Crime in the United Kingdom

Crime in the United Kingdom describes acts of violent crime and non-violent crime that take place within the United Kingdom. Courts and police systems are separated into three sections, based on the different judicial systems of England and Wales, Scotland, and Northern Ireland.

Responsibility for crime in England and Wales is split between the Home Office, the government department responsible for reducing and preventing crime,[1] along with law enforcement in the United Kingdom; and the Ministry of Justice, which runs the Justice system, including its courts and prisons.[2] In Scotland, this responsibility falls on the Crown Office and Procurator Fiscal Service, which acts as the sole public prosecutor in Scotland, and is therefore responsible for the prosecution of crime in Scotland.[3]

History

In its history, the United Kingdom has had a relatively normal relationship with crime. The United Kingdom’s crime rate remains relatively low when compared to the rest of the world, especially among first world countries. As of 2019, the United Kingdom sits in 174th place for intentional homicide victims per 100,000 inhabitants at 1.20.[4] While the United Kingdom remains a relatively peaceful country, as of January 2018 police figures have shown a sharp increase in violent crime and sex offences rates over the last few years.[5]

Comparing police-recorded crime rates in the long term is difficult as police recording practices, the reliability of police recording and victims' willingness to report crime have changed over the years.[6][7][8][9]

Criminal justice system

England and Wales

There are two kinds of criminal trial in England and Wales: 'summary' and 'on indictment'. For an adult, summary trials take place in a magistrates' court, while trials on indictment take place in the Crown Court. Despite the possibility of two venues for trial, almost all criminal cases, however serious, commence in the magistrates' courts. Offences may also be deemed 'either way', depending on the seriousness of the individual offence. This means they may be tried in either the Magistrates or Crown Court depending on the circumstances. A person may even be convicted by the Magistrates court and sent to the Crown for sentence (where the magistrates feel they do not have adequate sentencing powers). Further more, even if the Magistrates retain the jurisdiction of an offence, the defendant has the right to elect for a Crown Court trial by jury. The jury is selected independently of the prosecution and the defence.

Scotland

The lowest level of criminal courts in Scotland are justice of the peace courts. Compared to the English-Welsh magistrates court, their powers are more restricted. For example, they can only pass a prison sentence of up to 60 days.[10] The Sheriff Court is the main criminal court. The Sheriff Court may be conducted for 'summary cases' or 'solemn cases'. The former is used for less serious crimes, in which the sheriff (judge) presides alone, while the latter is a jury trial. From 10 December 2007, the maximum penalty that may be imposed in summary cases is 12 months' imprisonment or a £10,000 fine, in solemn cases 5 years' imprisonment or an unlimited fine.[11] The highest criminal court in Scotland is the High Court of Justiciary. This is the trial court for the most serious crimes (e.g. murder) and an appeal court for other criminal cases.[12]

Among the differences with common law legal systems are that juries in Scotland have 15 members, and only need a simple majority in order to give a verdict. Scottish courts can also give three verdicts: "guilty", "not guilty" and "not proven" (which is also an acquittal).[12]

Northern Ireland

In Northern Ireland, magistrates' courts hear less-serious criminal cases and conduct preliminary hearings in more serious criminal cases. The Crown Court in Northern Ireland hears more serious criminal cases. These are indictable offences and "either way" offences which are committed for trial in the Crown Court rather than the magistrates' courts. Northern Ireland has its own judicial system. The Lord Chief Justice of Northern Ireland is the entity that sits at the head of this system.[13] The Department of Justice is the department responsible for the administration of the courts, which it runs through the Northern Ireland Courts and Tribunals Service. On top of this, the Department also has responsibility for policy and legislation about criminal law, legal aid policy, the police, prisons and probation.[14] Similar to the justice system in the United States, defendants are innocent until proven guilty and on top of this in order to be proven guilty evidence must lead the judge or jury to make a decision based on the fact that it was “beyond reasonable doubt”.[15]

