Northern England

Northern England, also known as the North of England or simply the North, is the northern part of England, considered as a single cultural area.

Northern England North of England, the North Country | |

|---|---|

| Nickname(s): The North | |

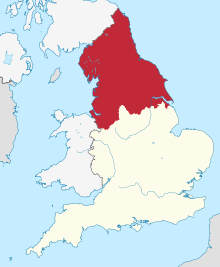

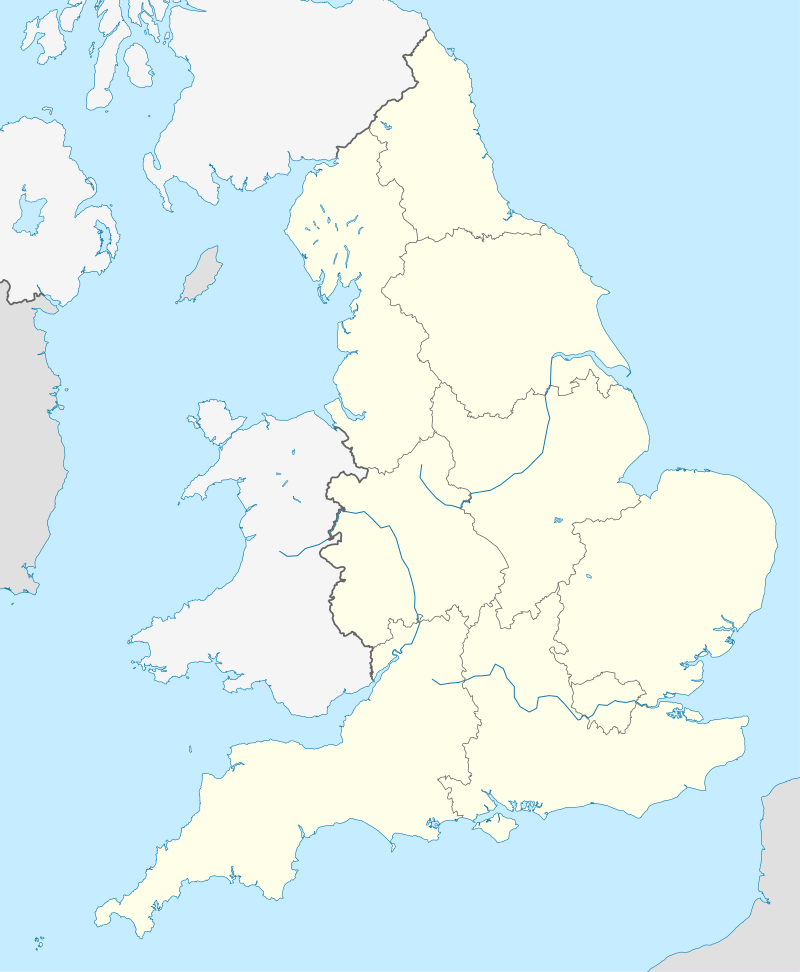

The three Northern England government regions shown within England, without regional boundaries. Other cultural definitions of the North vary. | |

| Sovereign state | |

| Constituent country | |

| Historic counties | |

| Largest settlements | |

| Area | |

| • Total | 37,331 km2 (14,414 sq mi) |

| Population (2011 census)[1] | |

| • Total | 14,933,000 |

| • Density | 400/km2 (1,000/sq mi) |

| • Urban | 12,782,940 |

| • Rural | 2,150,060 |

| Demonym(s) | Northerner |

| Time zone | GMT (UTC) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+1 (BST) |

Northern England is bordered by the Midlands to the south. It extends from the Anglo-Scottish border in the north to near the River Trent in the south, although precise definitions of its southern extent vary. Northern England approximately comprises three statistical regions: the North East, North West and Yorkshire and the Humber. These have a combined population of around 14.9 million as of the 2011 Census and an area of 37,331 km2 (14,414 sq mi). Northern England contains much of England's national parkland but also has large areas of urbanisation, including the conurbations of Greater Manchester, Merseyside, Teesside, Tyneside, Wearside, and South and West Yorkshire.

The region has been controlled by many groups, from the Brigantes, the largest Brythonic kingdom of Great Britain, to the Romans, to Anglo-Saxons and Danes. After the Norman conquest in 1066, the Harrying of the North brought destruction. The area experienced Anglo-Scottish border fighting until the personal union of England and Scotland under the Stuarts, with some parts changing hands between England and Scotland many times. Many of the innovations of the Industrial Revolution began in Northern England, and its cities were the crucibles of many of the political changes that accompanied this social upheaval, from trade unionism to Manchester Capitalism. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the economy of the North was dominated by heavy industry such as weaving, shipbuilding, steel-making and mining. The deindustrialisation that followed in the second half of the 20th century hit Northern England hard, and many towns remain deprived compared with those in Southern England.

Urban renewal projects and the transition to a service economy have resulted in strong economic growth in some parts of Northern England, but a definite North–South divide remains both in the economy and the culture of England. Centuries of migration, invasion and labour have shaped Northern culture, and the region retains distinctive dialects, music and cuisine.

Definitions

For government and statistical purposes, Northern England is defined as the area covered by the three statistical regions of North East England, North West England and Yorkshire and the Humber.[2] This area consists of the ceremonial counties of Cheshire, Cumbria, County Durham, East Riding of Yorkshire, Greater Manchester, Lancashire, Merseyside, Northumberland, North Yorkshire, South Yorkshire, Tees Valley, Tyne and Wear and West Yorkshire, plus the unitary authority areas of North Lincolnshire and North East Lincolnshire. This definition will be used in this article, except when otherwise stated.

Other definitions use historic county boundaries, in which case the North is generally taken to comprise Cumberland, Northumberland, Westmorland, County Durham, Lancashire and Yorkshire, often supplemented by Cheshire,[3] or are drawn without reference to human borders, using geographic features such as the River Mersey and River Trent.[4] The Isle of Man is occasionally included in definitions of "the North" (for example, by the Survey of English Dialects, VisitBritain and BBC North West), although it is politically and culturally distinct from England.[3]

Some areas of Derbyshire, Lincolnshire, Nottinghamshire and Staffordshire have Northern characteristics and include satellites of Northern cities.[4] Towns in the High Peak borough of Derbyshire are included in the Greater Manchester Built-Up Area, as villages and hamlets there such as Tintwistle, Crowden and Woodhead were formerly in Cheshire before local government boundary changes in 1974,[5] due to their close proximity to the city of Manchester, and before this the borough was considered to be part of the Greater Manchester Statutory City Region. More recently, the Chesterfield, North East Derbyshire, Bolsover, and Derbyshire Dales districts have joined with districts of South Yorkshire to form the Sheffield City Region, along with the Bassetlaw District of Nottinghamshire, although for all other purposes these districts still remain in their respective East Midlands counties. The geographer Danny Dorling includes most of the West Midlands and part of the East Midlands in his definition of the North, claiming that "ideas of a midlands region add more confusion than light".[6] Conversely, more restrictive definitions also exist, typically based on the extent of the historical Northumbria, which exclude Cheshire and Lincolnshire.[7] [lower-alpha 1]

Personal definitions of the North vary greatly and are sometimes passionately debated. When asked to draw a dividing line between North and South, Southerners tend to draw this line further south than Northerners do.[7] From the Southern perspective, Northern England is sometimes defined jokingly as the area north of the Watford Gap between Northampton and Leicester[lower-alpha 2] – a definition which would include much of the Midlands.[7][9] Various cities and towns have been described as or promoted themselves as the "gateway to the North", including Crewe,[10] Stoke-on-Trent,[11] and Sheffield.[12] For some in the northernmost reaches of England, the North starts somewhere in North Yorkshire around the River Tees – the Yorkshire poet Simon Armitage suggests Thirsk, Northallerton or Richmond – and does not include cities like Manchester and Leeds, nor the majority of Yorkshire.[13][14] Northern England is not a homogeneous unit,[15] and some have entirely rejected the idea that the North exists as a coherent entity, claiming that considerable cultural differences across the area overwhelm any similarities.[16][17]

Geography

Through the North of England run the Pennines, an upland chain sometimes referred to as "the backbone of England", which stretches from the Tyne Gap to the Peak District. Other uplands in the North include the Lake District with England's highest mountains, the Cheviot Hills adjoining the border with Scotland, and the North York Moors near the North Sea coastline.[18] The geography of the North has been heavily shaped by the ice sheets of the Pleistocene era, which often reached as far south as the Midlands. Glaciers carved deep, craggy valleys in the central uplands, and, when they melted, deposited large quantities of fluvio-glacial material in lowland areas like the Cheshire and Solway Plains.[19] On the eastern side of the Pennines, a former glacial lake forms the Humberhead Levels: a large area of fenland which drains into the Humber and which is very fertile and productive farmland.[19]

