, a passport-free zone that comprises the islands of Ireland, Great Britain, the Isle of Man and the Channel Islands. The area's internal borders are subject to minimal or non-existent border controls and can normally be crossed by Irish and British citizens with only minimal identity documents, if any.[18]

- Inter-island relations

The three crown dependencies, while independent, share a relatively similar position with respect to the United Kingdom and with international bodies such as the EU or the OECD. As a result, the crown dependencies work together on areas of mutual interest. For example, in 2000, the three states cooperated on development of common policies for offshore banking.[19] In 2003, they developed a joint approach to certain EU activities around tax information.[20][21] The heads of government of the crown dependencies, including Isle of Man, Guernsey, Alderney, Sark, and Jersey, meet at an annual inter-island summit, to discuss matters of common concern, such as financial regulation and relations with the UK.[22][23][24]

On 24 January 2013 Jersey, Guernsey and the Isle of Man signed double taxation agreements with each other (in the case of Jersey and Guernsey, updating the existing agreement) .[25] This was the first time all three Crown Dependencies had established such mutual agreements which also included provision for exchange of tax information equivalent to TIEAs.[26]

Bilateral relations

Besides the dominant strand of Anglo-Irish relations (also known as the East-West strand or the Dublin-London axis), other bilateral relations exist between the various countries in the archipelago. Indeed, fostering such bilateral and multilateral relations between the countries was an explicit goal of the British Irish council.[27][28]

One important body is the North/South Ministerial Council (NSMC) [29] a body established by the British and Irish governments under the Good Friday Agreement to co-ordinate activity and exercise certain governmental powers across the whole island of Ireland. The Council takes the form of meetings between ministers from both the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland and is responsible for twelve policy areas. Six of these areas are the responsibility of corresponding North/South Implementation Bodies.

The Republic of Ireland has also established bilateral relations with three Crown dependencies: the Isle of Man, Jersey and Guernsey, for example through the signing of various bilateral tax agreements.[30]

The crown dependencies are also pursuing direct linkages with other countries in the Isles. For example, Scotland's first minister was invited to the Isle of Man in 2008, the first such visit of a Scottish minister to the Island.[31] In 2010, the two governments had a dispute over Isle of Man government laws restricting scallop fishing in the Irish sea, which were seen as unfair to Scottish fishermen.[32] Since 2011 the government of Jersey has sent representatives to the main party conferences of the United Kingdom, its "most significant economic partner", as part of a commitment to enhancing political engagement with the UK. In 2012 the Assistant Chief Minister attended the conference of the UK Liberal Democrats, the Chief Minister attended the UK Labour Party conference, and the Deputy Chief Minister and Treasury and Resources Minister were announced to attend the UK Conservative Party conference.[33] The Deputy Chief Minister of Guernsey also attended the UK Liberal Democrats conference in 2012 to communicate the message that "Guernsey and the Channel Islands are good neighbours to the UK".[34] The Chief Minister of Guernsey, accompanied by the Commerce and Employment Minister, has been announced to attend the UK Conservative Party conference 2012.[35] Guernsey's Deputy Chief Minister and Jersey's Assistant Chief Minister travelled to Dublin in September 2012 as a first step in a more coordinated approach to international relations. The purpose of the visit was to meet Ireland's Minister for European Affairs ahead of Ireland's assumption of the European Union presidency in 2013 for mutual discussions.[36]

Ireland has also established bilateral relationships with Wales and Scotland. In 1999, Ireland opened consulates in Edinburgh and Cardiff, although the Cardiff consulate was closed in 2009 in order to cut costs.[37] The Irish and Welsh governments are collaborating on various economic development projects through the auspices of the Ireland Wales Programme, funded by the European Union.[38] Scotland and Ireland are also pursuing various forms of bilateral cooperation, evidenced by visits of the Irish Prime Minister to address the Scottish Parliament, and public statements by Scottish leaders calling for closer bilateral ties between Ireland and Scotland.[39][40]

