Kingdom of Strathclyde

Strathclyde (lit. "Strath of the River Clyde"), originally Cumbric: Ystrad Clud or Alclud (and Strath-Clota in Anglo-Saxon), was one of the early medieval kingdoms of the Britons in what the Welsh call Hen Ogledd ("the Old North"), the Brythonic-speaking parts of what is now southern Scotland and northern England. The kingdom developed during the post-Roman period. It is also known as Alt Clut, a Brittonic term for Dumbarton Castle,[1] the medieval capital of the region. It may have had its origins with the Brythonic Damnonii people of Ptolemy's Geography.

Kingdom of Strathclyde Teyrnas Ystrad Clut | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5th century–c. 1030 | |||||||||

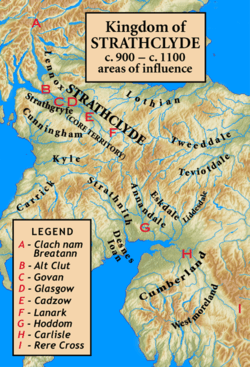

The core of Strathclyde is the strath of the River Clyde. The major sites associated with the kingdom are shown, as is the marker Clach nam Breatann (English: Rock of the Britons), the probable northern extent of the kingdom at an early time. Other areas were added to or subtracted from the kingdom at different times. | |||||||||

| Capital | Dumbarton and Govan | ||||||||

| Common languages | Cumbric | ||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||

| Historical era | Middle Ages | ||||||||

• Established | 5th century | ||||||||

• Incorporated into the Kingdom of Scotland | c. 1030 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | ∟ Dumfries and Galloway ∟ East Ayrshire ∟ North Ayrshire ∟ South Ayrshire ∟ South Lanarkshire ∟ North Lanarkshire ∟ East Renfrewshire ∟ Renfrewshire ∟ City of Glasgow ∟ Inverclyde ∟ East Dunbartonshire ∟ West Dunbartonshire ∟ Argyll and Bute ∟ Stirling | ||||||||

The language of Strathclyde, and that of the Britons in surrounding areas under non-native rulership, is known as Cumbric, a dialect or language closely related to Old Welsh, and in modern terms to Welsh, Cornish and Breton. Scottish toponymy and archaeology points to some later settlement by Vikings or Norse–Gaels (see Scandinavian Scotland), although to a lesser degree than in neighbouring Galloway. A small number of Anglian place-names show some limited settlement by Anglo-Saxon incomers from Northumbria prior to the Norse settlement. Owing to the series of language changes in the area, it is not possible to say whether any Goidelic settlement took place before Gaelic was introduced in the High Middle Ages during the 11th century.

After the sack of Dumbarton Rock by a Viking army from Dublin in 870, the name Strathclyde came into use, perhaps reflecting a move of the centre of the kingdom to Govan. In the same period, it was also referred to as Cumbria, and its inhabitants as Cumbrians. During the High Middle Ages, the area was conquered by the Goidelic-speaking Kingdom of Alba in the 11th century, becoming part of the new Kingdom of Scotland. However, it remained a distinctive Brythonic area into the 12th and 13th centuries.

Origins

Ptolemy's Geographia – a sailors' chart, not an ethnographical survey[2] – lists a number of tribes, or groups of tribes, in southern Scotland at around the time of the Roman invasion and the establishment of Roman Britain in the 1st century AD. As well as the Damnonii, Ptolemy lists the Otalini, whose capital appears to have been Traprain Law; to their west, the Selgovae in the Southern Uplands and, further west in Galloway, the Novantae. In addition, a group known as the Maeatae, probably in the area around Stirling, appear in later Roman records. The capital of the Damnonii is believed to have been at Carman, near Dumbarton, but around five miles inland from the River Clyde.