Much of the mountainous upland remains undeveloped, and of the ten national parks in England, five – the Peak District, the Lake District, the North York Moors, the Yorkshire Dales, and Northumberland National Park – are located partly or entirely in the North.[lower-alpha 3] [20][21] The Lake District includes England's highest peak, Scafell Pike, which rises to 978 m (3,209 ft), its largest lake, Windermere, and its deepest lake, Wastwater.[22] Northern England is one of the most treeless areas in Europe, and to combat this the government plans to plant over 50 million trees in a new Northern Forest across the region.[23]

.jpg)

Vast urban areas have emerged along the coasts and rivers, and they run almost contiguously into each other in places. The needs of trade and industry have produced an almost continuous thread of urbanisation from the Wirral Peninsula to Doncaster, taking in the cities of Liverpool, Manchester, Leeds, and Sheffield, with a population of at least 7.6 million.[24] Uniquely for such a large urban belt in Europe, these cities are all recent; most of them started as scattered villages with no shared identity before the Industrial Revolution.[25] On the east coast, trade fuelled the growth of major ports such as Kingston upon Hull and Newcastle upon Tyne,[lower-alpha 4] [25] and the riverside conurbations of Teesside, Tyneside and Wearside became the largest towns in the North East.[26] Northern England is now heavily urbanised: analysis by The Northern Way in 2006 found that 90% of the population of the North lived in one of its city regions: Liverpool, Central Lancashire, Manchester, Sheffield, Leeds, Hull and Humber Ports, Tees Valley and Tyne and Wear.[27] As of the 2011 census, 86% of the Northern population lived in urban areas as defined by the Office for National Statistics, compared to 82% for England as a whole.[28]

Natural resources

Peat is found in thick, plentiful layers across the Pennines and Scottish Borders, and there are many large coalfields, including the Great Northern, Lancashire and South Yorkshire Coalfields.[19] Millstone grit, a distinctive coarse-grained rock used to make millstones, is widespread in the Pennines,[19] and the variety of other rock types is reflected in the architecture of the region, such as the bright red sandstone seen in buildings in Chester, the cream-buff Yorkstone and the distinctive purple Doddington sandstone.[29] These sandstones also mean that apart from the east coast, most of Northern England has very soft water, and this has influenced not just industry, but even the blends of tea enjoyed in the region.[30][31]

Rich deposits of iron ore are found in Cumbria and the North East, and fluorspar and baryte are also plentiful in northern parts of the Pennines.[32] Salt mining in Cheshire has a long history, and both remaining rock salt mines in Great Britain are in the North: Winsford Mine in Cheshire and Boulby Mine in North Yorkshire, which also produces half of the UK's potash.[33][34]

Climate

.jpg)

Northern England has a cool, wet oceanic climate with small areas of subpolar oceanic climate in the uplands.[36] Averaged across the entire region,[lower-alpha 5] Northern England is cooler, wetter and cloudier than England as a whole, and contains both England's coldest point (Cross Fell) and its rainiest point (Seathwaite Fell). Its temperature range and sunshine duration is similar to the UK average and it sees substantially less rainfall than Scotland or Wales. These averages disguise considerable variation across the region, due chiefly to the upland regions and adjacent seas.[35][38]

The prevailing winds across the British Isles are westerlies bringing moisture from the Atlantic Ocean; this means that the west coast frequently receives strong winds and heavy rainfall while the east coast lies in a rain shadow behind the Pennines. As a result, Teesside and the Northumbrian coast are the driest regions in the North, with around 600 mm (24 in) of rain per year, while parts of the Lake District receive over 3,200 mm (130 in). Lowland regions in the more southern parts of Northern England such as Cheshire and South Yorkshire are the warmest, with average maximum July temperatures of over 21 °C (70 °F), while the highest points in the Pennines and Lake District reach only 17 °C (63 °F). The area has a reputation for cloud and fog – especially along its east coast, which experiences a distinctive sea fog known as fret – although the Clean Air Act 1956 and decline of heavy industry have seen sunshine duration increase in urban areas in recent years.[35]

| Climate data for the England N climate region, 1981–2010 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 6.4 (43.5) |

6.6 (43.9) |

8.8 (47.8) |

11.4 (52.5) |

14.7 (58.5) |

17.3 (63.1) |

19.4 (66.9) |

19.1 (66.4) |

16.5 (61.7) |

12.8 (55.0) |

9.1 (48.4) |

6.7 (44.1) |

12.4 (54.3) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 0.7 (33.3) |

0.6 (33.1) |

2.1 (35.8) |

3.4 (38.1) |

6.0 (42.8) |

8.9 (48.0) |

11.0 (51.8) |

10.9 (51.6) |

8.9 (48.0) |

6.2 (43.2) |

3.2 (37.8) |

0.9 (33.6) |

5.3 (41.5) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 94.1 (3.70) |

69.2 (2.72) |

75.2 (2.96) |

64.9 (2.56) |

61.0 (2.40) |

71.9 (2.83) |

72.3 (2.85) |

82.4 (3.24) |

80.8 (3.18) |

100.6 (3.96) |

98.1 (3.86) |

99.2 (3.91) |

969.8 (38.18) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1 mm) | 14.2 | 11.1 | 12.5 | 10.9 | 10.5 | 10.7 | 10.7 | 11.5 | 10.9 | 13.6 | 14.3 | 13.7 | 144.5 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 49.4 | 70.5 | 101.9 | 142.4 | 182.8 | 166.7 | 175.6 | 164.0 | 126.7 | 94.0 | 58.7 | 43.5 | 1,376.2 |

| Source: Met Office[38] | |||||||||||||

Language and dialect

English

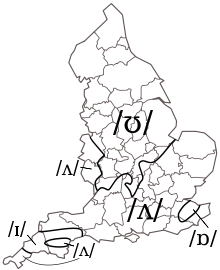

The English spoken today in the North has been shaped by the area's history, and some dialects retain features inherited from Old Norse and the local Celtic languages.[40] Dialects spoken in the North include Cumbrian (Cumbria), Geordie (Tyneside), Lancashire (Lancashire), Mancunian (Manchester), Northumbrian (Northumberland and Durham), Pitmatic (former mining communities of Northumberland/County Durham), Scouse (Liverpool) and Tyke (Yorkshire). Linguists have attempted to define a Northern dialect area, corresponding to the area north of a line that begins at the Humber estuary and runs up the River Wharfe and across to the River Lune in north Lancashire.[41] This area corresponds roughly to the sprachraum of the Old English Northumbrian dialect, although the linguistic elements that defined this area in the past, such as the use of doon instead of down and substitution of an ang sound in words that end -ong (lang instead of long), are now prevalent only in the more northern parts of the region. As speech has changed, there is little consensus on what defines a "Northern" accent or dialect.[42]

Northern English accents have not undergone the TRAP–BATH split, and a common shibboleth to distinguish them from Southern ones is the Northern use of the short a (the near-open front unrounded vowel) in words such as bath and castle.[43] On the opposite border, most Northern English accents can be distinguished from Scottish accents because they are non-rhotic, although a few rhotic Lancashire accents remain.[44] Other features common to many Northern English accents are the absence of the FOOT–STRUT split (so put and putt are homophones), the reduction of the definite article the to a glottal stop (usually represented in writing as t' or occasionally th', although it is often not pronounced as a /t/ sound) or its total elision, and the T-to-R rule that leads to the pronunciation of t as a rhotic consonant in phrases like get up ([ɡɛɹ ʊp]).[45]

The pronouns thou and thee survive in some Northern English dialects, although these are dying out outside very rural areas, and many dialects have an informal second-person plural pronoun: either ye (common in the North East) or yous (common in areas with historical Irish communities).[46] Many dialects use me as a possessive ("me car") and some treat us likewise ("us cars") or use the alternative wor ("wor cars"). Possessive pronouns are also used to mark the names of relatives in speech (for example, a relative called Joan would be referred to as "our Joan" in conversation).[47]

With urbanisation, distinctive urban accents have arisen which often differ greatly from the historical accents of the surrounding rural areas and sometimes share features with Southern English accents.[42] Northern English dialects remain an important part of the culture of the region, and the desire of speakers to assert their local identity has led to accents such as Scouse and Geordie becoming more distinctive and spreading into surrounding areas.[48]

Other languages

There are no recognised minority languages in Northern England, although the Northumbrian Language Society campaigns to have the Northumbrian dialect recognised as a separate language.[49] It is possible that traces of now-extinct Brythonic Celtic languages from the region survive in some rural areas in the Yan Tan Tethera counting systems traditionally used by shepherds.[50]

