History of the Netherlands

The History of the Netherlands is a history of seafaring people thriving on a lowland river delta on the North Sea in northwestern Europe. Records begin with the four centuries during which the region formed a militarized border zone of the Roman Empire. This came under increasing pressure from Germanic peoples moving westwards. As Roman power collapsed and the Middle Ages began, three dominant Germanic peoples coalesced in the area, Frisians in the north and coastal areas, Low Saxons in the northeast, and the Franks in the south.

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of the Netherlands |

|

|

Early

|

|

Republic |

|

Topics

|

|

|

During the Middle Ages, the descendants of the Carolingian dynasty came to dominate the area and then extended their rule to a large part of Western Europe. The region nowadays corresponding to the Netherlands therefore became part of Lower Lotharingia within the Frankish Holy Roman Empire. For several centuries, lordships such as Brabant, Holland, Zeeland, Friesland, Guelders and others held a changing patchwork of territories. There was no unified equivalent of the modern Netherlands.

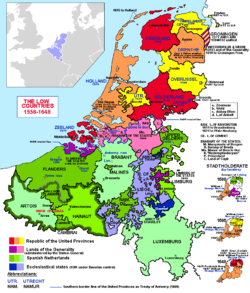

By 1433, the Duke of Burgundy had assumed control over most of the lowlands territories in Lower Lotharingia; he created the Burgundian Netherlands which included modern Netherlands, Belgium, Luxembourg, and a part of France.

The Catholic kings of Spain took strong measures against Protestantism, which polarised the peoples of present-day Belgium and the Netherlands. The subsequent Dutch revolt led to the splitting in 1581 of the Burgundian Netherlands into a Catholic, French- and Dutch-speaking "Spanish Netherlands" (approximately corresponding to modern Belgium and Luxembourg), and a northern "United Provinces" (or "Dutch Republic)", which spoke Dutch and was predominantly Protestant. The latter entity became the modern Netherlands.

In the Dutch Golden Age, which had its zenith around 1667, there was a flowering of trade, industry, and the sciences. A rich worldwide Dutch empire developed and the Dutch East India Company became one of the earliest and most important of national mercantile companies based on entrepreneurship and trade.

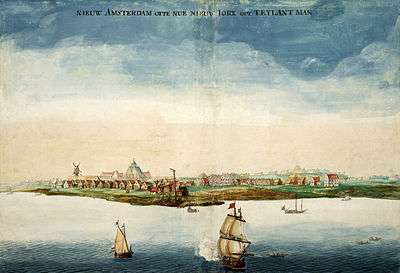

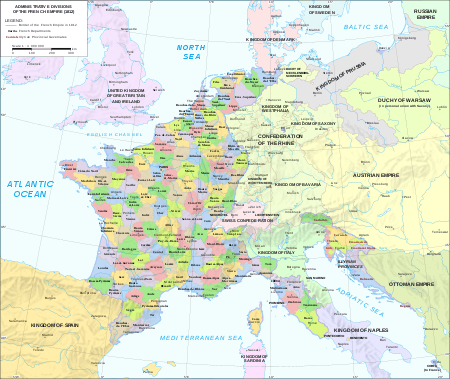

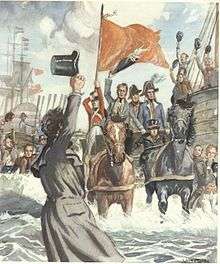

During the eighteenth century, the power, wealth and influence of the Netherlands declined. A series of wars with the more powerful British and French neighbours weakened it. The UK seized the North American colony of New Amsterdam, and renamed it "New York". There was growing unrest and conflict between the Orangists and the Patriots. The French Revolution spilled over after 1789, and a pro-French Batavian Republic was established in 1795–1806. Napoleon made it a satellite state, the Kingdom of Holland (1806–1810), and later simply a French imperial province.

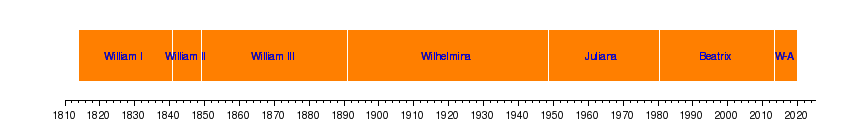

After the collapse of Napoleon in 1813–15, an expanded "United Kingdom of the Netherlands" was created with the House of Orange as monarchs, also ruling Belgium and Luxembourg. The King imposed unpopular Protestant reforms on Belgium, which revolted in 1830 and became independent in 1839. After an initially conservative period, following the introduction of the 1848 constitution; the country became a parliamentary democracy with a constitutional monarch. Modern-day Luxembourg became officially independent from the Netherlands in 1839, but a personal union remained until 1890. Since 1890, it is ruled by another branch of the House of Nassau.

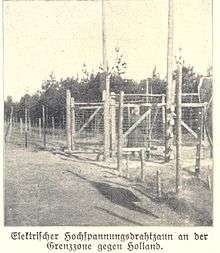

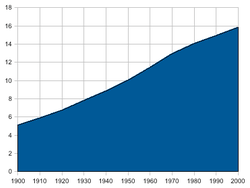

The Netherlands was neutral during the First World War, but during the Second World War, it was invaded and occupied by Nazi Germany. The Nazis, including many collaborators, rounded up and killed almost all of the country's Jewish population. When the Dutch resistance increased, the Nazis cut off food supplies to much of the country, causing severe starvation in 1944–45. In 1942, the Dutch East Indies were conquered by Japan, but prior to this the Dutch destroyed the oil wells for which Japan was desperate. Indonesia proclaimed its independence from the Netherlands in 1945, followed by Suriname in 1975. The post-war years saw rapid economic recovery (helped by the American Marshall Plan), followed by the introduction of a welfare state during an era of peace and prosperity. The Netherlands formed a new economic alliance with Belgium and Luxembourg, the Benelux, and all three became founding members of the European Union and NATO. In recent decades, the Dutch economy has been closely linked to that of Germany and is highly prosperous. The four countries adopted the Euro on 1 January 2002, along with eight other EU member states.

Prehistory (before 800 BC)

Historical changes to the landscape

The prehistory of the area that is now the Netherlands was largely shaped by its constantly shifting, low-lying geography.

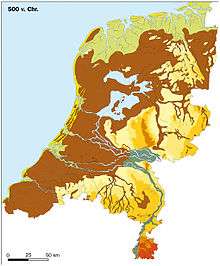

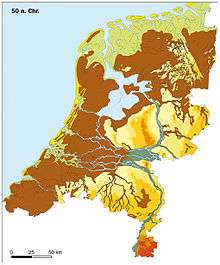

The Netherlands in 5500 BC |

The Netherlands in 3850 BC |

The Netherlands in 2750 BC |

The Netherlands in 500 BC |

The Netherlands in AD 50 |

beach ridges and dunes

peat marshes and floodplain silt areas

(including old river courses and riverbank breaches which have filled up with silt or peat) Valleys of the major rivers (not covered with peat)

open water (sea, lagoons, rivers)

Pleistocene landscape (> −6 m compared to NAP)

Pleistocene landscape (−6 to 0 m; –20 to 0 ft)

Pleistocene landscape (0–10 m; 0–33 ft)

Pleistocene landscape (10–20 m; 33–66 ft)

Pleistocene landscape (20–50 m; 66–164 ft)

Pleistocene landscape (50–100 m; 164–328 ft)

Pleistocene landscape (100–200 m; 328–656 ft) |

Earliest groups of hunter-gatherers (before 5000 BC)

The area that is now the Netherlands was inhabited by early humans at least 37,000 years ago, as attested by flint tools discovered in Woerden in 2010.[1] In 2009 a fragment of a 40,000-year-old Neanderthal skull was found in sand dredged from the North Sea floor off the coast of Zeeland.[2]

During the last ice age, the Netherlands had a tundra climate with scarce vegetation and the inhabitants survived as hunter-gatherers. After the end of the ice age, various Paleolithic groups inhabited the area. It is known that around 8000 BC a Mesolithic tribe resided near Burgumer Mar (Friesland). Another group residing elsewhere is known to have made canoes. The oldest recovered canoe in the world is the Pesse canoe.[3][4] According to C14 dating analysis it was constructed somewhere between 8200 BC and 7600 BC.[4] This canoe is exhibited in the Drents Museum in Assen.

Autochthonous hunter-gatherers from the Swifterbant culture are attested from around 5600 BC onwards.[5] They are strongly linked to rivers and open water and were related to the southern Scandinavian Ertebølle culture (5300–4000 BC). To the west, the same tribes might have built hunting camps to hunt winter game, including seals.

The arrival of farming (around 5000–4000 BC)

Agriculture arrived in the Netherlands somewhere around 5000 BC with the Linear Pottery culture, who were probably central European farmers. Agriculture was practiced only on the loess plateau in the very south (southern Limburg), but even there it was not established permanently. Farms did not develop in the rest of the Netherlands.

