Mercia

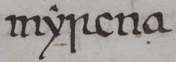

Mercia (/ˈmɜːrʃiə, -ʃə/;[1] Old English: Miercna rīċe; Latin: Merciorum regnum) was one of the kingdoms of the Anglo-Saxon Heptarchy. The name is a Latinisation of the Old English Mierce or Myrce (West Saxon dialect; Merce in the Mercian dialect itself), meaning "border people" (see March). Mercia dominated what would later become England for three centuries, subsequently going into a gradual decline while Wessex eventually conquered and united all the kingdoms into the Kingdom of England.[2]

Kingdom of Mercia Miercna rīċe (Old English) Merciorum regnum (Latin) | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 527–918 | |||||||||||||||

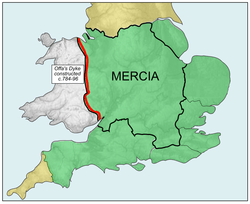

The Kingdom of Mercia (thick line) and the kingdom's extent during the Mercian Supremacy (green shading) | |||||||||||||||

| Status | Independent kingdom (527–879) Client state of Wessex (c. 879–918) | ||||||||||||||

| Capital | Tamworth | ||||||||||||||

| Common languages | Old English, Latin | ||||||||||||||

| Religion | Paganism, Christianity | ||||||||||||||

| Government | Absolute monarchy | ||||||||||||||

| Monarch | |||||||||||||||

• 527–? | Icel (first) | ||||||||||||||

• c. 626–655 | Penda | ||||||||||||||

• 658-675 | Wulfhere | ||||||||||||||

• 716–757 | Ethelbald | ||||||||||||||

• 757–796 | Offa | ||||||||||||||

• 796–821 | Coenwulf | ||||||||||||||

• 821–823 | Ceolwulf | ||||||||||||||

• 823–826 | Beornwulf | ||||||||||||||

• c. 881–911 | Ethelred | ||||||||||||||

• 911–918 | Æthelflæd | ||||||||||||||

• 918 | Ælfwynn (last) | ||||||||||||||

| Legislature | Witenagemot | ||||||||||||||

| Historical era | Heptarchy | ||||||||||||||

• Established | 527 | ||||||||||||||

• Disestablished | 918 | ||||||||||||||

| Currency | Sceat | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| Today part of |

| ||||||||||||||

The kingdom was centred on the valley of the River Trent and its tributaries, in the region now known as the English Midlands. The court moved around the kingdom, and there was no fixed capital city. Early in its existence Repton seems to have been the location of an important royal estate. According to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, it was from Repton in 873–874 that the Great Heathen Army deposed the King of Mercia. Slightly earlier, King Offa seems to have favoured Tamworth. It was there where he was crowned and spent many a Christmas.

For 300 years (between 600 and 900), having annexed or gained submissions from five of the other six kingdoms of the Heptarchy (East Anglia, Essex, Kent, Sussex and Wessex), Mercia dominated England south of the River Humber: this period is known as the Mercian Supremacy. The reign of King Offa, who is best remembered for his Dyke that designated the boundary between Mercia and the Welsh kingdoms, is sometimes known as the "Golden Age of Mercia". Nicholas Brooks noted that "the Mercians stand out as by far the most successful of the various early Anglo-Saxon peoples until the later ninth century",[3] and some historians, such as Sir Frank Stenton, believe the unification of England south of the Humber estuary was achieved during the reign of Offa.[4]

Mercia was a pagan kingdom; King Peada converted to Christianity around 656, and Christianity was firmly established in the kingdom by the late 7th century. The Diocese of Mercia was founded in 656, with the first bishop, Diuma, based at Repton. After 13 years at Repton, in 669 the fifth bishop, Saint Chad, moved the bishopric to Lichfield, where it has been based since. In 691, the Diocese of Mercia became the Diocese of Lichfield. For a brief period between 787 and 799 the diocese was an archbishopric, although it was dissolved in 803. The current bishop, Michael Ipgrave, is the 99th since the diocese was established.

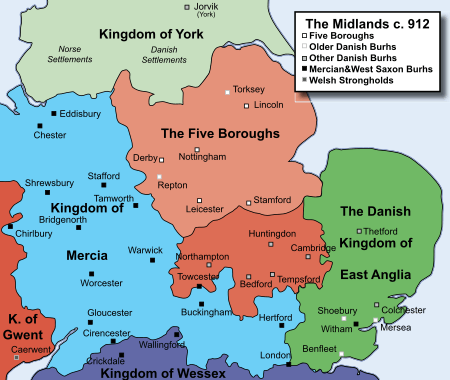

At the end of the 9th century, following the invasions of the Vikings and their Great Heathen Army, much of the former Mercian territory was absorbed into the Danelaw. At its height, the Danelaw included London, all of East Anglia and most of the North of England.

