History of Jersey

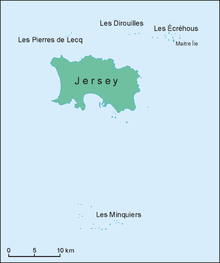

The island of Jersey and the other Channel Islands represent the last remnants of the medieval Duchy of Normandy that held sway in both France and England. Jersey lies in the Bay of Mont Saint-Michel and is the largest of the Channel Islands. It has enjoyed self-government since the division of the Duchy of Normandy in 1204.

Prehistory

The earliest evidence of human activity in Jersey dates to about 250,000 years ago (before Jersey became an island) when bands of nomadic hunters used the caves at La Cotte de St Brelade as a base for hunting mammoth and woolly rhinoceros.[1]

Rising sea levels resulted in it has been an island for approximately 6,000 years and at its current extremes it measures 10 miles east to west and six miles north to south. Evidence dating from the Ice Age period of engravings dating from at least 12,000 BC have been found,[2][3] showing occupation by Homo sapiens.

Evidence also exists of settled communities in the Neolithic period, which is marked by the building of the ritual burial sites known as dolmens. The number, size, and visible locations of these megalithic monuments (especially La Hougue Bie) have suggested that social organisation over a wide area, including surrounding coasts, was required for the construction. Archaeological evidence also shows that trading links with Brittany and the south coast of England existed during this time.

Hoards

Evidence of occupation and wealth has been discovered in the form of hoards. In 1889, during construction of a house in Saint Helier, a 746-g gold torc of Irish origin was unearthed. A Bronze Age hoard consisting of 110 implements, mostly spears and swords, was discovered in Saint Lawrence in 1976 - probably a smith's stock. Hoards of coins were discovered at La Marquanderie, in Saint Brelade, Le Câtel, in Trinity, and Le Câtillon, in Grouville (1957).[4]

In June 2012, two metal detectorists announced that they had uncovered what could be Europe's largest hoard of Iron Age Celtic coins. 70,000 late Iron Age and Roman coins. The hoard is thought to have belonged to a Curiosolitae tribe fleeing Julius Caesar's armies around 50 to 60 BC.[5][6]

In October 2012, another metal detectorist reported an earlier Bronze Age find, the Trinity Hoard.[7]

Gallo-Roman and Early Middle Ages

Although Jersey was part of the Roman world, there is a lack of evidence to give a better understanding of the island during the Gallo-Roman and early Middle Ages. The tradition that the island was called Caesarea by the Romans appears to have no basis in fact. The Roman name for the Channel Islands was I. Lenuri (Lenur Islands)[8]:4 and were occupied by the Britons during their migration to Brittany (5th-6th century).

Various saints such as the Celts Samson of Dol and Branwalator (Brelade) were active in the region. Tradition has it that Saint Helier from Tongeren in modern-day Belgium first brought Christianity to the island in the 6th century, part of the walls of the Fishermen's Chapel dates from this period and Charlemagne sent his emissary to the island (at that time called Angia, also spelt Agna)[9] in 803. A chapel built around 911, now forms part of the nave of the Parish Church of St Clement.

Normans

The island took the name Jersey as a result of Viking activity in the area between the 9th and 10th centuries. The Channel Islands remained politically linked to Brittany until 933, when William Longsword, Duke of Normandy seized the Cotentin and the islands and added them to his domain; in 1066, Duke William II of Normandy defeated Harold at Hastings to become king of England; however, he continued to rule his French possessions as a separate entity,[10] as fealty was owed as a Duke, to the King of France.

According to the Rolls of the Norman Exchequer, in 1180 Jersey was divided for administrative purposes into three ministeria:[11] de Gorroic, de Groceio and de Crapau Doit (possibly containing four parishes each).[12]:23 This was a time of building or extending churches with most parish churches in the island being built/rebuilt in a Norman style chosen by the abbey or priory to which each church had been granted. St Mary and St Martin being given to Cerisy Abbey.[12]:21

The islands remained part of the Duchy of Normandy until 1204, when King Philip II Augustus of France conquered the duchy from King John of England; thanks to Pierre de Préaux who decided to support King John, the islands remained in the personal possession of the English king[12]:25 and were described as being a Peculiar of the Crown.[13] The so-called Constitutions of King John are the foundation of modern self-government.