Extent of crime

England and Wales

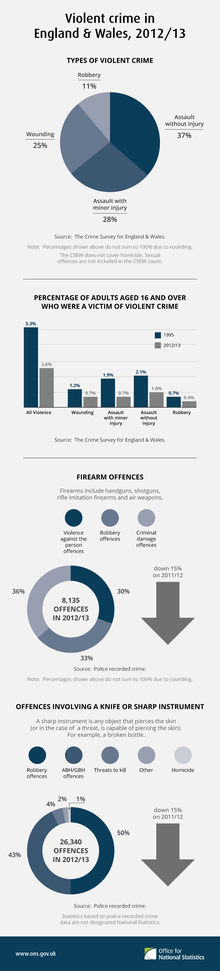

In England and Wales, there were 618,000 recorded "violence against the person" crimes which caused an injury in 2015. Other areas of crime included robbery (124,000), burglary (713,000) and vehicle theft (874,000).[16] England and Wales had a prison population of 83 430 (2018 estimate), equivalent to 179 people per 100 000. This is considerably less than the USA (762) but more than the Republic of Ireland (76). and a little more than the EU average (123).[17] The homicide rate in the UK was 1.2 per 100,000 in 2016[18], the third highest rate in Western Europe, after Belgium and France. The homicide rate in England and Wales increased 39% from the 38 year low of 0.89 per 100,000 in 2015 to a decade high of 1.23 per 100,000 in 2018.

Crime in London was the highest in England and Wales in 2009 (111 per 1000 of the population), followed by Greater Manchester (101 per 1000).[19]

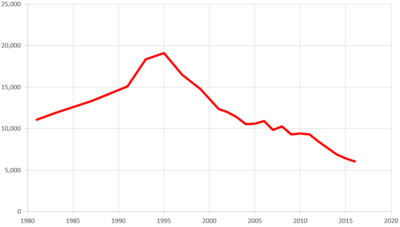

In most years since 1995, crime rates in England and Wales have declined,[6] although there was a rise in violent crime in the late 2010s.[5][21][6] In 2015, the Crime Survey for England and Wales found that crime in England and Wales was at its lowest level since the CSEW began in 1981, having decreased dramatically from its peak in 1995 and by 31% in 2010-15.[16] For example, the number of violent crimes declined from 4.2 million in 1994-95 to 1.32 million in 2014-15 with little change over the next few years.[16]

Scotland

In 2018–9, there were 60 homicide victims in Scotland,[22] a slight increase on the previous year. In the third quarter of 2009, there were a little over 17,000 full time equivalent serving police officers. There were around 375,000 crimes in 2008–9, a fall of 2% on the previous year. These included around 12,500 non-sexual violent acts, 168,000 crimes of dishonesty (housebreaking, theft and shoplifting are included in this category) and 110,000 acts of fire-raising and vandalism. In the 2008–9 period, there was a prison population in Scotland of about 7,300,[22] equating to 142 people per 100,000 population, very similar to England and Wales.[23]

Northern Ireland

Between April 2008 and 2009, there were just over 110,000 crimes recorded by the Police Service of Northern Ireland, an increase of 1.5% on the previous year.[24] As of 2020, Northern Ireland has around 6 873 serving full-time equivalent police positions [25], and in 2019 had a prison population of 1,448, 83 per 100,000 of the population, lower than the rest of the United Kingdom.[26]

Real crime stories

In Early Modern Britain, real crime stories were a popular form of entertainment. These stories were written about in pamphlets, broadsides, and chapbooks, such as The Newgate Calendar. These real crime stories were the subject of popular gossip and discussion of the day. While only a few people may have been able to attend a trial or an execution, these stories allowed for the entertainment of such events to be extended to a much greater population.[27] These crime stories depicted the gruesome details of criminal acts, trials and executions with the intent to "articulate a particular set of values, inculcate a certain behavioral model and bolster a social order perceived as threatened".[28]

The publication of these stories was done in order for the larger population to learn from the mistakes of their fellow Englishmen. They stressed the idea of learning from others wrongdoings to the extent that they would place warnings within the epitaphs of executed criminals. For example, in the epitaph of John Smith, a highway thief and murderer, said, "thereto remain, a Terrour to affright All wicked Men that do in Sins delight...this is the Reason, and the Cause that they May Warning take."[29] The epitaph ends with the Latin phrase "Faelix quem faciunt aliena pericula cantum” which means “fortunate the man who learns caution from the perils of others."

See also

- Crime statistics in the United Kingdom

- Race and crime in the United Kingdom

- Gangs in the United Kingdom

- Unsolved murders in the UK

- Major crimes in the United Kingdom

- Terrorism in the United Kingdom

- Sexual offences in the United Kingdom

Regional:

- Crime in England

- Crime in Wales

- Crime in Northern Ireland

- Crime in Scotland

Cities:

- Crime in Liverpool

- Crime in London

- Gun crime in south Manchester

References

- "Crime and Victims". homeoffice.gov.uk. The Home Office. Archived from the original on 22 December 2009. Retrieved 24 January 2010.

