Aberdare

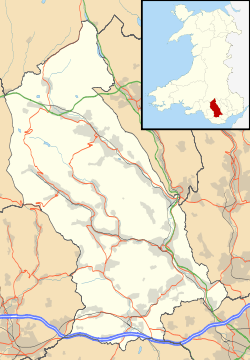

Aberdare (/ˌæbərˈdɛər/ ab-ər-DAIR;[2] Welsh: Aberdâr) is a town in the Cynon Valley area of Rhondda Cynon Taf, Wales, at the confluence of the Rivers Dare (Dâr) and Cynon. Aberdare has a population of 39550(mid-2017 estimate).[3] Aberdare is 4 miles (6 km) south-west of Merthyr Tydfil, 20 miles (32 km) north-west of Cardiff and 22 miles (35 km) east-north-east of Swansea. During the 19th century it became a thriving industrial settlement, which was also notable for the vitality of its cultural life and as an important publishing centre.

Aberdare

| |

|---|---|

| |

Aberdare Location within Rhondda Cynon Taf | |

| Population | 39,550 (Mid-2017 Estimate)[1] |

| OS grid reference | SO005025 |

| Principal area | |

| Ceremonial county | |

| Country | Wales |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | ABERDARE |

| Postcode district | CF44 |

| Dialling code | 01685 |

| Police | South Wales |

| Fire | South Wales |

| Ambulance | Welsh |

| UK Parliament | |

| Senedd Cymru – Welsh Parliament |

|

History

The settlement of Aberdare dates from at least the Middle Ages, with the first known reference being in a monastic chapter of 1203 concerning grazing right on Hirwaun Common.[4] It was originally a small village in an agricultural district, centred around the Church of St John the Baptist, said to date from 1189. By the middle of the 15th century, Aberdare contained a water mill in addition to a number of thatched cottages, of which no evidence remains.[5] In the early 19th century the population of Aberdare grew rapidly, owing to the abundance of coal and iron ore,: the population of the whole parish, 1,486 in 1801, increased tenfold during the first half of the 19th century.[6]

Two major industries supported the growth of the community: first iron, then coal. A branch of the Glamorganshire Canal (1811) was used to transport these products; then the railway became the main means of transport to the South Wales coast.[7] From the 1870s onwards, the economy of the town was dominated by the coal mining industry, with only a small tinplate works. There were also several brickworks and breweries. During the latter half of the 19th century, considerable improvements were made to the town, which became a pleasant place to live, despite the nearby collieries. A postgraduate theological college opened in connection with the Church of England in 1892, but in 1907 it moved to Llandaff.[6]

With the ecclesiastical parishes of St Fagan's (Trecynon) and Aberaman carved out of the ancient parish, Aberdare had 12 Anglican churches and one Catholic church, built in 1866 in Monk Street near the site of a cell attached to Penrhys monastery; and at one time there were over 50 Nonconformist chapels (including those in surrounding settlements such as Cwmaman and Llwydcoed). The services in the majority of the chapels were in Welsh. Most of these chapels have now closed, with many converted to other uses. The urban district includes what were once the separate villages of Aberaman, Abernant, Cwmaman, Cwmbach, Cwmdare, Llwydcoed, Penywaun and Trecynon. There are several cairns and the remains of a circular British encampment on the mountain between Aberdare and Merthyr. Hirwaun moor, 4 miles to the north west of Aberdare, was according to tradition the scene of a battle at which Rhys ap Tewdwr, prince of Dyfed, was defeated by the allied forces of the Norman Robert Fitzhamon and Iestyn ap Gwrgant, the last Welsh prince of Glamorgan.[6]

Population growth

The parish population was 1,486 in 1801, but expanded fast, especially during the 1840s and 1850s: the population of the Aberdare District, centred on the town, was 9,322 in 1841; 18,774 in 1851; and 37,487 in 1861. This population growth, a result of the growth of the steam coal trade (see below) was increasingly concentrated in the previously agricultural areas of Blaengwawr and Cefnpennar to the south of the town. Many of the migrants came from the rural parts of west Wales which had been affected by an agricultural depression.[8] Population levels continued to increase over the next forty years, albeit with a small decline in the 1870s. The first decade of the 20th century saw a further sharp increase, largely as a result of the steam coal trade, reaching 53,779 in 1911.[9] The population has since declined owing to the loss of most of the heavy industry.

The Aberdare population at the 2001 census was 31,705 (ranked 13th largest in Wales).[10] By 2011 it was 29,748, though the figure includes the surrounding populations of Aberaman, Abercwmboi, Cwmbach and Llwydcoed.[11]

21st century

On 1 December 2016, following The Rhondda Cynon Taf (Communities) Order 2016, the community of Aberdare was split into two new communities, Aberdare East and Aberdare West.[12] These are coterminous with the electoral wards of the same names. Aberdare East includes Aberdare town centre and the village of Abernant. Aberdare West includes Cwmdare, Cwm Sian and Trecynon.