The final Mercian king, Ceolwulf II, died in 879; the kingdom appears to have thereby lost its political independence. Initially, it was ruled by a lord or ealdorman under the overlordship of Alfred the Great, who styled himself "King of the Anglo-Saxons". The kingdom had a brief period of independence in the mid-10th century, and again very briefly in 1016; however, by this time, it was viewed as a province within the Kingdom of England, not an independent kingdom.

Mercia is still used as a geographic designation, and the name is used by a wide range of organisations, including military units, public, commercial and voluntary bodies.

In the early Middle Ages

Early history

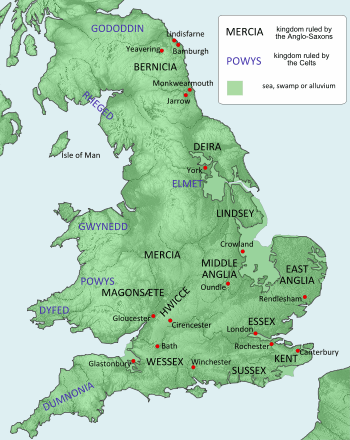

Mercia's exact evolution at the start of the Anglo-Saxon era remains more obscure than that of Northumbria, Kent, or even Wessex. Mercia developed an effective political structure and adopted Christianity later than the other kingdoms.[5] Archaeological surveys show that Angles settled the lands north of the River Thames by the 6th century. The name "Mercia" is Old English for "boundary folk" (see Welsh Marches), and the traditional interpretation is that the kingdom originated along the frontier between the native Welsh and the Anglo-Saxon invaders. However, P. Hunter Blair argued an alternative interpretation: that they emerged along the frontier between Northumbria and the inhabitants of the Trent river valley.[6]

While its earliest boundaries will never be known, there is general agreement that the territory that was called "the first of the Mercians" in the Tribal Hidage covered much of south Derbyshire, Leicestershire, Nottinghamshire, Northamptonshire, Staffordshire and northern Warwickshire.[7]

The earliest person named in any records as a king of Mercia is Creoda, said to have been the great-grandson of Icel. Coming to power around 584, he built a fortress at Tamworth which became the seat of Mercia's kings.[8] His son Pybba succeeded him in 593. Cearl, a kinsman of Creoda, followed Pybba in 606; in 615, Cearl gave his daughter Cwenburga in marriage to Edwin, king of Deira, whom he had sheltered while he was an exiled prince.[9]

The Mercian kings were the only Anglo-Saxon Heptarchy ruling house known to claim a direct family link with a pre-migration Continental Germanic monarchy.[10]

Penda and the Mercian Supremacy

The next Mercian king, Penda, ruled from about 626 or 633 until 655. Some of what is known about Penda comes from the hostile account of Bede, who disliked him – both as an enemy to Bede's own Northumbria and as a pagan. However, Bede admits that Penda freely allowed Christian missionaries from Lindisfarne into Mercia and did not restrain them from preaching. In 633 Penda and his ally Cadwallon of Gwynedd defeated and killed Edwin, who had become not only ruler of the newly unified Northumbria, but bretwalda, or high king, over the southern kingdoms. When another Northumbrian king, Oswald, arose and again claimed overlordship of the south, he also suffered defeat and death at the hands of Penda and his allies – in 642 at the Battle of Maserfield. In 655, after a period of confusion in Northumbria, Penda brought 30 sub-kings to fight the new Northumbrian king Oswiu at the Battle of Winwaed, in which Penda in turn lost the battle and his life.[11]

The battle led to a temporary collapse of Mercian power. Penda's son Peada, who had converted to Christianity at Repton in 653, succeeded his father as king of Mercia; Oswiu set up Peada as an under-king; but in the spring of 656 he was murdered and Oswiu assumed direct control of the whole of Mercia. A Mercian revolt in 658 threw off Northumbrian domination and resulted in the appearance of another son of Penda, Wulfhere, who ruled Mercia as an independent kingdom (though he apparently continued to render tribute to Northumbria for a while) until his death in 675. Wulfhere initially succeeded in restoring the power of Mercia, but the end of his reign saw a serious defeat by Northumbria. The next king, Æthelred, defeated Northumbria in the Battle of the Trent in 679, settling once and for all the long-disputed control of the former kingdom of Lindsey. Æthelred was succeeded by Cœnred, son of Wulfhere; both these kings became better known for their religious activities than anything else, but the king who succeeded them in 709, Ceolred, is said in a letter of Saint Boniface to have been a dissolute youth who died insane. So ended the rule of the direct descendants of Penda.[5]

