Scotland in the Middle Ages

Scotland in the Middle Ages concerns the history of Scotland from the departure of the Romans to the adoption of major aspects of the Renaissance in the early sixteenth century.

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Scotland |

|

|

|

|

By Region |

|

|

From the fifth century northern Britain was divided into a series of petty kingdoms. Of these the four most important to emerge were the Picts, the Gaels of Dál Riata, the Britons of Strathclyde and the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of Bernicia, later taken over by Northumbria. After the arrival of the Vikings in the late eighth century, Scandinavian rulers and colonies were established along parts of the coasts and in the islands.

In the ninth century the Scots and Picts combined under the House of Alpin to form a single Kingdom of Alba, with a Pictish base and dominated by Gaelic culture. After the reign of King David I in the twelfth century, the Scottish monarchs are best described as Scoto-Norman, preferring French culture to native Scottish culture. Alexander II and his son Alexander III, were able to regain the remainder of the western seaboard, cumulating the Treaty of Perth with Norway in 1266.

After being invaded and briefly occupied, Scotland re-established its independence from England under figures including William Wallace in the late thirteenth century and Robert Bruce in the fourteenth century.

In the fifteenth century under the Stewart Dynasty, despite a turbulent political history, the crown gained greater political control at the expense of independent lords and regained most of its lost territory to approximately the modern borders of the country. However, the Auld Alliance with France led to the heavy defeat of a Scottish army at the Battle of Flodden in 1513 and the death of the king James IV, which would be followed by a long minority and a period of political instability. Kingship was the major form of government, growing in sophistication in the late Middle Ages. The scale and nature of war also changed, with larger armies, naval forces and the development of artillery and fortifications.

The Church in Scotland always accepted papal authority (contrary to the implications of Celtic Christianity), introduced monasticism, and from the eleventh century embraced monastic reform, developing a flourishing religious culture that asserted its independence from English control.

Scotland grew from its base in the eastern Lowlands, to approximately its modern borders. The varied and dramatic geography of the land provided a protection against invasion, but limited central control. It also defined the largely pastoral economy, with the first burghs being created from the twelfth century. The population may have grown to a peak of a million before the arrival of the Black Death in 1350. In the early Middle Ages society was divided between a small aristocracy and larger numbers of freemen and slaves. Serfdom disappeared in the fourteenth century and there was a growth of new social groups.

The Pictish and Cumbric languages were replaced by Gaelic, Old English and later Norse, with Gaelic emerging as the major cultural language. From the eleventh century French was adopted in the court and in the late Middle Ages, Scots, derived from Old English, became dominant, with Gaelic largely confined to the Highlands. Christianity brought Latin, written culture and monasteries as centres of learning. From the twelfth century, educational opportunities widened and a growth of lay education cumulated in the Education Act 1496. Until in the fifteenth century, when Scotland gained three universities, Scots pursuing higher education had to travel to England or the continent, where some gained an international reputation. Literature survives in all the major languages present in the early Middle Ages, with Scots emerging as a major literary language from John Barbour's Brus (1375), developing a culture of poetry by court makars, and later major works of prose. Art from the early Middle Ages survives in carving, in metalwork, and elaborate illuminated books, which contributed to the development of the wider insular style. Much of the finest later work has not survived, but there are a few key examples, particularly of work commissioned in the Netherlands. Scotland had a musical tradition, with secular music composed and performed by bards and from the thirteenth century, church music increasingly influenced by continental and English forms.

Political history

Early Middle Ages

Minor kingdoms

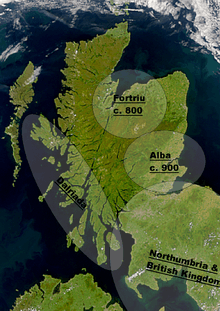

In the centuries after the departure of the Romans from Britain, four major circles of influence emerged within the borders of what is now Scotland. In the east were the Picts, whose kingdoms eventually stretched from the river Forth to Shetland. The first identifiable king to have exerted a superior and wide-ranging authority, was Bridei mac Maelchon (r. c. 550–84), whose power was based in the Kingdom of Fidach and his base was at the fort of Craig Phadrig near modern Inverness.[1] After his death leadership seems to have shifted to the Fortriu, whose lands were centred on Strathearn and Menteith and who raided along the eastern coast into modern England. Christian missionaries from Iona appear to have begun the conversion of the Picts to Christianity from 563.[2]

In the west were the Gaelic (Goidelic)-speaking people of Dál Riata with their royal fortress at Dunadd in Argyll, with close links with the island of Ireland, from which they brought with them the name Scots. In 563 a mission from Ireland under St. Columba founded the monastery of Iona off the west coast of Scotland and probably began the conversion of the region to Christianity.[2] The kingdom reached its height under Áedán mac Gabráin (r. 574–608), but its expansion was checked at the Battle of Degsastan in 603 by Æthelfrith of Northumbria.[3]

In the south was the British (Brythonic) Kingdom of Strathclyde, descendants of the peoples of the Roman influenced kingdoms of "The Old North", often named Alt Clut, the Brythonic name for their capital at Dumbarton Rock. In 642, they defeated the men of Dál Riata,[4] but the kingdom suffered a number of attacks from the Picts, and later their Northumbrian allies, between 744 and 756.[5] After this, little is recorded until Alt Clut was burnt and probably destroyed in 780, although by whom and what in what circumstances is not known.[6]

Finally, there were the English or "Angles", Germanic invaders who had overrun much of southern Britain and held the Kingdom of Bernicia, in the south-east.[7] The first English king in the historical record is Ida, who is said to have obtained the throne and the kingdom about 547.[8] Ida's grandson, Æthelfrith, united his kingdom with Deira to the south to form Northumbria around the year 604. There were changes of dynasty, and the kingdom was divided, but it was re-united under Æthelfrith's son Oswald (r. 634–42), who had converted to Christianity while in exile in Dál Riata and looked to Iona for missionaries to help convert his kingdom.[9]

Origins of the Kingdom of Alba

This situation was transformed in AD 793 when ferocious Viking raids began on monasteries like Iona and Lindisfarne, creating fear and confusion across the kingdoms of North Britain. Orkney, Shetland and the Western Isles eventually fell to the Norsemen.[10] The King of Fortriu, Eógan mac Óengusa, and the King of Dál Riata Áed mac Boanta, were among the dead in a major defeat at the hands of the Vikings in 839.[11] A mixture of Viking and Gaelic Irish settlement into south-west Scotland produced the Gall-Gaidel, the Norse Irish, from which the region gets the modern name Galloway.[12] Sometime in the ninth century the beleaguered Kingdom of Dál Riata lost the Hebrides to the Vikings, when Ketil Flatnose is said to have founded the Kingdom of the Isles.[13]

These threats may have speeded a long term process of gaelicisation of the Pictish kingdoms, which adopted Gaelic language and customs. There was also a merger of the Gaelic and Pictish crowns, although historians debate whether it was a Pictish takeover of Dál Riata, or the other way around. This culminated in the rise of Cínaed mac Ailpín (Kenneth MacAlpin) in the 840s, which brought to power the House of Alpin.[14] In AD 867 the Vikings seized Northumbria, forming the Kingdom of York;[15] three years later they stormed the Britons' fortress of Dumbarton[16] and subsequently conquered much of England except for a reduced Kingdom of Wessex,[15] leaving the new combined Pictish and Gaelic kingdom almost encircled.[17] When he died as king of the combined kingdom in 900, Domnall II (Donald II) was the first man to be called rí Alban (i.e. King of Alba).[18] The term Scotia would be increasingly be used to describe the kingdom between North of the Forth and Clyde and eventually the entire area controlled by its kings would be referred to as Scotland.[19]

High Middle Ages

Gaelic kings: Constantine II to Alexander I

The long reign (900–942/3) of Causantín (Constantine II) is often regarded as the key to formation of the Kingdom of Alba. He was later credited with bringing Scottish Christianity into conformity with the Catholic Church. After fighting many battles, his defeat at Brunanburh was followed by his retirement as a Culdee monk at St. Andrews.[20] The period between the accession of his successor Máel Coluim I (Malcolm I) and Máel Coluim mac Cináeda (Malcolm II) was marked by good relations with the Wessex rulers of England, intense internal dynastic disunity and relatively successful expansionary policies. In 945, Máel Coluim I annexed Strathclyde, where the kings of Alba had probably exercised some authority since the later ninth century, as part of an agreement with King Edmund of England.[21] This event was offset by loss of control in Moray. The reign of King Donnchad I (Duncan I) from 1034 was marred by failed military adventures, and he was defeated and killed by Macbeth, the Mormaer of Moray, who became king in 1040.[22] MacBeth ruled for 17 years before he was overthrown by Máel Coluim, the son of Donnchad, who some months later defeated Macbeth's step-son and successor Lulach to become king Máel Coluim III (Malcolm III).[23]

