Irish language

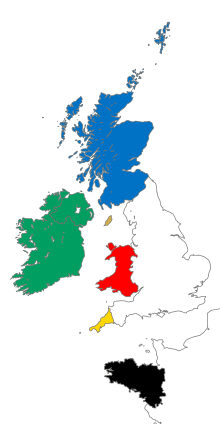

Irish (Standard Irish: Gaeilge) is a Goidelic language of the Celtic language family, itself a branch of the Indo-European language family. Irish originated in Ireland and was historically and still is spoken by Irish people throughout Ireland. Although English is the more common first language elsewhere in Ireland, Irish is spoken as a first language in substantial areas of counties Galway, Kerry, Cork and Donegal, as well as smaller areas of Waterford, Mayo and Meath. It is also spoken by a much larger group of habitual but non-traditional speakers across the country, mostly in urban areas where the majority are second language speakers.

| Irish | |

|---|---|

| Standard Irish: Gaeilge | |

| Pronunciation | [ˈɡeːlʲɟə] |

| Native to | Ireland |

| Ethnicity | Irish |

Native speakers | L1 speakers: 170,290 (2019)[1] L2 speakers: 1,761,420 answered “yes” to being able to speak Irish in the Republic of Ireland (2016), 104,943 identify as being able to speak Irish in Northern Ireland (2011), 18,815 Irish Americans claim to speak Irish at home (2005), Total: 2,055,468 |

Early forms | |

Standard forms | An Caighdeán Oifigiúil |

| Dialects |

|

| Latin (Irish alphabet) Irish Braille | |

| Official status | |

Official language in | |

| Regulated by | Foras na Gaeilge |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | ga |

| ISO 639-2 | gle |

| ISO 639-3 | gle |

| Glottolog | iris1253[2] |

| Linguasphere | 50-AAA |

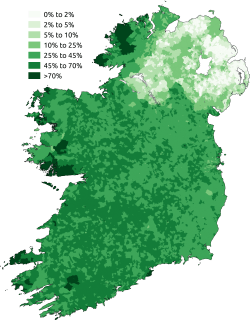

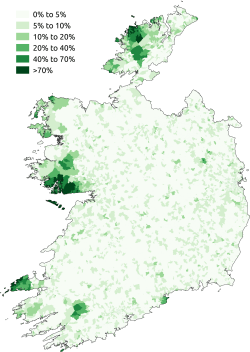

Proportion of respondents who said they could speak Irish in the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland censuses of 2011. | |

Irish was the dominant language of the Irish people for most of their recorded history, and they took it with them to other regions, notably Scotland and the Isle of Man, where Middle Irish gave rise to Scottish Gaelic and Manx respectively. It has the oldest vernacular literature in Western Europe.

Irish has constitutional status as the national and first official language of the Republic of Ireland and is an officially recognised minority language in Northern Ireland. It is also among the official languages of the European Union. The public body Foras na Gaeilge is responsible for the promotion of the language throughout the island of Ireland.

Names

In Irish

In An Caighdeán Oifigiúil (the official written standard) the name of the language – in the Irish language – is Gaeilge (Irish pronunciation: [ˈɡeːlʲɟə]), this being in origin the Connacht form. Before the spelling reform of 1948, this form was spelled Gaedhilge; originally this was the genitive of Gaedhealg, the form used in Classical Gaelic.[3] Older spellings of this include Gaoidhealg [ˈɡeːʝəlˠɡ] in Classical Gaelic and Goídelc [ˈɡoiðelˠɡ] in Old Irish. The modern spelling results from the deletion of the silent dh in the middle of Gaedhilge, whereas Goidelic, used to refer to the language family including Irish, is derived from the Old Irish term.

Other forms of the name found in the various modern Irish dialects (in addition to south Connacht Gaeilge above) include Gaedhilic/Gaeilic/Gaeilig [ˈɡeːlʲɪc] or Gaedhlag [ˈɡeːlˠəɡ] in Ulster Irish and northern Connacht Irish and Gaedhealaing [ˈɡeːl̪ˠɪɲ] or Gaoluinn/Gaelainn [ˈɡeːl̪ˠɪnʲ][4][5] in Munster Irish.

In English

The English word for the language is Irish, which is defined by the European Union as "the Celtic language of Ireland". According to the EU, the "two terms [Irish and Gaelic] are not synonymous"; it defines Gaelic as the "Celtic language group of Ireland and Scotland".[6] This is concurrent with definitions of the term Gaelic in both the Cambridge and the Merriam-Webster dictionaries.[7][8]

Alan Titley, an Irish translator and Emeritus Professor of Modern Irish at University College Cork, has illuminated the distinction between the terms "Irish" and "Gaelic" in the following terms:

"Irish" is sometimes erroneously referred to as "Gaelic." The Irish language should never be referred to as "Gaelic" because doing so is historically, socially, formally, and linguistically wrong. "Gaelic" is now correctly applied to the principal historic language of Scotland, although it also was referred to (in English) as "Irish" for most of its history. The distinction is not subtle: "Irish" refers to the native language of Ireland, and "Gaelic" refers to the major native language of Scotland, although the term came into common usage only in the past two hundred years, or less.[9][10]

— Alan Titley, in the translator's introduction of The Dirty Dust (2015), p. viii.

History

Written Irish is first attested in Ogham inscriptions from the 4th century AD, a stage of the language known as Primitive Irish. These writings have been found throughout Ireland and the west coast of Great Britain. Primitive Irish transitioned into Old Irish through the 5th century. Old Irish, dating from the 6th century, used the Latin alphabet and is attested primarily in marginalia to Latin manuscripts. During this time, the Irish language absorbed some Latin words, some via Old Welsh, including ecclesiastical terms: examples are easpag (bishop) from episcopus, and Domhnach (Sunday, from dominica).

By the 10th century, Old Irish had evolved into Middle Irish, which was spoken throughout Ireland and in Scotland and the Isle of Man. It is the language of a large corpus of literature, including the Ulster Cycle. From the 12th century, Middle Irish began to evolve into modern Irish in Ireland, into Scottish Gaelic in Scotland, and into the Manx language in the Isle of Man.

Early Modern Irish, dating from the 13th century, was the basis of the literary language of both Ireland and Gaelic-speaking Scotland. Modern Irish, as attested in the work of such writers as Geoffrey Keating, may be said to date from the 17th century, and was the medium of popular literature from that time on.

From the 18th century on, the language lost ground in the east of the country. The reasons behind this shift were complex but came down to a number of factors:

- Discouragement of its use by Anglo-British administrations.

- The Catholic church supporting the use of English over Irish.

- The spread of bilingualism from the 1750s, resulting in language shift.[11]

It was a change characterised by diglossia (two languages being used by the same community in different social and economic situations) and transitional bilingualism (monoglot Irish-speaking grandparents with bilingual children and monoglot English-speaking grandchildren). By the mid-18th century, English was becoming a language of the Catholic middle class, the Catholic Church and public intellectuals, especially in the east of the country. Increasingly, as the value of English became apparent, the prohibition on Irish in schools had the sanction of parents.[12] Once it became apparent that emigration to the United States and Canada was likely for a large portion of the population, the importance of learning English became relevant. This allowed the new immigrants to get jobs in areas other than farming. It has been estimated that, due to the immigration to the United States because of the Famine, anywhere from a quarter to a third of the immigrants were Irish speakers.[13]

Irish was not marginal to Ireland's modernisation in the 19th century, as often assumed. In the first half of the century there were still around three million people for whom Irish was the primary language, and their numbers alone made them a cultural and social force. Irish speakers often insisted on using the language in law courts (even when they knew English), and Irish was also common in commercial transactions. The language was heavily implicated in the "devotional revolution" which marked the standardisation of Catholic religious practice and was also widely used in a political context. Down to the time of the Great Famine and even afterwards, the language was in use by all classes, Irish being an urban as well as a rural language.[14]

This linguistic dynamism was reflected in the efforts of certain public intellectuals to counter the decline of the language. At the end of the 19th century, they launched the Gaelic revival in an attempt to encourage the learning and use of Irish, although few adult learners mastered the language.[15] The vehicle of the revival was the Gaelic League (Conradh na Gaeilge), and particular emphasis was placed on the folk tradition, which in Irish is particularly rich. Efforts were also made to develop journalism and a modern literature.