With the creation of devolved administrations in the UK, there are also increasing bilateral and multilateral relations between the constituent countries of the UK, covered in more detail in Politics in the United Kingdom and Devolution in the United Kingdom.[39]

Joint projects

Several joint projects amongst the various countries in the Isles have been undertaken, often around infrastructure and energy. For example, the governments of Ireland, Scotland, and Northern Ireland are collaborating on the ISLES project, which will facilitate the development of offshore renewable energy sources, such as wind, wave and tidal energy, and renewable energy trade between Scotland, Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland.[41]

Through the auspices of the British-Irish council, Ministers from the UK, Ireland, Isle of Man and the Channel Islands have agreed to work on energy cooperation and development through what is called the All Islands Approach (AIA), facilitating closer links between the energy markets of the various countries.[42]

Isle of Man and Ireland are also planning the development of renewable energy sources, including sharing costs for the development of a wind farm off the coast of the Isle of Man.[43] A wider collaboration is also planned, with Jersey, Guernsey, Isle of Man, and Ireland, to leverage the strong tidal currents around the Channel Islands.[44]

An intergovernmental collaboration platform called the Irish Sea Region has also been set up, managed by the Dublin regional authority. The platform links the governments of Ireland, Isle of Man, the UK, and various local jurisdictions, in order to collaborate on planning for development of the Irish sea and bordering areas.[45]

In 2004, a natural gas interconnection agreement was signed between Ireland and the UK, linking Ireland with Scotland via the Isle of Man.[46]

There are three lighthouse authorities in the British Isles: Northern Lighthouse Board - responsible for Scotland and the Isle of Man; The Trinity House Lighthouse Service - responsible for England, Wales, the Channel Islands and Gibraltar; Commissioners of Irish Lights - responsible for Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland. These three authorities, responsible for provision of navigational aids around the coasts of the British Isles, collaborate closely, and all draw on a single fund administered by the UK Department for Transport and funded through light dues levied on ships calling at UK and Irish ports.[47] Although this broad arrangement will continue, from 2015-16 the work of the Commissioners of Irish Lights in the Republic of Ireland will be funded entirely from domestic sources.[48]

Citizenship and citizens rights

Historically, citizens of Ireland were British subjects. Currently, people born in Northern Ireland are deemed by UK law to be citizens of the United Kingdom (unless neither parent is either a British or Irish citizen). They are also, with similar exceptions, entitled to be citizens of Ireland. This dual entitlement was reaffirmed in the 1998 Good Friday Agreement between the British and Irish governments, which provides that:

"...it is the birthright of all the people of Northern Ireland to identify themselves and be accepted as Irish or British, or both, as they may so choose, and accordingly [the two governments] confirm that their right to hold both British and Irish citizenship is accepted by both Governments and would not be affected by any future change in the status of Northern Ireland."

Ireland and the United Kingdom provide reciprocal recognition to each other's citizens. Irish citizens resident in the UK can vote and stand in any UK elections. United Kingdom citizens resident in Ireland can vote or stand in European and local elections, and vote in parliamentary elections, but cannot vote or stand in Presidential elections or referendums. British and Irish citizens can avail of public services such as health care and social welfare in each other's jurisdiction on an equal basis, and are entitled to the right of abode, with deportation only in the most exceptional of circumstances.

Since the British Nationality Act 1981 came into effect, the Crown dependencies have been treated as part of the United Kingdom for British nationality law purposes.[49] However, each dependency maintains local controls over housing and employment, with special rules applying to British citizens without specified connections to that dependency (as well as to non-British citizens).

Political movements

Unionism

An important political movement in several countries in the Isles is British unionism, an ideology favouring the continued union of the United Kingdom. It is most prevalent in Scotland, England, and Northern Ireland. British unionism has close ties to British nationalism. Another movement is Loyalism, which manifests itself as loyalism to the British Crown.