It was Máel Coluim III, who acquired the nickname "Canmore" (Cenn Mór, "Great Chief"), which he passed to his successors and who did most to create the Dunkeld dynasty that ruled Scotland for the following two centuries. Particularly important was his second marriage to the Anglo-Hungarian princess Margaret.[24] This marriage, and raids on northern England, prompted William the Conqueror to invade and Máel Coluim submitted to his authority, opening up Scotland to later claims of sovereignty by English kings.[25] When Malcolm died in 1093, his brother Domnall III (Donald III) succeeded him. However, William II of England backed Máel Coluim's son by his first marriage, Donnchad, as a pretender to the throne and he seized power. His murder within a few months saw Domnall restored with one of Máel Coluim sons by his second marriage, Edmund, as his heir. The two ruled Scotland until two of Edmund's younger brothers returned from exile in England, again with English military backing. Victorious, Edgar, the oldest of the three, became king in 1097.[26] Shortly afterwards Edgar and the King of Norway, Magnus Bare Legs concluded a treaty recognising Norwegian authority over the Western Isles. In practice Norse control of the Isles was loose, with local chiefs enjoying a high degree of independence. He was succeeded by his brother Alexander, who reigned 1107–24.[27]

Scoto-Norman kings: David I to Alexander III

When Alexander died in 1124, the crown passed to Margaret's fourth son David I, who had spent most of his life as an English baron. His reign saw what has been characterised as a "Davidian Revolution", by which native institutions and personnel were replaced by English and French ones, underpinning the development of later Medieval Scotland.[28][29] Members of the Anglo-Norman nobility took up places in the Scottish aristocracy and he introduced a system of feudal land tenure, which produced knight service, castles and an available body of heavily armed body of cavalry. He created an Anglo-Norman style of court, introduced the office of justicar to oversee justice, and local offices of sheriffs to administer localities. He established the first royal burghs in Scotland, granting rights to particular settlements, which led to the development of the first true Scottish towns and helped facilitate economic development as did the introduction of the first recorded Scottish coinage. He continued a process begun by his mother and brothers, of helping to establish foundations that brought the reformed monasticism based on that at Cluny. He also played a part in the organisation of diocese on lines closer to those in the rest of Western Europe.[30]

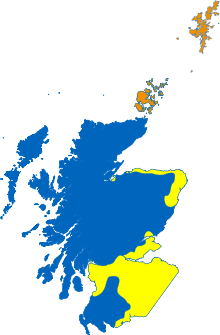

These reforms were pursued under his successors and grandchildren Malcolm IV of Scotland and William I, with the crown now passing down the main line of descent through primogeniture, leading to the first of a series of minorities.[26] The benefits of greater authority were reaped by William's son Alexander II and his son Alexander III, who pursued a policy of peace with England to expand their authority in the Highlands and Islands. By the reign of Alexander III, the Scots were in a position to annexe the remainder of the western seaboard, which they did following Haakon Haakonarson's ill-fated invasion and the stalemate of the Battle of Largs with the Treaty of Perth in 1266.[31]

Late Middle Ages

Wars of Independence: Margaret to David II

The death of King Alexander III in 1286, and then of his granddaughter and heir Margaret, Maid of Norway in 1290, left 14 rivals for succession. To prevent civil war the Scottish magnates asked Edward I of England to arbitrate, for which he extracted legal recognition that the realm of Scotland was held as a feudal dependency to the throne of England before choosing John Balliol, the man with the strongest claim, who became king in 1292.[32] Robert Bruce, 5th Lord of Annandale, the next strongest claimant, accepted this outcome with reluctance. Over the next few years Edward I used the concessions he had gained to systematically undermine both the authority of King John and the independence of Scotland.[33] In 1295 John, on the urgings of his chief councillors, entered into an alliance with France, known as the Auld Alliance.[34] In 1296 Edward invaded Scotland, deposing King John. The following year William Wallace and Andrew de Moray raised forces to resist the occupation and under their joint leadership an English army was defeated at the Battle of Stirling Bridge. For a short time Wallace ruled Scotland in the name of John Balliol as guardian of the realm. Edward came north in person and defeated Wallace at the Battle of Falkirk.[35] The English barons refuted the French-inspired papal claim to Scottish overlordship in the Barons' Letter, 1301, claiming it rather as long possessed by English kings. Wallace escaped but probably resigned as Guardian of Scotland. In 1305 he fell into the hands of the English, who executed him for treason despite the fact that he believed he owed no allegiance to England.[36]

Rivals John Comyn and Robert the Bruce, grandson of the claimant, were appointed as joint guardians in his place.[37] On 10 February 1306, Bruce participated in the murder of Comyn, at Greyfriars Kirk in Dumfries.[38] Less than seven weeks later, on 25 March, Bruce was crowned as king. However, Edward's forces overran the country after defeating Bruce's small army at the Battle of Methven.[39] Despite the excommunication of Bruce and his followers by Pope Clement V, his support slowly strengthened; and by 1314 with the help of leading nobles such as Sir James Douglas and Thomas Randolph only the castles at Bothwell and Stirling remained under English control.[40] Edward I had died in 1307. His heir Edward II moved an army north to break the siege of Stirling Castle and reassert control. Robert defeated that army at the Battle of Bannockburn in 1314, securing de facto independence.[41] In 1320 the Declaration of Arbroath, a remonstrance to the pope from the nobles of Scotland, helped convince Pope John XXII to overturn the earlier excommunication and nullify the various acts of submission by Scottish kings to English ones so that Scotland's sovereignty could be recognised by the major European dynasties. The declaration has also been seen as one of the most important documents in the development of a Scottish national identity.[42]

In 1328, Edward III signed the Treaty of Northampton acknowledging Scottish independence under the rule of Robert the Bruce.[43] However, four years after Robert's death in 1329, England once more invaded on the pretext of restoring Edward Balliol, son of John Balliol, to the Scottish throne, thus starting the Second War of Independence.[43] Despite victories at Dupplin Moor and Halidon Hill, in the face of tough Scottish resistance led by Sir Andrew Murray, the son of Wallace's comrade in arms, successive attempts to secure Balliol on the throne failed.[43] Edward III lost interest in the fate of his protege after the outbreak of the Hundred Years' War with France.[43] In 1341 David II, King Robert's son and heir, was able to return from temporary exile in France. Balliol finally resigned his claim to the throne to Edward in 1356, before retiring to Yorkshire, where he died in 1364.[44]

The Stewarts: Robert II to James IV

.jpg)

After David II's death, Robert II, the first of the Stewart kings, came to the throne in 1371. He was followed in 1390 by his ailing son John, who took the regnal name Robert III. During Robert III's reign (1390–1406), actual power rested largely in the hands of his brother, Robert Stewart, Duke of Albany.[45] After the suspicious death (possibly on the orders of the Duke of Albany) of his elder son, David, Duke of Rothesay in 1402, Robert, fearful for the safety of his younger son, the future James I, sent him to France in 1406. However, the English captured him en route and he spent the next 18 years as a prisoner held for ransom. As a result, after the death of Robert III, regents ruled Scotland: first, the Duke of Albany; and later his son Murdoch.[46]

When Scotland finally paid the ransom in 1424, James, aged 32, returned with his English bride determined to assert this authority.[45] Several members of the Albany family were executed, and he succeeded in centralising control in the hands of the crown, but at the cost of increasingly unpopularity and he was assassinated in 1437. His son James II when he came of age in 1449, continued his father's policy of weakening the great noble families, most notably taking on the powerful Black Douglas family that had come to prominence at the time of Robert I.[45] His attempt to take Roxburgh from the English in 1460 succeeded, but at the cost of his life as he was killed by an exploding artillery piece.[47]

His young son came to the throne as James III, resulting in another minority, with Robert, Lord Boyd emerging as the most important figure. In 1468 James married Margaret of Denmark, receiving the Orkney and the Shetland Islands in payment of her dowry.[48] In 1469 the King asserted his control, executing members of the Boyd family and his brothers, Alexander, Duke of Albany and John, Earl of Mar, resulting in Albany leading an English backed invasion and becoming effective ruler.[49] The English retreated, having taken Berwick for the last time in 1482, and James was able to regain power. However, the King managed to alienate the barons, former supporters, his wife and his son James. He was defeated at the Battle of Sauchieburn and killed in 1488.[50]

His successor James IV successfully ended the quasi-independent rule of the Lord of the Isles, bringing the Western Isles under effective Royal control for the first time.[45] In 1503, he married Margaret Tudor, daughter of Henry VII of England, thus laying the foundation for the seventeenth century Union of the Crowns.[51] However, in 1512 the Auld Alliance was renewed and under its terms, when the French were attacked by the English under Henry VIII the next year, James IV invaded England in support. The invasion was stopped decisively at the Battle of Flodden during which the King, many of his nobles, and a large number of ordinary troops were killed. Once again Scotland's government lay in the hands of regents in the name of the infant James V.[52]