Although it has been noted that the Catholic Church played a role in the decline of the Irish language before the Gaelic Revival, the Protestant Church of Ireland also made only minor efforts to encourage use of Irish in a religious context. An Irish translation of the Old Testament by Leinsterman Muircheartach Ó Cíonga, commissioned by Bishop Bedell, was published after 1685 along with a translation of the New Testament. Otherwise, Anglicisation was seen as synonymous with 'civilising'" of the native Irish. Currently, modern day Irish speakers in the church are pushing for language revival.[16]

Current status

Republic of Ireland

Irish is recognised by the Constitution of Ireland as the national and first official language of the Republic of Ireland (English being the other official language). Despite this, almost all government debates and business are conducted in English.[17] In 1938, the founder of Conradh na Gaeilge (Gaelic League), Douglas Hyde, was inaugurated as the first President of Ireland. The record of his delivering his inaugural Declaration of Office in Roscommon Irish is one of only a few recordings of that dialect.[18][19][20][21]

In the 2016 census, 10.5% of respondents stated that they spoke Irish, either daily or weekly, while over 70,000 people (4.2%) speak it as a habitual daily means of communication.[22]

From the foundation of the Irish Free State in 1922 (see also History of the Republic of Ireland), a degree of proficiency in Irish was required of all those newly appointed to the Civil Service of the Republic of Ireland, including postal workers, tax collectors, agricultural inspectors, Garda Síochána, etc. By law if a Garda was stopped and addressed in Irish he had to respond in Irish as well.[23] Proficiency in just one official language for entrance to the public service was introduced in 1974, in part through the actions of protest organisations like the Language Freedom Movement.

Although the Irish requirement was also dropped for wider public service jobs, Irish remains a required subject of study in all schools within the Republic which receive public money (see also Education in the Republic of Ireland). Those wishing to teach in primary schools in the State must also pass a compulsory examination called Scrúdú Cáilíochta sa Ghaeilge. The need for a pass in Leaving Certificate Irish or English for entry to the Garda Síochána (police) was introduced in September 2005, and recruits are given lessons in the language during their two years of training. The most important official documents of the Irish government must be published in both Irish and English or Irish alone (in accordance with the Official Languages Act 2003, enforced by An Coimisinéir Teanga, the Irish language ombudsman).

The National University of Ireland requires all students wishing to embark on a degree course in the NUI federal system to pass the subject of Irish in the Leaving Certificate or GCE/GCSE examinations.[24] Exemptions are made from this requirement for students born outside of the Republic of Ireland, those who were born in the Republic but completed primary education outside it, and students diagnosed with dyslexia. NUI Galway is required to appoint people who are competent in the Irish language, as long as they are also competent in all other aspects of the vacancy to which they are appointed. This requirement is laid down by the University College Galway Act, 1929 (Section 3).[25] The University faced controversy, however, in 2016 when it was announced that the next president of the University would not have any Irish language ability. Misneach staged a number of protests against this decision. It was announced in September 2017 that Ciarán Ó hÓgartaigh, a fluent Irish speaker, would be NUIG's 13th president.

For a number of years there has been vigorous debate in political, academic and other circles about the failure of most students in mainstream (English-medium) schools to achieve competence in the language, even after fourteen years of school instruction.[26][27][28] The concomitant decline in the number of traditional native speakers has also been a cause of great concern.[29][30][31][32] In 2007, filmmaker Manchán Magan found few speakers and some incredulity while speaking only Irish in Dublin. He was unable to accomplish some everyday tasks, as portrayed in his documentary No Béarla.[33]

There is, however, a growing body of Irish speakers in urban areas, particularly in Dublin. Many have been educated in schools in which Irish is the language of instruction: such schools are known as Gaelscoileanna at primary level. These Irish-medium schools send a much higher proportion of pupils on to third-level education than do "mainstream" schools, and it seems increasingly possible that, within a generation, non-Gaeltacht habitual users of Irish will typically be members of an urban, middle class and highly educated minority.[34]

Parliamentary legislation is supposed to be available in both Irish and English but is frequently only available in English. This is notwithstanding that Article 25.4 of the Constitution of Ireland requires that an "official translation" of any law in one official language be provided immediately in the other official language, if not already passed in both official languages.[35]

In November 2016, it was reported that many people worldwide were learning Irish through the Duolingo app.[36] Irish president Michael Higgins officially honoured several volunteer translators for developing the Irish edition, and said the push for Irish language rights remains an "unfinished project".[37]

Gaeltacht

There are rural areas of Ireland where Irish is still spoken daily to some extent as a first language. These regions are known individually and collectively as the Gaeltacht, or in the plural as Gaeltachtaí. While the Gaeltacht's fluent Irish speakers, whose numbers have been estimated at twenty or thirty thousand,[38] are a minority of the total number of fluent Irish speakers, they represent a higher concentration of Irish speakers than other parts of the country and it is only in Gaeltacht areas that Irish continues, to some extent, to be spoken as a community vernacular.

According to data compiled by the Department of Culture, Heritage and the Gaeltacht, only one quarter of households in officially Gaeltacht areas are fluent in Irish. The author of a detailed analysis of the survey, Donncha Ó hÉallaithe of the Galway-Mayo Institute of Technology, described the Irish language policy followed by Irish governments as a "complete and absolute disaster". The Irish Times, referring to his analysis published in the Irish language newspaper Foinse, quoted him as follows: "It is an absolute indictment of successive Irish Governments that at the foundation of the Irish State there were 250,000 fluent Irish speakers living in Irish-speaking or semi Irish-speaking areas, but the number now is between 20,000 and 30,000".[38]

In the 1920s, when the Irish Free State was founded, Irish was still a vernacular in some western coastal areas.[39] In the 1930s, areas where more than 25% of the population spoke Irish were classified as Gaeltacht. Today, the strongest Gaeltacht areas, numerically and socially, are those of South Connemara, the west of the Dingle Peninsula and northwest Donegal, where many residents still use Irish as their primary language. These areas are often referred to as the Fíor-Ghaeltacht ("true Gaeltacht"), a term originally officially applied to areas where over 50% of the population spoke Irish.

There are larger Gaeltacht regions in County Galway (Contae na Gaillimhe), including Connemara (Conamara), the Aran Islands (Oileáin Árann), Carraroe (An Cheathrú Rua) and Spiddal (An Spidéal), on the west coast of County Donegal (Contae Dhún na nGall), and on the Dingle (Corca Dhuibhne) and Iveragh Peninsulas (Uibh Rathach) in County Kerry (Contae Chiarraí).

Smaller ones also exist in Counties Mayo (Contae Mhaigh Eo), Meath (Contae na Mí), Waterford (Gaeltacht na nDéise, Contae Phort Láirge), and Cork (Contae Chorcaí). Gweedore (Gaoth Dobhair), County Donegal, is the largest Gaeltacht parish in Ireland.

Irish language summer colleges in the Gaeltacht are attended by tens of thousands of teenagers annually. Students live with Gaeltacht families, attend classes, participate in sports, go to céilithe and are obliged to speak Irish. All aspects of Irish culture and tradition are encouraged.

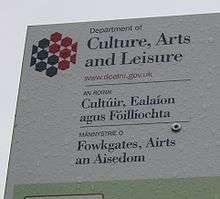

Northern Ireland

Before the partition of Ireland in 1921, Irish was recognised as a school subject and as "Celtic" in some third level institutions. Between 1921 and 1972, Northern Ireland had devolved government. During those years the political party holding power in the Stormont Parliament, the Ulster Unionist Party (UUP), was hostile to the language. The context of this hostility was the use of the language by nationalists.[40] In broadcasting, there was an exclusion on the reporting of minority cultural issues, and Irish was excluded from radio and television for almost the first fifty years of the previous devolved government.[41] The language received a degree of formal recognition in Northern Ireland from the United Kingdom, under the 1998 Good Friday Agreement,[42] and then, in 2003, by the British government's ratification in respect of the language of the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. In the 2006 St Andrews Agreement the British government promised to enact legislation to promote the language[43] but as of 2019 it has yet to do so.[44] The Irish language has often been used as a bargaining chip during government formation in Northern Ireland, prompting protests from organisations and groups such as An Dream Dearg. There is currently an ongoing debate in relation to the status of the language in the form of an Irish Language Act. An Dream Dearg have launched a campaign in favour of such an Act called Acht na Gaeilge Anois ("Irish Language Act Now").[45]

European Parliament

Irish became an official language of the EU on 1 January 2007, meaning that MEPs with Irish fluency can now speak the language in the European Parliament and at committees, although in the case of the latter they have to give prior notice to a simultaneous interpreter in order to ensure that what they say can be interpreted into other languages. While an official language of the European Union, only co-decision regulations must be available in Irish for the moment, due to a renewable five-year derogation on what has to be translated, requested by the Irish Government when negotiating the language's new official status. Any expansion in the range of documents to be translated will depend on the results of the first five-year review and on whether the Irish authorities decide to seek an extension. The Irish government has committed itself to train the necessary number of translators and interpreters and to bear the related costs.[46] Derogation is expected to end completely by 2022.[47]

Before Irish became an official language it was afforded the status of treaty language and only the highest-level documents of the EU were made available in Irish.

