History of Svalbard

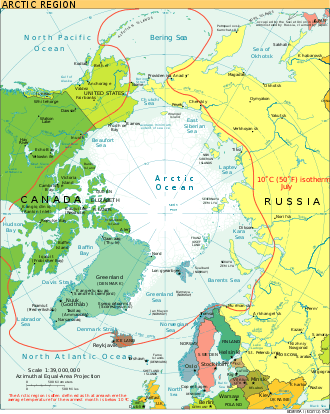

The polar archipelago of Svalbard was first discovered by Willem Barentsz in 1596, although there is disputed evidence of use by Pomors or Norsemen. Whaling for bowhead whales started in 1611, dominated by English and Dutch companies, though other countries participated. At that time there was no agreement about sovereignty. Whaling stations, the largest being Smeerenburg, were built during the 17th century, but gradually whaling decreased. Hunting was carried out from the 17th century by Pomors, but from the 19th century it became more dominated by Norwegians.

Exploration was initially conducted to find new whaling grounds, but from the 18th century some scientific expeditions took place. These were initially large scale, but from the late 19th century they became smaller and increasingly focused on the interior. The most important scientific explorers were Baltazar Mathias Keilhau, Adolf Erik Nordenskiöld and Martin Conway. Sustainable mining started in 1906 with the establishment of Longyearbyen and by the 1920s, permanent coal mining settlements had been established at Barentsburg, Grumant, Pyramiden, Svea and Ny-Ålesund. The Svalbard Treaty came into effect in 1925, granting Norway sovereignty of the archipelago, but prohibiting "warlike activities" and establishing all signatories the right to mine. This both eliminated the mare liberum status of the islands, and also saw a name change from the Spitsbergen Archipelago to Svalbard. By the 1930s, all settlements were either Norwegian or Soviet.

During the Second World War, the settlements were first evacuated and then bombed by the Kriegsmarine, but rebuilt after the war. During the Cold War there were increased tensions between Norway and the Soviet Union, particularly regarding the building of an airport. There was limited oil drilling, and by 1973 more than half the archipelago was protected. Starting in the 1970s, Longyearbyen underwent a process of "normalization" to become a regular community. Arktikugol closed Grumant in 1962 and Pyramiden in 1998, while King Bay had to close mining at Ny-Ålesund after the Kings Bay Affair. The 1990s and 2000s have seen major reductions of the Russian population and the creation of scientific establishments in Ny-Ålesund and Longyearbyen. Tourism has also increased and become a major component of the economy of Longyearbyen.

Svalbard during the Golden Age of Dutch exploration and discovery (c. 1590s–1720s)

First verified discovery of Svalbard as a terra nullius

There is no conclusive evidence of the first human activity on Svalbard. Swedish archeologist Hans Christiansson found flint and slate objects he identified as Stone Age tools dating from ca. 3000 BC,[1] but there is little support among his peers as no dwelling place has been found.[2][3] During the 19th century, Norwegian historians proposed that Norse seamen had found Svalbard in 1194. This is based on annals that found Svalbarði four days sailing from Iceland. Although it forms the basis for the modern name of the archipelago, there is no scientific consensus that supports the hypothesis. Russian historians have proposed that Russian Pomors may have visited the island as early as the 15th century.[4] This line was largely pursued by Soviet scholars, but again, no conclusive evidence has been found.[5] The Portuguese may also lay claim to have discovered or known about Svalbard first due to the close resemblance of the archipelago in the Cantino Planisphere, an early map famous for documenting Portuguese discoveries in the New World. If proven this would predate the official discovery by 94 years.

The first undisputed discovery of the archipelago was an expedition led by the Dutch mariner Willem Barentsz, who was looking for the Northeast passage to China.[6] He first spotted Bjørnøya on 10 June 1596[7] and the northwestern tip of Spitsbergen on 17 June.[6] The sighting of the archipelago was included in the accounts and maps made by the expedition and Spitsbergen was quickly included by cartographers.[8] Henry Hudson explored the islands in 1607.

