Slate industry in Wales

The existence of a slate industry in Wales is attested since the Roman period, when slate was used to roof the fort at Segontium, now Caernarfon. The slate industry grew slowly until the early 18th century, then expanded rapidly until the late 19th century, at which time the most important slate producing areas were in northwest Wales, including the Penrhyn Quarry near Bethesda, the Dinorwic Quarry near Llanberis, the Nantlle Valley quarries, and Blaenau Ffestiniog, where the slate was mined rather than quarried. Penrhyn and Dinorwig were the two largest slate quarries in the world, and the Oakeley mine at Blaenau Ffestiniog was the largest slate mine in the world.[1] Slate is mainly used for roofing, but is also produced as thicker slab for a variety of uses including flooring, worktops and headstones.[2]

Up to the end of the 18th century, slate was extracted on a small scale by groups of quarrymen who paid a royalty to the landlord, carted slate to the ports, and then shipped it to England, Ireland and sometimes France. Towards the close of the century, the landowners began to operate the quarries themselves, on a larger scale. After the government abolished slate duty in 1831, rapid expansion was propelled by the building of narrow gauge railways to transport the slates to the ports.

The slate industry dominated the economy of north-west Wales during the second half of the 19th century, but was on a much smaller scale elsewhere. In 1898, a work force of 17,000 men produced half a million tons of slate. A bitter industrial dispute at the Penrhyn Quarry between 1900 and 1903 marked the beginning of its decline, and the First World War saw a great reduction in the number of men employed in the industry. The Great Depression and Second World War led to the closure of many smaller quarries, and competition from other roofing materials, particularly tiles, resulted in the closure of most of the larger quarries in the 1960s and 1970s. Slate production continues on a much reduced scale.

The slate industry in North Wales is on the tentative World Heritage Site list[3] whilst Welsh slate has been designated by the International Union of Geological Sciences as a Global Heritage Stone Resource.[4]

Beginnings

The slate deposits of Wales belong to three geological series: Cambrian, Ordovician and Silurian. The Cambrian deposits run south-west from Conwy to near Criccieth; these deposits were quarried in the Penrhyn and Dinorwig quarries and in the Nantlle Valley. There are smaller outcrops elsewhere, for example on Anglesey. The Ordovician deposits run south-west from Betws-y-Coed to Porthmadog; these were the deposits mined at Blaenau Ffestiniog. There is another band of Ordovician slate further south, running from Llangynnog to Aberdyfi, quarried mainly in the Corris area, with a few outcrops in south-west Wales, notably Pembrokeshire. The Silurian deposits are mainly further east in the Dee valley and around Machynlleth.[5]

The virtues of slate as a building and roofing material have been recognized since the Roman period. The Roman fort at Segontium, Caernarfon, was originally roofed with tiles, but the later levels contain numerous slates, used for both roofing and flooring. The nearest deposits are about five miles (8 km) away in the Cilgwyn area, indicating that the slates were not used merely because they were available on-site.[6] During the mediaeval period, there was small-scale quarrying of slate in several areas. The Cilgwyn quarry in the Nantlle Valley dates from the 12th century, and is thought to be the oldest in Wales.[7] The first record of slate quarrying in the neighbourhood of the later Penrhyn Quarry was in 1413, when a rent-roll of Gwilym ap Griffith records that several of his tenants were paid 10 pence each for working 5,000 slates.[8] Aberllefenni Slate Quarry may have started operating as a slate mine as early as the 14th century. The earliest confirmed date of operating dates from the early 16th century when the local house Plas Aberllefenni was roofed in slates from this quarry.[9]

Transport problems meant that the slate was usually used fairly close to the quarries. There was some transport by sea. A poem by the 15th century poet Guto'r Glyn asks the Dean of Bangor to send him a shipload of slates from Aberogwen, near Bangor, to Rhuddlan to roof a house at Henllan, near Denbigh.[10] The wreck of a wooden ship carrying finished slates was discovered in the Menai Strait and is thought to date from the 16th century. By the second half of the 16th century, there was a small export trade of slates to Ireland from ports such as Beaumaris and Caernarfon.[11] Slate exports from the Penrhyn estate are recorded from 1713 when 14 shipments totalling 415,000 slates were sent to Dublin.[12] The slates were carried to the ports by pack-horses, and later by carts. This was sometimes done by women, the only female involvement in what was otherwise an exclusively male industry.[13]