The Feudal Age

From 1204 onwards, the Channel Islands ceased to be a peaceful backwater and became a potential flashpoint on the international stage between England and France. In the Treaty of Paris (1259), the King of France gave up claim to the Channel Islands. The claim was based upon his position as feudal overlord of the Duke of Normandy. The King of England gave up claim to mainland Normandy and appointed a Warden, a position now termed Lieutenant Governor of Jersey and a bailiff to govern in his stead. The Channel Islands were never absorbed into the Kingdom of England. However the churches in Jersey were left under the control of the Diocese of Coutances for another 300 years.[12]:27

The existing Norman customs and laws were allowed to continue, with the exception that the ultimate head of the legal system was the King of England rather than the Duke of Normandy. There was no attempt to introduce English law. The law was conducted through 12 jurats, constables (connétable) and a bailiff (Baillé). These titles have different meanings and duties to those in England.[12]:27–8

Mont Orgueil castle was built at this time to serve as a royal fortress and military base. This was needed as the Island had few defences and had previously been suppressed by a fleet commanded by a French exile, Eustace the Monk working with the English King until in 1212 he changed sides and raided the Channel Islands on behalf of the French King.[12]:25–8 A "warden" was appointed to represent the King in the island, this title sometimes called "Captain" and later became "Governor" of the island, the duties were primarily military with the power to represent the King to appoint a bailiff who was normally an islander.[12]:32 Any oppression by a bailiff or a warden was to be resolved locally or failing that, by appeal to the King who appointed commissioners to report on disputes.

During the Hundred Years' War, the island was attacked many times[14] resulting in the formal creation of the Island Militia in 1337, which was compulsory for the next 600 years for all men of military age. In March 1338, a French force landed on Jersey, intent on capturing the island.[15] Although the island was overrun, Mont Orgueil remained in English hands.[16] The French remained until September, when they sailed off to conquer Guernsey, Alderney, and Sark. In 1339, the French returned, allegedly with 8,000 men in 17 Genoese galleys and 35 French ships. Again, they failed to take the castle and, after causing damage, withdrew.[17]

It was 1348 when the Black Death reached the Island, ravaging the population. The change in England to a written language in "English" was not taken up in Jersey, where Norman-French continued until the 20th-century.[12]:44 In July 1373, Bertrand du Guesclin overran Jersey and besieged Mont Orgueil. His troops succeeded in breaching the outer defences, forcing the garrison back to the keep. The garrison came to an agreement that they would surrender if not relieved by Michaelmas and du Guesclin sailed back to Brittany, leaving a small force to carry on the siege. An English relief fleet arrived in time.[18] On 7 October 1406, 1,000 French men at arms led by Pero Nino, a Castilian nobleman turned corsair, invaded Jersey, landing at St Aubin's Bay and defeated the 3,000 defenders but failed to capture the island.[12]:50–1

The rise of Joan of Arc inspired France to evict the English from mainland France, with the exception of Calais, putting Jersey back in the front line.[12]:54 The French did not succeed in capturing Jersey during the Hundred Years' War, but after a secret deal between Margaret of Anjou and Pierre de Brézé was made to gain French support for the Lancastrian cause during the Wars of the Roses, the French captured Mont Orgueil in the summer of 1461, and was held by the French until 1468 when Yorkist forces and local militia recaptured the castle.[19]

Due to the island's strategic importance to the English crown, the islanders were able to negotiate, over a number of centuries, the right to retain privileges and improve on certain benefits, such as trade rights, from the King.

Reformation to the civil war

During the 16th century, ideas of the reformation of the church coupled with the split with the Catholic Faith by Henry VIII of England, resulted in the islanders adopting the Protestant religion, in 1569 the churches moved under the control of the Diocese of Winchester.[12]:81 Calvinism in Jersey meant that life became very austere. Laws were strictly enforced, punishment for wrong doers was severe, but education was improved.[12]:83–6

The excommunication of Elizabeth I of England by the Pope increased the military threat to the island and the increasing use of gunpowder on the battlefield meant that the fortifications on the island had to be adapted. A new fortress was built to defend St Aubin's Bay, the new Elizabeth Castle was named after the queen by Sir Walter Raleigh when he was governor. The island militia was reorganised on a parish basis and each parish had two cannon which were usually housed in the church - one of the St Peter cannon can still be seen at the bottom of Beaumont Hill.