There is also some evidence of small settlements in the rest of the country. These people made the switch to animal husbandry sometime between 4800 BC and 4500 BC. Dutch archaeologist Leendert Louwe Kooijmans wrote, "It is becoming increasingly clear that the agricultural transformation of prehistoric communities was a purely indigenous process that took place very gradually."[5] This transformation took place as early as 4300 BC–4000 BC[6] and featured the introduction of grains in small quantities into a traditional broad-spectrum economy.[7]

Funnelbeaker and other cultures (around 4000–3000 BC)

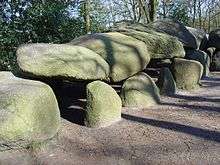

The Funnelbeaker culture was a farming culture extending from Denmark through northern Germany into the northern Netherlands. In this period of Dutch prehistory, the first notable remains were erected: the dolmens, large stone grave monuments. They are found in Drenthe, and were probably built between 4100 BC and 3200 BC.

To the west, the Vlaardingen culture (around 2600 BC), an apparently more primitive culture of hunter-gatherers survived well into the Neolithic period.

Corded Ware and Bell Beaker cultures (around 3000–2000 BC)

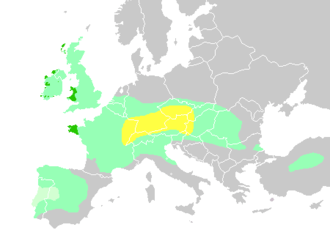

Around 2950 BCE there was a transition from the Funnelbeaker farming culture to the Corded Ware pastoralist culture, a large archeological horizon appearing in western and central Europe, that is associated with the advance of Indo-European languages. This transition was probably caused by developments in eastern Germany, and it occurred within two generations.[8]

The Bell Beaker culture was also present in the Netherlands.[9][10]

The Corded Ware and Bell Beaker cultures were not indigenous to the Netherlands but were pan-European in nature, extending across much of northern and central Europe.

The first evidence of the use of the wheel dates from this period, about 2400 BC. This culture also experimented with working with copper. Evidence of this, including stone anvils, copper knives, and a copper spearhead, was found on the Veluwe. Copper finds show that there was trade with other areas in Europe, as natural copper is not found in Dutch soil.

Bronze Age (around 2000–800 BC)

The Bronze Age probably started somewhere around 2000 BC and lasted until around 800 BC. The earliest bronze tools have been found in the grave of a Bronze Age individual called "the smith of Wageningen". More Bronze Age objects from later periods have been found in Epe, Drouwen and elsewhere. Broken bronze objects found in Voorschoten were apparently destined for recycling. This indicates how valuable bronze was considered in the Bronze Age. Typical bronze objects from this period included knives, swords, axes, fibulae and bracelets.

Most of the Bronze Age objects found in the Netherlands have been found in Drenthe. One item shows that trading networks during this period extended a far distance. Large bronze situlae (buckets) found in Drenthe were manufactured somewhere in eastern France or in Switzerland. They were used for mixing wine with water (a Roman/Greek custom). The many finds in Drenthe of rare and valuable objects, such as tin-bead necklaces, suggest that Drenthe was a trading centre in the Netherlands in the Bronze Age.

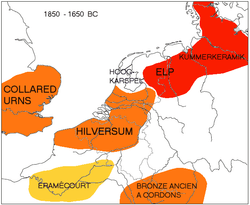

The Bell Beaker cultures (2700–2100) locally developed into the Bronze Age Barbed-Wire Beaker culture (2100–1800). In the second millennium BC, the region was the boundary between the Atlantic and Nordic horizons and was split into a northern and a southern region, roughly divided by the course of the Rhine.

In the north, the Elp culture (c. 1800 to 800 BC)[11] was a Bronze Age archaeological culture having earthenware pottery of low quality known as "Kümmerkeramik" (or "Grobkeramik") as a marker. The initial phase was characterized by tumuli (1800–1200 BC) that were strongly tied to contemporary tumuli in northern Germany and Scandinavia, and were apparently related to the Tumulus culture (1600–1200 BC) in central Europe. This phase was followed by a subsequent change featuring Urnfield (cremation) burial customs (1200–800 BC). The southern region became dominated by the Hilversum culture (1800–800), which apparently inherited the cultural ties with Britain of the previous Barbed-Wire Beaker culture.

The pre-Roman period (800 BC – 58 BC)

Iron Age

The Iron Age brought a measure of prosperity to the people living in the area of the present-day Netherlands. Iron ore was available throughout the country, including bog iron extracted from the ore in peat bogs (moeras ijzererts) in the north, the natural iron-bearing balls found in the Veluwe and the red iron ore near the rivers in Brabant. Smiths travelled from small settlement to settlement with bronze and iron, fabricating tools on demand, including axes, knives, pins, arrowheads and swords. Some evidence even suggests the making of Damascus steel swords using an advanced method of forging that combined the flexibility of iron with the strength of steel.

In Oss, a grave dating from around 500 BC was found in a burial mound 52 metres wide (and thus the largest of its kind in western Europe). Dubbed the "king's grave" (Vorstengraf (Oss)), it contained extraordinary objects, including an iron sword with an inlay of gold and coral.

In the centuries just before the arrival of the Romans, northern areas formerly occupied by the Elp culture emerged as the probably Germanic Harpstedt culture[12] while the southern parts were influenced by the Hallstatt culture and assimilated into the Celtic La Tène culture. The contemporary southern and western migration of Germanic groups and the northern expansion of the Hallstatt culture drew these peoples into each other's sphere of influence.[13] This is consistent with Caesar's account of the Rhine forming the boundary between Celtic and Germanic tribes.

Arrival of Germanic groups

.png)

The Germanic tribes originally inhabited southern Scandinavia, Schleswig-Holstein and Hamburg,[14] but subsequent Iron Age cultures of the same region, like Wessenstedt (800–600 BC) and Jastorf, may also have belonged to this grouping.[15] The climate deteriorating in Scandinavia around 850 BC to 760 BC and later and faster around 650 BC might have triggered migrations. Archaeological evidence suggests around 750 BC a relatively uniform Germanic people from the Netherlands to the Vistula and southern Scandinavia.[14] In the west, the newcomers settled the coastal floodplains for the first time, since in adjacent higher grounds the population had increased and the soil had become exhausted.[16]

By the time this migration was complete, around 250 BC, a few general cultural and linguistic groupings had emerged.[17][18]

One grouping – labelled the "North Sea Germanic" – inhabited the northern part of the Netherlands (north of the great rivers) and extending along the North Sea and into Jutland. This group is also sometimes referred to as the "Ingvaeones". Included in this group are the peoples who would later develop into, among others, the early Frisians and the early Saxons.[18]

A second grouping, which scholars subsequently dubbed the "Weser-Rhine Germanic" (or "Rhine-Weser Germanic"), extended along the middle Rhine and Weser and inhabited the southern part of the Netherlands (south of the great rivers). This group, also sometimes referred to as the "Istvaeones", consisted of tribes that would eventually develop into the Salian Franks.[18]

Celts in the south

The Celtic culture had its origins in the central European Hallstatt culture (c. 800–450 BC), named for the rich grave finds in Hallstatt, Austria.[19] By the later La Tène period (c. 450 BC up to the Roman conquest), this Celtic culture had, whether by diffusion or migration, expanded over a wide range, including into the southern area of the Netherlands. This would have been the northern reach of the Gauls.

In March 2005 17 Celtic coins were found in Echt (Limburg). The silver coins, mixed with copper and gold, date from around 50 BC to 20 AD. In October 2008 a hoard of 39 gold coins and 70 silver Celtic coins was found in the Amby area of Maastricht.[20] The gold coins were attributed to the Eburones people.[21] Celtic objects have also been found in the area of Zutphen.[22]

Although it is rare for hoards to be found, in past decades loose Celtic coins and other objects have been found throughout the central, eastern and southern part of the Netherlands. According to archaeologists these finds confirmed that at least the Maas river valley in the Netherlands was within the influence of the La Tène culture. Dutch archaeologists even speculate that Zutphen (which lies in the centre of the country) was a Celtic area before the Romans arrived, not a Germanic one at all.[22]

Scholars debate the actual extent of the Celtic influence.[16][23] The Celtic influence and contacts between Gaulish and early Germanic culture along the Rhine is assumed to be the source of a number of Celtic loanwords in Proto-Germanic. But according to Belgian linguist Luc van Durme, toponymic evidence of a former Celtic presence in the Low Countries is near to utterly absent.[24] Although there were Celts in the Netherlands, Iron Age innovations did not involve substantial Celtic intrusions and featured a local development from Bronze Age culture.[16]

The Nordwestblock theory

Some scholars (De Laet, Gysseling, Hachmann, Kossack & Kuhn) have speculated that a separate ethnic identity, neither Germanic nor Celtic, survived in the Netherlands until the Roman period. They see the Netherlands as having been part of an Iron Age "Nordwestblock" stretching from the Somme to the Weser.[25][26] Their view is that this culture, which had its own language, was being absorbed by the Celts to the south and the Germanic peoples from the east as late as the immediate pre-Roman period.