Language

Welsh was the prominent language until the mid 20th century and Aberdare was an important centre of Welsh language publishing. A large proportion of the early migrant population were Welsh speaking, and in 1851 only ten per cent of the population had been born outside of Wales.[13]

In his controversial evidence to the 1847 Education Reports (known in Wales as the Brad y Llyfrau Gleision or Treachery of the Blue Books), the Anglican vicar of Aberdare, John Griffith, stated that the English language was "generally understood" and referred to the arrival of people from anglicised areas such as Radnorshire and south Pembrokeshire.[14] Griffith also made allegations about the Welsh speaking population and what he considered to be the degraded character of the women of Aberdare, alleging sexual promiscuity was an accepted social convention, that drunkenness and improvidence amongst the miners was common and attacking what he saw as exaggerated emotion in the religious practices of the Nonconformists.[15]

This evidence helped inform the findings of the report which would go on to stigmatise Welsh people as "ignorant", "lazy" and "immoral" and found the reason for this was the continued use of the Welsh language, which it described as "evil". The controversial reports allowed the local non-conformist minister Thomas Price of Calfaria to arrange public meetings, from which he would emerge as a leading critic of the vicar's evidence and, by implication, a defender of both the Welsh language and the morality of the local population,[16] It is still contended that Griffiths was made vicar of Merthyr in the neighbouring valley to escape local anger,[17] even though it was over ten years before he left Aberdare. The reports and subsequent defence would maintain the perceptions of Aberdare, the Cynon Valley and even the wider area as proudly nonconformist and defiantly Welsh speaking throughout its industrialised history.[18]

By 1901, the census recorded that 71.5% of the population of Aberdare Urban District spoke Welsh, but this fell to 65.2% in 1911.[19] The 1911 data shows that Welsh was more widely spoken among the older generation compared to the young, and amongst women compared to men. A shift in language was expedited with the loss of men during the First World War and the resulting economic turmoil.[20] English gradually began to replace Welsh as the community language, as shown by the decline of the Welsh language press in the town. This pattern continued after the Second World War despite the advent of Welsh medium education. Ysgol Gymraeg Aberdâr, the Welsh-medium primary school, was established in the 1950s with Idwal Rees as head teacher.

According to the 2011 Census, 97.7% of Aberdare residents aged three years and over can speak Welsh, with 24.8% of 3–15-year olds stating that they can speak it.[21]

Industry

Iron Industry

Ironworks were established at Llwydcoed and Abernant in 1799[7] and 1800 respectively, followed by others at Gadlys and Aberaman in 1827 and 1847. The iron industry began to expand in a significant way around 1818 when the Crawshay family of Merthyr purchased the Hirwaun ironworks and place them under independent management. In the following year, Rowland Fothergill took over the ironworks at Abernant and a few years later did the same at Llwydcoed. Both concerns later fell into the hands of his nephew Richard Fothergill. The Gadlys Ironworks was established in 1827 by Matthew Wayne, who had previously managed the Cyfarthfa ironworks at Merthyr.[22] The Gadlys works, now considered an important archaeological site, originally comprised four blast furnaces, inner forges, rowing mills and puddling furnaces. The development of these works provided impetus to the growth of Aberdare as a nucleated town.[5] The iron industry was gradually superseded by coal and all the five iron works had closed by 1875, as the local supply of iron ore was inadequate to meet the ever-increasing demand created by the invention of steel, and as a result the importing of ore proved more profitable.[5]

Coal industry

The iron industry had a relatively small impact upon the economy of Aberdare and in 1831 only 1.2% of the population was employed in manufacturing, as opposed to 19.8% in neighbouring Merthyr Tydfil.[22] In the early years of Aberdare's development, most of the coal worked in the parish was coking coal, and was consumed locally, chiefly in the ironworks.[6] Although the Gadlys works was small in comparison with the other ironworks it became significant as the Waynes also became involved in the production of sale coal.[23] In 1836, this activity led to the exploitation of the "Four-foot Seam" of high-calorific value steam coal began, and pits were sunk in rapid succession.

In 1840, Thomas Powell sank a pit at Cwmbach, and during the next few years he opened another four pits. In the next few years, other local entrepreneurs now became involved in the expansion of the coal trade, including David Williams at Ynysgynon and David Davis at Blaengwawr, as well as the latter's son David Davis, Maesyffynnon. They were joined by newcomers such as Crawshay Bailey at Aberaman and, in due course, George Elliot in the lower part of the valley.[24] This coal was valuable for steam railways and steam ships, and an export trade began,[7] via the Taff Vale Railway and the port of Cardiff. The population of the parish rose from 6,471 in 1841 to 14,999 in 1851 and 32,299 in 1861 and John Davies[25] described it as "the most dynamic place in Wales". In 1851, the Admiralty decided to use Welsh steam coal in ships of the Royal Navy, and this decision boosted the reputation of Aberdare's product and launched a huge international export market.[26] Coal mined in Aberdare parish rose from 177,000 long tons (180,000 t) in 1844 to 477,000 long tons (485,000 t) in 1850,[27] and the coal trade, which after 1875 was the chief support of the town, soon reached huge dimensions.