Contact between English and immigrant languages has given rise to new accents and dialects. For instance, the variety of English spoken by Poles in Manchester is distinct both from typical Polish-accented English and from Mancunian.[51] At a local level, the diversity of immigrant communities means that some languages that are extremely rare in the country as a whole have strongholds in Northern towns: Bradford for instance has the largest proportion of Pashto speakers, while Manchester has most Cantonese speakers.[52]

History

The prehistoric North

Apr2006.jpg)

During the ice ages, Northern England was buried under ice sheets, and little evidence remains of habitation – either because the climate made the area uninhabitable, or because glaciation destroyed most evidence of human activity.[54] The northern-most cave art in Europe is found at Creswell Crags in northern Derbyshire, near modern-day Sheffield, which shows signs of Neanderthal inhabitation 50 to 60 thousand years ago, and of a more modern occupation known as the Creswellian culture around 12,000 years ago.[55] Kirkwell Cave in Lower Allithwaite, Cumbria shows signs of the Federmesser culture of the Paleolithic, and was inhabited some time between 13,400 and 12,800 years ago.[56]

Significant settlement appears to have begun in the Mesolithic era, with Star Carr in North Yorkshire generally considered the most significant monument of this era.[57][58] The Star Carr site includes Britain's oldest known house, from around 9000 BC, and the earliest evidence of carpentry in the form of a carved tree trunk from 11000 BC.[57][59]

The Lincolnshire and Yorkshire Wolds around the Humber Estuary were settled and farmed in the Bronze Age, and the Ferriby Boats – one of the best-preserved finds of the era – were discovered near Hull in 1937.[60] In the more mountainous regions of the Peak District, hillforts were the main Bronze Age settlement and the locals were most likely pastoralists raising livestock.[61]

Iron Age and the Romans

Roman histories name the Celtic tribe that occupied the majority of Northern England as the Brigantes, likely meaning "Highlanders". Whether the Brigantes were a unified group or a looser federation of tribes around the Pennines is debated, but the name appears to have been adopted by the inhabitants of the region, which was known by the Romans as Brigantia.[62] Other tribes mentioned in ancient histories, which may have been part of the Brigantes or separate nations, are the Carvetii of modern-day Cumbria and the Parisi of east Yorkshire.[63]

The Brigantes allied with the Roman Empire during the Roman conquest of Britain: Tacitus records that they handed the resistance leader Caratacus over to the Empire in 51.[64] Power struggles within the Brigantes made the Romans wary, and they were conquered in a war beginning in the 70s under the governorship of Quintus Petillius Cerialis.[65] The Romans created the province of "Britannia Inferior" (Lower Britain) in the North, and it was ruled from the city of Eboracum (modern York).[66] Eboracum and Deva Victrix (modern Chester) were the main legionary bases in the region, with other smaller forts including Mamucium (Manchester) and Cataractonium (Catterick).[67][68] Britannia Inferior extended as far north as Hadrian's Wall, which was the northernmost border of the Roman Empire.[lower-alpha 6] Although the Romans invaded modern-day Northumberland and part of Scotland beyond it, they never succeeded in conquering the reaches of Britain beyond the River Tyne.[69]

Anglo-Saxons and Vikings

After the end of Roman rule in Britain and the arrival of the Angles, Yr Hen Ogledd (the "Old North") was divided into rival kingdoms, Bernicia, Deira, Rheged and Elmet.[70] Bernicia covered lands north of the Tees, Deira corresponded roughly to the eastern half of modern-day Yorkshire, Rheged to Cumbria, and Elmet to the western-half of Yorkshire. Bernicia and Deira were first united as Northumbria by Aethelfrith, a king of Bernicia who conquered Deira around the year 604.[71] Northumbria then saw a Golden Age in cultural, scholarly and monastic activity, centred on Lindisfarne and aided by Irish monks.[72] The north-west of England retains vestiges of a Celtic culture, and had its own Celtic language, Cumbric, spoken predominately in Cumbria until around the 12th century.[73]

Parts of the north and east of England were subject to Danish control (the Danelaw) during the Viking era, but the northern part of the old Anglo-Saxon kingdom of Northumbria remained under Anglo-Saxon control.[lower-alpha 7] Under the Vikings, monasteries were largely wiped out, and the discovery of grave goods in Northern churchyards suggests that Norse funeral rites replaced Christian ones for a time.[75] Viking control of certain areas, particularly around Yorkshire, is recalled in the etymology of many place names: the thorpe in town names such as Cleethorpes and Scunthorpe, the kirk in Kirklees and Ormskirk and the by of Whitby and Grimsby all have Norse roots.[76]

Norman Conquest and the Middle Ages

The 1066 defeat of the Norwegian king Harald Hardrada by the Anglo-Saxon Harold Godwinson at the Battle of Stamford Bridge near York marked the beginning of the end of Viking rule in England, and the almost immediate defeat of Godwinson at the hands of the Norman William the Conqueror at the Battle of Hastings was in turn the overthrow of the Anglo-Saxon order.[77] The Northumbrian and Danish aristocracy resisted the Norman Conquest, and to put an end to the rebellion, William ordered the Harrying of the North. In the winter of 1069–1070, towns, villages and farms were systematically destroyed across much of Yorkshire as well as northern Lancashire and County Durham.[78][79] The region was gripped by famine and much of Northern England was deserted. Chroniclers at the time reported a hundred thousand deaths – modern estimates place the total somewhere in the tens of thousands, out of a population of two million.[78] When the Domesday Book was compiled in 1086, much of Northern England was still recorded as wasteland,[79] although this may have been in part because the chroniclers, more interested in manorial farmland, paid little attention to pastoral areas.[80]

.jpg)

Following Norman subjugation, monasteries returned to the North as missionaries sought to "settle the desert".[81] Monastic orders such as the Cistercians became significant players in the economy of Northern England – the Cistercian Fountains Abbey in North Yorkshire became the largest and richest of the Northern abbeys, and would remain so until the Dissolution of the Monasteries.[82] Other Cistercian abbeys are at Rievaulx, Kirkstall and Byland. The 7th-century Whitby Abbey was Benedictine and Bolton Abbey, Augustinian. A significant Flemish immigration followed the conquest, which likely populated much of the desolated regions of Cumbria, and which was persistent enough that the town of Beverley in the East Riding of Yorkshire still had an ethnic enclave called Flemingate in the thirteenth century.[83]

During the Anarchy, Scotland invaded Northern England and took much of the land north of the Tees. In the 1139 peace treaty that followed, Prince Henry of Scotland was made Earl of Northumberland and kept the counties of Cumberland, Westmorland and Northumbria, as well as part of Lancashire. These reverted to English control in 1157, establishing for the most part the modern England–Scotland border.[84] The region also saw violence during The Great Raid of 1322 when Robert the Bruce invaded and raided the whole of Northern England. There was also the Wars of the Roses, including the decisive Battle of Wakefield, although the modern-day conception of the war as a conflict between Lancashire and Yorkshire is anachronistic – Lancastrians recruited from across Northern England, including Yorkshire, while the Yorkists drew most of their power from Southern England, Wales and Ireland.[85] The Anglo-Scottish Wars also touched the region, and in just 400 years, Berwick-upon-Tweed – now the northernmost town in England – changed hands more than a dozen times.[86] The wars also saw thousands of Scots settle south of the border, chiefly in the border counties and Yorkshire.[87]

Early modern era

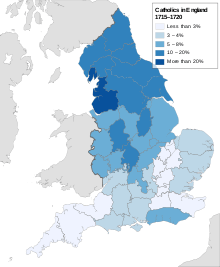

After the English Reformation, the North saw several Catholic uprisings, including the Lincolnshire Rising, Bigod's Rebellion in Cumberland and Westmorland, and largest of all, the Yorkshire-based Pilgrimage of Grace, all against Henry VIII.[88] His daughter Elizabeth I faced another Catholic rebellion, the Rising of the North.[89] The region would become the centre of recusancy as prominent Catholic families in Cumbria, Lancashire and Yorkshire refused to convert to Protestantism.[90] Royal power over the region was exercised through the Council of the North at King's Manor, York, which was founded in 1484 by Richard III. The Council existed intermittently for the next two centuries – its final incarnation was created in the aftermath of the Pilgrimage of Grace and was chiefly an institution for providing order and dispensing justice.[91]

Northern England was a focal point for fighting during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. The border counties were invaded by Scotland in the Second Bishops' War, and at the 1640 Treaty of Ripon King Charles I was forced to temporarily cede Northumberland and County Durham to the Scots and pay to keep the Scottish armies there.[92] To raise enough funds and ratify the final peace treaty, Charles had to call what became the Long Parliament, beginning the process that led to the First English Civil War. In 1641, the Long Parliament abolished the Council of the North for perceived abuses during the Personal Rule period.[91] By the time war broke out in 1642, King Charles had moved his court to York, and Northern England was to become a major base of the Royalist forces until they were routed at the Battle of Marston Moor.[93]