Roman era (57 BC – 410 AD)

Native tribes

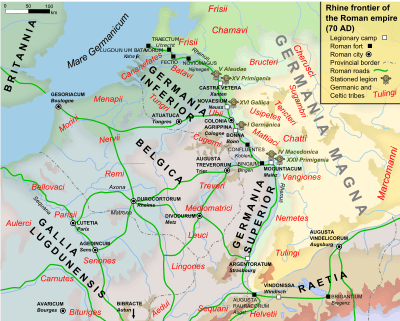

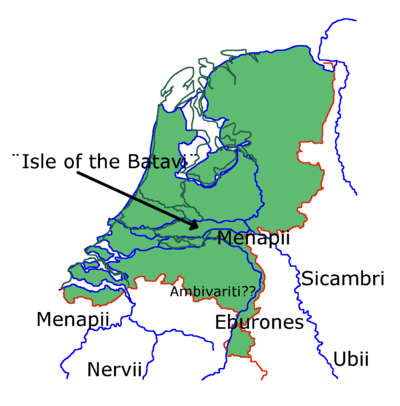

During the Gallic Wars, the Belgic area south of the Oude Rijn and west of the Rhine was conquered by Roman forces under Julius Caesar in a series of campaigns from 57 BC to 53 BC.[26] The tribes located in the area of the Netherlands at this time did not leave behind written records, so all the information known about them during this pre-Roman period is based on what the Romans and Greeks wrote about them. One of the most important is Caesar's own Commentarii de Bello Gallico. Two main tribes he described as living in what is now the Netherlands were the Menapii, and the Eburones, both in the south, which is where Caesar was active. He established the principle that the Rhine defined a natural boundary between Gaul and Germania magna. But the Rhine was not a strong border, and he made it clear that there was a part of Belgic Gaul where many of the local tribes (including the Eburones) were "Germani cisrhenani", or in other cases, of mixed origin.

The Menapii stretched from the south of Zeeland, through North Brabant (and possibly South Holland), into the southeast of Gelderland. In later Roman times their territory seems to have been divided or reduced, so that it became mainly contained in what is now western Belgium.

The Eburones, the largest of the Germani Cisrhenani group, covered a large area including at least part of modern Dutch Limburg, stretching east to the Rhine in Germany, and also northwest to the delta, giving them a border with the Menapii. Their territory may have stretched into Gelderland.

In the delta itself, Caesar makes a passing comment about the Insula Batavorum ("Island of the Batavi") in the Rhine river, without discussing who lived there. Later, in imperial times, a tribe called the Batavi became very important in this region.[27] Much later Tacitus wrote that they had originally been a tribe of the Chatti, a tribe in Germany never mentioned by Caesar.[28] However, archaeologists find evidence of continuity, and suggest that the Chattic group may have been a small group, moving into a pre-existing (and possibly non-Germanic) people, who could even have been part of a known group such as the Eburones.[29]

Tribes named by Julius Caesar.

Tribes named by Julius Caesar. Tribes during Roman Empire.

Tribes during Roman Empire.

The approximately 450 years of Roman rule that followed would profoundly change the area that would become the Netherlands. Very often this involved large-scale conflict with the free Germanic tribes over the Rhine.

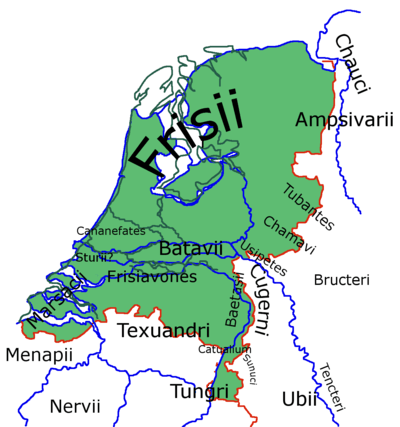

Other tribes who eventually inhabited the islands in the delta during Roman times are mentioned by Pliny the Elder are the Cananefates in South Holland; the Frisii, covering most of the modern Netherlands north of the Oude Rijn; the Frisiabones, who apparently stretched from the delta into the North of North Brabant; the Marsacii, who stretched from the Flemish coast, into the delta; and the Sturii.[30]

Caesar reported that he eliminated the name of the Eburones but in their place the Texuandri inhabited most of North Brabant, and the modern province of Limburg, with the Maas running through it, appears to have been inhabited in imperial times by (from north to south) the Baetasii, the Catualini, the Sunuci and the Tungri. (Tacitus reported that the Tungri was a new name for the earlier Germani cisrhenani.)

North of the Old Rhine, apart from the Frisii, Pliny reports some Chauci reached into the delta, and two other tribes known from the eastern Netherlands were the Tuihanti (or Tubantes) from Twenthe in Overijssel, and the Chamavi, from Hamaland in northern Gelderland, who became one of the first tribes to be named as Frankish (see below). The Salians, also Franks, probably originated in Salland in Overijssel, before they moved into the empire, forced by Saxons in the 4th century, first into Batavia, and then into Toxandria.

Roman settlements in the Netherlands

Starting about 15 BC, the Rhine, in the Netherlands came to be defended by the Lower Limes Germanicus. After a series of military actions, the Rhine became fixed around 12 AD as Rome's northern frontier on the European mainland. A number of towns and developments would arise along this line. The area to the south would be integrated into the Roman Empire. At first part of Gallia Belgica, this area became part of the province of Germania Inferior. The tribes already within, or relocated to, this area became part of the Roman Empire. The area to the north of the Rhine, inhabited by the Frisii and the Chauci, remained outside Roman rule but not its presence and control.

Romans built military forts along the Limes Germanicus and a number of towns and smaller settlements in the Netherlands. The more notable Roman towns were at Nijmegen (Ulpia Noviomagus Batavorum) and at Voorburg (Forum Hadriani).

Perhaps the most evocative Roman ruin is the mysterious Brittenburg, which emerged from the sand at the beach in Katwijk several centuries ago, only to be buried again. These ruins were part of Lugdunum Batavorum.

Other Roman settlements, fortifications, temples and other structures have been found at Alphen aan de Rijn (Albaniana); Bodegraven; Cuijk; Elst, Overbetuwe; Ermelo; Esch; Heerlen; Houten; Kessel, North Brabant; Oss, i.e. De Lithse Ham near Maren-Kessel; Kesteren in Neder-Betuwe; Leiden (Matilo); Maastricht; Meinerswijk (now part of Arnhem); Tiel; Utrecht (Traiectum); Valkenburg (South Holland) (Praetorium Agrippinae); Vechten (Fectio) now part of Bunnik; Velsen; Vleuten; Wijk bij Duurstede (Levefanum); Woerden (Laurium or Laurum); and Zwammerdam (Nigrum Pullum).

Batavian revolt

The Batavians, Cananefates, and the other border tribes were held in high regard as soldiers throughout the empire, and traditionally served in the Roman cavalry.[31] The frontier culture was influenced by the Romans, Germanic people, and Gauls. In the first centuries after Rome's conquest of Gaul, trade flourished. And Roman, Gaulish and Germanic material culture are found combined in the region.

However, the Batavians rose against the Romans in the Batavian rebellion of 69 AD. The leader of this revolt was Batavian Gaius Julius Civilis. One of the causes of the rebellion was that the Romans had taken young Batavians as slaves. A number of Roman castella were attacked and burnt. Other Roman soldiers in Xanten and elsewhere and auxiliary troops of Batavians and Canninefatae in the legions of Vitellius) joined the revolt, thus splitting the northern part of the Roman army. In April 70 AD, a few legions sent by Vespasianus and commanded by Quintus Petillius Cerialis eventually defeated the Batavians and negotiated surrender with Gaius Julius Civilis somewhere between the Waal and the Maas near Noviomagus (Nijmegen), which was probably called "Batavodurum" by the Batavians.[32] The Batavians later merged with other tribes and became part of the Salian Franks.

Dutch writers in the 17th and 18th centuries saw the rebellion of the independent and freedom-loving Batavians as mirroring the Dutch revolt against Spain and other forms of tyranny. According to this nationalist view, the Batavians were the "true" forefathers of the Dutch, which explains the recurring use of the name over the centuries. Jakarta was named "Batavia" by the Dutch in 1619. The Dutch republic created in 1795 on the basis of French revolutionary principles was called the Batavian Republic. Even today Batavian is a term sometimes used to describe the Dutch people; this is similar to use of Gallic to describe the French and Teutonic to describe the Germans.[33]

Emergence of the Franks

Modern scholars of the Migration Period are in agreement that the Frankish identity emerged at the first half of the 3rd century out of various earlier, smaller Germanic groups, including the Salii, Sicambri, Chamavi, Bructeri, Chatti, Chattuarii, Ampsivarii, Tencteri, Ubii, Batavi and the Tungri, who inhabited the lower and middle Rhine valley between the Zuyder Zee and the river Lahn and extended eastwards as far as the Weser, but were the most densely settled around the IJssel and between the Lippe and the Sieg. The Frankish confederation probably began to coalesce in the 210s.[34]

The Franks eventually were divided into two groups: the Ripuarian Franks (Latin: Ripuari), who were the Franks that lived along the middle-Rhine River during the Roman Era, and the Salian Franks, who were the Franks that originated in the area of the Netherlands.