Until the late 18th century, slate was extracted from many small pits by small partnerships of local men, who did not own the capital to expand further. The quarrymen usually had to pay a rent or royalty to the landlord, though the quarrymen at Cilgwyn did not. A letter from the agent of the Penrhyn estate, John Paynter, in 1738 complains that competition from Cilgwyn was affecting the sales of Penrhyn slates. The Cilgwyn slates could be extracted more cheaply and sold at a higher price.[14] Penrhyn introduced larger sizes of slate between 1730 and 1740, and gave these sizes the names which became standard. These ranged from "Duchesses", the largest at 24 inches (610 mm) by 12 inches (300 mm), through "Countesses", "Ladies" and "Doubles" to the smallest "Singles".[15]

Growth (1760–1830)

Methusalem Jones, previously a quarryman at Cilgwyn, began to work the Diffwys quarry at Blaenau Ffestiniog in the 1760s, which became the first large quarry in the area.[17] The large landowners were initially content to issue "take notes", allowing individuals to quarry slates on their lands for a yearly rent of a few shillings and a royalty on the slates produced.[18] The first landowner to take over the working of slates on his land was the owner of the Penrhyn estate, Richard Pennant, later Baron Penrhyn. In 1782, the men working quarries on the estate were bought out or ejected, and Pennant appointed James Greenfield as agent. The same year, Lord Penrhyn opened a new quarry at Caebraichycafn near Bethesda, which as Penrhyn Quarry would become the largest slate quarry in the world.[19] By 1792, this quarry was employing 500 men and producing 15,000 tons of slate per year.[20] At Dinorwig, a single large partnership took over in 1787, and in 1809 the landowner, Thomas Assheton Smith of Vaynol, took the management of the quarry into his own hands. The Cilgwyn quarries were taken over by a company in 1800, and the scattered workings at all three locations were amalgamated into a single quarry.[21] The first steam engine to be used in the slate industry was a pump installed at the Hafodlas quarry in the Nantlle Valley in 1807, but most quarries relied on hydropower to drive machinery.[22]

Wales was by now producing more than half the United Kingdom's output of slate, 26,000 tons out of a total UK production of 45,000 tons in 1793.[23] In July 1794, the government imposed a 20% tax on all slate carried coastwise, which put the Welsh producers at a disadvantage compared to inland producers who could use the canal network to distribute their product.[24] There was no tax on slates sent overseas, and exports to the United States gradually increased.[25] The Penrhyn Quarry continued to grow, and in 1799 Greenfield introduced the system of "galleries", huge terraces from 9 metres to 21 metres in depth.[26] In 1798, Lord Penrhyn constructed the horse-drawn Llandegai Tramway to transport slates from Penrhyn Quarry, and in 1801 this was replaced by the narrow gauge Penrhyn Quarry Railway, one of the earliest railway lines. The slates were transported to the sea at Port Penrhyn which had been constructed in the 1790s.[27] The Padarn Railway was opened in 1824 as a tramway for the Dinorwig Quarry, and converted to a railway in 1843. It ran from Gilfach Ddu near Llanberis to Port Dinorwic at Y Felinheli. The Nantlle Railway was built in 1828 and was operated using horse-power to carry slate from several slate quarries in the Nantlle Valley to the harbour at Caernarfon.[28]

Peak production (1831–1878)

Expansion at Blaenau Ffestiniog

In 1831 slate duty was abolished, and this helped to produce a rapid expansion in the industry, particularly since the duty on tiles was not abolished until 1833.[29] The Ffestiniog Railway line was constructed between 1833 and 1836 to transport slate from Blaenau Ffestiniog to the coastal town of Porthmadog, where it was loaded onto ships. The railway was graded so that loaded slate waggons could be run by gravity downhill all the way from Blaenau Ffestiniog to the port. The empty waggons were hauled back up by horses, which travelled down in 'dandy' waggons. This helped expansion at the Blaenau Ffestiniog quarries,[30] which had previously had to cart the slate to Maentwrog to be loaded onto small boats and taken down the River Dwyryd to the estuary, where it was transferred to larger vessels.[31] There was further expansion at Blaenau when John Whitehead Greaves, who had been running the Votty quarry since 1833, took a lease on the land between this quarry and the main Ffestiniog to Betws-y-Coed road. After years of digging he struck the famous Old Vein in 1846 in what became the Llechwedd quarry.[32] A fire which destroyed a large part of Hamburg in 1842 led to a demand for slate for rebuilding, and Germany became an important market, particularly for Ffestiniog slate.[33]