Government

Kingship was the major form of political organisation in the Early Middle Ages, with competing minor kingdoms and fluid relationships of over and under kingdoms.[53] The primary function of these kings was as war leaders, but there were also ritual elements to kingship, evident in ceremonies of coronation.The unification of the Scots and Picts from the tenth century that produced the Kingdom of Alba, retained some of these ritual aspects in the coronation at Scone.[54] While the Scottish monarchy remained a largely itinerant institution, Scone remained one of its most important locations,[55] with Royal castles at Stirling and Perth becoming significant in the later Middle Ages before Edinburgh developed as a capital in the second half of the fifteenth century.[56] The Scottish crown grew in prestige throughout the era and adopted the conventional offices of Western European courts[57] and later elements of their ritual and grandeur.[56]

In the early period the kings of the Scots depended on the great lords of the mormaers (later earls) and Toísechs (later thanes), but from the reign of David I sheriffdoms were introduced, which allowed more direct control and gradually limited the power of the major lordships.[58] While knowledge of early systems of law is limited, justice can be seen as developing from the twelfth century onwards with local sheriff, burgh, manorial and ecclesiastical courts and offices of the justicar to oversee administration.[59] The Scots common law began to develop in this period[60] and there were attempts to systematise and codify the law and the beginnings of an educated professional body of lawyers.[61] In the Late Middle Ages major institutions of government, including the privy council and parliament developed. The council emerged as a full-time body in the fifteenth century, increasingly dominated by laymen and critical to the administration of justice. Parliament also emerged as a major legal institution, gaining an oversight of taxation and policy. By the end of the era it was sitting almost every year, partly because of the frequent minorities and regencies of the period, which may have prevented it from being sidelined by the monarchy.[62]

Warfare

In the Early Middle Ages, war on land was characterised by the use of small war-bands of household troops often engaging in raids and low level warfare.[63] The arrival of the Vikings brought a new scale of naval warfare, with rapid movement based around the Viking longship. The birlinn, which developed from the longship, became a major factor in warfare in the Highlands and Islands.[64] By the High Middle Ages, the kings of Scotland could command forces of tens of thousands of men for short periods as part of the "common army", mainly of poorly armoured spear and bowmen.[65] After the introduction of feudalism to Scotland, these forces were augmented by small numbers of mounted and heavily armoured knights.[28] Feudalism also introduced castles into the country, originally simple wooden motte-and-bailey constructions, but these were replaced in the thirteenth century with more formidable stone "enceinte" castles, with high encircling walls.[66] In the thirteenth century the threat of Scandinavian naval power subsided and the kings of Scotland were able to use naval forces to help subdue the Highlands and Islands.[31]

Scottish field armies rarely managed to stand up to the usually larger and more professional armies produced by England, but they were used to good effect by Robert I at Bannockburn in 1314 to secure Scottish independence.[67] He also made use of naval power to support his forces and began to develop a royal Scottish naval force.[68] Under the Stewart kings these forces were further augmented by specialist troops, particularly men-at-arms and archers, hired by bonds of manrent, similar to English indentures of the same period.[69] New "livery and maintenance" castles were built to house these troops[66] and castles began to be adapted to accommodate gunpowder weapons.[70] The Stewarts also adopted major innovations in continental warfare, such as longer pikes [71] and the extensive use of artillery,[72] and they built up a formidable navy.[68] However, in the early fifteenth century one of the best armed and largest Scottish armies ever assembled still met with defeat at the hands of an English army at the Battle of Flodden in 1513, which saw the destruction of a large number of ordinary troops, a large section of the nobility and the king, James IV.[52]

Religion

Christianity was probably introduced to what is now lowland Scotland from Roman soldiers stationed in the north of the province of Britannia.[73] It is presumed to have survived among the Brythonic enclaves in the south of modern Scotland, but retreated as the pagan Anglo-Saxons advanced.[74] Scotland was largely converted by Irish-Scots missions associated with figures such as St Columba from the fifth to the seventh centuries. These missions tended to found monastic institutions and collegiate churches that served large areas.[75] Partly as a result of these factors, some scholars have identified a distinctive form of Celtic Christianity, in which abbots were more significant than bishops, attitudes to clerical celibacy were more relaxed and there was some significant differences in practice with Roman Christianity, particularly the form of tonsure and the method of calculating Easter, although most of these issues had been resolved by the mid-seventh century.[76][77] After the reconversion of Scandinavian Scotland from the tenth century, Christianity under papal authority was the dominant religion of the kingdom.[78]

In the Norman period the Scottish church underwent a series of reforms and transformations. With royal and lay patronage, a clearer parochial structure based around local churches was developed.[79] Large numbers of new foundations, which followed continental forms of reformed monasticism, began to predominate and the Scottish church established its independence from England, developed a clearer diocesan structure, becoming a "special daughter of the see of Rome", but lacking leadership in the form of archbishops.[80] In the Late Middle Ages the problems of schism in the Catholic Church allowed the Scottish Crown to gain greater influence over senior appointments and two archbishoprics had been established by the end of the fifteenth century.[81] While some historians have discerned a decline of monasticism in the Late Middle Ages, the mendicant orders of friars grew, particularly in the expanding burghs, to meet the spiritual needs of the population. New saints and cults of devotion also proliferated. Despite problems over the number and quality of clergy after the Black Death in the fourteenth century, and some evidence of heresy in this period, the church in Scotland remained relatively stable before the Reformation in the sixteenth century.[81]

Geography

Modern Scotland is half the size England and Wales in area, but with its many inlets, islands and inland lochs, it has roughly the same amount of coastline at 4,000 miles. Only a fifth of Scotland is less than 60 metres above sea level. Its east Atlantic position means that it has very heavy rainfall: today about 700 cm per year in the east and over 1,000 cm in the west. This encouraged the spread of blanket peat bog, the acidity of which, combined with high level of wind and salt spray, made most of the islands treeless. The existence of hills, mountains, quicksands and marshes made internal communication and conquest extremely difficult and may have contributed to the fragmented nature of political power.[82]

The defining factor in the geography of Scotland is the distinction between the Highlands and Islands in the north and west and the Lowlands in the south and east. The highlands are further divided into the Northwest Highlands and the Grampian Mountains by the fault line of the Great Glen. The lowlands are divided into the fertile belt of the Central Lowlands and the higher terrain of the Southern Uplands, which included the Cheviot hills, over which the border with England came to run by the end of the period.[83] Some of these were further divided by mountains, major rivers and marshes.[84] The Central Lowland belt averages about 50 miles in width[85] and, because it contains most of the good quality agricultural land and has easier communications, could support most of the urbanisation and elements of conventional Medieval government.[86] However, the Southern Uplands, and particularly the Highlands were economically less productive and much more difficult to govern. This provided Scotland with a form of protection, as minor English incursions had to cross the difficult southern uplands[87] and the two major attempts at conquest by the English, under Edward I and then Edward III, were unable to penetrate the highlands, from which area potential resistance could reconquer the Lowlands.[88] However, it also made those areas problematic to govern for Scottish kings and much of the political history of the era after the wars of independence circulated around attempts to resolve problems of entrenched localism in these regions.[86]

Until the thirteenth century the borders with England were very fluid, with Northumbria being annexed to Scotland by David I, but lost under his grandson and successor Malcolm IV in 1157.[89] By the late thirteenth century when the Treaty of York (1237) and Treaty of Perth (1266) had fixed the boundaries with the Kingdom of the Scots with England and Norway respectively, its borders were close to the modern boundaries.[90] The Isle of Man fell under English control in the fourteenth century, despite several attempts to restore Scottish authority.[91] The English were able to annexe a large slice of the Lowlands under Edward III, but these losses were gradually regained, particularly while England was preoccupied with the Wars of the Roses (1455–85).[92] The dowry of the Orkney and Shetland Islands in 1468 was the last great land acquisition for the kingdom.[48] However, in 1482 Berwick, a border fortress and the largest port in Medieval Scotland, fell to the English once again, for what was to be the final change of hands.[92]

Economy and society

Economy

Having between a fifth or sixth ( 15-20 % ) of the arable or good pastoral land and roughly the same amount of coastline as England and Wales, marginal pastoral agriculture and fishing were two of the most important aspects of the Medieval Scottish economy.[93] With poor communications, in the Early Middle Ages most settlements needed to achieve a degree of self-sufficiency in agriculture.[94] Most farms were based around a family unit and used an infield and outfield system.[95] Arable farming grew in the High Middle Ages[96] and agriculture entered a period of relative boom between the thirteenth century and late fifteenth century.[97]

Unlike England, Scotland had no towns dating from Roman occupation. From the twelfth century there are records of burghs, chartered towns, which became major centres of crafts and trade.[98] and there is evidence of 55 burghs by 1296.[99] There are also Scottish coins, although English coinage probably remained more significant in trade and until the end of the period barter was probably the most common form of exchange.[100][101] Nevertheless, craft and industry remained relatively undeveloped before the end of the Middle Ages[102] and, although there were extensive trading networks based in Scotland, while the Scots exported largely raw materials, they imported increasing quantities of luxury goods, resulting in a bullion shortage and perhaps helping to create a financial crisis in the fifteenth century.[102]