Franks appear in Roman texts as both allies and enemies (laeti and dediticii). By about 320, the Franks had the region of the Scheldt river (present day west Flanders and southwest Netherlands) under control, and were raiding the Channel, disrupting transportation to Britain. Roman forces pacified the region, but did not expel the Franks, who continued to be feared as pirates along the shores at least until the time of Julian the Apostate (358), when Salian Franks were allowed to settle as foederati in Toxandria, according to Ammianus Marcellinus.[34]

Disappearance of the Frisii?

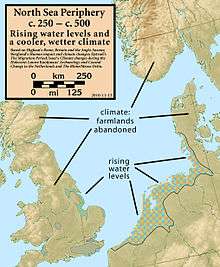

Three factors contributed to the probable disappearance of the Frisii from the northern Netherlands. First, according to the Panegyrici Latini (Manuscript VIII), the ancient Frisii were forced to resettle within Roman territory as laeti (i.e., Roman-era serfs) in c. 296.[35] This is the last reference to the ancient Frisii in the historical record. What happened to them, however, is suggested in the archaeological record. The discovery of a type of earthenware unique to 4th-century Frisia, called terp Tritzum, shows that an unknown number of them were resettled in Flanders and Kent,[36] likely as laeti under Roman coercion. Second, the environment in the low-lying coastal regions of northwestern Europe began to lower c. 250 and gradually receded over the next 200 years. Tectonic subsidence, a rising water table and storm surges combined to flood some areas with marine transgressions. This was accelerated by a shift to a cooler, wetter climate in the region. Any Frisii left in the lower area's of Frisia, would have drowned.[37][38][39][40] Third, after the collapse of the Roman Empire, there was a decline in population as Roman activity stopped and Roman institutions withdrew. As a result of these three factors, it has been postulated that the Frisii and Frisiaevones disappeared from the area, leaving the coastal lands largely unpopulated for the next two centuries.[37][38][39][40] However, recent excavations in the coastal dunes of Kennemerland show clear indication of a permanent habitation.[41][42]

Early Middle Ages (411–1000)

Frisians

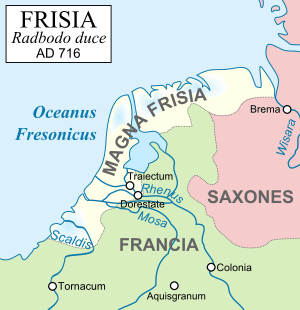

As climatic conditions improved, there was another mass migration of Germanic peoples into the area from the east. This is known as the "Migration Period" (Volksverhuizingen). The northern Netherlands received an influx of new migrants and settlers, mostly Saxons, but also Angles and Jutes. Many of these migrants did not stay in the northern Netherlands but moved on to England and are known today as the Anglo-Saxons. The newcomers who stayed in the northern Netherlands would eventually be referred to as "Frisians", although they were not descended from the ancient Frisii. These new Frisians settled in the northern Netherlands and would become the ancestors of the modern Frisians.[43][44] (Because the early Frisians and Anglo-Saxons were formed from largely identical tribal confederacies, their respective languages were very similar. Old Frisian is the most closely related language to Old English[45] and the modern Frisian dialects are in turn the closest related languages to contemporary English.) By the end of the 6th century, the Frisian territory in the northern Netherlands had expanded west to the North Sea coast and, by the 7th century, south to Dorestad. During this period most of the northern Netherlands was known as Frisia. This extended Frisian territory is sometimes referred to as Frisia Magna (or Greater Frisia).

In the 7th and 8th centuries, the Frankish chronologies mention this area as the kingdom of the Frisians. This kingdom comprised the coastal provinces of the Netherlands and the German North Sea coast. During this time, the Frisian language was spoken along the entire southern North Sea coast. The 7th-century Frisian Kingdom (650–734) under King Aldegisel and King Redbad, had its centre of power in Utrecht.

Dorestad was the largest settlement (emporia) in northwestern Europe. It had grown around a former Roman fortress. It was a large, flourishing trading place, three kilometers long and situated where the rivers Rhine and Lek diverge southeast of Utrecht near the modern town of Wijk bij Duurstede.[46][47] Although inland, it was a North Sea trading centre that primarily handled goods from the Middle Rhineland.[47][48] Wine was among the major products traded at Dorestad, likely from vineyards south of Mainz.[48] It was also widely known because of its mint. Between 600 and around 719 Dorestad was often fought over between the Frisians and the Franks.

Franks

After Roman government in the area collapsed, the Franks expanded their territories until there were numerous small Frankish kingdoms, especially at Cologne, Tournai, Le Mans and Cambrai.[34][49] The kings of Tournai eventually came to subdue the other Frankish kings. By the 490s, Clovis I had conquered and united all the Frankish territories to the west of the Meuse, including those in the southern Netherlands. He continued his conquests into Gaul.

After the death of Clovis I in 511, his four sons partitioned his kingdom amongst themselves, with Theuderic I receiving the lands that were to become Austrasia (including the southern Netherlands). A line of kings descended from Theuderic ruled Austrasia until 555, when it was united with the other Frankish kingdoms of Chlothar I, who inherited all the Frankish realms by 558. He redivided the Frankish territory amongst his four sons, but the four kingdoms coalesced into three on the death of Charibert I in 567. Austrasia (including the southern Netherlands) was given to Sigebert I. The southern Netherlands remained the northern part of Austrasia until the rise of the Carolingians.

The Franks who expanded south into Gaul settled there and eventually adopted the Vulgar Latin of the local population.[18] However, a Germanic language was spoken as a second tongue by public officials in western Austrasia and Neustria as late as the 850s. It completely disappeared as a spoken language from these regions during the 10th century.[50] During this expansion to the south, many Frankish people remained in the north (i.e. southern Netherlands, Flanders and a small part of northern France). A widening cultural divide grew between the Franks remaining in the north and the rulers far to the south in what is now France.[49] Salian Franks continued to reside in their original homeland and the area directly to the south and to speak their original language, Old Frankish, which by the 9th century had evolved into Old Dutch.[18] A Dutch-French language boundary came into existence (but this was originally south of where it is today).[18][49] In the Maas and Rhine areas of the Netherlands, the Franks had political and trading centres, especially at Nijmegen and Maastricht.[49] These Franks remained in contact with the Frisians to the north, especially in places like Dorestad and Utrecht.

Modern doubts about the traditional Frisian, Frank and Saxon distinction

In the late 19th century, Dutch historians believed that the Franks, Frisians, and Saxons were the original ancestors of the Dutch people. Some went further by ascribing certain attributes, values and strengths to these various groups and proposing that they reflected 19th-century nationalist and religious views. In particular, it was believed that this theory explained why Belgium and the southern Netherlands (i.e. the Franks) had become Catholic and the northern Netherlands (Frisians and Saxons) had become Protestant. The success of this theory was partly due to anthropological theories based on a tribal paradigm. Being politically and geographically inclusive, and yet accounting for diversity, this theory was in accordance with the need for nation-building and integration during the 1890–1914 period. The theory was taught in Dutch schools.

However, the disadvantages of this historical interpretation became apparent. This tribal-based theory suggested that external borders were weak or non-existent and that there were clear-cut internal borders. This origins myth provided an historical premise, especially during the Second World War, for regional separatism and annexation to Germany. After 1945 the tribal paradigm lost its appeal for anthropological scholars and historians. When the accuracy of the three-tribe theme was fundamentally questioned, the theory fell out of favour.[33]

Due to the scarcity of written sources, knowledge of this period depends to a large degree on the interpretation of archaeological data. The traditional view of a clear-cut division between Frisians in the north and coast, Franks in the south and Saxons in the east has proven historically problematic.[51][52][53] Archeological evidence suggests dramatically different models for different regions, with demographic continuity for some parts of the country and depopulation and possible replacement in other parts, notably the coastal areas of Frisia and Holland.[54]

The emergence of the Dutch language

The language from which Old Dutch (also sometimes called Old West Low Franconian, Old Low Franconian or Old Frankish) arose is not known with certainty, but it is thought to be the language spoken by the Salian Franks. Even though the Franks are traditionally categorized as Weser-Rhine Germanic, Dutch has a number of Ingvaeonic characteristics and is classified by modern linguists as an Ingvaeonic language. Dutch also has a number of Old Saxon characteristics. There was a close relationship between Old Dutch, Old Saxon, Old English and Old Frisian. Because texts written in the language spoken by the Franks are almost non-existent, and Old Dutch texts scarce and fragmentary, not much is known about the development of Old Dutch. Old Dutch made the transition to Middle Dutch around 1150.[18]

Christianization

The Christianity that arrived in the Netherlands with the Romans appears not to have died out completely (in Maastricht, at least) after the withdrawal of the Romans in about 411.[49]

The Franks became Christians after their king Clovis I converted to Catholicism, an event which is traditionally set in 496. Christianity was introduced in the north after the conquest of Friesland by the Franks. The Saxons in the east were converted before the conquest of Saxony, and became Frankish allies.