International whaling base

.jpg)

The first hunting expedition, to Bjørnøya, was organized by the Muscovy Company led by Steven Bennet in 1604. Although they found thousands of walrus, they were only able to kill a few because of their lack of experience. The following year he was more successful and returned annually until they in a few years had achieved local extinction. After Jonas Poole reported seeing a "great store of whales" off Spitsbergen in 1610, the Muscovy Company sent a whaling expedition to the island under command of Poole and Thomas Edge in 1611. They hired Basque experts to hunt the bowhead whale, but both ships were wrecked and the crews rescued by English interlope. The following year, the Muscovy Company sent a new expedition, but was met by both Dutch and Spanish whalers. The company claimed exclusive rights to the area and sent away the contenders. In 1613, seven armed English ships were sent on the expedition which expelled a few dozen Dutch, Spanish and French vessels.[9]

This led to an international political conflict. The Dutch rejected the English exclusive rights, claiming the mare liberum principle. Christian IV claimed that Denmark–Norway had the rights to all of Northern Sea in view of Greenland being an old Norwegian tax-land. England offered to purchase the rights from Denmark–Norway in 1614, but the offer was turned down, after which the English reverted to their exclusive rights claim. In 1615, Denmark–Norway sent three man-o-wars to collect taxes from English and Dutch whalers, but all refused to pay.[10] The issue ended in a political deadlock, with Denmark–Norway and England both claiming sovereignty and France, the Netherlands and Spain claiming it a free zone under mare liberum.[11]

_5.jpg)

In 1614, the English and Dutch partitioned the island, as the aggression was hampering the profitability of both groups. That year, the Netherlands created Noordsche Compagnie as a whaling cartel. After the Muscovy Company fell into financial difficulties some years later, the Noordsche Compagnie got the upper hand and was able to dominate the whaling and fend off the English.[11] They established themselves in the northwestern corner of Spitsbergen (around Albert I Land) and only permitted a limited Danish presence. The English whaled further south, while the French were allocated to the north coast and the open sea. From the 1630s, the situation stabilized and there were only a limited number of aggressive incidents.[12]

Initially, all nations hired Basque whalers,[13] although they gradually disappeared after their knowledge was learned by their companions. The whaling method was based on landing the whale, where it would be partitioned and the blubber boiled. With a high concentration of whales close to land, the method was efficient, as the companies would split the crew between the land station and hunting.[14] The most famous land station was the Dutch Smeerenburg on Amsterdam Island which had up to 200 people employed. Because of the high costs involved, only larger companies conducted whaling. By the late 17th century there were between 200 and 300 ships and in excess of 10,000 whalers around Spitsbergen.[15] The first overwintering was accidentally experienced by an English group in Bellsund in 1630–31. The first planned overwintering was achieved by the Noordsche Compagnie in 1633–34.[16]

A limited amount of open-sea whaling was performed by interlopers—independent entrepreneurs. The Noordsche Compagnie was disbanded by the government in 1642. The decade also saw an increase in whaling outside the main bays and fjords.[17] This gradually resulted in the abandoning of land stations as technological innovation allowed flensing along the ship, which allowed for pelagic whaling. Cooking of the oil was moved to the mainland.[18] While more cost-efficient, it resulted in a large portion of the meat being wasted. During the 18th century, Dutch whaling was reduced, until it ceased after 1770. The British gradually took the lead in Arctic whaling, but by around the start of the 19th century bowhead whales were scarce around Spitsbergen and the whalers moved elsewhere.[19]

Hunting

It is not known when Pomors first came to Svalbard, although permanent activity had been established by the mid-16th century.[20] Hunters were sent by merchants, and monasteries, such as Solovetsky Monastery, and settled in smaller stations along the coast. They would hunt reindeer, Arctic fox, seals, walrus and polar bears. The activity was most extensive at the end of the 18th century, when an estimated 100 to 150 overwintered.[21] Unlike the whaling, Pomor activity was sustainable, they alternated stations between seasons and did not deplete the natural resources.[22]