Nationalism

The converse of unionism, nationalism, is also an important factor for politics in the Isles. Nationalism can take the form of Welsh nationalism, Cornish nationalism, English nationalism, Irish nationalism, Scottish nationalism, Ulster nationalism or independence movements in the Isle of Man or Channel Islands.[50]

Identity

Identity is intertwined with politics, especially in the case of nationalism and independence movements. Details on identity formation in the British Isles can be found at Britishness, Scottish identity, Irish people, Welsh people.

Pan-Celticism is also a movement which is present in several of the countries which have a Celtic heritage.

Political parties

There are no major political parties that are present in all of the countries, but several Irish parties such as Sinn Féin and Fianna Fáil have won seats in both the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland, and both of these parties have established offices in Britain in order to raise funds and win additional supporters.[51]

Scholarship of identity and politics in the British Isles

Several academic perspectives are important in the politics and relations in the British isles. Important strands of scholarship include research on identity, especially Britishness and Irish identity, and studies of the major political movements, such as separatism, unionism and nationalism. The concept of post-nationalism is also a contemporary trend in studies of history, culture and politics in the isles.

The recent trend of using an archipelago perspective in scholarship of history, politics and identity was initiated by historian J. G. A. Pocock in the 1970s. He coined the term Atlantic archipelago as a replacement for British Isles, and he pressed his fellow historians to reconsider two issues linked to the future of British history. First, he urged historians of the British Isles to move away from histories of the Three Kingdoms (Scotland, Ireland, England) as separate entities,[52] and he called for studies implementing a bringing-together or conflation of these national narratives into truly integrated enterprises. Pocock proposed the term Atlantic archipelago to avoid the contested British isles. It has since become the commonplace preference of historians to treat British history in just this fashion (e.g. Hugh Kearney's The British Isles: A History of Four Nations or Norman Davies The Isles: A History).[53]

In recent times, Richard Kearney has been an important scholar in this space, through his works for example on a Postnationalist Archipelago.[54] While Kearney's work has been noted by many as important for understanding of modern Irish politics and identity, some have also argued that his approach can be applied to the archipelago as a whole: "Scholars and critics have noted the importance of Kearney's work on post-nationalism for Irish studies and politics. However, less attention has been paid to its implications for discussions and debates beyond the Irish Sea. In this context, Kearney's writings can be viewed as part of a broader intellectual landscape in which national identity, nationalism, and possibly postnationalism are at the center of political and intellectual discussions in the Isles. I say the Isles here, rather than simply Britain, because re-imagining the component parts of Britain, or more precisely the United Kingdom, entails reconfiguring the relationships in the entire archipelago."[55] Kearney's ideas and thinking were important in the lead-up to the Good Friday Agreement, and he was an early proponent of what eventually became the British-Irish Council.[56][57][58]

The University of Exeter in the UK and the Moore Institute at the National University of Ireland, Galway started in October 2010 the Atlantic Archipelago Research Project, which purports to "take an interdisciplinary view on how Britain’s post-devolution state inflects the formation of post-split Welsh, Scottish and English identities in the context of Ireland’s own experience of partition and self-rule; Consider the significance of this island grouping to the understanding of a Europe that exists in a range of configurations; from large scale political union, to provinces, dependencies, and micro-nationalist regions (such as Cornwall), each with their contribution and presence; Reconsider relations across our island grouping in light of issues regarding the management and use of the environment."[59]

References

- "Background briefing on the Crown Dependencies: Jersey, Guernsey and the Isle of Man" (PDF). Ministry of Justice, UK. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) "Government officials must never state or imply that the Crown Dependencies are part of the United Kingdom, or Great Britain or England or act on that assumption." - "House of Commons Justice Committee: Crown Dependencies: Eighth Report of Session 2009–10" (PDF). House of Commons. March 30, 2010. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) 7. The Bailiwicks of Jersey and Guernsey and the Isle of Man are Dependencies of the Crown, with Her Majesty The Queen as Sovereign.2 The Sovereign is represented in each jurisdiction by a Lieutenant Governor. Although they are proud of their British associations, the Crown Dependencies are not part of the United Kingdom and are autonomous and self-governing, with their own, independent legal, administrative and fiscal systems. The Island parliaments legislate for themselves. UK legislation and international treaties are only extended to them with their consent. It has been argued that Westminster retains a residual legislative power over the Islands in order to avoid “the impossible position of having responsibility without power”. We are not aware of any example in recent times of such a power being exercised. …