Hiberno-Scottish and Anglo-Saxon missionaries, particularly Willibrord, Wulfram and Boniface, played an important role in converting the Frankish and Frisian peoples to Christianity by the 8th century. Boniface was martyred by the Frisians in Dokkum (754).

Frankish dominance and incorporation into the Holy Roman Empire

In the early 8th century the Frisians came increasingly into conflict with the Franks to the south, resulting in a series of wars in which the Frankish Empire eventually subjugated Frisia. In 734, at the Battle of the Boarn, the Frisians in the Netherlands were defeated by the Franks, who thereby conquered the area west of the Lauwers. The Franks then conquered the area east of the Lauwers in 785 when Charlemagne defeated Widukind.

The linguistic descendants of the Franks, the modern Dutch -speakers of the Netherlands and Flanders, seem to have broken with the endonym "Frank" around the 9th century. By this time Frankish identity had changed from an ethnic identity to a national identity, becoming localized and confined to the modern Franconia and principally to the French province of Île-de-France.[55]

Although the people no longer referred to themselves as "Franks", the Netherlands was still part of the Frankish empire of Charlemagne. Indeed, because of the Austrasian origins of the Carolingians in the area between the Rhine and the Maas, the cities of Aachen, Maastricht, Liège and Nijmegen were at the heart of Carolingian culture.[49] Charlemagne maintained his palatium[56] in Nijmegen at least four times.

The Carolingian empire would eventually include France, Germany, northern Italy and much of Western Europe. In 843, the Frankish empire was divided into three parts, giving rise to West Francia in the west, East Francia in the east, and Middle Francia in the centre. Most of what is today the Netherlands became part of Middle Francia; Flanders became part of West Francia. This division was an important factor in the historical distinction between Flanders and the other Dutch-speaking areas.

Middle Francia (Latin: Francia media) was an ephemeral Frankish kingdom that had no historical or ethnic identity to bind its varied peoples. It was created by the Treaty of Verdun in 843, which divided the Carolingian Empire among the sons of Louis the Pious. Situated between the realms of East and West Francia, Middle Francia comprised the Frankish territory between the rivers Rhine and Scheldt, the Frisian coast of the North Sea, the former Kingdom of Burgundy (except for a western portion, later known as Bourgogne), Provence and the Kingdom of Italy.

Middle Francia fell to Lothair I, the eldest son and successor of Louis the Pious, after an intermittent civil war with his younger brothers Louis the German and Charles the Bald. In acknowledgement of Lothair's Imperial title, Middle Francia contained the imperial cities of Aachen, the residence of Charlemagne, as well as Rome. In 855, on his deathbed at Prüm Abbey, Emperor Lothair I again partitioned his realm amongst his sons. Most of the lands north of the Alps, including the Netherlands, passed to Lothair II and consecutively were named Lotharingia. After Lothair II died in 869, Lotharingia was partitioned by his uncles Louis the German and Charles the Bald in the Treaty of Meerssen in 870. Although some of the Netherlands had come under Viking control, in 870 it technically became part of East Francia, which became the Holy Roman Empire in 962.

Viking raids

In the 9th and 10th centuries, the Vikings raided the largely defenceless Frisian and Frankish towns lying on the coast and along the rivers of the Low Countries. Although Vikings never settled in large numbers in those areas, they did set up long-term bases and were even acknowledged as lords in a few cases. In Dutch and Frisian historical tradition, the trading centre of Dorestad declined after Viking raids from 834 to 863; however, since no convincing Viking archaeological evidence has been found at the site (as of 2007), doubts about this have grown in recent years.[57]

One of the most important Viking families in the Low Countries was that of Rorik of Dorestad (based in Wieringen) and his brother the "younger Harald" (based in Walcheren), both thought to be nephews of Harald Klak.[58] Around 850, Lothair I acknowledged Rorik as ruler of most of Friesland. And again in 870, Rorik was received by Charles the Bald in Nijmegen, to whom he became a vassal. Viking raids continued during that period. Harald's son Rodulf and his men were killed by the people of Oostergo in 873. Rorik died sometime before 882.

Buried Viking treasures consisting mainly of silver have been found in the Low Countries. Two such treasures have been found in Wieringen. A large treasure found in Wieringen in 1996 dates from around 850 and is thought perhaps to have been connected to Rorik. The burial of such a valuable treasure is seen as an indication that there was a permanent settlement in Wieringen.[59]

Around 879, Godfrid arrived in Frisian lands as the head of a large force that terrorised the Low Countries. Using Ghent as his base, they ravaged Ghent, Maastricht, Liège, Stavelot, Prüm, Cologne, and Koblenz. Controlling most of Frisia between 882 and his death in 885, Godfrid became known to history as Godfrid, Duke of Frisia. His lordship over Frisia was acknowledged by Charles the Fat, to whom he became a vassal. Godfried was assassinated in 885, after which Gerolf of Holland assumed lordship and Viking rule of Frisia came to an end.

Viking raids of the Low Countries continued for over a century. Remains of Viking attacks dating from 880 to 890 have been found in Zutphen and Deventer. In 920, King Henry of Germany liberated Utrecht. According to a number of chronicles, the last attacks took place in the first decade of the 11th century and were directed at Tiel and/or Utrecht.[60]

These Viking raids occurred about the same time that French and German lords were fighting for supremacy over the middle empire that included the Netherlands, so their sway over this area was weak. Resistance to the Vikings, if any, came from local nobles, who gained in stature as a result.

High and Late Middle Ages (1000–1432)

Part of the Holy Roman Empire

The German kings and emperors ruled the Netherlands in the 10th and 11th century. Germany was called the Holy Roman Empire after the coronation of King Otto the Great as emperor. The Dutch city of Nijmegen used to be the spot of an important domain of the German emperors. Several German emperors were born and died there, including for example Byzantine empress Theophanu, who died in Nijmegen. Utrecht was also an important city and trading port at the time.

Political disunity

The Holy Roman Empire was not able to maintain political unity. In addition to the growing independence of the towns, local rulers turned their counties and duchies into private kingdoms and felt little sense of obligation to the emperor who reigned over large parts of the nation in name only. Large parts of what now comprise the Netherlands were governed by the Count of Holland, the Duke of Gelre, the Duke of Brabant and the Bishop of Utrecht. Friesland and Groningen in the north maintained their independence and were governed by the lower nobility.

The various feudal states were in a state of almost continual war. Gelre and Holland fought for control of Utrecht. Utrecht, whose bishop had in 1000 ruled over half of what is today the Netherlands, was marginalised as it experienced continuing difficulty in electing new bishops. At the same time, the dynasties of neighbouring states were more stable. Groningen, Drenthe and most of Gelre, which used to be part of Utrecht, became independent. Brabant tried to conquer its neighbours, but was not successful. Holland also tried to assert itself in Zeeland and Friesland, but its attempts failed.

The Frisians

The language and culture of most of the people who lived in the area that is now Holland were originally Frisian. The sparsely populated area was known as "West Friesland" (Westfriesland). As Frankish settlement progressed, the Frisians migrated away or were absorbed and the area quickly became Dutch. (The part of North Holland situated north of Alkmaar is still colloquially known as West Friesland).

The rest of Friesland in the north continued to maintain its independence during this time. It had its own institutions (collectively called the "Frisian freedom") and resented the imposition of the feudal system and the patriciate found in other European towns. They regarded themselves as allies of Switzerland. The Frisian battle cry was "better dead than a slave". They later lost their independence when they were defeated in 1498 by the German Landsknecht mercenaries of Duke Albrecht of Saxony-Meissen.

The rise of Holland

The center of power in these emerging independent territories was in the County of Holland. Originally granted as a fief to the Danish chieftain Rorik in return for loyalty to the emperor in 862, the region of Kennemara (the region around modern Haarlem) rapidly grew under Rorik's descendants in size and importance. By the early 11th century, Dirk III, Count of Holland was levying tolls on the Meuse estuary and was able to resist military intervention from his overlord, the Duke of Lower Lorraine.

In 1083, the name "Holland" first appears in a deed referring to a region corresponding more or less to the current province of South Holland and the southern half of what is now North Holland. Holland's influence continued to grow over the next two centuries. The counts of Holland conquered most of Zeeland but it was not until 1289 that Count Floris V was able to subjugate the Frisians in West Friesland (that is, the northern half of North Holland).

Expansion and growth

Around 1000 AD there were several agricultural developments (described sometimes as an agricultural revolution) that resulted in an increase in production, especially food production. The economy started to develop at a fast pace, and the higher productivity allowed workers to farm more land or to become tradesmen.

Much of the western Netherlands was barely inhabited between the end of the Roman period until around 1100 AD, when farmers from Flanders and Utrecht began purchasing the swampy land, draining it and cultivating it. This process happened quickly and the uninhabited territory was settled in a few generations. They built independent farms that were not part of villages, something unique in Europe at the time.