Seal hunting in the waters between Svalbard and Greenland was started by Germans in the late 17th century. The activity was later taken over by Norwegians and Danish in the 18th century. Sealing was less profitable but could be carried with much less capital.[23] Norwegians came in contact with the Russians through the Pomor trade. Despite earlier attempts, not until 1794 did a Norwegian party reach Bjørnøya and the following years Spitsbergen. The first Norwegian citizens to reach Spitsbergen proper were a number of Coast Sámi from the Hammerfest region, who were hired as part of a Russian crew for an expedition in 1795.[24] From the 1820s the Norwegian hunting expeditions were taken up and continued through the rest of the century. Tromsø gradually replaced Hammerfest as the main port of origin. In the last third of the century, an average 27 Norwegian ships sailed to Svalbard.[25] In the winter of 1872–73, seventeen seal hunters died in the Svenskehuset Tragedy.[26]

Further exploration

Exploration of the archipelago started in the 1610s as the whaling companies would send out small ships to find new areas to exploit. By 1650 it was established that Spitsbergen was an island and not connected to Greenland. Whalers gradually accumulated a good geographic knowledge of the coastline, but the interior remained uncharted.[27] The first scientific expedition to Svalbard was the Russian Čičagov Expedition between 1764 and 1766, which passed Svalbard in an unsuccessful attempt to find the Northern Sea Route. It made among water and topography measurements.[28] The second expedition was organized by the Royal Navy and led by Constantine Phipps in 1773. His two ships, the Racehorse and the Carcass got stuck in the ice around Sjuøyane before returning. They collected zoological and botanical samples and measured water temperatures, among others.[29]

Scientific exploration increased through the 18th century, with the most extensive surveys being carried out by William Scoresby, who published several papers on the Arctic, and Baltazar Mathias Keilhau.[29] The latter was the first to carry out expeditions in the interior, abandoning the large-scale operations used by the British and Russians. With the exception of the British, smaller more targeted expeditions became the norm. Science also took foot as the dominant motivation for expeditions until the end of the 19th century.[30] A notable exception was the French Recherche expedition of 1838–39, which resulted in numerous publications in multiple fields and the construction of an observatory. Swedish exploration started with Sven Lovén in 1837, with lead way to Sweden dominating scientific investigations in the last half of the century. Particularly Otto Torell and Adolf Erik Nordenskiöld dedicated much of their research to the archipelago.[31] Martin Conway was the first to produce a map of the interior of Spitsbergen.[32]

Svalbard was used as the starting point for several expeditions to reach the North Pole by air. S. A. Andrée's Arctic Balloon Expedition failed in 1897.[33] Ny-Ålesund was the basis for four attempts between 1925 and 1928, including Roald Amundsen's first attempt with a flying boat; Floyd Bennett and Richard E. Byrd claimed they succeeded in 1926, but this has since been rejected.[34] Amundsen's airship Norge is now credited as the first to the pole. Umberto Nobile's airship Italia crashed in 1928, resulting in the largest search in polar history.[34]

Industrialization

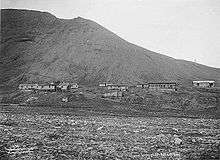

The first attempt at creating a permanent settlement was carried out by Sweden's Alfred Gabriel Nathorst. He established Kapp Thordsen on Isfjorden in 1872, but the planned phosphorite mining was not carried out and the settlement abandoned.[35] Coal had always been mined and gathered by whalers and hunters, but industrial mining did not start until 1899. Søren Zachariassen of Tromsø was the first to establish a mining company to exploit Svalbard minerals. He claimed several places in Isfjorden and exported coal to the mainland, but lack of capital stopped further growth.[36]

The first commercially viable mining company was John Munroe Longyear's Arctic Coal Company, which established Longyear City (from 1925 Longyearbyen). By 1910, 200 men were working for the company.[36] The town and mines were bought by the Norwegian-owned Store Norske Spitsbergen Kulkompani in 1916.[37] Another early entrepreneur was Ernest Mansfield and his Northern Exploration Company. He started marble mining on Blomstrandhalvøya, but the marble was unusable and his company never had any profitable ventures, despite surveying large parts of the island.[35] By the 1910s, it was established that coal was the only economically viable mining activity on Svalbard. Swedish interests established mines at Pyramiden and Sveagruva,[38] while Dutch investors established Barentsburg in 1920.[39] During the First World War, Norway saw the advantage of increasing self-supply of coal and Kings Bay established mining in Ny-Ålesund in 1916.[38]