Outside Ireland

The Irish language was carried abroad in the modern period by a vast diaspora, chiefly to Great Britain and North America, but also to Australia, New Zealand and Argentina. The first large movements began in the 17th century, largely as a result of the Cromwellian conquest of Ireland, which saw many Irish sent to the West Indies. Irish emigration to the United States was well established by the 18th century, and was reinforced in the 1840s by thousands fleeing from the Famine. This flight also affected Britain. Up until that time most emigrants spoke Irish as their first language, though English was establishing itself as the primary language. Irish speakers had first arrived in Australia in the late 18th century as convicts and soldiers, and many Irish-speaking settlers followed, particularly in the 1860s. New Zealand also received some of this influx. Argentina was the only non-English-speaking country to receive large numbers of Irish emigrants, and there were few Irish speakers among them.

Relatively few of the emigrants were literate in Irish, but manuscripts in the language were brought to both Australia and the United States, and it was in the United States that the first newspaper to make significant use of Irish was established: An Gaodhal. In Australia, too, the language found its way into print. The Gaelic revival, which started in Ireland in the 1890s, found a response abroad, with branches of Conradh na Gaeilge being established in all the countries to which Irish speakers had emigrated.

The decline of Irish in Ireland and a slowing of emigration helped to ensure a decline in the language abroad, along with natural attrition in the host countries. Despite this, small groups of enthusiasts continued to learn and cultivate Irish in diaspora countries and elsewhere, a trend which strengthened in the second half of the 20th century. Today the language is taught at tertiary level in North America, Australia and Europe, and Irish speakers outside Ireland contribute to journalism and literature in the language. There are significant Irish-speaking networks in the United States and Canada;[48] figures released for the period 2006–2008 show that 22,279 Irish Americans claimed to speak Irish at home.[49]

The Irish language is also one of the languages of the Celtic League, a non-governmental organisation that promotes self-determination and Celtic identity and culture in Ireland, Scotland, Wales, Brittany, Cornwall and the Isle of Man, known as the Celtic nations. It places particular emphasis on the indigenous Celtic languages. It is recognised by the United Nations as a non-governmental organisation with "Roster Status" and is part of the UN's Economic and Social Council. The organisation has branches in all the Celtic nations and in Patagonia, Argentina, New York City, US, and London, UK.

Irish was spoken as a community language until the early 20th century on the island of Newfoundland, in a form known as Newfoundland Irish.

Use

The following 2016 census data shows:

The total number of people who answered 'yes' to being able to speak Irish in April 2016 was 1,761,420, a slight decrease (0.7 per cent) on the 2011 figure of 1,774,437. This represents 39.8 per cent of respondents compared with 41.4 in 2011... Of the 73,803 daily Irish speakers (outside the education system), 20,586 (27.9%) lived in Gaeltacht areas.

Daily Irish speakers in Gaeltacht areas between 2011 and 2016

| Gaeltacht Area | 2011 | 2016 | Change 2011/2016 | Change 2011/2016 (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cork County | 982 | 872 | |||||||

| Donegal County | 7,047 | 5,929 | |||||||

| Galway City | 636 | 646 | |||||||

| Galway County | 10,085 | 9,445 | |||||||

| Kerry County | 2,501 | 2,049 | |||||||

| Mayo County | 1,172 | 895 | |||||||

| Meath County | 314 | 283 | |||||||

| Waterford County | 438 | 467 | |||||||

| All Gaeltacht Areas | 23,175 | 20,586 | |||||||

Source:[50] | |||||||||

In 1996, the 3 electoral divisions in the State where Irish has the most daily speakers were An Turloch (91%+),Scainimh (89%+), Min an Chladaigh (88%+).[51]

Dialects

Irish is represented by several traditional dialects and by various varieties of "urban" Irish. The latter have acquired lives of their own and a growing number of native speakers. Differences between the dialects make themselves felt in stress, intonation, vocabulary and structural features.

Roughly speaking, the three major dialect areas which survive coincide roughly with the provinces of Munster (Cúige Mumhan), Connacht (Cúige Chonnacht) and Ulster (Cúige Uladh). Records of some dialects of Leinster (Cúige Laighean) were made by the Irish Folklore Commission and others.[52] Newfoundland, in eastern Canada, had a form of Irish derived from the Munster Irish of the later 18th century (see Newfoundland Irish).

Munster

Munster Irish is the dialect spoken in the Gaeltacht areas of the three counties Cork (Contae Chorcaí), Kerry (Contae Chiarraí), Waterford (Contae Phort Láirge). The Gaeltacht areas of Cork can be found in Cape Clear Island (Oileán Chléire) and Muskerry (Múscraí); those of Kerry lie in Corca Dhuibhne and Iveragh Peninsula; and those of Waterford in Ring (An Rinn) and Old Parish (An Sean Phobal), both of which together form Gaeltacht na nDéise. Of the three counties, the Irish spoken in Cork and Kerry are quite similar while that of Waterford is more distinct.

Some typical features of Munster Irish are:

- The use of endings to show person on verbs in parallel with a pronominal subject system, thus "I must" is in Munster caithfead as well as caithfidh mé, while other dialects prefer caithfidh mé (mé means "I"). "I was and you were" is Bhíos agus bhís as well as Bhí mé agus bhí tú in Munster, but more commonly Bhí mé agus bhí tú in other dialects. Note that these are strong tendencies, and the personal forms Bhíos etc. are used in the West and North, particularly when the words are last in the clause.

- Use of independent/dependent forms of verbs that are not included in the Standard. For example, "I see" in Munster is chím, which is the independent form – Ulster Irish also uses a similar form, tchím), whereas "I do not see" is ní fheicim, feicim being the dependent form, which is used after particles such as ní "not"). Chím is replaced by feicim in the Standard. Similarly, the traditional form preserved in Munster bheirim I give/ní thugaim is tugaim/ní thugaim in the Standard; gheibhim I get/ní bhfaighim is faighim/ní bhfaighim.

- When before -nn, -m, -rr, -rd, -ll and so on, in monosyllabic words and in the stressed syllable of multisyllabic words where the syllable is followed by a consonant, some short vowels are lengthened while others are diphthongised, thus ceann [caun] "head", cam [kɑum] "crooked", gearr [ɟaːr] "short", ord [oːrd] "sledgehammer", gall [ɡɑul] "foreigner, non-Gael", iontas [uːntəs] "a wonder, a marvel", compánach [kəumˈpɑːnəx] "companion, mate", etc.

- A copular construction involving ea "it" is frequently used. Thus "I am an Irish person" can be said is Éireannach mé and Éireannach is ea mé in Munster; there is a subtle difference in meaning, however, the first choice being a simple statement of fact, while the second brings emphasis onto the word Éireannach. In effect the construction is a type of "fronting".

- Both masculine and feminine words are subject to lenition after insan (sa/san) "in the", den "of the" and don "to/for the" : sa tsiopa, "in the shop", compared to the Standard sa siopa (the Standard lenites only feminine nouns in the dative in these cases).

- Eclipsis of f after sa: sa bhfeirm, "in the farm", instead of san fheirm.

- Eclipsis of t and d after preposition + singular article, with all prepositions except after insan, den and don: ar an dtigh "on the house", ag an ndoras "at the door".

- Stress falls in general found on the second syllable of a word when the first syllable contains a short vowel, and the second syllable contains a long vowel, diphthong, or is -(e)ach, e.g. biorán ("pin"), as opposed to biorán in Connacht and Ulster.

Connacht

Historically, Connacht Irish represents the westernmost remnant of a dialect area which once stretched from east to west across the centre of Ireland. The strongest dialect of Connacht Irish is to be found in Connemara and the Aran Islands. Much closer to the larger Connacht Gaeltacht is the dialect spoken in the smaller region on the border between Galway (Gaillimh) and Mayo (Maigh Eo). There are a number of differences between the popular South Connemara form of Irish, the Mid-Connacht/Joyce Country form (on the border between Mayo and Galway) and the Achill and Erris forms in the north of the province.

Features in Connacht Irish differing from the official standard include a preference for verbal nouns ending in -achan, e.g. lagachan instead of lagú, "weakening". The non-standard pronunciation of the Gaeltacht Cois Fharraige area with lengthened vowels and heavily reduced endings gives it a distinct sound. Distinguishing features of Connacht and Ulster dialect include the pronunciation of word-final broad bh and mh as [w], rather than as [vˠ] in Munster. For example, sliabh ("mountain") is pronounced [ʃlʲiəw] in Connacht and Ulster as opposed to [ʃlʲiəβ] in the south. In addition Connacht and Ulster speakers tend to include the "we" pronoun rather than use the standard compound form used in Munster, e.g. bhí muid is used for "we were" instead of bhíomar.