At some point before the accession of Æthelbald in 716 the Mercians conquered the region around Wroxeter, known to the Welsh as Pengwern or as "The Paradise of Powys". Elegies written in the persona of its dispossessed rulers record the sorrow at this loss.[12]

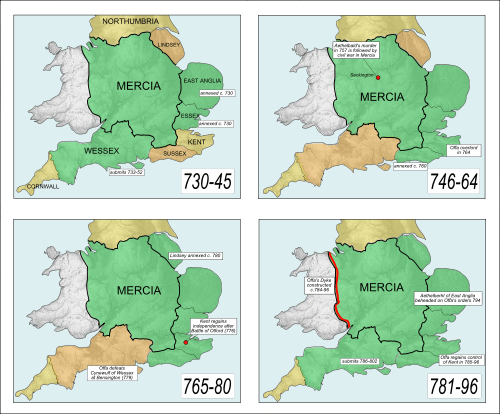

The next important king of Mercia, Æthelbald, reigned from 716 to 757. For the first few years of his reign he had to face two strong rival kings, Wihtred of Kent and Ine of Wessex. But when Wihtred died in 725, and Ine abdicated in 726 to become a monk in Rome, Æthelbald was free to establish Mercia's hegemony over the rest of the Anglo-Saxons south of the Humber. Æthelbald suffered a setback in 752, when the West Saxons under Cuthred defeated him, but he seems to have restored his supremacy over Wessex by 757.[13]

In July 2009, the Staffordshire Hoard of Anglo-Saxon gold was discovered by Terry Herbert in a field near Lichfield in Staffordshire.[14] Lichfield functioned as the religious centre of Mercia. The artefacts have tentatively been dated by Svante Fischer and Jean Soulat to around AD 600–800.[15] Whether the hoard was deposited by Anglo-Saxon pagans or Christians remains unclear, as does the purpose of the deposit.[16]

Reign of Offa and rise of Wessex

After the murder of Æthelbald by one of his bodyguards in 757, a civil war broke out which concluded with the victory of Offa, a descendant of Pybba. Offa (reigned 757 to 796) had to build anew the hegemony which his predecessor had exercised over the southern English, and he did this so successfully that he became the greatest king Mercia had ever known. Not only did he win battles and dominate Southern England, but also he took an active hand in administering the affairs of his kingdom, founding market towns and overseeing the first major issues of gold coins in Britain; he assumed a role in the administration of the Catholic Church in England (sponsoring the short-lived archbishopric of Lichfield, 787 to 799), and even negotiated with Charlemagne as an equal. Offa is credited with the construction of Offa's Dyke, which marked the border between Wales and Mercia.[17]

Offa exerted himself to ensure that his son Ecgfrith of Mercia would succeed him, but after Offa's death in July 796 Ecgfrith survived for only five months, and the kingdom passed to a distant relative named Coenwulf in December 796. In 821 Coenwulf's brother Ceolwulf succeeded to the Mercian kingship; he demonstrated his military prowess by his attack on and destruction of the fortress of Deganwy in Gwynedd. The power of the West Saxons under Egbert (King of Wessex from 802 to 839) grew during this period, however, and in 825 Egbert defeated the Mercian king Beornwulf (who had overthrown Ceolwulf in 823) at Ellendun.[18]

The Battle of Ellendun proved decisive. Beornwulf was slain while suppressing a revolt amongst the East Angles, and his successor, a former ealdorman named Ludeca (reigned 826–827), met the same fate. Another ealdorman, Wiglaf, subsequently ruled for less than two years before Egbert of Wessex drove him out of Mercia. In 830 Wiglaf regained independence for Mercia, but by this time Wessex had clearly become the dominant power in England. Circa 840 Beorhtwulf succeeded Wiglaf.[19]

Arrival of the Danes

In 852 Burgred came to the throne, and with Ethelwulf of Wessex subjugated North Wales. In 868 Danish invaders occupied Nottingham. The Danes drove Burgred from his kingdom in 874 and Ceolwulf II took his place. In 877 the Danes seized the eastern part of Mercia, which became part of the Danelaw.[21] Ceolwulf, the last king of Mercia, left with the western half, reigned until 879.[22] From about 883 until his death in 911 Æthelred, Lord of the Mercians, ruled Mercia under the overlordship of Wessex. All coins struck in Mercia after the disappearance of Ceolwulf in c. 879 were in the name of the West Saxon king.[23] Æthelred had married Æthelflæd (c. 870 – 12 June 918), daughter of Alfred the Great of Wessex (r. 871–899), and she assumed power when her husband became ill at some time in the last ten years of his life.[24]

After Æthelred's death in 911 Æthelflæd ruled as "Lady of the Mercians", but Alfred's successor as King of the Anglo-Saxons, Edward the Elder (r. 899–924), took control of London and Oxford, which Alfred had placed under Æthelred's control. Æthelflæd and her brother continued Alfred's policy of building fortified burhs, and in 917–918 they succeeded in conquering the southern Danelaw in East Anglia and Danish Mercia.[24]