Jurisdiction

Although Denmark–Norway never formally gave up its claim to Svalbard, the archipelago continued to be a terra nullius—a land without a government. The work to establish an administration was initiated by Nordenskiöld in 1871, in which he established that only Russia and Norway would object to an annexation of the island.[40] Fridtjof Nansen's endeavors raised the Norwegian public's consciousness of the Arctic, which again brought forth public support for annexation of Svalbard.[41] Yet the need for jurisdiction came from the mining community. Firstly, there was no means to make a mining claim legal. Secondly, there was a need for conflict resolution, particularly regarding labor conflicts, which often saw the mining company and the workers have different nationalities.[42]

The Government of Norway took initiative in 1907 for negotiations between the involved states. Multilateral conferences were held in 1910, 1912 and 1914, all of which proposed various types of joint rule.[43] The break-through came at the Paris Peace Conference. Germany and Russia had both been excluded, while Norway enjoyed much goodwill after their neutral ally policy during the war and was at the same time seen as harmless. The Svalbard Treaty of 9 February 1920 granted Norway full sovereignty over Svalbard, although with two major limitations: all parties to the treaty had equal rights to economic resources and the archipelago was not to be used for "warlike purposes".[44]

After significant political debate, a proposal to establish Svalbard as a dependency and administrate it from Tromsø was rejected. Instead the Svalbard Act specified that the islands would be administrated by the Governor of Svalbard and was considered "part of the Kingdom of Norway", although not regarded as a county. The islands had until then been known as the Spitsbergen Archipelago, and it was at this time the term Svalbard was introduced. The legislation took effect on 14 August 1925.[45] A mining code was passed in 1925 and by 1927 all mining claims, some of which conflicted, were resolved.[46] All unclaimed land was taken over by the Norwegian Government.[47] Although the Soviet Union was initially skeptical to the treaty, they were willing to trade a signing of it in exchange for a Norwegian recognition of the Soviet regime.[48]

During the 1920s, mining fell into an economic slump, with several of the mining communities being closed. By the 1930s, only Store Norske and the Soviet state-owned Arktikugol were left. This led to more large-scale production, but left the archipelago with only two geopolitical interests, which led to a bilateralization of politics. Because both the Governor and the Commissioner of Mining only had a single person, which was stationed on the mainland during the winter, there was little Norwegian control over the Soviet communities.[49] Pre-war coal production peaked at 786,000 tonnes (774,000 long tons; 866,000 short tons) in 1936, 57 percent of which was from Norwegian mines, and at which time the archipelago had a population of 1,900. The 1930s also saw a limited cod fishery from Ny-Ålesund and a limited tourism with a scheduled ship service to the mainland.[50]

World War II

Svalbard was initially unaffected by the occupation of Norway by Nazi Germany on 9 April 1940. However, following the German attack on the Soviet Union, Svalbard became of strategic importance to secure supplies between the Allies. At first, the Soviet Union proposed Soviet–British occupation of the archipelago, but this was rejected by the Norwegian government-in-exile. Instead, an evacuation of all Norwegian and Soviet settlements were carried out by Operation Gauntlet in August and September.[51]

With the island evacuated, German troops occupied Longyearbyen, where they built an airstrip and a weather station. In May 1942, a Norwegian expedition was sent to liberate the island; they were attacked by German aircraft, but were able to set up a garrison in Barentsburg. The German outpost was subsequently abandoned. The Germans, presumably underestimating the Allied forces' size, initiated Operation Zitronella. Along with nine destroyers, the battleships Tirpitz, the Scharnhorst were sent to Isfjorden where they leveled Barentsburg, Grumant and Longyearbyen. Sveagruva was bombed in an air raid in 1944.[52] The Germans established a weather station on Hopen, which was taken over by Norway after the war.[53]

Cold War

In 1944, the Soviet Union proposed that Svalbard become a condominium under joint Norwegian and Soviet rule, except for Bjørnøya, which would be transferred to the Soviet Union.[54] Although the proposal was discussed in Norway, it was ultimately rejected in 1947.[55] Reconstruction of the Norwegian settlements started in 1945 and they were quickly operational, and reaching pre-war production levels within a few years. Soviet reconstruction started in 1946, but Arktikugol was slower at gaining momentum in production. The Norwegian population stabilized at about 1,000 people, while there were about twice as many Soviets. The two nations built infrastructure, such as a postal service, radio stations and transport, independent of each other.[56]