Mechanization and increased production

In 1843, the Padarn Railway became the first quarry railway to use steam locomotives, and the transport of slate by train rather than by ship was made easier when the London and North Western Railway built branches to connect Port Penrhyn and Port Dinorwic to the main line in 1852.[28] The Corris Railway opened as the horse-worked Corris, Machynlleth & River Dovey Tramroad in 1859, connecting the slate quarries around Corris and Aberllefenni with wharves on the estuary of the River Dyfi.[34] The Ffestiniog Railway converted to steam in 1863, and the Talyllyn Railway was opened in 1866 to serve the Bryn Eglwys quarry above the village of Abergynolwyn. Bryn Eglwys grew to be one of the largest quarries in mid Wales, employing 300 men and producing 30% of the total output of the Corris district.[35] The Cardigan Railway was opened in 1873, partly to carry slate traffic, and enabled the Glogue quarry in Pembrokeshire to grow to employ 80 men.[36]

Mechanization was gradually introduced to make most aspects of the industry more efficient, particularly at Blaenau Ffestiniog where the Ordovician slate was less brittle than the Cambrian slate further north, and therefore easier to work by machine. The slate mill evolved between 1840 and 1860, powered by a single line shaft running along the building and bringing together operations such as sawing, planing and dressing.[37] In 1859, John Whitehead Greaves invented the Greaves sawing table to produce blocks for the splitter, then in 1856 introduced a rotary machine to dress the split slate.[38] The splitting of the blocks to produce roofing slates proved resistant to mechanization, and continued to be done with a mallet and chisel. An extra source of income from the 1860s was the production of "slab", thicker pieces of slate which were planed and used for many purposes, for example flooring, tombstones and billiard tables.[2]

The larger quarries could be highly profitable. The Mining Journal estimated in 1859 that the Penrhyn quarries produced an annual net profit of GB£100,000, and the Dinorwig Quarry £70,000 a year.[39] From 1860 onwards slate prices rose steadily. Quarries expanded and the population of the quarrying districts increased, for example the population of Ffestiniog parish increased from 732 in 1801 to 11,274 in 1881.[40] Total Welsh production reached 350,000 tons a year by the end of the 1860s. Of this total, over 100,000 tons came from the Bethesda area, mainly from the Penrhyn Quarry. Blaenau Ffestiniog produced almost as much, and the Dinorwig Quarry alone produced 80,000 tons per year. The Nantlle Valley quarries produced 40,000 tons, while the remainder of Wales outside these areas produced only about 20,000 tons per year.[41] By the late 1870s, Wales was producing 450,000 tons of slate per year, compared with just over 50,000 tons for the rest of the United Kingdom, which then included Ireland.[42] In 1882, 92% of the United Kingdom's production was from Wales with the quarries at Penrhyn and Dinorwig producing half of this between them. Alun Richards comments on the importance of the slate industry:

It dominated the economy of the north-west of Wales, where, by the middle of the 19thC. it accounted for almost half the total revenues from trade, industry and the professions, and in Wales as a whole, its output value compared with that of coal.[43]

The prosperity of the slate industry led to the growth of a number of other associated industries. Shipbuilding increased at a number of coastal locations, particularly at Porthmadog, where 201 ships were built between 1836 and 1880.[44] Engineering companies were set up to supply the quarries, notably De Winton at Caernarfon. In 1870, De Winton built and equipped an entire workshop for the Dinorwig Quarry, with machinery powered by overhead shafting that in its turn was driven by the largest water-wheel in the United Kingdom, over 50 feet in diameter.[45]

Workers

There were several different categories of worker in the quarries. The quarrymen proper, who made up just over 50% of the workforce, worked the slate in partnerships of three, four, six or eight, known as "bargain gangs".[46] A gang of four typically consisted of two "rockmen" who would blast the rock to produce blocks, a splitter, who would split the blocks with hammer and chisel, and a dresser. A rybelwr would usually be a boy learning his trade, who would wander around the galleries offering assistance to the gangs. Sometimes a gang would give him a block of slate to split. Other groups were the "bad rockmen" who usually worked in crews of three, removing unworkable rock from the face, and the "rubbish men" who cleared the waste rock from the galleries and built the tips of waste which surrounded the quarry.[47] One ton of saleable slate could produce up to 30 tons of waste.