In 2015, two individuals found a large hoard near Leominster consisting primarily of Saxon jewellery and silver ingots but also coins; the latter date to around 879 CE. According to a news report, "experts believe it [the hoard] was buried by a Viking during a series of raids known to have taken place in the area at that time", while Wessex was ruled by Alfred the Great and Mercia by Ceolwulf II. Two imperial coins recovered from the treasure hunters depict the two kings, "indicating an alliance between the two kingdoms—at least, for a time—that was previously unknown to historians", according to the report.[25][26] A report by The Guardian adds an additional perspective, suggesting that the coins "rewrite Anglo-Saxon history":[27]

"The presence of both kings on the two emperor coins suggests some sort of pact between the pair. But the rarity of the coins also suggests that Alfred quickly dropped his ally, who was just about written out of history".

Loss of independence

When Æthelflæd died in 918, Ælfwynn, her daughter by Æthelred, succeeded as 'Second Lady of the Mercians', but within six months Edward had deprived her of all authority in Mercia and taken her into Wessex.[24]

References to Mercia and the Mercians continue through the annals recording the reigns of Æthelstan and his successors. Æthelstan himself was raised in Mercia and became its king before he was king of Wessex. In Winchester, there was even an attempt to blind Æthelstan as he was seen as an outsider. In 975, King Edgar is described as “friend of the West Saxons and protector of the Mercians”.[28]

A separate political existence from Wessex was briefly restored in 955–959, when Edgar became king of Mercia, and again in 1016, when the kingdom was divided between Cnut and Edmund Ironside, Cnut taking Mercia.[29]

The last reference to Mercia by name is in the annal for 1017, when Eadric Streona was awarded the government of Mercia by Cnut. The later earls, Leofric, Ælfgar and Edwin, ruled over a territory broadly corresponding to historic Mercia, but the Chronicle does not identify it by name. The Mercians as a people are last mentioned in the annal for 1049.[30]

Mercian dialect

The dialect thrived between the 8th and 13th centuries and was referred to by John Trevisa, writing in 1387:[31]

For men of the est with men of the west, as it were undir the same partie of hevene, acordeth more in sownynge of speche than men of the north with men of the south, therfore it is that Mercii, that beeth men of myddel Engelond, as it were parteners of the endes, understondeth better the side langages, northerne and southerne, than northerne and southerne understondeth either other...

J. R. R. Tolkien is one of many scholars who have studied and promoted the Mercian dialect of Old English, and introduced various Mercian terms into his legendarium – especially in relation to the Kingdom of Rohan, otherwise known as the Mark (a name cognate with Mercia). Not only is the language of Rohan actually represented as[32] the Mercian dialect of Old English, but a number of its kings are given the same names as monarchs who appear in the Mercian royal genealogy, e.g., Fréawine, Fréaláf and Éomer (see List of kings of the Angles).[33]

Mercian religion

The first kings of Mercia were pagans, and they resisted the encroachment of Christianity longer than other kingdoms in the Anglo-Saxon Heptarchy.[34]

Mercian rulers remained resolutely pagan until the reign of Peada in 656, although this did not prevent them joining coalitions with Christian Welsh rulers to resist Northumbria. The first appearance of Christianity in Mercia, however, had come at least thirty years earlier, following the Battle of Cirencester of 628, when Penda incorporated the formerly West Saxon territories of Hwicce into his kingdom.[35]

The conversion of Mercia to Christianity occurred in the latter part of the 7th century, and by the time of Penda's defeat and death, Mercia was largely surrounded by Christian states. Diuma, an Irish monk and one of Oswiu's missionaries, was subsequently ordained a bishop – the first to operate in Mercia. Christianity finally gained a foothold in Mercia when Oswiu supported Peada as sub-king of the Middle Angles, requiring him to marry Oswiu's daughter, Alchflaed, and to accept her religion.[36]

Decisive steps to Christianise Mercia were taken by Chad (Latinised by Bede as Ceadda), the fifth[37] bishop to operate in Mercia. This controversial figure was given land by King Wulfhere to build a monastery at Lichfield. Evidence suggests that the Lichfield Gospels were made in Lichfield around 730. As in other Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, the many small monasteries established by the Mercian kings allowed the political/military and ecclesiastical leadership to consolidate their unity through bonds of kinship.[38]