Demography

There are almost no written sources from which to re-construct the demography of early Medieval Scotland. Estimates have been made of a population of 10,000 inhabitants in Dál Riata and 80–100,000 for Pictland.[103] It is likely that the 5th and 6th centuries saw higher mortality rates due to the appearance of bubonic plague, which may have reduced net population.[104] The examination of burial sites for this period like that at Hallowhill, St Andrews indicate a life expectancy of only 26–29 years.[103] The known conditions have been taken to suggest it was a high fertility, high mortality society, similar to many developing countries in the modern world, with a relatively young demographic profile, and perhaps early childbearing, and large numbers of children for women. This would have meant that there were a relatively small proportion of available workers to the number of mouths to feed. This have made it difficult to produce a surplus that would allow demographic growth and more complex societies to develop.[94] From the formation of the Kingdom of Alba in the tenth century, to before the Black Death reached the country in 1349, estimates based on the amount of farmable land, suggest that population may have grown from half a million to a million.[105] Although there is no reliable documentation on the impact of the plague, there are many anecdotal references to abandoned land in the following decades. If the pattern followed that in England, then the population may have fallen to as low as half a million by the end of the fifteenth century.[106] Compared with the situation after the redistribution of population in the later clearances and the industrial revolution, these numbers would have been relatively evenly spread over the kingdom, with roughly half living north of the Tay.[107] Perhaps ten per cent of the population lived in one of many burghs that grew up in the later Medieval period, mainly in the east and south. It has been suggested that they would have had a mean population of about 2,000, but many would be much smaller than 1,000 and the largest, Edinburgh, probably had a population of over 10,000 by the end of the era.[93]

Social structure

The organisation of society is obscure in the early part of the period, for which there are few documentary sources.[108] Kinship probably provided the primary unit of organisation and society was divided between a small aristocracy, whose rationale was based around warfare,[109] a wider group of freemen, who had the right to bear arms and were represented in law codes,[110] above a relatively large body of slaves, who may have lived beside and become clients of their owners.[94] By the thirteenth century there are sources that allow greater stratification in society to be seen, with layers including the king and a small elite of mormaers above lesser ranks of freemen and what was probably a large group of serfs, particularly in central Scotland.[111] In this period the feudalism introduced under David I meant that baronial lordships began to overlay this system, the English terms earl and thane became widespread.[112] Below the noble ranks were husbandmen with small farms and growing numbers of cottars and gresemen with more modest landholdings.[113]

The combination of agnatic kinship and feudal obligations has been seen as creating the system of clans in the Highlands in this era.[114] Scottish society adopted theories of the three estates to describe its society and English terminology to differentiate ranks.[115] Serfdom disappeared from the records in the fourteenth century[116] and new social groups of labourers, craftsmen and merchants, became important in the developing burghs. This led to increasing social tensions in urban society, but, in contrast to England and France, there was a lack of major unrest in Scottish rural society, where there was relatively little economic change.[117]

Culture

Language and culture

Modern linguists divide Celtic languages into two major groups, the P-Celtic, from which the Brythonic languages: Welsh, Breton, Cornish and Cumbric derive, and the Q-Celtic, from which come the Goidelic languages: Irish, Manx and Gaelic. The Pictish language remains enigmatic, since the Picts had no written script of their own and all that survives are place names and some isolated inscriptions in Irish ogham script.[1] Most modern linguists accept that, although the nature and unity of Pictish language is unclear, it belonged to the former group.[118] Historical sources, as well as place name evidence, indicate the ways in which the Pictish language in the north and Cumbric languages in the south were overlaid and replaced by Gaelic, Old English and later Norse in this period.[119] By the High Middle Ages the majority of people within Scotland spoke the Gaelic language, then simply called Scottish, or in Latin, lingua Scotica.[120] The Kingdom of Alba was overwhelmingly an oral society dominated by Gaelic culture. Our fuller sources for Ireland of the same period suggest that there would have been filidh, who acted as poets, musicians and historians, often attached to the court of a lord or king, and passed on their knowledge and culture in Gaelic to the next generation.[121][122]

In the Northern Isles the Norse language brought by Scandinavian occupiers and settlers evolved into the local Norn, which lingered until the end of the eighteenth century[123] and Norse may also have survived as a spoken language until the sixteenth century in the Outer Hebrides.[124] French, Flemish and particularly English became the main language of Scottish burghs, most of which were located in the south and east, an area to which Anglian settlers had already brought a form of Old English. In the later part of the twelfth century, the writer Adam of Dryburgh described lowland Lothian as "the Land of the English in the Kingdom of the Scots".[125] At least from the accession of David I, Gaelic ceased to be the main language of the royal court and was probably replaced by French, as evidenced by reports from contemporary chronicles, literature and translations of administrative documents into the French language. After this "de-gallicisation" of the Scottish court, a less highly regarded order of bards took over the functions of the filidh and they would continue to act in a similar role in the Highlands and Islands into the eighteenth century. They often trained in bardic schools, of which a few, like the one run by the MacMhuirich dynasty, who were bards to the Lord of the Isles,[126] existed in Scotland and a larger number in Ireland, until they were suppressed from the seventeenth century.[122] Members of bardic schools were trained in the complex rules and forms of Gaelic poetry.[127] Much of their work was never written down and what survives was only recorded from the sixteenth century.[121]

In the late Middle Ages, Middle Scots, often simply called English, became the dominant language of the country. It was derived largely from Old English, with the addition of elements from Gaelic and French. Although resembling the language spoken in northern England, it became a distinct dialect from the late fourteenth century onwards.[127] It began to be adopted by the ruling elite as they gradually abandoned French. By the fifteenth century it was the language of government, with acts of parliament, council records and treasurer's accounts almost all using it from the reign of James I onwards. As a result, Gaelic, once dominant north of the Tay, began a steady decline.[127] Lowland writers began to treat Gaelic as a second class, rustic and even amusing language, helping to frame attitudes towards the highlands and to create a cultural gulf with the lowlands.[127]

Education

The establishment of Christianity brought Latin to Scotland as a scholarly and written language. Monasteries served as major repositories of knowledge and education, often running schools and providing a small educated elite, who were essential to create and read documents in a largely illiterate society.[128] In the High Middle Ages new sources of education arose, with song and grammar schools. These were usually attached to cathedrals or a collegiate church and were most common in the developing burghs. By the end of the Middle Ages grammar schools could be found in all the main burghs and some small towns. Early examples including the High School of Glasgow in 1124 and the High School of Dundee in 1239.[129] There were also petty schools, more common in rural areas and providing an elementary education.[130] Some monasteries, like the Cistercian abbey at Kinloss, opened their doors to a wider range of students.[130] The number and size of these schools seems to have expanded rapidly from the 1380s. They were almost exclusively aimed at boys, but by the end of the fifteenth century, Edinburgh also had schools for girls, sometimes described as "sewing schools", and probably taught by lay women or nuns.[129][130] There was also the development of private tuition in the families of lords and wealthy burghers.[129] The growing emphasis on education cumulated with the passing of the Education Act 1496, which decreed that all sons of barons and freeholders of substance should attend grammar schools to learn "perfyct Latyne". All this resulted in an increase in literacy, but which was largely concentrated among a male and wealthy elite,[129] with perhaps 60 per cent of the nobility being literate by the end of the period.[131]

Until the fifteenth century, those who wished to attend university had to travel to England or the continent, and just over a 1,000 have been identified as doing so between the twelfth century and 1410.[132] Among these the most important intellectual figure was John Duns Scotus, who studied at Oxford, Cambridge and Paris and probably died at Cologne in 1308, becoming a major influence on late Medieval religious thought.[133] After the outbreak of the Wars of Independence, with occasional exceptions under safe conduct, English universities were closed to Scots and continental universities became more significant.[132] Some Scottish scholars became teachers in continental universities. At Paris this included John De Rate and Walter Wardlaw in the 1340s and 1350s, William de Tredbrum in the 1380s and Laurence de Lindores in the early 1500s.[132] This situation was transformed by the founding of the University of St Andrews in 1413, the University of Glasgow in 1450 and the University of Aberdeen in 1495.[129] Initially these institutions were designed for the training of clerics, but they would increasingly be used by laymen who would begin to challenge the clerical monopoly of administrative post in the government and law. Those wanting to study for second degrees still needed to go elsewhere and Scottish scholars continued to visit the continent and English universities reopened to Scots in the late fifteenth century.[132] The continued movement to other universities produced a school of Scottish nominalists at Paris in the early sixteenth century, of which John Mair was probably the most important figure. He had probably studied at a Scottish grammar school, then Cambridge, before moving to Paris, where he matriculated in 1493. By 1497 the humanist and historian Hector Boece, born in Dundee and who had studied at Paris, returned to become the first principal at the new university of Aberdeen.[132] These international contacts helped integrate Scotland into a wider European scholarly world and would be one of the most important ways in which the new ideas of humanism were brought into Scottish intellectual life.[131]