The growth of the coal trade inevitably led to a number of industrial disputes, some of which were local and others which affected the wider coalfield. Trade unionism began to appear in the Aberdare Valley at intervals from the 1830s onwards but the first significant manifestation occurred during the Aberdare Strike of 1857–8. The dispute was initiated by the depression in trade which followed the Crimean War and saw the local coal owners successfully impose a reduction in wages. The dispute did, however, witness an early manifestation of mass trade unionism amongst the miners of the valley and although unsuccessful the dispute saw the emergence of a stronger sense of solidarity amongst the miners.[28]

Steam coal was subsequently found in the Rhondda and further west, but many of the great companies of the Welsh coal industry's Gilded Age started operation in Aberdare and the lower Cynon Valley, including those of Samuel Thomas, David Davies and Sons, Nixon's Navigation and Powell Duffryn.[26]

During the early years of the twentieth century, the Aberdare valley became the focus of increased militancy among the mining workforce and an unofficial strike by 11,000 miners in the district from 20 October 1910 unyil 2 February 1911 attracted much attention at the time, although it was ultimately overshadowed by the Cambrian dispute in the neighbouring Rhondda valley which became synonymous with the so-called Tonypandy Riots.[29]

In common with the rest of the South Wales coalfield, Aberdare's coal industry commenced a long decline after World War I, and the last two deep mines still in operation in the 1960s were the small Aberaman and Fforchaman collieries, which closed in 1962 and 1965 respectively.

On 11 May 1919, an extensive fire broke out on Cardiff Street, Aberdare.

With the decline of both iron and coal, Aberdare has become reliant on commercial businesses as a major source of employment. Its industries include cable manufacture, smokeless fuels, and tourism.[7]

Government

As a small village in the upland valleys of Glamorgan, Aberdare did not play any significant part in political life until its development as an industrial settlement. It was part of the lordship of Miskin, and the ancient office of High Constable continued in ceremonial form until relatively recent times.

Parliamentary elections

In 1832, Aberdare was removed from the county of Glamorgan and became part of the parliamentary borough of Merthyr Tydfil. For much of the nineteenth century, the representation was initially controlled by the ironmasters of Merthyr, notably the Guest family. From 1852 until 1868 the seat was held by Henry Austen Bruce whose main industrial interests lay in the Aberdare valley. Bruce was a Liberal but was viewed with suspicion by the more radical faction which became increasingly influential within Welsh Liberalism in the 1860s. The radicals supported such policies as the disestablishment of the Church of England and were closely allied to the Liberation Society.

1868 general election

Nonconformist ministers played a prominent role in this new politics and, at Aberdare, they found an effective spokesman in the Rev Thomas Price minister of Calfaria, Aberdare. Following the granting of a second parliamentary seat to the borough of Merthyr Tydfil in 1867, the Liberals of Aberdare sought to ensure that a candidate from their part of the constituency was returned alongside the sitting member, Henry Austen Bruce. Their choice fell upon Richard Fothergill, owner of the ironworks at Abernant, who was enthusiastically supported by the Rev Thomas Price. Shortly before the election, however, Henry Richard intervened as a radical Liberal candidate, invited by the radicals of Merthyr. To many people's surprise, Price was lukewarm about his candidature and continued to support Fothergill. Ultimately, Henry Richard won a celebrated victory with Fothergill in second place and Bruce losing his seat. Richard thus became one of the-first radical MPs from Wales.[30]

1874–1914

At the 1874 General Election, both Richard and Fothergill were again returned, although the former was criticised for his apparent lack of sympathy towards the miners during the industrial disputes of the early 1870s. This led to the emergence of Thomas Halliday as the first labour or working-class candidate to contest a Welsh constituency. Although he polled well, Halliday fell short of being elected. For the remainder of the nineteenth century, the constituency was represented by industrialists, most notably David Alfred Thomas. In 1900, however, Thomas was joined by Keir Hardie, the ILP candidate, who became the first labour representative to be returned for a Welsh constituency independent of the Liberal Party.

Twentieth century

The Aberdare constituency came into being at the 1918 election. The first representative was Charles Butt Stanton who had been elected at a by-election following Hardie's death in 1915. However, in 1922, Stanton was defeated by a Labour candidate and the party has held the seat ever since. The only significant challenge came from Plaid Cymru at the 1970 and February 1974 General Elections but this performance has not since been repeated. Since 1984 the parliamentary seat, now known as Cynon Valley has been held by Ann Clwyd.