Guilds were established and markets developed as production exceeded local needs. Also, the introduction of currency made trading a much easier affair than it had been before. Existing towns grew and new towns sprang into existence around monasteries and castles, and a mercantile middle class began to develop in these urban areas. Commerce and town development increased as the population grew.

The Crusades were popular in the Low Countries and drew many to fight in the Holy Land. At home, there was relative peace. Viking pillaging had stopped. Both the Crusades and the relative peace at home contributed to trade and the growth in commerce.

Cities arose and flourished, especially in Flanders and Brabant. As the cities grew in wealth and power, they started to buy certain privileges for themselves from the sovereign, including city rights, the right to self-government and the right to pass laws. In practice, this meant that the wealthiest cities became quasi-independent republics in their own right. Two of the most important cities were Brugge and Antwerp (in Flanders) which would later develop into some of the most important cities and ports in Europe.

Hook and Cod Wars

%2C_gravin_van_Holland_en_Zeeland.jpg)

The Hook and Cod Wars (Dutch: Hoekse en Kabeljauwse twisten) were a series of wars and battles in the County of Holland between 1350 and 1490. Most of these wars were fought over the title of count of Holland, but some have argued that the underlying reason was because of the power struggle of the bourgeois in the cities against the ruling nobility.

The Cod faction generally consisted of the more progressive cities of Holland. The Hook faction consisted for a large part of the conservative noblemen. Some of the main figures in this multi-generational conflict were William IV, Margaret, William V, William VI, Count of Holland and Hainaut, John and Philip the Good, Duke of Burgundy. But perhaps the most well known is Jacqueline, Countess of Hainaut.

The conquest of the county of Holland by the Duke Philip the Good of Burgundy was an odd affair. Leading noblemen in Holland invited the duke to conquer Holland, even though he had no historical claim to it. Some historians say that the ruling class in Holland wanted Holland to integrate with the Flemish economic system and adopt Flemish legal institutions. Europe had been wracked by many civil wars in the 14th and 15th centuries, while Flanders had grown rich and enjoyed peace.

Burgundian and Habsburg period (1433–1567)

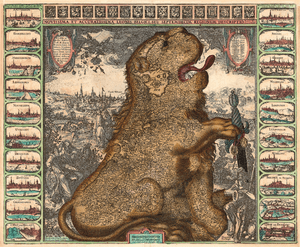

-NL.svg.png)

Burgundian period

Most of what is now the Netherlands and Belgium was eventually united by the Duke of Burgundy in 1433. Before the Burgundian union, the Dutch identified themselves by the town they lived in, their local duchy or county or as subjects of the Holy Roman Empire. The Burgundian period is when the Dutch began the road to nationhood.

Holland's trade developed rapidly, especially in the areas of shipping and transport. The new rulers defended Dutch trading interests. The fleets of Holland defeated the fleets of the Hanseatic League several times. Amsterdam grew and in the 15th century became the primary trading port in Europe for grain from the Baltic region. Amsterdam distributed grain to the major cities of Belgium, Northern France and England. This trade was vital to the people of Holland, because Holland could no longer produce enough grain to feed itself. Land drainage had caused the peat of the former wetlands to reduce to a level that was too low for drainage to be maintained.

Habsburg rule from Spain

Charles V (1500–58) was born and raised in the Flemish city of Ghent; he spoke French. Charles extended the Burgundian territory with the annexation of Tournai, Artois, Utrecht, Groningen and Guelders. The Seventeen Provinces had been unified by Charles's Burgundian ancestors, but nominally were fiefs of either France or the Holy Roman Empire. When he was a minor, his aunt Margaret acted as regent until 1515. France relinquished its ancient claim on Flanders in 1528.[61]

From 1515 to 1523, Charles's government in the Netherlands had to contend with the rebellion of Frisian peasants (led by Pier Gerlofs Donia and Wijard Jelckama). Gelre attempted to build up its own state in northeast Netherlands and northwest Germany. Lacking funds in the 16th century, Gelre had its soldiers provide for themselves by pillaging enemy terrain. These soldiers were a great menace to the Burgundian Netherlands, as when they pillaged The Hague.

The dukes of Burgundy over the years through astute marriages, purchases and wars, had taken control of the Seventeen Provinces that made up the Low Countries. They are now the Netherlands in the north, the Southern Netherlands (now Belgium) in the south, and Luxemburg in the southeast. Known as the "Burgundian Circle," these lands came under the control of the Habsburg family. Charles (1500–58) became the owner in 1506, but in 1515 he left to become king of Spain and later became the Holy Roman Emperor. Charles turned over control to regents (his close relatives), and in practice rule was exercised by Spaniards he controlled. The provinces each had their own governments and courts, controlled by the local nobility, and their own traditions and rights ("liberties") dating back centuries. Likewise the numerous cities had their own legal rights and local governments, usually controlled by the merchants, On top of this the Spanish had imposed an overall government, the Estates General of the Netherlands, with its own officials and courts.[62] The Spanish officials sent by Charles ignored traditions and the Dutch nobility as well as local officials, inciting an anti-Spanish sense of nationalism, and leading to the Dutch Revolt. With the emergence of the Protestant Reformation, Charles—now the Emperor—was determined to crush Protestantism and never compromise with it. Unrest began in the south, centered in the large rich metropolis of Antwerp. The Netherlands was an especially rich unit of the Spanish realm, especially after the Treaty of Cateau-Cambresis of 1559; it ended four decades of warfare between France and Spain and allowed Spain to reposition its army.[63]

In 1548, Charles granted the Netherlands status as an entity in which many of the laws of the Holy Roman Empire became obsolete. The "Transaction of Augsburg."[64] created the Burgundian Circle of the Holy Roman Empire, which comprised the Netherlands and Franche-Comté. A year later the Pragmatic Sanction of 1549 stated that the Seventeen Provinces could only be passed on to his heirs as a composite entity.[65]

The Reformation

During the 16th century, the Protestant Reformation rapidly gained ground in northern Europe, especially in its Lutheran and Calvinist forms.[66] Dutch Protestants, after initial repression, were tolerated by local authorities. By the 1560s, the Protestant community had become a significant influence in the Netherlands, although it clearly formed a minority then.[67] In a society dependent on trade, freedom and tolerance were considered essential. Nevertheless, the Catholic rulers Charles V, and later Philip II, made it their mission to defeat Protestantism, which was considered a heresy by the Catholic Church and a threat to the stability of the whole hierarchical political system. On the other hand, the intensely moralistic Dutch Protestants insisted their Biblical theology, sincere piety and humble lifestyle was morally superior to the luxurious habits and superficial religiosity of the ecclesiastical nobility.[68] The rulers' harsh punitive measures led to increasing grievances in the Netherlands, where the local governments had embarked on a course of peaceful coexistence. In the second half of the century, the situation escalated. Philip sent troops to crush the rebellion and make the Netherlands once more a Catholic region.[69]

In the first wave of the Reformation, Lutheranism won over the elites in Antwerp and the South. The Spanish successfully suppressed it there, and Lutheranism only flourished in east Friesland.[70]

The second wave of the Reformation, came in the form of Anabaptism, that was popular among ordinary farmers in Holland and Friesland. Anabaptists were socially very radical and equalitarian; they believed that the apocalypse was very near. They refused to live the old way, and began new communities, creating considerable chaos. A prominent Dutch Anabaptist was Menno Simons, who initiated the Mennonite church. The movement was allowed in the north, but never grew to a large scale.[71]

The third wave of the Reformation, that ultimately proved to be permanent, was Calvinism. It arrived in the Netherlands in the 1540s, attracting both the elite and the common population, especially in Flanders. The Catholic Spanish responded with harsh persecution and introduced the Inquisition of the Netherlands. Calvinists rebelled. First there was the iconoclasm in 1566, which was the systematic destruction of statues of saints and other Catholic devotional depictions in churches. In 1566, William the Silent, a Calvinist, started the Eighty Years' War to liberate all Dutch of whatever religion from Catholic Spain. Blum says, "His patience, tolerance, determination, concern for his people, and belief in government by consent held the Dutch together and kept alive their spirit of revolt."[72] The provinces of Holland and Zeeland, being mainly Calvinist by 1572, submitted to the rule of William. The other states remained almost entirely Catholic.[73][74]

Prelude to war

The Netherlands was a valuable part of the Spanish Empire, especially after the Treaty of Cateau-Cambresis of 1559. This treaty ended a forty-year period of warfare between France and Spain conducted in Italy from 1521 to 1559.[63] The Treaty of Cateau-Cambresis was somewhat of a watershed—not only for the battleground that Italy had been, but also for northern Europe. Spain had been keeping troops in the Netherlands to be ready to attack France from the north as well as from the south.