Her Majesty the Queen is Sovereign in each of the Crown Dependencies for historical reasons which are different for each Island. In each case, however, she executes her responsibilities for the Crown Dependencies on the advice of her Privy Council and her executive responsibilities are carried out by Her Majesty’s Government. Within HM Government, the Ministry of Justice is the point of contact for the Crown Dependencies, and communications in both directions are passed through its offices. Whilst this inquiry deals with the relationship between the Ministry of Justice and the Crown Dependencies, it is important to realise that their relationship is technically with the Crown and that HM Government’s responsibilities are derived from this fact. - Kavanagh, Dennis; Richards, David; Geddes, Andrew; Smith, Martin (2006), British politics, Oxford: Oxford University Press, p. 323, ISBN 9780199269792,

Although the United Kingdom is composed of four nations it is a unitary state. Laws are passed by the Westminster Parliament and by the Scottish Parliament. The state is governed from London. Any power exercised by subordinate authorities is bestowed by, and can likewise be taken away by, Parliament.

- Anthony Wilfred Bradley; Keith D. Ewing (2007), Constitutional and Administrative Law, Volume 1 (14 ed.), Harlow: Pearson Education, pp. 33, 323, ISBN 978-1405812078,

In law, the expression 'United Kingdom' refers to the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland; it does not include the Channel Islands or the Isle of Man. For the purposes of international relations, however, the Channel islands and the Isle of Man are represented by the UK government.

…

International law has the primary function of regulating the relations of independent, sovereign states with one another. For this purpose the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland is the state, with authority to act also for its dependent possessions, such as the Channel Islands, the Isle of Man and its surviving overseas territories, such as Gibraltar, none of which is a state at international law. - Ministry of Justice. "Background briefing on the Crown Dependencies: Jersey, Guernsey and the Isle of Man" (PDF).

The UK Government is responsible for defence and international representation of the Crown Dependencies. In certain circumstances, the Crown Dependencies may be authorised to conclude their own international agreements ... within the terms of Letters of Entrustment issued to their Governments under the signature of the appropriate UK Minister.

However, being responsible for the Crown Dependencies’ international representation is not limited to simply entering international agreements; it should be read to include any international or external relations whether or not they result in some internationally binding agreement. - L. Prakke; C. A. J. M. Kortmann; J. C. E. van den Brandhof (2004), Constitutional Law of 15 EU Member States, Deventer: Kluwer, p. 429, ISBN 978-9013012552,

Since 1937, Ireland has been a parliamentary republic, in which ministers appointed by the president depend on the confidence of parliament

- "Changes in the list of subdivision names and code elements" (PDF). ISO 3166-2. International Organization for Standardization. 15 December 2011. Retrieved 28 May 2012.

- "Channel Islands". Website of the British Monarchy. Retrieved 17 June 2012.

- Feldman, David (2010), English Public Law, Oxford: Oxford University Press, p. 38, ISBN 978-0199227938,

Three 'Crown dependencies' - the Bailiwicks of Jersey and Guernsey, and the Isle of Man - have a distinct constitutional position, arising from an historical association with the Crown rather than by reason of being colonies. The British Overseas Territories and the Crown dependencies are not part of the United Kingdom but the Crown as responsibility for their international affairs. The UK Parliament asserts power to legislate for them.

- "Immigration, Passports and Nationality FAQs".

- Simon Tostevin (9 July 2008). "Independence: Islanders don't want it, says Trott". Guernsey Evening Press.