The political tension between Norway and the Soviet Union became heated after Norway joined NATO in 1949. The Soviet Union issued memorandums to Norway stating that Svalbard could not be under a NATO joint command, but this was rejected by Norway, and the issue laid at rest.[56] A new protest was issued in 1958 after Norsk Polar Navigasjon proposed building a private airport at Ny-Ålesund, which was then actively opposed by the Norwegian Government to avoid agitating the Soviet Union.[57] New protests were issued against the establishment of the European Space Research Organization's Kongsfjord Telemetry Station, although the protests did not stop construction. A compromise about a Norwegian civilian airport was reached in 1971[58] and Svalbard Airport, Longyear opened in 1975, serving both Soviet and Norwegian towns.[59]

Grumant was closed in 1961.[60] The following year, 21 miners were killed in an accident in Ny-Ålesund, which led to the Kings Bay Affair, ultimately resulting in the withdrawal of Gerhardsen's Third Cabinet. Oil drilling was started by Caltex in 1961. They were granted claims based on indications, rather than samples, of oil, which was not granted to Arktikugol, leading to strained relations with the Soviet Union.[59] No commercially viable wells were found. A new round of searching in the 1980s was also fruitless.[61]

Both the Kings Bay Affair and the Caltex Affair initiated public debate about the administration of Svalbard, and in particular the lack of resources and control of Soviet settlements. Funding for local and central administration was increased heavily[59] and the Governor increased its activities in Soviet settlements.[60] After mining was closed in Ny-Ålesund, the Norwegian Polar Institute took a dominant role in converting it to an international research station.[62] In 1973, more than half the archipelago was protected through four national parks, fourteen bird sanctuaries and four nature reserves.[60] Store Norske was nationalized between 1973 and 1976.[63] From 1973, they started mining at Svea, but operations ceased in 1987.[64]

Normalization

"Normalization" was a term coined in the 1970s to transform Longyearbyen from a company town to a regular community.[65] The first steps towards local democracy were taken with the 1971 establishment of the Svalbard Council for the Norwegian population, although it only had a commentary function.[66] Public services were transferred to the company Svalbard Samfunnsdrift in 1989,[67] while private enterprise established services such as construction companies and a mall.[68] Tourism became a livelihood with the establishment of hotels from 1995.[69] From 2002 Longyearbyen Community Council was incorporated with many of the same responsibilities as a municipality.[70]

Since the 1990s, several research and hi-tech institutes have established themselves, such as the University Centre in Svalbard, the European Incoherent Scatter Scientific Association,[71] the Svalbard Satellite Station,[64] the Svalbard Undersea Cable System[72] and the Svalbard Global Seed Vault.[73] The 1990s saw a large reduction in Russian activity. Schools were closed in 1994 and children and mothers were sent to the mainland, reducing the population of Barentsburg to 800 and of Pyramiden to 600.[74] Operations resumed at Svea in 1997,[64] while Pyramiden was abandoned in 1998.[75] The Svalbard Environmental Protection Act came into effect in 2002[76] and was followed up with three new national parks and three new nature reserves.[77] From 1990 to 2011, the Russian and Ukrainian population fell from 2,300 to 370, while the Norwegian population increased from 1,100 to 2,000.[78]

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to History of Svalbard. |

- Bibliography

- Arlov, Thor B. (1994). A short history of Svalbard. Oslo: Norwegian Polar Institute. ISBN 82-90307-55-1.

- Hisdal, Vidar (1998). Svalbard: nature and history. Oslo: Norwegian Polar Institute. ISBN 82-7666-152-1.

- Holm, Kari (1999). Longyearbyen – Svalbard: historisk veiviser (in Norwegian). ISBN 82-992142-4-6.

- Carlheim-Gyllensköld, V. (1900). På åttionda breddgraden. En bok om den svensk-ryska gradmätningen på Spetsbergen; den förberedande expeitionen sommaren 1898, dess färd rundt spetsbergens kuster, äfventyr i båtar och på isen; ryssars och skandinavers forna färder; m.m., m.m. Stockholm: Albert Bonniers förlag.