One of the favourable trade deals with England was the ability to import wool (England needing an export market but was at war with most of Europe).[20]:108 The production of knitwear in the island reached such a scale that it threatened the island's ability to produce its own food, so laws were passed regulating who could knit with whom and when. The name "Jersey" synonymous for a sweater, shows its importance. The islanders also became involved with the Newfoundland fisheries at this time.[21] The boats left the island in February/March following a church service in St Brelade's church and they did not return again until September/October. Colonies were established in Newfoundland.

Civil War, interregnum and restoration

During the 1640s, England, Ireland and Scotland were embroiled in the War of the Three Kingdoms. The civil war also divided Jersey, and while the sympathy of islanders lay with Parliament, the de Carterets (see Sir George Carteret and Sir Philippe de Carteret II) held the island for the king.

The Prince of Wales, the future Charles II visited the island in 1646 and again in October 1649 following the trial and execution of his father, Charles I. In the Royal Square in St. Helier on 17 February 1649, Charles was publicly proclaimed king after his father's death (following the first public proclamation in Edinburgh on 5 February 1649).[22] Parliamentarian forces eventually captured the island in 1651 and Elizabeth Castle seven weeks later. In recognition for all the help given to him during his exile, Charles II gave George Carteret, Bailiff and governor, a large grant of land in the American colonies, which he promptly named New Jersey, now part of the United States of America.[23][24]

Towards the end of the 17th century, Jersey strengthened its links with the Americas when many islanders emigrated to New England and north east Canada. The Jersey merchants built up a thriving business empire in the Newfoundland and Gaspé fisheries. Companies such as Robins and the Le Boutilliers set up thriving businesses.

18th century

By the 1720s, a discrepancy in coinage values between Jersey and France was threatening economic stability. The States of Jersey therefore resolved to devalue the liard to six to the sou. The legislation to that effect implemented in 1729 caused popular riots that shook the establishment.[25] The devaluation was therefore cancelled.

The Chamber of Commerce founded 24 February 1768 is the oldest in the Commonwealth.

The Code of 1771 laid down for the first time in one place the extant laws of Jersey, and from this time, the functions of the Royal Court and the States of Jersey were delimited, with sole legislative power vested in the States.

Methodism arrived in Jersey in 1774, brought by fishermen returning from Newfoundland. Conflict with the authorities ensued when men refused to attend militia drill when that coincided with chapel meetings. The Royal Court attempted to proscribe Methodist meetings, but King George III refused to countenance such interference with liberty of religion. The first Methodist minister in Jersey was appointed in 1783, and John Wesley preached in Jersey in August 1789, his words being interpreted into the vernacular for the benefit of those from the country parishes. The first building constructed specifically for Methodist worship was erected in St. Ouen in 1809.

The 18th century was a period of political tension between Britain and France, as the two nations clashed all over the world as their ambitions grew. Because of its position, Jersey was more or less on a continuous war footing.

During the American Wars of Independence, two attempted invasions of the island were made. In 1779, the Prince of Orange William V was prevented from landing at St Ouen's Bay; on 6 January 1781, a force led by Baron de Rullecourt captured St Helier in a daring dawn raid, but was defeated by a British army led by Major Francis Peirson in the Battle of Jersey. A short-lived peace was followed by the French Revolutionary Wars and the Napoleonic Wars which, when they had ended, had changed Jersey forever. In 1799–1800, over 6000 Russian troops under the command of Charles du Houx de Vioménil were quartered in Jersey after an evacuation of Holland.

The first printing press was introduced to Jersey in 1784.

19th century

The number of English-speaking soldiers stationed on the island and the number of retired officers and English-speaking labourers who came to the islands in the 1820s led to the island gradually moving towards an English-speaking culture in the town.

The livre tournois had been used as the legal currency for centuries. However, it was abolished during the French Revolutionary period. Although the coins were no longer minted, they remained the legal currency in Jersey until 1837, when dwindling supplies and consequent difficulties in trade and payment obliged the adoption of the pound sterling as legal tender.

The military roads constructed (on occasion at gunpoint in the face of opposition from landowners) by the governor, General George Don, to link coastal fortifications with St. Helier harbour had an unexpected effect on agriculture once peace restored reliable trade links. Farmers in previously isolated valleys were able to swiftly transport crops grown in the island's microclimate to waiting ships and then on to the markets of London and Paris ahead of the competition. In conjunction with the introduction of steamships and the development of the French and British railway systems, Jersey's agriculture was no longer as isolated as before.