As in Munster Irish, some short vowels are lengthened and others diphthongised before -nn, -m, -rr, -rd, -ll, in monosyllabic words and in the stressed syllable of multisyllabic words where the syllable is followed by a consonant. This can be seen in ceann [cɑ:n] "head", cam [kɑ:m] "crooked", gearr [gʲɑ:r] "short", ord [ourd] "sledgehammer", gall [gɑ:l] "foreigner, non-Gael", iontas [i:ntəs] "a wonder, a marvel", etc. The form '-aibh', when occurring at the end of words like 'agaibh', tends to be pronounced as an 'ee' sound.

In South Connemara, for example, there is a tendency to substitute a "b" sound at the end of words ending in "bh" [β], such as sibh, libh and dóibh, something not found in the rest of Connacht (these words would be pronounced respectively as "shiv," "liv" and "dófa" in the other areas). This placing of the B-sound is also present at the end of words ending in vowels, such as acu (pronounced as "acub") and leo (pronounced as "lyohab"). There is also a tendency to omit the "g" sound in words such as agam, agat and againn, a characteristic also of other Connacht dialects. All these pronunciations are distinctively regional.

The pronunciation prevalent in the Joyce Country (the area around Lough Corrib and Lough Mask) is quite similar to that of South Connemara, with a similar approach to the words agam, agat and againn and a similar approach to pronunciation of vowels and consonants. But there are noticeable differences in vocabulary, with certain words such as doiligh (difficult) and foscailte being preferred to the more usual deacair and oscailte. Another interesting aspect of this sub-dialect is that almost all vowels at the end of words tend to be pronounced as í: eile (other), cosa (feet) and déanta (done) tend to be pronounced as eilí, cosaí and déantaí respectively.

The northern Mayo dialect of Erris (Iorras) and Achill (Acaill) is in grammar and morphology essentially a Connacht dialect, but shows some similarities to Ulster Irish due to large-scale immigration of dispossessed people following the Plantation of Ulster. For example, words ending -mh and -bh have a much softer sound, with a tendency to terminate words such as leo and dóibh with "f", giving leofa and dófa respectively. In addition to a vocabulary typical of other area of Connacht, one also finds Ulster words like amharc (meaning "to look" and pronounced "onk"), nimhneach (painful or sore), druid (close), mothaigh (hear), doiligh (difficult), úr (new), and tig le (to be able to – i.e. a form similar to féidir).

Irish President Douglas Hyde was possibly one of the last speakers of the Roscommon dialect of Irish.[19]

Ulster

Ulster Irish is the dialect spoken in the Gaeltacht regions of Donegal. These regions contain all of Ulster's communities where Irish has been spoken in an unbroken line back to when the language was the dominant language of Ireland. The Irish-speaking communities in other parts of Ulster are a result of language revival – English-speaking families deciding to learn Irish. Census data shows that 4,130 people speak it at home.

Linguistically, the most important of the Ulster dialects today is that which is spoken, with slight differences, in both Gweedore (Gaoth Dobhair = Inlet of Streaming Water) and The Rosses (na Rossa). Natives of Gweedore include singers Enya (Eithne) and Moya Brennan and their siblings in Clannad (Clann as Dobhar = Family from the Dobhar [a section of Gweedore]) Na Casaidigh, and Mairéad Ní Mhaonaigh from another local band Altan. Natives of The Rosses include the literary brothers Séamus Ó Grianna and Seosamh Mac Grianna, locally known as Jimí Fheilimí and Joe Fheilimí.

Ulster Irish sounds quite different from the other two main dialects. It shares several features with southern dialects of Scottish Gaelic and Manx, as well as having many characteristic words and shades of meanings. However, since the demise of those Irish dialects spoken natively in what is today Northern Ireland, it is probably an exaggeration to see present-day Ulster Irish as an intermediary form between Scottish Gaelic and the southern and western dialects of Irish. Northern Scottish Gaelic has many non-Ulster features in common with Munster Irish.

One noticeable trait of Ulster Irish, Scots Gaelic and Manx is the use of the negative particle cha(n) in place of the Munster and Connacht ní. Though southern Donegal Irish tends to use ní more than cha(n), cha(n) has almost ousted ní in northernmost dialects (e.g. Rosguill and Tory Island), though even in these areas níl "is not" is more common than chan fhuil or cha bhfuil.[53][54] Another noticeable trait is the pronunciation of the first person singular verb ending -im as -am, also common to Man and Scotland (Munster/Connacht siúlaim "I walk", Ulster siúlam).

Leinster

Down to the early 19th century and even later, Irish was spoken in all twelve counties of Leinster. The evidence furnished by placenames, literary sources and recorded speech indicates that there was no Leinster dialect as such. Instead, the main dialect used in the province was represented by a broad central belt stretching from west Connacht eastwards to the Liffey estuary and southwards to Wexford, though with many local variations. Two smaller dialects were represented by the Ulster speech of counties Meath and Louth, which extended as far south as the Boyne valley, and a Munster dialect found in Kilkenny and south Laois.

The main dialect had characteristics which survive today only in the Irish of Connacht. It typically placed the stress on the first syllable of a word, and showed a preference (found in placenames) for the pronunciation cr where the standard spelling is cn. The word cnoc (hill) would therefore be pronounced croc. Examples are the placenames Crooksling (Cnoc Slinne) in County Dublin and Crukeen (Cnoicín) in Carlow. East Leinster showed the same diphthongisation or vowel lengthening as in Munster and Connacht Irish in words like poll (hole), cill (monastery), coill (wood), ceann (head), cam (crooked) and dream (crowd). A feature of the dialect was the pronunciation of the vowel ao, which generally became ae in east Leinster (as in Munster), and í in the west (as in Connacht).[55]

Early evidence regarding colloquial Irish in east Leinster is found in The Fyrst Boke of the Introduction of Knowledge (1547), by the English physician and traveller Andrew Borde.[56] The illustrative phrases he uses include the following (with regularised Irish spelling in brackets):

| How are you? | Kanys stato? | [Canas 'tá tú?] |

| I am well, thank you | Tam a goomah gramahagood. | [Tá mé go maith, go raibh maith agat.] |

| Syr, can you speak Iryshe? | Sor, woll galow oket? | [Sir, 'bhfuil Gaeilig [Gaela'] agat?] |

| Wyfe, gyve me bread! | Benytee, toor haran! | [A bhean an tí, tabhair arán!] |

| How far is it to Waterford? | Gath haad o showh go part laarg?. | [Gá fhad as [a] seo go Port Láirge?] |

| It is one an twenty myle. | Myle hewryht. | [Míle a haon ar fhichid.] |

| Whan shal I go to slepe, wyfe? | Gah hon rah moyd holow? | [Gathain a rachamaoid a chodladh?] |

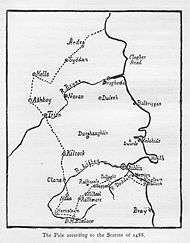

The Pale

The Pale (An Pháil) was an area around late medieval Dublin under the control of the English government. By the late 15th century it consisted of an area along the coast from Dalkey, south of Dublin, to the garrison town of Dundalk, with an inland boundary encompassing Naas and Leixlip in the Earldom of Kildare and Trim and Kells in County Meath to the north. In this area of "Englyshe tunge" English had never actually been a dominant language – and was moreover a relatively late comer; the first colonisers were Normans who spoke Norman French, and before these Norse. The Irish language had always been the language of the bulk of the population. An English official remarked of the Pale in 1515 that "all the common people of the said half counties that obeyeth the King's laws, for the most part be of Irish birth, of Irish habit and of Irish language".[57]

With the strengthening of English cultural and political control, language change began to occur, but this did not become clearly evident until the 18th century. Even then, in the decennial period 1771–81, the percentage of Irish speakers in Meath was at least 41%. By 1851 this had fallen to less than 3%.[58]

General decline

English expanded strongly in Leinster in the 18th century, but Irish speakers were still numerous. In the decennial period 1771–81 certain counties had estimated percentages of Irish speakers as follows (though the estimates are likely to be too low):[58]

- Kilkenny 57%

- Louth 57%

- Longford 22%

- Westmeath 17%

The language saw its most rapid initial decline in Laois, Wexford, Wicklow, County Dublin and perhaps Kildare. The proportion of Irish-speaking children in Leinster went down as follows: 17% in the 1700s, 11% in the 1800s, 3% in the 1830s and virtually none in the 1860s.[59]

The Irish census of 1851 showed that there were still a number of older speakers in County Dublin.[58] Sound recordings were made between 1928 and 1931 of some of the last speakers in Omeath, County Louth (now available in digital form).[60] The last known traditional native speaker in Omeath, and in Leinster as a whole, was Annie O'Hanlon (née Dobbin), who died in 1960.[12]

Urban use from the middle ages to the 19th century

Irish was spoken as a community language in Irish towns and cities down to the 19th century. In the 16th and 17th centuries it was widespread even in Dublin and the Pale. The English administrator William Gerard (1518–1581) commented as follows: "All Englishe, and the most part with delight, even in Dublin, speak Irishe,"[61] while the Old English historian Richard Stanihurst (1547–1618) lamented that "When their posteritie became not altogither so warie in keeping, as their ancestors were valiant in conquering, the Irish language was free dennized in the English Pale: this canker tooke such deep root, as the bodie that before was whole and sound, was by little and little festered, and in manner wholly putrified".[62]