With the settlement of so many major issues between France and Spain by the Treaty of Cateau-Cambresis, there was no longer any reason to keep Spanish troops in the Netherlands. Thus, the people of the Netherlands could get on with their peacetime pursuits. As they did so they found that there was a great deal of demand for their products. Fishing had long been an important part of the economy of the Netherlands. However, now the fishing of herring alone came to occupy 2,000 boats operating out of Dutch ports. Spain, still the Dutch trader's best customer, was buying fifty large ships full of furniture and household utensils from Flanders merchants. Additionally, Dutch woolen goods were desired everywhere. The Netherlands bought and processed enough Spanish wool to sell four million florins of wool products through merchants in Bruges. So strong was the Dutch appetite for raw wool at this time that they bought nearly as much English wool as they did Spanish wool. Total commerce with England alone amounted to 24 million florins. Much of the export going to England resulted in pure profit to the Dutch because the exported items were of their own manufacture. The Netherlands was just starting to enter its "Golden Age." Brabant and Flanders were the richest and most flourishing parts of the Dutch Republic at the time.[75] The Netherlands was one of the richest places in the world. The population reached 3 million in 1560, with 25 cities of 10,000 people or more, by far the largest urban presence in Europe; with the trading and financial center of Antwerp being especially important (population 100,000). Spain could not afford to lose this rich land, nor allow it to fall from Catholic control. Thus came 80 years of warfare.

A devout Catholic, Philip was appalled by the success of the Reformation in the Low Countries, which had led to an increasing number of Calvinists. His attempts to enforce religious persecution of the Protestants, and his centralization of government, law enforcement, and taxes, made him unpopular and led to a revolt. Fernando Alvarez de Toledo, Duke of Alba, was sent with a Spanish Army to punish the unruly Dutch in 1567.[76]

The only opposition the Duke of Alba faced in his march across the Netherlands were the nobles, Lamoral, Count of Egmont; Philippe de Montmorency, Count of Horn and others. With the approach of Alba and the Spanish army, William the Silent of Orange fled to Germany with his three brothers and his whole family on 11 April 1567. The Duke of Alba sought to meet and negotiate with the nobles that now faced him with armies. However, when the nobles arrived in Brussels they were all arrested and Egmont and Horn were executed.[76] Alba then revoked all the prior treaties that Margaret, the Duchess of Parma had signed with the Protestants of the Netherlands and instituted the Inquisition to enforce the decrees of the Council of Trent.

The Eighty Years' War (1568–1648)

The Dutch War for Independence from Spain is frequently called the Eighty Years' War (1568–1648). The first fifty years (1568 through 1618) were uniquely a war between Spain and the Netherlands. During the last thirty years (1618–1648) the conflict between Spain and the Netherlands was submerged in the general European War that became known as the Thirty Years' War.[77] The seven rebellious provinces of the Netherlands were eventually united by the Union of Utrecht in 1579 and formed the Republic of the Seven United Netherlands (also known as the "United Provinces"). The Act of Abjuration or Plakkaat van Verlatinghe was signed on 26 July 1581, and was the formal declaration of independence of the northern Low Countries from the Spanish king.

William of Orange (Slot Dillenburg, 24 April 1533 – Delft, 10 July 1584), the founder of the Dutch royal family, led the Dutch during the first part of the war, following the death of Egmont and Horn in 1568. The very first years were a success for the Spanish troops. However, the Dutch countered subsequent sieges in Holland. In November and December 1572, all the citizens of Zutphen and Naarden were slaughtered by the Spanish. From 11 December that year the city of Haarlem was besieged, holding out for seven months until 13 July 1573. Oudewater was conquered by the Spanish on 7 August 1575, and most of its inhabitants were killed. Maastricht was besieged, sacked and destroyed twice in succession (in 1576 and 1579) by the Spanish.

In a war composed mostly of sieges rather than battles, Governor-General Alexander Farnese proved his mettle. His strategy was to offer generous terms for the surrender of a city: there would be no more massacres or looting; historic urban privileges were retained; there was a full pardon and amnesty; return to the Catholic Church would be gradual. The conservative Catholics in the south and east supported the Spanish. Farnese recaptured Antwerp and nearly all of what became Belgium.[78] Most of the Dutch-speaking territory in the Netherlands was taken from Spain, but not in Flanders, which to this day remains part of Belgium. Flanders was the most radical anti-Spanish territory. Many Flemish fled to Holland, among them half of the population of Antwerp, 3/4 of Bruges and Ghent and the entire population of Nieuwpoort, Dunkerque and countryside.[79] His successful campaign gave the Catholics control of the lower half of the Low Countries, and was part of the Catholic Counter-Reformation.

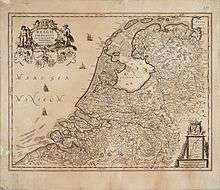

The war dragged on for another half century, but the main fighting was over. The Peace of Westphalia, signed in 1648, confirmed the independence of the United Provinces from Spain. The Dutch people started to develop a national identity since the 15th century, but they officially remained a part of the Holy Roman Empire until 1648. National identity was mainly formed by the province people came from. Holland was the most important province by far. The republic of the Seven Provinces came to be known as Holland across Europe.

The Catholics in the Netherlands were an outlawed minority that had been suppressed by the Calvinists. After 1572, however, they made a striking comeback (also as part of the Catholic Counter-Reformation), setting up seminaries, reforming their Church, and sending missionaries into Protestant districts. Laity often took the lead; the Calvinist government often arrested or harassed priests who seemed too effective. Catholic numbers stabilized at about a third of the population in the Netherlands; they were strongest in the southeast.[80][81]

Golden Age

During the Eighty Years' War the Dutch provinces became the most important trading centre of Northern Europe, replacing Flanders in this respect. During the Golden Age, there was a great flowering of trade, industry, the arts and the sciences in the Netherlands. In the 17th and 18th centuries, the Dutch were arguably the most economically wealthy and scientifically advanced of all European nations. This new, officially Calvinist nation flourished culturally and economically, creating what historian Simon Schama has called an "embarrassment of riches".[82] Speculation in the tulip trade led to a first stock market crash in 1637, but the economic crisis was soon overcome. Due to these developments the 17th century has been dubbed the Golden Age of the Netherlands.

The invention[83] of the sawmill enabled the construction of a massive fleet of ships for worldwide trading and for defence of the republic's economic interests by military means. National industries such as shipyards and sugar refineries expanded as well.

The Dutch, traditionally able seafarers and keen mapmakers,[84] obtained an increasingly dominant position in world trade, a position which before had been occupied by the Portuguese and Spaniards. In 1602 the Dutch East India Company (Dutch: Verenigde Oostindische Compagnie or VOC) was founded. It was the first-ever multinational corporation, financed by shares that established the first modern stock exchange. It became the world's largest commercial enterprise of the 17th century. To finance the growing trade within the region, the Bank of Amsterdam was established in 1609, the precursor to, if not the first true central bank.[85]

Dutch ships hunted whales off Svalbard, traded spices in India and Indonesia (via the Dutch East India Company) and founded colonies in New Amsterdam (now New York), South Africa and the West Indies. In addition some Portuguese colonies were conquered, namely in Northeastern Brazil, Angola, Indonesia and Ceylon. In 1640 by the Dutch East India Company began a trade monopoly with Japan through the trading post on Dejima.

The Dutch also dominated trade between European countries. The Low Countries were favorably positioned on a crossing of east-west and north-south trade routes and connected to a large German hinterland through the Rhine river. Dutch traders shipped wine from France and Portugal to the Baltic lands and returned with grain destined for countries around the Mediterranean Sea. By the 1680s, an average of nearly 1000 Dutch ships entered the Baltic Sea each year.[86] The Dutch were able to gain control of much of the trade with the nascent English colonies in North America and following the end of war with Spain in 1648, Dutch trade with that country also flourished.

._Natuurkundige_te_Delft_Rijksmuseum_SK-A-957.jpeg)

Renaissance Humanism, of which Desiderius Erasmus (c. 1466–1536) was an important advocate, had also gained a firm foothold and was partially responsible for a climate of tolerance. Overall, levels of tolerance were sufficiently high to attract religious refugees from other countries, notably Jewish merchants from Portugal who brought much wealth with them. The revocation of the Edict of Nantes in France in 1685 resulted in the immigration of many French Huguenots, many of whom were shopkeepers or scientists. Still tolerance had its limits, as philosopher Baruch de Spinoza (1632–1677) would find out. Due to its climate of intellectual tolerance the Dutch Republic attracted scientists and other thinkers from all over Europe. Especially the renowned University of Leiden (established in 1575 by the Dutch stadtholder, William of Oranje, as a token of gratitude for Leiden's fierce resistance against Spain during the Eighty Years' War) became a gathering place for these people. For instance French philosopher René Descartes lived in Leiden from 1628 until 1649.

Dutch lawyers were famous for their knowledge of international law of the sea and commercial law. Hugo Grotius (1583–1645) played a leading part in the foundation of international law. Again due to the Dutch climate of tolerance, book publishers flourished. Many books about religion, philosophy and science that might have been deemed controversial abroad were printed in the Netherlands and secretly exported to other countries. Thus during the 17th century the Dutch Republic became more and more Europe's publishing house.