Although the northern frontier appears to have been Hadrian's Wall for most of the history of Roman Britain, the extent of Roman influence north of the Wall is obscure. Certainly, Roman forts existed north of the wall, and forts as far north as Cramond may have been in long-term occupation. Moreover, the formal frontier was three times moved further north. Twice it was advanced to the line of the Antonine Wall, at about the time when Hadrian's Wall was built and again under Septimius Severus, and once further north, beyond the river Tay, during Agricola's campaigns, although, each time, it was soon withdrawn. In addition to these contacts, Roman armies undertook punitive expeditions north of the frontiers. Northern natives also travelled south of the wall, to trade, to raid and to serve in the Roman army. Roman traders may have travelled north, and Roman subsidies, or bribes, were sent to useful tribes and leaders. The extent to which Roman Britain was romanised is debated, and if there are doubts about the areas under close Roman control, then there must be even more doubts over the degree to which the Damnonii were romanised.[3]

The final period of Roman Britain saw an apparent increase in attacks by land and sea, the raiders including the Picts, Scotti and the mysterious Attacotti whose origins are not certain.[4] These raids will have also targeted the tribes of southern Scotland. The supposed final withdrawal of Roman forces around 410 is unlikely to have been of military impact on the Damnonii, although the withdrawal of pay from the residual Wall garrison will have had a very considerable economic effect.

No historical source gives any firm information on the boundaries of the Kingdom of Strathclyde, but suggestions have been offered on the basis of place-names and topography. Near the north end of Loch Lomond, which can be reached by boat from the Clyde, lies Clach nam Breatann, the Rock of the Britains, which is thought to have gained its name as a marker at the northern limit of Alt Clut. The Campsie Fells and the marshes between Loch Lomond and Stirling may have represented another boundary. To the south, the kingdom extended some distance up the strath of the Clyde, and along the coast probably extended south towards Ayr.[5]

Early historic period

The Old North

Although often referred to as the Dark Ages, the period after the end of Roman rule in southern Scotland, while poorly understood, is considerably less dark than the Roman period. Archaeologists and historians have offered varying accounts of the period over the last century and a half. The written sources available for the period are largely Irish and Welsh, and very few indeed are contemporary with the period between 400 and 600.

Irish sources report events in the kingdom of Dumbarton only when they have an Irish link. Excepting the 6th-century jeremiad by Gildas and the poetry attributed to Taliesin and Aneirin—in particular y Gododdin, thought to have been composed in Scotland in the 6th century—Welsh sources generally date from a much later period. Some are informed by the political attitudes prevalent in Wales in the 9th century and after. Bede, whose prejudice is apparent, rarely mentions Britons, and then usually in uncomplimentary terms.

Two kings are known from near contemporary sources in this early period. The first is Coroticus or Ceretic Guletic (Welsh: Ceredig), known as the recipient of a letter from Saint Patrick, and stated by a 7th-century biographer to have been king of the Height of the Clyde, Dumbarton Rock, placing him in the second half of the 5th century. From Patrick's letter it is clear that Ceretic was a Christian, and it is likely that the ruling class of the area were also Christians, at least in name. His descendant Rhydderch Hael is named in Adomnán's Life of Saint Columba. Rhydderch was a contemporary of Áedán mac Gabráin of Dál Riata and Urien of Rheged, to whom he is linked by various traditions and tales, and also of Æthelfrith of Bernicia.

The Christianisation of southern Scotland, if Patrick's letter to Coroticus was indeed to a king in Strathclyde, had therefore made considerable progress when the first historical sources appear. Further south, at Whithorn, a Christian inscription is known from the second half of the 5th century, perhaps commemorating a new church. How this came about is unknown. Unlike Columba, Kentigern (Welsh: Cyndeyrn Garthwys), the supposed apostle to the Britons of the Clyde, is a shadowy figure and Jocelyn of Furness's 12th century Life is late and of doubtful authenticity though Jackson[6] believed that Jocelyn's version might have been based on an earlier Cumbric-language original.