The bad rockmen and rubbish men were usually paid by the ton of material removed, but the quarrymen were paid according to a more complicated system. Part of the payment was determined by the number of slates the gang produced, but this could vary greatly according to the nature of the rock in the section allocated to them. The men would therefore be paid an extra sum of "poundage" per pound's worth of slate produced. "Bargains" were let by the setting steward, who would agree a price for a certain area of rock. If the rock in the bargain allocated to a gang was poor, they would be paid a higher poundage, while good rock meant a lower poundage.[48] The first Monday of every month was "bargain letting day" when these agreements were made between men and management. The men had to pay for their ropes and chains, for tools and for services such as sharpening and repairing. Subs (advances) were paid every week, everything being settled up on the "day of the big pay". If conditions had not been good, the men could end up owing the management money. This system was not finally abolished until after the Second World War.[49]

Because of this arrangement, the men tended to see themselves as independent contractors rather than employees on a wage, and trade unions were slow to develop. There were grievances however, including unfairness in setting bargains and disputes over days off. The North Wales Quarrymen's Union (NWQMU) was formed in 1874, and the same year there were disputes at Dinorwig and then at Penrhyn. Both these disputes ended in victory for the workers, and by May 1878, the union had 8,368 members.[50] One of the founders of the union, Morgan Richards, described in 1876 the conditions when he started work in the quarries forty years before:

I well remember the time when I was myself a child of bondage; when my father and neighbours, as well as myself, had to rise early, to walk five miles (8 km) before six in the morning, and the same distance home after six in the evening; to work hard from six to six; to dine on cold coffee, or a cup of buttermilk, and a slice of bread and butter; and to support (as some of them had to do) a family of perhaps five, eight or ten children on wages averaging from 12s to 16s a week.[51]

Industrial unrest and decline (1879–1938)

Labour disputes

In 1879, a period of twenty years of almost uninterrupted growth came to an end, and the slate industry was hit by a recession which lasted until the 1890s.[52] Management responded by tightening rules and making it more difficult for the men to take time off. Labour relations were worsened by differences in language, religion and politics between the two sides. The owners and top managers at most of the quarries were English-speaking, Anglican and Tory, while the quarrymen were Welsh-speaking and mainly Nonconformist and Liberal. Negotiations between the two sides usually involved the use of interpreters.[53] In October 1885, there was a dispute at Dinorwig over the curtailing of holidays which led to a lock-out lasting until February 1886.[54] At the Penrhyn Quarry, George Sholto Gordon Douglas-Pennant took over from his father Edward Gordon Douglas-Pennant in 1885, and in 1886 appointed E. A. Young as chief manager.[55] A more stringent management regime was introduced, and relations with the workforce deteriorated. This culminated in the suspension of 57 members of the union committee and 17 other men in September 1896, leading to a strike which lasted eleven months. The men were eventually obliged to go back to work, essentially on the management's terms, in August 1897. This strike became known as "The Penrhyn Lockout".[56]

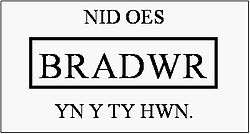

There was an upturn in trade in 1892, heralding another period of growth in the industry. This growth was mainly at Blaenau Ffestiniog and in the Nantlle Valley, where the workforce at Penyrorsedd reached 450.[57] Slate production in Wales peaked at over half a million tons in 1898, with 17,000 men employed in the industry.[58] A second lock-out or strike[59] at the Penrhyn Quarry began on 22 November 1900 and lasted for three years. The causes of the dispute were complex, but included the extension of a system of contracting out parts of the quarry. The quarrymen, instead of arranging their own bargains, would find themselves working for a contractor.[60] The union's funds for strike pay were inadequate, and there was a great deal of hardship among the 2,800 workers. Lord Penrhyn reopened the quarry in June 1901, and about 500 men returned to work, to be castigated as "traitors" by the remainder. Eventually the workers were forced to return to work in November 1903 on terms laid down by Lord Penrhyn. Many of the men considered to have been prominent in the union were not re-employed, and many of those who had left the area to seek work elsewhere did not return. The dispute left a lasting legacy of bitterness in the Bethesda area.[61]