Christiaan Huygens (1629–1695) was a famous astronomer, physicist and mathematician. He invented the pendulum clock, which was a major step forward towards exact timekeeping. He contributed to the fields of optics. The most famous Dutch scientist in the area of optics is certainly Anton van Leeuwenhoek, who invented or greatly improved the microscope (opinions differ) and was the first to methodically study microscopic life, thus laying the foundations for the field of microbiology. Famous Dutch hydraulic engineer Jan Leeghwater (1575–1650) gained important victories in The Netherlands's eternal battle against the sea. Leeghwater added a considerable amount of land to the republic by converting several large lakes into polders, pumping all water out with windmills.

Painting was the dominant art form in 17th-century Holland. Dutch Golden Age painting followed many of the tendencies that dominated Baroque art in other parts of Europe, as with the Utrecht Caravaggisti, but was the leader in developing the subjects of still life, landscape, and genre painting. Portraiture were also popular, but history painting – traditionally the most-elevated genre struggled to find buyers. Church art was virtually non-existent, and little sculpture of any kind produced. While art collecting and painting for the open market was also common elsewhere, art historians point to the growing number of wealthy Dutch middle-class and successful mercantile patrons as driving forces in the popularity of certain pictorial subjects.[87] Today, the best-known painters of the Dutch Golden Age are the period's most dominant figure Rembrandt, the Delft master of genre Johannes Vermeer, the innovative landscape painter Jacob van Ruisdael, and Frans Hals, who infused new life into portraiture. Some notable artistic styles and trends include Haarlem Mannerism, Utrecht Caravaggism, the School of Delft, the Leiden fijnschilders, and Dutch classicism.

Due to the thriving economy, cities expanded greatly. New town halls, weighhouses and storehouses were built. Merchants that had gained a fortune ordered a new house built along one of the many new canals that were dug out in and around many cities (for defence and transport purposes), a house with an ornamented façade that befitted their new status. In the countryside, many new castles and stately homes were built. Most of them have not survived. Starting at 1595 Reformed churches were commissioned, many of which are still landmarks today. The most famous Dutch architects of the 17th century were Jacob van Campen, Pieter Post, Pieter Vingbooms, Lieven de Key, Hendrick de Keyser. Overall, Dutch architecture, which generally combined traditional building styles with some foreign elements, did not develop to the level of painting.

The Golden Age was also an important time for developments in literature. Some of the major figures of this period were Gerbrand Adriaenszoon Bredero, Jacob Cats, Pieter Corneliszoon Hooft and Joost van den Vondel. Since Latin was the lingua franca of education, relatively few men could speak, write, and read Dutch all at the same time.

Music did not develop very much in the Netherlands since the Calvinists considered it an unnecessary extravagance, and organ music was forbidden in Reformed Church services, although it remained common at secular functions.

Dutch Empire

The Dutch in the Americas

The Dutch West India Company was a chartered company (known as the "GWC") of Dutch merchants. On 2 June 1621, it was granted a charter for a trade monopoly in the West Indies (meaning the Caribbean) by the Republic of the Seven United Netherlands and given jurisdiction over the African slave trade, Brazil, the Caribbean, and North America. Its area of operations stretched from West Africa to the Americas, and the Pacific islands. The company became instrumental in the Dutch colonization of the Americas. The first forts and settlements in Guyana and on the Amazon River date from the 1590s. Actual colonization, with Dutch settling in the new lands, was not as common as with England and France. Many of the Dutch settlements were lost or abandoned by the end of that century, but the Netherlands managed to retain possession of Suriname and a number of Dutch Caribbean islands.

The colony was a private business venture to exploit the fur trade in beaver pelts. New Netherland was slowly settled during its first decades, partially as a result of policy mismanagement by the Dutch West India Company (WIC), and conflicts with Native Americans. During the 1650s, the colony experienced dramatic growth and became a major port for trade in the Atlantic World, tolerating a highly diverse ethnic mix. The surrender of Fort Amsterdam to the British control in 1664 was formalized in 1667, contributing to the Second Anglo–Dutch War. In 1673 the Dutch re-took the area, but later relinquished it under the 5 April 1674 Treaty of Westminster ending the Third Anglo-Dutch War.[88]

Descendants of the original settlers played a prominent role in the History of the United States, as typified by the Roosevelt and Vanderbilt families. The Hudson Valley still boasts a Dutch heritage. The concepts of civil liberties and pluralism introduced in the province became mainstays of American political and social life.[89]

Slave trade

Although slavery was illegal inside the Netherlands it flourished in the Dutch Empire, and helped support the economy.[90] In 1619 The Netherlands took the lead in building a large-scale slave trade between Africa and Virginia, by 1650 becoming the pre-eminent slave trading country in Europe. It was overtaken by Britain around 1700. Historians agree that in all the Dutch shipped about 550,000 African slaves across the Atlantic, about 75,000 of whom died on board before reaching their destinations. From 1596 to 1829, the Dutch traders sold 250,000 slaves in the Dutch Guianas, 142,000 in the Dutch Caribbean islands, and 28,000 in Dutch Brazil.[91] In addition, tens of thousands of slaves, mostly from India and some from Africa, were carried to the Dutch East Indies[92] and slaves from the East Indies to Africa and the West Indies.

The Dutch in Asia: The Dutch East India Company

The Dutch East India Company, called the VOC, began in 1602, when the government gave it a monopoly to trade with Asia, mainly to Mughal India. It had many world firsts—the first multinational corporation, the first company to issue stock, and was the first megacorporation, possessing quasi-governmental powers, including the ability to wage war, negotiate treaties, coin money, and establish colonial settlements.[93]

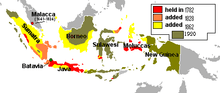

England and France soon copied its model but could not match its record. Between 1602 and 1796 the VOC sent almost a million Europeans to work in the Asia trade on 4,785 ships. It returned over 2.5 million tons of Asian trade goods. The VOC enjoyed huge profits from its spice monopoly through most of the 17th century. The VOC was active chiefly in the Dutch East Indies, now Indonesia, where its base was Batavia (now Jakarta), which remained an important trading concern and paid an 18% annual dividend for almost 200 years; colonized parts of Taiwan between 1624–1662 and 1664–1667 and the only western trading post in Japan, Dejima.

During the period of Proto-industrialization, the empire received 50% of textiles and 80% of silks import from the India's Mughal Empire, chiefly from its most developed region known as Bengal Subah.[94][95][96][97]

By the 17th century, the Dutch East India Company established their base in parts of Ceylon (modern-day Sri Lanka). Afterward, they established ports in Dutch occupied Malabar, leading to Dutch settlements and trading posts in India. However, their expansion into India was halted, after their defeat in the Battle of Colachel by the Kingdom of Travancore, during the Travancore-Dutch War. The Dutch never recovered from the defeat and no longer posed a large colonial threat to India.[98][99]

Eventually, the Dutch East India Company was weighted down by corruption, the VOC went bankrupt in 1800. Its possessions were taken over by the government and turned into the Dutch East Indies.

The Dutch in Africa

In 1647, a Dutch vessel was wrecked in the present-day Table Bay at Cape Town. The marooned crew, the first Europeans to attempt settlement in the area, built a fort and stayed for a year until they were rescued. Shortly thereafter, the Dutch East India Company (in the Dutch of the day: Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie, or VOC) decided to establish a permanent settlement. The VOC, one of the major European trading houses sailing the spice route to East Asia, had no intention of colonizing the area, instead wanting only to establish a secure base camp where passing ships could shelter, and where hungry sailors could stock up on fresh supplies of meat, fruit, and vegetables. To this end, a small VOC expedition under the command of Jan van Riebeeck reached Table Bay on 6 April 1652.[100]

To remedy a labour shortage, the VOC released a small number of VOC employees from their contracts and permitted them to establish farms with which they would supply the VOC settlement from their harvests. This arrangement proved highly successful, producing abundant supplies of fruit, vegetables, wheat, and wine; they also later raised livestock. The small initial group of "free burghers", as these farmers were known, steadily increased in number and began to expand their farms further north and east.

The majority of burghers had Dutch ancestry and belonged to the Calvinist Reformed Church of the Netherlands, but there were also numerous Germans as well as some Scandinavians. In 1688 the Dutch and the Germans were joined by French Huguenots, also Calvinists, who were fleeing religious persecution in France under King Louis XIV. The Huguenots in South Africa were absorbed into the Dutch population but they played a prominent role in South Africa's history.

From the beginning, the VOC used the cape as a place to supply ships travelling between the Netherlands and the Dutch East Indies. There was a close association between the cape and these Dutch possessions in the far east. Van Riebeeck and the VOC began to import large numbers of slaves, primarily from Madagascar and Indonesia. These slaves often married Dutch settlers, and their descendants became known as the Cape Coloureds and the Cape Malays.

During the 18th century, the Dutch settlement in the area of the cape grew and prospered. By the late 1700s, the Cape Colony was one of the best developed European settlements outside Europe or the Americas.[101] The two bases of the Cape Colony's economy for almost the entirety of its history were shipping and agriculture. Its strategic position meant that almost every ship sailing between Europe and Asia stopped off at the colony's capital Cape Town. The supplying of these ships with fresh provisions, fruit, and wine provided a very large market for the surplus produce of the colony.[101]