- Notes

- Christiansson, Hans; Povl Simonsen (1970). Stone Age Finds from Spitsbergen. Acta Borealia, v. 11. Universitetsforlaget. Retrieved 18 Dec 2012.

- Arlov (1994): 12

- Bjerck, Hein B (2000). "Stone Age settlement on Svalbard? A re-evaluation of previous finds and the results of a recent field survey". Polar Record. 36: 97–112. doi:10.1017/S003224740001620X.

- Arlov (1994): 13

- Arlov (1994): 14

- Arlov (1994): 9

- Arlov (1994): 10

- Arlov (1994): 11

- Arlov (1994): 16

- Arlov (1994): 18

- Arlov (1994): 19

- Arlov (1994): 20

- Arlov (1994): 23

- Arlov (1994): 24

- Arlov (1994): 25

- Arlov (1994):35

- Arlov (1994): 27

- Arlov (1994): 31

- Arlov (1994): 32

- Arlov (1994): 36

- Arlov (1994): 37

- Arlov (1994): 38

- Arlov (1994): 34

- Carlheim-Gyllensköld (1900), p. 155

- Arlov (1994): 39

- Goll, Sven (19 September 2008). "Arctic mystery resolved after 135 years". Aftenposten. Archived from the original on 29 June 2011. Retrieved 29 June 2011.

- Arlov (1994): 42

- Arlov (1994): 43

- Arlov (1994): 44

- Arlov (1994): 45

- Arlov (1994): 46

- Ørvoll, Oddveig Øien. "The history of place names in the Arctic". Norwegian Polar Institute. Archived from the original on 29 April 2012. Retrieved 19 April 2012.

- Arlov (1994): 48

- Hisdal (1998): 103

- Arlov (1994): 51

- Arlov (1994): 52

- Arlov (1994): 57

- Arlov (1994): 56

- Arlov (1994): 69

- Arlov (1994): 60

- Arlov (1994): 62

- Arlov (1994): 63

- Arlov (1994): 64

- Arlov (1994): 65

- Arlov (1994): 68

- Arlov (1994): 70

- "Industrial, mining and commercial activities". Report No. 9 to the Storting (1999-2000): Svalbard. Norwegian Ministry of Justice and the Police. 29 October 1999. Archived from the original on 11 October 2012. Retrieved 19 April 2012.

- Arlov (1994): 71

- Arlov (1994): 72

- Arlov (1994): 73

- Arlov (1994): 74

- Arlov (1994): 75

- Holm (1999): 53

- Arlov (1994): 76

- Arlov (1994): 78

- Arlov (1994): 79

- Arlov (1994): 80

- Arlov (1994): 81

- Arlov (1994): 82

- Arlov (1994): 83

- Arlov (1994): 84

- Arlov (1994): 85

- Holm (1999): 119

- Holm (1999): 141

- Arlov (1994): 86

- Hisdal (1998): 116

- Holm (1999): 137

- Holm (1999): 125

- Holm (1999): 132

- "Næringsvirksomhet". St.meld. nr. 22 (2008-2009): Svalbard. Ministry of Justice and the Police. 17 April 2009. Retrieved 24 March 2010.

- Holm (1999): 36

- Gjesteland, Eirik (2003). "Technical solution and implementation of the Svalbard fibre cable" (PDF). Teletronikk (3): 140–152. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 April 2012. Retrieved 12 April 2012.

- "Svalbard Global Seed Vault: Frequently Asked Questions". Government.no. Archived from the original on 25 February 2012. Retrieved 11 April 2012.

- Hisdal (1998): 115

- "Settlements". Governor of Svalbard. Archived from the original on 6 May 2012. Retrieved 19 April 2012.

- "Environmental Act". Governor of Svalbard. Archived from the original on 29 April 2012. Retrieved 19 April 2012.

- "Protected Areas in Svalbard". Norwegian Directorate for Nature Management. Archived from the original on 29 February 2012. Retrieved 4 March 2012.

- "Personer i bosetningene 1. januar. Svalbard" (in Norwegian). Statistics Norway. Archived from the original on 12 October 2009. Retrieved 19 April 2012.