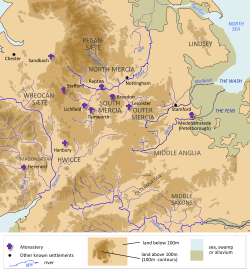

Subdivisions of Mercia

For knowledge of the internal composition of the Kingdom of Mercia, we must rely on a document of uncertain age (possibly late 7th century), known as the Tribal Hidage – an assessment of the extent (but not the location) of land owned (reckoned in hides), and therefore the military obligations and perhaps taxes due, by each of the Mercian tribes and subject kingdoms by name. This hidage exists in several manuscript versions, some as late as the 14th century. It lists a number of peoples, such as the Hwicce, who have now vanished, except for reminders in various placenames. The major subdivisions of Mercia were as follows:[39]

- South Mercians

- The Mercians dwelling south of the River Trent. Folk groups within included the Tomsæte around Tamworth and the Pencersæte around Penkridge (approx. S. Staffs. & N. Warks.).

- North Mercians

- The Mercians dwelling north of the River Trent (approx. E. Staffs., Derbys. & Notts.).

- Outer Mercia

- An early phase of Mercian expansion, possibly 6th century (approx. S. Lincs., Leics., Rutland, Northants. & N. Oxon.).

- Once a kingdom in its own right, disputed with Northumbria in the 7th century before finally coming under Mercian control (approx. N. Lincs.).

- A collection of many smaller folk groups under Mercian control from the 7th century, including the Spaldingas around Spalding, the Bilmingas and Wideringas near Stamford, the North Gyrwe and South Gyrwe near Peterborough, the West Wixna, East Wixna, West Wille and East Wille near Ely, the Sweordora, Hurstingas and Gifle near Bedford, the Hicce around Hitchin, the Cilternsæte in the Chilterns and the Feppingas near Thame (approx. Cambs., Beds., Herts., Bucks. & S. Oxon.).

- Once a kingdom in its own right, disputed with Wessex in the 7th century before finally coming under Mercian control. Smaller folk groups within included the Stoppingas around Warwick and the Arosæte near Droitwich (approx. Gloucs., Worcs. & S. Warks.).

- A people of the Welsh border, also known as the Westerna, under Mercian control from the 7th century. Smaller folk groups within included the Temersæte near Hereford and the Hahlsæte near Ludlow (approx. Herefs. & S. Shrops.).

- A people of the Welsh border under Mercian control from the 7th century. Smaller folk groups within included the Rhiwsæte near Wroxeter and the Meresæte near Chester (approx. N. Shrops., Flints. & Cheshire).

- An isolated folk group of the Peak District, under Mercian control from the 7th century (approx. N. Derbys.).

- A disorganised region under Mercian control from the 7th century (approx. Merseyside, Greater Manchester).

- Taken over from Essex in the 8th century, including London (approx. Greater London, Hertfordshire, Surrey).

After Mercia was annexed by Wessex in the early 10th century, the West Saxon rulers divided it into shires modelled after their own system, cutting across traditional Mercian divisions. These shires survived mostly intact until 1974, and even today still largely follow their original boundaries.

Legacy

Modern uses of the name Mercia

The term "midlands" is first recorded (as mydlande) in 1555.[40] It is possible, therefore, that until then Mercia had remained the preferred term, as the quote from Trevisa above would indicate.[31]

John Bateman, writing in 1876 or 1883, referred to contemporary Cheshire and Staffordshire landholdings as being in Mercia.[41] The most credible source for the idea of a contemporary Mercia is Thomas Hardy's Wessex novels. The first of these appeared in 1874 and Hardy himself considered it the origin of the conceit of a contemporary Wessex. Bram Stoker set his 1911 novel The Lair of the White Worm in a contemporary Mercia that may have been influenced by Hardy, whose secretary was a friend of Stoker's brother. Although 'Edwardian Mercia' never had the success of 'Victorian Wessex', it was an idea that appealed to the higher echelons of society. In 1908 Sir Oliver Lodge, Principal of Birmingham University, wrote to his counterpart at Bristol, welcoming a new university worthy of "...the great Province of Wessex whose higher educational needs it will supply. It will be no rival, but colleague and co-worker with this university, whose province is Mercia...".[42]

The British Army has made use of several regional identities in naming larger, amalgamated formations. After the Second World War, the infantry regiments of Cheshire, Staffordshire and Worcestershire were organised in the Mercian Brigade (1948–1968). Today, "Mercia" appears in the titles of two regiments, the Mercian Regiment, founded in 2007, which recruits in Cheshire, Derbyshire, Nottinghamshire, Worcestershire, and parts of Greater Manchester and the West Midlands, and the Royal Mercian and Lancastrian Yeomanry, founded in 1992 as part of the Territorial Army. The police forces of Herefordshire, Shropshire and Worcestershire were combined into the West Mercia Constabulary in 1967.[43]

Telephone directories across the Midlands include a large number of commercial and voluntary organisations using "Mercia" in their names, and in 2012 a new football league was formed called the Mercian Regional Football League.[44]