The Kingdom of Alt Clut

.png)

After 600, information on the Britons of Alt Clut becomes slightly more common in the sources. However, historians have disagreed as to how these should be interpreted. Broadly speaking, they have tended to produce theories which place their subject at the centre of the history of north Britain in the Early Historic period. The result is a series of narratives which cannot be reconciled.[7] More recent historiography may have gone some way to addressing this problem.

At the beginning of the 7th century, Áedán mac Gabráin may have been the most powerful king in northern Britain, and Dál Riata was at its height. Áedán's byname in later Welsh poetry, Aeddan Fradawg (Áedán the Treacherous) does not speak to a favourable reputation among the Britons of Alt Clut, and it may be that he seized control of Alt Clut. Áedán's dominance came to an end around 604, when his army, including Irish kings and Bernician exiles, was defeated by Æthelfrith at the battle of Degsastan.

It is supposed, on rather weak evidence, that Æthelfrith, his successor Edwin and Bernician and Northumbrian kings after them expanded into southern Scotland. Such evidence as there is, such as the conquest of Elmet, the wars in north Wales and with Mercia, would argue for a more southerly focus of Northumbrian activity in the first half of the 7th century. The report in the Annals of Ulster for 638, "the battle of Glenn Muiresan and the besieging of Eten" (Eidyn, later Edinburgh), has been taken to represent the capture of Eidyn by the Northumbrian king Oswald, son of Æthelfrith, but the Annals mention neither capture, nor Northumbrians, so this is rather a tenuous identification.[8]

In 642, the Annals of Ulster report that the Britons of Alt Clut led by Eugein son of Beli defeated the men of Dál Riata and killed Domnall Brecc, grandson of Áedán, at Strathcarron, and this victory is also recorded in an addition to Y Gododdin. The site of this battle lies in the area known in later Welsh sources as Bannawg--the name Bannockburn is presumed to be related--which is thought to have meant the very extensive marshes and bogs between Loch Lomond and the river Forth, and the hills and lochs to the north, which separated the lands of the Britons from those of Dál Riata and the Picts, and this land was not worth fighting over. However, the lands to the south and east of this waste were controlled by smaller, nameless British kingdoms. Powerful neighbouring kings, whether in Alt Clut, Dál Riata, Pictland or Bernicia, would have imposed tribute on these petty kings, and wars for the overlordship of this area seem to have been regular events in the 6th to 8th centuries.

There are few definite reports of Alt Clut in the remainder of the 7th century, although it is possible that the Irish annals contain entries which may be related to Alt Clut. In the last quarter of the 7th century, a number of battles in Ireland, largely in areas along the Irish Sea coast, are reported where Britons take part. It is usually assumed that these Britons are mercenaries, or exiles dispossessed by some Anglo-Saxon conquest in northern Britain. However, it may be that these represent campaigns by kings of Alt Clut, whose kingdom was certainly part of the region linked by the Irish Sea. All of Alt Clut's neighbours, Northumbria, Pictland and Dál Riata, are known to have sent armies to Ireland on occasions.[9]

The Annals of Ulster in the early 8th century report two battles between Alt Clut and Dál Riata, at "Lorg Ecclet" (unknown) in 711, and at "the rock called Minuirc" in 717. Whether their appearance in the record has any significance or whether it is just happenstance is unclear. Later in the 8th century, it appears that the Pictish king Óengus made at least three campaigns against Alt Clut, none successful. In 744 the Picts acted alone, and in 750 Óengus may have cooperated with Eadberht of Northumbria in a campaign in which Talorgan, brother of Óengus, was killed in a heavy Pictish defeat at the hands of Teudebur of Alt Clut, perhaps at Mugdock, near Milngavie. Eadberht is said to have taken the plain of Kyle in 750, around modern Ayr, presumably from Alt Clut.