Industrial Revolution

At the beginning of the Industrial Revolution, Northern England had plentiful coal and water power while the poor agriculture in the uplands meant that labour in the area was cheap. Mining and milling, which had been practiced on a small scale in the area for generations, began to grow and centralise.[94] The boom in industrial textile manufacture is sometimes attributed to the damp climate and soft water making it easier to wash and work fibres, although the success of Northern fabric mills has no single clear source.[30] Readily available coal and the discovery of large iron deposits in Cumbria and Cleveland allowed ironmaking and, with the invention of the Bessemer process, steelmaking to take root in the region. High quality steel in turn fed the shipyards that opened along the coasts, especially on Tyneside and at Barrow-in-Furness.[95]

The Great Famine in Ireland of the 1840s drove migrants across the Irish Sea, and many settled in the industrial cities of the North, especially Manchester and Liverpool – at the 1851 census, 13% of the population of Manchester and Salford were Irish-born, and in Liverpool the figure was 22%.[96] In response there was a wave of anti-Catholic riots and Protestant Orange Orders proliferated across Northern England, chiefly in Lancashire, but also elsewhere in the North. By 1881 there were 374 Orange organisations in Lancashire, 71 in the North East, and 42 in Yorkshire.[97][98] From further afield, Northern England saw immigration from European countries such as Germany, Italy, Poland, Russia and Scandinavia. Some immigrants were well-to-do industrialists seeking to do business in the booming industrial cities, some were escaping poverty, some were servants or slaves, some were sailors who chose to settle in the port towns, some were Jews fleeing pogroms on the continent, and some were migrants originally stranded at Liverpool after attempting to catch an onwards ship to the United States or to colonies of the British Empire.[99][100][101] At the same time, hundreds of thousands from depressed rural areas of the North emigrated, chiefly to the US, Canada, South Africa, Australia and New Zealand.[101][102][103]

Deindustrialisation and modern history

.jpg)

The First World War was the turning point for the economy of Northern England. In the interwar years, the Northern economy began to be eclipsed by the South – in 1913–1914, unemployment in "outer Britain" (the North, plus Scotland and Wales) was 2.6% while the rate in Southern England was more than double that at 5.5%, but in 1937 during the Great Depression the outer British unemployment rate was 16.1% and the Southern rate was less than half that at 7.1%.[104] The weakening economy and interwar unemployment caused several episodes of social unrest in the region, including the 1926 general strike and the Jarrow March. The Great Depression highlighted the weakness of Northern England's specialised economy: as world trade declined, demand for ships, steel, coal and textiles all fell.[105] For the most part, Northern factories were still using nineteenth-century technology, and were not able to keep up with advances in industries such as motors, chemicals and electricals, while the expansion of the electric grid removed the North's advantages in terms of power generation and meant it was now more economic to build new factories in the Midlands or South.[106]

The industrial concentration in Northern England made it a major target for Luftwaffe attacks during the Second World War. The Blitz of 1940–1941 saw major raids on Barrow-in-Furness, Hull, Leeds, Manchester, Merseyside, Newcastle and Sheffield with thousands killed and significant damage to the cities. Liverpool, a vital port for supplies from North America, was especially hard hit – the city was the most bombed in the UK outside London, with around 4,000 deaths across Merseyside and most of the city centre destroyed.[107] The rebuilding that followed, and the simultaneous slum clearance that saw whole neighbourhoods demolished and rebuilt, transformed the faces of Northern cities.[108] Immigration from the "New Commonwealth", especially Pakistan and Bangladesh, starting in the 1950s reshaped Northern England once more, and there are now significant populations from the Indian subcontinent in towns and cities such as Bradford, Leeds, Preston and Sheffield.[109]

Deindustrialisation continued and unemployment gradually increased during the 1970s, but accelerated during the government of Margaret Thatcher, who chose not to encourage growth in the North if it risked growth in the South.[110][111] The era saw the 1984–85 miners' strike, which brought hardship for many Northern mining towns. Northern metropolitan county councils, which were Labour strongholds often with very left-wing leadership (such as Militant-dominated Liverpool and the so-called "People's Republic of South Yorkshire"), had high-profile conflicts with the national government. The increasing awareness of the North–South divide strengthened the distinct Northern English identity, which, despite regeneration in some of the major cities, remains to this day.[110]

The region saw several IRA attacks during the Troubles, including the M62 coach bombing, the Warrington bomb attacks and the 1992 and 1996 Manchester bombings. The latter was the largest bomb detonation in Great Britain since the end of the Second World War, and damaged or destroyed much of central Manchester.[112] The attack led to Manchester's ageing infrastructure being rebuilt and modernised, sparking the regeneration of the city and making it a leading example of post-industrial redevelopment followed by other cities in the region and beyond.[113][114]

Demographics

As of the 2011 census, Northern England had a population of 14,933,000 – a growth of 5.1% since 2001 – in 6,364,000 households, meaning that Northerners comprise 28% of the English population and 24% of the UK population. Taken overall, 8% of the population of Northern England were born overseas (3% from the European Union including Ireland and 5% from elsewhere), substantially less than the England and Wales average of 13%, and 5% define their nationality as something other than a UK or Irish identity.[lower-alpha 8] [115][116][117] 90.5% of the population described themselves as white, compared to an England and Wales average of 85.9%; other ethnicities represented include Pakistani (2.9%), Indian (1.3%), Black (1.3%), Chinese (0.6%) and Bangladeshi (0.5%). The broad averages hide significant variation within the region: Allerdale and Redcar and Cleveland had a greater percentage of the population identifying as White British (97.6% each) than any other district in England and Wales, while Manchester (66.5%), Bradford (67.4%) and Blackburn with Darwen (69.1%) had among the lowest proportions of White British outside London.[118][119]

Languages

.jpg)

95% of the Northern population speak English as a first language – compared to an England and Wales average of 92%[lower-alpha 9] – and another 4% speak English as a second language well or very well.[52][120] The 5% of the population who have another native language are chiefly speakers of European or South Asian languages. As of the 2011 census, the largest languages apart from English were Polish (spoken by 0.7% of the population), Urdu (0.6%) and Punjabi (0.5%), and 0.4% of the population speak a variety of Chinese: a similar distribution to that in the whole of England.[120] Redcar and Cleveland has the largest proportion of the population speaking English as a first language in England, with 99.3%.[52]

Religion

At the 2011 census, the North East and North West had the largest proportion of Christians in England and Wales; 67.5% and 67.3% respectively (the proportion in Yorkshire and the Humber was lower at 59.5%). Yorkshire and the Humber and the North West both had significant populations of Muslims – 6.2% and 5.1% respectively – while Muslims in the North East made up only 1.8% of the population. All other faiths combined comprised less than 2% of the population in all regions.[121]

The census question on religion has been criticised by the British Humanist Association as leading, and other surveys of religion tend to find very different results.[122] The 2015 British Election Survey found 52% of Northerners identified as Christian (22% Anglican, 14% non-denominational Christian, 12% Roman Catholic, 2% Methodist, and 2% other Christian denominations), 40% as non-religious, 5% as Muslim, 1% as Hindu and 1% as Jewish.[123]

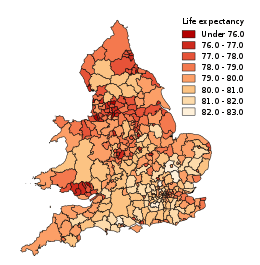

Health

One major manifestation of the North–South divide is in health and life expectancy statistics.[124] All three Northern England statistical regions have lower than average life expectancies and higher than average rates of cancer, circulatory disease and respiratory disease.[125][126] Blackpool has the lowest life expectancy at birth in England – male life expectancy at birth between 2012 and 2014 was 74.7, against an England-wide average of 79.5 – and the majority of English districts in the bottom 50 were in the North East or the North West. However, regional differences do seem to be slowly narrowing: between 1991 and 1993 and 2012–2014, life expectancy in the North East increased by 6.0 years and in the North West by 5.8 years, the fastest increases in any region outside London, and the gap between life expectancy in the North East and South East is now 2.5 years, down from 2.9 in 1993.[126]

These health inequalities manifested during the COVID-19 pandemic in high infection rates, death rates and excess mortality in Northern England, and in severe job losses in the following Great Lockdown recession.[127] By June 2020, the infection rate in Northern England was nearly double that in London,[128] and a study by the Northern Health Science Alliance found that of the six worst affected areas in England during the pandemic in their study, five were located in the North.[127]