Decline in production

The loss of production at Penrhyn led to a temporary shortage of slates and kept prices high, but part of the shortfall was made up by imports. French exports of slate to the UK increased from 40,000 tons in 1898 to 105,000 tons in 1902.[62] After 1903 there was a depression in the slate industry which led to reductions in pay and job losses. New techniques in tile manufacture had reduced costs, making tiles more competitive.[63] In addition, several countries had placed tariffs on the import of British slate, while a slump in the home building trade had reduced domestic demand; finally French slate producers had increased their exports to the United Kingdom. All of this led to a prolonged decline in demand for Welsh slate.[64] Eight Ffestiniog quarries closed between 1908 and 1913, and the Oakley dismissed 350 men in 1909.[62] R. Merfyn Jones comments:

The effects of this depression on the quarrying districts were deep and painful. Unemployment and emigration became constant features of the slate communities; distress was widespread. In the quarries there was short-time working, closures and reductions in earnings. Between 1906 and 1913 the number of men at work in the quarries of the Ffestiniog district shrank by 28 per cent, in Dyffryn Nantlle the number at work fell even more dramatically by 38 per cent.[65]

The First World War hit the slate industry badly, particularly in Blaenau Ffestiniog where exports to Germany had been an important source of income. Cilgwyn, the oldest quarry in Wales, closed in 1914, though it later reopened. In 1917, slate quarrying was declared a non-essential industry and a number of quarries were closed for the remainder of the war.[66] The demand for new houses after the end of the war brought back a measure of prosperity; in the slate mines of Blaenau Ffestiniog production was almost back to 1913 levels by 1927, but in the quarries the output was still well below the pre-war level.[67] The Great Depression in the 1930s led to cuts in production, with exports particularly hard hit.[68]

The quarries and mines made increasing use of mechanization from the start of the 20th century, with electricity replacing steam and water as a power source. The Llechwedd quarry introduced its first electrical plant in 1891, and in 1906, a hydro-electric plant was opened in Cwm Dyli, on the lower slopes of Snowdon, which supplied electricity to the largest quarries in the area.[69] The use of electric saws and other machinery reduced the hard manual labour involved in extracting the slate, but produced much more slate dust than the old manual methods, leading to an increased incidence of silicosis.[70] The work was also dangerous in other ways, with the blasting operations responsible for many deaths. A government enquiry in 1893 found that the death rate for underground workers in the slate mines was 3.23 per thousand, higher than the rate for coal miners.[49]

End of large-scale production (1939–2005)

%2C_Blaenau_Ffestiniog_(14117319357).jpg)

The outbreak of World War II in 1939 led to a severe drop in trade. Part of the Manod quarry at Blaenau Ffestiniog was used to store art treasures from the National Gallery and the Tate Gallery. The number of men employed in the slate industry in North Wales dropped from 7,589 in 1939 to 3,520 by the end of the war.[71] In 1945, total production was only 70,000 tons a year, and fewer than 20 quarries were still open compared with 40 before the war.[72] The Nantlle Valley had been particularly hard hit, with only 350 workers employed in the entire district, compared with 1,000 in 1937.[73] Demand for slate was dropping as tiles were increasingly used for roofing, and imports from countries such as Portugal, France and Italy were increasing. There was some increased demand for slates to repair bombed buildings after the end of the war, but the use of slate for new buildings was banned, apart from the smallest sizes. This ban was lifted in 1949.[74]

Total production of slate in Wales declined from 54,000 tons in 1958 to 22,000 tons in 1970.[75] The Diffwys quarry at Blaenau Ffestiniog closed in 1955 after almost two centuries of operation.[76] The nearby Votty and Bowydd quarries closed in 1963. In 1969, Dinorwic quarry closed, and over 300 quarrymen lost their jobs. The following year the Dorothea quarry in the Nantlle Valley and the Braichgoch quarry near Corris announced their closure. Oakeley at Blaenau Ffestiniog closed in 1971, but was later reopened by another company.[77] By 1972,fewer than 1,000 men were employed in the North Wales slate industry.[71] There was little alternative employment in the slate-producing areas, and the closures resulted in high unemployment and a drop in population as younger people moved away to find work.