Teudebur died around 752, and it was probably his son Dumnagual who faced a joint effort by Óengus and Eadberht in 756. The Picts and Northumbrians laid siege to Dumbarton Rock, and extracted a submission from Dumnagual. It is doubtful whether the agreement, whatever it may have been, was kept, for Eadberht's army was all but wiped out—whether by their supposed allies or by recent enemies is unclear—on its way back to Northumbria.

After this, little is heard of Alt Clut or its kings until the 9th century. The "burning", the usual term for capture, of Alt Clut is reported in 780, although by whom and in what circumstances is not known. Thereafter Dunblane was burned by the men of Alt Clut in 849, perhaps in the reign of Artgal.

The Viking Age

An army, led by the Viking chiefs known in Irish as Amlaíb Conung and Ímar, laid siege in 870 to Alt Clut, a siege which lasted some four months and led to the destruction of the citadel and the taking of a very large number of captives. The siege and capture are reported by Welsh and Irish sources, and the Annals of Ulster say that in 871, after overwintering on the Clyde:

Amlaíb and Ímar returned to Áth Cliath (Dublin) from Alba with two hundred ships, bringing away with them in captivity to Ireland a great prey of Angles and Britons and Picts.

King Artgal map Dumnagual, called "king of the Britons of Strathclyde", was among the captives, and it is reported that he was killed in Dublin in 872 at the instigation of Causantín mac Cináeda. He was followed by his son Run of Alt Clut, who was married to Causantín's sister. Eochaid, the result of this marriage, may have been king of Strathclyde, or of the kingdom of Alba.

From this time forward, and perhaps from much earlier, the kingdom of Strathclyde was subject to periodic domination by the kings of Alba. However, the earlier idea, that the heirs to the Scots throne ruled Strathclyde, or Cumbria as an appanage, has relatively little support, and the degree of Scots control should not be overstated. This period probably saw a degree of Norse, or Norse-Gael settlement in Strathclyde. A number of place-names, in particular a cluster on the coast facing the Cumbraes, and monuments such as the hogback graves at Govan, are some of the remains of these newcomers.

A Welsh tradition in the Brut y Tywysogion claimed that in 890: "[t]he men of Strathclyde, those that refused to unite with the English, had to depart from their country and go into Gwynedd." This seems confused or misdated as Edward the Elder was not master of his own kingdom of Wessex in 890, let alone a force north of the Humber Estuary, and still less in Strathclyde. Later in Edward's reign, and in that of Athelstan, the kings of Wessex did extend their power far north. Athelstan defeated the men of Strathclyde in 934 and at the battle of Brunanburh in 937.[10]

Following the battle of Brunanburh, Dyfnwal ab Owain became king of Strathclyde, perhaps reigning from c. 937 until 971. It has been supposed that he was installed as king by Máel Coluim mac Domnaill, to whom Edmund of Wessex had "let" the kingdom of Strathclyde, but again, as with earlier ideas of an appanage, this is probably to overstate the case and to follow John of Fordun's version of history more closely than the facts merit. Dyfnwal died, on pilgrimage in Rome, in 975. In this period, the kingdom of Strathclyde may have extended far to the south, perhaps beyond the Solway Firth into modern English Cumbria, although this is far from certain. Local tradition in English Cumbria recounts how Dunmail (presumably Dyfnwal III) the so-called "Last King of Cumbria" was killed at the Battle of Dunmail Raise in 945. A large cairn on what was the boundary between Cumberland and Westmorland – thus, the boundary between the Cumbrians and the English – marks where he is supposed to have fallen. His sons are said to have escaped up the nearby mountain and thrown the Cumbrian crown jewels into Grisedale Tarn before being themselves captured, blinded and castrated by the victorious English.

The end of Strathclyde

If the kings of Alba imagined, as John of Fordun did, that they were rulers of Strathclyde, the death of Cuilén mac Iduilb and his brother Eochaid at the hands of Rhydderch ap Dyfnwal in 971, said to be in revenge for the rape or abduction of his daughter, shows otherwise. A major source for confusion comes from the name of Rhydderch's successor, Máel Coluim, now thought to be a son of the Dyfnwal ab Owain who died in Rome, but long confused with the later king of Scots Máel Coluim mac Cináeda.[11] Máel Coluim appears to have been followed by Owen the Bald who is thought to have died at the battle of Carham in 1018. It seems likely that Owen had a successor, although his name is unknown.