The population of Jersey rose rapidly, from 47,544 in 1841 to 56,078 20 years later, despite a 20% mortality rate amongst new born children. Life expectancy was 35 years. Both immigration and emigration increased.[20]:186

The town expanded with many new streets and houses in a Georgian style, in 1843 it was agreed to erect street names. The Theatre Royal was built, as were Victoria College, Jersey in 1852 and extensions to the harbour, which were called Victoria Harbour.[20]:181–5 Jersey issued its first coins in 1841, and exhibited 34 items at The Great Exhibition in 1851, the world's first ever Pillar box was installed in 1852 and a paid police force was created in 1854.[20]:178–185

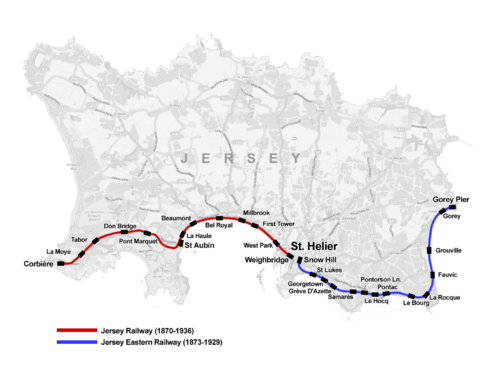

Two railways, the Jersey Western Railway[26] in 1870, and the Jersey Eastern Railway[27] in 1874, were opened. The western railway from St Helier (Weighbridge) to La Corbière and the eastern railway from St Helier (Snow Hill) to Gorey Pier. The two railways have never been connected. Buses started running on the island in the 1920s, and the railways could not cope with the competition. The eastern railway closed in 1926 and the western railway in 1936 after a fire disaster that year.

Jersey was the fourth-largest shipbuilding area in the 19th-century British Isles,[28] building over 900 vessels around the island. Shipbuilding declined with the coming of iron ships and steam. A number of banks on Jersey, guarantors of an industry both onshore and off, failed in 1873[20]:193 and 1886, even causing strife and discord in far-flung societies. The population fell slightly in the 20 years to 1881.

In the late 19th century, as the former thriving cider and wool industries declined, island farmers benefited from the development of two luxury products - Jersey cattle and Jersey Royal potatoes. The former was the product of careful and selective breeding programmes; the latter was a total fluke.

The anarchist philosopher, Peter Kropotkin, who visited the Channel Islands in 1890, 1896, and 1903, described the agriculture of Jersey in The Conquest of Bread.

The 19th century also saw the rise of tourism as an important industry (linked with the improvement in passenger ships)[20]:196 which reached its climax in the period from the end of the Second World War to the 1980s.

20th century

Elementary education became obligatory in 1899, and free in 1907. The years before the First World War saw the foundation of cultural institutions, the Battle of Flowers and the Jersey Eisteddfod. The first aeroplanes arrived in Jersey in 1912.

In 1914, the British garrison was withdrawn at the start of the war and the militia were mobilised. Jersey men served in the British and French armed forces. Numbers of German prisoners of war were interned in Jersey. The influenza epidemic of 1918 added to the toll of war.

In 1919, imperial measurements replaced, for the most part, the tradition Jersey system of weights and measures; women aged over 30 were given the vote;[29] and the endowments of the ancient grammar schools were repurposed as scholarships for Victoria College.

In 1921, the visit of King George V was the occasion for the design of the parish crests.

In 1923, the British government asked Jersey to contribute an annual sum towards the costs of the Empire. The States of Jersey refused and offered instead a one-off contribution to war costs. After negotiations, Jersey's one-off contribution was accepted.

The first motor car had arrived in 1899, and by the 1930s, competition from motor buses had rendered the railways unprofitable, with final closure coming in 1935 (except for the later German reintroduction of rail during the military occupation). Jersey Airport was opened in 1937 to replace the use of the beach of Saint Aubin's bay as an airstrip at low tide.[4]

English was first permitted in debates in the States of Jersey in 1901, and the first legislation to be drawn up primarily in English was the Income Tax Law of 1928.

Occupation 1940-1945

Following the withdrawal of defences by the British government and German bombardment, Jersey was occupied by German troops between 1940 and 1945.[30] The Channel Islands were the only British soil occupied by German troops in World War II. This period of occupation had about 8,000 islanders evacuated, 1,200 islanders deported to camps in Germany, and over 300 islanders sentenced to the prison and concentration camps of mainland Europe. Twenty died as a result. The islanders endured near-starvation in the winter of 1944–45, after the Channel Islands had been cut off from German-occupied Europe by Allied forces advancing from the Normandy beachheads, avoided only by the arrival of the Red Cross supply ship Vega in December 1944. Liberation Day - 9 May is marked as a public holiday.