For many years, the quarry owners had denied that slate dust was the cause of the high levels of silicosis suffered by quarrymen. From 1909, they had been responsible for all accidents and illnesses caused by the work, but had managed to persuade successive governments that slate dust was harmless.[64] In 1979, after a long struggle, the government recognized silicosis as an industrial disease meriting compensation.[70] There was an increase in demand for slate in the 1980s, and although this came too late for many quarries there was still some production in the Blaenau Ffestiniog area at the Oakeley, Llechwedd and Cwt-y-Bugail quarries, though the bulk of roofing slate production was at the Penrhyn Quarry. Further mechanization was introduced, with a computerized laser beam being used to aid the sawing of the slate blocks.[69]

Welsh slate today

Quarries still producing slate

The Penrhyn Quarry is still producing slate, though at a much reduced capacity from its heyday at the end of the 19th century. In 1995, it accounted for almost 50% of UK production.[78] It is currently owned and operated by Welsh Slate Ltd (part of the Breedon Group [79]). It was previously owned by the Lagan Group, which also owned and carried out some operations at the Oakeley quarry at Blaenau Ffestiniog, the Pen yr Orsedd quarry in the Nantlle Vale, and the Cwt-y-Bugail quarry.[80] In March 2010 the company announced its decision to mothball the Oakeley quarry because of subsidence at the site.[81]

The Greaves Welsh Slate Company produces roofing slates and other slate products from Llechwedd, and work also continues at the Berwyn Quarry near Llangollen. The final large-scale underground working to close was Maenofferen, associated with the Llechwedd tourist mine, in 1999: part of this site, now effectively amalgamated with Votty / Bowydd, is still worked by untopping.[82] The Wales Millennium Centre in Cardiff uses waste slate in many different colours in its design: purple slate from Penrhyn, blue from Cwt-y-Bugail, green from Nantlle, grey from Llechwedd, and black from Corris.[83]

Visitor attractions

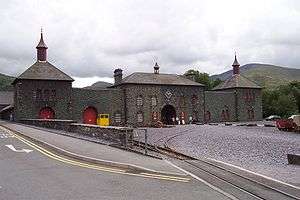

Part of the Dinorwig Slate Quarry is now within the Padarn Country Park, and the other part houses the Dinorwig power station in caverns under the old quarry workings. The National Slate Museum is located in some of the quarry workshops. The museum has displays including Victorian slate-workers' cottages that once stood at Tanygrisiau near Blaenau Ffestiniog. As well as many exhibits, it has the multi-media display To Steal a Mountain, showing the lives and work of the men who quarried slate here. The museum has the largest working water wheel in the United Kingdom, which is available for viewing via several walkways, and a restored incline formerly used to carry slate waggons uphill and downhill.[84]

In Blaenau Ffestiniog, the Llechwedd Slate Caverns have been converted into a visitor attraction.[85] Visitors can travel on the Miners' Tramway or descend into the Deep Mine, via a funicular railway which uses an old incline, to explore this former slate mine and learn how slate was extracted and processed and about the lives of the miners. The Deep Mine, opened in 1979, is accessed by Britain's steepest passenger railway, with a gradient of 1:1.8 or 30°. In the chambers, formed by slate extraction, sound and light is used to tell the story of the mine and mining.[86] The Braichgoch slate mines at Corris have been converted into a tourist attraction named "King Arthur's Labyrinth" where visitors are taken underground by boat along a subterranean river. They then walk through the caverns to see audiovisual presentations of the Arthurian legends and stories from the Mabinogion and the tales of Taliesin.[87] The Llwyngwern quarry near Machynlleth is now the site of the Centre for Alternative Technology. A number of the railways which carried the slates to the ports have been restored as tourist attractions, for example the Ffestiniog Railway and the Talyllyn Railway.[88]