Education

Before the 19th century there were no universities in Northern England. The first was the University of Durham, founded in 1832 and sometimes counted with the ancient universities of Oxford and Cambridge, although it post-dates them by many centuries.[129] The next universities built in the North were part of the wave of redbrick universities of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Today, there are seven Northern institutions in the Russell Group of leading research universities: Durham, the redbricks of Leeds, Liverpool, Manchester, Newcastle and Sheffield and the later plate glass university of York. These universities, together with plate-glass Lancaster, form the N8 Research Partnership.[130]

There is a significant attainment gap between Northern and Southern schools, and pupils in the three Northern regions are less likely than the national average to achieve five higher-tier GCSEs,[131] although this may be down to economic disadvantages faced by Northern pupils rather than an actual difference in school quality.[132] Northern students are under-represented at Oxbridge, where three times as many places go to Southerners as to Northerners, and other Southern universities while Southerners are under-represented at leading Northern universities such as Sheffield, Manchester and Leeds.[133] There are calls for the government to invest in education in disadvantaged parts of Northern England to redress this.[134]

Economy

Like the UK as a whole, the Northern English economy is now dominated by the service sector – as of September 2016, 82.2% of workers in the Northern statistical regions were employed in services, compared to 83.7% for the UK as a whole. Manufacturing now employs 9.5%, compared to the national average of 7.6%.[135] The unemployment rate in Northern England is 5.3% compared to an England-wide and UK-wide average of 4.8%, and the North East has the highest unemployment rate in the UK, at 7.0% as of December 2016, more than one percentage point higher than any other region.[136][137] As of 2015, the gross value added (GVA) of the Northern English economy was £316 billion,[138] and if it were an independent nation, it would be the tenth largest economy in Europe.[139] The region does have poor growth and productivity rates compared to Southern England and to other EU countries.[140]

Growth, employment and household income have lagged behind the South, and the five most deprived districts in England[lower-alpha 10] are all in Northern England,[141][142] as are ten of the twelve most declining major towns in the UK.[lower-alpha 11][143] The picture is not clear-cut, as the North has areas which are as wealthy as, if not wealthier than, fashionable Southern areas such as Surrey. Yorkshire's Golden Triangle which extends from north Leeds to Harrogate and across to York is an example, as is Cheshire's Golden Triangle, centred on Alderley Edge.[144][145] There are major disparities even across individual cities: Sheffield Hallam is one of the wealthiest constituencies in the country, and is the richest outside London and the South East, while Sheffield Brightside and Hillsborough, just on the other side of the city, is one of the most deprived.[144][146] Housing in Northern England is more affordable than the UK average: the median house price in most Northern cities was below £200,000 in 2015 with typical increases of below 10% over the previous five years. However, some areas have seen house prices fall considerably, putting inhabitants at risk of negative equity.[147][148]

To stimulate the Northern economy, the government has organised a series of programmes to invest in and develop the region, of which the latest as of 2017 is the Northern Powerhouse. The North has also been a significant recipient of European Union Structural Funds. Between 2007 and 2013, EU funds created around 70,000 jobs in the region, and the majority of Northern Powerhouse funding comes from the European Regional Development Fund and the European Investment Bank.[149] The loss of these funds following Brexit, combined with potential reductions in exports to the EU, has been identified as a threat to Northern growth.[150][151]

Public sector

The public sector is a major employer in Northern England. Between 2000 and 2008, the majority of new jobs created in Northern England were for the government and its suppliers and contractors.[152] All three Northern regions have public sector employment above the national average, and North East has the highest level in England with 20.2% of the workforce in the public sector as of 2016 – down from 23.4% a decade earlier.[153][154] The austerity programme under the government of David Cameron saw significant cuts to public services, and the reduction in public sector employment resulted in job losses for around 3% of the Northern England workforce with significant impact on the regional economy.[152]

Agriculture and fisheries

There are 2,580,000 hectares (6,400,000 acres; 25,800 km2; 10,000 sq mi) of farmland in Northern England.[155] The rough Pennine terrain means that most of Northern England is unsuited for growing crops; like Scotland, Northern farming was traditionally dominated by oats, which grow better than wheat in poor soil.[156][157] Today, the mix of cereals and vegetables grown is similar to that of the UK as a whole, but only a minority of land is arable. Only 32% of Northern farmland is primarily used for growing crops, compared to 49% for England as a whole. Conversely, 57% of the land is given over to rearing livestock, and 33% of England's cattle, 43% of its pigs and 46% of its sheep and lambs are reared in the North.[155]

The only part of the region that is predominantly given over to crops is the land around the Humber estuary, where the well-drained fens result in excellent quality land.[19][156] The lowland Cheshire Plain is mostly given over to dairy farming, while in the Pennines and Cheviots grazing sheep play an important role not just in agriculture but also in land management more generally.[156] Heather moorland in the Pennine uplands is home to driven grouse shooting from 12 August (the Glorious Twelfth) until 10 December every year. The number of grouse moors in Northern England is a major threat to natural predators, which are often killed by gamekeepers to protect grouse, and as a result the Cumbria Wildlife Trust describes the North's moors as a "black hole" for the endangered hen harrier.[158]

Sea fishing is an important industry for Northern coastal towns. Major fishing ports include Fleetwood, Grimsby, Hull and Whitby. At its height, Grimsby was the largest fishing port in the world, but the Northern fishing industry suffered greatly from a series of events in the second half of the twentieth century: the Cod Wars with Iceland and establishment of the exclusive economic zone ended British access to rich North Atlantic fishing grounds, while the North Sea was badly overfished and the European Common Fisheries Policy put strict quotas on catches to protect the almost depleted stocks.[159][160] Grimsby is now transitioning to the processing of imported seafood and to offshore wind to replace its fishing fleet.[160]

Manufacturing and energy

Northern England has a strong export-based economy, with trade more balanced than the UK average, and the North East is the only region of England to regularly export more than it imports.[161][162] Chemicals, vehicles, machinery and other manufactured goods make up the majority of Northern exports, just over half of which go to other EU countries.[162] Major manufacturing plants include car plants at Vauxhall Ellesmere Port, Jaguar Land Rover Halewood and Nissan Sunderland, the Leyland Trucks factory, the Hitachi Newton Aycliffe train plant, the Humber, Lindsey and Stanlow oil refineries, the NEPIC cluster of chemical works based around Teesside, and the nuclear processing facilities at Springfields and Sellafield.[163]

Offshore oil and gas from North Sea and Irish Sea, and more recently offshore wind power, are significant components in Northern England's energy mix.[164] Although deep-pit coal mining in the UK ended in 2015 with the closure of Kellingley Colliery, North Yorkshire, there are still several open-pit mines in the area.[165] Shale gas is especially prevalent across Northern England, although plans to extract it through hydraulic fracturing ("fracking") have proven to be controversial.[166]

Retail and services

Around 10% of the Northern England workforce is employed in retail.[168] Of the Big Four supermarkets in the UK, two – Asda and Morrisons – are based in the North. Northern England was the birthplace of the modern cooperative movement, and the Manchester-based Co-operative Group has the highest revenue of any firm in the North West.[169][170] The area is also home to many online retailers, with startups emerging around tech hubs in Northern cities.[171][172]

With urban regeneration, high-value service sector industries such as corporate services and financial services have taken root in Northern England, with major hubs around Leeds and Manchester.[168] Call centres – attracted by low labour costs and a preference for Northern English accents among the public – have replaced heavy industry as major employers of unskilled workers, with more than 5% of workers in all Northern England regions working in one.[173][174]

High-tech and research

Together, the N8 research universities have over 190,000 students and contribute more to the Northern economy in terms of GVA than agriculture, car manufacturing or media.[130] Discoveries and inventions at these universities have resulted in spin-offs worth hundreds of millions to local economies: the discovery of graphene at the University of Manchester produced the National Graphene Institute and the Sir Henry Royce Institute for Advanced Materials, while robotics research at the University of Sheffield led to the development of the Advanced Manufacturing Park.[172]

Recent decades have seen the growth of high-tech companies based around Northern England's major cities. There are eleven high-tech firms worth over $1 billion based in the region, and digital industries support around 300,000 jobs.[172][175] Game development, online retail, health technology and analytics are among the major high-tech sectors in the North.[172][176]

Leisure and tourism

The expansion of the railway network in the second half of the nineteenth century meant most in the North lived within reach of the coast, and seaside towns saw a major tourism boom. By around 1870 Blackpool on the Lancashire coast had become overwhelmingly the most popular destination – not just for Northern families, but many from the Midlands and Scotland as well.[177] Other resorts popular with Northerners included Morecambe in northern Lancashire, Whitley Bay near Newcastle, Whitby in North Yorkshire, and New Brighton on the Wirral Peninsula, as well as Rhyl over the border in North Wales.[178][179]