The Irish of Dublin, situated as it was between the east Ulster dialect of Meath and Louth to the north and the Leinster-Connacht dialect further south, may have reflected the characteristics of both in phonology and grammar. In County Dublin itself the general rule was to place the stress on the initial vowel of words. With time it appears that the forms of the dative case took over the other case endings in the plural (a tendency found to a lesser extent in other dialects). In a letter written in Dublin in 1691 we find such examples as the following: gnóthuimh (accusative case, the standard form being gnóthaí), tíorthuibh (accusative case, the standard form being tíortha) and leithscéalaibh (genitive case, the standard form being leithscéalta).[63]

English authorities of the Cromwellian period, aware that Irish was widely spoken in Dublin, arranged for its official use. In 1655 several local dignitaries were ordered to oversee a lecture in Irish to be given in Dublin. In March 1656 a converted Catholic priest, Séamas Corcy, was appointed to preach in Irish at Bride's parish every Sunday, and was also ordered to preach at Drogheda and Athy.[64] In 1657 the English colonists in Dublin presented a petition to the Municipal Council complaining that in Dublin itself "there is Irish commonly and usually spoken".[65]

There is contemporary evidence of the use of Irish in other urban areas at the time. In 1657 it was found necessary to have an Oath of Abjuration (rejecting the authority of the Pope) read in Irish in Cork so that people could understand it.[66]

Irish was sufficiently strong in early 18th century Dublin to be the language of a coterie of poets and scribes led by Seán and Tadhg Ó Neachtain, both poets of note.[67] Scribal activity in Irish persisted in Dublin right through the 18th century. An outstanding example was Muiris Ó Gormáin (Maurice Gorman), a prolific producer of manuscripts who advertised his services (in English) in Faulkner's Dublin Journal.[68] There were still an appreciable number of Irish speakers in County Dublin at the time of the 1851 census.[69]

In other urban centres the descendants of medieval Anglo-Norman settlers, the so-called Old English, were Irish-speaking or bilingual by the 16th century.[70] The English administrator and traveller Fynes Moryson, writing in the last years of the 16th century, said that "the English Irish and the very citizens (excepting those of Dublin where the lord deputy resides) though they could speak English as well as we, yet commonly speak Irish among themselves, and were hardly induced by our familiar conversation to speak English with us".[71] In Galway, a city dominated by Old English merchants and loyal to the Crown up to the Irish Confederate Wars (1641–1653), the use of the Irish language had already provoked the passing of an Act of Henry VIII (1536), ordaining as follows:

- Item, that every inhabitant within oure said towne [Galway] endeavour themselfes to speake English, and to use themselfes after the English facon; and, speciallye, that you, and every one of you, doe put your children to scole, to lerne to speke English...[72]

The demise of native cultural institutions in the seventeenth century saw the social prestige of Irish diminish, and the gradual Anglicisation of the middle classes followed.[73] The census of 1851 showed, however, that the towns and cities of Munster still had significant Irish-speaking populations. Much earlier, in 1819, James McQuige, a veteran Methodist lay preacher in Irish, wrote: "In some of the largest southern towns, Cork, Kinsale and even the Protestant town of Bandon, provisions are sold in the markets, and cried in the streets, in Irish".[74] Irish speakers constituted over 40% of the population of Cork even in 1851.[75]

Modern urban Irish

The 19th century saw a reduction in the number of Dublin's Irish speakers, in keeping with the trend elsewhere. This continued until the end of the century, when the Gaelic revival saw the creation of a strong Irish–speaking network, typically united by various branches of the Conradh na Gaeilge, and accompanied by renewed literary activity.[76] By the 1930s Dublin had a lively literary life in Irish.[77]

Urban Irish has been the beneficiary, over the last few decades, of a rapidly expanding independent school system, known generally as Gaelscoileanna, teaching entirely through Irish. As of 2019 there are 37 such primary schools in Dublin alone.[78]

It has been suggested that Ireland's towns and cities are acquiring a critical mass of Irish speakers, reflected in the expansion of Irish language media.[79] Many are younger speakers who, after encountering Irish at school, made an effort to acquire fluency; others have been educated through Irish; some have been raised with Irish. Those from an English-speaking background are now often described as "nuachainteoirí" (new speakers) and use whatever opportunities are available (festivals, "pop-up" events) to practise or improve their Irish.[80] They vary in fluency, but the comparative standard is still the Irish of the Gaeltacht.[81] Such a comparison shows that the distinction between broad and slender consonants, which is fundamental to Irish phonology and grammar, is not fully or consistently observed in urban Irish, perhaps due to aspects of the learning process. This and other changes make it possible that urban Irish will become a new dialect or even, over a long period, develop into a creole (i.e. a new language) distinct from Gaeltacht Irish.[79]

It has been argued that there is a certain elitism among Irish speakers, with most respect being given to the Irish of native Gaeltacht speakers and with "Dublin" (i.e. urban) Irish being under-represented in the media.[82] This, however, is paralleled by a failure among some urban Irish speakers to acknowledge grammatical and phonological features essential to the structure of the language.[79]

Towards a standard Irish – An Caighdeán Oifigiúil

There is no single official standard for pronouncing the Irish language. Certain dictionaries, such as Foclóir Póca, provide a single pronunciation. Online dictionaries such as Foclóir Béarla-Gaeilge[83] provide audio files in the three major dialects, although the recordings are not made by native speakers and are thus often inaccurate representations of the dialectal phonological variation. The differences between dialects are considerable, and have led to recurrent difficulties in conceptualising a "standard Irish." In recent decades contacts between speakers of different dialects have become more frequent and the differences between the dialects are less noticeable.[84]

An Caighdeán Oifigiúil ("The Official Standard"), often shortened to An Caighdeán, is a standard for the spelling and grammar of written Irish, developed and used by the Irish government. Its rules are followed by most schools in Ireland, though schools in and near Irish-speaking regions also use the local dialect. It was published by the translation department of Dáil Éireann in 1953[85] and updated in 2012[86] and 2017.

Phonology

In pronunciation, Irish most closely resembles its nearest relatives, Scottish Gaelic and Manx. One notable feature is that consonants (except /h/) come in pairs, one "broad" (velarised, pronounced with the back of the tongue pulled back towards the soft palate) and one "slender" (palatalised, pronounced with the middle of the tongue pushed up towards the hard palate). While broad–slender pairs are not unique to Irish (being found, for example, in Russian), in Irish they have a grammatical function.

| Labial | Coronal | Dorsal | Glottal | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| broad | slender | broad | slender | broad | slender | |||

| Stop | voiceless | pˠ | pʲ | t̪ˠ | tʲ | k | c | |

| voiced | bˠ | bʲ | d̪ˠ | dʲ | ɡ | ɟ | ||

| Fricative/ Approximant |

voiceless | fˠ | fʲ | sˠ | ʃ | x | ç | h |

| voiced | w/v | vʲ | ɣ | j | ||||

| Nasal | mˠ | mʲ | n̪ˠ | nʲ | ŋ | ɲ | ||

| Tap | ɾˠ | ɾʲ | ||||||

| Lateral | l̪ˠ | lʲ | ||||||

| Front | Central | Back | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| short | long | short | short | long | |

| Close | ɪ | iː | ʊ | uː | |

| Mid | ɛ | eː | ə | ɔ | oː |

| Open | a | ɑː | |||

Diphthongs: iə, uə, əi, əu.

Syntax and morphology

Irish is a fusional, VSO, nominative-accusative language. Irish is neither verb nor satellite framed, and makes liberal use of deictic verbs.

Nouns decline for 3 numbers: singular, dual (only in conjunction with the number dhá/dá "two"), plural; 2 genders: masculine, feminine; and 4 cases: ainmneach (nomino-accusative), gairmeach (vocative), ginideach (genitive), and tabharthach (prepositional-locative), with fossilised traces of the older accusative. Adjectives agree with nouns in number, gender, and case. Adjectives generally follow nouns, though some precede or prefix nouns. Demonstrative adjectives have proximal, medial, and distal forms. The prepositional-locative case is called the dative by convention, though it originates in the Proto-Celtic ablative.

Verbs conjugate for 3 tenses: past, present, future; 2 aspects: simple, habitual; 2 numbers: singular, plural; 4 moods: indicative, subjunctive, conditional, imperative; 2 relative forms, the present and future relative; and in some verbs, independent and dependent forms. Verbs conjugate for 3 persons and an impersonal form which is actor-free; the 3rd person singular acts as a person-free personal form that can be followed or otherwise refer to any person or number.