Local government

Until the mid-nineteenth century the local government of Aberdare and its locality remained in the hands of traditional structures such as the parish vestry and the High Constable, who was chosen on an annual basis. However, the rapid industrial development of the parsing resulted in the situation where these traditional bodies could not cope with the realities of an urbanised, industrial community which had developed without any planning or facilities. During the early decades of the century the iron masters gradually imposed their influence over local affairs and this remained the case following the formation of the Merthyr Board of Guardians in 1836. During the 1850s and early 1860s, however, as coal displaced iron as the main industry in the valley, the ironmasters were displaced as the dominant group in local government and administration by an alliance between mostly indigenous coal owners, shopkeepers and tradesmen, professional men and dissenting ministers. A central figure in this development was the Rev Thomas Price. The growth of this alliance was rooted in the reaction to the 1847 Education Reports and the subsequent efforts to establish a British School at Aberdare.[31]

In the 1840s there were no adequate sanitary facilities or water supply and life expectancy was low. Outbreaks of cholera and typhus were commonplace.[32] Against this background, Thomas Webster Rammell prepared a report for the General Board of Health on the sanitary condition of the parish, which concluded that a Local Board of Health be established.[33] This happened in 1854. Its first chairman was Richard Fothergill and the members included David Davis, Blaengwawr, David Williams (Alaw Goch), Rees Hopkin Rhys and the Rev. Thomas Price.[34] It was followed by the Aberdare School Board in 1871.

By 1889, the Local Board of Health had initiated a number of developments which included the purchase of local reservoirs from the Aberdare Waterworks Company for £97,000, a sewerage scheme costing £35,000, as well as the opening of Aberdare Public Park and a local fever hospital. The lack of a Free Library, however, remained a concern.[35]

Later, the formation of the Glamorgan County Council (upon which Aberdare had five elected members) in 1889, followed by the Aberdare Urban District Council, which replaced the Local Board in 1889, transformed the local politics of the Aberdare valley.

At the 1889 Glamorgan County Council Elections most of the elected representatives were coalowners and industrialists and the only exception in the earlier period was the miners' agent David Morgan (Dai o'r Nant), elected in 1892 as a labour representative. From the early 1900s, however, Labour candidates began to gain ground and dominated local government from the 1920s onwards. The same pattern was seen on the Aberdare UDC.

In 1974, following local government re-organization, Aberdare became part of the county of Mid Glamorgan and the Cynon Valley Borough Council. Labour members held a majority of seats on both authorities until their abolition in 1996. Since the latest re-organization, Aberdare has been part of the Rhondda Cynon Taff unitary authority. Once again, Labour has been the majority party although Plaid Cymru controlled the authority from 1999 until 2003.

Since 1995 Aberdare has elected county councillors to Rhondda Cynon Taf County Borough Council. The town lies mainly in the Aberdare East ward, represented by two county councillors. Nearby Cwmdare, Llwydcoed and Trecynon are represented by the Aberdare West/Llwydcoed ward. Both wards have been represented by the Labour Party since 2012.[36][37]

Culture

Aberdare, during its boom years, was considered a centre of Welsh culture: it hosted the first National Eisteddfod in 1861, with which David Williams (Alaw Goch) was closely associated. A number of local eisteddfodau had long been held in the locality, associated with figures such as William Williams (Carw Coch) The Eisteddfod was again held in Aberdare in 1885, and also in 1956 at Aberdare Park where the Gorsedd standing stones still exist. At the last National Eisteddfod held in Aberdare in 1956 Mathonwy Hughes won the chair. From the mid nineteenth century, Aberdare was an important publishing centre where a large number of books and journals were produced, the majority of which were in the Welsh language. A newspaper entitled Y Gwladgarwr (the Patriot) was published at Aberdare from 1856 until 1882 and was circulated widely throughout the South Wales valleys. From 1875 a more successful newspaper, Tarian y Gweithiwr (the Workman's Shield) was published at Aberdare by John Mills. Y Darian, as it was known, strongly supported the trade union movements among the miners and ironworkers of the valleys. The miners' leader, William Abraham, derived support from the newspaper, which was also aligned with radical nonconformist liberalism. The rise of the political labour movement and the subsequent decline of the Welsh language in the valleys, ultimately led to its decline and closure in 1934.

The Coliseum Theatre is Aberdare's main arts venue, containing a 600-seat auditorium and cinema. It is situated in nearby Trecynon and was built in 1938 using miners' subscriptions.

The Second World War poet Alun Lewis, was born near Aberdare in the village Cwmaman and there is a plaque commemorating him, including a quotation from his poem The Mountain over Aberdare.

The founding members of the rock band Stereophonics originated from the nearby village of Cwmaman. It is also the hometown of guitarist Mark Parry of Vancouver rock band The Manvils. Famed anarchist-punk band Crass played their last live show for striking miners in Aberdare during the UK miners' strike.