Literature

Much of the earliest Welsh literature was actually composed in or near the country now called Scotland, in the Brythonic speech, from which Welsh would be derived, include The Gododdin and the Battle of Gwen Ystrad.[134] There are also religious works in Gaelic including the Elegy for St Columba by Dallan Forgaill, c. 597 and "In Praise of St Columba" by Beccan mac Luigdech of Rum, c. 677.[135] In Latin they include a "Prayer for Protection" (attributed to St Mugint), c. mid-sixth century and Altus Prosator ("The High Creator", attributed to St Columba), c. 597.[136] In Old English there is The Dream of the Rood, from which lines are found on the Ruthwell Cross, making it the only surviving fragment of Northumbrian Old English from early Medieval Scotland.[137] Before the reign of David I, the Scots possessed a flourishing literary elite that produced texts in both Gaelic and Latin, a tradition that survived in the Highlands into the thirteenth century.[138] It is possible that more Middle Irish literature was written in Medieval Scotland than is often thought, but has not survived because the Gaelic literary establishment of eastern Scotland died out before the fourteenth century.[139] In the thirteenth century, French flourished as a literary language, and produced the Roman de Fergus, the earliest piece of non-Celtic vernacular literature to survive from Scotland.[140]

The first surviving major text in Early Scots literature is John Barbour's Brus (1375), composed under the patronage of Robert II and telling the story in epic poetry of Robert I's actions before the English invasion till the end of the war of independence.[141] Much Middle Scots literature was produced by makars, poets with links to the royal court, which included James I (who wrote The Kingis Quair). Many of the makars had a university education and so were also connected with the Kirk. However, Dunbar's Lament for the Makaris (c.1505) provides evidence of a wider tradition of secular writing outside of Court and Kirk, now largely lost.[142] Before the advent of printing in Scotland, writers such as Robert Henryson, William Dunbar, Walter Kennedy and Gavin Douglas have been seen as leading a golden age in Scottish poetry.[127] In the late fifteenth century, Scots prose also began to develop as a genre. Although there are earlier fragments of original Scots prose, such as the Auchinleck Chronicle,[143] the first complete surviving work includes John Ireland's The Meroure of Wyssdome (1490).[144] There were also prose translations of French books of chivalry that survive from the 1450s, including The Book of the Law of Armys and the Order of Knychthode and the treatise Secreta Secetorum, an Arabic work believed to be Aristotle's advice to Alexander the Great.[127] The landmark work in the reign of James IV was Gavin Douglas's version of Virgil's Aeneid, the Eneados, which was the first complete translation of a major classical text in an Anglian language, finished in 1513, but overshadowed by the disaster at Flodden.[127]

Art

In the early middles ages, there were distinct material cultures evident in the different linguistic groups, federations and kingdoms within what is now Scotland. Pictish art can be seen in the extensive survival of carved stones, particularly in the north and east of the country, which hold a variety of recurring images and patterns, as at Dunrobin (Sutherland) and Aberlemno stones (Angus).[145] It can also be seen in elaborate metal work that largely survives in buried hordes like the St Ninian's Isle Treasure.[146] Irish-Scots art from the Kingdom of Dál Riata is much more difficult to identify, but may include items like the Hunterston brooch, which with other items like the Monymusk Reliquary, suggest that Dál Riata was one of the places, as a crossroads between cultures, where the Insular style developed.[147] Insular art is the name given to the common style that developed in Britain and Ireland after the conversion of the Picts and the cultural assimilation of Pictish culture into that of the Scots and Angles,[148] and which became highly influential in continental Europe, contributing to the development of Romanesque and Gothic styles.[149] It can be seen in elaborate jewellery, often making extensive use of semi-precious stones,[150] in the heavily carved High crosses found most frequently in the Highlands and Islands, but distributed across the country[151] and particularly in the highly decorated illustrated manuscripts such as the Book of Kells, which may have been begun, or wholly created on Iona. The finest era of the style was brought to an end by the disruption to monastic centres and aristocratic life of the Viking raids in the late eighth century.[152]

Scotland adopted the Romanesque in the late twelfth century, retaining and reviving elements of its style after the Gothic had become dominant elsewhere from the thirteenth century.[153] Much of the best Scottish artwork of the High and Late Middle Ages was either religious in nature or realised in metal and woodwork, and has not survived the impact of time and of the Reformation.[154] However, examples of sculpture are extant as part of church architecture, including evidence of elaborate church interiors like the sacrament houses at Deskford and Kinkell[155] and the carvings of the seven deadly sins at Rosslyn Chapel.[156] From the thirteenth century, there are relatively large numbers of monumental effigies like the elaborate Douglas tombs in the town of Douglas.[157] Native craftsmanship can be seen in items like the Bute mazer and the Savernake Horn, and more widely in the large number of high quality seals that survive from the mid thirteenth century onwards.[154] Visual illustration can be seen in the illumination of charters,[158] and occasional survivals like the fifteenth century Doom painting at Guthrie.[159] Surviving copies of individual portraits are relatively crude, but more impressive are the works or artists commissioned from the continent, particularly the Netherlands, including Hugo van Der Goes's altarpiece for the Trinity College Church in Edinburgh and the Hours of James IV of Scotland.[160]

Architecture

Medieval vernacular architecture utilised local building materials, including cruck constructed houses, turf walls and clay, with a heavy reliance on stone.[161] As burghs developed there were more sophisticated houses for the nobles, burgesses and other inhabitants.[100] By the end of the period some were stone built with slate roofs or tiles.[162] Medieval parish church architecture was typically simpler than in England, with many churches remaining simple oblongs, without transepts and aisles, and often without towers.[155] From the eleventh century there were influences from English and continental European designs and grander ecclesiastical buildings were built in the Romanesque style, as can be seen at Dunfermline Abbey and Elgin Cathedral,[163] and later the Gothic style as at Glasgow Cathedral and in the rebuilding of Melrose Abbey.[160] From the early fifteenth century the introduction of Renaissance styles included the selective return of Romanesque forms, as in the nave of Dunkeld Cathedral and in the chapel of Bishop Elphinstone's Kings College, Aberdeen (1500–09).[164] Many of the motte and bailey castles introduced into Scotland with feudalism in the twelfth century and the castles "enceinte", with a high embattled curtain wall that replaced those still in occupation, were slighted during the Wars of Independence. In the late Middle Ages new castles were built, some on a grander scale as "livery and maintenance" castles, to house retained troops.[66] Gunpowder weaponry fundamentally altered the nature of castle architecture, with existing castles being adapted to allow the use of gunpowder weapons by the incorporation of "keyhole" gun ports, platforms to mount guns and walls being adapted to resist bombardment. Ravenscraig, Kirkcaldy, begun about 1460, is probably the first castle in the British Isles to be built as an artillery fort, incorporating "D-shape" bastions that would better resist cannon fire and on which artillery could be mounted.[70] The largest number of late medieval fortifications in Scotland built by nobles were of the tower house design.[165][166] primarily aimed to provide protection against smaller raiding parties, rather than a major siege.[167] Extensive building and rebuilding of royal palaces in the Renaissance style probably began under James III and accelerated under James IV. Linlithgow was first constructed under James I, under the direction of master of work John de Waltoun and was referred to as a palace, apparently the first use of this term in the country, from 1429. This was extended under James III and began to correspond to a fashionable quadrangular, corner-towered Italian signorial palace, combining classical symmetry with neo-chivalric imagery.[168]

Music

In the late twelfth century, Giraldus Cambrensis noted that "in the opinion of many, Scotland not only equals its teacher, Ireland, but indeed greatly outdoes it and excels her in musical skill". He identified the Scots as using the cithara, tympanum and chorus, although what exactly these instruments were is unclear.[169] Bards probably accompanied their poetry on the harp, and can also be seen in records of the Scottish courts throughout the Medieval period.[170] Scottish church music from the thirteenth century was increasingly influenced by continental developments, with figures like the musical theorist Simon Tailler studying in Paris, before returned to Scotland where he introduced several reforms of church music.[171] Scottish collections of music like the thirteenth century 'Wolfenbüttel 677', which is associated with St Andrews, contain mostly French compositions, but with some distinctive local styles.[171] The captivity of James I in England from 1406 to 1423, where he earned a reputation as a poet and composer, may have led him to take English and continental styles and musicians back to the Scottish court on his release.[171] In the late fifteenth century a series of Scottish musicians trained in the Netherlands before returning home, including John Broune, Thomas Inglis and John Fety, the last of whom became master of the song school in Aberdeen and then Edinburgh, introducing the new five-fingered organ playing technique.[172] In 1501 James IV refounded the Chapel Royal within Stirling Castle, with a new and enlarged choir and it became the focus of Scottish liturgical music. Burgundian and English influences were probably reinforced when Henry VII's daughter Margaret Tudor married James IV in 1503.[173]