The same social forces that had built these resorts in the nineteenth century proved to be their undoing in the twentieth. Transport links continued to improve and it became possible to travel overseas quickly and affordably. The Belgian coast at Ostend became popular with Northern working-class tourists in the first half of the twentieth century, and the introduction of package holidays in the 1970s was the death of most Northern seaside resorts.[180] Blackpool has maintained a focus on tourism, and remains one of the most visited towns in England, but visitor numbers are far below their peak and the town's economy has suffered – both employment rates and average earnings remain below the regional average.[181]

The wild landscapes of the North are a major draw for tourists,[182] and many urban areas are looking for regeneration through industrial, heritage and cultural tourism: of the 24 national museums and galleries in England outside London, 14 are located in the North.[183] As of 2015, Northern England receives around a quarter of all domestic tourism within the UK, with 28.7 million visitors in 2015, but only 8% of international tourists to the United Kingdom visit the region.[184][185]

Media

Television

As part of a drive to reduce media centralisation in London, the BBC and ITV have moved much of their programme production to MediaCityUK in Salford and Channel 4 has moved its headquarters to Leeds. Of the four national evening soap operas, three are set and filmed in Northern England (Coronation Street in Manchester, Emmerdale in the Yorkshire Dales and Hollyoaks in Chester) and these are important to the local TV industry – the commitment to Emmerdale saved ITV Yorkshire's Leeds Studios from closure.[186][187] The region also has a reputation for drama serials and has produced some the most successful and acclaimed series of recent decades, including Boys from the Blackstuff, Our Friends in the North, Clocking Off, Shameless and Last Tango in Halifax.[188][189]

Newspapers

Since The Guardian (formerly The Manchester Guardian) moved to London in 1964, no major national paper is based in the North, and Northern news stories tend to be poorly covered in the national press.[190][191] The Yorkshire Post promotes itself as "Yorkshire's national paper" and covers some national and international stories, but is primarily focused on news from Yorkshire and the North East.[192] An attempt in 2016 to create a dedicated North-focused national newspaper, 24, failed after six weeks.[193] Across Northern England as a whole, The Sun is the best selling newspaper, but the ongoing boycott around Merseyside following the newspaper's coverage of the 1989 Hillsborough disaster has seen the paper fall behind both the Daily Mail and the Daily Mirror in the North West.[194][195][196] In general national readership in the North drags behind that of the South; the Mirror and the Daily Star are the only national papers with more readers in Northern England than in the South East and London.[190] Local newspapers are the top-selling titles in both the North East and Yorkshire and the Humber, although Northern regional newspapers have seen steep declines in readership in recent years.[196][197] Only seven daily Northern papers have circulation figures above 25,000 as of June 2016: Manchester Evening News, Liverpool Echo, Hull Daily Mail, Newcastle Chronicle, The Yorkshire Post and The Northern Echo.[197]

Communications and the internet

.jpg)

Manchester Network Access Point is the only internet exchange point in the UK outside London, and forms the main hub for the region.[198] Household internet access in Northern England is at or above the UK average, but speeds and broadband penetration vary greatly.[199][200] In 2013 the average speed in central Manchester was 60 Mbit/s, while in nearby Warrington the average speed was only 6.2 Mbit/s.[201] Hull, which is unique in the UK in that its telephone network was never nationalised, has simultaneously some of the fastest and slowest internet speeds in the country: many households have "ultrafast" fibre optic broadband as standard, but it is also one of only two places in the UK where over 30% of businesses receive less than 10 Mbit/s.[202] Speeds are especially poor in the rural parts of the North, with many small towns and villages completely without high speed access. Some areas have therefore formed their own community enterprises, such as Broadband 4 Rural North in Lancashire and Cybermoor in Cumbria, to install high-speed internet connections. Mobile broadband coverage is similarly patchy, with 3G and 4G almost universal in cities but unavailable in large parts of Yorkshire, the North East and Cumbria.[203]

Culture and identity

The individual regions of the North have had their own identities and cultures for centuries, but with industrialisation, mass media and the opening of the North–South divide, a common Northern identity began to develop. This identity was initially a reactionary response to Southern prejudices—the North of the nineteenth century was largely depicted as a dirty, wild and uncultured place, even in sympathetic depictions such as Elizabeth Gaskell's 1855 novel North and South[204]—but became an affirmation of what Northerners saw as their own personal strengths.[205][206][207] Traits stereotypically associated with Northern England are straight-talking, grit and warmheartedness, as compared to the supposedly effete Southerners.[205][208] Northern England—especially Lancashire, but also Yorkshire and the North East—has a tradition of matriarchal families, where the woman of the house runs the home and controls the family's finances. This too has its roots in industrialisation, when mills offered well-paid work for women: during depressions when demand for coal and steel were low, women were often the main breadwinners. Northern women are still stereotyped as strong-willed and independent, or affectionately as battle-axes.[209][210][211]

Clothing

The North of England is often stereotypically represented through the clothing worn by working-class men and women in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.[212] Working men would wear a heavy jacket and trousers held up by braces, an overcoat, and a hat, typically a flat cap, while women would wear a dress, or a skirt and blouse, with an apron on top as protection from dirt; in colder months they would often wear a shawl or headscarf.[212][213][214] The maud, a woollen plaid woven in a pattern of small black and white checks, was also popular in Northern England until the early twentieth century.[215]

If not wearing leather lace-up shoes, some men and women would have worn English clogs, which were hardwearing and had replaceable soles and tips.[214] Factory workers tapping their feet in time with the click of machinery developed a type of folk clog dance referred to as clogging, which was intricately developed in the North.[216]

In the second half of the twentieth century, these traditional clothes fell out of fashion. Other styles such as "casual clobber" (mainland European designer clothing brought back by touring football fans) and sportswear became more popular, and the influence of Northern bands and football teams helped spread them across the country.[217][218] In the twenty-first century, some traditional Northern items of clothing have begun to make a comeback – in particular, the flat cap.[212][219]

Cuisine

Impressions of Northern English cuisine are still shaped by the working-class diet of the early twentieth century, which was heavy on offal, high in calories and often not particularly healthy. Dishes such as black pudding, tripe, mushy peas and meat pie remain stereotypical Northern English foods in the national imagination. As a result, there is a concerted effort among Northern chefs to improve the region's image.[220] Some Northern dishes such as Yorkshire pudding and Lancashire hotpot have spread across the UK, and only their names now hint at their origin. Among the Northern delicacies that have achieved Protected Geographical Status are traditional Cumberland sausage, traditional Grimsby smoked fish, Swaledale cheese, Yorkshire forced rhubarb and Yorkshire Wensleydale.[lower-alpha 12] [222]

The North is known for its often crumbly cheeses, of which Cheshire cheese is the earliest example. Unlike Southern cheeses like Cheddar, Northern cheeses typically use uncooked milk and a pre-salted curd pressed under enormous weights, resulting in a moist, sharp-tasting cheese.[223] Wensleydale, another crumbly cheese, is unusual in that it is often served as a side to sweet cakes,[224] which are themselves well represented in Northern England. Parkin, an oatmeal cake with black treacle and ginger, is a traditional treat across the North on Bonfire Night,[225] and the fruity scone-like singing hinny and fat rascal are popular in the North East and Yorkshire respectively.[226]

While a variety of beers are popular across Northern England, the region is especially associated with brown ales such as Newcastle Brown Ale, Double Maxim and Samuel Smith's Nut Brown Ale.[227] Beer in the North is usually served with a thick head which accentuates the nutty, malty flavours preferred in Northern beers.[228] On the non-alcoholic side, the North – in particular, Lancashire – was the hub of the temperance bar movement which popularised soft drinks such as dandelion and burdock, Tizer and Vimto.[229][230]

Greggs, the bakery chain, is an integral part of Northern cuisine and Northern identity. The number of people per Greggs has been cited as a key indicator as to whether a town should be considered Northern.[231]

In recent decades, immigration to Northern England has shaped its cuisine. The Teesside parmo is one example, derived from escalope Parmesan brought to the area by an Italian-American immigrant and adapted to the region's taste.[232] There are large Chinatowns in Liverpool, Manchester and Newcastle, and communities from the Indian subcontinent in all major towns.[220] Bradford has won the Federation of Specialist Restaurant's "Curry Capital" title six years in a row as of 2016,[233] while the Curry Mile in Manchester formerly had the largest concentration of curry restaurants in the UK and now offers a wide range of South Asian and Middle Eastern cuisine.[234]

Literature

_(cropped).jpg)