The Acting Witan of Mercia, previously known as the Mercian Constitutional Convention, is a radical political organisation that claims to be the legal government of Mercia, having declared independence from the United Kingdom on 29 May 2003 in Victoria Square, Birmingham.[45][46][47][48]

Symbolism and attributed heraldry

There is no authentic indigenous Mercian heraldic device, as heraldry did not develop in any recognizable form until the High Middle Ages.[49]

The saltire as a symbol of Mercia may have been in use since the time of King Offa.[50] By the 13th century, the saltire had become the attributed arms of the Kingdom of Mercia.[51] The arms are blazoned Azure, a saltire Or, meaning a gold (or yellow) saltire on a blue field. The arms were subsequently used by the Abbey of St Albans, founded by King Offa of Mercia. With the dissolution of the Abbey and the incorporation of the borough of St Albans the device was used on the town's corporate seal and was officially recorded as the arms of the town at an heraldic visitation in 1634.[52]

The saltire is used as both a flag and a coat of arms. As a flag, it is flown from Tamworth Castle, the ancient seat of the Mercian Kings, to this day.[50] The flag also appears on street signs welcoming people to Tamworth, the "ancient capital of Mercia". It was also flown outside Birmingham Council House during 2009 while the Staffordshire Hoard was on display in the city before being taken to the British Museum in London. The cross has been incorporated into a number of coats of arms of Mercian towns, including Tamworth, Leek and Blaby. It was recognised as the Mercian flag by the Flag Institute in 2014.[53]

The silver double-headed eagle surmounted by a golden three-pronged Saxon crown has been used by several units of the British Army as a heraldic device for Mercia since 1958, including the Mercian Regiment. It is derived from the attributed arms of Leofric, Earl of Mercia in the 11th century.[54] It is worth noting, however, that Leofric is sometimes attributed a black, single-headed eagle instead.[55]

The wyvern, a type of dragon, came to have a strong association with Mercia in the 19th century. The Midland Railway, which used a white (silver) wyvern sans legs (legless) as its crest, having inherited it from the Leicester and Swannington Railway, asserted that the "wyvern was the standard of the Kingdom of Mercia", and that it was "a quartering in the town arms of Leicester".[56] The symbol appeared on numerous stations and other company buildings in the region, and was worn as a silver badge by all uniformed employees. However, in 1897 the Railway Magazine noted that there appeared "to be no foundation that the wyvern was associated with the Kingdom of Mercia".[57] It has been associated with Leicester since the time of Thomas, 2nd Earl of Lancaster and Leicester (c. 1278–1322), the most powerful lord in the Midlands, who used it as his personal crest, and was recorded in a heraldic visitation of the town in 1619.[58]

In Bram Stoker's 1911 novel The Lair of the White Worm, explicitly set in Mercia (see above), the Mercian white wyvern sans legs of the Midland Railway was transformed into a monstrous beast, the eponymous worm of the title. The word "worm" is derived from Old English wyrm and originally referred to a dragon or serpent. "Wyvern" derives from Old Saxon wivere, also meaning serpent, and is etymologically related to viper. Today, the White Wyrm of Mercia is recognised as the Mercian flag by the Acting Witan of Mercia.[59]

The ultimate source for the symbolism of white dragons in England would appear to be Geoffrey of Monmouth’s fictional work, The History of the Kings of Britain (c. 1136), which recounts an incident in the life of Merlin where a red dragon is seen fighting a white dragon and prevailing. The red dragon was taken to represent the Welsh and their eventual victory over the Anglo-Saxon invaders, symbolised by the white dragon.[60]

Professor Tom Shippey has suggested that the Middle Kingdom in J. R. R. Tolkien's Farmer Giles of Ham, a story dominated by a dragon, is based on Mercia. This dragon, Chrysophylax, though mostly hostile, eventually helps Giles found a realm of his own, the Little Kingdom.[61]

See also

References

- Roach & Hartman, eds. (1997) English Pronouncing Dictionary, 15th edition. (Cambridge University Press). p. 316; see also J.C. Wells, Longman Pronunciation Dictionary and Upton et al., Oxford Dictionary of Pronunciation for Current English.

- "Mercia | historical kingdom, England". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 28 December 2018.

-

- Brooks, N. (1989). "The formation of the Mercian kingdom". In Bassett, Steven (ed.). The Origins of Anglo-Saxon Kingdoms. Leicester. p. 159.

- Stenton, F. M. (1970). "The Supremacy of the Mercian kings". In Stenton, D. M. (ed.). Preparatory to Anglo-Saxon England. Oxford. pp. 48–66.

- Fouracre (2005), p. 466

- Blair 1948, p. 119-121

- Brooks, Nicholas. Anglo-Saxon myths: state and church, 400–1066.