There are two verbs for "to be", one for inherent qualities with only two forms, is "present" and ba "past" and "conditional", and one for transient qualities, with a full complement of forms except for the verbal adjective. The two verbs share the one verbal noun.

The passive voice and many other forms are periphrastic. There are a number of preverbal particles marking the negative, interrogative, subjunctive, relative clauses, etc. There is a verbal noun and verbal adjective. Verb forms are highly regular, many grammars recognise only 11 irregular verbs.

Prepositions inflect for person and number. Different prepositions govern different cases. In Old and Middle Irish, prepositions governed different cases depending on intended semantics; this has disappeared in Modern Irish except in fossilised form.

Irish had no verb to express having; instead, the word ag (at, etc.) is used in conjunction with the transient be verb bheith:

- Tá leabhar agam. "I have a book." (Literally, "there is a book at me," cf. Russian "У меня есть книга”, Finnish “minulla on kirja”, French "le livre est à moi")

- Tá leabhar agat. "You (singular) have a book."

- Tá leabhar aige. "He has a book."

- Tá leabhar aici. "She has a book."

- Tá leabhar againn. "We have a book."

- Tá leabhar agaibh. "You (plural) have a book."

- Tá leabhar acu. "They have a book."

Numerals have 3 forms: abstract, general and ordinal. The numbers from 2 to 10 (and these in combination with higher numbers) are rarely used for people, numeral nominals being used instead:

- "a dó" Two.

- "dhá leabhar" Two books.

- "beirt" Two people, a couple, "beirt fhear" Two men, "beirt bhan" Two women.

- "dara", "tarna" (free variation) Second.

Irish had both decimal and vigesimal systems:

10: a deich

20: fiche

30: vigesimal – a deich is fiche; decimal – tríocha

40: v. daichead, dá fhichead; d. ceathracha

50: v. a deich is daichead; d. caoga (also: leathchéad "half-hundred")

60: v. trí fichid; d. seasca

70: v. a deich is trí fichid; d. seachtó

80: v. cheithre fichid; d. ochtó

90: v. a deich is cheithre fichid; d. nócha

100: v. cúig fichid; d. céad

A number such as 35 has various forms:

a cúigdéag is fichid "15 and 20"

a cúig is tríocha "5 and 30"

fiche 's a cúigdéag "20 and 15"

tríocha 's a cúig "30 and 5"

The latter is most commonly used in mathematics.

Initial mutations

In Irish, there are two classes of initial consonant mutations, which express grammatical relationship and meaning in verbs, nouns and adjectives:

- Lenition (séimhiú) describes the change of stops into fricatives. Indicated in Gaelic script by a sí buailte (a dot) written above the consonant, it is shown in Latin script by adding a h.

- caith! "throw!" – chaith mé "I threw" (lenition as a past-tense marker, caused by the particle do, now generally omitted)

- gá "requirement" – easpa an ghá "lack of the requirement" (lenition marking the genitive case of a masculine noun)

- Seán "John" – a Sheáin! "John!" (lenition as part of the vocative case, the vocative lenition being triggered by a, the vocative marker before Sheáin)

- Eclipsis (urú) covers the voicing of voiceless stops, and nasalisation of voiced stops.

- Athair "Father" – ár nAthair "our Father"

- tús "start", ar dtús "at the start"

- Gaillimh "Galway" – i nGaillimh "in Galway"

Mutations are often the only way to distinguish grammatical forms. For example, the only non-contextual way to distinguish possessive pronouns "her," "his" and "their", is through initial mutations since all meanings are represented by the same word a.

- their shoe – a mbróg (eclipsis)

- his shoe – a bhróg (lenition)

- her shoe – a bróg (unchanged)

Due to initial mutation, prefixes, clitics, suffixes, root inflection, ending morphology, elision, sandhi, epenthesis, and assimilation; the beginning, core, and end of words can each change radically and even simultaneously depending on context.

Orthography

Modern Irish traditionally used the Latin alphabet without the letters j, k, q, w, x, y and z. However, some Gaelicised words use those letters: for instance, "jeep" is written as "jíp" (the letter v has been naturalised into the language, although it is not part of the traditional alphabet, and has the same pronunciation as "bh"). One diacritic sign, the acute accent (á é í ó ú), known in Irish as the síneadh fada ("long mark"; plural: sínte fada), is used in the alphabet. In idiomatic English usage, this diacritic is frequently referred to simply as the fada, where the adjective is used as a noun. The fada serves to lengthen the sound of the vowels and in some cases also changes their quality. For example, in Munster Irish (Kerry), a is /a/ or /ɑ/ and á is /ɑː/ in "father", but in Ulster Irish (Donegal), á tends to be /æː/.

Traditional orthography had an additional diacritic – a dot over some consonants to indicate lenition. In modern Irish, the letter h suffixed to a consonant indicates that the consonant is lenited. Thus, for example, 'Gaelaċ' has become 'Gaelach'. This dot-above diacritic, called a ponc séimhithe or sí buailte (often shortened to buailte), derives from the punctum delens used in medieval manuscripts to indicate deletion, similar to crossing out unwanted words in handwriting today. From this usage it was used to indicate the lenition of s (from /s/ to /h/) and f (from /f/ to zero) in Old Irish texts. Lenition of c, p, and t was indicated by placing the letter h after the affected consonant; lenition of b, d, g, or m was left unmarked. Later, both buailte and postposed h were extended to be indicators of lenition of any sound except l, n, and r, which could not be lenited. Eventually, use of the buailte predominated when texts were written using Gaelic letters, while the h predominated when writing using Roman letters.

Today, Gaelic type and the buailte are rarely used except where a "traditional" style is required, e.g. the motto on the University College Dublin coat of arms[87] or the symbol of the Irish Defence Forces, the Irish Defence Forces cap badge (Óglaiġ na h-Éireann). Letters with the buailte are available in Unicode and Latin-8 character sets (see Latin Extended Additional chart and Dot (diacritic)).[88] Postposed h has predominated due to its convenience and the lack of a character set containing the overdot before Unicode, although extending the latter method to Roman letters would theoretically have the advantage of making Irish texts significantly shorter, particularly as a large portion of the h-containing digraphs in a typical Irish text are silent (ex. the above Lughbhaidh, the old spelling of Louth, which would become Luġḃaiḋ).

Spelling reform

Around the time of the Second World War, Séamas Daltún, in charge of Rannóg an Aistriúcháin (the official translations department of the Irish government), issued his own guidelines about how to standardise Irish spelling and grammar. This de facto standard was subsequently approved by the State and called the Official Standard or Caighdeán Oifigiúil. It simplified and standardised the orthography. Many words had silent letters removed and vowel combination brought closer to the spoken language. Where multiple versions existed in different dialects for the same word, one or more were selected.

Examples:

- Gaedhealg / Gaedhilg(e) / Gaedhealaing / Gaeilic / Gaelainn / Gaoidhealg / Gaolainn → Gaeilge, "Irish language"

- Lughbhaidh → Lú, "Louth" (see County Louth Historic Names)

- biadh → bia, "food"

The standard spelling does not necessarily reflect the pronunciation used in particular dialects. For example, in standard Irish, bia, "food", has the genitive bia. In Munster Irish, however, the genitive is pronounced /bʲiːɟ/.[89] For this reason, the spelling biadh is still used by the speakers of some dialects, in particular those that show a meaningful and audible difference between biadh (nominative case) and bídh (genitive case) "of food, food's". In Munster the latter spelling regularly produces the pronunciation /bʲiːɟ/ because final -idh, -igh regularly delenites to -ig in Munster pronunciation. Another example would be the word crua, meaning "hard". This pronounced /kruəɟ/[90] in Munster, in line with the pre-Caighdeán spelling, cruaidh. In Munster, ao is pronounced /eː/ and aoi pronounced /iː/,[91] but the new spellings of saoghal, "life, world", genitive: saoghail, have become saol, genitive saoil. This produces irregularities in the match-up between the spelling and pronunciation in Munster, because the word is pronounced /sˠeːl̪ˠ/, genitive /sˠeːlʲ/.[92]

See also

- Béarlachas, Anglicisms in Irish

- Buntús Cainte, a course in basic spoken Irish

- Cumann Gaelach, Irish language Society

- Dictionary of the Irish Language

- Comparison of Scottish Gaelic and Irish

- Goidelic substrate hypothesis

- Hiberno-Latin, a variety of Medieval Latin used in Irish monasteries. It included Greek, Hebrew and Celtic neologisms.

- Irish name and Place names in Ireland

- Irish words used in the English language

- Irish, a subject of the Junior Cycle examination in Secondary schools in the Republic of Ireland

- Teastas Eorpach na Gaeilge

- List of Irish-language media

- List of artists who have released Irish-language songs

- List of English words of Irish origin

- List of Ireland-related topics

- List of Irish-language given names

- Modern literature in Irish

- Status of the Irish language

Bibliography

- Caerwyn Williams, J.E. & Ní Mhuiríosa, Máirín (ed.). Traidisiún Liteartha na nGael. An Clóchomhar Tta 1979.