Griffith Rhys Jones − or Caradog as he was commonly known − was the Conductor of the famous 'Côr Mawr' of some 460 voices (the South Wales Choral Union), which twice won first prize at Crystal Palace choral competitions in London in the 1870s. He is depicted in the town's most prominent statue by sculptor Goscombe John, unveiled on Victoria Square in 1920.

Aberdare was culturally twinned with the German town of Ravensburg.

Religion

Anglican Church

The original parish church of St John the Baptist was originally built in 1189. Some of its original architecture is still intact.[7][38]

With the development of Aberdare as an industrial centre in the nineteenth century it became increasingly apparent that the ancient church was far too small to service the perceived spiritual needs of an urban community, particularly in view of the rapid growth of nonconformity from the 1830s onwards. Eventually, John Griffith, the rector of Aberdare undertook to raise funds to build a new church, leading to the rapid construction of St Elvan's Church in the town centre between 1851 and 1852.[39] This Church in Wales church still stands the heart of the parish of Aberdare and has had extensive work since its erection.[38] The church has a modern electrical, two-manual and pedal board pipe organ,[40] that is still used in services.

John Griffith, vicar of Aberdare, who built St Elvan's, transformed the role of the Anglican church in the valley by building a number of other churches, including St Fagan's, Trecynon. Other churches in the parish are St Luke's (Cwmdare), St James's (Llwydcoed) and St Matthew's Church (1891) (Abernant).[41]

In the parish of Aberaman and Cwmaman is St Margaret's Church, with an old, but beautiful, pipe organ with two manuals and a pedal board. Also in this parish is St Joseph's Church, Cwmaman. St Joseph's has recently undergone much recreational work, almost converting the church into a community centre. However, regular church services still take place. Here, there is a two-manual and pedal board electric organ, with speakers at the front and sides of the church.

In 1910 there were 34 Anglican churches in the Urban District of Aberdare. A survey of the attendance at places of worship on a particular Sunday in that year recorded that 17.8% of worshippers attended church services, with the remainder attending nonconformist chapels.[42]

Nonconformity

The Aberdare Valley was a stronghold of Nonconformity from the mid-nineteenth century until the inter-war years. In the aftermath of the 1847 Education Reports nonconformists became increasingly active in the political and educational life of Wales and in few places was this as prevalent as at Aberdare. The leading figure was Thomas Price, minister of Calfaria, Aberdare.

Aberdare was a major centre of the 1904–05 Religious Revival, which had begun at Loughor near Swansea. The revival aroused alarm among ministers for the revolutionary, even anarchistic, impact it had upon chapel congregations and denominational organisation. In particular, it was seen as drawing attention away from pulpit preaching and the role of the minister.[43] The local newspaper, the Aberdare Leader, regarded the revival with suspicion from the outset, objecting to the 'abnormal heat' which it engendered.[44] Trecynon was particularly affected by the revival, and the meetings held there were sais to have aroused more emotion and excitement than the more restrained meetings in Aberdare itself. The impact of the revival was significant in the short term, but in the longer term was fairly transient.

Once the immediate impact of the revival had faded, it was clear from the early twentieth century that there was a gradual decline in the influence of the chapels. This can be explained by several factors, including the rise of socialism and the process of linguistic change which saw the younger generation increasingly turn to the English language. There were also theological controversies such as that over the New Theology propounded by R.J. Campbell.[45]

Of the many chapels, few are still used for their original purpose and a number of closed since the turn of the millennium. Many have been converted for housing or other purposes (including one at Robertstown which has become a mosque), and others demolished. Among the notable chapels were Calfaria, Aberdare and Seion, Cwmaman (Baptist); Saron, Aberaman and Siloa, Aberdare (Independent); and Bethania, Aberdare (Calvinistic Methodist).

Independents

The earliest Welsh Independent, or Congregationalist chapel in the Aberdare area was Ebenezer, trecynon, although meetings had been held from the latter years of the eighteenth century in dwelling houses in the locality, for example at Hirwaun.[46] During the nineteenth century, the Independents showed the biggest increases in terms of places of worship: from two in 1837 to twenty-five (four of them being English causes), in 1897.[47] By 1910 there were 35 Independent chapels, with a total membership of 8,612.[42] Siloa Chapel was the largest of the Independent chapels in Aberdare and is one of the few that remain open today, having been 're-established' as a Welsh language chapel. The Independent ministers of nineteenth-century Aberdare included some powerful personalities but none had the kind of wider social authority which Thomas Price enjoyed amongst the Baptists.