Hill, D. (1981). Atlas of Anglo-Saxon England. Oxford. map 136.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Hooke, Della (1986). Anglo-Saxon Territorial Organisation: The Western Margins of Mercia. Occasional Paper 22. University of Birmingham, Dept. of Geography. pp. 1–45. - Kessler, P L. "Kingdoms of the Anglo-Saxons - Iclingas & Mercians". www.historyfiles.co.uk. Retrieved 25 September 2018.

- Starr, Brian Daniel (2007). Ancestral Secrets of Knighthood. BookSurge Publishing. p. 135. ISBN 978-1419680120.

- Jolliffe, J. E. A. The Constitutional History of Medieval England from the English Settlement to 1485 London 1961 p.32

- Fouracre (2005), p. 465

- Evans and Fulton, p. 41

- Sharon Turner, The history of the Anglo-Saxons from the earliest period to the Norman conquest, Volume 1 (Philadelphia: Carey & Hart, 1841), p. 267

- Leahy, Kevin; Bland, Roger (2009). The Staffordshire Hoard, British Museum Press, pp. 4, 6

- Svante Fischer and Jean Soulat, The Typochronology of Sword Pommels from the Staffordshire Hoard, The Staffordshire Hoard Symposium (March 2010).

- "Huge Anglo-Saxon gold hoard found". News.bbc.co.uk. 24 September 2009. Retrieved 24 September 2009.

- Davies, John (2007) [1993]. A History of Wales. London: Penguin. pp. 65–66.

- Camden, William (1610). "A Chronological description of the most flourishing Kingdomes, England, Scotland, and Ireland". London: George Bishop and John Norton.

- Zaluckyj & Feryok, "Decline", pp. 238–239.

- Falkus & Gillingham (1989), p. 52; Hill (1981)

- Frank Stenton, Anglo-Saxon England, Oxford University Press, 1971, p. 254

- Miller, Sean (2004). "Ceolwulf II (fl. 874–879), king of the Mercians". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/39145. Retrieved 7 August 2012. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- Stewart Lyon, The coinage of Edward the Elder, in N. J. Higham & D.H. Hill, Edward the Elder 899–924, London 2001, p. 67.

- Costambeys, Marios (2004). "Æthelflæd (Ethelfleda) (d. 918), ruler of the Mercians". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/8907. Retrieved 7 August 2012. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- "Millions of dollars of Viking treasure that could rewrite history stolen, metal detectorists convicted". Newsweek. 22 November 2019. Retrieved 24 November 2019.

An example of a rare two emperor coin, hinting at a previously-unknown alliance between the kingdoms of Wessex and Mercia.

- "Detectorists stole Viking hoard that 'rewrites history'". BBC News. 21 November 2019. Retrieved 24 November 2019.

"These coins enable us to re-interpret our history at a key moment in the creation of England as a single kingdom," according to Gareth Williams, curator of early medieval coins at the British Museum.

- "Detectorists stole Viking hoard that 'rewrites history'". The Guardian. 21 November 2019. Retrieved 24 November 2019.

- Smith, Lesley M. (1984). The Making of Britain: The Dark Ages. Palgrave. p. 122. ISBN 978-0333375143.

- "Knut's Invasion of England in 1015-16, according to the Knytlinga Saga". De Re Militari. Archived from the original on 26 September 2011. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- Swanton, Michael (2000). The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. Phoenix Press. p. 168. ISBN 978-1842120033.

- Elmes (2005)

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (2005). The Lord of the Rings. Houghton-Mifflin. pp. 1133–1138. ISBN 978-0-618-64561-9. For more on Tolkien’s "translation" of the language of Rohan into Old English, see especially page 1136.

- Shippey, Prof. Tom (2005). The Road to Middle Earth. HarperCollins. pp. 139–140. ISBN 0-261-10275-3. Shippey notes that Tolkien uses 'Mercian' forms of Anglo-Saxon, e.g., "Saruman, Hasufel, Herugrim for 'standard' [Anglo-Saxon] Searuman, Heasufel and Heorugrim" Footnote page 140

- Bede. Ecclesiastical History of the English People. pp. Book 3, chapter 21.

- Bradbury, Jim (2004). The Routledge Companion to Medieval Warfare. Routledge. p. 137. ISBN 978-0415221269.

- Bede. Ecclesiastical History of the English People. Book 3, chapter 21.

- Bede. Ecclesiastical History of the English People. Book 3, chapter 24.

- Fletcher, Richard (1997). The Conversion of Europe. HarperCollins. pp. 172–174, 181–182. ISBN 0-00-255203-5.