- "Cities of the Isles" (PDF). Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Jesse, Neal G., Williams, Kristen P.: Identity and institutions: conflict reduction in divided societies.Publisher: SUNY Press, 2005, page 107. ISBN 0-7914-6451-2

- "Scottish government website"

- Derek Birrell (May 2012). "Intergovernmental Relations and Political Parties in Northern Ireland". The British Journal of Politics & International Relations. 14 (2): 270–284. doi:10.1111/j.1467-856X.2011.00503.x.

- Qvortrup, M & Hazell, R (1998). "The British-Irish Council: Nordic Lessons for the Council of the Isles" (PDF). University College London. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Members". British Irish Parliamentary Assembly website. Retrieved 17 June 2012.

- "Common Travel Area between Ireland and the United Kingdom". Citizens Information Board. Retrieved 12 August 2011.

- "Crown Dependencies Join Forces On Money Laundering With New "Know Your Customer" Principles". Tax-News.com. 20 December 2000.

- "Channel Isles And IoM Discuss Joint Approach To EU Tax Directive". Tax-News.com. 2 September 2003.

- "JOINT APPROACH NEEDED TO EU". Isle of Man Today. 1 Sep 2003. Archived from the original on 12 June 2013. Retrieved 21 June 2012.

- "'Positive' meeting at Inter-Island conference". Isle of Man Newspapers. 7 Sep 2007.

- "Inter-island crown dependencies meeting". IFCFeed.com. 28 September 2009.

- "Crown Dependencies Summit Held". Tax-News.com. 30 May 2012.

- "Double Tax Agreements with Guernsey and Isle of Man". 24 January 2013. Retrieved 24 January 2013.

- "Guernsey, Jersey and Isle of Man sign taxation agreement". BBC. 24 January 2013. Retrieved 24 January 2013.

- "Strand 3: British-Irish Council and intergovernmental conference". 2011-12-12. Retrieved June 21, 2012. 10. In addition to the structures provided for under this agreement, it will be open to two or more members to develop bilateral or multilateral arrangements between them. Such arrangements could include, subject to the agreement of the members concerned, mechanisms to enable consultation, co-operation and joint decision-making on matters of mutual interest; and mechanisms to implement any joint decisions they may reach. These arrangements will not require the prior approval of the BIC as a whole and will operate independently of it.

- Note: Ireland and the United Kingdom are the only sovereign states in the archipelago; thus formal bilateral state-to-state relations (i.e. treaties, formal diplomatic exchanges, etc) only occur between them. However, many sources refer to bilateral relations as being broader than just sovereign state-to-state relations, so that is the sense in which the term bilateral is used here.

- "North-South Ministerial Council: 2010 Yeirlie Din" (PDF). Armagh: North/South Ministerial Council. 2010.

- "Government Response to the Justice Select Committee's report: Crown Dependencies" (PDF). Ministry of Justice. November 2010. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) Besides informal ties, Ireland has signed formal tax agreements with all of the Crown dependencies. The UK government has called these bilateral relationships - from the source: "The Government agrees with the Committee’s views on the increased use of entrustment. We consider the system of entrustment to have worked well so far. It has enabled the Crown Dependencies to negotiate and conclude numerous tax agreements with OECD, EU and G20 countries. They have been able to build important bilateral and multi lateral international relationships and to develop reputation, profile and credibility with international partners and overarching sovereign bodies." - "Chief Minister welcomes Scottish Government Minister". March 20, 2008.

- "Scottish minister hits out at Manx scallop fishing ban". BBC. 19 November 2010.

- "Jersey represented at Lib Dems conference". States of Jersey. Retrieved 4 October 2012.

- "Deputy Chief Minister welcomes growing understanding of Guernsey at the Lib Dem Conference". States of Guernsey. Retrieved 4 October 2012.

- "Guernsey misses Labour conference due to 'limited budget'". Guernsey Evening Press. 4 October 2012. Retrieved 4 October 2012.