Post-Liberation growth

The event which has had the most far-reaching effect on Jersey in modern times is the growth of the finance industry in the island from the 1960s onwards. With the release of the Paradise Papers, it was learned that two non-U.S. subsidiaries of Apple were domiciled in Jersey for one year (2015).[31]

See also

References

- Cunliffe, Barry (1994). The Oxford Illustrated Prehistory of Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0198143850.

- "Ice Age engravings found at Jersey archaeological site". BBC. 2 November 2015.

- "Over 3,000 stone tools have been found here". Jersey heritage.

- Balleine's History of Jersey, Marguerite Syvret and Joan Stevens (1998) ISBN 1-86077-065-7

- Morrison, Ryan (2012-09-13). "BBC News - Jersey coin hoard left by Celtic tribe in flight from Caesar army". Bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 2012-10-11.

- "Celtic Tribe Fleeing Caesar Army Left Behind Thousands of Coins Reports CustomCoinStore.com | Oct 2, 2012". Sbwire.com. 2012-10-02. Archived from the original on 2013-11-02. Retrieved 2013-10-31.

- "BBC News - Bronze age pottery find in Jersey". Bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 2012-10-11.

- Rule, Margaret. A Gallo-Roman Trading Vessel from Guernsey. Guernsey Museums & Galleries. ISBN 978-1871560039.

- "History of stamps". Jersey Post. Archived from the original on 2006-10-22. Retrieved 2006-10-24.

- "A Short Constitutional History of Jersey". Voisin & Co. 1999-05-18. Archived from the original on 2010-12-06. Retrieved 2009-06-25.

- Stapleton, Thomas (1840). Magni rotuli scaccarii Normanniæ sub regibus Angliæ.

- Syvret, Marguerite (2011). Balleine’s History of Jersey. The History Press. ISBN 978-1860776502.

- Liddicoat, Anthony (1 August 1994). A Grammar of the Norman French of the Channel Islands. Walter de Gruyter. p. 6. ISBN 3-11-012631-1.

- Including twice in the 1338-39 Channel campaign

- Watts (2007), pp. 8-17

- Ford (2004), pp. 18–25

- Ford (2004), p. 22

- Ford (2004), p. 23

- Watts (2004), pp. 16–17

- Lempriére, Raoul. History of the Channel Islands. Robert Hale Ltd. ISBN 978-0709142522.

- Ommer, Rosemary E. (1991). From Outpost to Outport. McGill-Queen's University Press. pp. 13–14. ISBN 0-7735-0730-2.

- Jansso, Maija. Art and Diplomacy: Seventeenth-Century English Decorated Royal Letters to Russia and the Far East. BRILL, 2015. p. 204. ISBN 9789004300453.

- Weeks, Daniel J. (1 May 2001). Not for Filthy Lucre's Sake. Lehigh University Press. p. 45. ISBN 0-934223-66-1.

- Cochrane, Willard W. (30 September 1993). The Development of American Agriculture. University of Minnesota Press. p. 18. ISBN 0-8166-2283-3.

-

- Balleine's History of Jersey, Marguerite Syvret and Joan Stevens (1998) ISBN 1-86077-065-7

- "Jersey Western Railway - theislandwiki". www.theislandwiki.org. Retrieved 24 February 2018.

- "Jersey Eastern Railway - theislandwiki". www.theislandwiki.org. Retrieved 24 February 2018.

- "Tourism schooner plans unveiled". 24 December 2003. Retrieved 24 February 2018 – via news.bbc.co.uk.

- Heritage, Jersey (2018-01-31). "What's Her Street's Story?". JerseyHeritage.org. Retrieved 2019-05-14.

- Bellows, Tony. "What was the "Occupation" and why is "Liberation Day" celebrated in the Channel Islands?". Société Jersiaise. Archived from the original on 2007-04-03. Retrieved 2006-10-24.

- "Paradise Papers: Apple's secret tax bolthole revealed". BBC.com. Retrieved 6 November 2017.

Print

- Balleine's History of Jersey, Marguerite Syvret and Joan Stevens (1998) ISBN 1-86077-065-7