- McCabe, Richard A.. Spenser's Monstrous Regiment: Elizabethan Ireland and the Poetics of Difference. Oxford University Press 2002. ISBN 0-19-818734-3.

- Hickey, Raymond. The Dialects of Irish: Study of a Changing Landscape. Walter de Gruyter, 2011. ISBN 3110238306.

- Hickey, Raymond. The Sound Structure of Modern Irish. De Gruyter Mouton 2014. ISBN 978-3-11-022659-1.

- De Brún, Pádraig. Scriptural Instruction in the Vernacular: The Irish Society and its Teachers 1818–1827. Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies 2009. ISBN 978-1-85500-212-8

- Doyle, Aidan, A History of the Irish Language: From the Norman Invasion to Independence, Oxford, 2015.

- Fitzgerald, Garrett, 'Estimates for baronies of minimal level of Irish-speaking amongst successive decennial cohorts, 117-1781 to 1861–1871,’ Volume 84, Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy 1984.

- Garvin, Tom, Preventing the Future: Why was Ireland so poor for so long?, Gill and MacMillan, 2005.

- Hindley, Reg (1991, new ed.). The Death of the Irish Language: A Qualified Obituary. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-4150-6481-1

- McMahon, Timothy G.. Grand Opportunity: The Gaelic Revival and Irish Society, 1893–1910. Syracuse University Press 2008. ISBN 978-0-8156-3158-3

- Ó Gráda, Cormac. 'Cé Fada le Fán' in Dublin Review of Books, Issue 34, 6 May 2013:[93]

- Kelly, James & Mac Murchaidh, Ciarán (eds.). Irish and English: Essays on the Linguistic and Cultural Frontier 1600–1900. Four Courts Press 2012. ISBN 978-1846823404

- Ní Mhunghaile, Lesa. 'An Eighteenth Century Irish scribe's private library: Muiris Ó Gormáin's books' in Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy, Volume 110C, 2010, pp. 239–276.

- Ní Mhuiríosa, Máirín. ‘Cumann na Scríbhneoirí: Memoir’ in Scríobh 5, ed. Seán Ó Mórdha. Baile Átha Cliath: An Clóchomhar Tta 1981.

- Ó hÓgáin, Dáithí. Labhrann Laighnigh: Téacsanna agus Cainteanna ó Shean-Chúige Laighean. Coiscéim 2011.

- Ó Laoire, Muiris. Language Use and Language Attitudes in Ireland' in Multilingualism in European Bilingual Contexts : Language Use and Attitudes, ed. David Lasagabaster and Ángel Huguet. Multilingual Matters Ltd. 2007. ISBN 1-85359-929-8

- Shibakov, Alexey. Irish Word Forms / Irische Wortformen. epubli 2017. ISBN 9783745066500

- Williams, Nicholas. 'Na Canúintí a Theacht chun Solais' in Stair na Gaeilge, ed. Kim McCone and others. Maigh Nuad 1994. ISBN 0-901519-90-1

References

- Irish at Ethnologue (22nd ed., 2019)

- Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2017). "Irish". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- Dinneen, Patrick S. (1927). Foclóir Gaedhilge agus Béarla (2d ed.). Dublin: Irish Texts Society. pp. 507 s.v. Gaedhealg. ISBN 1-870166-00-0.

- Doyle, Aidan; Gussmann, Edmund (2005). An Ghaeilge, Podręcznik Języka Irlandzkiego. pp. 423k. ISBN 83-7363-275-1.

- Dillon, Myles; Ó Cróinín, Donncha (1961). Teach Yourself Irish. p. 227. ISBN 0-340-27841-2.

- Interinstitutional Style Guide: Section 7.2.4. Rules governing the languages of the institutions European Union, 27 April 2016.

- "Gaelic: meaning in the Cambridge English Dictionary". cambridge.org. Cambridge University Press. Retrieved 22 December 2018.

- "Gaelic: Definition of Gaelic by Merriam-Webster". Merriam-Webster.com. Merriam-Webster, Incorporated.

- Ó Cadhain, Máirtín (2015). The Dirty Dust (translation of Cré na Cille [1949]). Translated by Titley, Alan. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. p. viii. ISBN 978-0-300-19849-2.

- Alan Titley European Federation of Associations and Centres of Irish Studies (EFACIS), 2015.

- De Fréine, Seán (1978). The Great Silence: The Study of a Relationship Between Language and Nationality. Irish Books & Media. ISBN 978-0-85342-516-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ó Gráda 2013.

- O'Reilly, Edward (17 March 2015). ""The unadulterated Irish language": Irish Speakers in Nineteenth Century New York". New-York Historical Society. Archived from the original on 29 July 2017. Retrieved 29 July 2017.

- See the discussion in Wolf, Nicholas M. (2014). An Irish-Speaking Island: State, Religion, Community, and the Linguistic Landscape in Ireland, 1770–1870. University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 978-0-299-30274-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- McMahon 2008, pp. 130–131.

- "The Irish language and the Church of Ireland". Church of Ireland. Archived from the original on 10 July 2017. Retrieved 29 July 2017.

- "Ireland speaks up loudly for Gaelic". The New York Times. 29 March 2005. Archived from the original on 8 January 2014. Retrieved 19 February 2017.

- Murphy, Brian (25 January 2018). "Douglas Hyde's inauguration – a signal of a new Ireland". RTÉ. Archived from the original on 7 September 2018. Retrieved 6 September 2018.

- "Douglas Hyde Opens 2RN 1 January 1926". RTÉ News. 15 February 2012. Archived from the original on 6 January 2013. Retrieved 8 May 2013.

- "Allocution en irlandais, par M. Douglas Hyde". Bibliothèque nationale de France. 28 January 1922. Retrieved 6 September 2018.

- "The Doegen Records Web Project". Archived from the original on 7 September 2018.

- "Census of Population 2016 – Profile 10 Education, Skills and the Irish Language – CSO – Central Statistics Office". Archived from the original on 12 February 2018. Retrieved 11 February 2018.

- Ó Murchú, Máirtín (1993). "Aspects of the societal status of Modern Irish". In Martin J. Ball; James Fife (eds.). The Celtic Languages. London: Routledge. pp. 471–90. ISBN 0-415-01035-7.

- "NUI Entry Requirements – Ollscoil na hÉireann – National University of Ireland". Nui.ie. Archived from the original on 5 July 2012. Retrieved 7 July 2012.

- Archived 30 November 2005 at the Wayback Machine

- "Academic claims the forced learning of Irish 'has failed'". Independent.ie. 19 January 2006.

- Regan, Mary (4 May 2010). "End compulsory Irish, says FG, as 14,000 drop subject". Irish Examiner.

- Donncha Ó hÉallaithe: "Litir oscailte chuig Enda Kenny": BEO.ie Archived 20 January 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- Siggins, Lorna (16 July 2007). "Study sees decline of Irish in Gaeltacht". The Irish Times.

- Nollaig Ó Gadhra, 'The Gaeltacht and the Future of Irish, Studies, Volume 90, Number 360

- Welsh Robert and Stewart, Bruce (1996). 'Gaeltacht,' The Oxford Companion to Irish Literature. Oxford University Press.

- Hindley, Reg (1991). The Death of the Irish Language: A Qualified Obituary. Taylor & Francis.

- Magan, Manchán (9 January 2007). "Cá Bhfuil Na Gaeilg eoirí? *". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 29 January 2017. Retrieved 17 December 2016.

- See the discussion and the conclusions reached in 'Language and Occupational Status: Linguistic Elitism in the Irish Labour Market,’ The Economic and Social Review, Vol. 40, No. 4, Winter, 2009, pp. 435–460: Ideas.repec.org Archived 29 March 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- "Constitution of Ireland". Government of Ireland. 1 July 1937. Archived from the original on 17 July 2009. Retrieved 19 June 2007.

- "Over 2.3m people using language app to learn Irish". Rte.ie. 25 November 2016. Archived from the original on 4 September 2017. Retrieved 23 September 2017.

- "Ar fheabhas! President praises volunteer Duolingo translators". Irishtimes.com. Archived from the original on 11 October 2017. Retrieved 23 September 2017.

- Siggins, Lorna (6 January 2003). "Only 25% of Gaeltacht households fluent in Irish – survey". The Irish Times. p. 5.

- Hindley 1991, Map 7: Irish speakers by towns and distinct electoral divisions, census 1926.

- "CAIN: Issues: Language: O'Reilly, C. (1997) Nationalists and the Irish Language in Northern Ireland: Competing Perspectives". Cain.ulst.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 9 October 2015. Retrieved 31 October 2015.