- "About Us". Ministry for Justice. 2009. Archived from the original on 23 January 2010. Retrieved 24 January 2010.

- "Guide to the Crown Office and Procurator Fiscal Service". Crown Office and Procurator Fiscal Service. 2008. Archived from the original on 16 July 2011. Retrieved 24 January 2010.

- "Intentional homicide victims | Statistics and Data". dataunodc.un.org. Archived from the original on 26 July 2019. Retrieved 7 June 2018.

- "Violent crime rising, police figures suggest". 25 January 2018. Archived from the original on 19 April 2019. Retrieved 19 April 2019.

- "Violent crime is not at record levels". Full Fact. 1 February 2019. Archived from the original on 27 September 2019. Retrieved 23 January 2020.

- "Victims let down by poor crime-recording". Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 11 May 2015.

- "Crime-recording: making the victim count". Archived from the original on 18 June 2015. Retrieved 11 May 2015.

- "Whistleblowers' diary: 'no criming' the stats - The Justice Gap". 18 November 2014. Archived from the original on 18 May 2015. Retrieved 11 May 2015.

- JP Court Bench Book: "Lay Justice". Judicial Studies Committee. Archived from the original on 1 November 2009. Retrieved 9 August 2010.

- Part III of the Criminal Proceedings etc. (Reform) (Scotland) Act 2007

- www.bbc.com https://www.bbc.co.uk/bitesize/guides/z83wsg8/revision/1. Retrieved 23 January 2020. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - "Introduction to the justice system". nidirect. 30 December 2015. Archived from the original on 19 April 2019. Retrieved 19 April 2019.

- "Introduction to the justice system". nidirect. 30 December 2015. Archived from the original on 19 April 2019. Retrieved 19 April 2019.

- "Introduction to the justice system". nidirect. 30 December 2015. Archived from the original on 19 April 2019. Retrieved 19 April 2019.

- "Bulletin Tables - Crime in England and Wales, Year Ending December 2015". Office for National Statistics. Archived from the original on 27 January 2020. Retrieved 21 April 2016.

- "UK Prison population statistics". House of Commons Library. 2019. Archived from the original on 17 December 2019. Retrieved 14 January 2020.

- List of countries by intentional homicide rate#By country

- Simon Rogers (22 April 2010). "Crime rates where you live". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 1 August 2013. Retrieved 5 July 2010.

- "Crime in England and Wales: year ending Dec 2016". Archived from the original on 2 May 2017. Retrieved 2 May 2017.

- "Man in 60s stabbed to death in broad daylight outside west London pub". Telegraph Media Group Limited. 25 August 2019. Archived from the original on 25 August 2019. Retrieved 25 August 2019.

- The Scottish Government (29 October 2019). "Homicide in Scotland 2018-2019: statistics". Archived from the original on 14 January 2020. Retrieved 14 January 2020.

- "Annual Abstract of Statistics". National Office of Statistics. 2009. Archived from the original on 28 January 2009. Retrieved 23 January 2009.

- "The PSNI's Statistical Report" (PDF). Police Service of Northern Ireland. 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 February 2010. Retrieved 25 January 2010.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 27 February 2018. Retrieved 17 February 2020.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 17 February 2020. Retrieved 17 February 2020.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Sharpe, J. A. (1 May 1985). ""last Dying Speeches": Religion, Ideology and Public Execution in Seventeenth-Century England"". Past and Present. 107 (1): 144–167. doi:10.1093/past/107.1.144.

- Sharpe, J. A. (1 May 1985). ""last Dying Speeches": Religion, Ideology and Public Execution in Seventeenth-Century England"". Past and Present. 107 (1): 144–167. doi:10.1093/past/107.1.144.

- "An epitaph on Mr. John Smith, alias Ashburnham". Archived from the original on 1 June 2016. Retrieved 9 April 2020.

External links

- Scottish Centre for Crime and Justice Research, a well-respected academic research centre focusing on crime and justice issues

- United Kingdom Black Markets Crime statistics on various illicit activities in the United Kingdom

- Historic Databases