The contrasting geography of Northern England is reflected in its literature. On the one hand, the wild moors and lakes have inspired generations of Romantic authors: the poetry of William Wordsworth and the novels of the Brontë sisters are perhaps the most famous examples of writing inspired by these elemental forces. Classics of children's literature such as The Railway Children (1906), The Secret Garden (1911) and Swallows and Amazons (1930) portray these largely untouched landscapes as worlds of adventure and transformation where their protagonists can break free of the restrictions of society.[235] Modern poets such as the Poet Laureates Ted Hughes and Simon Armitage have found inspiration in the Northern countryside, producing works that take advantage of the sounds and rhythms of Northern English dialects.[236][237]

Meanwhile, the industrialising and urbanising cities of the North gave rise to many masterpieces of social realism. Elizabeth Gaskell was the first in a lineage of female realist writers from the North that later included Winifred Holtby, Catherine Cookson, Beryl Bainbridge and Jeanette Winterson.[238] Many of the angry young men of post-war literature were Northern, and working-class life in the face of deindustrialisation is depicted in novels such as Room at the Top (1959), Billy Liar (1959), This Sporting Life (1960) and A Kestrel for a Knave (1968).[236][239]

Music

Traditional folk music in Northern England is a combination of styles of England and Scotland – what is now called the Anglo-Scottish border ballad was once prevalent as far south as Lancashire.[240] In the Middle Ages, much of Northern folk was accompanied by bagpipes, with styles including the Lancashire bagpipe, Yorkshire bagpipe and Northumbrian smallpipes. These disappeared in the early nineteenth century from the industrialising south of the region, but remain in the music of Northumbria.[241] The British brass band tradition began in Northern England at around the same time: the dismissal of the Cheshire, Lancashire and Yorkshire military bands after the Napoleonic Wars, combined with the desire of industrial communities to better themselves, led to the founding of civilian bands. These bands provided entertainment at community events and led protest marches during the era of radical agitation.[242] Although the style has since spread across much of Great Britain, brass bands remain a stereotype of the North, and the Whit Friday brass band contests draw hundreds of bands from across the UK and further afield.[242][243]

Northern England also has a thriving popular music scene. Influential movements include Merseybeat from the Liverpool area, which produced The Beatles, Northern soul, which brought Motown to England, and Madchester, the precursor to the rave scene.[244][245] Across the Pennines, Sheffield is the birthplace of influential electronic pop bands from Cabaret Voltaire to Pulp, the New Yorkshire indie rock movement of the 2000s gave the country the Kaiser Chiefs and the Arctic Monkeys, and Teesside has a rock scene stretching from Chris Rea to Maxïmo Park.[246][247][248] The press frequently frames music stories and reviews in terms of cultural and class differences between North and South, notably in the 1960s rivalry between the Beatles and the Rolling Stones and the 1990s Battle of Britpop between Oasis and Blur.[249][248]

Sport

Sport has been both one of the most unifying cultural forces in Northern England and, thanks to local rivalries such as the Lancashire–Yorkshire Roses rivalry, one of the most divisive. As huge numbers of people moved into recently built cities with little cultural heritage, local sports teams offered the population a sense of place and identity that was otherwise absent.[250]

Many early Northern sports players were working class and needed to miss work to play, with their teams compensating them for lost wages. By contrast, Southern teams, drawing from the traditions of public schools and Oxbridge, put great emphasis on amateurism and the Southern-dominated governing bodies forbade payments to players. This tension shaped the sports of association football and cricket, and led to the schism between the two main forms of rugby. The North is also associated with the animal sports of dog racing with whippets, pigeon racing and ferret legging, although these are now far more popular in stereotype than in reality.[251][252]

Manchester hosted the 2002 Commonwealth Games, which left it a legacy of sporting facilities including the City of Manchester Stadium, Manchester Aquatics Centre and the National Cycling Centre, headquarters of British Cycling.[253] The Grand Départ for the 2014 Tour de France was in Leeds, and every year since Yorkshire has hosted the Tour de Yorkshire cycling event, part of the UCI Europe Tour.[254] Tyneside meanwhile hosts the Great North Run, the UK's biggest mass-participation sporting event and the most popular half marathon in the world.[255]

Football

The first football club in the UK was Sheffield F.C., founded in 1857. Early Northern football teams tended to adopt the Sheffield Rules rather than the Football Association Rules, but the two codes were merged in 1877. Many of the innovations of Sheffield Rules are now part of the global game, including corners, throw-ins, and free kicks for fouls.[256]

In 1883 Blackburn Olympic, a team composed mainly of factory workers, became the first Northern team to win the FA Cup, and the next year Preston North End won an FA Cup match against London-based Upton Park.[257][258] Upton Park protested that Preston had broken FA rules by paying their players. In response, Preston withdrew from the competition and fellow Lancashire clubs Burnley and Great Lever followed suit. The protest gathered momentum to the point where more than 30 clubs, predominantly from the North, announced that they would set up a rival British Football Association if the FA did not permit professionalism.[257] A schism was avoided in July 1885 when professionalism was formally legalised in English football.[258][259] The Football League was founded in 1888, and marked its independence from the London-based Football Association (FA) by establishing headquarters in Preston – the League retained a Northern identity even after it accepted several Southern teams into its ranks.[260] Organised women's football followed as the workforces of majority-female factories of Northern England in the First World War entered the 1917–18 Tyne, Wear & Tees Munition Girls Cup – the world's first women's football tournament. However, the FA did not support women's football and banned it altogether in 1921.[261] Intense local derbies between neighbouring teams mean that there is less of a North–South rivalry than in some other sports.[250]

.jpg)

Many of the powerhouses of English football came from the North – as of the 2019–20 season, of the 122 top-flight league titles since 1888, 82 (67%) have been won by teams based north of Crewe.[262] Everton, Liverpool, Manchester United and Manchester City are among the mainstays of the Premier League, while teams like Blackburn Rovers, Middlesbrough, Newcastle United and Sunderland have had more inconsistent runs in recent years, regularly being promoted and relegated from the top flight.[262] Northern England is also the birthplace of the largest proportion the country's top players – as of Euro 2016, 537 Northerners had played for the England team, compared to 266 Midlanders and 367 Southerners,[263] and 15 of the 23 man squad for the 2018 World Cup, as well as 14 of the 2019 Women's World Cup squad, were born in the region.[264]

Rugby

The Rugby Football Union, which enforced amateurism, suspended teams who compensated their players for missed work and injury, leading teams from Lancashire, Yorkshire and surrounding areas to split away in 1895 and form the Rugby Football League. Over time, the RFU and RFL adopted different rules and the two forms of the game – rugby union and rugby league – diverged. Rugby league's stronghold remains Northern England along the "M62 corridor" between Liverpool and Hull.[265] As of the 2020 season, 10 of the 12 teams in the Super League (the highest level of rugby league in the Northern Hemisphere) are from Northern England, with one team from Canada and one from France, and the 14-team Championship below it has 12 Northern teams, one London team and 1 French team.[266]

Rugby union was not entirely driven from Northern England, and in the 1970s the region was home to several strong teams.[267] The high-water mark of rugby union in Northern England was the 1979 New Zealand tour during which the English Northern Division was the only team to defeat the All Blacks.[268] In the 21st century the region's club sides have become less popular, with association football, cricket and rugby league attracting more spectators and talent.[267] In the 2019–20 season, Sale Sharks are the only Northern team left in the English Premiership, and Newcastle Falcons, Yorkshire Carnegie and Doncaster R.F.C. play in the RFU Championship.[269]

Cricket

Cricket has a strong following in Northern England, and three counties are represented by first-class county cricket teams: Durham, Lancashire and Yorkshire. The Roses Match (named for the Red Rose of Lancaster and the White Rose of York) between Lancashire and Yorkshire is one of the hardest fought rivalries in the sport – the pride of both sides, and their determination not to lose, resulted in the teams developing a slow, stubborn and defensive style that proved unpopular elsewhere in the country.[270] The London-based Marylebone Cricket Club, which controlled the game at the time, selected few Northern players for Test matches, and this was perceived as a snub to their playing style – the anger united Lancashire and Yorkshire against the South and helped cast a shared Northern identity that transcended the Roses rivalry.[270][271] This divide was illustrated in the 1924 County Championship, when Yorkshire beat London-based Middlesex to claim the title. Surrey accused Yorkshire of scuffing the pitch and intimidating the bowlers, while the match with Middlesex was so vicious that the team threatened to never play in Yorkshire again.[270][271] The Lancashire captain Jack Sharp on the other hand was quoted as saying "I'm real glad a rose won it. Red or white, it doesn't matter."[271] Durham are a recent addition to top-flight cricket, having only achieved first-class status in 1992, but have won the County Championship three times.[272]