Cultural influences

The Welsh slate industry was essentially a Welsh-speaking industry. Most of the workforce in the main slate-producing areas of North Wales were drawn from the local area, with little immigration from outside Wales. The industry had a considerable influence on the culture of the area and on that of Wales as a whole. The caban, the cabin where the quarrymen gathered for their lunch break, was often the scene of wide-ranging discussions, which were often formally minuted. A surviving set of minutes from a caban at the Llechwedd mine at Blaenau Ffestiniog for 1908–10 records discussions on Church Disestablishment, tariff reform and other political topics.[89] Eisteddfodau were held, poetry composed and discussed and most of the larger quarries had their own band, with the Oakley band particularly famous. Burn calculates that there are around fifty men judged worthy of an entry in the Dictionary of Welsh Biography who started their working lives as slate quarrymen, compared to only four owners, though obviously there was also a distinct disparity in the numbers of the two groups.[90]

A number of Welsh writers have drawn on the lives of the quarrymen for their material, for example the novels of T. Rowland Hughes. Chwalfa, translated into English as Out of their night (1954), has the Penrhyn Quarry dispute as a background, while Y cychwyn, translated as The beginning (1969), follows the apprenticeship of a young quarryman. Several novels by Kate Roberts, the daughter of a quarryman, give a picture of the area around Rhosgadfan, where the slate industry was on a smaller scale and many of the quarrymen were also smallholders. Her novel Traed mewn cyffion (1936), translated as Feet in chains (2002), gives a vivid picture of the struggles of a quarrying family in the period between 1880 and 1914. Y Chwarelwr ("The Quarryman") produced in 1935 was the first Welsh-language film. It showed various aspects of a slate quarryman's life at Blaenau Ffestiniog.[91]

Notes

- Jones p. 72

- Lindsay p. 133

- "Tentavive World Heritage Site List UK". Unesco.org. Retrieved 25 January 2016.

- "Designation of GHSR". IUGS Subcommission: Heritage Stones. Retrieved 24 February 2019.

- Richards 1995 pp. 10–11

- Lindsay p. 18. Slate flagstones were also used at the smaller fort of Caer Llugwy between Capel Curig and the Conwy Valley.

- Lindsay p. 314

- Lindsay p. 27

- Richards 1995 p. 13

- Lindsay p. 14

- Lindsay p. 24

- "Port Penrhyn website". Port Penrhyn Port Authority. Archived from the original on 18 February 2006. Retrieved 6 September 2006.

- For example the pack-horses carrying Penrhyn slate were usually tended by girls; see Richards 1999 p. 19

- Lindsay pp. 29–30

- Lindsay pp, 36–7

- Lindsay p. 30

- Lewis p. 6

- Richards 1995 pp. 16–17

- Lindsay p. 45

- Richards pp. 21–22

- Lewis p.5

- Williams p. 16

- Williams p. 5

- Lindsay pp. 91–2

- Lindsay p. 99

- Williams p. 10

- Lindsay pp. 49–50

- Richards 1999 p. 15

- Lindsey p. 117

- Strictly speaking, most of the slate produced in the Blaenau Ffestiniog area was mined from underground workings rather than quarried. These workings are frequently called "quarries" in the industry, and many began as surface workings.

- Hughes p. 23

- Burn p. 5

- Hughes p. 31

- Holmes p. 13

- Holmes pp. 9, 11

- Richards 1995 p. 95

- Williams pp. 15–16

- Williams pp. 16–19

- Jones pp. 121–1

- Richards 1995 p. 122

- Richards 1995 pp. 115–6

- Richards 1995 p. 123

- Richards 1995 p. 8

- Hughes p. 37

- "Welsh Slate Museum website: The Water Wheel". Welsh Slate Museum. Archived from the original on 13 January 2007. Retrieved 13 September 2006.

- Jones pp. 72–3

- Jones p. 73

- Jones pp. 81–2

- Williams p. 27

- Jones p. 112

- Quoted in Burn p. 10

- Jones p. 113

- Jones pp. 49–71

- Jones pp. 149–160

- Lindsay pp. 264–5

- Jones pp. 186-95

- Richards 1995 p. 145

- Richards 1995 p. 146

- The question of whether the dispute was a lock-out or a strike can still arouse strong feelings in the Bethesda area a century later. See Richards 1995 p. 146.