National identity

In the High Middle Ages the word "Scot" was only used by Scots to describe themselves to foreigners, amongst whom it was the most common word. They called themselves Albanach or simply Gaidel. Both "Scot" and Gaidel were ethnic terms that connected them to the majority of the inhabitants of Ireland. At the beginning of the thirteenth century, the author of De Situ Albanie noted that: "The name Arregathel [Argyll] means margin of the Scots or Irish, because all Scots and Irish are generally called 'Gattheli'."[174] Scotland came to possess a unity which transcended Gaelic, French and Germanic ethnic differences and by the end of the period, the Latin, French and English word "Scot" could be used for any subject of the Scottish king. Scotland's multilingual Scoto-Norman monarchs and mixed Gaelic and Scoto-Norman aristocracy all became part of the "Community of the Realm", in which ethnic differences were less divisive than in Ireland and Wales.[175] This identity was defined in opposition to English attempts to annexe the country and as a result of social and cultural changes. The resulting antipathy towards England dominated Scottish foreign policy well into the fifteenth century, making it extremely difficult for Scottish kings like James III and James IV to pursue policies of peace towards their southern neighbour.[176] In particular the Declaration of Arbroath asserted the ancient distinctiveness of Scotland in the face of English aggression, arguing that it was the role of the king to defend the independence of the community of Scotland. This document has been seen as the first "nationalist theory of sovereignty".[177]

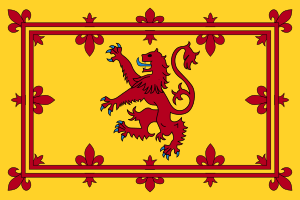

The adoption of Middle Scots by the aristocracy has been seen as building a shared sense of national solidarity and culture between rulers and ruled, although the fact that north of the Tay Gaelic still dominated may have helped widen the cultural divide between highlands and lowlands.[178] The national literature of Scotland created in the late medieval period employed legend and history in the service of the crown and nationalism, helping to foster a sense of national identity, at least within its elite audience. The epic poetic history of the Brus and Wallace helped outline a narrative of united struggle against the English enemy. Arthurian literature differed from conventional versions of the legend by treating Arthur as a villain and Mordred, the son of the king of the Picts, as a hero.[178] The origin myth of the Scots, systematised by John of Fordun (c. 1320-c. 1384), traced their beginnings from the Greek prince Gathelus and his Egyptian wife Scota, allowing them to argue superiority over the English, who claimed their descent from the Trojans, who had been defeated by the Greeks.[177] The image of St. Andrew, martyred while bound to an X-shaped cross, first appeared in the Scotland during the reign of William I and was again depicted on seals used during the late thirteenth century; including on one particular example used by the Guardians of Scotland, dated 1286.[179] Use of a simplified symbol associated with Saint Andrew, the saltire, has its origins in the late fourteenth century; the Parliament of Scotland decreed in 1385 that Scottish soldiers should wear a white Saint Andrew's Cross on their person, both in front and behind, for the purpose of identification. Use of a blue background for the Saint Andrew's Cross is said to date from at least the fifteenth century.[180] The earliest reference to the Saint Andrew's Cross as a flag is to be found in the Vienna Book of Hours, circa 1503.[181]

Notes

- J. Haywood, The Celts: Bronze Age to New Age (London: Pearson Education, 2004), ISBN 0-582-50578-X, p. 116.

- A. P. Smyth, Warlords and Holy Men: Scotland AD 80–1000 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1989), ISBN 0-7486-0100-7, pp. 43–6.

- A. Woolf, From Pictland to Alba: 789 – 1070 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2007), ISBN 0-7486-1234-3, pp. 57–67.

- A. Macquarrie, "The kings of Strathclyde, c. 400–1018", in G. W. S. Barrow, A. Grant and K. J. Stringer, eds, Medieval Scotland: Crown, Lordship and Community (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1998), ISBN 0-7486-1110-X, p. 8.

- A. Williams and A. P. Smyth, eds, A Biographical Dictionary of Dark Age Britain: England, Scotland, and Wales, c. 500-c. 1050 (London: Routledge, 1991), ISBN 1-85264-047-2, p. 106.

- A. Gibb, Glasgow, the Making of a City (London: Routledge, 1983), ISBN 0-7099-0161-5, p. 7.

- J. R. Maddicott and D. M. Palliser, eds, The Medieval State: Essays Presented to James Campbell (London: Continuum, 2000), ISBN 1-85285-195-3, p. 48.

- B. Yorke, Kings and Kingdoms of Early Anglo-Saxon England (London: Routledge, 2002), ISBN 0-203-44730-1, pp. 75–7.

- B. Yorke, Kings and Kingdoms of Early Anglo-Saxon England (London: Routledge, 2002), ISBN 0-203-44730-1, p. 78.

- W. E. Burns, A Brief History of Great Britain (Infobase Publishing, 2009), ISBN 0-8160-7728-2, pp. 44–5.

- R. Mitchison, A History of Scotland (London: Routledge, 3rd edn., 2002), ISBN 0-415-27880-5, p. 10.

- F. D. Logan, The Vikings in History (London, Routledge, 2nd edn., 1992), ISBN 0-415-08396-6, p. 49.

- R. Mitchison, A History of Scotland (London: Routledge, 3rd edn., 2002), ISBN 0-415-27880-5, p. 9.

- B. Yorke, The Conversion of Britain: Religion, Politics and Society in Britain c.600–800 (Pearson Education, 2006), ISBN 0-582-77292-3, p. 54.

- D. W. Rollason, Northumbria, 500–1100: Creation and Destruction of a Kingdom (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003), ISBN 0-521-81335-2, p. 212.

- C. A. Snyder, The Britons (Wiley-Blackwell, 2003), ISBN 0-631-22260-X, p. 220.

- J. Hearn, Claiming Scotland: National Identity and Liberal Culture (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2000), ISBN 1-902930-16-9, p. 100.

- A. O. Anderson, Early Sources of Scottish History, A.D. 500 to 1286 (General Books LLC, 2010), , vol. i, ISBN 1-152-21572-8, p. 395.

- B. Webster, Medieval Scotland: the Making of an Identity (St. Martin's Press, 1997), ISBN 0-333-56761-7, p. 22.

- A. Woolf, From Pictland to Alba: 789 – 1070 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2007), ISBN 0-7486-1234-3, p. 128.

- B. T. Hudson, Kings of Celtic Scotland (Westport: Greenhill 1994), ISBN 0-313-29087-3, pp. 95–6.

- B. T. Hudson, Kings of Celtic Scotland (Westport: Greenhill 1994), ISBN 0-313-29087-3, p. 124.

- J. D. Mackie, A History of Scotland (London: Pelican, 1964). p. 43.

- A. A. M. Duncan, Scotland: The Making of the Kingdom, The Edinburgh History of Scotland, Volume 1 (Edinburgh: Mercat Press,1989), p. 119.

- A. A. M. Duncan, Scotland: The Making of the Kingdom, The Edinburgh History of Scotland, Volume 1 (Edinburgh: Mercat Press,1989), p. 120.

- B. Webster, Medieval Scotland: the Making of an Identity (St. Martin's Press, 1997), ISBN 0-333-56761-7, pp. 23–4.

- A. Forte, R. D. Oram and F. Pedersen, Viking Empires (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005), ISBN 0-521-82992-5, p. 238.

- G. W. S. Barrow, "David I of Scotland: The Balance of New and Old", in G. W. S. Barrow, ed., Scotland and Its Neighbours in the Middle Ages (London, 1992), pp. 9–11 pp. 9–11.

- M. Lynch, Scotland: A New History (Random House, 2011), ISBN 1-4464-7563-8, p. 80.

- B. Webster, Medieval Scotland: the Making of an Identity (St. Martin's Press, 1997), ISBN 0-333-56761-7, pp. 29–37.

- A. Macquarrie, Medieval Scotland: Kinship and Nation (Thrupp: Sutton, 2004), ISBN 0-7509-2977-4, p. 153.

- R. Mitchison, A History of Scotland (London: Routledge, 3rd edn., 2002), ISBN 0-415-27880-5, p. 40.

- R. Mitchison, A History of Scotland (London: Routledge, 3rd edn., 2002), ISBN 0-415-27880-5, p. 42.

- N. Macdougall, An Antidote to the English: the Auld Alliance, 1295–1560 (Tuckwell Press, 2001), p. 9.

- R. Mitchison, A History of Scotland (London: Routledge, 3rd edn., 2002), ISBN 0-415-27880-5, pp. 43–4.

- A. Tuck, Crown and Nobility: England 1272–1461 (London: Wiley-Blackwell, 2nd edn., 1999), ISBN 0-631-21466-6, p. 31.

- David R. Ross, On the Trail of Robert the Bruce (Dundurn Press Ltd., 1999), ISBN 0-946487-52-9, p. 21.

- Hugh F. Kearney, The British Isles: a History of Four Nations (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2nd edn., 2006), ISBN 0-521-84600-5, p. 116.