- "Channel Island Ministers to meet with Irish Government". States of Guernsey. Retrieved 4 October 2012.

- "Irish to close consulate in Cardiff". Wales Online. July 1, 2009.

- "Ireland Wales Programme 2007 - 2013". Retrieved May 24, 2012.

- "First Minister Alex Salmond, Statement on the 10th British Irish Council Summit". 2008-03-31. Retrieved June 19, 2012.

- "Ahern pledges closer links with Scotland". The Telegraph. 21 June 2001. Retrieved June 19, 2012.

- McWilliams, Patrick (2011-05-18). Irish-Scottish Links on Energy Study (ISLES) (PDF). All Energy 2011. Scottish Government. Retrieved 2011-11-11.

- Andrew Woodcock (20 June 2011). "'ALL-ISLANDS' ENERGY PLAN AGREED". Press Association National Newswire.

- "Isle of Man to share wind farm cost with Ireland?". Isleofman.com. June 21, 2011.

- "British Isles deal on channel Islands Renewable Energy". Indiainfoline News Service. 3 August 2011.

- "Irish Sea Region". Archived from the original on July 17, 2012. Retrieved May 24, 2012.

- "Agreement relating to the Transmission of Natural Gas through a Second Pipeline between the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland and Ireland and through a Connection to the Isle of Man" (PDF). September 24, 2004. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Northern Lighthouse Board". Retrieved June 18, 2012.

- "British shipping tax subsidies for Irish lighthouses to end". The Guardian. 29 April 2011. Retrieved June 19, 2012.

- "Nationality instructions: Volume 2".

- "Ministers 'must prepare for Jersey independence'". This is Jersey. 21 January 2010.

- "Political parties to build links with Irish in Britain". The Irish Post. 17 February 2012.

- Pocock, The Discovery of Islands, 77–93.

- Pocock, "British History: a Plea for a New Subject," 22–43 (1975); "The Field Enlarged: an Introduction," 47–57; and "The Politics of the New British History," 289–300, in The Discovery of Islands. See also "The Limits and Divisions of British History: in Search of the Unknown Subject," American Historical Review 87:2 (Apr. 1982), 311–36; "The New British History in Atlantic Perspective: an Antipodean Commentary," American Historical Review 104:2 (Apr. 1999), 490–500.

- Kearney, Richard (2006). "Chapter 1: Towards a Postnationalist Archipelago". Navigations: Collected Irish Essays, 1976-2006. Syracuse University Press. ISBN 9780815631262.

- Peter Gratton; John Panteleimon Manoussakis; Richard Kearney (2007). Peter Gratton; John Panteleimon Manoussakis (eds.). Traversing the Imaginary: Richard Kearney and the Postmodern Challenge. Northwestern University studies in phenomenology & existential philosophy. Northwestern University Press. p. 61. ISBN 9780810123786.

- Peter Gratton; John Panteleimon Manoussakis; Richard Kearney (2007). Peter Gratton; John Panteleimon Manoussakis (eds.). Traversing the Imaginary: Richard Kearney and the Postmodern Challenge. Northwestern University studies in phenomenology & existential philosophy. Northwestern University Press. pp. 61–75. ISBN 9780810123786.

- "Richard Kearney Curriculum Vitae".

- Barry Collins (Winter 2002). "The Belfast Agreement and the Nation that "Always Arrives at Its Destination."". Int'l L. Rev. (385).

- "Atlantic Archipelagos Research Project (AARP)".

Further reading

- Davies, Norman (1999). The Isles, A History. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-513442-1.

- Tompson, Richard S. E. (1986). The Atlantic archipelago: A political history of the British Isles. Lewiston, N.Y.: Mellen Press. ISBN 978-0889464551.

- Norquay, Glenda; Smyth, Gerry, eds. (2002). Across the Margins: Cultural Identity and Change in the Atlantic Archipelago. Manchester and New York: Manchester University Press. ISBN 9780719057496.