- Jones p. 211

- Jones pp. 210–66

- Burn p. 17

- Lindsay p. 256–7

- Engineering and Mining Journal

- Jones p. 295

- Lindsay p. 260

- Pritchard p. 24

- Lindsay p. 294

- Williams p. 19

- Williams p. 30

- Lindsay p. 298

- Richards 1995 p. 182

- Richards 1995 pp. 183, 220–1

- Richards pp. 183–4

- Lindsay p. 303

- Richards 1995 p. 185

- Lindsay pp. 305–6

- Richards 1995 p. 191

- "Quarry firm Welsh Slate sold as part of multi-million pound deal". Daily Post. 17 April 2018. Retrieved 8 November 2018.

- Trewyn, Hywel (18 March 2010). "Blaenau Ffestiniog jobs blow as quarry shuts". Caernarfon and Denbigh Herald. Trinity Mirror North West & North Wales. Retrieved 29 September 2010.

- "Quarry losses hit Snowdonia town". BBC. 17 March 2010. Retrieved 29 September 2010.

- "Untopping" involves recovering slate from former slate mines by digging from the surface to remove the pillars which formerly separated the chambers. These pillars usually contain good slate.

- "Wales Millennium Centre". SPG Media Limited. Archived from the original on 9 October 2007. Retrieved 29 September 2010.

- "Welsh Slate Museum website". Welsh Slate Museum. Retrieved 6 September 2006.

- Richards 1995 p. 188

- "Llechwedd Slate Caverns website". Llechwedd Slate Caverns. Retrieved 13 September 2006.

- "King Arthur's Labyrinth website". King Arthur's Labyrinth Ltd. Archived from the original on 8 October 2006. Retrieved 13 September 2006.

- Richards 1999 p. 14

- Burn p. 14

- Burn p. 15

- "National Screen and Sound Archive for Wales". National Library of Wales. Archived from the original on 2 October 2006. Retrieved 13 September 2006.

References

- Burn, Michael. 1972. The Age of Slate. Quarry Tours Ltd., Blaenau Ffestiniog.

- "Slate Mining in Wales and Cause of Its Decline". The Engineering and Mining Journal: 145–148. 18 January 1908. Retrieved 15 February 2020.

- Holmes, Alan. 1986. Slates from Abergynolwyn: the story of Bryneglwys Slate Quarry Gwynedd Archives Service. ISBN 0-901337-42-0

- Hughes, Emrys & Aled Eames. 1975. Porthmadog Ships. Gwynedd Archives Service.

- Jones, Gwynfor Pierce & Alun John Richards. 2004. Cwm Gwyrfai : the quarries of the North Wales narrow gauge and the Welsh Highland railways. Gwasg Carreg Gwalch. ISBN 0-86381-897-8

- Jones, R. Merfyn. 1981. The North Wales Quarrymen, 1874–1922 (Studies in Welsh history; 4.) University of Wales Press. ISBN 0-7083-0776-0

- Lewis, M.J.T. & Williams, M. C. 1987. Pioneers of Ffestiniog Slate. Snowdonia National Park Study Centre, Plas Tan y Bwlch. ISBN 0-9512373-1-4

- Lindsay, Jean. 1974. A History of the North Wales Slate Industry. David and Charles, Newton Abbot. ISBN 0-7153-6264-X

- Pritchard, D. Dylan. 1946. The Slate Industry of North Wales: statement of the case for a plan. Gwasg Gee.

- Richards, Alun John. 1994. Slate Quarrying at Corris. Gwasg Carreg Gwalch. ISBN 0-86381-279-1

- Richards, Alun John. 1995. Slate Quarrying in Wales Gwasg Carreg Gwalch. ISBN 0-86381-319-4

- Richards, Alun John. 1998. The Slate Quarries of Pembrokeshire Gwasg Carreg Gwalch. ISBN 0-86381-484-0

- Richards, Alun John. 1999. The Slate Regions of North and Mid Wales and Their Railways Gwasg Carreg Gwalch. ISBN 0-86381-552-9

- Williams, Merfyn. 1991. The Slate Industry. Shire Publications, Aylesbury. ISBN 0-7478-0124-X

External links

- The slate industry of North and Mid Wales, by Dave Sallery

- Slatesite: a website about Welsh slate

- Welsh Slate Museum website

- Aditnow - A mine exploration website

- Mine Explorer - A mine exploration website

- A website about the Oakeley Dynasty

- Economic history of the Welsh slate industry to 1945

- The Dinorwic Slate Quarry on Vimeo

- A Guide to Slate and its History in Wales