- G. W. S. Barrow, Robert Bruce (Berkeley CA.: University of California Press, 1965), p. 216.

- G. W. S. Barrow, Robert Bruce (Berkeley CA.: University of California Press, 1965), p. 273.

- M. Brown, Bannockburn: the Scottish War and the British Isles, 1307–1323 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2008), ISBN 0-7486-3333-2.

- M. Brown, The Wars of Scotland, 1214–1371 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2004), ISBN 0-7486-1238-6, p. 217.

- M. H. Keen, England in the Later Middle Ages: a Political History (London: Routledge, 2nd edn., 2003), ISBN 0-415-27293-9, pp. 86–8.

- P. Armstrong, Otterburn 1388: Bloody Border Conflict (London: Osprey Publishing, 2006), ISBN 1-84176-980-0, p. 8.

- S. H. Rigby, A Companion to Britain in the Later Middle Ages (Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 2003), ISBN 0-631-21785-1, pp. 301–2.

- A. D. M. Barrell, Medieval Scotland (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000), ISBN 0-521-58602-X, pp. 151–4.

- A. D. M. Barrell, Medieval Scotland (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000), ISBN 0-521-58602-X, pp. 160–9.

- J. Wormald, Court, Kirk, and Community: Scotland, 1470–1625 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1991), ISBN 0-7486-0276-3, p. 5.

- A. D. M. Barrell, Medieval Scotland (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000), ISBN 0-521-58602-X, pp. 171–2.

- C. J. Drees, The Late Medieval Age of Crisis and Renewal, 1300–1500 (London: Greenwood, 2001), ISBN 0-313-30588-9, pp. 244–5.

- Roger A. Mason, Scots and Britons: Scottish political thought and the union of 1603 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994), ISBN 0-521-42034-2, p. 162.

- G. Menzies The Scottish Nation (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2002), ISBN 1-902930-38-X, p. 179.

- B. Yorke, "Kings and kingship", in P. Stafford, ed., A Companion to the Early Middle Ages: Britain and Ireland, c.500-c.1100 (Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell, 2009), ISBN 1-4051-0628-X, pp. 76–90.

- B. Webster, Medieval Scotland: the Making of an Identity (St. Martin's Press, 1997), ISBN 0-333-56761-7, pp. 45–7.

- P. G. B. McNeill and Hector L. MacQueen, eds, Atlas of Scottish History to 1707 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1996), pp. 159–63.

- J. Wormald, Court, Kirk, and Community: Scotland, 1470–1625 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1991), ISBN 0-7486-0276-3, pp. 14–15.

- N. H. Reid, "Crown and Community under Robert I", in G. W. S. Barrow, A. Grant and K. J. Stringer, eds, Medieval Scotland: Crown, Lordship and Community (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1998), ISBN 0-7486-1110-X, p. 221.

- P. G. B. McNeill and Hector L. MacQueen, eds, Atlas of Scottish History to 1707 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1996), pp. 191–4.

- K. Reid and R. Zimmerman, A History of Private Law in Scotland: I. Introduction and Property (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000), ISBN 0-19-829941-9, pp. 24–82.

- D. H. S. Sellar, "Gaelic Laws and Institutions", in M. Lynch, ed., The Oxford Companion to Scottish History (New York, 2001), pp. 381–82.

- K. Reid and R. Zimmerman, A History of Private Law in Scotland: I. Introduction and Property (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000), ISBN 0-19-829941-9, p. 66.

- J. Wormald, Court, Kirk, and Community: Scotland, 1470–1625 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1991), ISBN 0-7486-0276-3, pp. 21–3.

- L. Alcock, Kings and Warriors, Craftsmen and Priests in Northern Britain AD 550–850 (Edinburgh: Society of Antiquaries of Scotland), ISBN 0-903903-24-5, pp. 248–9.

- N. A. M. Rodger, The Safeguard of the Sea: A Naval History of Britain. Volume One 660–1649 (London: Harper, 1997) pp. 13–14.

- K. J. Stringer, The Reign of Stephen: Kingship, Warfare, and Government in Twelfth-Century England (Psychology Press, 1993), ISBN 0-415-01415-8, pp. 30–1.

- T. W. West, Discovering Scottish Architecture (Botley: Osprey, 1985), ISBN 0-85263-748-9, p. 21.

- D. M. Barrell, Medieval Scotland (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000), ISBN 0-521-58602-X, p. 108.

- J. Grant, "The Old Scots Navy from 1689 to 1710", Publications of the Navy Records Society, 44 (London: Navy Records Society, 1913-4), pp. i–xii.

- M. Brown, The Wars of Scotland, 1214–1371 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2004), ISBN 0-7486-1238-6, p. 58.

- T. W. West, Discovering Scottish Architecture (Botley: Osprey, 1985), ISBN 0-85263-748-9, p. 27.

- J. Cooper, Scottish Renaissance Armies 1513–1550 (Botley: Osprey, 2008), ISBN 1-84603-325-X, p. 23.

- D. H. Caldwell, "The Scots and guns", in A. King and M. A. Penman, eds, England and Scotland in the Fourteenth Century: New Perspectives (Boydell & Brewer, 2007), ISBN 1-84383-318-2, pp. 60–72.

- B. Cunliffe, The Ancient Celts (Oxford, 1997), ISBN 0-14-025422-6, p. 184.

- O. Davies, Celtic Spirituality (Paulist Press, 1999), ISBN 0-8091-3894-8, p. 21.

- O. Clancy, "The Scottish provenance of the 'Nennian' recension of Historia Brittonum and the Lebor Bretnach " in: S. Taylor (ed.), Picts, Kings, Saints and Chronicles: A Festschrift for Marjorie O. Anderson (Dublin: Four Courts, 2000), pp. 95–6 and A. P. Smyth, Warlords and Holy Men: Scotland AD 80–1000 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1989), ISBN 0-7486-0100-7, pp. 82–3.

- C. Evans, "The Celtic Church in Anglo-Saxon times", in J. D. Woods, D. A. E. Pelteret, The Anglo-Saxons, synthesis and achievement (Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 1985), ISBN 0-88920-166-8, pp. 77–89.

- C. Corning, The Celtic and Roman Traditions: Conflict and Consensus in the Early Medieval Church (Macmillan, 2006), ISBN 1-4039-7299-0.

- A. Macquarrie, Medieval Scotland: Kinship and Nation (Thrupp: Sutton, 2004), ISBN 0-7509-2977-4, pp. 67–8.

- A. Macquarrie, Medieval Scotland: Kinship and Nation (Thrupp: Sutton, 2004), ISBN 0-7509-2977-4, pp. 109–117.

- P. J. Bawcutt and J. H. Williams, A Companion to Medieval Scottish Poetry (Woodbridge: Brewer, 2006), ISBN 1-84384-096-0, pp. 26–9.

- J. Wormald, Court, Kirk, and Community: Scotland, 1470–1625 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1991), ISBN 0-7486-0276-3, pp. 76–87.

- C. Harvie, Scotland: a Short History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002), ISBN 0-19-210054-8, pp. 10–11.

- R. Mitchison, A History of Scotland (London: Routledge, 3rd edn., 2002), ISBN 0-415-27880-5, p. 2.

- B. Webster, Medieval Scotland: the Making of an Identity (St. Martin's Press, 1997), ISBN 0-333-56761-7, pp. 9–20.

- World and Its Peoples (London: Marshall Cavendish), ISBN 0-7614-7883-3, p. 13.

- J. Wormald, Court, Kirk, and Community: Scotland, 1470–1625 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1991), ISBN 0-7486-0276-3, pp. 39–40.

- A. G. Ogilvie, Great Britain: Essays in Regional Geography (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1952), p. 421.

- R. R. Sellmen, Medieval English Warfare (London: Taylor & Francis, 1964), p. 29.

- R. R. Davies, The First English Empire: Power and Identities in the British Isles, 1093–1343 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000), ISBN 0-19-820849-9, p. 64.

- W. P. L. Thomson, The New History of Orkney (Edinburgh: Birlinn, 2008), ISBN 1-84158-696-X, p. 204.

- A. Grant and K. J. Stringer, eds, Uniting the Kingdom?: the Making of British History (London: Routledge, 1995), ISBN 0-415-13041-7, p. 101.

- P. J. Bawcutt and J. H. Williams, A Companion to Medieval Scottish Poetry (Woodbridge: Brewer, 2006), ISBN 1-84384-096-0, pp. 21.

- E. Gemmill and N. J. Mayhew, Changing Values in Medieval Scotland: a Study of Prices, Money, and Weights and Measures (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995), ISBN 0-521-47385-3, pp. 8–10.

- A. Woolf, From Pictland to Alba: 789 – 1070 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2007), ISBN 0-7486-1234-3, pp. 17–20.

- H. P. R. Finberg, The Formation of England 550–1042 (London: Paladin, 1974), ISBN 978-0-586-08248-5, p. 204.

- G. W. S. Barrow, Kingship and Unity: Scotland 1000–1306 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1989), ISBN 0-7486-0104-X, p. 12.