Although Yorkshire and Lancashire were traditionally more relaxed about professionalism than other counties, cricket did not see the same regional schisms on the topic that rugby and football did – there were debates over amateur status in first-class cricket, but these tensions were given release in the Gentlemen v Players fixture.[273] Nevertheless, the annual North v South games were among the most popular and competitive in the sport, running annually from 1849 until 1900 and intermittently thereafter.[274]

Politics

Northern England, as the first area in the world to industrialise, was the birthplace of much modern political thought. Marxism and, more generally, socialism were shared by reports into the lives of the Northern working class, from Friedrich Engels' The Condition of the Working Class in England to George Orwell's The Road to Wigan Pier.[275] Meanwhile, enterprise and trade at the North's ports influenced the birth of Manchester Liberalism, a laissez-faire free trade philosophy. Expounded by C. P. Scott and the Manchester Guardian, the movement's greatest success was the repeal of the Corn Laws, protests against which had led to the 1819 Peterloo Massacre in Manchester.[276]

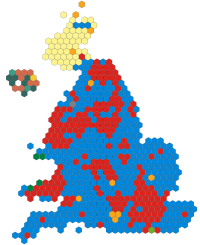

The first Trades Union Congress was held in Manchester in 1868,[278] and as of 2015 trade union membership in Northern England remained higher than in Southern England, although it is lower than in the other Home Nations.[279] Since the Thatcher era, the Conservative Party struggled to gain support in the area.[17][110][280] Today, Northern England is generally described as a stronghold of the Labour Party – although the Conservatives hold some rural seats, they traditionally held almost no urban seats and as of the 2016 local elections there are no Conservative councillors on Liverpool City Council, Manchester City Council, Newcastle City Council or Sheffield City Council.[17] During the 2019 general election, many traditionally Labour constituencies in Northern England swung heavily towards the Conservatives, and the collapse of the "red wall" of Northern Labour seats was a major factor in the Conservative victory.[281] Historically the region was also a heartland for the Liberals, and between the 1980s and the 2010s their successors in the Liberal Democrats benefited from Conservative unpopularity by positioning themselves as the centrist alternative to Labour in the North.[282][283]

At the 2016 EU membership referendum, all three Northern England regions voted to leave, as did all English regions outside London. The largest Northern Remain vote was 60.4% in Manchester; the largest Leave vote was 69.9% in North East Lincolnshire.[284] In total, the Leave vote in the Northern England regions was 55.9% – higher than in the Southern England regions and the other Home Nations, but lower than in the Midlands or the East of England.[284] The Eurosceptic UK Independence Party (UKIP) positioned themselves as the main challenger to Labour in Northern constituencies, and came second in many at the 2015 general election.[285][286] UKIP originally struggled in the region due to vote splitting with the far-right British National Party (BNP), who exploited racial tensions in the wake of the 2001 Bradford riots and other riots in Northern towns. In 2006, 40% of BNP voters lived in Northern England and both BNP MEPs elected at the 2009 European elections came from Northern constituencies.[287][288] After 2013, BNP support in the region collapsed as most voters swung to UKIP.[289] The Northern UKIP vote in turn collapsed following the EU referendum, with most UKIP voters returning to their former allegiances.[290]

Campaigns for regional autonomy for the North have seen little electoral support. Plans by Labour under Tony Blair to create devolved regional assemblies for the three Northern regions were abandoned after the government lost the 2004 North East England devolution referendum against a No vote of 78%.[291] The regionalist Yorkshire Party and North East Party only hold seats at the local council level,[292] and the Northern Party, which campaigned for a devolved Northern government with the power to make laws and full control of taxation and spending, was wound up in 2016.[293][294]

Religion

Christianity

Christianity has been the largest religion in the region since the Early Middle Ages; its existence in Britain dates back to the late Roman era and the arrival of Celtic Christianity. The Holy Island of Lindisfarne played an essential role in the Christianisation of Northumbria, after Aidan from Connacht founded a monastery there as the first Bishop of Lindisfarne at the request of King Oswald.[295] It is known for the creation of the Lindisfarne Gospels and remains a place of pilgrimage.[296][297] Saint Cuthbert, a monk of Lindisfarne, was venerated from Nottinghamshire to Cumberland, and is today sometimes named the patron saint of Northern England.[298][299] The Synod of Whitby saw Northumbria break from Celtic Christianity and return to the Roman Catholic church, as calculations of Easter and tonsure rules were brought into line with those of Rome.[300]

After the English Reformation Northern England became a centre of Catholicism, and Irish immigration increased its numbers further, especially in North West cities like Liverpool and Manchester.[103] In the 18th and 19th centuries, the area underwent a religious revival that ultimately produced Primitive Methodism,[302] and at its peak in the 19th century Methodism was the dominant faith in much of Northern England.[303]

As of 2016, the list of places of worship registered for marriage for Northern England included at least 1,960 that are Methodist or Independent Methodist, 1,200 Roman Catholic, 370 United Reformed, 310 Baptist or Particular Baptist, 250 Jehovah's Witness and 240 Salvation Army, as well as many hundreds of churches from smaller denominations.[lower-alpha 13] [305]

In the ecclesiastical administration of the Church of England the entire North is covered by the Province of York, which is represented by the Archbishop of York – the second-highest figure in the Church after the Archbishop of Canterbury. The unusual situation of having two archbishops at the top of Church hierarchy suggests that Northern England was seen as a sui generis.[306] Likewise, with the exception of parts of the Diocese of Shrewsbury and Diocese of Nottingham, the North is covered in Roman Catholic Church administration by the Province of Liverpool, represented by the Archbishop of Liverpool.[307]

Other faiths

Small Jewish communities arose in Beverley, Doncaster, Grimsby, Lancaster, Newcastle, and York in the wake of the Norman Conquest but suffered massacres and pogroms, of which the largest was the York Massacre in 1190.[308] Jews were forcibly banished from England by the 1290 Edict of Expulsion until the Resettlement of the Jews in England in the seventeenth century, and the first synagogue in the North appeared in Liverpool in 1753.[309] Manchester also has a long-standing Jewish community: the now-demolished 1857 Manchester Reform Synagogue was the second Reform synagogue in the country,[310][311] and Greater Manchester has the only eruv in the United Kingdom outside London.[312] Traditionally, there is also a large Jewish presence in Gateshead. In total, there are 84 synagogues in Northern England registered for marriages.[305]

Spiritualism flourished in Northern England in the nineteenth century, in part as a backlash to the fundamentalist Primitive Methodist movement and in part driven by the influence of Owenist socialism.[313] There remain 220 Spiritualist churches registered in the North, of which 40 identify as Christian Spiritualist.[305]

The first mosque in the United Kingdom was founded by the convert Abdullah Quilliam in the Liverpool Muslim Institute in 1889.[314] Today, there are around 500 mosques in Northern England.[305][315] Indian religions are also represented: there are at least 45 gurdwaras, of which the largest is the Sikh Temple in Leeds, and 30 mandirs, of which the largest is Bradford Lakshmi Narayan Hindu Temple.[305][316][317]

Transport

Transport in the North has been shaped by the Pennines, creating strong north–south axes along each coast and an east–west axis across the moorland passes of the southern Pennines.[318] Northern England is a centre of freight transport and handles around one third of all British cargo.[319] Both passenger and freight links between Northern cities remain poor, which is a major weakness of the Northern economy.[320]

The passenger transport executive (PTE) has become a major player in the organisation of public transport within Northern city regions; of the six PTEs in England, five (Transport for Greater Manchester, Merseytravel, Travel South Yorkshire, Nexus Tyne and Wear and West Yorkshire Metro) are located in the North.[321] These coordinate bus services, local trains and light rail in their regions. Following the passage of the Cities and Local Government Devolution Act 2016, Transport for the North became a statutory body in 2018 with powers to coordinate services and offer integrated ticketing throughout the region.[320]

Road

%2C_4_February_2012_(cropped).jpg)

The Preston By-pass, opened in 1958, was the first motorway in the UK, and today an extensive network connects the major cities of the North.[323] The main western route through the North is the M6, part of a chain of motorways from London to Glasgow, while the main eastern motorway is the M1/A1(M), which runs as far north as Newcastle. The M62 links Liverpool, Manchester, Leeds and Hull across the Pennines. Other trans-Pennine roads are comparatively minor, and the lack of any dual-carriageway connection between the east and west coasts anywhere in England north of the M62 has been identified by the Department for Transport as a significant hindrance to the Northern economy.[324] In many cases, modern roads still follow ancient routes: the M62 motorway effectively duplicates the Roman road between York and Chester, while the Great North Road, the stagecoach route from London to Scotland, became the modern A1 road.[318][325]