Of the other Independent chapels in the valley Saron, in Davis Street, Aberaman, was used for regular services by a small group of members until 2011. For many years, these were held in a small side-room, and not the chapel itself. The chapel has a large vestry comprising rows of two-way-facing wooden benches and a stage, with a side entrance onto Beddoe Street and back entrance to Lewis Street. Although the building is not in good repair, the interior, including pulpit and balcony seating area (back & sides), was in good order but the chapel eventually closed due to the very small number of members remaining. In February 1999, Saron was made a Grade II Listed Building.[48]

Baptists

The Baptists were the most influential of the nonconformist denominations in Aberdare and their development was led by the Rev. Thomas Price who came to Aberdare in the early 1840s as minister of Calfaria Chapel.[49] In 1837 the Baptists had three chapels, but in 1897 there were twenty, seventeen of them being Welsh.[47] By 1910 the number of chapels had increased to 30, with a total membership of 7,422.[42] Most of these Baptist chapels were established under the influence of Thomas Price who encouraged members to establish branch chapels to attract migrants who flocked to the town and locality from rural Wales. The chapels came together for regular gatherings, including baptismal services which were held in the River Cynon[50] As a result, Price exerted an influence in the religious life of the locality which was far greater than that of any other minister.[51]

Calvinistic Methodists

By 1910 there were 24 Calvinistic Methodist chapels in the Aberdare Urban District with a total membership of 4,879.[42] The most prominent of these was Bethania, Aberdare, once the largest chapel in Aberdare. Derelict for many years, it was demolished in 2015. The Methodists were numerically powerful and while some of their ministers such as William James of Bethania served on the Aberdare School Board and other public bodies, their constitution militated against the sort of active political action which came more naturally to the Baptists and Independents.[52]

Other denominations

The other denominations were weaker, including the Wesleyan Methodists who had 14 places of worship by 1910.[42] There was also a significant Unitarian tradition in the valley and three places of worship by 1910.[42] Highland Place Unitarian Church celebrated its 150th anniversary in 2010,[53] with a number of lectures on its history and the history of Unitarianism in Wales taking place there. The church has a two-manual pipe organ with pedal board that is used to accompany all services. The current organist is Grace Jones, the sister of the former organist Jacob Jones. The connected schoolroom is used for post-service meetings and socialising.

Judaism

Seymour Street was once home to a synagogue which opened its doors in the late 1800s and which closed in 1957. The site now has a blue plaque.[54]

Education

The state of education in the parish was a cause for concern during the early industrial period as is illustrated by the reaction to the 1847 Education Reports. Initially, there was an outcry, led by the Rev Thomas Price against the comments made by the vicar of Aberdare in his submission to the commissioners. However, on closer reflection, the reports related the deficiencies of educational provision, not only in Aberdare itself but also in the communities of the valleys generally. In so doing they not only criticised the ironmasters for their failure to provide schools for workers' children but also the nonconformists for not establishing British Schools.[55] At the ten schools in Aberdare there was accommodation for only 1,317 children, a small proportion of the population. Largely as a result of these criticisms, the main nonconformist denominations worked together to establish a British School, known locally as Ysgol y Comin, which was opened in 1848, accommodating 200 pupils. Funds were raised which largely cleared the debts and the opening of the school was marked by a public meeting addressed by Price and David Williams (Alaw Goch).[56]

Much energy was expended during this period on conflicts between Anglicans and nonconformists over education. The establishment of the Aberdare School Board in 1871 brought about an extension of educational provision but also intensified religious rivalries. School Board elections were invariably fought on religious grounds. Despite these tensions the Board took over a number of existing schools and established new ones. By 1889, fourteen schools were operated by the Board but truancy and lack of attendance remained a problem, as in many industrial districts.[57]

In common with other public bodies at the time (see 'Local Government' above), membership of the School Board was dominated by coal owners and colliery officials, nonconformist ministers, professional men and tradesmen. Only occasionally was an Anglican clergyman elected and, with the exception of David Morgan (Dai o'r Nant), no working class candidates were elected for more than one term.[58]

Colleges

Secondary schools

- Aberdare Community School

- St. John the Baptist School (Aberdare)

- Ysgol Gyfun Rhydywaun

Transport

The town is served by Aberdare railway station and Aberdare bus station, opposite each other in the town centre. The town has also been subject to an extensive redevelopment scheme during 2012–13.

Sports

Aberdare Athletic F.C. were members of the Football League between 1921 and 1927 before being replaced by Torquay United after finishing bottom. The senior club folded a year later.[59] They played their football league games at the Aberdare Athletic Ground and were known as the Darians. The reserve team carried on as Aberaman and Aberdare Athletic for one more season and were known as Aberaman Athletic F.C. Now renamed as Aberdare Town They play in the Welsh League Division Two at Aberaman Park

Aberdare Rugby Football Club are a rugby union team formed in 1890 which still play in Aberdare today at the Ynys Stadium.