- S. H. Rigby, ed., A Companion to Britain in the Later Middle Ages (Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 2003), ISBN 0-631-21785-1, pp. 111–6.

- G. W. S. Barrow, Kingship and Unity: Scotland 1000–1306 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1989), ISBN 0-7486-0104-X, p. 98.

- B. Webster, Medieval Scotland: the Making of an Identity (St. Martin's Press, 1997), ISBN 0-333-56761-7, pp. 122–3.

- A. MacQuarrie, Medieval Scotland: Kinship and Nation (Thrupp: Sutton, 2004), ISBN 0-7509-2977-4, pp. 136–40.

- K. J. Stringer, "The Emergence of a Nation-State, 1100–1300", in J. Wormald, ed., Scotland: A History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005), ISBN 0-19-820615-1, pp. 38–76.

- J. Wormald, Court, Kirk, and Community: Scotland, 1470–1625 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1991), ISBN 0-7486-0276-3, pp. 41–55.

- L. R. Laing, The Archaeology of Celtic Britain and Ireland, c. AD 400–1200 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006), ISBN 0-521-54740-7, pp. 21–2.

- P. Fouracre and R. McKitterick, eds, The New Cambridge Medieval History: c. 500-c. 700 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005), ISBN 0-521-36291-1, p. 234.

- R. E. Tyson, "Population Patterns", in M. Lynch, ed., The Oxford Companion to Scottish History (New York, 2001), pp. 487–8.

- S. H. Rigby, ed., A Companion to Britain in the Later Middle Ages (Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 2003), ISBN 0-631-21785-1, pp. 109–11.

- J. Wormald, Court, Kirk, and Community: Scotland, 1470–1625 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1991), ISBN 0-7486-0276-3, p. 61.

- D. E. Thornton, "Communities and kinship", in P. Stafford, ed., A Companion to the Early Middle Ages: Britain and Ireland, c.500-c.1100 (Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell, 2009), ISBN 1-4051-0628-X, pp. 98.

- C. Haigh, The Cambridge Historical Encyclopedia of Great Britain and Ireland (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990), ISBN 0-521-39552-6, pp. 82–4.

- J. T. Koch, Celtic Culture: a Historical Encyclopedia (Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2006), ISBN 1-85109-440-7, p. 369.

- A. Grant, "Thanes and Thanages, from the eleventh to the fourteenth centuries" in A. Grant and K. Stringer, eds., Medieval Scotland: Crown, Lordship and Community, Essays Presented to G. W. S. Barrow (Edinburgh University Press: Edinburgh, 1993), ISBN 0-7486-1110-X, p. 42.

- A. Grant, "Scotland in the Central Middle Ages", in A. MacKay and D. Ditchburn (eds), Atlas of Medieval Europe (Routledge: London, 1997), ISBN 0-415-12231-7, p. 97.

- G. W. S. Barrow, "Scotland, Wales and Ireland in the twelfth century", in D. E. Luscombe and J. Riley-Smith, eds, The New Cambridge Medieval History, Volume IV. 1024-c. 1198, part 2 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995), ISBN 0-521-41411-3, p. 586.

- G. W. S. Barrow, Robert Bruce (Berkeley CA.: University of California Press, 1965), p. 7.

- D. E. R. Wyatt, "The provincial council of the Scottish church", in A. Grant and K. J. Stringer, Medieval Scotland: Crown, Lordship and Community (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1998), ISBN 0-7486-1110-X, p. 152.

- J. Goodacre, State and Society in Early Modern Scotland (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999), ISBN 0-19-820762-X, pp. 57–60.

- J. Wormald, Court, Kirk, and Community: Scotland, 1470–1625 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1991), ISBN 0-7486-0276-3, pp. 48–9.

- R. Mitchison, A History of Scotland (London: Routledge, 3rd edn., 2002), ISBN 0-415-27880-5, p. 4.

- W. O. Frazer and A. Tyrrell, Social Identity in Early Medieval Britain (London: Continuum, 2000), ISBN 0-7185-0084-9, p. 238.

- G. W. S. Barrow, Kingship and Unity: Scotland 1000–1306 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1989), ISBN 0-7486-0104-X, p. 14.

- R. Crawford, Scotland's Books: A History of Scottish Literature (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009), ISBN 0-19-538623-X.

- R. A. Houston, Scottish Literacy and the Scottish Identity: Illiteracy and Society in Scotland and Northern England, 1600–1800 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002), ISBN 0-521-89088-8, p. 76.

- G. Lamb, "The Orkney Tongue" in D. Omand, ed., The Orkney Book (Edinburgh: Birlinn, 2003), p. 250.

- A. Jennings and A. Kruse, "One Coast-Three Peoples: Names and Ethnicity in the Scottish West during the Early Viking period", in A. Woolf, ed., Scandinavian Scotland – Twenty Years After (St Andrews: St Andrews University Press, 2007), ISBN 0-9512573-7-4, p. 97.

- K. J. Stringer, "Reform Monasticism and Celtic Scotland", in E. J. Cowan and R. A. McDonald, eds, Alba: Celtic Scotland in the Middle Ages (East Lothian: Tuckwell Press, 2000), ISBN 1-86232-151-5, p. 133.

- K. M. Brown, Noble Society in Scotland: Wealth, Family and Culture from the Reformation to the Revolutions (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2004), ISBN 0-7486-1299-8, p. 220.

- J. Wormald, Court, Kirk, and Community: Scotland, 1470–1625 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1991), ISBN 0-7486-0276-3, pp. 60–7.

- A. Macquarrie, Medieval Scotland: Kinship and Nation (Thrupp: Sutton, 2004), ISBN 0-7509-2977-4, p. 128.

- P. J. Bawcutt and J. H. Williams, A Companion to Medieval Scottish Poetry (Woodbridge: Brewer, 2006), ISBN 1-84384-096-0, pp. 29–30.

- M. Lynch, Scotland: A New History (Random House, 2011), ISBN 1-4464-7563-8, pp. 104–7.

- J. Wormald, Court, Kirk, and Community: Scotland, 1470–1625 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1991), ISBN 0-7486-0276-3, pp. 68–72.

- B. Webster, Medieval Scotland: the Making of an Identity (St. Martin's Press, 1997), ISBN 0-333-56761-7, pp. 124–5.

- B. Webster, Medieval Scotland: the Making of an Identity (St. Martin's Press, 1997), ISBN 0-333-56761-7, pp. 119.

- R. T. Lambdin and L. C. Lambdin, Encyclopedia of Medieval Literature (London: Greenwood, 2000), ISBN 0-313-30054-2, p. 508.

- J. T. Koch, Celtic Culture: a Historical Encyclopedia (ABC-CLIO, 2006), ISBN 1-85109-440-7, p. 999.

- I. Brown, T. Owen Clancy, M. Pittock, S. Manning, eds, The Edinburgh History of Scottish Literature: From Columba to the Union, until 1707 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2007), ISBN 0-7486-1615-2, p. 94.

- E. M. Treharne, Old and Middle English c.890-c.1400: an Anthology (Wiley-Blackwell, 2004), ISBN 1-4051-1313-8, p. 108.

- D. Broun, "Gaelic Literacy in Eastern Scotland between 1124 and 1249" in H. Pryce ed., Literacy in Medieval Celtic Societies (Cambridge, 1998), ISBN 0-521-57039-5, pp. 183–201.

- T. O. Clancy, "Scotland, the 'Nennian' recension of the Historia Brittonum, and the Lebor Bretnach", in S. Taylor, ed., Kings, Clerics and Chronicles in Scotland, 500–1297 (Dublin/Portland, 2000), ISBN 1-85182-516-9, pp. 87–107.

- M. Fry, Edinburgh (London: Pan Macmillan, 2011), ISBN 0-330-53997-3.

- A. A. M. Duncan, ed., The Brus (Canongate, 1997), ISBN 0-86241-681-7, p. 3.

- A. Grant, Independence and Nationhood, Scotland 1306–1469 (Baltimore: Edward Arnold, 1984), pp. 102–3.

- Thomas Thomson, ed., Auchinleck Chronicle (Edinburgh, 1819).

- J. Martin, Kingship and Love in Scottish poetry, 1424–1540 (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2008), ISBN 0-7546-6273-X, p. 111.

- J. Graham-Campbell and C. E. Batey, Vikings in Scotland: an Archaeological Survey (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1998), ISBN 0-7486-0641-6, pp. 7–8.

- L. R. Laing, Later Celtic Art in Britain and Ireland (London: Osprey Publishing, 1987), ISBN 0-85263-874-4, p. 37.

- A. Lane, "Citadel of the first Scots", British Archaeology, 62, December 2001. Retrieved 2 December 2010.

- H. Honour and J. Fleming, A World History of Art (London: Macmillan), ISBN 0-333-37185-2, pp. 244–7.

- G. Henderson, Early Medieval Art (London: Penguin, 1972), pp. 63–71.