- GPPAC.net Archived 13 May 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- "Belfast Agreement – Full text – Section 6 (Equality) – "Economic, Social and Cultural issues"". Cain.ulst.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 22 November 2013. Retrieved 7 July 2012.

- "Irish language future is raised". BBC News. 13 December 2006. Archived from the original on 15 March 2007. Retrieved 19 June 2007.

- "We will continue to campaign until we achieve equality for the Irish language". Connemara Journal. 12 March 2014. Archived from the original on 11 October 2017. Retrieved 23 September 2017.

- "Thousands call for Irish Language Act during Belfast rally". Irishtimes.com. Archived from the original on 15 November 2017. Retrieved 15 January 2018.

- "Is í an Ghaeilge an 21ú teanga oifigiúil den Aontas Eorpach". Archived from the original on 18 March 2008. Retrieved 14 June 2008.

- "Irish to be given full official EU language status". EURACTIV.com. 10 December 2015. Archived from the original on 24 September 2017. Retrieved 23 September 2017.

- O Broin, Brian. "An Analysis of the Irish-Speaking Communities of North America: Who are they, what are their opinions, and what are their needs?". Academia. Archived from the original on 10 May 2012. Retrieved 31 March 2012. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "1. Detailed Languages Spoken at Home and Ability to Speak English for the Population 5 Years and Over for the United States: 2006–2008", Language (table), Census, 2010

- "Census 2016 Summary Results – Part 1 – CSO – Central Statistics Office". Cso.ie. Archived from the original on 30 July 2017. Retrieved 29 July 2017.

- https://www.chg.gov.ie/app/uploads/2018/07/report-of-coimisiun-na-gaeltachta.pdf

- "The Doegen Records Web Project". Archived from the original on 8 September 2018.

- Hamilton, John Noel (1974). A Phonetic Study of the Irish of Tory Island, County Donegal. Institute of Irish Studies, The Queen's University of Belfast.

- Lucas, Leslie W. (1979). Grammar of Ros Goill Irish, County Donegal. Institute of Irish Studies, The Queen's University of Belfast.

- Williams 1994, pp. 467–478.

- Borde, Andrew (1870). F.J. Furnivall (ed.). "The Fyrst Boke of the Introduction of Knowledge". N. Trubner & Co. pp. 131–135.

- "State of Ireland & Plan for its Reformation" in State Papers Ireland, Henry VIII, ii, 8.

- See Fitzgerald 1984.

- Cited in Ó Gráda 2013.

- "The Doegen Records Web Project | DHO". Dho.ie. 5 September 1928. Archived from the original on 19 March 2016. Retrieved 19 March 2016.

- See "Tony Crowley, "The Politics of Language in Ireland 1366–1922: A Sourcebook" and Leerssen, Joep, Mere Irish and Fior-Ghael: Studies in the Idea of Irish Nationality, Its Development and Literary Expression Prior to the Nineteenth Century, University of Notre Dame Press 1997, p. 51. ISBN 978-0268014278

- Ellis, Henry (ed.). The Description of Ireland, An Electronic Edition: Chapter 1 (The Names of Ireland, with the Compasse of the Same, also what Shires or Counties it Conteineth, the Diuision or Partition of the Land, and of the Language of the People): http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3atext%3a1999.03.0089

- See Ó hÓgáin 2011.

- Berresford Ellis 1975, p. 156.

- Quoted in Berresford Ellis, p. 193.

- Berresford Ellis 1975, p. 190.

- Caerwyn Williams & Uí Mhuiríosa 1979, pp. 279 and 284.

- Ní Mhunghaile 2010, pp. 239–276.

- See Fitzgerald, 1984.

- McCabe, p.31

- Quoted in Graham Kew (ed.), The Irish Sections of Fynes Moryson's unpublished itinerary (IMC, Dublin, 1998), p. 50.

- Quoted in Hardiman, James, The History of the Town and Country of the County of Galway. Dublin 1820: p. 80. https://books.google.com.au/books?id=Lv8HAAAAQAAJ&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false)

- Ó Laoire 2007, p. 164.

- Quoted in de Brún 2009, pp. 11–12.

- Fitzgerald, Garrett, ‘Estimates for baronies of minimal level of Irish-speaking amongst successive decennial cohorts, 117-1781 to 1861–1871,’ Volume 84, Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy 1984

- Ó Conluain & Ó Céileachair 1976, pp. 148–153, 163–169, 210–215.

- Uí Mhuiríosa 1981, pp. 168–181.

- "Dublin : Gaelscoileanna – Irish Medium Education". Retrieved 8 April 2020.

- Ó Broin, Brian (16 January 2010). "Schism fears for Gaeilgeoirí". The Irish Times. Archived from the original on 16 February 2018. Retrieved 16 February 2018.

- John Walsh; Bernadette OʼRourke; Hugh Rowland, Research Report on New Speakers of Irish: https://www.forasnagaeilge.ie/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/New-speakers-of-Irish-report.pdf

- Seoighe, Stiofán (22 July 2019). "Gá le doirse a oscailt do nuachainteoirí na Gaeilge: Cén chaoi gur féidir cainteoirí gníomhacha, féinmhuiníneacha a dhéanamh astu seo a fhoghlaimíonn an Ghaeilge ar scoil?". The Irish Times. Archived from the original on 22 July 2019. Retrieved 19 August 2019.

- Ní Thuathaláin, Méabh (23 July 2019). "'I'm gonna speak Irish the way that's natural for me' – craoltóir buartha faoi éilíteachas shaol na Gaeilge". Tuairisc.ie. Archived from the original on 23 July 2019. Retrieved 19 August 2019.

- "Leabharlann Teanga agus Foclóireachta". www.teanglann.ie. Retrieved 8 April 2020.

- "Irish Dialects copy of Irishlanguage.net". Archived from the original on 1 July 2016. Retrieved 31 October 2015.

- "Beginners' Blas". BBC. June 2005. Archived from the original on 3 March 2009. Retrieved 18 March 2011.

- "An Caighdeán Oifigiúil" (PDF) (in Irish). January 2012. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 April 2018. Retrieved 26 February 2018.

- UCD, "Brand Identity Guidelines" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 December 2005. Retrieved 19 April 2020. (1.8 MB). Retrieved 19 April 2020.

- Unicode 5.0, "Latin Extended Additional" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 April 2018. Retrieved 24 March 2018. (163 KB). Retrieved 13 October 2007.

- Doyle, Aidan; Gussmann, Edmund (2005). An Ghaeilge, Podręcznik Języka Irlandzkiego. p. 412. ISBN 83-7363-275-1.

- Doyle, Aidan; Gussmann, Edmund (2005). An Ghaeilge, Podręcznik Języka Irlandzkiego. p. 417. ISBN 83-7363-275-1.

- Dillon, Myles; Ó Cróinín, Donncha (1961). Teach Yourself Irish. p. 6. ISBN 0-340-27841-2.

- Doyle, Aidan; Gussmann, Edmund (2005). An Ghaeilge, Podręcznik Języka Irlandzkiego. p. 432. ISBN 83-7363-275-1.

- "CÉ FADA LE FÁN". Drb.ie. Archived from the original on 11 October 2017. Retrieved 23 September 2017.

External links

| Irish edition of Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Discover Irish

- Gaeilge ar an ghréasán Irish online resources

- 'Gael-Taca (Corcaigh)'

- "Learning Irish?," BBC

- "Social Network for learners, teachers and speakers,"

- Gaelscoil stats

- Giotaí and Top 40 Offigiúla na hÉireann programmes

- Irish Swadesh list of basic vocabulary words (from Wiktionary's Swadesh-list appendix)

- Cartlann na gCanúintí – Irish Dialect Archives

- Irish Dialect Archive Card Collection. A UCD Digital Library Collection.

- Irish Dialect Archive Manuscript Collection. A UCD Digital Library Collection.

Literature

- Extract from An Bíobla Naofa (the Bible in Irish), published by An Sagart in 1981

- Extract from the Tiomna Nua (New Testament) 1970, tr. Coslett Ó Cuinn, published by Cumann Gaelach na hEaglaise

- Extract from An Bíobla Naomhtha (The Holy Bible), 16th–17th century translation done under the supervision of William Bedell, republished in 1817 by the British and Foreign Bible Society

Grammar and pronunciation

- Learn Irish Grammar with audio and pronunciation

- An Gael Magazine – Irish Gaelic Arts, Culture, And History Alive Worldwide Today

- A short Irish and Breton phrase list with Japanese translation(Renewal) incl sound file

- Braesicke's Gramadach na Gaeilge (Engl. translation)

- Irish language in Mayo

- Die araner mundart (a phonological description of the dialect of the Aran Islands by F. N. Finck, from 1899)

- A dialect of Donegal (a phonological description of the dialect of Glenties by E. C. Quiggin, from 1906)

- Trinity College Dublin The Irish Language Synthesiser

- Cruinneog – publishers of Irish grammar checker software Anois