Some time after 1018 and before 1054, the kingdom of Strathclyde appears to have been conquered by the Scots, most probably during the reign of Máel Coluim mac Cináeda who died in 1034.[12] In 1054, the English king Edward the Confessor dispatched Earl Siward of Northumbria against the Scots, ruled by Mac Bethad mac Findláich (Macbeth), along with an otherwise unknown "Malcolm son of the king of the Cumbrians", in Strathclyde. The name Malcolm or Máel Coluim again caused confusion, some historians later supposing that this was the later king of Scots Máel Coluim mac Donnchada (Máel Coluim Cenn Mór). It is not known if Malcolm/Máel Coluim ever became "king of the Cumbrians", or, if so, for how long.[13]

The Keswick area was conquered by the Anglo-Saxon Kingdom of Northumbria in the seventh century, but Northumbria was destroyed by the Vikings in the late ninth. In the early tenth century it became part of Strathclyde; it remained part of Strathclyde until about 1050, when Siward, Earl of Northumbria, conquered that part of Cumbria.[14]

Carlisle was part of Scotland by 1066, and thus was not recorded in the 1086 Domesday Book. This changed in 1092, when William the Conqueror's son William Rufus invaded the region and incorporated Cumberland into England. The construction of Carlisle Castle began in 1093 on the site of the Roman fort, south of the River Eden. The castle was rebuilt in stone in 1112, with a keep and the city walls.

By the 1070s, if not earlier in the reign of Máel Coluim mac Donnchada, it appears that the Scots again controlled Strathclyde. It is certain that Strathclyde did indeed become an appanage, for it was granted by Alexander I to his brother David, Prince of the Cumbrians, later David I, in 1107.

See also

- List of Kings of Strathclyde

- King of the Britons

Notes

- Clarkson, Strathclyde and the Anglo-Saxons, p. 27

- The description is Ó Corráin's, in R. Foster (ed.), The Oxford History of Ireland, p. 4.

- For a brief survey of Rome and southern Scotland see Hanson, "Roman occupation".

- The home of the Attacotti has been variously identified. Ireland is the most favoured location, and an association with the Déisi is plausible. A few authors have suggested the Outer Hebrides or the Northern Isles.

- Alcock & Alcock, "Excavations at Alt Clut"; Koch, "The Place of Y Gododdin". Barrell, Medieval Scotland, p. 44, supposes that the diocese of Glasgow established by David I in 1128 may have corresponded with the late kingdom of Strathclyde.

- Jackson, K.H. (1956) Language and History in Early Britain, Edinburgh: University of Edinburgh Press

- Smyth, Warlords and Holy Men represents a work where the Britons are given prominence, but others have concentrated on Dál Riata. At present, the division appears to be between Scots, Irish and "north British" scholars and Anglo-Saxonists. Leslie Alcock, Kings and Warriors, could be taken as representing a "north British (and Irish)" perspective.

- The Annals of the Four Masters associate Domnall Brecc of Dál Riata with these events.

- The Northumbrians in 684, the Picts in the 730s and the Dál Riata on many occasions.

- Stenton, Anglo-Saxon England, p. 320ff., in particular the claim at p. 322 that the first ten years of Edward's reign, say 899–902, saw no advances against the Danelaw.

- Duncan, Kingship of the Scots, pp. 23–24.

- No King of Strathclyde is named by the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle when Máel Coluim mac Cináeda, Mac Bethad and Echmarcach mac Ragnaill met with Canute in 1031.

- For this episode see Duncan, Kingship of the Scots, pp. 40–41.