- Zaluckyj & Feryok (2001)

- McWhirter (1976)

- Bateman (1971)

- Cottle & Sherborne (1951)

- "Police Records". Shropshire Archives. Retrieved 21 May 2020.

- "The Sportsjam Regional Football League". The Football Association. n.d. Archived from the original on 26 November 2015. Retrieved 26 November 2015.

- Smith, David M.; Wistrich, Enid (2015). Devolution and Localism in England. Ashgate. p. 33.

- Childs, Simon; Francey, Matthew (23 February 2013). "We asked the lunatic fringe of UK politics about their ideal Britain". Vice. Archived from the original on 25 October 2015. Retrieved 5 July 2016.

- "Give Midlands an independence vote like Scotland's, urges Acting Witan of Mercia". 10 September 2014.

- "'Hoard belongs to Mercian kingdom'". 27 February 2010.

- Fox-Davies (1909), pp. 1–18

- "Photo-gallery: Saxon trail across Mercian Staffordshire". BBC News. 7 April 2011.

- College of Arms Ms. L.14, dating from the reign of Henry III

- "Civic heraldry of England and Wales – Hertdordshire". www.civicheraldry.co.uk.

- Flag Institute: Mercia, St Alban's Cross.

- A.L. Kipling and H.L. King, Head-dress Badges of the British Army, Vol. 2, reprinted, Uckfield, 2006

- "Heraldry of the world - Coventry". www.ngw.nl. Archived from the original on 28 June 2008. Retrieved 17 May 2008.

- Geoffrey Briggs, Civic & Corporate Heraldry, London 1971

C. W. Scot-Giles, Civic Heraldry of England and Wales, 2nd edition, London, 1953

A. C. Fox-Davies, The Book of Public Arms, London 1915

Cuthbert Hamilton Ellis, The Midland Railway, 1953

Frederick Smeeton Williams, The Midland Railway: Its rise and progress: A narrative of modern enterprise, 1876

The Railway Magazine, Vol. 102, 1897

Dow (1973)

Clement Edwin Stretton, History of The Midland Railway, 1901 - The Railway Magazine, Vol. 102, 1897

- Leicestershire History: What is the Origin of the Leicester Wyvern?

- Independent Mercia: Declaration of Independence

- Monmouth, Geoffrey of (1973). The History of the Kings of Britain. Penguin. ISBN 978-0140441703.

- Shippey, Prof. Tom, The Road to Middle-earth, revised edition (2003), Houghton Mifflin, p.98, ISBN 0-618-25760-8

Further reading

- Bateman, John (1971). The Great Landowners of Great Britain and Ireland. Leicester University Press. ISBN 0-391-00157-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Baxter, Stephen (2007). The earls of Mercia: lordship and power in late Anglo-Saxon England. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-923098-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Blair, Peter Hunter (1948). The Northumbrians and their Southern Frontier. Archaeologia Aeliana, 4th series 26. pp. 98–126.

- Brown, Michelle; Farr, Carol, eds. (2005). Mercia: An Anglo-Saxon Kingdom in Europe. ISBN 0-8264-7765-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cottle, Basil; Sherborne, J.W. (1951). The Life of a University. University of Bristol. OCLC 490908616.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dow, George (1973). Railway Heraldry: and other insignia. Newton Abbot: David and Charles. ISBN 9780715358962.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Elmes, Simon (2005). Talking for Britain: A Journey Through the Nation’s Dialects. Penguin. ISBN 0-14-051562-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Evans, Geraint; Fulton, Helen (2019). The Cambridge History of Welsh Literature. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1107106765.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Falkus, Malcolm; Gillingham, John (1989). Historical Atlas of Britain. Kingfisher. ISBN 0-86272-295-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fox-Davies, Arthur Charles (1909). A Complete Guide to Heraldry. London: T.C. & E.C. Jack. LCCN 09023803 – via Internet Archive.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fouracre, Paul, ed. (2005). The New Cambridge Medieval History. c.500 - c.700. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521362917.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gelling, Margaret (1989). "The Early History of Western Mercia". In Bassett, S. (ed.). The Origins of the Anglo-Saxon Kingdoms. pp. 184–201. ISBN 9780718513177.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- McWhirter, Norris (1976). The Guinness Book of Answers. Enfield: Guinness Superlatives Ltd. ISBN 0-900424-35-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Schama, Simon (2003). A History of Britain. At the edge of the world?: 3000 BC-AD 1603. BBC Books. ISBN 9780563487142.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Walker, Ian W. (2000). Mercia and the Making of England. ISBN 0-7509-2131-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)—also published as Mercia and the Origins of England. 2000. ISBN 0-7509-2131-5.

- Zaluckyj, Sarah; Feryok, Marge (2001). Mercia: The Anglo-Saxon Kingdom of Central England. ISBN 1-873827-62-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

.svg.png)