The Aberdare Athletic Ground was the venue of the first rugby league international, played between Wales and the New Zealand All Golds on New Year's Day 1908, which was won by the Welsh 9–8.[60]

Notable people

- See also Category:People from Aberdare

Notable current and former residents and natives of Aberdare include:

- Henry Austin Bruce – 1st Baron Aberdare & Home Secretary (1868–1873)

- Les Cartwright - Former Association Footballer and Wales international, played for Coventry City and Wrexham AFC

- Rose Davies – Labour politician and feminist

- Ian Evans – Former Rugby Union Player and Wales international, played for Ospreys and Bristol. Currently coaching at the Dragons

- Lyn Evans – particle physicist and project leader of the Large Hadron Collider

- Ioan Gruffudd – actor, born in Llwydcoed, Aberdare

- Patrick Hannan (presenter) – broadcaster

- Bethan Jenkins – member of the National Assembly for Wales for the South Wales (West) Region

- David "Tarw" Jones – Dual code rugby international

- Alun Lewis – War poet

- Lee Lucas - Association Footballer, played for Swansea City and Motherwell. Currently at Merthyr Town

- 'Big' Jim Mills (rugby league) – Wales & Great Britain rugby league international

- John Morgan – Canadian comedian, Royal Canadian Air Farce

- Mihangel Morgan – Welsh language writer, born in Trecynon, some of his literary works feature Aberdare

- Roy Noble – Welsh broadcaster, has lived near Aberdare for the past 30 years

- R. Ifor Parry – Congregationalist Minister and schoolteacher

- Jason Price - Former Association Footballer, played for Swansea City and Doncaster Rovers

- Thomas Price (Baptist minister) – Baptist Minister and radical politician

- Ieuan Rhys – actor, from Trecynon

- Rhys Hopkin Rhys – 19th century industrialist and prominent local figure

- Rhian Samuel – composer and professor of music

- Stereophonics – all three original members, Kelly Jones, Richard Jones and Stuart Cable were brought up in Cwmaman, Aberdare

- Rees Thomas - Former Association Footballer, played for Cardiff City, Bournemouth and Portsmouth

- Jo Walton – fantasy novelist, now living in Montreal, Quebec

- David Young – rugby player and coach, raised in Penywaun

References

- "Population estimates for Parishes in England and Wales, mid-2002 to mid-2017". Office for National Statistics (ONS). Retrieved 8 July 2019.

- Jones, Daniel (2006). Roach, Peter; Hartman, James; Setter, Jane (eds.). English Pronouncing Dictionary (17th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 2.

- "Population estimates for Parishes in England and Wales, mid-2002 to mid-2017". Office for National Statistics (ONS). Retrieved 8 July 2019.

- "Chronology of the History of the Cynon Valley". Cynon Valley History Society. Retrieved 19 December 2019.

- "Aberdare Conservation Area. Appraisal and Management Plan" (PDF). Rhondda Cynon Taf County Borough Council. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 December 2015. Retrieved 20 November 2013., pp.9–11

-

- Hoiberg, Dale H., ed. (2010). "Aberdare". Encyclopædia Britannica. I: A-ak Bayes (15th ed.). Chicago, IL: Encyclopædia Britannica Inc. pp. 27. ISBN 978-1-59339-837-8.

- Jones 1964, pp. 149–52.

- Jones. Statistical Evidence. p. 44.

- "Settlements" (PDF). Office for National Statistics. clickonwales.org. p. 1. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 8 January 2012.

- UK Census (2011). "Local Area Report – Aberdare Built-up area (1119885767)". Nomis. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 4 April 2018.

- "The Rhondda Cynon Taf (Communities) Order 2016" (PDF). Legislation.gov.uk. Retrieved 1 April 2018.

- Turner 1984, p. 6.

- "1847 Report into the State of Education in Wales"., p.489

- Jones. Communities. p. 272.

- "Public Meeting at Aberdare". Cardiff and Merthyr Guardian. 26 February 1848. Retrieved 20 November 2013.

- "St Elvan's Church Aberdare". Retrieved 12 June 2016.

- Jones 1964, pp. 155–6.

- Jones. Statistical Evidence., p.229

- Jones. Statistical Evidence. p. 287.

- "Comisiynydd y Gymraeg – 2011 Census results by Community". www.comisiynyddygymraeg.cymru. Archived from the original on 14 September 2017. Retrieved 23 March 2018.

- Jones 1964, p. 150.

- Jones 1964, pp. 149–50.

- Jones 1964, pp. 150–1.

- Davies, John, A History of Wales, Penguin, 1994, ISBN 0-14-014581-8, p 400

- Davies, op cit, p 400

- Davies, op cit, p 384

- Jones 1964, pp. 166–8.

- Barclay 1978, p. 24.

- Morgan 1991, pp. 23–5.

- Jones 1964, pp. 156–60.

- Jones 1964, p. 152.

- Rammell 1853, pp. 28–9.

- "Aberdare Board of Health". Cardiff and Merthyr Guardian. 22 September 1854. Retrieved 22 November 2013.

- Parry. "Labour Leaders and Local Politics": 400, 402. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Rhondda Cyon Taff County Borough Council Election Results 1995-2012, The Election Centre. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- County Borough Council Elections 2017, Rhondda Cynon Taf County Borough Council. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- Newman (1995), p.133

- Jones. Communities. pp. 88–104.