- Charles-Edards, pp. 12, 575; Clarkson, pp. 12, 63–66, 154–58

Sources

- Alcock, Leslie, Kings and Warriors, Craftsmen and Priests in Northern Britain AD 550–850. Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, Edinburgh, 2003. ISBN 0-903903-24-5

- Barrell, A.D.M., Medieval Scotland. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2000. ISBN 0-521-58602-X

- Clarkson, Tim (2014). Strathclyde and the Anglo-Saxons in the Viking Age. Edinburgh: John Donald, Birlinn Ltd. ISBN 978 1 906566 78 4.

- Duncan, A.A.M., The Kingship of the Scots 842–1292: Succession and Independence. Edinburgh University Press, Edinburgh, 2002. ISBN 0-7486-1626-8

- Hanson, W.S., "Northern England and southern Scotland: Roman Occupation" in Michael Lynch (ed.), The Oxford Companion to Scottish History. Oxford UP, Oxford, 2001. ISBN 0-19-211696-7

- Koch, John, "The Place of 'Y Gododdin' in the History of Scotland" in Ronald Black, William Gillies and Roibeard Ó Maolalaigh (eds) Celtic Connections. Proceedings of the 10th International Congress of Celtic Studies, Volume One. Tuckwell, East Linton, 1999. ISBN 1-898410-77-1

- Smyth, Alfred P (1984). Warlords and Holy Men: Scotland AD 80–1000. Edward Arnold. ISBN 978-0-7131-6305-6.

- Stenton, Frank (1971). Anglo-Saxon England (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-280139-5.

Further reading

- Barrow, G.W.S., Kingship and Unity: Scotland 1000–1306. Edinburgh University Press, Edinburgh, (corrected edn) 1989. ISBN 0-7486-0104-X

- Broun, D. (2004). "The Welsh Identity of the Kingdom of Strathclyde c. 900–c. 1200". Innes Review (55): 111–80.

- Charles-Edwards, T. M. (2013). Wales and the Britons 350–1064. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-821731-2.

- Clarkson, Tim (2010). The Men of the North: The Britons of Southern Scotland. Edinburgh: John Donald, Birlinn Ltd. ISBN 978 1 906566 18 0.

- Edmonds, Fiona (October 2014). "The Emergence and Transformation of Medieval Cumbria". The Scottish Historical Review. XCIII, 2 (237): 195–216. doi:10.3366/shr.2014.0216.

- Edmonds, Fiona (2015). "The expansion of the kingdom of Strathclyde". Early Medieval Europe. 23: 43–66. doi:10.1111/emed.12087.

- Foster, Sally M., Picts, Gaels, and Scots: Early Historic Scotland. Batsford, London, 2nd edn, 2004. ISBN 0-7134-8874-3

- Higham, N.J., The Kingdom of Northumbria AD 350–1100. Sutton, Stroud, 1993. ISBN 0-86299-730-5

- Jackson, Kenneth H., "The Britons in southern Scotland" in Antiquity, vol. 29 (1955), pp. 77–88. ISSN 0003-598X .

- Lowe, Chris, Angels, Fools and Tyrants: Britons and Anglo-Saxons in Southern Scotland. Canongate, Edinburgh, 1999. ISBN 0-86241-875-5

- Woolf, Alex (2001). "Britons and Angles". In Lynch, Michael (ed.). The Oxford Companion to Scottish History. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199234820.

External links

- The Chronicle of the Kings of Alba

- The Rolls edition of the Brut y Tywyssogion (pdf) at Stanford University Library

- CELT: Corpus of Electronic Texts at University College Cork including the Annals of Ulster, the Annals of Tigernach and the Chronicon Scotorum.

- The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, manuscripts D and E, various editions including an XML version by Tony Jebson.

- Google Books includes the Chronicon ex chronicis attributed to Florence of Worcester and James Aikman's translation (The History of Scotland) of George Buchanan's Rerum Scoticarum Historia