- "Glamorgan (Glamorgan, Mid), Aberdare, St. Elvan, Church Street, Victoria Square". The British Institute of Organ Studies2005. National Pipe Organ Register. 2005. Retrieved 11 April 2012.

- Newman (1995), p. 134

- Jones. Statistical Evidence. p. 447.

- Morgan. Rebirth of a Nation. pp. 134–5.

- "Editorial". Aberdare Leader. 19 November 1904. p. 4. Retrieved 11 February 2016.

- "Old v New Theology. Conflict at Abercwmboi". Aberdare Leader. 7 November 1908. Retrieved 14 March 2015.

- "Old Aberdare. History of Congregationalism". Aberdare Leader. 25 October 1913. Retrieved 19 January 2014.

- Rees, Chapels in the Valley, p.169

- "Saron Independent Chapel, Aberaman". britishlistedbuildings.co.uk. Retrieved 15 July 2012.

- Jones, Explorations and Explanations, p.197−8

- Alexander, D.T. (5 April 1913). "Old Aberdare. Leading Men and Establishments 50 Years Ago". Aberdare Leader. Retrieved 19 January 2014.

- Jones. Communities. pp. 269–70.

- Jones. Communities. p. 270.

- "Aberdare Unitarian Church". Ukunitarians.org.uk. Retrieved 28 May 2013.

- https://www.walesonline.co.uk/news/local-news/once-thriving-aberdare-jewish-community-recognised-8549278

- Jones. Communities. p. 274.

- "Aberdare British Schools". Cardiff and Merthyr Guardian. 14 October 1848. Retrieved 22 November 2013.

- Parry. "Labour Leaders and Local Politics": 401–2. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Parry. "Labour Leaders and Local Politics": 401–5. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Aberdare Athletic". Football Club History Database. Retrieved 15 July 2012.

- "The All Golds". Archived from the original on 10 October 2017. Retrieved 30 September 2018.

Sources

Books

- Jones, Dot (1998). Statistical Evidence relating to the Welsh Language 1801–1911. Cardiff: University of Wales Press. p. 44. ISBN 0708314600.

- Jones, Ieuan Gwynedd (1981). Explorations & Explanations. Essays in the Social History of Victorian Wales. Llandysul: Gomer. ISBN 0 85088 644 9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jones, Ieuan Gwynedd (1987). Communities. Essays in the Social History of Victorian Wales. Llandysul: Gomer. ISBN 0 86383 223 7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Morgan, Kenneth O (1991). Wales in British Politics 1868–1922 (3rd ed.). Cardiff: University of Wales Press. ISBN 0708311245.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Morgan, Kenneth O. (1981). Rebirth of a Nation. Wales 1889–1980. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-821760-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Newman, John (1995). Glamorgan. London: Penguin Group. ISBN 0140710566.

- Rees, D. Ben (1975). Chapels in the Valley. The Ffynnon Press. ISBN 0-902158-08-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Journals

- Barclay, Martin (1978). ""The Slaves of the Lamp". The Aberdare Miners Strike 1910" (PDF). Llafur: the journal of the Society for the Study of Welsh Labour History. 2 (3): 24–42. Retrieved 17 June 2020.

- Jones, Ieuan Gwynedd (1964). "Dr. Thomas Price and the election of 1868 in Merthyr Tydfil : a study in nonconformist politics (Part One)" (PDF). Welsh History Review. 2 (2): 147–172. Retrieved 15 October 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jones, Ieuan Gwynedd (1965). "Dr Thomas Price and the election of 1868 in Merthyr Tydfil: a study in nonconformist politics (Part Two)" (PDF). Welsh History Review. 2 (3): 251–70. Retrieved 15 October 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Parry, Jon (1989). "Labour Leaders and Local Politics 1888–1902: The Example of Aberdare" (PDF). Welsh History Review. 14 (3): 399–416. Retrieved 24 October 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Turner, Christopher B. (1984). "Religious revivalism and Welsh Industrial Society: Aberdare in 1859" (PDF). Llafur: the journal of the Society for the Study of Welsh Labour History. 4 (1): 4–13. Retrieved 9 September 2016.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wills, Wilton D. (1969). "The Rev. John Griffith and the revival of the established church in nineteenth century Glamorgan" (PDF). Morgannwg. 13: 75–102. Retrieved 6 November 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Newspapers

- Aberdare Leader

- Cardiff and Merthyr Guardian

Online

- Rammell, Thomas Webster (1853). "Report to the General Board of Health on a preliminary inquiry into the sewerage, drainage, and supply of water, and the sanitary condition of the inhabitants of the inhabitants of the parish of Aberdare in the county of Glamorgan". Internet Archive. General Board of Health. Retrieved 13 March 2017.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External sources

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Aberdare. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Aberdare. |